Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Towards Poverty Reduction Strategy

Uploaded by

tjuttje596Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Towards Poverty Reduction Strategy

Uploaded by

tjuttje596Copyright:

Available Formats

Towards a Poverty Reduction Strategy for Indonesia

Satish Mishra, Chief Economist, UNSFIR Iyanatul Islam, ILO Expert, ILO Area Office, Jakarta

August 1, 2000

This paper was presented at the One-Day Seminar on Renewing Poverty Reduction Strategy in Indonesia, organized by BAPPENAS, on August 1, 2000, in Jakarta. The views here are the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of all UN agencies.

1. Introduction What a difference a crisis makes! It is difficult to believe that not too long ago Indonesia was hailed as an economic miracle and regarded as a rare exemplar of a country that managed to win the battle against widespread poverty. There was indeed a good deal of substance behind this rhetoric. One may well quibble over precise magnitudes and the methods underpinning measurement, but there is general agreement that both capability poverty and consumption poverty in Indonesia fell significantly on a sustained basis over the last three decades. This was the product of rapid, broad-based growth, macroeconomic stability and reasonably effective interventions in the domain of basic education and health. It is certainly a cruel irony that a country that was once won plaudits for its battle against poverty must now seek to fashion a poverty reduction strategy against a background of uncertain growth and fiscal austerity. These are, of course, the tragic legacies of the 1997 financial crisis. What started as an apparently generous rescue operation led by the international community has unfortunately not borne the expected outcome of a V-shaped recovery. The return of sustained economic prosperity that so distinguished the past remains as elusive as ever. Hence, the need to re-think the current economic strategy. It is a source of great pleasure and inspiration to see that a key agency of the government, namely BAPPENAS, is exercising leadership in thinking about future policy options where the primary goal is the emergence of a poverty-free Indonesia. It is also a matter of great privilege that we have been granted the opportunity to engage in a partnership with national stakeholders to think collectively about navigating the future in a climate of considerable challenges. To us, any strategy that will mould the destiny of the poor must ultimately be conceived, designed and executed by national stakeholders. The enduring lesson of development assistance is that donor-driven reform agendas simply do not work in the absence of a strong sense of national ownership. In essence, what we argue here is that the best way that we can contribute to the current role of BAPPENAS is to facilitate the enunciation of a poverty reduction strategy that is nationally owned and executed. What could conceivably form the elements of such a strategy?

We believe that there should to be two mutually reinforcing strands in strategy formulation. First, one should foster a professional consensus in mapping out the analytical terrain appropriate methods of monitoring poverty, identifying what work as policies and what do not, developing a clear appreciation of opportunities and threats. We believe a widely shared view on these issues is still lacking. There is both dissent and plain confusion that need to be aired. However, there is always the risk that such an exercise can become a stand-alone, technocratic affair limited to the bureaucratic elite and their peers. This is where the second strand of strategy formulation becomes so critical. The emphasis at this level ought to be on the process of consensus. This means the free and frank exchange of ideas within a framework of public consultations. Such a mechanism offers the opportunity for the government and the professional community to engage Indonesians representing diverse constituencies in the collective quest for developing a coherent vision of future policy directions. The rest of this paper attempts to articulate these themes more fully. We delineate areas in which current opinion is united and areas in which views are either insufficiently developed or even divided. We then proceed to sketch a process of public consultations that we believe is crucial in moving the poverty reduction agenda forward. 2. Identifying elements of a poverty reduction strategy in Indonesia: the need for professional consensus When the crisis started in July 1997 in Thailand and quickly spread to Indonesia, the initial concerns were with the gyrations of the exchange rate, the stock market and the need for restoring macroeconomic stability. Over the course of 1998, this gave way to grave concerns about the social consequences of the Indonesian crisis. For a while, there was a lively and robust debate on what happened to the poor as a result of the crisis. This largely methodological debate seems to have been resolved, thanks to the forthright manner in which BPS, in its capacity as a the national statistical agency, engaged with its professional peers in a range of quasi-public seminars. Such an approach quelled cynical speculations that the government was manipulating poverty statistics in a bid to

