Professional Documents

Culture Documents

All Quiet On The Western Front Essay

Uploaded by

Mircsi MatuskaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

All Quiet On The Western Front Essay

Uploaded by

Mircsi MatuskaCopyright:

Available Formats

The social effects of war in All Quiet on the Western Front

All Quiet on the Western Front is not just one of the many books about the First World War. While the others were mostly about memoirs, Remarque rather dealt with the social effects of the war. Even though, he stated in the motto of the book that he is not intending to accuse anybody or confess, he is. The books emphasis is not on the war but on its impacts on the people and All Quiet on the Western Front is indeed an accusation for destroying people not only physically but especially mentally. The main theme of the book is the meaninglessness of the war, and the changes that take place in the souls of the soldiers. Eksteins (345) says that the boom of war-related art started at the end of the 1920s. Before that, war was mostly a taboo. People wanted to forget and look into the future. War was still in peoples minds, remembering was still too painful. There was a nervous exhaustion from which nations suffered after the war. (346) The interest started to evoke around 1928. Books, plays, films about the Great War became a fashionable subject. Ten years passed since the end of the war, when books got published about it, war dramas were staged in a high number, war movies flooded the cinemas: suddenly everything in connection with the war became saleable and popular. This was the trend mainly in Germany and GreatBritain, but also in France and in the United States (345-347). Remarques war experience is quite mysterious. As he was born in 1989, he was 16, when the war broke out in 1914. He was conscripted two years later, in 1916. He is said to be wounded five or six times, but only one of these was serious. After wounding in his leg and under his arm, he got hospitalized in Duisburg till the end of the war. His days as a soldier are little-known, but his war experience was definitely not as extensive as that of the main character, Paul. After the war, he tried to write poems, novels and plays and he finally published only two novels, but none of them became really popular (Eksteins 348). His life

was not successful after the war, and in an interview he admitted [a]ll of us were and still are, restless, aimless, sometimes excited, sometimes indifferent, and essentially unhappy. (349) That is probably where the inspiration to the book came from. The novel starts with the following motto: This book is to be neither an accusation nor a confession, and least of all an adventure, for death is not an adventure to those who stand face to face with it. It will try simply to tell of a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped its shells, were destroyed by the war. It is already revealed here that Remarque does not want to deal with actual facts, but rather with the impacts of the war. Although, he says that the book is neither an accusation nor a confession, after reading it, it becomes obvious that it is indeed both. Eksteins states that Remarque confesses his personal despair, and accuses the wrong social and political order that produced the war and the horror that came with it. (351) His point is that there were soldiers who returned home, however, they were mentally destroyed by their experiences. They could never be the same people they were before. As Ekstein puts it into words: the war has destroyed the ties, psychological, moral, and real, between the front generation and society at home. (351) Throughout the novel there are many scenes that are intended to show this irreversible change in soldiers, which makes it impossible for them to return to their homes and live their lives as they lived before the war. This is showed through the example of the main character, Paul Buman, who might be based on Remarque himself, whose middle name was originally Paul (Eksteins 347). The most obvious change that the comrades go through is growing up. Paul and his classmates are 18 years old, and when we get to know them they are on the front for about 2 years. But they are not young anymore. We are none of us more than twenty years old. But

young? Youth? That is long ago. We are old folk. (Remarque 19) This topic comes up later as well, when thinking about what has happened since they are at the front: We were eighteen and had begun to love life and the world; and we had to shoot it to pieces. The first bomb, the first explosion, burst in our hearts. (66) Paul describes the change on the front a couple of times as becoming animals: we reach the zone where the front begins and become on the instant human animals. (Remarque 44) Soldiers do not think any more, because if they did, they would go insane. They become mindless killing-machines. It is not against men that we fling our bombs, what do we know of men in this moment when Death is hunting us down. (83) At least, they try not to think about killing, because if they do, it reminds them of their mortality. It happens, when Paul goes out spying after his days off, and stabs a French soldier (152) or when he catches the eye of a soldier from the enemy (82). The question of survival became their law: either the enemy or them and they cannot let themselves pity the enemy: if we don't destroy them, they will destroy us. (Remarque 84) The comrades lost their feelings and emotions and that is how they are still able to go on and kill. Otherwise, it would be impossible, and Paul perfectly describes this state of mind: We have lost all feeling for one another. We can hardly control ourselves when our glance lights on the form of some other man. We are insensible, dead men, who through some trick, some dreadful magic, are still able to run and to kill. (84) In contrast with the animal-metaphor, while they totally alienate from their natural self, nature and animals live their normal life. Seasons are changing, animals are building their nests and then hatch the eggs. There are some brimstone-butterflies, although there are no flowers (Remarque 93). Seeing the normal life of nature, the horror of war and the changes it brought seem even more unnatural and abnormal.

