Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Intellectual Property Magazine - Charles Colman Louis Vuitton Penn Law School Article 'Lessons in Trademark Enforcement - Bullion Without Bullying'

Uploaded by

Charles E. ColmanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Intellectual Property Magazine - Charles Colman Louis Vuitton Penn Law School Article 'Lessons in Trademark Enforcement - Bullion Without Bullying'

Uploaded by

Charles E. ColmanCopyright:

Focus on brands online

Lessons in trademark enforcement: bullion without bullying

Charles Colman Laws Charles E Colman looks at how an aggressive trademark strategy can work against you

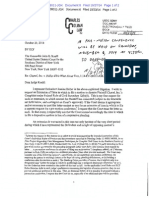

Louis Vuitton Malletier, SA (Louis Vuitton), is proud of its trademarks, and it is not afraid to show it. The fashion heavyweight has repeatedly made headlines over the past six months for its aggressive efforts to police the use of its trademarks. Such efforts include taking on not only run-of-themill counterfeiters (and winning)1, but also declaring war on such daunting foes as Warner Brothers2 (for the alleged misrepresentation of an imitation Vuitton bag as the real thing in The Hangover: Part II). At issue in most of these disputes is Louis Vuittons registered Toile Monogram trademark, a repeating pattern design of the letters LV and ower-like symbols on a chestnut background. Perhaps inspired by Louis Vuittons highly publicised trademark enforcement tactics, a student at the University of Pennsylvania Law School came up with a clever graphic design concept earlier this year. In order to promote the student-run Penn Intellectual Property Groups 2012 annual symposium on Fashion Law, the group released a poster and invitation whose top third consisted of a modied Toile Monogram pattern. Given the nature of the conference, Louis Vuittons interlocking LV had been substituted with an interlocking TM for trademark, while some ower icons now appeared as the copyright symbol. The mischievous result can be seen below: several large law rms. As Louis Vuitton had not sponsored the event, its name did not appear in this portion of the poster though it soon became involved in an altogether different capacity. Vuitton Malletier SA v Haute Diggity Dog, LLC, 507 F3d 252 (4th Cir 2007)3. Firestones infringement argument was respectable, if more vulnerable than his dilution defence. He asserted that the legal professionals attending the conference certainly are unlikely to think that Louis Vuitton is organising the conference, given the posters indication that PIPG has organised the event, with support from Penn Law and a number of nationally-known law rms. Further, no reasonable person would be confused about Louis Vuittons (lack of) involvement with the symposium merely because of the clever artwork parody. Perhaps most powerfully, Firestone pointed out that the artwork was designed to evoke some of the very issues to be discussed at the conference, which he then enumerated. In closing, Firestone encouraged Pantalony to attend the conference (though it seems he was a no-show.) Like Pantalonys letter, Firestones email ew around the internet. The dispute apparently concluded with Firestones response, as the poster was not retracted and the event took place as scheduled.

Only Pantalony

On 29 February 2012, Penn Law Dean Michael A Fitts received an email from one Michael Pantalony, Louis Vuittons Director of Civil Enforcement for North America. Pantalony wrote to express [his] concerns over the unauthorised use of [the companys trademarks to promote the 20 March symposium. In Pantalonys view, the student group behind the event (PIPG) had misappropriated and modied the LV trademarks and Toile Monogram, which Pantalony considered an egregious action [of] serious willful infringement [that] knowingly dilute[d] the LV trademarks. The harm, according to Pantalony, lay in the risk that the poster might mislead viewers into believing that the PIPGs modication of the Toile Monogram constituted legal fair use and/or inaccurately suggest that Louis Vuitton either sponsored the seminar or was otherwise involved. Pantalony lamented that he would have thought the Penn Intellectual Property Group would understand the basics of intellectual property law and know better than to infringe and dilute the famous trademarks of fashion brands. The letter quickly made its way onto the internet, where it was widely circulated.

Who was right?

