Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History of The Delaware Bay Oyster Industry PDF

Uploaded by

EarlOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

History of The Delaware Bay Oyster Industry PDF

Uploaded by

EarlCopyright:

Available Formats

History of the Delaware Bay Oyster Industry Oysters reefs were found from the mouth of the Delaware

Bay to Woodland Beach, on the western (Delaware) side of the estuary, and in New Jersey; from Artificial Island on the eastern side, a distance of about 50 miles. These reefs for several hundreds of years provided a sustainable food supply, and contributed to the local economy of Kent County and New Castle Delaware, along with most of the counties in New Jersey, sharing the Delaware Bay and River for centuries. From the mid-1800's to the first quarter of the Twentieth Century, oysters were a popular seafood in the United States so abundant, you would find oyster carts dotting the streets of Wilmington, DE and Philadelphia like the fast food chains you see today. This was the food of people from all walks of life from the connoisseurs to the blue collar workers, young children to convalescents alike enjoyed the Delaware Bay bivalves. Easily eaten, and high in quality protein making them great snacks for people in a hurry. In the early years of the fishing industry of the Delaware Bay and River, the oyster industry produced an annual average of 9.2 million pounds of product worth $1,600,000 (Today that figure would be nearly $1.5 Billion adjusted for inflation). Shucking and seafood processing plants began to be built along the coastline, and soon after, opened for business hiring tens of thousands of people along both the New Jersey and Delaware sides of the Delaware Bay, creating jobs the economy from the fishing industry boomed. Entire towns began sprouting up up around the oyster industry: Port Norris, Bivalve, Shellpile, and Maurice River in South Jersey; Bowers Beach, Leipsic, Woodland Beach Delaware City Augustine Beach, and Little Creek in Delaware. At the peak of the oyster fishery, Port Norris could claim more millionaires than any other town in New Jersey! The prosperity extended throughout the region, even as far as Philadelphia, where some business and ship shareholders were based. Shops and services sprang up in the small towns along the Bay from Ship building. People flocked into the region because of the employment opportunities and a chance to share in the good life. On the Delaware Bay, oysters are usually dredged from "Seed" beds in the spring and "Planted" on other beds to grow out to market size (3" is the legal minimum). Oyster planting in the Delaware Bay was first done in the 1820s in Port Mahon, Woodland Beach, and Little Creek in Delaware. In the late 1940's, dredging under power began, most of the old schooners cut down their masts, converting to power, which allowed the watermen to harvest more oysters with less effort. within a few short years (the late 1950s), Delaware Bay oystering collapsed, due to overharvesting and then a new found enemy to the oyster; the oyster disease MSX (Haplosporidium nelsoni) a microscopic parasite too small to see with the naked eye. What is MSX The parasite first enters the oysters tissues it multiplies and then spreads. The plasmodial stages can be found throughout the soft tissues of the oyster, and by the end of the summer spore stages MSX begins developing inside the walls of the digestive tubules. All this causes tissue damage that gradually weakens of the oysters until they ultimately begin dying at the end of the

summer.The oyster catches around 1957 dropped 98% in two seasons and never recovered. The loss of the oyster business turned many south Jersey and Delaware communities into ghost towns. The MSX and Dermo organisms where first discovered in the Delaware Bay, some experts beleve the diseases could have come to the Delaware Bay from elsewhere in the world on ships (i.e., in ballast water, or on oyster seeds brought into the bay, or oysters that were brought in by the public and "put over the side to keep."). Stress to the oysters from pollution or eroded sediment is also believed to weakened the oyster making them more susceptible to the disease. Other causes for the oyster depletion is possibly due to changes in salinity of the water where the oyster reefs were, caused by water use, and the removal of plant cover upstream; channel dredging may have also stressed the oysters or otherwise helped the diseases to spread.