maximize the inflow of donor dollars. We now know that consumption poverty rose very sharply during the peak of the crisis, but that this tapered off as the inflation shock of 1998 abated. Despite this, current levels of consumption poverty are still significantly higher than the 1997 benchmark. Considerable uncertainty prevails over medium-term trends in poverty if slow growth and political instability persist. One of the key methodological lessons that we have learned from the aforementioned debate is that there is no single, simple approach to poverty measurement. Perhaps it is best to focus on a poverty band encapsulating alternative poverty lines rather than a unique threshold that leads to a contentious point estimate. This will render the measurement of poverty into a confidence interval within which high-case and low-case estimates will be bound. We have also learned that the monitoring of poverty requires going well beyond head count indices. They require an appreciation of the depth and severity of poverty for which appropriate indicators can be readily computed and have indeed been computed by BPS. We have learned that poverty is a multi-dimensional problem that cannot be reduced to simple numbers. It is not enough to focus on consumption poverty. It is critical to take account of developments in real wages, on nutritional standards and on a wide class of human development indicators that fall under the rubric of capability poverty. Finally, we have learned that it is necessary, particularly when an economy is subject to systemic shocks, to ensure that annual surveys on which poverty measurement is typically based ought to be supplemented by rapid-response mini-surveys that can quickly track what is happening to the poor. These lessons ought to feed into a comprehensive poverty reduction strategy, given that monitoring will be a core element of such a strategy. While we are beginning to see some clear directions emerging from the evolving debates on poverty measurement, the same cannot be said of a host of other issues. We will elucidate this proposition by focusing: on the role of social protection in poverty alleviation on the link between decentralization and poverty on the fiscal squeeze and its impact on the governments commitment to social expenditures, such as health and education.

Social protection and poverty In recent discourse, we have detected the troubling tendency both within the government and elsewhere - to make a distinction between social safety net (SSN) mechanisms and mainstream poverty reduction initiatives. We believe that this dichotomy is debatable and hence needs to be debated. The prevailing perception seems to be that SSN programmes were emergency-type responses to the crisis and should be phased out and replaced by mainstream poverty reduction initiatives. Several kinds of argument underpin this position. First, there is the populist view that waste and malfeasance riddled SSN programmes. Second, there is the notion that it is ultimately the resilience of individual households and the network of friends and family that enabled the poor to cope with the crisis. In the presence of such a well-functioning informal system of social protection, formal social protection systems are irrelevant and may well end up supplanting efficient, community-based initiatives. Third, it is noted that, given Indonesias current state of development and predicament, a comprehensive system of social protection is fiscally unaffordable and by using up scarce resources, it will probably act as a drag on growth. None of these arguments find support from either theory or evidence. Notable economists, such as the Noble Laureate Amartya Sen and Dani Rodrik of Harvard University, have argued that social protection measures are the hallmarks of any humane and democratic society. Furthermore, the relevance of such measures has intensified because the relentless process of globalization has actually increased the vulnerability of national polities to systemic economic shocks. Based on carefully calibrated case studies, some economists have argued that so-called informal systems of social safety nets are actually inefficient and cannot simply cope with large-scale crises. Others have assembled cross-country econometric evidence to conclude that expenditures on social protection promote growth because they can alleviate social conflicts (typified by riots, rebellion, criminal activity etc). The allegation that SSN programmes were afflicted by waste and malfeasance ignores growing evidence that several components such as the OPK programme and the scholarship programme worked reasonably well. Of course, they were by no means perfectly targeted, but neither were they utterly wasteful and useless. Our own view is that, in the absence of the

SSN programmes, an additional 7-12 per cent of Indonesian households would have fallen below the poverty line. As far as the issue of fiscal affordability is concerned, the available evidence once again does not support the critics. A recent WFP report has highlighted that, despite the apparently vast sums (approximately Rp 5 trillion in 1999), the SSN programmes only amount to 0.5 per cent of GDP. Such a statistic pales into insignificance when one considers the various fiscal commitments of the government that do not have a direct bearing on poverty. For example, the petroleum and electricity subsidies are going to absorb 2.2 per cent of GDP in 2000 (Rp 25 trillion that is five times the value of the SSN programme), although it is widely believed that such subsidies generally benefit upper and middle-income groups. These issues are re-visited at a subsequent juncture. Studies by the ILO have shown that even if the government adopts formal social protection measures as a durable element of a comprehensive poverty programme, they are unlikely to be fiscally taxing. Consider, for example, the specific case of unemployment benefits which is, of course, the most widespread form of social protection in industrial countries. The ILO has shown that it would have taken an average required contribution of only 0.4 of payroll from 1991-2000 for the Indonesian government to provide all insured job losers over this period, including during the current crisis, with 12 months of benefits. In sum, the role of social protection in any poverty reduction strategy for Indonesia should be re-considered. At the very least, an open debate on this issue is necessary. Decentralization and poverty The general perception is that decentralized governance will bring about more effective poverty alleviation programmes by bringing the government closer to the people and by creating a conducive environment for more efficient public service delivery mechanisms. Unfortunately, recent evaluations on the link between decentralization and anti-poverty policies in developing countries suggest a rather ambivalent picture. Often, the local decisionmaking machinery becomes prone to capture by elites in the absence of a well-functioning legislature, a robust civil society and a free press. Furthermore, whether by design or default, central governments tend to display re-centralizing tendencies. Case studies of