Firestones invitation to Pantalony could be read as disingenuous, but his list of the issues to be addressed at the symposium was downright diplomatic. Firestone graciously declined to mention, for example, that an effective evaluation of a proposal (like the IDPPPA, the subject of its own panel) to create new IP rights requires a probing examination of how existing rights have been used (or abused) by the proposed laws beneciaries. Firestone could have pointed out (but did not) that by making its threat, Louis Vuitton had virtually guaranteed that trademark bullying by IP owners and probably, by Louis Vuitton in particular would now be on the conference agenda. (Indeed, the topic was discussed at the event.) In other words, Louis Vuittons aggressive response to the poster actually reduced the likelihood that trademark infringement or dilution had occurred by increasing the topicality and freespeech implications of the parody. To be fair, not all of Firestones punches landed. He missed the mark in expressing his

Penn Fires(tones) back

On 2 March 2012, the universitys associate general counsel, Robert F Firestone, lobbed his own missive back at Pantalony. Firestone wisely led with his strongest point: the poster could not dilute any of Louis Vuittons marks because a provision of the federal Lanham Act, 15 USC 1125(c)(3), in Firestones words, expressly protects a noncommercial use of a mark and a parody from any claim for dilution. In Firestones view, the issue was simple: A law student group at a non-prot university promoting its annual educational symposium is a noncommercial use. As if to rub salt in the wound, Firestone then cited one of Louis Vuittons greatest defeats: Louis

The poster for the 20 March 2012 symposium advertised two panels: Trademark and the Fast Fashion Phenomenon and Copyright for Fashion Design: Evaluating the Innovation Design Protection and Piracy Prevention Act (IDPPPA), along with a keynote address. The poster maintained the same brown-and-gold colour scheme throughout, with the exception of a section for sponsors, featuring the imported logos of Penn Law and

www.intellectualpropertymagazine.com

May 2012

Intellectual Property magazine 41

doubt[s that] any of [LVs] trademarks are registered in Class 41 to cover educational symposia in intellectual property law issues. The proximity of the products [or services at issue] is, of course, just one of many likelihood of confusion (or Polaroid) factors used to adjudicate claims of trademark infringement. Further, the specic classes listed in a trademark registration are not dispositive on this issue. Conversely, Pantalonys assertion that Louis Vuitton had sponsored [educational] activities in the past proves too much. Indeed, the same test for likelihood of confusion Polaroid factor mentioned above is concerned not only with the proximity of the plaintiffs and defendants goods or services, but with their competitive proximity4. If, as the Second Circuit has stated, vodka rum, and malt beveragesreside in distinct submarkets for purposes of competitive proximity5, it is silly to make much of Louis Vuittons occasional dabbling in educational programmes. Most large corporations, of course, have backed events outside of their primary industries; that is neither here nor there. True, there is the Lanham Acts sponsorship/afliation language to consider6. But it is probably safe to say that there is no signicant public recognition of Louis Vuitton as a commercial provider or as a consistent sponsor of educational goods or services. Further, as a normative matter, do we really want to stretch the sponsorship, afliation, connection, or identication7 language of the Lanham Act so far as to include every non-critical, referential use of anothers trademark? Even Louis Vuitton stopped short of taking such an extreme position in the Warner Brothers case, urging the District Court to impose liability for the Hangover IIs alleged misrepresentation of an imitation bag as the real thing not merely for the unauthorised use of a genuine Louis Vuitton bag.

The bottom line

Perhaps because the Penn Law poster showdown had a certain ivory tower air about it, it likely caused little lasting damage to the Louis Vuitton brand. But that does not mean companies should follow Louis Vuittons example, as things can go far worse for aggressive IP owners who overstep in the digital age. Consider another fashion-related PR debacle, which arose in mid-2011, when inhouse counsel for retail chain Forever 21 sent a cease-and-desist letter to blogger, Rachel Kane, over alleged trademark infringement and dilution (and copyright infringement) on her site, WTForever21.com10. Kane, a social media-savvy twenty-something, promptly posted and circulated the letter. Unlike the Louis Vuitton-Penn Law dispute, the WTForever 21 story made headlines in virtually every national media outlet. It is, of course, impossible to know how many consumers read about Kanes case and changed their purchasing habits as a result. Further, there is at least reason to believe that Forever 21 feared a PR backlash: shortly after Kane instructed a lawyer and Forever 21 backed down, the company anointed a blogger the new face of the company. Naturally, some expressed skepticism about Forever 21s motives11.