Another contrast is the one between quiet and noise. The normal life is quiet. When Paul remembers some nice memories, he says that they are always quiet, even if they were louder in reality. But at the front there is no quietness. (Remarque 91) When Paul is spending his days off, he is frightened by the noisy of the tram. Sudden noises will always mean the war for him, even if there is peace. Home becomes alien and strange. Paul does not feel what he used to feel. He tries really hard, but he cannot get that feeling again. Nothing has changed, but him. Even he knows that: I find I do not belong here any more, it is a foreign world. (Remarque 120). The front is their new home. It has its own rules and its own value system, where they do not have any comfort, but their comrades. They are more to me than life, these voices, they are more than motherliness and more than fear; they are the strongest, most comforting thing there is anywhere: they are the voices of my comrades. Berkley also emphasizes that the friendship with Kat, who became the most important person in the life of Paul (71). When Paul returns home, first he does not even know how to behave. No one can understands him. Even if they know what is going on at the front, they are unable to grasp it. When Pauls mother is asking her son, if it was really bad out there, he thinks: Mother, what should I answer to that! You would not understand, you could never realise it. And you never shall realise it. Was it bad, you ask.--You, Mother,--I shake my head and say: "No, Mother, not so very. There are always a lot of us together so it isn't so bad." (Remarque 115) Even those, who are the closest to Paul cannot understand the horror of the war. Only those can who are out there fighting and lived through it (Delahunty and Yoo 923). This not-understanding is even worse in the case of strangers. When Paul meets his German teacher, and the head-master of his school, they seem to understand even less. Paul tries to explain them how bad the situation is, but his efforts are in vain. These two people

only laugh, and think that they can win with a little more effort. They say they understand, but they would not say things like that, if they really could.(Remarque 118). Returning their previous life is impossible for the soldiers, because they gained characteristics that are essential to survival and war. Things without which, they would go insane or die, but attributes that are not only useless in normal life, but make life much harder. Remarque also gives these words into Pauls mouth: We became hard, suspicious, pitiless, vicious, tough - and that was good; for these attributes were just what we lacked. Had we gone into the trenches without this period of training most of us would certainly have gone mad. (Remarque 24) The soldiers does not realize but the war was the meaning of their lives (Delahunty and Yoo 925), which loses its meaning the minute they return home. The other thing that Remarque wants to prove is that war is meaningless. There is a scene in the book, when one of Pauls comrades called Kropp is wondering about this. He implies that both countries think that are right and that they are the only one that is right. He is also thinking about why the war started. Someone says it is patriotism, because one country offended the other, but Kropp reaches the conclusion that it still does not make sense because he personally not offended (Remarque 142-145). These people are those that give the commands that influences the lives of all the soldiers: A word of command has made these silent figures our enemies; a word of command might transform them into our friends. (146) At an earlier point, the comrades are daydreaming about a war where only the actual parties would take part: Then in the arena the ministers and generals of the two countries, dressed in bathing-drawers and armed with clubs, can have it out among themselves. Whoever survives, his country wins. (32) Paul gradually starts to understand the impacts of the war on himself, and sometimes, he is thinking about them. He already knows what he would experience going back to society, and he puts it into words a couple of times. In the last chapter he concludes: Now if we go

back we will be weary, broken, burnt out, rootless, and without hope. We will not be able to find our way any more. (Remarque 199) It is the way Remarque wants to emphasize it. He does not only show it in action, but also gives the actual words into Pauls mouth. Paul symbolizes the average soldier. He got conscripted from high school at the age of 18. He is believable, sensitive, and intelligent but not remarkably different from his companions. (Berkley 71) He is gradually changing, as he sees his friend die, then himself kills an another soldier by stabbing him. This is a change that might slow down when he goes home, but it cannot be turned back. The structure of the book also highlights the meaninglessness of the war. Berkley says that there is no real plot, the book is written in journalistic style. There are some recurrent images (such as eating or bombings), which makes the novel rather a circular narrative then one that consists of causes and effects. It reflects the nature of the war that it is unpredictable, and pointless. (71) The first person singular narration and the present tense evoke immediacy that is also a feature of war. Also the language and the gruesome images reflect the horror of the war (Eksteins 350). Even though, the main character and his friends are German, it is not very much emphasized. They could be French, as well as English or Americans. It does not matter, because results of the war are the same for all country. A generation that grew up in the war, survived it, but is mentally destroyed, it is the common fate of our generation. (Remarque 65) To summarize, Erich Maria Remarques purpose with this book was showing how pointless the war is, and how it destroys even those who survive it. All Quiet on the Western Front is not only a description of the war, but also an accusation of the order that makes people kill each other. The authors point is very clear, he emphasizes it in the scenes of the book, characters say it out loud, and even the novels structure and style highlights it.