decentralization highlight examples of countries that undertook them too fast and on too wide a scale without any clear strategic intent, and usually in a turbulent context of political and economic crises. The current decentralization agenda in Indonesia displays characteristics that are uncomfortably close to the cases of failure documented in recent evaluations. It is proceeding in the context of ethnic conflicts and political uncertainty stemming from the secessionist tendencies of resource-rich provinces. It is occurring in the wake of a deep economic recession and dwindling fiscal resources. It is moving ahead without a clear vision of how decentralization will support the governments core mission of eliminating poverty. In our own work, where we managed to engage in consultations with more than 300 stakeholders representing diverse regional communities spread across 10 provinces, we came across the disturbing mind-set of decentralize now, deal with the problems later. We interpret this as a manifestation of the paradox of regional discontent. Three decades of overly centralized and authoritarian rule has bred a sense of innate distrust of the central government among regional communities. Thus, despite grave misgivings about the design of the overall decentralization framework, representatives of regional communities that we spoke to are impatient to move ahead, fearing that any delay will be used an excuse by the central government to stall forever. We also feel that the politicization of the current decentralization agenda bears the strong imprint of the particular interests of a few resourcerich provinces. Despite such concerns, we maintain that decentralization in Indonesia is long overdue and, in any case, is an irreversible process. Properly designed and executed, decentralization can indeed be a potent instrument for maintaining both national cohesion and furthering the core objective of reducing poverty. The trouble is that this linkage between instrument and goals has not been clearly articulated in the current decentralization framework. We have in the past argued the case for crafting a social accord where the core mission of decentralization is the elimination of the worst forms of regional disparities. This would entail the enunciation of minimal national standards of human development that all regional communities will be entitled to. Note that such an approach does not encroach on the opportunity for the more dynamic regions to forge ahead. By mandating minimal human

development standards across regions, a social accord on decentralization may well promote national cohesion and reduce poverty at the regional level. The fiscal squeeze and the governments commitment to pro-poor policies After being extolled for decades for its virtuous record of fiscal prudence, Indonesia now finds itself in the midst of dwindling fiscal resources. This, of course, is the harsh legacy of the 1997 financial crisis. A considerable slice of public resources (36 per cent of domestic revenue and 27 per cent of the total budget) is being consumed in servicing the governments domestic and external debt. The latter, in turn, is a direct consequence of the governments attempt to recapitalize a moribund banking system and the assumption of large-scale private debt. Indonesia has ended up with the unenviable position of trying to deal with one of the costliest bank restructuring programmes, currently amounting to well over 50 per cent of GDP. What strikes us as rather odd is the lack of a robust public debate and hence open acknowledgement - of the opportunity cost of tying up scarce fiscal resources in an enterprise that has so far failed to yield tangible and widespread benefits, despite claims that it is the central plank of the current reform strategy. The key issue, when analyzing the opportunity cost of current and projected budgetary allocations, is the extent to which such allocations will impede the government in its mission to build a credible poverty reduction strategy. There is no commonly agreed position on the issue of the costs and benefits that flow from the prevailing practice of fiscal management. One could start by arguing that there is no alternative (a case of TINA). The government has to diligently pursue the current course of action. The opportunity cost of not doing so is a fatally impaired financial system, a longterm cessation of the inflow of foreign capital caused by a lack of investor confidence and hence the persistence of economic stagnation. This in turn will lead to long-term increases in poverty, however creative the government is with attempts to protect the poor from the predictable consequences of economic stagnation. The TINA proposition would thus maintain that diligently pursuing the bank-restructuring programme is ultimately pro-poor in orientation, despite the seemingly vast sums that are being expended to sustain this strategy. Supplementing this proposition is the argument that