Although, its not known for sure whether human activities promoted the spread of oyster diseases, its generally true; when an organism is stressed (by pollution, climate, inadequate food, etc.), it becomes more susceptible to disease or predation (so that in nature, weakened members of a species are often "weeded" out). So, an oyster choked by sediment or sickened by disease MAY be more likely to die of disease. Erosion of sediment (soil) from the land, especially land from which the natural plant cover has been removed is one of the problems for oysters. Sediment in the water will "choke" an oysters gills, slowing both its breathing and feeding ability. this sediment also settles out and covers oyster beds, cutting off their supply of clean, oxygen-containing water. Sediment excess can result in what is called Nonpoint Source Pollution (or NPS) One of the problems for oysters is the erosion of sediment (soil) from the land, especially land from which the natural plant cover has been removed. Sediment in the water can "choke" an oysters gills, slowing both breathing and feeding. It can also settle out and cover oyster beds, cutting off their supply of clean, oxygen-containing water. Sediment excess can result in what is called Nonpoint Source Pollution (or NPS), pollution that can't be traced back to a particular point. NPS pollution is primarily runoff from farms, streets, and lawns, where pesticides, fertilizers, oils, and other toxic materials are used, as well as sediment. Forests and wetlands tend to act as filters or sponges, absorbing rainwater and NPS pollution before reaching the River and Bay. Paved land doesnt absorb rainwater, instead funneling it runoff, along with the pollutants, carrying them directly into streams before being able to be filtered through the soil and plants. Oyster Biology/Pollution Effects Oysters live in shallow brackish or salty water growing in piles or clumps known as "beds." or "reefs" They require hard bottom habitat shell or rock. Oysters cannot survive being buried in the mud.

(Where is the natural hard bottom of the Delaware Bay?) One of the most interesting things about the oyster is that it can actually clean the water it lives in! Oysters feed by pumping water through its body-- filtering out its food. Oysters live on mostly algae and decaying plant material. A healthy oyster filters 50 or more gallons of water each day. Also, a natural oyster bed provides the habitat shelter and food for a community that includes many other organisms: plants, crabs, worms, and a variety fish: Croakers, Sturgeon, stripped bass, weakfish, Oyster Toadfish (oyster crackers), white and yellow perch, etc. Among other creatures you may see on an oyster reef are predators to the bivalve: oyster drills, moon snails, or whelks, snails that feed on oysters by drilling holes through the shells. The spat or larvae are very vulnerable. They are eaten by a wide variety of fish and invertebrates. Large oysters may be eaten by crabs, fish ( rays, skates, drum), starfish, worms, or birds (i.e., oystercatchers). Boring sponges are commensal, (use the shell as their home). They dont actually eat the oysters, but they can kill them. Oyster matting habits or reproduce mostly in summer, by releasing eggs and sperm into the water. Usually almost all the oysters in a bed will spawn at once once the water temperature reaches about 70 F. The fertilized eggs become larvae ("spat") that eventually settle and attach themselves ("set") to a hard bottom, (usually another oysters shell). Its important to return old shell to the oyster beds, a practice long ago started by the oystermen in the Delaware Bay.

Efforts were undertaken to escalate production and profit, but one factor working against the oystermen was the demand for shells to be ground into lime, depleting the shell supply needed to host seed oysters. State officials in 1846 decided to close the oyster beds that summer. Some oystermen began gathering a load of oysters and took them to Philadelphia and New York market, discovering they were overstocked. While returning home the oystermen dumped the bivalves nearby in deep water of the Bay. The following fall season they discovered that the oysters had fattened, and realized the potential of moving the small oysters from the shallow beds relocating them in deeper saltier waters of the Delaware Bay. Transplanting oysters became a widespread practice bolstering profitability, but depleted the natural beds in the shallower waters. Many seed oysters were also shipped to New England. As the shellfish continued to decline, oystermen had to go as far as Long Island Sound to acquire seed oysters for the following harvest. Sediment has also created new shoals (sand bars) and mud flats, and filled in many streams and channels. For example, Mauricetown was formerly a deepwater port for oceangoing ships, however, few of those ships could get there today. Other ports, and indeed the main River-Bay channel, need frequent dredging to keep them open. Perhaps the channel (and the transportation it allows) is too deep for the system to support? This dredging can cause sediment and other contaminants that have already settled out to be resuspended in the water, exposing oysters and other animals to the "recycled" pollution. Under-dredged ports lose their access to trade, and often become ghost towns. Funding Requirements

Recovery of the oyster industry of the Delaware Bay requires supplementing current funding with additional dollars to enhance production, support capacity building within the existing oyster resource management program, and expand market development efforts. These activities will provide the greatest economic return to the industry in the short term and establish the basis for a sustained, economically viable program. Estimated Return on Investment Coastal towns along the Delaware Bay developed as a direct result of the healthy oyster industry. Subsequent decline of the industry led to a high rate of unemployment and a drastic decline in the standard of living for many families with established roots in the region of Kent County and New Castle County. It is anticipated that given an initial input of state funds to bolster the oyster industry of the Delaware Bay, (targeting locations from Woodland Beach, to Bowers Beach,) within a five-year period, production can increase to between 200,000 and 330,000 bushels per year. It is also anticipated stabilization of supply and increased market development activities will result in a higher ex-vessel price ($51 per bushel). Using a conservative harvest and a very conservative ex-vessel value of $ 8million annually and applying a standard seafood economic multiplier of 6 The value of the industry to the state's economy is potentially $34 million annually. This is especially critical because these anticipated economic gains can be achieved in areas currently under severe economic stress. According to Delaware Department of Labor data released last week (July 14,-20 2013). Also anticipated; most dollars earned in the region will stay in the region supporting local small businesses. The value of the industry extends well beyond the oyster industry itself and extends to other waterfront activities such as shipbuilding and repair, preserving Delaware's maritime heritage through ecotourism and preservation of the maritime way of life. Given changes in environmental conditions and other natural variables, it is difficult to develop accurate projections of return on investment. However, even under the most conservative estimates, return on investment in the State's oyster industry is substantial.

