Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Children Literature

Uploaded by

emysamehOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Children Literature

Uploaded by

emysamehCopyright:

Available Formats

Literacy to Inform and Transform: Empowering Lessons From Childrens Literature

Janelle B. Mathis Leslie Patterson

University of North Texas

No kind of writing lodges itself so deeply in our memory, echoing there for the rest of our lives, as the books we met in our childhood (Zinsser, 1990, p. 3). Students learn literacy lessons every day they walk into classrooms. Each day brings the potential for powerful literacy lessonslessons from teachers, lessons from textbooks and instructional programs, and lessons from trade books. Some of these lessons are intentional, but many are so much a part of the way things work in schools that we may not recognize them as literacy lessons. Too often students are not invited into understandings of literacy that empower them to be proud of themselves or use literacy to change the world. They are immersed in literacy experiences to test and measure their academic achievements or capacities, and inferences based on those data make a powerful difference in how individual students are treated. With the current proliferation of curricular mandates and scripted programs, students may also be surrounded by limited notions of literacy as practiced in the marketplace or workplace and by literacy practices that require rote answers and convergent thinking. In short, current literacy practices in schools can label, stereotype, and set limits on expectations for students; they can impose mainstream culture and values at the expense of students home cultures; and they can constrain divergent thinking and creative problemsolving. Acknowledging that these bureaucratic and cultural literacy practices are inherent to the way todays schools work, many literacy teachers look for ways to demonstrate that literacy can be a source of joy and power to help students experience literacy in a variety of contexts that call for both aesthetic and efferent stances. Those literacy teachers often turn to childrens and young adult literature as a basis for literacy lessons. For those literacy teachers, the question becomes, What can students learn from the literature about the power of literacy to inform and transform? In light of this, we began reexamining childrens books, wondering what demonstrations are provided across the many books that concern reading, writing, and storytelling as central to the plot, theme, or character development. This exploratory study began with a focus on the messages about literacy that lie within the books that might be found in classroom and school libraries. Our initial concern focused on what childrens books might teach students about why people read and write as well as about why literacy is a powerful impetus to inform and transform. That led us to a content analysis of selected childrens literature guided by this question: What messages about literacy are we sending to our readers through childrens and

264

Literacy in Childrens Literature

265

young adult literature? Although this exploration might include more complex notions of what it means to be literate, we chose to focus here only on books that concern reading and writing and the power of story, as these are easily recognized as literacy events by readers.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In our work with teachers and their students, we recognize literacies as multiple and as the processes by which we, as humans, mediate the world for the purpose of learning (Short, Harste, with Burke, 1996, p. 14). People mediate the world by creating sign systems mathematics, art, music, dance, languagethat stand between the world as it is and the world as we perceive it (Short, Harste, with Burke, p.14). For this study, we focus on the sign system of languageon books that concern reading and writing and the power of story, as stated above. Educators readily acknowledge the role of childrens literature as an important aspect of reading instruction as well as models of excellence in writing (Harwayne, 1992; Hickman, Cullinan, & Hepler, 1994). Thematic content analyses from a qualitative perspective have provided powerful explorations of the content of this literature. In a review of research on thematic content analyses, Short (1995) identified four subcategories of issues, including culture (e.g., Cornell, 1993), social issues (e.g., Greenway, 1993), life cycles (e.g., Moore, 1993), and gender (e.g., Rocha & Dowd, 1993). Within each subcategory one would find a variety of themes that touch on literacy issues. For example, Cornell examined traditional rhymes and folktales and found monsters of both language and culture exist in these early literacy lessons. Greenway discovered the many lessons of submission and disempowerment that exist in literature. Moore found unique messages about life in boarding schools in childrens books. And Rocha & Dowd addressed the misrepresentation of Mexican-American females that focuses not only on images that lack gender equity but also on the lack of accurate portrayal of the female within the Mexican culture. Subsequent studies fit within these categories as well as offer insight into literacy and learning (Bushner, 1996; Radencich & Harrison, 1997). Building on a belief in William Zinssers quotation above, we also believe a critical role of literature is nurturing literacy understandings (Gambrell & Amalsi, 1996; Hickman, Cullinan, & Hepler, 1994; Sipe, 1999). Many educators agree with Charlotte Huck (1989) that, We cant achieve literacy and then give children literature; we achieve literacy through literature (as quoted in Sipe, 1999, p. 15). Advocating for literature discussions that invite children to engage in critical meaning making with their peers, Sipe spoke of literatures potential for being an informing and transforming force in childrens lives. Through literature, students begin to realize specifically why and how literacy can empower individuals and groups to bring about social change. Teachers at all grade levels (Crowell, 1993; Foss, 2002; Galda, Shockley, & Pelligrini, 1995) use literature to prompt discussions about society and the need and possibility for change. These teachers point to the ability of children to think critically and sensitively about these issues and the role that books about literacy can play as catalysts to inform and transform. Through literacy we use language (both written and oral) to think about our experiences, to

266

National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53

make sense of written messages, to communicate with others, and to make a difference in our worlds (Mallow & Patterson, 1999). The significance of such a powerful communicative medium also sends us a message that speaks to its own strength for both personal and societal empowerment.

DATA ANALYSIS

The questions guiding our inquiry were: (1) What demonstrations about reading, writing, and story does childrens literature provide? (2) What potential messages does childrens literature send about the purposes of literacy in life? We identified, read, and re-read books of all genres published through 2002 that focused on literacy. To identify these books, we began with an informal search of book review sections of journals published by National Council of Teachers of English, International Reading Association, International Board on Books for Youth, American Library Association, and National Council of Teachers of Social Studies. We then searched according to theme and/or topic in childrens literature resource texts such as Adventuring With Books (McClure & Kristo, 2002), Your Reading (Brown & Stephens, 2003), Books for You (Beers & Lesesne, 2001), and Kaleidescope (Hansen-Krening, Aoki, & Mizokawa, 2003). Additionally, we examined award winning lists such as Notables in Childrens Literature, the International Reading Associations Teachers Choices Awards, Childrens Choices Awards, and Young Adult Choices. Finally, we searched Internet sources using the following descriptors: literacy, reading, writing, and storytelling. The criterion for inclusion was that reading, writing or storytelling was the central focus of the content or theme of the book. We did not include literature in which books, reading, or writing were peripheral to the focus or theme. Additionally, we included only books using language as the foregrounded sign system and not books that focused on the broader notion of multiple literacies. We identified 152 books. As we read each selection, we charted the title, genre, type of literacy being used, the context in which literacy was used, the purpose/function for which it was used, how literacy was defined within this context (reading, writing, or storytelling), and other comments. We do not claim that this is a comprehensive list of such books, but it is a significant sample of the selections that teachers might choose for their classroom libraries. To investigate the first research question (What demonstrations of literacy can be found in childrens and young adult literature?), we used an inductive approach to analysis. We searched for patterns, noting the frequency of certain criteria: literacy form, context of literacy, purpose and function, and definition. As we coded these items, revisiting the original sources (the childrens books) to verify that the context did indeed support a specific function or definition of literacy, key concepts emerged. Hallidays (1982) descriptors of language learning seemed an apt frame for these emerging findings. For example, in these selections, we noted that children might see characters and/or authors learning language, learning about language, and learning through language. Using these three categories as domains, we generated a domain analysis (Spradley, 1980) for further elaboration (See Figure 1). This analysis allowed

Literacy in Childrens Literature

Figure 1 Domain analysis of childrens and young adult literature that offer literacy lessons. About learning to read and/or write Why, for what purpose?

