Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Evolution of The Palestinian Refugee Camps in Jordan. Between Logics of Exclusion and Integration

Uploaded by

ohoudOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Evolution of The Palestinian Refugee Camps in Jordan. Between Logics of Exclusion and Integration

Uploaded by

ohoudCopyright:

Available Formats

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini...

- Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

Collections lectroniques

de lIfpo

Livres en ligne des Presses de lInstitut franais du Proche-Orient

Villes, pratiques urbaines et construction nationale en Jordanie

- Myriam Ababsa and Rami Daher

Deuxime partie. Politiques urbaines et disparits sociales / Second Part. Urban Politics and Social Disparities

The Evolution of the Palestinian

Refugee Camps in Jordan.

Between Logics of Exclusion and

Integration

Lvolution des camps de rfugis palestiniens en Jordanie. Entre logiques dexclusion et dintgration

JALAL AL-HUSSEINI

p. 181-204

Abstract

Lvolution des camps de rfugis palestiniens en Jordanie. Entre logiques dexclusion et

dintgration

Bien quils nabritent que 20 % des rfugis palestiniens, les dix camps de rfugis officiels grs

conjointement par lUNRWA et la Jordanie sont le symbole officiel de la volont des rfugis de

prserver leur droit au retour . Mais ces espaces urbains trs denses sont aussi perus, de faon

plus ngative, comme des foyers dopposition islamiste et de marginalisation socioconomique

dont lexistence menace potentiellement les efforts mis en uvre par les autorits jordaniennes

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 1 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

afin de moderniser le pays.

Larticle analyse la manire dont la Jordanie et lUNRWA ont gr, travers lvolution de leur

administration des camps, les diffrentes dimensions symboliques lies la question des rfugis.

Ce faisant, il souligne limpact de leurs politiques sur les rapports quont entretenus les camps et

leurs habitants avec leur entourage immdiat travers les dcennies en termes dintgration ou

dexclusion. La spcificit politique des camps en tant quespaces dans lattente dun retour aux

foyers originels a impos llaboration de directives urbanistiques dexception (hors des plans

municipaux des villes de Jordanie) destines maintenir leur aspect temporaire et, partant, leur

signification politique particulire. Aucun plan durbanisation des camps ne fut jamais dvelopp.

Ce sont leurs habitants qui, sans grande assistance, entreprirent dtendre horizontalement les

units dhabitation initiales. Cela explique laspect anarchique des camps, labsence despaces

rcratifs ainsi que lexigut de leurs ruelles.

Ce mode de gouvernance semi-informel, d en partie la sensibilit politique de toute

intervention dans les camps ( sanctuaires du droit au retour) a t mis en cause par la

conclusion dun accord de paix avec Isral en 1994 et lchec du processus de paix isralopalestinien ds 2000. La volont subsquente des autorits jordaniennes de modernisation du

pays en dpit de labsence dun accord sur la question des rfugis a conduit les autorits

jordaniennes intgrer les camps des programmes nationaux de rhabilitation des quartiers

dfavoriss. Ce dveloppement, qui se conjugue une diminution des services humanitaires de

lUNRWA, laisse prsager une marginalisation politique des camps dont la reprsentation risque

de ne plus se formuler quen termes de lieux de pauvret et de dclassement social.

Full text

1

Jordan hosts ten official refugee camps, namely camps that are managed jointly by

local authorities and UNRWA1. This article analyzes the evolution of their physical and

housing infrastructure against the background of the countrys socioeconomic and

political development and within the context of the Arab-Israeli conflict/peace process.

How relevant is it to analyze refugee realities through the prism of a host countrys

internal policies? Six decades after their exodus, the Palestinian refugees spread across the

Middle East (about 90% of the Palestinian refugees worldwide) remain generally defined

as temporary stateless exiles vying for their return to their homes in historic Palestine.