Works Cited Berkley, June. "Recommended: Erich Maria Remarque ." National Council of Teachers of English 75.5 (1986): 71-72. JSTOR. Web. 20 Mar. 2013. Delahunty, Robert J., and John C. Yoo. "Peace through Law? The Failure of a Noble Experiment." The Michigan Law Review Association 106.6 (2008): 923-39. JSTOR. Web. 20 Mar. 2013. Eksteins, Modris. "All Quiet on the Western Front and the Fate of a War." Journal of Contemporary History 15.2 (1980): 345-66. JSTOR. Web. 20 Mar. 2013. Remarque, Erich Maria. All Quiet on the Western Front. London: Putnam & Company Ltd., 1970. Print

You might also like

- The Officers' Ward by Marc Dugain (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideFrom EverandThe Officers' Ward by Marc Dugain (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNo ratings yet

- All Quiet On The Western Front Critical AnalysisDocument11 pagesAll Quiet On The Western Front Critical AnalysisMonica KempskiNo ratings yet

- All Quiet On The Western FrontDocument6 pagesAll Quiet On The Western Frontapi-405719582No ratings yet

- "Refugee Blues" by W.H. Auden: A Marxist AnalysisDocument7 pages"Refugee Blues" by W.H. Auden: A Marxist AnalysisAnafeNo ratings yet

- All Quiet Owf LyonsDocument4 pagesAll Quiet Owf Lyonsapi-315071293No ratings yet

- All Quiet On The Western FrontDocument19 pagesAll Quiet On The Western FrontAcademicPaperWritersUKNo ratings yet

- All Quiet UnitDocument23 pagesAll Quiet UnitpodellNo ratings yet

- Slaughterhouse 5 WorksheetDocument14 pagesSlaughterhouse 5 Worksheetrox58No ratings yet

- How War Transforms Paul in All Quiet on the Western FrontDocument3 pagesHow War Transforms Paul in All Quiet on the Western FrontRida HamidNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For All Quiet On The Western FrontDocument8 pagesThesis Statement For All Quiet On The Western FrontHelpInWritingPaperIrvine100% (2)

- All Quiet EssayDocument5 pagesAll Quiet EssayKenny XuNo ratings yet

- All Quiet: Humanity and Propaganda in WarDocument9 pagesAll Quiet: Humanity and Propaganda in WarDan LeNo ratings yet

- All Quiet in The Western FrontDocument7 pagesAll Quiet in The Western FrontJohn FaustusNo ratings yet

- All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideFrom EverandAll Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNo ratings yet

- All Quiet On The Western FrontDocument9 pagesAll Quiet On The Western FrontLore WheelockNo ratings yet

- MWSGDocument8 pagesMWSGapi-244470959No ratings yet

- Thesis Statement All Quiet On The Western FrontDocument8 pagesThesis Statement All Quiet On The Western Frontpbfbkxgld100% (2)

- The Impact of Wars On Soldiers Presented in "The Things They Carried" and "My Oedipus Complex"Document6 pagesThe Impact of Wars On Soldiers Presented in "The Things They Carried" and "My Oedipus Complex"Toony WatooNo ratings yet

- All Characterization On The Theme Front Rewrite 1Document5 pagesAll Characterization On The Theme Front Rewrite 1api-611293197No ratings yet

- Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five Themes of Time, Fate and the Absurdity of WarDocument4 pagesVonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five Themes of Time, Fate and the Absurdity of WarcrazybobblaskeyNo ratings yet

- All Quiet On The Western Front Thesis EssayDocument7 pagesAll Quiet On The Western Front Thesis EssayINeedSomeoneToWriteMyPaperOlathe100% (2)

- AQWFDocument2 pagesAQWFAlex Jr ValtierraNo ratings yet

- 39 Most Widely Read War Novels: Introduction and Plot SummariesFrom Everand39 Most Widely Read War Novels: Introduction and Plot SummariesNo ratings yet

- All Quiet On The Western Front NotesDocument37 pagesAll Quiet On The Western Front NotesSukhvir AujlaNo ratings yet

- Pollock Essaay #1 HeroDocument3 pagesPollock Essaay #1 HeroJimin YoonNo ratings yet

- Thesis All Quiet On The Western FrontDocument6 pagesThesis All Quiet On The Western FrontLuisa Polanco100% (2)

- Annotated BibliographyDocument6 pagesAnnotated Bibliographysmei91No ratings yet

- J HellerDocument15 pagesJ HellerslnkoNo ratings yet

- Anti War Literature by SnigdhaDocument31 pagesAnti War Literature by SnigdhaSuhas Sai MasettyNo ratings yet

- Vonnegut's Themes in Slaughterhouse-FiveDocument10 pagesVonnegut's Themes in Slaughterhouse-FiveRocio TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Héctor Germán Oesterheld: Ethics and Aesthetics of A HumanistDocument25 pagesHéctor Germán Oesterheld: Ethics and Aesthetics of A HumanistGeovanaNo ratings yet