267

To feelenjoy ideas, words, images To connect with family & friends To know myself; self-discovery To proclaim who we are/ To tell our stories/ To express ourselves To function in daily life/To claim power over our daily lives To investigate the world To make the world a better place Adults Children Home School To feel enjoy ideas, words, images To connect with family & friends To know myself; self-discovery To proclaim who we are/To tell our stories/ To express ourselves To function in daily life/To claim power over our daily lives To investigate the world To make the world a better place Adults Children The response to literature The process of research, writing, and publishing Literacy in schools How language works To feel enjoy ideas, words, images To connect with family & friends To know myself; self-discovery To proclaim who we are/ To tell our stories/ To express ourselves To function in daily life/To claim power over our daily lives To investigate the world To make the world a better place Adults Children Letters Diaries/journals Books Poetry Political signs/slogans Newspapers

Who?

Where?

About language, literacy, and literature

Why, for what purpose?

Who?

To learn what?

About using literacy as a tool or a vehicle for a range of purposes

Why, for what purpose?

Who?

How?

268

National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53

us to identify subcategories related to how and why literacy is used in this large and diverse sample of literature. These categories and subcategories guided our inferences about the potential literacy lessons or demonstrations that these books might hold for student readers. We defined those three major categories as follows. Books about Learning Literacy included stories about children and adults learning how to read, write, and tell stories and sometimes focused on the processes of literacy learning, the support that learners needed, or the struggles and triumphs of literacy learning. Books in the category Learning about Literacy included issues related to how literacy began, how language works, how books are made, and how authors write. And books about Learning through Literacy included selections about literacy used as a tool for learning and action, which led to inferences about the purposes of literacy. Because our second research question focused on lessons about the purposes of literacy, we then focused more specifically on the third category, Learning through Literacy, asking specifically, what potential lessons demonstrate why people use reading, writing, and storytelling? This phase of the analysis revealed a set of literacy lessons in the pages of these books. In these books, readers might learn that literacy could be used for these reasons: (a) to feel or to have vicarious experiences; (b) to connect with family and friends; (c) to know ourselves; (d) to proclaim who we are; (e) to tell stories; (f) to function in daily life; (g) to investigate our world; and (h) to make the world a better place. As analysis progressed, our categories became more refined and guided subsequent analysis. More detail on this process is provided in the findings section. Examples of titles within each of the three categories as well as the subcategories of Learning through Literacy can be found in Figure 2.

FINDINGS

Our findings point to numerous books that show characters actively participating in reading, writing, and story-telling events for many purposes. In response to the first research question, we found that only 14 of this 152 book sample (9.2%) focused on characters who were learning to read or write or tell stories. Less than one-fourth (35 books), 23%, contained potential Learning about Literacy demonstrations. Over two-thirds (103 books), 67%, of the books focused on Learning through Literacy, demonstrating a wide range of purposes for reading, writing, and storytelling. In response to the second question regarding potential lessons about the purposes of literacy, we found that many books offer demonstrations of literacy used to connect with other people, to feel or experience (to have fun), to tell stories, to function in daily life, and to investigate the world, but fewer books show literacy used for social change. We were surprised at the small number of books that take a critical stance; that is, few show the use of literacy to oppress or empower or show literacy as the key to economic or political power. This finding is particularly interesting considering our initial concern about the inherent constraints on independent thinking and cultural resistance or creativity within current school literacy practices. A critical stance is grounded in what Freire (Freire & Macedo, 1987) calls concientization, which leads to praxis, or the unity of theory and action in the world. Critical

Literacy in Childrens Literature

Figure 2 Selected titles representing the three categories and the subcategories from initial analysis LEARNING LITERACY

269

Amber on the Mountain, Tony Johnston, NY: Dial, 1994.

Realistic Fiction

When a new family moves into the mountain community, Amber and Anna become best friends. Anna helps Amber learn to read, and when Annas family moves away, back down to the city, Amber teaches herself to write so that she can write letters to her friend. Through moving language and illustrations, this book communicates young Booker T. Washingtons hunger for knowledge and his insight that learning to read and write would lead to a powerful future. Ahmed, a young boy in Cairo, has a secret that he carries with him through the day, as he goes through the city doing his regular chores for his family. When he finally returns home at night, he shares his secret he has learned to write his name! This bookJacks poetry journalchronicles Jacks progress from being a resistant poet Cant write. Brains empty.to his sincere engagement and response to the poems his teacher reads to the class. Through these journal entries, we see Jack beginning to play with language and telling tender stories through poetry.

More Than Anything Else, Marie Bradby, NY: Orchard, Trumpet Books, 1995.

Fictionalized Biography

The Day of Ahmeds Secret, Florence Parry Heide & Judith Heide Gilliland, NY: Scholastic, 1995.

Realistic Fiction

Love That Dog, Sharon Creech, NY: Joanna Cutler, 2001.

Poetry

LEARNING ABOUT LITERACY

What Do Authors Do? Eileen Christelow, NY: Clarion Books, 1995.

Realistic Fiction

This picture book in story board format tells about two authors, next-door neighbors who see the same event and proceed to write two very different books about it. The story takes young readers through the writing process with these two authors. Stevens illustrates how the characters she draws come to life and help tell the story as she makes a book. The funny animal characters look over her shoulder and give her suggestions about what should happen next. Fletcher guides young writers through a process of recording their observations and insights into a Writers Notebook as they become authors.

From Pictures to Words: A Book About Making a Book, Janet Stevens, NY: Holiday House, 1999.

Fantasy

A Writer's Notebook: Unlocking the Writer within You, Ralph Fletcher, HarperTrophy; Reissue, 2003.

Informational

Informational My Very Own Library Treasure fantasy Hunt, Candace J. Jackson, Richard D. Greenwood, Thousand Oaks, CA: Museum Mania, 1998.

A treasure hunt, this book gives children an interactive way to get acquainted with their public libraries with the help of a caterpillar and a butterfly.

270

National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53

Figure 2, con't. Selected titles representing the three categories and the subcategories from initial analysis LEARNING THROUGH LITERACY Literacy for . . . Learning to "feel" through literary experiencesto imagine, to create

BOOK, George Ella Lyon, New York: DK Publishing, 1998.

Realistic Fiction

The illustrations and word images in this book communicate the wonder, the joy, and the excitement of reading, of meeting the author within the pages of the book. Tomas moves with his family to work in the fields. One summer he finds a cool place and friend in the library. His grandfather encourages him to read and to share stories with his family just the grandfather has always done.

Toms and the Library Lady Pat Mora, NY: Dragonfly Books, Alfred A Knopf, 2000.

Poetry

Literacy for . . . Learning to connect with family and friends

The Hickory Chair, Lisa Rowe Fraustino, NY: Arthur A. Levine, 2001.