the primary focus in fiscal management as it pertains to funding poverty reduction programmes should be the optimization of efficiency in the delivery of social services, enabling the government to achieve its goals even in an era of dwindling public resources. We are not as sanguine as the advocates of the TINA proposition. We believe that an open, but informed, public debate should occur on the implications of current and projected budgetary allocations. After all, embedded in fiscal management are implicit value judgements and unstated political priorities. When, for example, the government fails to put a cap on the escalating costs of recapitalizing the banking system, or when it decides to persist with the subsidization of petroleum and electricity that is five times as costly as a social safety net programme, it is conveying a signal that it cares more about certain groups and sectors in society than others. The virtue of an open public debate is that it enables stakeholders to consider these value judgements and political priorities in a transparent and accountable manner. We also believe that the emphasis on efficiency in the use of public resources at a time when the fiscal envelope is tightly circumscribed creates a sense of false optimism on what is achievable. If there are minimal amounts that are required to fund anti-poverty programmes, and if current and projected resources fall short of such minimal standards, then exhorting the government to do more with less is to ask a starving person to be parsimonious with his diet. To illustrate this point, consider the following numbers. A casual glance at the available statistics shows that it would cost the government around 2.3 per cent of GDP to bring everybody above the poverty line. This translates to roughly Rp 26 trillion at current prices. Will the government be able to maintain this threshold in real terms over the medium term? Unless such a basic question is resolved, a poverty reduction strategy runs the risk of being empty rhetoric. Our fear is that the governments commitment to social expenditure is under serious pressure. For the year 2001, for example, development expenditure on education and health is likely to decline by 26 per cent and 39 per cent in real terms relative to this year. It is difficult to believe that such steep (projected) declines represent the culling of spare fat from the system. In sum, a clear appreciation of the implications of current and projected budgetary expenditure must be at the core of any discussion of a poverty reduction strategy for

Indonesia. There are competing interpretations on what these implications are. The reconciliation of these interpretations within the context of informed public discourse is of paramount importance. 3. Moving ahead with a poverty reduction strategy: getting the process right As noted, identifying the core issues in an anti-poverty strategy and reaching a professional consensus on these issues is only one plank of strategy formulation. How the consensus itself is forged is critical. Let us re-state our proposition: we believe that consensus building ought to occur within the framework of widespread public consultations. This process is fundamental to ensuring that policy debates do not become closed-door sessions run by technocrats. The goal of inculcating national ownership of any reform strategy in turn becomes more feasible. We suggest a possible process that could take a putative poverty reduction strategy forward. Thus: 1. 2. The government starts with a Presidential Commission on poverty alleviation. The Commission launches quasi-public hearings from experts that trigger publicizing of existing and forthcoming professional evaluations on the prevailing portfolio of poverty programmes and draws in international experiences. This is combined with regional consultations of all pertinent stakeholders. 3. A technical secretariat within the Commission integrates the findings in a series of White Papers (e.g. on social protection, on pro-poor fiscal management, on the linkage between decentralization and poverty etc) that are formally launched within the context of a national convention. 4. The White Papers could include variants of a poverty reduction strategy (say, twoto-three versions) with a recommended option. The variants should contain enough implementation detail vis--vis functions of different levels of government, financing mechanisms, accountability mechanisms etc. 5. 6. The White Papers, together with the deliberations of the convention, are conveyed to Parliament. Assuming all above steps run smoothly, a poverty reduction strategy is set over the five-year planning period.

Donors can assist this process in a number of ways. Thus: They can facilitate the work of the Presidential Commission and its technical secretariat and engage in a division of labour on the professional evaluations, reflecting preferences and comparative advantage of different agencies They can facilitate the production of the White Papers They can facilitate the regional consultations They can facilitate the holding of the national convention We hope that the process that we have sketched is worthy of consideration by the BAPPENAS and pertinent stakeholders. We stand ready to assist and support the government in building national ownership of a holistic development strategy.

