Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Activism Strategies for Organizations

Uploaded by

IntaniaAdityaDeviayuOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Activism Strategies for Organizations

Uploaded by

IntaniaAdityaDeviayuCopyright:

Available Formats

Activism, Another initiative planners can use is activism, a confrontational strategy focused mainly on persuasive communication and the

advocacy model of public relations.

A strong strategy to be used only after careful consideration of the pros and cons, activism offers many opportunities for organizations to present their messages and enhance their relationship with key publics, particularly their members and sympathizers. Activism generally deals with causes or movements, such as social issues (crime, capital punishment or abortion, for example), environmental matters (pollution, suburban sprawl, nuclear waste), political concerns and so on. A distinction might be made between advocates, who essentially are vocal proponents for causes, and activists, who are more inclined to act out their support for the cause. Look at the discussion on opponents in Step 3 for more information about advocates and other types of social activists. Consider some of the tactics associated with the strategy of activism: strikes, pickets, sit-ins, petitions, boycotts, marches, vigils, rallies and outright civil disobedience. Activists often make effective use of the news media because their tactics involve physical protests and thus are highly visible. Effective activism often has an element of visual appeal. More than a publicity stunt, activist events involve newsworthy action done as much for the television viewers as for any other public. For example, when deathpenalty opponents marched past the Missouri governor's mansion in Jefferson City in 1999, they carried a cardboard coffin and paper tombstones. News photographers and television crews undoubtedly appreciated their visual creativity. Sometimes activism involves civil disobedience, a nonviolent and nonlegal but generally visual undertaking. Often such protests are loaded with symbolism. Julia "Butterfly" Hill set the tree-sitting record in 1999, spending 738 daysmore than two yearsatop a 1,000-year-old redwood tree in Northern California protesting a logging project. The well-publicized protest was orchestrated by Earth First!, a radical environmental activist group waging a 12-year battle to save the trees. From her residence in the tree she called "Luna," Hill gave cell-phone interviews to reporters and talked with schoolchildren around the world. This kind of activism often transforms itself into theater, particularly when protestors are courting TV coverage. Indeed the term street theater (alternatively called guerrilla theater) refers to social and political protests that take the form of dramatizations in public places. During a presidential campaign debate in October 2000 in Boston, protestors dramatized what they saw as the candidates' contempt for the masses. Dressing as bigmoney contributors with top hats and three-piece suits, they chanted mockingly: "One-two-three-four. We are rich and you are poor." And the TV video crews were delighted! The author's award for creative activist strategy goes to this well-orchestrated 1999 publicity stunt: Two dozen New York City community activists staged a sit-in on the marble floor of City Hall, singing "We Shall Overcome" accompanied by kazoos and wearing insect outfits and flowered hats. They were protesting Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's decision to auction off city-owned lots that neighborhood groups had turned ^ into community gardens. Wait, there's more: Enter the New York Police Department in ; % riot gear, and as the protestors went limp, the police had to carry them to a waiting If police van. Now that's entertainment! |$| But many protests are more serious. The Makah, a Native American tribe in Washington state, is the only whaling tribe in the lower 48 states. The tribal whaling Step commission declared its intention to return to its

traditional ways and hold a whale 5 hunt, its first in 70 years. In 1999, on live television, a successful hunt involved the ceremonial butchering of the captured whale. The media swarmed and whaling protestors gathered. Activists sometimes stretch ethical boundaries, entering an area public relations practitioners should avoid. Pie throwing has become a tactic-of-choice for some activists, who found they could gain media attention and thus a platform for their messages by pulling their relatively benign stunts on famous people. Targets have included fashion designer Oscar de la Renta, who was pied because of his use of fur; Proctor & Gamble chairman John Pepper, over animal rights; Dutch finance minister Gerrit Zalm, over the new Euro currency; Renato Ruggiero, director-general of the World Trade Organization, over endangered sea turtles; and Microsoft chairman Bill Gates, just because. In Canada, provincial pie brigades have been involved in a series of pie-throwing plots and schemes aimed at embarrassing various public officials. Usually the only consequence of pie throwing is media coverage, but three San Francisco activists who protested the mayor's policies on the homeless by throwing tofu-cream and pumpkin pies in his face were sentenced to six months in prison, and in Europe several anti-Euro protestors who used lemon meringue as their weapon of choice received short jail terms. If you are planning an activist strategy, keep a clear eye on all your publics. Certainly the news media are important. So too are the targets of your activism, whom you are attempting to persuade toward some kind of action or response. But perhaps most important is your internal publicgenerally volunteers, often with mixed motivations who are being asked to give time and perhaps take risks on behalf of the cause. Activist strategy must provide for the "feeding" of these troops with continuing motivation, ongoing communication and, when possible, the attainment of milestone victories that can shore up their dedication.