Realistic Fiction

Blind since birth, Louis loves his grandmother, who leaves a handwritten note to each family member before she dies. Years later, Louis finds his note hidden in the hickory chair his grandmother rocked him in as a child. Kenyons grandmother is the Keeper of the stories, ready to pass those stories down to a female member of the family. But Kenyon decides to buy a baseball glove instead of a birthday gift for his grandmother. He feels so guilty that he makes a book of her stories to give her, and she decides that he should become the Keeper of the stories for the next generation.

Keepers, Jeri Hanel Watts & Felicia Marshall, NY: Lee & Low, 1997.

Realistic Fiction

Literacy for . . . Learning to know ourselves Realistic Fiction A long-time favorite, this book tells the story of Leigh, who writes to his favorite author and receives a surprise in return. This is really a story of a young boy learning to deal with lifes challenges. Precious Jones, a teenager caught in horrible circumstances, meets a teacher and a family of classmates who help her build a hopeful future. Her journal and her poetry reflect her growing sense of self and her increasing control over her life. This book is for mature teens because of the difficult situations the characters face.

Dear Mr. Henshaw, Beverly Cleary, NY: Dell, 1983.

Realistic Fiction

PUSH, Sapphire, NY: Vintage Books, 1997.

Literacy in Childrens Literature

271

Figure 2, con't. Selected titles representing the three categories and the subcategories from initial analysis LEARNING THROUGH LITERACY Literacy for . . . Learning to proclaim who we are/ to tell our stories

My Diary from Here to There/ Mi Diario De Aqui Hasta Alla, Amada Irma Perez, Childrens Book Press, 2002.

Realistic Fiction

As her family emigrates to the U.S. from Mexico, Amanda writes about her sadness and her fears in her journal. Through these stories and memories, she realizes that she is stronger than she thought, and that her connections with her Mexico home are also strong. The title character tells her story of her familys immigration to the states, settling into a new classroom, and the story of why the family made the move. Her paintings tell her stories until she learns the English words to communicate with her new friends.

Marianthes Story, Painted Words and Spoken Memories, Aliki, NY: Greenwillow Books, 1998.

Realistic Fiction

Literacy for . . . Learning to function in daily life

Oh, How I Wished I Could Read!, John Gile, JGC, 1995.

Realistic Fiction

The main character, a little boy who cannot (yet) read, has a series of mishaps that could have been avoided if he could readlike wet paint signs. This little novel highlights the exploits of two middle schoolers who are best friends. One wants to write a book; the other takes that on as a challenge. By writing letters, submitting the manuscript, and negotiating other details of the publishing world, they do succeed.

The School Story, Andrew Clements, NY: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers. 2001.

Realistic Fiction

Literacy for . . . Learning to investigate our world

Archibald Frisby, Michael Chesworth, NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1994.

Fantasy

Archibald Frisby is a clever boy who loves science. His mother wants him to take a break from his investigations so she sends him to summer camp. However, he continues his inquiries at camp. Harriet is a very observant young girl whose journal is a constant companion. Her writing that journal gets her in trouble with her friends and she learns to balance her investigations and journalistic efforts with her relationships with friends and family.

Harriet the Spy, Louise Fitzgerald, NY: HarperTrophy, 1964.

Realistic Fiction

Literacy for . . . Learning to make the world a better place

The Color of My Words, Lynn Joseph, NY: HarperCollins, 2001. Freedom School, Yes, Amy Littlesugar, NY: Philomel, 2001.

Realistic fiction (chapter)

Political uprisings provide a place for a young girl to use her voice and writing talents in the Dominican Republic. A 19 year old is determined to begin a school for African Americans in the South to learn to read of their rich heritage in spite of racist threats.

Historical fiction (picture)

272

National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53

theorists and educators seem to agree that the foundation for such praxis is a willingness and ability to read the world, or to assign meanings to our perceptions of the worldmeanings that take social, economic, and political systems into account, meanings that ask not only why things are as they seem but also who stands to benefit. As we contemplated the literacy messages related to social action, we looked again at the literary selections that might hold lessons about literacy as a tool or vehicle for this kind of reading. We realized that our initial categories needed further refinement, particularly the category of Learning Through Literacy. Within the books in this category, we saw that each text seemed to deal with a particular level of a social/cultural system: self, friends and family, and the larger world/society (see figure 3). Of course, these systems overlap and are nested one inside another, but we can focus on any one of these three system levels as a way to more carefully explore these literacy lessons made available in books. Reframing our second research question about the purposes of literacy embedded in childrens literature, we asked, What potential lessons do these books offer about why and how we can use literacy within the three systems within which we live our lives: Ourselves? Our transactions with family and friends? Our place in the larger world? A closer look at these selections suggested that, across these three system levels, characters used literacy for three primary purposes: to find out what they need to know (inquiry), to speak out (voice), and to do what must be done (action). Our analysis suggests that these categories overlap. They are most

Figure 3

Potential literacy lessons for inquiry, voice and action in three nested systems: self; family and friends; and the larger world

SELF Inquiry For self discovery Voice To proclaim who we are Action Transform ourselves

FRIENDS AND FAMILY Inquiry Explore cultural and family identities Voice To claim power; to tell our stories Action To take social action at home, school, and neighborhood

LARGER NATURAL OR SOCIAL SYSTEMS Inquiry To investigate the world Voice To make public statements about what is & what should be Action To take action to make the world more just or self-sustaining

Literacy in Childrens Literature

273

useful as heuristics for consideration of the literature and are not distinct, mutually exclusive categories for data analysis. For example, we could argue that the boy in S, Se Puede!, Yes, We Can! Janitor Strike in L.A. (Cohn, 2002), while developing his personal literacy in school, is also supporting his mothers role in the custodians strike and, thus, taking action in the larger world. The following explanations provide examples from childrens literature to illustrate each of these categories. These examples of inquiry, voice, and action demonstrations are meant to be suggestive of a wide range of possibilities. Literacy for Inquiry Self. Many of these books offered lessons about literacy as a tool for exploration, inquiry, and investigation into issues related to self-knowledge, identity creation, and transformation. In Trinos Choice (Bertrand, 1999), Trino is talking with a visiting poet, Montoyo, who asks Trino if he can read. In response to Trinos, Of course, I can read, Montoyo replies, No, man. Do you know how to read? Not just figure out letters and sounds, but get into the words and figure out what theyre saying to you. Can you read like that? Trinos answer elicits a powerful response from Montoyo: It matters when a guy asks you to sign a paper and suddenly hes hauling you off to jail. It matters when a lady asks you to sign something and next thing you knew, your kids going to be raised as some other mans son. If you cant read, man, peoplell tell you what you ought to think and that you cant do more than scrub toilets the rest of your life. Thats why it matters, man. Montoya rolled the white books between his handsIll tell you something no one ever said to me son. If you can be smart about reading, nobodyll ever take whats yours out of your hands cause youll know more than they do. Youll know how to protect what you love most. (pp. 46-47) These are powerful words and significant knowledge for a young man at the point in his life where he must make decisions that forever will affect his future. We owe our children opportunities to become literate in the sense demonstrated herewhat Harste and Leland (2000) described as having the power to elect a stance that allows him or her to avoid becoming a victim (p. 67). Family and friends. Other selections offered lessons about literacy as a tool for inquiry into issues about family and friends. A familiar example is Toms and the Library Lady by Pat Mora, illustrated by Raul Colon (2000). Toms and his family follow the crops, moving each season to work in the fields. One summer he finds a cool place in the city library and finds a friend in the librarian. His grandfather encourages him to read and to bring the books home to read stories to the familiesstories in print to add to the stories that his grandfather has always told. Toms enables his whole family to imagine worlds beyond their current experience and enriches their family time through these stories in the library books he brings home. World/society. Several books focused on using literacy for inquiry into larger issues about the natural world or social realities. For example, Archibald Frisby (Chesworth, 1994) is a clever boy who loves science. His mother thinks he spends too much time doing science. Wanting him to take a break from his investigations, she sends him to summer camp. Archibald, however, does not stop his investigation and inventing just because he is at camp. With his