Their situation in Jordan differs somewhat from this general picture. Unlike the other

Arab host countries that have kept Palestinian refugees stateless, Jordan has granted them

formal citizenship without denying their right of return. In 1949, the refugee population

under Jordanian sovereignty amounted to about 70,000 in (Trans)Jordan and 280,000 in

the West Bank. Citizenship was also conferred on the 462,000 indigenous West Bankers

(DE BEL-AIR, 2003: 83). The Palestinian refugees thus became fully fledged Jordanian

citizens, endowed with the same rights and duties as any native Jordanian citizen, pending

the day when they would be given the opportunity to choose between repatriation to

Palestine or permanent settlement in Jordan or elsewhere.2 This unique citizen/refugee

status has placed them within a web of formal and informal balancing mechanisms of

inclusion/exclusion meant to guarantee their integration within Jordans society while

preserving their right of return.

Although they are presently home to less than one fifth of the total refugee population

living in Jordan, namely 338,000 out of 1.9 million refugees (UNRWA, 2009),3 the

refugee camps epitomize the dilemma pertaining to the refugees dual

Palestinian/Jordanian identity. Generally viewed as the most vivid markers of the

refugees and Jordans unified commitment to the right of return, they are simultaneously

portrayed either as hubs of potential political dissent or as places of social marginalization

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 2 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

that affect the countrys drive towards liberal modernization.

This article explores this dilemma through the analysis of the camp management

policies pursued by national and international stakeholders since the early 1950s.

Following a first historical section that investigates the origins of the camps in Jordan and

tackles their representations within the Jordanian society at large, the article goes on

highlighting the political and socioeconomic stakes involved in the development of camps

physical and housing infrastructure. In so doing, it sheds a new light on the right of

return. A rallying slogan across the Palestinian society and the Arab world as a whole,4

the right of return has also constituted an operational norm that has deeply influenced

the camps evolution patterns as well as Jordans urban landscape.

A) The evolving significance of the

Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan

1) The terms of the refugee camps establishment

5

Plots of land placed by the host government at the disposal of the League of the Red

Cross/Crescent societies (LRCS - 1949-1950) and of UNRWA (from May 1950 onwards),

the refugee camps were designed to accommodate those scattered groups of destitute

refugees, mostly jobless farmers and labourers who had not been able to afford any decent

lodging.5 Their transfer from the caves, mosques and various types of informal habitat to

well-organized camps made it possible to improve the channelling of humanitarian relief

and trim operational costs. It also enabled the local authorities and UNRWA to better

control a potentially destabilizing population primarily characterized by its attachment to

Palestine. In March 1949, refugees residing in Jordans first camps (in Zarqa, Irbid,

Sukhneh and Shuneh) made up 21% of the total registered refugee population, a

percentage similar to the current proportion of refugees living in camps (18%) (LRCS: 38).

In order to facilitate the transportation of goods and services, the camps were

established near the Kingdoms cities and towns and/or with rapid access to main roads

(RAMZOUN, 2001: 252-3; DPA, 2004: 23). Four of Jordans current official camps were set

up in the years that followed the Palestinian exodus of 1948: the Zarqa camp in 1949; the

Irbid camp in 1950; Ammans al-Hussein camp in 1952 and Amman New Camp (Wihdat

camp) in 1955. Six other camps, labelled emergency camps, were set up in the wake of

the 1967 Arab-Israeli war to accommodate homeless displaced Palestinians, be they first

time displaced or second time displaced 1948 refugees : the Talbiyeh camp in the

Amman governorate, the Marqa camp (also known as the Hitteen or the Schneller

camp) in the Zarqa governorate; the Baqaa camp in the Balqa governorate, the Jerash and

Souf camps in the Jerash governorate, and the Husn (or Azm al-Mufti) camp in the Irbid

governorate.6

Unlike most refugee camps across the world, Palestinian refugee camps were not

designed to separate their inhabitants from the host population or to provide them with a

different legal status from non-camp refugees. Quite the opposite, UNRWAs initial

mandate, as defined by resolution 302 (IV) of the UN General Assembly in December

1949, provided for the rapid integration of the refugees within the local and regional

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 3 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

labour markets through the gradual replacement of relief assistance (food rations, medical

care and primary education) by a program of public works involving terracing,

afforestation, irrigation schemes and road construction. Camp refugees were the first

targets of UNRWAs integration policy. Their re-housing in Jordans towns and villages

and the camps dismantlement were expected to follow suit.