History of the Delaware Oyster Industry Thomas Campanius Holm, an early Swedish settler, wrote in 1642 Delaware Bay oysters were "so very large that the meat alone is the size of our Oysters [Ostrea edulisl shell and all" (Ingersoll, 1881). A chart drawn by another Swede, Peter Lindestrom, between 1654 and 1656 showed the entire Delaware shore lined with oyster beds, as well as a large bed extending west from Cape May Point in New Jersey (Miller, 1962). Oysters from the bay were an important food source for early Dutch and Swedish colonists, and the establishment of British settlements along the bayshore later in the 1600s, especially the growth of Philadelphia as the region's largest city, fostered the beginning of commercial harvests. By the 1750s, fresh oysters from Delaware Bay were being shipped to

Philadelphia and New York (Smith, 1765), and pickled oysters, to the West lndies (Miller, 1962). The earliest oystermen were also farmers who probably gathered oysters from inshore areas using small boats and tongs; however, sloops and schooners capable of harvesting oysters from deep-water beds were built on the Cohansey River at Greenwich in the 1730s (Rolfs, 1971), and a 1777 map of New Jersey shows a large area of oyster beds offshore from Ben Davis Point. . By 1888, most of the harvest was shipped by rail (Nelson, 1889). Oysters harvested from Delaware waters continued to go by boat to Philadelphia or across the bay to Port Norris or Greenwich (Fig.A1--I), where they were shipped by train to Philadelphia (Ingersoll, 1881; Hall, 1894). Unlike New Jersey, the coastal railroad in Delaware served primarily to transport salt hay and agricultural produce. When lngersoll (1881) visited Delaware Bay in 1879-80, there were already nearly 1,400 vessels (about 300 of them sloops and schooners greater than 5 tons) and 2,300 men employed in taking oysters from the estuary.

Andrews, J. D. 1988. Epizootiology of the disease caused by the oyster pathogen Perkinsus marinus and its effects on the oyster industry. In W. S. Fisher (Editor), Disease processes in marine bivalve molluscs, p. 47-63. Am. Fish. Soc., Bethesda, Md. Ford, S.E. 1997. History and present status of molluscan shellfisheries from Barnegat Bay to Delaware Bay. In: The History, Present Condition, and Future of the Molluscan Fisheries of North and Central America and Europe, Vol. 1, North America (MacKenzie, C.L., Jr., V.G. Burrell Jr., A. Rosenfield and W.L. Hobart, Eds.) pp. 119-1 40. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Report NMFS, Seattle, Washington. Gall, K. and L. O'Dierno. 1994 . Aquaculture Marketing Survey -- Consumers, Retail Stores and Food Service in New York and New Jersey. Northeast Regional Aquaculture Center Publication. Hall, A. 1894. Oyster industry of New Jersey. In Report of the U.S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries for 1892, p. 463-528. US. Fish Comm., Wash., D.C. Haskin, H. H., and S. E. Ford. 1979. Development of resistance to Minchinia nelson (MSX) mortality in laboratory-reared and native oyster stocks in Delaware Bay. Mar. Fish. Rev. 41 (1 2):54-63. Haskin, H., H.A. Stecher, and N. Ismail. 1981. Oyster Drill Control by Hydraulic Dredging in Delaware Bay. Completion Report to the Department of Environmental Protection, State of New Jersey (Contract # C-29373) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (Grant # NA-80-FAD-NJBB). 72 p. Haskin, H.H., R.A. Lutz and C.E. Epifanio. 1983. Benthos (Shellfish). Chap. 13. In: The Delaware Estuary: Research as Background for Estuarine Management and Development (Sharp, J.H., Ed.) pp. 183-207. University of Delaware College of Marine Studies and New Jersey Marine Sciences Consortium, Lewes, Delaware. Haskin, H.H., L. A. Stauber, and J. A. Mackin; 1966. Minchinia nelsoni n. sp. (Hapl osporida, Haplosporidiidae) : causative agent of the Delaware Bay oyster epizootic. Science 1 53:l4l4-l4l6. Ingersoll, E. 1881. The oyster industry. Dep. Inter., Wash., D.C., 251 p. Miller, M. E. 1962. The Delaware Oyster Industry, Past and Present. Ph.D. Dissertation, Boston University, Boston, Mass Rolfs, D. H. 1971. Under sail: The dredge boats of Delaware Bay. Wheaton Hist. Soc.,Millville, N.J.,