274

National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53

knowledge of physics and the natural world, he leads fellow campers to consider larger issues and complexities of the natural world within which the camp functions. Rather than a focus here on the personal issues of friends and family, Archibalds concern is that of the larger world and making others more universally aware. Literacy for Voice Second, a number of books focused on literacy and voice, using literacy to make a place for ourselves and to participate in various discourse communities. This theme also can be seen at each of the three system levels. Self. The books showed characters using literacy to proclaim themselves and tell the world who they are. An example that children might find particularly relevant to their personal experience is Marianthes Story: Painted Words and Spoken Memories (Aliki, 1998). Marianthe tells her story of her familys immigration to the states, why the family made the move, and how Marianthe settles into her new classroom. The format of the book demonstrates the complexity of our interconnected stories. We can first read Marianthes story of her homeland, and then, turning the book over, we can read of her experiences in the new school from the other cover. Both stories demonstrate how she uses her paintings to tell her stories until she learns the English words to communicate with her new friends. Family and friends. Some books showed characters using literacy to tell family and cultural storiesto proclaim who we are as a family or as a group of people. Keepers by Jeri Hanel Watts and Felicia Marshall (1997) demonstrated this use of voice. Kenyons grandmother is the Keeper of the stories, and, according to family tradition, is preparing to pass those stories down to a female member of the family who will become the new Keeper. Kenyon spends much of the book searching for a worthy gift for his grandmothers birthday and finally decides to make a book of her stories to give her. In turn, she decides that Kenyon should become the Keeper of the stories for the next generation. World/society. At this level, a few of the books showed characters speaking up, in sometimes courageous ways, to write about things as they are or as they should be. A powerful example of voice in the larger world is found in When My Name Was Keoko (2002) by Linda Parks. This story takes place in northern Korea during World War II at a time when the Japanese had taken over this part of Korea and were attempting to eliminate the culture and language of those living there. Told through the eyes of a young girl and her brother, the reader becomes aware of the role of literacy in trying to keep culture alive and preserve their voice. An underground newspaper, a journal kept by Keoko, and their realization of the importance of their Korean names when given Japanese names all speak to this notion of having voice. One chapter ends with: If the Japanese lost the war, Uncle could come home. If they lost, Abuji could be principal of his own school. We could learn Korean history. We could use our real names again. And Abuji could teach me the Korean alphabet. How could an alphabetletters that didnt even mean anything by themselvesbe important?

Literacy in Childrens Literature But it was important. Our stories, our names, our alphabet. Even Uncles newspaper. It was all about words. If words werent important, they wouldnt try so hard to take them away. (p. 107)

275

In keeping with the words of Ann Berthoff in the Forward to Literacy, Reading the Word and the World (Freire & Macedo, 1987), Language is the means to a critical consciousness, which, in turn, is the means of conceiving of change and of making choices to bring about further transformationsLiberation comes only when people reclaim their language and, with it, the power of envisagement, the imagination of a different world to be brought into being (p. xv). Literacy for Action Third, we saw that some of these selections focused on literacy as a tool for action. Self. Some of the books showed characters using literacy in a struggle to make changes in themselves or to transform who they are in their worlds. A particularly sobering example is PUSH by Sapphire (1997). Precious Jones is a teenager caught in devastating circumstances, including learning to live with HIV, a second pregnancy by her father, and her expulsion from school. In an alternative school, Precious meets a teacher and a family of classmates who help her build a hopeful future. Her journal and her poetry reflect her growing sense of self and her increasing control over her life. This book is for mature teens because of the difficult situations the characters face. Family and friends. Other selections focused on characters using literacy to make changes in family, school, or neighborhood situations. The School Story by Andrew Clements (2001) highlights the exploits of two middle schoolers who are best friends. One wants to write a book; the other takes on that challenge and becomes the chief agent and publicist. By writing letters, submitting the manuscript, and negotiating other details of the publishing world, they succeed in getting the book published. Although not completely believable, this book offers a demonstration of how young people can use literacy skills to influence the people around them. World/society. Finally, we saw selections in which characters used literacy to make social and political changes. S, Se Puede! Yes We Can! Janitor Strike in L.A. (Cohn, 2002), mentioned earlier, is a picture book depicting the janitor strikes in California. A young child is shown making signs to do his part in helping his mother and other workers improve working conditions and pay for custodians. The next day Miss Lopez took some of the kids from my class on the bus to downtown Los Angeles. When Mama saw us, she was so happy she almost cried. As we marched, I held my sign as high as I could.On the sidewalk, people rooted for all of us marchers on the street. There were thousands and thousands of people all around me! I held on tight to Miss Lopez hand. Carlos, she said, this is a celebration of courage. After three long weeks, the strike was over. My mama and the janitors finally got the respect and the pay raises they deserved.

276

National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53 Carlitos, Mama said, I couldnt have done it without you. She hung the sign I made on our living room wall. Its the most beautiful sign in the world, she said. (unpaged)

In Freire and Macedos (1987) words, Reading the world always preceded reading the word, and reading the word implies continually reading the world.Reading the word is not preceded merely by reading the world, but by a certain form of writing or rewriting it, that is, of transforming it by means of conscious, practical work (p. 35).

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Here, we summarize our findings related to our two research questions. First, this analysis of childrens and young adult literature suggests that teachers have access to a wide range of quality literature that can provide students with rich and diverse demonstrations of how and why people use reading, writing, and storytelling. Even in classrooms where teachers and students feel the constraints imposed by high stakes assessment systems and mandated instructional materials, teachers can fill their classroom libraries with books about literacy. They can make time and space for students to learn about authentic literacy by giving students access to books that offer lessons about the power of literacy. Second, we find a great deal of variety in the demonstrations of literacy embodied in these books, including a range of genres: realistic fiction, historical fiction, informational books, biography, fantasy, and poetry. In addition, we see these characters reading and writing in a variety of forms: letters, diaries, journals, books, newspapers, political signs, slogans, and poetry. Third, we found in this sample many demonstrations of literacy as a way to build relationships and connect with family and friends. Students reading these books would learn that reading, writing, and storytelling help us feel more a part of our families, our cultural groups, our communities. They would learn that stories and letters make strong links across time and distance and can strengthen relationships with those we love. They would learn that literacy is a cultural practiceone of those practices that help us build and rebuild our multiple identities. Fourth, although books concerning literacy lessons about making the world a better place are not numerous, we did find excellent examples for classroom use. Teachers who take a critical stance not only try to teach students that literacy can build individual power but that literacy can also be a tool for social and political change. These teachers can find books that offer compelling demonstrations of actual people and fictional characters who use reading, writing, and storytelling to change their worlds. Sometimes these lessons are subtle, and teachers will want to use the books as springboards to more complete discussions about the challenges and potentials for working to make significant changes. Fifth, as we examined the books that demonstrated the use of literacy to change the world, we found it useful to envision change in three systems: self, friends and family, and larger social and natural worlds. Within each of those systems, we noticed that books foregrounded one of three purposes: inquiry, voice, and action. In other words, these books showed that literacy could be used for inquiry, for speaking out, and for taking action in our individual or personal