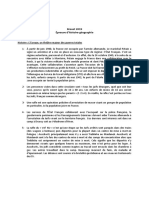

Zoom Original (jpeg, 356k)Source : UNRWA (http://www.un.org/unrwa/refugees/

jordan.html)

2) Evolving contexts, lasting representations

8

The persistence of the camps across the Near East thus reflects UNRWAs and to a

lesser extent the host authorities- failure to resolve the socioeconomic aspect of the

Palestinian refugee issue. The key factor here is the refugees staunch opposition to any

project likely to jeopardize their right of return. And as UNRWA put it in 1955, the strong

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 4 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

10

11

12

9/5/12 9:28 AM

desire of the refugees to return to their homeland also influenced the policies of Near East

governments in this matter.7 The refugee camps have since then embodied the

humanitarian and political plight borne by the palestinian refugees. They have also been

portrayed as the guardians of a preserved intrinsic Palestinian-ness in exile (FARAH, R.

1997); the ultimate custodians of the right of return; or, as a UN official recently put it

after a visit to the Irbid camp in 2008, the real face of Palestine outside Palestine.8

Other representations triggered by the rise of Palestinian nationalism amongst refugee

communities since the late 1960s have stressed the political challenges the camps have

posed to the the countrys social and political stability. Independent republics

encroaching on Jordans sovereignty during the heydays of the Palestinian resistance in

the late 1960s (SALIBI, 1993: 230; MASSAD, 2001: 238-246), the camps have also been

portrayed by other sources as places of relative political estrangement, whose

inhabitants are little concerned by Jordanian politics. As a matter of fact, little campaign

activity was recorded before national elections and turnouts in such elections have been

low since 1989 (RAJFUS, M., 1990; AL-SIJILL, November 2007). Morevoer, the communitybased organizations leadership in the camps is elected primarily on the candidates

allegiance to Palestinian factions (Fatah for instance) or Jordanian parties sympathetic to

them, typically the Jordanian Islamic Action Front vis--vis Hamas.9

However, since the Black September events of 1970, the refugee camps have remained

relatively calm. In the early 2000s, demonstrations did take place in support of the

Intifada al Aksa and Jordans normalization policy with Israel. But since September 2001,

when scores of people were arrested for holding unauthorized rallies in the Baqaa refugee

camp, virtually no demonstrations have taken place in the camps and there have been few

breaches to this ban.10

From a socioeconomic perspective, the stigma of poverty and destitution that initially

characterized the camps has lingered on despite their gradual socioeconomic integration

within their surrounding environment. This representation is supported by numerous

surveys that indicate that camp refugee households are on average poorer than non-camp

refugees or than the Jordanian population as a whole.11 This and the allegedly more

conservative (backward) attitudes of the camp refugees have contributed to maintain

them in relative social confinement. Such a phenomenon has also been observed in the

other host countries and even within the sister native populations of the West Bank and

the Gaza Strip (SHAMIR, 1980; AWAD, 2008). Poverty, social confinement and political

estrangement have led some observers to question the allegiance of the camp refugees to

the Jordanian polity, as is emblematically demonstrated in S. al-Khazendars book on

Jordan and the Palestinian question. Tackling their status as the most underprivileged

[enduring] low standard of living, education and employment, who still contribute to the

strength of any opposition, whether it be the Islamist movement, the leftist parties, or the

PLO, this author denies them the label of Jordanians of Palestinian origin (ALKHAZENDAR, 1997: 35-36).