You might also like

- Assess Your Surroundings!: Do Not Let Others Distract YouDocument2 pagesAssess Your Surroundings!: Do Not Let Others Distract YouEarlNo ratings yet

- Repost of A Well Written Summary of Who James Comey Really IsDocument7 pagesRepost of A Well Written Summary of Who James Comey Really IsEarl100% (1)

- HelloDocument3 pagesHelloEarlNo ratings yet

- Foriegn Election InterfereenceDocument3 pagesForiegn Election InterfereenceEarlNo ratings yet

- Delaware GunfightsDocument10 pagesDelaware GunfightsEarlNo ratings yet

- Aileen Mccabe: Human Development Psy. 127 4W2Document12 pagesAileen Mccabe: Human Development Psy. 127 4W2EarlNo ratings yet

- SB Re Large Capacity MagazineDocument3 pagesSB Re Large Capacity MagazineEarlNo ratings yet

- Truckin' For Trump - Delaware For TrumpDocument1 pageTruckin' For Trump - Delaware For TrumpEarlNo ratings yet

- Situational Awareness in The Workplace An Informational Guide For SecurityDocument5 pagesSituational Awareness in The Workplace An Informational Guide For SecurityEarl100% (1)

- Week 6 Pinky and The BrainDocument3 pagesWeek 6 Pinky and The BrainEarlNo ratings yet

- SB Re Assault Weapons BanDocument9 pagesSB Re Assault Weapons BanEarlNo ratings yet

- An Act To Amend Title 11Document2 pagesAn Act To Amend Title 11EarlNo ratings yet

- SB Re Qualified Purchaser CardsDocument11 pagesSB Re Qualified Purchaser CardsEarlNo ratings yet

- Human Development Psy. 127 4W2 Instructor Aileen Mccabe by Earl R. Lofland AUGUST 30, 2018Document14 pagesHuman Development Psy. 127 4W2 Instructor Aileen Mccabe by Earl R. Lofland AUGUST 30, 2018EarlNo ratings yet

- Gender Dysphoria EditDocument10 pagesGender Dysphoria EditEarlNo ratings yet

- Gender Dysphoria EditDocument10 pagesGender Dysphoria EditEarlNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography For The Delaware Maritime School and Delaware Bay Oyster ProjectDocument9 pagesAnnotated Bibliography For The Delaware Maritime School and Delaware Bay Oyster ProjectEarlNo ratings yet

- Recall On The Grounds of Physical or Mental Lack of Fitness SDocument6 pagesRecall On The Grounds of Physical or Mental Lack of Fitness SEarlNo ratings yet

- Working Thesis Oysters1Document12 pagesWorking Thesis Oysters1EarlNo ratings yet

- Delaware EstuaryDocument15 pagesDelaware EstuaryEarlNo ratings yet

- The Ethical Obligations Regarding Neurological Research Involving Magnetic Resonance Guided Focused UltrasoundDocument7 pagesThe Ethical Obligations Regarding Neurological Research Involving Magnetic Resonance Guided Focused UltrasoundEarlNo ratings yet

- A Bill To Amend Title 16 Delaware CodeDocument2 pagesA Bill To Amend Title 16 Delaware CodeEarlNo ratings yet

- Why Delaware Should Have A Maritime High School.Document17 pagesWhy Delaware Should Have A Maritime High School.EarlNo ratings yet

- Cousteau7 5 16Document12 pagesCousteau7 5 16EarlNo ratings yet

- Aorta Valve Replacement2Document5 pagesAorta Valve Replacement2EarlNo ratings yet

- The Undersea World of Jacques CousteauDocument13 pagesThe Undersea World of Jacques CousteauEarlNo ratings yet

- TRANSCATH Aorta Valve ReplacementsDocument14 pagesTRANSCATH Aorta Valve ReplacementsEarlNo ratings yet

- Amendment19 InspectorGeneralDocument2 pagesAmendment19 InspectorGeneralEarlNo ratings yet

- Maybe A Message Has Been SentDocument4 pagesMaybe A Message Has Been SentEarlNo ratings yet

- State V Richard SivDocument3 pagesState V Richard SivEarlNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Bermad - LisDocument66 pagesBermad - LisRamesh Kumar100% (1)