Let them eat cake (sometimes)

By this point, it should be obvious that companies must tread carefully when handling situations like the Penn Law School poster or the WTForever 21 blog. Corporate counsel should keep in mind that cease-anddesist letters can and often will be posted and circulated on the internet, resulting in much greater exposure for the allegedly infringing material. Further, consumers frequently confuse cease-and-desist letters with lawsuits12, exacerbating the PR fallout. And the smaller the target, the greater the likely damage, as the public will readily side with an individual targeted by a large corporation. In short, while it is certainly important to police ones trademark, not every debatable use of a mark need be squelched; indeed, diverting resources toward parodies particularly where doing so will only increase their exposure will often then prove to be a waste of valuable company time, or worse. With the public increasingly attuned to the issue of trademark bullying, companies should (re)prioritise their targets and evaluate the real risk of letting marginal infringers have their fun. To paraphrase the wife of another Louis, sometimes, it is best to simply let them eat cake.

The People v Louis Vuitton

The journalistic and popular response to Louis Vuittons letter, while not as vociferous as the outcry following similar threats in the past, was by no means trivial. Foley Hoag LLPs trademark & copyright law blog noted that Pantalony had set the blogosphere atwitter by sending [his] sternly-worded cease-and-desist letter and speculated that the threat had likely proved to be a far more successful publicity tool than [the posters] designers could have originally hoped8. Reuters Alison Frankel was more openly critical, asking, Is there any trademark owner with less of a sense of humour than Louis Vuitton9?.

Footnotes 1. See, eg, Louis Vuitton Malletier SA v LY USA, Inc, 08-4483-CV, 2012 US App LEXIS 6391, at *76-*77 (2d Cir 29 March 2012); In the Matter of Certain Handbags, Luggage, Accessories and Packaging Thereof, ITC Inv No 337-TA-754 (US Intl Trade Commn Order No. 16, 5 March 2012). 2. Louis Vuitton Malletier, SA v Warner Bros Ent Inc, 11 Civ 9436 (SDNY 22 December 2011) (Complaint led; case status pending). 3. Firestone did not quote any passages from the Fourth Circuits opinion in what has come to be known as the Chewy Vuitton dog toy case. Notably, the court had found for the defendant in that case in part because it had used CV to mimic LV adopt[ing] imperfectly the items of LVMs designs. id at 268 (emphasis in original). PIPGs transformation of LV into TM is strikingly similar. 4. Star Indus v Bacardi & Co, 412 F3d 373, 386 (2d Cir 2005) (emphasis added). 5. Star Indus v Bacardi & Co, 412 F3d 373, 387 (2d Cir 2005). 6. See 15 USC 1125(a)(1)(A). 7. id at 383. 8. Jenevieve Maerker, Trademark parody dispute puts fashion law in the spotlight, 21 March 2012, at http://bit.ly/GIIbPa. 9. Alison Frankel, Louis Vuitton and Penn offer unintended lesson in trademark law, Thomson Reuters News & Insight, 9 March 2012, at http:// reut.rs/xwr2Fz. 10. In the interest of full disclosure, my rm, Charles Colman Law, PLLC, served as Kanes co-counsel, alongside the Los Angeles-based Doniger/ Burroughs Law Firm. 11. Lovelyish.com, The new face of Forever 21 is a blogger: how ironic, 8 July 2011, at http://bit.ly/ Hv4XFk. 12. See, eg, Jenna Sauers, Forever 21 sues fashion blogger, Jezebel, 6 June 2011, at http://bit.ly/ is0Y22 ([t]his seems like a textbook example of a SLAPP, a lawsuit or legal threat that is intended not to win a claim, but to silence a critic.)

Author

Charles E Colman is the founder of Charles Colman Law, PLLC, where he handles intellectual property disputes and other legal matters arising in fashion, music, and art.