In recent years, the Jordanian authorities have sought to counter these divisive

stances by developing a unifying narrative underpinning the authorities reform agenda

under the names of Jordan first, the National Agenda and We are all Jordan. In this

context, the camp refugees status as fully-fledged citizens has been repeatedly confirmed

through public statements stressing they were part and parcel of the Jordanian people

with the same rights and duties as any other Jordanians12 and as a dear part of Jordan

that should be given the same attention and services as other parts of the country such as

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 5 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

the countryside and the semi-desert areas.13

B) Who runs the camps? The

institutional management of

temporariness

13

The governments rallying statements also reflect a new approach to the management of

the camps social and physical infrastructure. Centred on the power sharing between

UNRWA and the governmental authorities involved in such management, the following

analysis highlights its operational and political underpinnings as well as its influence on

the future of the refugee issue in Jordan.

1) UNRWA the extent and limits of non territorial

jurisdiction

a) UNRWA as a key stakeholder in the camps

14

15

Since its establishment in December 1949, the Agency has seen its temporary mandate

extended by the UN General Assembly on a three (sometimes five) year basis.14 Although

camp refugees have always constituted a minority of the total number of registered

refugees across the Near East, UNRWA has generally been viewed as inseparable from the

camps it services in its fields of activity. This may be explained by the political significance

the refugees and host authorities have ascribed to both UNRWA and the camps as key

markers of the refugee issue.15 Operational considerations are also to be taken into

account. While the Agencys facilities cover nearly all strong refugee concentrations inside

and outside camps,16 only camps host the full range of UNRWA elementary and

preparatory schools, health clinics, relief distribution and social centres. Dependency on

UNRWA services has for that matter been comparatively stronger among camp dwellers.

In the field of education for example, 85% of camp children attended the Agencys primary

schools compared to 36% of non-camp refugee children during the school year 20042005.17 UNRWAs operational significance in the camps is also reflected in the additional

responsibilities it bears there, such as garbage collection and the maintenance and

rehabilitation of shelters. Outside camps, these tasks fall under the responsibility of the

municipalities. The Agencys quasi-municipal presence in the camps is illustrated by the

concentration of blue UN flags that adorn its facilities and, more concretely, by the

presence of an UNRWA Camp Services Officer officially responsible for the overall

management of the Agencys facilities, the updating of the camp refugees family records,

and the channelling of their requests and concerns to UNRWAs central administration

(i.e. the Jordan Field Office).

The wide range of responsibilities taken on by UNRWA in the camps, together with the

international dimension of its UN mandate, have contributed to conferring to the Agency

the informal status of an alien governmental body holding extra-territorial sway over

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 6 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

the camp communities. Historically, this particular representation originates from the

early decades of its existence, when camp refugees were fully dependent on the Agencys

relief services. The control the Agency exerted through its Camp Services Officer (more

appropriately entitled camp director in Arabic) on the camp population was drastic: he

would decide whether to accept new refugee families in the camp and regularly verify the

camp inhabitants status as bona fide refugees according to strict eligibility rules.18 He also

checked any improvements the refugees brought to their shelters to verify their conformity

to the housing regulations devised by UNRWA and the host authorities. Conceived to

maintain the shelters temporary character, these regulations initially prevented the

construction of a first floor, except in exceptional circumstances.

b) The decline of UNRWAs influence

16

17

18

19

20

In the 1970s, the Agencys control over camp matters, in Jordan and elsewhere, started

to decline, which led its Headquarters to redefine its role as a mere service provider. As

illustrated by the statements of its Commissioner-General in 1972:

[A]n emphasis on UNRWA camps and on relief, while correctly conveying an

impression of the refugees displacement from their traditional homes and of their

continuing need for help, has also contributed to certain misconceptions. UNRWA

provides services in rather than administers camps [] the camps are not extraterritorial areas under United Nations jurisdiction (UNRWA, 1972: parag.2; 1975:

parag.22).

The decline of UNRWAs influence stems from various factors. Mounting budget

constraints compelled the Agency to gradually reduce its services, delay acquisition of

educational and medical equipment and put a ceiling on the recruitment of additional

employees.19 Lack of resources combined with demographic growth and restrictions on

camp expansion (see below) led to a deterioration of its social infrastructure.20

Overworked, its staff also lost the capacity and authority required to enforce housingrelated regulations.