You might also like

- Ending Poverty: How People, Businesses, Communities and Nations can Create Wealth from Ground - UpwardsFrom EverandEnding Poverty: How People, Businesses, Communities and Nations can Create Wealth from Ground - UpwardsNo ratings yet

- Time To Change Strategic Thinking: Local / Global EncountersDocument3 pagesTime To Change Strategic Thinking: Local / Global EncountersLuis J. González OquendoNo ratings yet

- India Chronic Poverty ReportDocument208 pagesIndia Chronic Poverty ReportRamana Akula100% (1)

- Evolution of PovertyDocument41 pagesEvolution of PovertyShoaib Shaikh100% (1)

- Poverty Dissertation ProposalDocument8 pagesPoverty Dissertation ProposalDltkCustomWritingPaperUK100% (1)

- Social Cash TransfersDocument6 pagesSocial Cash TransfersAliya TokpayevaNo ratings yet

- Measurement of Poverty and Poverty of Measurement: Martin GreeleyDocument15 pagesMeasurement of Poverty and Poverty of Measurement: Martin GreeleyKule89No ratings yet

- Social Protection and Social Development: The Recent Experience in BrazilDocument18 pagesSocial Protection and Social Development: The Recent Experience in BrazilUNDP World Centre for Sustainable DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Globalization and SustainabilityDocument13 pagesGlobalization and SustainabilityCarl Jason GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Defining and Measuring Inclusive Growth: Application To The PhilippinesDocument45 pagesDefining and Measuring Inclusive Growth: Application To The PhilippinesAsian Development Bank100% (1)

- PRESENTACIÓNDocument3 pagesPRESENTACIÓNhbjbbhjbbNo ratings yet

- Dev Econ FinalDocument8 pagesDev Econ FinalPrincess Joy ManiboNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Tourism: Basic Income For Poor CommunitiesDocument27 pagesSustainable Tourism: Basic Income For Poor CommunitiesZoran H. VukchichNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four Poverty Alleviation: Imperical StudiesDocument31 pagesChapter Four Poverty Alleviation: Imperical Studiesgosaye desalegnNo ratings yet

- There Are Four Reasons To Measure Poverty:: One ApproachDocument6 pagesThere Are Four Reasons To Measure Poverty:: One ApproachHilda Roseline TheresiaNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Thinking About Poverty: Phase I: Income and Expenditure Based ThinkingDocument9 pagesEvolution of Thinking About Poverty: Phase I: Income and Expenditure Based ThinkingShoaib ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Who Gets What? The Political Economy of RedistributionDocument2 pagesWho Gets What? The Political Economy of RedistributionSTEPHEN NEIL CASTAÑONo ratings yet

- Absolute Poverty Physical Well-Being Consumption Goods Poverty Line IncomeDocument2 pagesAbsolute Poverty Physical Well-Being Consumption Goods Poverty Line IncomeShawie AbingNo ratings yet

- Daftar Judul JurnalDocument20 pagesDaftar Judul JurnalBudi Gatot MNo ratings yet

- Essay Care Social FamDocument7 pagesEssay Care Social FamDorian MauriesNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument19 pagesUntitledcarapalida01No ratings yet

- Approach To Poverty Reduction in Developing Countries and Japan's ContributionDocument5 pagesApproach To Poverty Reduction in Developing Countries and Japan's ContributionDaljit SinghNo ratings yet

- Dev. Economics HW2 - 2206065045 - Vetry Yoel HalomoanDocument8 pagesDev. Economics HW2 - 2206065045 - Vetry Yoel Halomoanvetryyoel12No ratings yet

- Barrientos and Nino-Zarazua (2011) Social Transfers and Chronic Poverty. Objectives, Design, Reach and ImpactDocument44 pagesBarrientos and Nino-Zarazua (2011) Social Transfers and Chronic Poverty. Objectives, Design, Reach and ImpactMiguel Nino-ZarazuaNo ratings yet

- Economic Adjustment and Targeted Social Spending: The Role of Political Institutions (Indonesia, Mexico, and Ghana)Document43 pagesEconomic Adjustment and Targeted Social Spending: The Role of Political Institutions (Indonesia, Mexico, and Ghana)Michel Monkam MboueNo ratings yet

- Some Principles For Unity and Human DevelopmentDocument12 pagesSome Principles For Unity and Human DevelopmentPro GuyanaNo ratings yet

- Activity 5Document4 pagesActivity 5Polpol DiamononNo ratings yet

- Aquino - Comprehensive ExamDocument12 pagesAquino - Comprehensive ExamMa Antonetta Pilar SetiasNo ratings yet