Communication Strategies

While the previous proactive strategies focus on the action of the organization, another cluster of strategies deals more with communication. Three such strategies are publicity, newsworthy information, and transparent communication.

You might also like

- Chap.9 ShepsleDocument44 pagesChap.9 ShepsleHugo MüllerNo ratings yet

- Globalisation and Social MovementDocument23 pagesGlobalisation and Social MovementSnehil NandiNo ratings yet

- Week 7: Alternative Media, Hacktivism, & Culture JammingDocument13 pagesWeek 7: Alternative Media, Hacktivism, & Culture JammingfjkgldjfNo ratings yet

- Los SIG y La Investigacion en Ciencias Humanas y SocialesDocument51 pagesLos SIG y La Investigacion en Ciencias Humanas y SocialescarlosresendizNo ratings yet

- Occupay AmericaDocument4 pagesOccupay AmericaIqbal Mahmud RanaNo ratings yet

- Rising Role Social Media ActivismDocument23 pagesRising Role Social Media ActivismTalha ImtiazNo ratings yet

- ActivismDocument5 pagesActivismVincentWijeysinghaNo ratings yet

- Chronicling Civil Resistance: The Journalists' Guide to Unraveling and Reporting Nonviolent Struggles for Rights, Freedom and JusticeFrom EverandChronicling Civil Resistance: The Journalists' Guide to Unraveling and Reporting Nonviolent Struggles for Rights, Freedom and JusticeNo ratings yet

- Global Civil Citizen: Acting As Global CitizensDocument7 pagesGlobal Civil Citizen: Acting As Global CitizensPaul Anthony Brillantes BaconNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Politics EthicsDocument14 pagesResearch Paper Politics EthicsAmila LukovicNo ratings yet

- Activist Media: Documenting Movements and Networked SolidarityFrom EverandActivist Media: Documenting Movements and Networked SolidarityNo ratings yet

- Collective Behavior, Social Movements, and Social ChangeDocument49 pagesCollective Behavior, Social Movements, and Social Changeamnahbatool785No ratings yet

- Norris-Who DemonstratesDocument18 pagesNorris-Who DemonstratesVeeNo ratings yet

- Types of Propaganda Identification GuideDocument10 pagesTypes of Propaganda Identification GuideJose FloNo ratings yet

- The Seattle ModelDocument16 pagesThe Seattle ModelJosé Manuel MejíaNo ratings yet

- Civil Disobedience - Protest, Justification and The Law - Tony Milligan PDFDocument188 pagesCivil Disobedience - Protest, Justification and The Law - Tony Milligan PDFbotab75501No ratings yet

- UC Irvine: CSD Working PapersDocument23 pagesUC Irvine: CSD Working PapersMagdalena KrzemieńNo ratings yet

- ZARET, David. Petitions and The 'Invention' of Public Opinion in English Revolution PDFDocument60 pagesZARET, David. Petitions and The 'Invention' of Public Opinion in English Revolution PDFRenato UlhoaNo ratings yet

- Concept of Associational Pressure GroupDocument10 pagesConcept of Associational Pressure GroupChinedu chibuzoNo ratings yet

- Thomas Piketty - El Capital en Siglo XXI (Español)Document4 pagesThomas Piketty - El Capital en Siglo XXI (Español)Germán LópezNo ratings yet

- Buying Power: A History of Consumer Activism in AmericaFrom EverandBuying Power: A History of Consumer Activism in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Public Opinion, Media Coverage, and Visuals Shape Environmental MovementDocument44 pagesPublic Opinion, Media Coverage, and Visuals Shape Environmental MovementMidsy De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Occupy Wall StreetDocument6 pagesOccupy Wall StreetHassan Mohammad RafiNo ratings yet

- War On Patriarchy War On The Death TechnologyDocument68 pagesWar On Patriarchy War On The Death TechnologyboukofskiNo ratings yet

- Media Manipulation - WikipediaDocument41 pagesMedia Manipulation - WikipediaArasiNo ratings yet

- Schaefer - Mass Media - Sociology PDFDocument20 pagesSchaefer - Mass Media - Sociology PDFIstana Pengetahuan SepakbolaNo ratings yet

- Occupy Wall St. - Mid Term Mass CommDocument8 pagesOccupy Wall St. - Mid Term Mass Commvishnu bhadauriaNo ratings yet