The decline of UNRWAs influence in the camps is also due to more positive

developments. As early as the 1960s, a younger, more educated, generation of camp

refugees managed to access the local and the Middle Eastern job markets (especially the

Gulf countries). They left the camps, thus reducing their material dependence on

UNRWA.21 But those refugees who remained in the camps, including the newcomers

replacing those who had moved out - see below section 2.b) also started to show signs of

empowerment, engaging in self-help activities for the improvement of their shelters as

well as the camps amenities.22 In some camps, committees, such as the residents

association set up in the Wihdat camp in 1969, were created in order to channel more

efficiently the camps needs to the stakeholders and to undertake various communitybased activities. UNRWA has promoted and supported these initiatives, even pushing the

various community-based organizations it once created, such as the Women Program

centres and the Community rehabilitation centres for disabled, to operate

autonomously.23

Present opinions about UNRWAs role and performance are rather mixed. While the

Agency has kept its aura as the embodiment of the international communitys

commitment in favour of the refugees humanitarian and political rights, criticisms against

its inability to sustain its mandate have mushroomed in refugee circles and among

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 7 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

Jordanian officials. Reminding the international community that the decrease in its

humanitarian services strained the countrys finances and created social problems, the

government has repeatedly made it clear that Jordan should not be expected to take over

UNRWAs activities or normalize the camps: the latters symbolic power as guardians of

the refugees cause is at stake.24

2) The rise of the host authorities as territorial

institutions

a) The mixed legacy of integrated extra-territoriality

21

22

Initially, the governmental authorities role in the camps was mainly limited to

maintaining law and order and assisting UNRWA in carrying out its humanitarian

mission.25 Because they were to remain temporary places vested with the symbolism of the

right of return, camps were subsequently left aside from Jordans urban development

policies at national and municipal levels. Camp refugees themselves also opposed any

infrastructural improvement that could be interpreted as an acceptance of permanent

resettlement outside Palestine. It thus took UNRWA and the host authorities ten full years

(1951-1961), and countless numbers of persuasion campaigns, to replace tents with more

durable shelters made of more permanent materials such as mud, concrete, stone, iron,

zinc and asbestos (UNRWA, 1961). These housing units have nevertheless kept their initial

label shelter (mawa, malja) and were not called homes (bayt, dar). In the same vein,

the camps are still named moukhayyam (i.e. tent camp). Moreover, in the first decade of

their existence, the early camps shelters were not connected to municipal services: toilets

were public, drinking water was provided in distribution centres, and there was no

sewerage system. It is only in the early-mid 1960s that the sprawling municipalities

started integrating the camps within their public services systems. It is also during this

period that some of the main alleys were asphalted (DESTREMAU, 1994: 93-94). Today, the

camps remain excluded from the municipalities development plans, but almost all of their

shelters are connected to municipal services. In urban areas, their inhabitants pay taxes to

the adjoining municipalities for the use of water, electricity and telephone lines.26

Exclusion from local development plans has entailed a lack of decent urban planning.

UNRWA and the host authorities actually elaborated specific regulations designed to

maintain the camps temporary character. These regulations concerned the camps

boundaries, which were considered non-extendable for fear that any extension might lead

to the camps incorporation with neighbouring areas. They also dealt with the use of land

plots and shelters. Camp refugees were initially allotted plots of land not exceeding 80100 square meters per household, which included a shelter comprising one 12 square

meter room for a family of 4-5 members; or two rooms for families of 6-8 persons.27 While

refugees were in principle allowed to construct additional rooms beside the original core

shelter in order to accommodate new family members, any vertical extension of the

shelters was prohibited. Finally, camp inhabitants were not entitled to ownership - or

rental - rights to the plot of land, or to use the shelters for commercial purposes. The

status of most camp land as private land rented by the authorities for a period of 99 years

also explains such restrictions.28

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 8 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