- AE 210 - Assignment # 2Document3 pagesAE 210 - Assignment # 2Jinuel PodiotanNo ratings yet

- Understanding Poverty and Wellbeing: A Note With Implications For Research and PolicyDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Poverty and Wellbeing: A Note With Implications For Research and Policycomentarioz7691No ratings yet

- Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction in Nigeria An Empirical InvestigationDocument14 pagesEconomic Growth and Poverty Reduction in Nigeria An Empirical InvestigationAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Final Halving Global PovertyDocument31 pagesFinal Halving Global PovertyFiras FrangiehNo ratings yet

- Discuss The Role of Inclusive Economic Development in Eradicating PovertyDocument5 pagesDiscuss The Role of Inclusive Economic Development in Eradicating PovertyWasifa Tahsin AraniNo ratings yet

- Sustaining Poverty Escapes In: NigerDocument20 pagesSustaining Poverty Escapes In: NigerJesus AntonioNo ratings yet

- IPCWorkingPaper60 - From Social Safety Net To Social Policy? The Role of Conditional Cash Transfers in Welfare State Development in Latin AmericaDocument35 pagesIPCWorkingPaper60 - From Social Safety Net To Social Policy? The Role of Conditional Cash Transfers in Welfare State Development in Latin AmericaEmma 'Emmachi' AsombaNo ratings yet

- Global Inequality and The FutureDocument4 pagesGlobal Inequality and The Futuredwayne.joed21No ratings yet

- Understanding Global Poverty Summary Chap#2Document5 pagesUnderstanding Global Poverty Summary Chap#2Hajra Aslam AfridiNo ratings yet

- Universal Basic IncomeDocument31 pagesUniversal Basic IncomeumairahmedbaigNo ratings yet

- Discussion For Chap. 4Document2 pagesDiscussion For Chap. 4Juvilyn PaccaranganNo ratings yet

- Financial Awareness in Everyday Life Due To The Pandemic, Based On The Results of A Hungarian Questionnaire SurveyDocument13 pagesFinancial Awareness in Everyday Life Due To The Pandemic, Based On The Results of A Hungarian Questionnaire SurveyGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Drugs and Poverty Literature ReviewDocument14 pagesDrugs and Poverty Literature Reviewc5nazs86100% (1)

- Working Paper Number 107 Does It Matter That We Don't Agree On The Definition of Poverty? A Comparison of Four ApproachesDocument41 pagesWorking Paper Number 107 Does It Matter That We Don't Agree On The Definition of Poverty? A Comparison of Four ApproachesJase HarrisonNo ratings yet

- Population Control Policy of PakistanDocument26 pagesPopulation Control Policy of PakistanAbid Hussain0% (1)

- RCT Abhijeet BaneerjeeDocument6 pagesRCT Abhijeet BaneerjeeSyed Zaffar NiazNo ratings yet

- Article On Effects of Public ExpenditureDocument11 pagesArticle On Effects of Public Expendituretanmoydebnath474No ratings yet

- An Exploratory Study On Communication and PovertyDocument9 pagesAn Exploratory Study On Communication and PovertyBrian BasseyNo ratings yet

- Block 1 MEC 008 Unit 2Document12 pagesBlock 1 MEC 008 Unit 2Adarsh Kumar GuptaNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- No-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesNo-One Written Off: Reforming Welfare To Reward ResponsibilityOxfamNo ratings yet

- Forms of Capital by Bourdieu (1986)Document7 pagesForms of Capital by Bourdieu (1986)Kalimah Priforce100% (1)

- Bis. Research MethodsDocument136 pagesBis. Research Methodsnebiloo1No ratings yet

- Education and Poverty: A Gender Analysis: by Zoë OxaalDocument26 pagesEducation and Poverty: A Gender Analysis: by Zoë OxaalSmithy SimilikitiNo ratings yet

- Building A Global Citizen in ThailandDocument17 pagesBuilding A Global Citizen in Thailandtjuttje596No ratings yet

- Comp1 Adapting To Climate Change in Urban AreasDocument124 pagesComp1 Adapting To Climate Change in Urban Areastjuttje596No ratings yet

- Financial Assets, Money, Financial Transactions, and Financial InstitutionsDocument24 pagesFinancial Assets, Money, Financial Transactions, and Financial InstitutionsJeremy MacalaladNo ratings yet