42 Intellectual Property magazine

May 2012

www.intellectualpropertymagazine.com

You might also like

- Submission To The US Trade Representative Special 301 Review, 2011Document5 pagesSubmission To The US Trade Representative Special 301 Review, 2011Andrew NortonNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3306431Document16 pagesSSRN Id3306431Astrid KumalaNo ratings yet

- The Motley Fool You Have More Than You Think: The Foolish Guide to Personal FinanceFrom EverandThe Motley Fool You Have More Than You Think: The Foolish Guide to Personal FinanceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Certificat de Compétences en Langues de L'Enseignement Supérieur ClesDocument5 pagesCertificat de Compétences en Langues de L'Enseignement Supérieur ClesCindyZOUK100% (1)

- Trademark Bullying & The Streisand Effect (Erik Pelton - NYSBA 2012 IP Conference)Document14 pagesTrademark Bullying & The Streisand Effect (Erik Pelton - NYSBA 2012 IP Conference)Erik Pelton100% (1)

- Louis Vuittion ComplaintDocument35 pagesLouis Vuittion Complaintjeff_roberts881No ratings yet

- Bueckert REPLY FACTUM Main Motion - December 13, 2019Document10 pagesBueckert REPLY FACTUM Main Motion - December 13, 2019Michael BueckertNo ratings yet

- Gavin Sutter - Reforming English Libel LawDocument11 pagesGavin Sutter - Reforming English Libel Lawj_townendNo ratings yet

- Louis Vuitton Malletier v. Dooney & Bourke Inc. - Resisting Expan PDFDocument20 pagesLouis Vuitton Malletier v. Dooney & Bourke Inc. - Resisting Expan PDFDonette AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Rights LicensingDocument48 pagesRights LicensingRiko PiliangNo ratings yet

- Fake News: A Legal Perspective: InternetDocument9 pagesFake News: A Legal Perspective: InternetThales Vilela LeloNo ratings yet

- Dare Essay ExamplesDocument6 pagesDare Essay Examplesohhxiwwhd100% (2)

- Mostert and Schwimmer Vol101 - No1 - A14Document34 pagesMostert and Schwimmer Vol101 - No1 - A14mschwimmerNo ratings yet

- ViewcontenfrtrtDocument33 pagesViewcontenfrtrtpaulo da violaNo ratings yet

- Investor's Guide to Loss Recovery: Rights, Mediation, Arbitration, and other StrategiesFrom EverandInvestor's Guide to Loss Recovery: Rights, Mediation, Arbitration, and other StrategiesNo ratings yet

- The Pocket Legal Companion to Trademark: A User-Friendly Handbook on Avoiding Lawsuits and Protecting Your TrademarksFrom EverandThe Pocket Legal Companion to Trademark: A User-Friendly Handbook on Avoiding Lawsuits and Protecting Your TrademarksNo ratings yet

- Moodle Activity Task 3 TS311Document4 pagesMoodle Activity Task 3 TS311ADYNo ratings yet

- 2019 Inc Blue Green Confidential Info Friendly Lao Che Ii Christie'sDocument7 pages2019 Inc Blue Green Confidential Info Friendly Lao Che Ii Christie'sJonathan Hendson PassagiNo ratings yet

- AndreadvproDocument10 pagesAndreadvproapi-252679230No ratings yet

- Klein, Naomi - Signs of The Times (2001)Document9 pagesKlein, Naomi - Signs of The Times (2001)Thomas BlonskiNo ratings yet

- Mutual Fund Industry Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for Investment ProfessionalsFrom EverandMutual Fund Industry Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for Investment ProfessionalsNo ratings yet

- Running Head: HOMEWORK 2Document11 pagesRunning Head: HOMEWORK 2AndrewUhlenkampNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Essentials of Contemporary Business 1st Edition Boone Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Essentials of Contemporary Business 1st Edition Boone Test Bank PDFroestonefootingps8ot100% (9)

- 2 28 20 With BoxesDocument10 pages2 28 20 With BoxesMike LienNo ratings yet

- Fake News Types and ResponsesDocument20 pagesFake News Types and ResponsesLiway Czarina S RuizoNo ratings yet