23

24

9/5/12 9:28 AM

Over time, however, the expansion of the camps population (due to natural

demographic growth and to the arrival of newcomers as from the mid-1950s) challenged

these temporary regulations. The figures are striking, indicating a multi-fold increase in

the camps population over the decades. In Amman for instance, the al-Hussein and

Wihdat camps, which initially sheltered 8,000 and 9,500 refugees, currently house about

30,000 and 50,000 inhabitants, respectively.29 However, neither UNRWA nor the host

authorities have ever endorsed the responsibility for developing a sound urban

management policy in the camps. The host authorities implicitly laid the onus on

UNRWA, which is responsible for building shelters and handing them over to the

Palestinian refugees.30 Conversely, the Agency has stigmatized the host countries

neglect. In its own words: The host governments have not enforced adherence to urban

planning and architectural guidelines in camps nor have they brought camp infrastructure

to standards adhered to in non-camp areas. UNRWA has no mandate for and cannot

enforce such adherence (UNRWA, 2004).

The demographic explosion of the refugee population, combined with the existing camp

regulations, has had two consequences. First, density and rates of overcrowding have

attained extremely high levels, sparking acute social problems and substandard

environmental conditions. UNRWA figures indicate that density in the camps varies from

70,000 to 103,000 persons/sq. km in the early 1950s camps; and from 34,000 to 69,000

persons/sq. km in the post-1967 emergency camps (see table at the end of this article).

In comparison, the overpopulated cities of Mumbai and Kolkata in India claim fewer than

30,000 persons per sq.km.31 Overcrowding figures in the camps shelters are also

impressive. About 58 percent of camp households endure overcrowding in terms of room

occupancy (over two persons per room) as opposed to 38% of refugee households living

outside camps32. According to living condition surveys carried out in Jordan in the early

2000s, overcrowding increases the incidence and transmission of respiratory diseases,

forces children and young adults onto the streets, sparks domestic violence and provides

children with a poor study environment, thus causing problems of school dropout and

illiteracy (KHAWAJA, TILTNES, 2002: 128-130). Second, the refugees unguided adaptation to

the expansion of their households has resulted in the narrowing of pathways, the virtual

absence of recreational areas and unsatisfactory environmental conditions in terms of

ventilation, sunlight, humidity, temperature, storage, and privacy.33 As horizontal space

was soon exhausted, refugees started to expand their shelters vertically, benefitting from

or taking advantage of-UNRWAs leniency or inability to control the situation.

b) The Jordanian authorities flexible governance of the

refugee camps

25

Jordans current involvement in refugee camp management far exceeds that of any of

the other host countries. This may be due to the citizen status of most camp refugees. As

early as 1975, it took over from a financially-stricken UNRWA in the task of controlling the

expansion of shelters. It also took direct charge of the maintenance and the rehabilitation

of the camps housing and physical infrastructure comprising water, sewerage, electricity

and road networks. These are responsibilities endorsed by UNRWA in the other host

countries. Ultimately, as the Jordanian officials have publicly admitted, they have come to

accomplish for humanitarian reasons- what UNRWA cannot do or what exceeds its

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 9 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

26

27

28

9/5/12 9:28 AM

financial capability (DPA: 2004: 77).

Although camp refugees (except the Gazan displaced persons) are entitled to

participate in national and local elections, the camps municipal affairs have been run alongside UNRWA - by specific governmental agencies.34 Established in 1988 following

King Husseins decision to disengage Jordan from the West Bank, the Department of

Palestinian affairs (DPA) focuses solely on the camps located in Jordan proper.35 The

extensive mandate falling upon the DPA in the camps has lent it such impressive labels as

a state in the state (Destremau, B; 1995: 21), a label that once blessed UNRWA. Its

duties include assistance to UNRWA and non-governmental bodies operating in the

camps,36 the monitoring of refugees usage of the shelter units, the registration of

commercial ventures and the rehabilitation of the physical infrastructure (DPA, 2004: 1314).37 Based in Amman, with regional offices, its leverage in the camps is secured through

camp services committees. Responsible for the channelling of the refugees claims and