- Time Sheet Bulanan Periode April 2023Document13 pagesTime Sheet Bulanan Periode April 2023Suto WijoyoNo ratings yet

- GGGDocument4 pagesGGGTaha Wael QandeelNo ratings yet

- Alphaex Capital Candlestick Pattern Cheat Sheet InfographDocument1 pageAlphaex Capital Candlestick Pattern Cheat Sheet InfographAdnankNo ratings yet

- CÂU HỎI TRẮC NGHIỆM XÁC ĐỊNH TỶ GIÁ HỐI ĐOÁI 1Document3 pagesCÂU HỎI TRẮC NGHIỆM XÁC ĐỊNH TỶ GIÁ HỐI ĐOÁI 1Nhi PhanNo ratings yet

- Unit Test 6 PDFDocument2 pagesUnit Test 6 PDFSacma SapanNo ratings yet

- EN ISO 5398-2 (2009) (E) CodifiedDocument3 pagesEN ISO 5398-2 (2009) (E) CodifiedsamiNo ratings yet

- Gregory Feb 2020 Wells StatementDocument4 pagesGregory Feb 2020 Wells StatementYoooNo ratings yet

- A Cebuana Lhuillier Branch in Angeles CityDocument2 pagesA Cebuana Lhuillier Branch in Angeles CityitsmenatoyNo ratings yet

- Yosef AddisuDocument94 pagesYosef AddisuBirukNo ratings yet

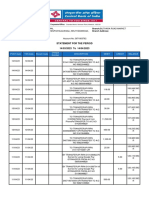

- Statement For The Period 14/03/2023 To 14/04/2023Document6 pagesStatement For The Period 14/03/2023 To 14/04/2023Adrian LamoNo ratings yet

- PERCENTAGE CLASS-3 (By Ashish Rathi Sir)Document3 pagesPERCENTAGE CLASS-3 (By Ashish Rathi Sir)rjNo ratings yet

- I Love My Planet - BookDocument14 pagesI Love My Planet - BookmarianafartadoNo ratings yet

- The RSI Pro The Core PrinciplesDocument34 pagesThe RSI Pro The Core PrinciplesThang NguyenNo ratings yet

- FBN Eligible ItemsDocument351 pagesFBN Eligible Itemsعجلة الاكسسواراتNo ratings yet

- Klaim Grogot 18-22 April 22Document10 pagesKlaim Grogot 18-22 April 22Bos GenkNo ratings yet

- Transactions List: Cristina Borlan RO19BRDE250SV39314472500 RON Cristina BorlanDocument5 pagesTransactions List: Cristina Borlan RO19BRDE250SV39314472500 RON Cristina BorlanCrNo ratings yet

- Notes ReceivableDocument17 pagesNotes ReceivableMichael JimNo ratings yet

- SPK Presentation 2021Document24 pagesSPK Presentation 2021Mohamed RazickNo ratings yet

- EcoMatrix KKDocument5 pagesEcoMatrix KKKunal KumarNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 8 9 and 10 1Document42 pagesChapter - 8 9 and 10 1aaxdhpNo ratings yet

- Ged105 Quiz 1 TCWDocument21 pagesGed105 Quiz 1 TCWasdasdasdasdasdNo ratings yet

- 06 Calculating NPV ShellDocument1 page06 Calculating NPV ShellSyed TabrezNo ratings yet

- Philippine-Clearing-House-Corporation ReportDocument32 pagesPhilippine-Clearing-House-Corporation ReportJohn Carlo BuayNo ratings yet

- Due To Use of Advanced Technology The Use of Labor Reduce Significantly. Because of That The Unskilled Employees Lost Their JobsDocument3 pagesDue To Use of Advanced Technology The Use of Labor Reduce Significantly. Because of That The Unskilled Employees Lost Their JobsAhron CulanagNo ratings yet

- 19bbl110 FINAL RESEARCH PAPERDocument20 pages19bbl110 FINAL RESEARCH PAPERShubham TejasNo ratings yet

- UTS Audit II-1Document3 pagesUTS Audit II-1NafisNo ratings yet

- V3 Trading HistoryDocument10 pagesV3 Trading Historyjoxihol941No ratings yet

- Gratitude in ActionDocument19 pagesGratitude in Actionrg DelacernaNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 PaperDocument3 pagesCOVID-19 PaperJacob SheridanNo ratings yet