- Poster A. The Counterculture Grew Out of The Beat Movement's Emphasis On Freedom From Materialism and The Civil Rights Movement'sDocument13 pagesPoster A. The Counterculture Grew Out of The Beat Movement's Emphasis On Freedom From Materialism and The Civil Rights Movement'sapi-245498585No ratings yet

- Global Social Movement ShareDocument19 pagesGlobal Social Movement ShareSoham KumNo ratings yet

- Occupy Wall StreetDocument11 pagesOccupy Wall StreetRiya MalikNo ratings yet

- Cultural ActivismDocument249 pagesCultural ActivismMsa100% (2)

- Cancel Culture DebateDocument4 pagesCancel Culture DebateEm BakerNo ratings yet

- The Term "Collective Behaviour" Was First byDocument5 pagesThe Term "Collective Behaviour" Was First byTehr ABNo ratings yet

- Media ActivismDocument6 pagesMedia ActivismIndu GuptaNo ratings yet

- The Lumad Struggle For Social and Environmental Justice: Alternative Media in A Socio-Environmental Movement in The PhilippinesDocument16 pagesThe Lumad Struggle For Social and Environmental Justice: Alternative Media in A Socio-Environmental Movement in The PhilippinesuhhhNo ratings yet

- US - The Tactic of Occupation and The Movement of The 99%Document7 pagesUS - The Tactic of Occupation and The Movement of The 99%A.J. MacDonald, Jr.No ratings yet

- Alternative MediaDocument5 pagesAlternative MediaAnisah MohamedNo ratings yet

- Shining A Light: Admin Foundations Non-Profit Industrial Complex Whiteness & Aversive RacismDocument10 pagesShining A Light: Admin Foundations Non-Profit Industrial Complex Whiteness & Aversive RacismJay Thomas TaberNo ratings yet

- Globalization, Disobedience, and The Rule of LawDocument30 pagesGlobalization, Disobedience, and The Rule of LawRicjNo ratings yet

- Globalization and the Ideology of GlobalismDocument42 pagesGlobalization and the Ideology of GlobalismCherrie Chu SiuwanNo ratings yet

- Why Social Movements NowDocument10 pagesWhy Social Movements NowmrvfNo ratings yet

- Lumad Environmental JusticeDocument15 pagesLumad Environmental JusticeBe ChahNo ratings yet

- DirectAction PDFDocument40 pagesDirectAction PDFКрупин ДенисNo ratings yet

- The Political Power of Social Media 1Document6 pagesThe Political Power of Social Media 1HIMMZERLANDNo ratings yet

- Social Movements in American History ANSWER - EditedDocument7 pagesSocial Movements in American History ANSWER - EditedeliaswaliaulaNo ratings yet

- W. Lance Bennett - The Personalization of Politics - Political Identity, Social Media, and Changing Patterns of ParticipationDocument21 pagesW. Lance Bennett - The Personalization of Politics - Political Identity, Social Media, and Changing Patterns of ParticipationRoman SchwantzerNo ratings yet

- Process QuestionsDocument10 pagesProcess QuestionsCrash Override0% (1)

- GE6 Module 2Document10 pagesGE6 Module 2Crash OverrideNo ratings yet

- ProtestDocument6 pagesProtestapi-273347435No ratings yet

- Funding the Rise of Social MovementsDocument123 pagesFunding the Rise of Social MovementsJosé Manuel MejíaNo ratings yet

- Social MovementsDocument4 pagesSocial MovementsChinchay GuintoNo ratings yet

- The International Struggle for New Human RightsFrom EverandThe International Struggle for New Human RightsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Media Effect in SocietyDocument14 pagesMedia Effect in SocietysmskumarNo ratings yet

- Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental ImagesFrom EverandSeeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental ImagesNo ratings yet

- From Public Sphere To Public Screen: Democracy, Activism, and The "Violence" of SeattleDocument27 pagesFrom Public Sphere To Public Screen: Democracy, Activism, and The "Violence" of SeattlecayoNo ratings yet

- Whirlwinds RoadblockEFDocument7 pagesWhirlwinds RoadblockEFteamcolorsNo ratings yet

- Sociology: Social Movement From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument20 pagesSociology: Social Movement From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaHarold Palmes DimlaNo ratings yet

- GELDERLOOS Peter - The Failure of Nonviolence (2017, Left Bank Books)Document282 pagesGELDERLOOS Peter - The Failure of Nonviolence (2017, Left Bank Books)Luna Rossa100% (2)