the implementation of community projects, these committees are, unlike the 1960s

residents associations, almost governmental bodies composed of 7-13 members (not

necessarily camp dwellers) whose budgets, operations and membership are monitored by

the DPA. The committees lack of autonomy has at times emerged as a bone of contention

with the refugee communities. These communities, supported by members of parliament,

have repeatedly demanded that the committees membership be elected by the camps

inhabitants, not imposed upon them. But to no avail: the Jordanian authorities have been

unwilling to support any initiative likely to encourage political factionalism at a time when

they are striving to promote national unity.38

Yet, the DPAs management of the camps infrastructure may be described as relatively

flexible. It has sought to adapt the housing regulations to the refugees evolving needs.

Thus, the construction of an additional floor above the initial shelter for residential

purposes is now permitted upon authorization by its services; commercial buildings may

even add two floors provided the extension does not exceed 6 metres.39 Probably on

account of the political sensitivity related to camp matters, the DPA has generally not

taken legal action in order to pull down illegal constructions, unless public safety was at

risk. Rather, it has endeavoured to prevent such illegal initiatives through persuasion and

pre-emptive measures (DESTREMAU, 1994: 97). This relatively liberal attitude has

accelerated the urbanization of camps located within large city boundaries. The examples

of the Wihdat and the al-Hussein camps in Amman are telling. Most shelters have two

floors (i.e. one floor on top of the original shelter) and the number of commercial

buildings with three floors has mushroomed. Besides the traditional small and family

businesses (grocers and jewellers for instance), new commercial ventures comprising

banks, electronics shops, taxi agencies, fast food outlets and pharmacies have opened in

the past two decades, turning these camps into relatively affluent commercial areas

(HAMARNEH, 2002: 180-181; JABER, 2002: 252-56). In contrast, refugee camps located

outside the cities have been deprived of such developments. For instance, the Talbiyeh

camp, which lies about 30 km south of Amman, still appears mired in poverty with few

work opportunities.

Another example of governmental flexibility pertains to land transactions. Despite the

camps temporary status, the refugees have developed a sense of ownership towards their

shelters. This was first reflected, as seen above, in the extensions and upgrades they

brought to them. Then, in the 1960s, those refugees seeking and able to afford more

comfortable housing outside camps started renting out or selling their shelters to

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 10 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

newcomers in need of extra-space or impoverished non-camp refugees, including

returnees from Kuwait and other Gulf countries in the early 1990s.40 Such transactions,

also involving commercial ventures, have become such a regular feature of the camps

dynamics that the informal transaction acts (hujjas) are recorded in real estate offices

located within the camps themselves (AL-HAMARNEH, 2002: 182). Over time, the urban

camps inclusion within the citys booming real estate market and commercial activities

has resulted in the increase in the actual value of the land. The Wihdat camp, for instance,

has seen the value of its shelters increase dramatically, from an average of JD 3,000 in

1970 to around JD 19,000 in 2007.41

c) The impact of the peace process with Israel

29

30

Jordans Wadi Araba treaty with Israel in 1994 announced a further increase of its

involvement in camp affairs. Titled Refugees and Displaced Persons, article 8 recognized

the massive human problems caused to both Parties by the conflict in the Middle East

(par.1) and recommended their alleviation, notably through the implementation of

agreed United Nations Programs and other agreed International economic programs

concerning refugees and displaced persons, including assistance to their settlement

(par.2.c). In the following years, and for the first time ever, Jordan unilaterally included

the refugee camps in a national development program aimed at upgrading living

conditions in the countrys impoverished areas (also covering informal squatter areas and

remote villages). Named the Economic and Social Productivity Program (ESPP), this

program tackled the refugee camps infrastructural conditions through two sub-programs:

first, the Community Infrastructure Program (CIP) that aimed at upgrading the camps

physical infrastructure in terms of water supply, sewerage and drainage systems, roads

and footpaths, pedestrian crossings at major roads, street lighting and retaining walls42;

second, the Housing Projects for the Poor (HPP) scheme, which has aimed at upgrading

deteriorated shelters inhabited by poor refugees.43 The novelty of these interventions also

resides in the involvement in their design and implementation of a governmental agency

that had so far been alien to camp matters; the Housing and Urban Development

Cooperation (HUDC).44

Equally remarkable is the relatively positive response the HUDC interventions elicited

amongst refugees. This confirmed the view that, several decades after the 1948 and the