- Front. The Real Enemy That Every Soldier Fights Against in War Is Death, Not Other SoldiersDocument2 pagesFront. The Real Enemy That Every Soldier Fights Against in War Is Death, Not Other SoldiersLewisBackNo ratings yet

- Formal Reading ResponseDocument3 pagesFormal Reading Responseapi-282220582No ratings yet

- English Poetry EssayDocument6 pagesEnglish Poetry Essayapi-263631130No ratings yet

- Finding Meaning After The ApocalypseDocument5 pagesFinding Meaning After The ApocalypseMiroslav CurcicNo ratings yet

- Animal Farm IntroductionDocument4 pagesAnimal Farm Introductionngr415826No ratings yet

- John-Nicholas Furst Ms. Hallinan H. Intro To Lit, C Block 25 April 2006 Independent Reading ProjectDocument5 pagesJohn-Nicholas Furst Ms. Hallinan H. Intro To Lit, C Block 25 April 2006 Independent Reading ProjectjnfurstNo ratings yet

- IOOutline 2Document2 pagesIOOutline 2Gagan GuttaNo ratings yet

- The Missing Soldier Sad StoryDocument38 pagesThe Missing Soldier Sad StoryArman UmarNo ratings yet

- Anti War Literature Project by Namratha.NDocument32 pagesAnti War Literature Project by Namratha.NSuhas Sai MasettyNo ratings yet

- TTTC PaperDocument4 pagesTTTC Paperapi-462976730No ratings yet

- Kurt Vonnegut (From Norton)Document3 pagesKurt Vonnegut (From Norton)Marcin DąbekNo ratings yet

- Poetry Project: in Flanders FieldsDocument12 pagesPoetry Project: in Flanders FieldsdecstuffNo ratings yet

- Horrors of WarDocument7 pagesHorrors of WarConnor McKiernanNo ratings yet

- FutilityDocument4 pagesFutilityLungmuaNa RanteNo ratings yet

- Analyze A Piece of Satire About A Significant Cultural Event and Discuss The Larger Role Satire Does and Should Play in CultureDocument5 pagesAnalyze A Piece of Satire About A Significant Cultural Event and Discuss The Larger Role Satire Does and Should Play in CulturebartekNo ratings yet

- War by Luigi PirandelloDocument13 pagesWar by Luigi PirandelloSofia Reinne Ong LafortezaNo ratings yet

- "A FAREWELL TO ARMS" Presents A Pessimistic OutlookDocument6 pages"A FAREWELL TO ARMS" Presents A Pessimistic OutlookKiran.A.K.L100% (2)

- Remote Learning Week 3 AssignmentDocument4 pagesRemote Learning Week 3 AssignmentAndrew MNo ratings yet

- Catch 22analysisDocument10 pagesCatch 22analysisapi-133757105No ratings yet

- 'Anthem For Doomed Youth' SummaryDocument4 pages'Anthem For Doomed Youth' Summaryzaid aliNo ratings yet

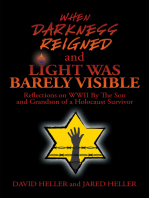

- When Darkness Reigned and Light Was Barely Visible: Reflections on Wwii by the Son and Grandson of a Holocaust SurvivorFrom EverandWhen Darkness Reigned and Light Was Barely Visible: Reflections on Wwii by the Son and Grandson of a Holocaust SurvivorNo ratings yet

- WW2NewsLetterVol#2 No.12Document3 pagesWW2NewsLetterVol#2 No.12njww2bookclubNo ratings yet

- All Quiet On The Western Front Book ReportDocument3 pagesAll Quiet On The Western Front Book ReportYuman LiNo ratings yet

- Strange Meeting: Wilfred Owen's Poem on the Horrors of WWIDocument9 pagesStrange Meeting: Wilfred Owen's Poem on the Horrors of WWIDhyana Buch100% (1)

- Ann Radcliffe: Mysteries of UdolphoDocument477 pagesAnn Radcliffe: Mysteries of UdolphoMircsi MatuskaNo ratings yet

- W.H. Edwards Relating To The PastDocument10 pagesW.H. Edwards Relating To The PastMircsi MatuskaNo ratings yet

- Aliens - The Anthropology of Science FictionDocument176 pagesAliens - The Anthropology of Science FictionOZar15100% (2)

- The Theme of Becoming Human in Stephenie Meyer's The HostDocument6 pagesThe Theme of Becoming Human in Stephenie Meyer's The HostMircsi MatuskaNo ratings yet

- PersuasionDocument254 pagesPersuasionRishabh BangarNo ratings yet

- All Quiet On The Western Front EssayDocument7 pagesAll Quiet On The Western Front EssayMircsi MatuskaNo ratings yet