Literacy in Childrens Literature

277

growth, among our families and friends, and in the larger world. These categories promise a useful way to talk with teachers and with students about how people can use literacy to change their worlds. For example, we found numerous books that focus on reading, writing, and storytelling as a means to personal power or voice. Working with disengaged students is arguably the most significant challenge facing literacy teachers, and these books can be used as springboards for writing or for discussion about how to use reading, writing, and storytelling to proclaim ourselves and to speak our minds. Some students would respond to books that demonstrate that voice is about proclaiming who we are (self). Some students would respond to the use of voice to make a place for ourselves within our family or among our friends. Some students would be intrigued by books that show characters using their voices to make a difference in the larger world. These books are a promising resource for teachers who work with disengaged or passive students, and these categories give us a way to think about our choice of books to engage particular students.

IMPLICATIONS AND SIGNIFICANCE

Implications for practice are clear. First, teachers who want to demonstrate that literacy can lead to personal empowerment and social action can choose from a range of childrens and young adult literature. They may still face challenges like finding the time for students to read and respond to these texts, but thoughtful and courageous teachers will make the time, and they can find a range of resources in these books. Second, the conversations and engagements around these resources greatly influence the literacy lessons that are learned. It is not just about the texts; it is also about the transactions students and teachers have with the texts and with one another. The professional literature offers an array of instructional ideas about how to engage students in these literacy transactions, but an obvious implication from this study is the development of thematic text sets related to the power of literacy (Mathis, 2002; Short, 1995). Such text sets would make it possible for students to explore the power of literacy as represented across multiple genre, perspectives, and knowledge systems. Third, the categories in Figures 1 and 3 offer a scheme for teachers to think about the purposes and power of literacy. Finally, these titles offer the opportunity to expand students notions about literacy beyond academic school contexts to literacy situations outside classroom walls. Future research should include classroom-based investigations, including teacher research, to document how teachers and students read and respond to these and other texts that hold potential lessons about the power of literacy. Future research should also include both deeper analyses and critiques of the texts listed here, as well as wider inquiry into texts other than bookspotential lessons about literacy in newspapers, magazines, poetry, drama, the Internet, cinema, song lyrics, etc. This analysis suggests that current books represent a relatively limited range of ethnic perspectives on learning literacy, learning about literacy, and learning through literacy. Future research should seek more cross-cultural examples and make crosscultural comparisons of potential literacy lessons. A theoretical implication became clear as we read and re-read these books. Researchers and teachers cannot talk about what literacy lessons will necessarily be learned from these books. Given a transactional stance toward comprehension and response to literature, we can

278

National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53

only speak of potential lessons. Teachers cannot control what lessons their students will learn about the power of literacy from reading these books; they can only provide access and encouragement to engage in those transactions. This implication, of course, refers back to our original assumption that literacy is meaning-makinga meaning-making potential across knowledge systems and sign systems (Short, Harste, with Burke, 1996). For this reason, throughout this discussion, we have referred to potential literacy lessons, rather than implying that the meanings are inherent in the books themselves. Perhaps our most significant insight from this investigation is that, given the potential for alternative literacy lessons in some of these books, we should not assume that curricular mandates and scripted programs necessarily limit students notions of literacy to rote answers and convergent thinking. Teachers and students have the creative power to construct new realities; to talk back to the bureaucracy with alternative messages about the power of literacy. We are reminded that oppressive and limiting literacy texts and demonstrations (for example, high stakes tests and scripted instructional programs) merely hold a potential for meaning-making. Teachers can influence these potential literacy lessons through their choices of texts and their literacy transactions and demonstrations. Even in an oppressive learning environment, teachers can make the space for potentially empowering literacy lessons. The books identified in this study can help teachers do that. As literacy educators we are constantly reminded of the different perceptions of literacy that learners have for academic school contexts and real life situations. We strive to bridge these differences, despite political pressures, with authentic experiences that connect our classrooms to home communities. Auerbach (1991), as quoted in Cadiero-Kaplan (2002), argued that there can be no disinterested, objective, and value-free definition of literacy: The way literacy is viewed and taught is always and inevitably ideological (p. 71). The literature a teacher makes available to students reflects what is valued about reading, writing, and oral language. Teachers understandings of the power and purposes for literacy will influence the literacy lessons learned. It follows that using these books in preservice and in-service experiences will provide both personal experiences for teachers as literacy learners and will provide a knowledge of these titles for instructional decisions. To conclude, we return to Huck (1989) who suggested, We cant achieve literacy and then give children literature; we achieve literacy through literature (as quoted in Sipe, 1999, p. 15). That is as true for teacher educators, researchers, and teachers as it is for young learners. We began this investigation with a concern that political and economic initiatives have cast simplistic and inauthentic roles on school literacy learning. Our initial objective was to explore texts that broaden and deepen simplistic yet widely espoused notions about literacy and that show literacy empowering people and promoting social change. Through this investigation, we realized that informed book choices can address each of these concerns. Reading these books, however, also deepened our own notions about literacy as a complex and empowering process. We learned about particular books that can help teachers bring powerful literacy demonstrations to classroom settings, but more important, we learned that these books can help all of us outgrow our current selves (Rowe, Harste, & Short, 1988, p. 9). These are books that can inform us and transform our understandings about the power and complexity of literacy.