- Luxury Brand Strategy of Louis VuittonDocument10 pagesLuxury Brand Strategy of Louis VuittonPaula Yagüe100% (1)

- Chucky and Some Fake Left FriendsDocument673 pagesChucky and Some Fake Left FriendsDavid Raymond AmosNo ratings yet

- Insider Trading Chapter - 11Document41 pagesInsider Trading Chapter - 113282672No ratings yet

- Online Essay ScorerDocument5 pagesOnline Essay Scorerwavelid0f0h2100% (2)

- Borjal V CaDocument14 pagesBorjal V CaKPPNo ratings yet

- Benetton's Controversial Advertising Strategy Raises Global AwarenessDocument3 pagesBenetton's Controversial Advertising Strategy Raises Global AwarenesschazmynNo ratings yet

- Cheng Lu Wang - The Palgrave Handbook of Interactive Marketing-Palgrave Macmillan (2023)Document1,067 pagesCheng Lu Wang - The Palgrave Handbook of Interactive Marketing-Palgrave Macmillan (2023)WalterNo ratings yet

- Financial Cold War: A View of Sino-US Relations from the Financial MarketsFrom EverandFinancial Cold War: A View of Sino-US Relations from the Financial MarketsNo ratings yet

- David Levine's Claims on How Patents Harm SocietyDocument3 pagesDavid Levine's Claims on How Patents Harm SocietytobiasmaveryNo ratings yet

- Product Placement - Embedded Advertising Filing (PFF)Document7 pagesProduct Placement - Embedded Advertising Filing (PFF)Adam Thierer100% (1)

- Obscene Billboards Social Perception PhilippinesDocument10 pagesObscene Billboards Social Perception PhilippinesRaymart Zervoulakos IsaisNo ratings yet

- The Vital Two - Retail Innovation by Sol Price and Sam WaltonDocument22 pagesThe Vital Two - Retail Innovation by Sol Price and Sam WaltonLuís LeiteNo ratings yet

- News in Brief 4: Microsoft'S Linkedin Pulls Out of ChinaDocument2 pagesNews in Brief 4: Microsoft'S Linkedin Pulls Out of ChinaOtakuki UtsNo ratings yet

- Manu International, S.A. v. Avon Products, Inc., 641 F.2d 62, 2d Cir. (1981)Document9 pagesManu International, S.A. v. Avon Products, Inc., 641 F.2d 62, 2d Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 501 550Document23 pages501 550Ridz TingkahanNo ratings yet

- fl24 LabelDocument11 pagesfl24 LabelMike LienNo ratings yet

- Ponzi Scheme Paper1Document4 pagesPonzi Scheme Paper1Junius Markov OlivierNo ratings yet

- Fatimah Chau - Sukd1902342Document13 pagesFatimah Chau - Sukd190234211 ChiaNo ratings yet

- 13928-Article Text-10689-1-10-20150624Document7 pages13928-Article Text-10689-1-10-20150624Agnes MalkinsonNo ratings yet

- Intelligence Briefs or DisinformationDocument4 pagesIntelligence Briefs or Disinformationhalojumper63No ratings yet

- Online Defamation LawDocument6 pagesOnline Defamation LawMark Darren LantinNo ratings yet

- LSE MPP Policy Brief 20 - Fake News - FinalDocument20 pagesLSE MPP Policy Brief 20 - Fake News - FinalrameshnuvkekaNo ratings yet

- The Virtual Legal MarketplaceDocument5 pagesThe Virtual Legal MarketplaceOmar Ha-RedeyeNo ratings yet

- Property Case Brief 6Document2 pagesProperty Case Brief 6tennis123123No ratings yet

- The Tort of DefamationDocument14 pagesThe Tort of DefamationPranjal Srivastava100% (2)

- Michael Lewis’ Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt | SummaryFrom EverandMichael Lewis’ Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt | SummaryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Selling America Short: The SEC and Market Contrarians in the Age of AbsurdityFrom EverandSelling America Short: The SEC and Market Contrarians in the Age of AbsurdityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Benetton: The Cause, The Creative, The ControversyDocument4 pagesBenetton: The Cause, The Creative, The ControversyEdward_Boches_4072No ratings yet