- Penetron Admix BrochureDocument16 pagesPenetron Admix BrochureTatamulia Bumi Raya MallNo ratings yet

- Lean-Tos, Biv Areas, Campgrounds, and Cabins On FLTDocument3 pagesLean-Tos, Biv Areas, Campgrounds, and Cabins On FLTwaterfellerNo ratings yet

- PipeDocument1 pagePipeJawad ChamsouNo ratings yet

- Wis 4 34 04 PDFDocument16 pagesWis 4 34 04 PDFNitinNo ratings yet

- Corrosion Resistance of Austenitic and Duplex Stainless Steels in EnvironmentsDocument58 pagesCorrosion Resistance of Austenitic and Duplex Stainless Steels in Environmentssajay2010No ratings yet

- Factory Rules 1979 PDFDocument41 pagesFactory Rules 1979 PDFaniktmiNo ratings yet

- Coca ColaDocument25 pagesCoca ColaKush BansalNo ratings yet

- Compendium of Cucurbit DiseasesDocument76 pagesCompendium of Cucurbit DiseasesCurico MysecretgardenNo ratings yet

- Best Rainfall Distribution in UyoDocument10 pagesBest Rainfall Distribution in UyoKadiri ZizitechNo ratings yet

- Project KIDLATDocument7 pagesProject KIDLATLara YabisNo ratings yet

- BC Hydro Letter To FLNRO Chris Addison Re: Amphibian Salvage Permit ExemptionsDocument12 pagesBC Hydro Letter To FLNRO Chris Addison Re: Amphibian Salvage Permit ExemptionsThe NarwhalNo ratings yet

- 8 Comparative Analysisof Produced Water Collectedfrom Different Oil Gathering Centersin KuwaitDocument16 pages8 Comparative Analysisof Produced Water Collectedfrom Different Oil Gathering Centersin KuwaitAlamen GandelaNo ratings yet

- Renderoc PlugDocument3 pagesRenderoc Plugtalatzahoor100% (1)

- Client Project S.O Pipe DrawingDocument5 pagesClient Project S.O Pipe DrawingAgus Umar FaruqNo ratings yet

- PCI Membranes - Wastewater MBR and PolishingDocument14 pagesPCI Membranes - Wastewater MBR and Polishingmansouri.taharNo ratings yet

- SDCA Thesis Stage 1 DeliverablesDocument3 pagesSDCA Thesis Stage 1 DeliverablesAr Aqil KhanNo ratings yet

- Bottle Ecosystem Lab Tim Downs1Document4 pagesBottle Ecosystem Lab Tim Downs1api-259776843No ratings yet

- Grundfosliterature NB NBE NK NKE 60HzDocument20 pagesGrundfosliterature NB NBE NK NKE 60HzCarla RamosNo ratings yet

- Photosynthesis under stress overviewDocument28 pagesPhotosynthesis under stress overviewnaufal samiNo ratings yet

- Natural Gas Storage Engineering: Kashy AminianDocument13 pagesNatural Gas Storage Engineering: Kashy AminianMohamed Abd El-MoniemNo ratings yet

- Geology of KarnatakaDocument36 pagesGeology of KarnatakasayoojNo ratings yet

- Coastal Geotechnical Engineering in Practice, Volume 1Document806 pagesCoastal Geotechnical Engineering in Practice, Volume 1Nguyễn Văn HoạtNo ratings yet

- WBGTDocument12 pagesWBGTNardi 1DideNo ratings yet

- LA River Report CardDocument6 pagesLA River Report CardREC ClaremontNo ratings yet

- Safe Work Method Statement - Part 1: Company DetailsDocument11 pagesSafe Work Method Statement - Part 1: Company DetailsAa YusriantoNo ratings yet

- Readings Upper IntermediateDocument7 pagesReadings Upper Intermediatepiopio123475% (4)

- Solar Energy History All BeganDocument30 pagesSolar Energy History All Beganmar_ouqNo ratings yet

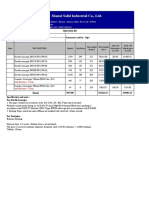

- Decoduct UPVC Conduits & Fittings Manufactured To BS 6099 & BS 4607 and BS EN 50086 / BS EN 61386 Price ListDocument3 pagesDecoduct UPVC Conduits & Fittings Manufactured To BS 6099 & BS 4607 and BS EN 50086 / BS EN 61386 Price ListAly SamirNo ratings yet

- Weather Study Guide Answer KeyDocument4 pagesWeather Study Guide Answer Keyapi-471228436No ratings yet