Literacy in Childrens Literature

279

REFERENCES

Aliki. (1998). Marianthes story: Painted words and spoken memories. New York: Greenwillow. Auerbach, E. (1991). Literacy and ideology. In W. Grabe (Ed.), Annual review of applied linguistics (pp. 71-85). New York: Cambridge University Press. Beers, K. and Lesesne, T., (Eds.). (2001). Books for you, an annotated booklist for senior high (14th ed.). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Bertrand, D. G. (1999). Trinos choice. Houston, TX: Arte Publico Press. Brown, J. E. & Stephens E.C., (Eds.). (2003). Your reading, an annotated booklist for middle school and junior high (11th ed.). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Bushner, D. E. (1996). A look at how books, reading, or writing are portrayed in childrens literature published from 1990 through 1995. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York. Cadiero-Kaplan, K. (2002). Literacy ideologies: Critically engaging the language arts curriculum. Language Arts, 79, 372-381. Chesworth, M. (1994). Archibald Frisby. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Clements, A. (2001). The school story. New York: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers. Cohn, D. (2002). S, Se puede! Yes, we can! Janitor Strike in L.A. El Paso, TX: Cinco Puntos Press. Cornell, C. E. (1993). Language and culture monsters that lurk in our traditional rhymes and folktales. Young Children, 48(6), 40-46. Crowell, C. G. (1993). Living through war vicariously with literature. In Patterson, L., Santa, C. M., Short, K. G., & Smith, K. (Eds.). Teachers are researchers: Reflection and action (pp. 51-59), Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Foss, A. (2002). Peeling the onion: Teaching critical literacy with students of privilege. Language Arts, 79, 393-403. Freire, P. & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy, reading the word and the world. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey. Galda, L., Shockley, B., & Pelligrini, A. D. (1995). Sharing lives: Reading, writing, talking, and living in a first grade classroom. Language Arts, 72, 334-339. Gambrell, L. B. & Almasi, J. F. (Eds.). (1996). Lively discussions! Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Greenway, B. (1993). Creeping like a snail unwillingly to school: Negative images of school in childrens literature. The New Advocate, 6, 105-114. Halliday, M. A. K. (1982). Three aspects of childrens language development: Learning language, learning through language, and learning about language. In Y.Goodman, M. Huassle, & D. S. Strickland (Eds.), Oral and written language development research: Impact on the schools (pp.7-19). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Hansen-Krening, N., Aoki, E., and Mizokawa D. T., (Eds.). (2003). Kaleidoscope, a multicultural booklist for grades K-8 (4th ed.). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Harste, J. & Leland, C. (2000). The discus thrower: The reading of literature as metaphor for curricular reform. The New Advocate, 13, 61-69. Harwayne, S. (1992). Lasting impressions: Weaving literature into the writing workshop. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Hickman, J. Cullinan, B. E., & Hepler, S. (Eds.). (1994). Childrens literature in the classroom: Extending Charlottes web. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon. Mallow, F. & Patterson, L. (1999). Framing literacy: Teaching/learning in K-8 classrooms. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon. Mathis, J. (2002). Multicultural text sets: Organizing for critical thinking. The New Review of Childrens Literature and Librarianship, 55-69. McClure, A. A. and Kristo, J. V. (Eds.). (2002). Adventuring with books, a booklist for Pre-K-grade 6 (13th ed.). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Moore, R. C. (1993). Boarding school books: A unique literary opportunity. Journal of Youth Services in Libraries, 6, 378-386. Mora, P. (2000). Toms and the library lady. New York: Dragonfly Books, Alfred A Knopf. Parks, L. S. (2002). When my name was Keoko. New York: Clarion.

280

National Reading Conference Yearbook, 53

Radencich, M. C. & Harrison, M. (1997). Images of principals in childrens and young adult literature. The New Advocate, 10, 335-48. Rocha, O. J. & Dowd, F. S. (1993). Are Mexican-American females portrayed realistically in fiction for grades K-3?: A content analysis. Multicultural Review, 2(4), 60-70. Rowe, D. W., Harste, J. C., & Short, K. G. (1988). The authoring cycle: A theoretical and practical overview. In J. Harste, K. G. Short, with C. Burke (Eds.), Creating classroooms for authors. (pp. 337). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Sapphire, (1997). PUSH. New York: Vintage Books. Short, (Ed.). (1995). Research & professional resources in childrens literature: piecing a patchwork quilt. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Short, K. G., Harste, J., with Burke, C. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Sipe, L. (1999). Childrens literature, literacy, and literary understanding. Journal of Childrens Literature, 23(2), 6-17. Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant observation. Fort Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart, Winston. Watts, J. H. & Marshall, F. (1997). Keepers. New York: Lee & Low Books. Zinsser, W. (Ed.). (1990). Worlds of childhood: The art and craft of writing for children. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

You might also like

- Pedagogy of The OppressedDocument3 pagesPedagogy of The Oppressedchristiane_05100% (4)

- Gender Bias and Stereotypes in Young Adult LiteratureDocument53 pagesGender Bias and Stereotypes in Young Adult LiteratureAlice Mia Merdy100% (1)

- Grammar and Vocabulary Test for Unit 1Document3 pagesGrammar and Vocabulary Test for Unit 1sara82% (33)

- Final Written Unit 5Document7 pagesFinal Written Unit 5Math4 studyNo ratings yet

- Identity Construction in Young FictionDocument12 pagesIdentity Construction in Young Fictioncamila_valenzuela_64No ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Philosophical Thoughts On EducationDocument15 pagesChapter 1: Philosophical Thoughts On EducationEdivon Mission100% (2)

- Grammar and Vocabulary TestDocument4 pagesGrammar and Vocabulary Testemysameh100% (2)

- Cumulative Skills Test Units 1-5 Test ADocument5 pagesCumulative Skills Test Units 1-5 Test AemysamehNo ratings yet

- Liberating Praxis - Paulo Freire's Legacy For Radical Education and PoliticsDocument47 pagesLiberating Praxis - Paulo Freire's Legacy For Radical Education and PoliticsGiorgio Bertini50% (2)

- Pedagogy, Oppression and Transformation in A Post-Critical Climate The Return To Freirean Thinking Andrew OShea, Maeve OBrien 2011Document193 pagesPedagogy, Oppression and Transformation in A Post-Critical Climate The Return To Freirean Thinking Andrew OShea, Maeve OBrien 2011Mark Malone100% (4)

- Teaching Diversity and Tolerance in The ClassroomDocument16 pagesTeaching Diversity and Tolerance in The ClassroomNicolle AndreaNo ratings yet

- Five Models of Curriculum PlanningDocument12 pagesFive Models of Curriculum PlanningSol100% (1)

- Social Studies in the Storytelling Classroom: Exploring Our Cultural Voices and PerspectivesFrom EverandSocial Studies in the Storytelling Classroom: Exploring Our Cultural Voices and PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- Critical Pedagogy SyllabusDocument9 pagesCritical Pedagogy SyllabusRubenNo ratings yet

- Literature Circles: A Collaborative Reading/Writing ActivityDocument6 pagesLiterature Circles: A Collaborative Reading/Writing ActivityDewi UmbarNo ratings yet

- Educational Value of Childrens LiteratureDocument22 pagesEducational Value of Childrens LiteratureSharmila PingaleNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Teaching English Literature to ChildrenDocument56 pagesThe Importance of Teaching English Literature to ChildrenHector PetersenNo ratings yet

- Reading Freire and HabermasDocument224 pagesReading Freire and HabermasAna Carmen Palhares FerreiraNo ratings yet

- The Roles of Literature in Language Teaching ClassroomDocument5 pagesThe Roles of Literature in Language Teaching ClassroomPierro De ChivatozNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Thoughts On EducationDocument30 pagesPhilosophical Thoughts On EducationCharyl Louise MonderondoNo ratings yet

- 5 Paulo - Freire - A - Critical - Encounter - (2 - EDUCATION - IS - POLITICS - PAULO - FREIRE'S - CRITICAL - PEDAGOGY - )Document12 pages5 Paulo - Freire - A - Critical - Encounter - (2 - EDUCATION - IS - POLITICS - PAULO - FREIRE'S - CRITICAL - PEDAGOGY - )Мария РыжковаNo ratings yet

- Module 1: Philosophical Thoughts On Education: Unit I: Educational FoundationDocument9 pagesModule 1: Philosophical Thoughts On Education: Unit I: Educational FoundationSc JuanicoNo ratings yet