- Boottique IP v. Forever 21 Et. Al.Document9 pagesBoottique IP v. Forever 21 Et. Al.PriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Corporate Fraud and Internal Control Workbook: A Framework for PreventionFrom EverandCorporate Fraud and Internal Control Workbook: A Framework for PreventionNo ratings yet

- NR Occ 2021 2aDocument10 pagesNR Occ 2021 2aMichaelPatrickMcSweeneyNo ratings yet

- Colman, "Patents and Perverts" Presentation at University of Quebec at Montreal (May 14, 2015)Document23 pagesColman, "Patents and Perverts" Presentation at University of Quebec at Montreal (May 14, 2015)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- OCC, Interpretive Letter 1170 - Authority of A National Bank To Provide Cryptocurrency Custody Services To Customers (July 22, 2020)Document11 pagesOCC, Interpretive Letter 1170 - Authority of A National Bank To Provide Cryptocurrency Custody Services To Customers (July 22, 2020)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- HM Treasury - UK Regulatory Approach To Cryptoassets and Stablecoins (Jan. 2021)Document46 pagesHM Treasury - UK Regulatory Approach To Cryptoassets and Stablecoins (Jan. 2021)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- CM Collections, Inc. v. CM Brand Holdings LLC Et Al., 651018-2015 (N.Y. Sup. CT.) (Amended Complaint, Filed April 14, 2015)Document38 pagesCM Collections, Inc. v. CM Brand Holdings LLC Et Al., 651018-2015 (N.Y. Sup. CT.) (Amended Complaint, Filed April 14, 2015)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Montres Breguet S.A. Et Al (Swatch) v. Samsung Electronics Co. LTD., 1-19-CV-01708 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 22, 2019) (Complaint)Document67 pagesMontres Breguet S.A. Et Al (Swatch) v. Samsung Electronics Co. LTD., 1-19-CV-01708 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 22, 2019) (Complaint)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- D'Almaine v. Boosey, (1835) 1 Y. & C. 288Document7 pagesD'Almaine v. Boosey, (1835) 1 Y. & C. 288Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Binance Sues ForbesDocument12 pagesBinance Sues ForbesForkLogNo ratings yet

- Duncan 2019-03-29 Order Granting Plaintiffs MSJDocument86 pagesDuncan 2019-03-29 Order Granting Plaintiffs MSJwolf woodNo ratings yet

- Charles E. Colman, "Managing Mazer: The History and Principles of American Copyright Protection For Fashion Design" (2016)Document58 pagesCharles E. Colman, "Managing Mazer: The History and Principles of American Copyright Protection For Fashion Design" (2016)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Brantley & Nickens v. Epic GamesDocument23 pagesBrantley & Nickens v. Epic GamesAdi Robertson100% (1)