- Tenperc PDFDocument17 pagesTenperc PDFAnthony JudgeNo ratings yet

- 14the Global Civil SocietyDocument30 pages14the Global Civil SocietyJaziel Crisostomo SestosoNo ratings yet

- Pokemon Black 2 and White 2 USA Action Replay Official Code ListDocument12 pagesPokemon Black 2 and White 2 USA Action Replay Official Code ListW A R R E N100% (1)

- Tumblr Creates Fake Scorsese FilmDocument10 pagesTumblr Creates Fake Scorsese Filmjust meNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk Case Study on Leadership and Change ManagementDocument3 pagesElon Musk Case Study on Leadership and Change ManagementPranitaNo ratings yet

- Chetna 4 EastDocument15 pagesChetna 4 EastChetana SJadigerNo ratings yet

- On MediaDocument33 pagesOn Mediaratish1533% (3)

- How To Motivate Donors To GiveDocument19 pagesHow To Motivate Donors To GiveobeidhamzaNo ratings yet

- Onyeka Abel OMOROTIONMWAN ProjectDocument51 pagesOnyeka Abel OMOROTIONMWAN ProjectFaith MoneyNo ratings yet

- Ve GeometryDocument1 pageVe Geometrymd_jamal100% (2)

- Perfume Advert AnalysisDocument4 pagesPerfume Advert AnalysisJessicaa1994No ratings yet

- Exploring The Characteristics of Millennials in Online Buying BehaviorDocument9 pagesExploring The Characteristics of Millennials in Online Buying BehaviorSha RaNo ratings yet

- 10 Steps to Motivation MasteryDocument4 pages10 Steps to Motivation MasteryBrjjdbNo ratings yet

- Kean - D&D BeyondDocument1 pageKean - D&D BeyondStupid SaiyanNo ratings yet

- Digital Marketing ProjectDocument28 pagesDigital Marketing ProjectHetik PatelNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and SponsorshipDocument6 pagesThe Impact of Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and SponsorshipOussemaNo ratings yet

- Social Media Dashboard Template: Visits Per WeekDocument5 pagesSocial Media Dashboard Template: Visits Per Weekgj1ch3240okNo ratings yet

- How To Get Free Scampage Letter For SpammingDocument63 pagesHow To Get Free Scampage Letter For SpammingMicheal Newton100% (1)

- Log Cat 1706686135444Document23 pagesLog Cat 1706686135444yonzonjohnrobert95No ratings yet

- Adg Perspective - October - November 2007 IssueDocument51 pagesAdg Perspective - October - November 2007 IssueRicardo VieiraNo ratings yet

- Kuhlau Op. 55. No. 1 PDFDocument11 pagesKuhlau Op. 55. No. 1 PDFEdward Caro NiñoNo ratings yet

- Fashion MerchandisingDocument7 pagesFashion MerchandisingSpoorthiNo ratings yet

- UI Part B 1stDocument2 pagesUI Part B 1stArun KumarNo ratings yet

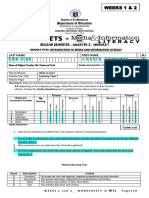

- WEEK 1-2 MIL - (Jessie Laurence N. Tomnub)Document9 pagesWEEK 1-2 MIL - (Jessie Laurence N. Tomnub)Bududut BurnikNo ratings yet

- TranslateeeDocument3 pagesTranslateeeHa NdyNo ratings yet

- Resolución - Test G2 5° Adv 3RD TermDocument3 pagesResolución - Test G2 5° Adv 3RD TermJuani Figueroa CebrianNo ratings yet

- Acute Toxic-Metabolic Encephalopathy in Adults - UpToDateDocument23 pagesAcute Toxic-Metabolic Encephalopathy in Adults - UpToDateDAFNE FRANÇA SANTANA100% (1)

- Vishal Malik NEW MEDIADocument10 pagesVishal Malik NEW MEDIAVishal MalikNo ratings yet

- Women in MediaDocument2 pagesWomen in MedialolamusgraveNo ratings yet

- Pondicherry Deduplication ListDocument1,642 pagesPondicherry Deduplication Listpawankumarsingh31No ratings yet

- Department of Computer Science and Engineering: Present VI Semester AY 2020-21 Students (R-18 Regulation)Document5 pagesDepartment of Computer Science and Engineering: Present VI Semester AY 2020-21 Students (R-18 Regulation)sarala deviNo ratings yet

- Product Spec or Info Sheet - 42080-1WSDocument2 pagesProduct Spec or Info Sheet - 42080-1WSMartin VargasNo ratings yet