- Multiculture LiteratureDocument36 pagesMulticulture LiteratureSue ManafNo ratings yet

- Children LitDocument56 pagesChildren LitJay VaronaNo ratings yet

- The Teacher and The Community, School Culture and Organizational LeadershipDocument18 pagesThe Teacher and The Community, School Culture and Organizational LeadershipJefril Mae PoNo ratings yet

- Reading Paulo Freire - His Life and Work PDFDocument244 pagesReading Paulo Freire - His Life and Work PDFSteve Sahuleka100% (2)

- Vocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test BDocument5 pagesVocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test Bemysameh50% (4)

- Vocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test ADocument5 pagesVocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test Aemysameh100% (5)

- Table of Content and Academic WritingDocument5 pagesTable of Content and Academic WritingYorutsuki LuniaNo ratings yet

- Guiding Response Young To Students Response To LiteratureDocument8 pagesGuiding Response Young To Students Response To LiteratureLindsay BrelsfordNo ratings yet

- Comber 1997 Critical LiteraciesDocument18 pagesComber 1997 Critical LiteraciesElirene IrenNo ratings yet

- 6020 PaperDocument6 pages6020 Paperapi-310321083No ratings yet

- Authentic Literacy Duke-Science-Rt 60 4 41Document12 pagesAuthentic Literacy Duke-Science-Rt 60 4 41api-264543623No ratings yet

- Educ 606 Revised Change PughDocument7 pagesEduc 606 Revised Change Pughapi-605891707No ratings yet

- 9780203125311_previewpdfDocument45 pages9780203125311_previewpdfVincentius KrigeNo ratings yet

- HeablerDocument5 pagesHeablerMaria Ronalyn Deguinion AcangNo ratings yet

- How African American Families Respond to Culturally Relevant Children's LiteratureDocument17 pagesHow African American Families Respond to Culturally Relevant Children's LiteratureVisal SasidharanNo ratings yet

- Research Article 2Document21 pagesResearch Article 2api-371673914No ratings yet

- Educ 606-Revised Inquiry Essay Yifang XuDocument7 pagesEduc 606-Revised Inquiry Essay Yifang Xuapi-608917974No ratings yet

- Making Connections Across Literature and Life: Kathy G. ShortDocument19 pagesMaking Connections Across Literature and Life: Kathy G. ShortRoy Jhones Balingkit AbsinNo ratings yet

- Opening Up Spaces For Early Critical PDFDocument13 pagesOpening Up Spaces For Early Critical PDFjiyaskitchenNo ratings yet

- module3ENG ChuDocument5 pagesmodule3ENG ChuLaurence DuqueNo ratings yet

- UNIT 1 Children and Ado LitDocument11 pagesUNIT 1 Children and Ado LitMayraniel RuizolNo ratings yet

- The Elementary Bubble Project: Exploring Critical Media Literacy in A Fourth-Grade ClassroomDocument11 pagesThe Elementary Bubble Project: Exploring Critical Media Literacy in A Fourth-Grade Classroomapi-246737973No ratings yet

- Ls 540 01 - Essay 1Document8 pagesLs 540 01 - Essay 1api-289742240No ratings yet

- Using Children's Literature ToDocument24 pagesUsing Children's Literature ToMichaelaNo ratings yet

- Literatura para MeninosDocument13 pagesLiteratura para MeninosCarla dos Santos FigueiredoNo ratings yet

- Psa 2Document2 pagesPsa 2api-262115146No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - ENG 120 HandoutsDocument7 pagesChapter 2 - ENG 120 HandoutsCarl JohnNo ratings yet

- Reading For CharacterDocument9 pagesReading For CharacterVelentina Rizki SutariNo ratings yet

- Beyond "Is This OK?": High School Writers Building Understandings of GenreDocument10 pagesBeyond "Is This OK?": High School Writers Building Understandings of Genreapi-297629759No ratings yet

- Literacy and Social JusticeDocument9 pagesLiteracy and Social Justiceapi-274597520No ratings yet

- Interdisciplinalty EssayDocument5 pagesInterdisciplinalty Essayapi-598689165No ratings yet

- Awareness, Managing Emotions, Handling Anxiety, Motivating Themselves and Being Sensitive Towards OthersDocument2 pagesAwareness, Managing Emotions, Handling Anxiety, Motivating Themselves and Being Sensitive Towards OthersJulienneNo ratings yet

- Professional Reading 3Document1 pageProfessional Reading 3api-421137169No ratings yet

- El Ed 122 Pedagogical Implications LectureDocument5 pagesEl Ed 122 Pedagogical Implications Lecturemtkho1909No ratings yet

- A Letter To Teachers Is A Multiple Chapter Book Manifesto of What Perrone Considers ImportantDocument13 pagesA Letter To Teachers Is A Multiple Chapter Book Manifesto of What Perrone Considers Importantapi-516988940No ratings yet

- YokotaJ Learning Through Literature PDFDocument8 pagesYokotaJ Learning Through Literature PDFYSNo ratings yet

- SSHRC Program of StudyDocument7 pagesSSHRC Program of Studyapi-396348596No ratings yet

- Social Studies FinalDocument6 pagesSocial Studies Finalapi-519224747No ratings yet

- Through The Sliding Glass DoorsDocument10 pagesThrough The Sliding Glass DoorsLuis Fernando Rodriguez AriasNo ratings yet

- Annoted BibliographyDocument12 pagesAnnoted Bibliographyapi-341418874No ratings yet

- Pedagogical Implications for Teaching LiteratureDocument10 pagesPedagogical Implications for Teaching LiteratureLarie CanoNo ratings yet

- Litelature in Language Teaching: Dr. I Ketut Warta, MsDocument7 pagesLitelature in Language Teaching: Dr. I Ketut Warta, MsAria SupendiNo ratings yet

- Schools Can Play An Important Role in AdolescentsDocument2 pagesSchools Can Play An Important Role in Adolescentsshe laNo ratings yet

- MMSD Classroom Action Research Vol. 2010 Adolescent Literacy InterventionsDocument28 pagesMMSD Classroom Action Research Vol. 2010 Adolescent Literacy InterventionsAulia DhichadherNo ratings yet

- Ya Lit Research PaperDocument12 pagesYa Lit Research Paperapi-557418832No ratings yet

- Books With Potential For Character Education and A Literacy RichDocument15 pagesBooks With Potential For Character Education and A Literacy Richchoirul anamNo ratings yet

- Improving Reading Attitudes of College StudentsDocument9 pagesImproving Reading Attitudes of College StudentsMarelie GarciaNo ratings yet

- Edla430 Assignment 3 - Unit of WorkDocument35 pagesEdla430 Assignment 3 - Unit of Workapi-319193686No ratings yet

- 3 Little PigsDocument13 pages3 Little PigsjiyaskitchenNo ratings yet

- Education ReadingsDocument4 pagesEducation Readingskarimindustries1No ratings yet

- Analytic ReadingDocument24 pagesAnalytic Readingbersam05No ratings yet

- Interdisciplinarity Essay GuoDocument6 pagesInterdisciplinarity Essay Guoapi-609103971No ratings yet