- Catherine Malandrino v. ASL Holdings LLC Et Al., 651349-2015 (N.Y. Sup. CT.) (Summons and Complaint, Filed April 22, 2015)Document58 pagesCatherine Malandrino v. ASL Holdings LLC Et Al., 651349-2015 (N.Y. Sup. CT.) (Summons and Complaint, Filed April 22, 2015)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- John Lamb's Case, 77 Eng. Rep. 822, 9 Coke 59 (Star Chamber 1610) .Document2 pagesJohn Lamb's Case, 77 Eng. Rep. 822, 9 Coke 59 (Star Chamber 1610) .Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Corker v. Costco, 2:19-cv-00290 (W.D. Wash.) (Complaint, Filed Feb. 27, 2019)Document65 pagesCorker v. Costco, 2:19-cv-00290 (W.D. Wash.) (Complaint, Filed Feb. 27, 2019)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Charles E. Colman, "Thomas Dreams of Separability" (2018)Document18 pagesCharles E. Colman, "Thomas Dreams of Separability" (2018)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Emily Post, Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home (1922) PDFDocument677 pagesEmily Post, Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home (1922) PDFCharles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- "Costume History - Contemporary Dress" (ARCS-GE 2064) - Final Syllabus For NYU Graduate-Level Fashion Theory SeminarDocument3 pages"Costume History - Contemporary Dress" (ARCS-GE 2064) - Final Syllabus For NYU Graduate-Level Fashion Theory SeminarCharles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Cartier Creation Studio v. Lugano Diamonds, 8-15-CV-00838 (C.D. Cal.) (Complaint, Filed May 28, 2015)Document15 pagesCartier Creation Studio v. Lugano Diamonds, 8-15-CV-00838 (C.D. Cal.) (Complaint, Filed May 28, 2015)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Chanel, Inc. v. Chanel's Salon, LLC, 2-14-CV-00304 (N.D. Ind.) ('Judgment On Consent')Document9 pagesChanel, Inc. v. Chanel's Salon, LLC, 2-14-CV-00304 (N.D. Ind.) ('Judgment On Consent')Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Chanel, Inc. v. Chanel's Salon, LLC, 2-14-CV-00304 (N.D. Ind.) (Pro Se Litigant's 'Answer' To Complaint)Document1 pageChanel, Inc. v. Chanel's Salon, LLC, 2-14-CV-00304 (N.D. Ind.) (Pro Se Litigant's 'Answer' To Complaint)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- USPTO Office Action - Katy Perry Left Shark Trademark Application (Serial Number 86529321)Document8 pagesUSPTO Office Action - Katy Perry Left Shark Trademark Application (Serial Number 86529321)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- USPTO Office Action - Katy Perry Left Shark Trademark Application (Serial Number 86529321)Document8 pagesUSPTO Office Action - Katy Perry Left Shark Trademark Application (Serial Number 86529321)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Chanel, Inc. v. Heller, 1-14-CV-08011-JGK (S.D.N.Y.) (Notice of Voluntary Dismissal With Prejudice)Document1 pageChanel, Inc. v. Heller, 1-14-CV-08011-JGK (S.D.N.Y.) (Notice of Voluntary Dismissal With Prejudice)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Chanel, Inc. v. Jeanine Heller D/b/a What About Yves, 1:14-CV-08011-JGK (S.D.N.Y.) (Order For Pre-Motion Conference, Oct. 27, 2014)Document2 pagesChanel, Inc. v. Jeanine Heller D/b/a What About Yves, 1:14-CV-08011-JGK (S.D.N.Y.) (Order For Pre-Motion Conference, Oct. 27, 2014)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Charles E. Colman, "Patents and Perverts" (Presentation On Work-In-Progress, Given at Nov. 2014 Marquette Law "Mosaic" Conference)Document33 pagesCharles E. Colman, "Patents and Perverts" (Presentation On Work-In-Progress, Given at Nov. 2014 Marquette Law "Mosaic" Conference)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Chanel, Inc. v. Heller, 1:14-CV-08011-JGK (S.D.N.Y.) (Filed Oct. 19, 2014) (Notice of Appearance For Charles Colman)Document2 pagesChanel, Inc. v. Heller, 1:14-CV-08011-JGK (S.D.N.Y.) (Filed Oct. 19, 2014) (Notice of Appearance For Charles Colman)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Mori Lee, LLC v. Sears Holdings Corp., 13-CV-3656 (S.D.N.Y. Sep. 8, 2014)Document9 pagesMori Lee, LLC v. Sears Holdings Corp., 13-CV-3656 (S.D.N.Y. Sep. 8, 2014)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Chanel, Inc. v. Jeanine Heller D/b/a What About Yves, 1-14-CV-08011-JGK (S.D.N.Y.) (Complaint, Filed 10-3-14)Document56 pagesChanel, Inc. v. Jeanine Heller D/b/a What About Yves, 1-14-CV-08011-JGK (S.D.N.Y.) (Complaint, Filed 10-3-14)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- David Yurman v. Sam's Club Complaint (S.D. Tex.)Document17 pagesDavid Yurman v. Sam's Club Complaint (S.D. Tex.)Charles E. ColmanNo ratings yet