- Literacy Across The Curriculum PaperDocument13 pagesLiteracy Across The Curriculum Paperapi-300009409No ratings yet

- Greenwalt, Ladson-Billlings, Freud, DerridaDocument20 pagesGreenwalt, Ladson-Billlings, Freud, DerridaKyle GreenwaltNo ratings yet

- The Disciplined MindDocument28 pagesThe Disciplined MindGabriela CumebaNo ratings yet

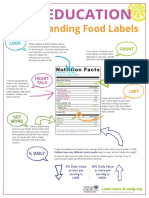

- Nutrition LabelDocument2 pagesNutrition LabelemysamehNo ratings yet

- Using Wikis To Develop Writing Performance Among PDFDocument9 pagesUsing Wikis To Develop Writing Performance Among PDFemysamehNo ratings yet

- 1840-Article Text-5281-1-10-20150122Document11 pages1840-Article Text-5281-1-10-20150122emysamehNo ratings yet

- New ENGLISH PLACEMENT SAMPLE QUESTIONS PDFDocument4 pagesNew ENGLISH PLACEMENT SAMPLE QUESTIONS PDFIsaac CordovaNo ratings yet

- Question Tags - Test: A - Which Sentences Are Correct?Document3 pagesQuestion Tags - Test: A - Which Sentences Are Correct?mimisiraNo ratings yet

- Authorizing Readers Resistance and Respect in Teaching Literary Reading ComprehensionDocument2 pagesAuthorizing Readers Resistance and Respect in Teaching Literary Reading ComprehensionemysamehNo ratings yet

- Label ReadingDocument4 pagesLabel ReadingemysamehNo ratings yet

- Test - Infotech English For Computer Users Work Book - Unit 4 - QuizletDocument4 pagesTest - Infotech English For Computer Users Work Book - Unit 4 - QuizletemysamehNo ratings yet

- Nutrition BookDocument5 pagesNutrition Bookemysameh100% (1)

- Relationship Between Narrative and EngagementDocument54 pagesRelationship Between Narrative and EngagementemysamehNo ratings yet

- Engagement Inventory Teacher RecordDocument1 pageEngagement Inventory Teacher Recordapi-369324244No ratings yet

- Revision Exercises Relative ClausesDocument3 pagesRevision Exercises Relative ClausesemysamehNo ratings yet

- Understanding nutrition labels and daily valuesDocument2 pagesUnderstanding nutrition labels and daily valuesemysamehNo ratings yet

- Norman Holland Willing Suspension of DisbeliefDocument12 pagesNorman Holland Willing Suspension of DisbeliefemysamehNo ratings yet

- Advances in Language and Literary Studies: Article InfoDocument5 pagesAdvances in Language and Literary Studies: Article Infosave tony stark from spaceNo ratings yet

- Using Narrative Distance To Invite Transformative Learning ExperiencesDocument18 pagesUsing Narrative Distance To Invite Transformative Learning ExperiencesemysamehNo ratings yet

- Using Narrative Distance To Invite Transformative Learning ExperiencesDocument18 pagesUsing Narrative Distance To Invite Transformative Learning ExperiencesemysamehNo ratings yet

- Cumulative Vocabulary & Grammar Test Units 1-5 Test A PDFDocument3 pagesCumulative Vocabulary & Grammar Test Units 1-5 Test A PDFMarija SazoņenkoNo ratings yet

- Unit 23 I Wish - If Only PDFDocument11 pagesUnit 23 I Wish - If Only PDFAnais Espinosa MartinezNo ratings yet

- Cumulative Skills Test Units 1–5 Test B Skills ReviewDocument5 pagesCumulative Skills Test Units 1–5 Test B Skills ReviewemysamehNo ratings yet

- Enlivening The Classroom Some Activities For Motivating Students inDocument10 pagesEnlivening The Classroom Some Activities For Motivating Students inemysamehNo ratings yet

- Bringing Poetry in Language Classes Can Make LanguageDocument5 pagesBringing Poetry in Language Classes Can Make LanguageemysamehNo ratings yet

- An Investigation On Approaches Used To Teach Literature in The ESL ClassroomDocument7 pagesAn Investigation On Approaches Used To Teach Literature in The ESL ClassroomOthman Najib100% (1)

- The Power of LiteratureDocument12 pagesThe Power of LiteratureDana HuţanuNo ratings yet

- 41 - YILDIZ - GENCAn Investigation On Strategies of Reading in First and Second LanguagesDocument9 pages41 - YILDIZ - GENCAn Investigation On Strategies of Reading in First and Second LanguagesemysamehNo ratings yet

- Paulo Freire and Ivan Illich's views on education and technologyDocument10 pagesPaulo Freire and Ivan Illich's views on education and technologyn pNo ratings yet

- We Make The Road by WalkingDocument292 pagesWe Make The Road by WalkingmattyankoNo ratings yet

- Teacher Chapter 1 Organizational LeadershipDocument9 pagesTeacher Chapter 1 Organizational Leadershipreamarie sevillaNo ratings yet

- A Constructivist Appraisal of Paulo Freire's Critique of Banking System of EducationDocument13 pagesA Constructivist Appraisal of Paulo Freire's Critique of Banking System of Educationvikash dabypersadNo ratings yet

- Acuna Rodolfo Introduction To Occupied America PDFDocument3 pagesAcuna Rodolfo Introduction To Occupied America PDFShatabdiDasNo ratings yet

- A Decade of Critical Information Literacy ReviewDocument21 pagesA Decade of Critical Information Literacy ReviewMagiPegiNo ratings yet

- IereDocument4 pagesIereJuliana Shawa NsouliNo ratings yet

- What Is PedagogyDocument4 pagesWhat Is PedagogyLionil muaNo ratings yet

- Abrahams - Changing Voices, Voices of Change & Collins - Creating A Culture For Teenagers To Sing in HSDocument28 pagesAbrahams - Changing Voices, Voices of Change & Collins - Creating A Culture For Teenagers To Sing in HSEmily LescatreNo ratings yet

- Hawai'i Journeys in Nonviolence: Autobiographical Reflections, Edited by Glenn D. Paige, Lou Ann Ha'aheo Guanson and George SimsonDocument162 pagesHawai'i Journeys in Nonviolence: Autobiographical Reflections, Edited by Glenn D. Paige, Lou Ann Ha'aheo Guanson and George SimsonCenter for Global NonkillingNo ratings yet

- Social Justice Requires Decolonizing PedagogyDocument12 pagesSocial Justice Requires Decolonizing PedagogyPepaSilvaNo ratings yet

- Anti-Oppression Perspective PaperDocument19 pagesAnti-Oppression Perspective Paperapi-546034011No ratings yet

- 8611 Assignment 2Document16 pages8611 Assignment 2Majid KhanNo ratings yet

- Communitas: Old French LatinDocument6 pagesCommunitas: Old French LatinJustine Carl CasayuranNo ratings yet

- Prodromou - English As Cultural ActionDocument11 pagesProdromou - English As Cultural ActionJorge Gonza0% (1)

- Critical PedagogyDocument90 pagesCritical PedagogyPrince JoaquinNo ratings yet

- Ci 702 Personal Thoery of CurriculumDocument13 pagesCi 702 Personal Thoery of Curriculumapi-295217564No ratings yet