- Business Plan - Lubricants Trading & WholesellingDocument13 pagesBusiness Plan - Lubricants Trading & WholesellingNajam Khan80% (5)

- Container Loading Supervisor Sample ReportDocument13 pagesContainer Loading Supervisor Sample ReportVivek S SurendranNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 - Eval. of MediaDocument24 pagesUnit 7 - Eval. of MediaTara RastogiNo ratings yet

- Inventory Management: Presented ByDocument11 pagesInventory Management: Presented ByChandan DuttaNo ratings yet

- Sartika Muslimawati (Tugas Man Pemasaran) MIXDocument12 pagesSartika Muslimawati (Tugas Man Pemasaran) MIXSartika muslimawatiNo ratings yet

- MKT203 Marketing Mix Management End-of-Course AssessmentDocument9 pagesMKT203 Marketing Mix Management End-of-Course AssessmentJeffrey KohNo ratings yet

- Study The Impact of Social Media On Consumer Buying Behaviour and Its Effects With The Consumer of Uttarakhand StateDocument4 pagesStudy The Impact of Social Media On Consumer Buying Behaviour and Its Effects With The Consumer of Uttarakhand StateInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Marketing ProcessDocument12 pagesMarketing ProcessDEEPAK09SAININo ratings yet

- Capturing and nurturing leads with marketing automationDocument55 pagesCapturing and nurturing leads with marketing automationJoao Paulo MouraNo ratings yet

- Media Buying & Agency DecisionsDocument19 pagesMedia Buying & Agency Decisionsimran8392No ratings yet

- Personal SWOT Analysis and Analysis of Wal-MartDocument10 pagesPersonal SWOT Analysis and Analysis of Wal-MartAli RehmatNo ratings yet

- Economics For Managers - Session 11Document16 pagesEconomics For Managers - Session 11Abimanyu NNNo ratings yet

- Digital Marketing CV ResumeDocument1 pageDigital Marketing CV ResumeMehedi HassanNo ratings yet

- Tybms SM 3 PDFDocument32 pagesTybms SM 3 PDFkamlesh rajputNo ratings yet

- Factors That Affect Marketing MixDocument11 pagesFactors That Affect Marketing Mixmanjusri lalNo ratings yet

- Current Focus On Management AccountingDocument3 pagesCurrent Focus On Management AccountingGêmTürÏngånÖ0% (2)

- Bagnol FSDocument55 pagesBagnol FSRosemarie EspinaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - MerchandisingDocument44 pagesChapter 6 - MerchandisingMaria FransiscaNo ratings yet

- Self-Appraisal Negotiation Skills PaperDocument20 pagesSelf-Appraisal Negotiation Skills PaperAshishPareekNo ratings yet

- ASSESSMENT XII B.INGGRIS 2024 - Google FormulirDocument43 pagesASSESSMENT XII B.INGGRIS 2024 - Google FormulirreilinoorNo ratings yet

- CarlsbergDocument8 pagesCarlsbergmheeisnotabear0% (1)

- Session 12 - Marketing - Helping Buyers BuyDocument36 pagesSession 12 - Marketing - Helping Buyers BuyAprilia FransiskaNo ratings yet

- Essay About PatriotismDocument4 pagesEssay About Patriotismafhbebhff100% (2)

- Media Management Unit 1 Organizational Behavior: Importance of OBDocument48 pagesMedia Management Unit 1 Organizational Behavior: Importance of OBRosariomerko100% (1)

- Discourse Community EssayDocument3 pagesDiscourse Community Essayapi-302842071No ratings yet

- BFPMDocument12 pagesBFPMMiltonThitswaloNo ratings yet

- How To Become A Business Coach v7Document107 pagesHow To Become A Business Coach v7ken100% (3)

- Fixed Amount Award TemplateDocument9 pagesFixed Amount Award TemplateJuan Carlos FiallosNo ratings yet

- Kotler - mm14 - ch10 - DPPT - Crafting The Brand PositionDocument26 pagesKotler - mm14 - ch10 - DPPT - Crafting The Brand PositionRangga BrasisNo ratings yet