1967 exoduses, Palestinian refugees and displaced people were favourable to the notion of

durable upgrading in the camps provided this did not affect their temporary status. Yet,

some observers, including members of opposition parties, have contended that such a

trend inevitably induced the refugees permanent resettlement in Jordan45 and led to the

gradual disappearance of the camps through their transformation into poor housing

neighbourhoods.46 It may be too early to jump to such conclusions. The Jordanian

authorities made it clear from the outset that the ESPP programs would remain ad hoc

interventions that would not affect the camps temporary character and political

symbolism (AL-DALY, 1999). The camps political significance actually affected the

modalities of the interventions, drastically restricting their scope: unlike interventions

outside camps, the social infrastructure, mainly under UNRWA supervision, was left

untouched; no demolition of shelters occurred; and the rehabilitation of the most

dilapidated of them was limited to a single room and/or kitchen and bathroom. Most

importantly, no solutions could be brought to the camps most crucial problems, namely

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 11 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

high demographic densities and overcrowding. Finally, even though the HUDC kept a

leading role, the DPA was not sidelined. It continued to play a significant role by

participating in and/or approving the design criteria of the interventions, and took part in

their implementation as well as in their follow-up (AL-DALY, 1999; DPA, 2004: 83-85).47

Ultimately, the camps overall status has not changed. In the recent words of the Greater

Amman Municipality :

Although these camps are now permanent and well-established communities

within Amman, they retain a distinct identity based on their origins, socioeconomic conditions, land tenure status (land rental) and political organization

(UNRWA administration) (Greater Amman Municipality, 2008 : Appendix4).

31

Keeping the original UNRWA-Refugee Camp-DPA trinity alive also serves Jordans

strategic interests. It contributes to maintain the authorities good relations with the

refugees and their representatives, while reminding Israel and the international

community that Jordan should not be considered an alternative state for the Palestinians,

as some Israeli political circles would have it. In a longer term perspective, it may also

serve as a basis for compensation claims the Jordanian state may raise in order to ensure

the orderly re-housing and permanent resettlement of those refugees who will not return

to Palestine.48

Conclusion

32

33

34

35

The Palestinian refugee camps do not easily lend themselves to assessment. Indeed,

how can one analyze spaces still defined as temporary six decades after their

establishment ? Following which criteria should one evaluate their management :

relevance to the principle of the right of return or adaptation to the modernization

policies pursued by the host country ?

In Jordan, because most camp refugees are citizens, the issue of their integration/nonintegration has been more sensitive than in any other host country. Although camps are

still considered temporary spaces, they have gradually been covered, with large variations

depending on their urban/rural character, by the surrounding municipalities services.

More recently, they have been included in national developmental policies. The

commercial development that has taken place in some urban camps has reinforced this

trend of socioeconomic integration.

The sensitivity surrounding camp issues has compelled the main stakeholders, namely

UNRWA and the DPA, to implement a relatively flexible mode of governance marked by

adaptation and informality. In the face of mounting demographic pressure, the early

regulations aimed at preserving the temporary character of the camps were informally renegotiated with the refugees in accordance with their evolving needs. However, flexibility

and informality have at times proven tantamount to sheer neglect, for instance with

regard to the absence of decent urban planning schemes. The poor environmental health

conditions prevailing in the camps result from such neglect.

The peace agreement concluded with Israel in 1994 has somewhat questioned this mode

of management. Jordans socioeconomic policies of the 2000s, bent on socioeconomic

modernization and political integration, have prompted the authorities to undertake

unprecedented developmental interventions in the camps. The decline of UNRWAs

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 12 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

margin of manoeuvre as well as the camp refugees new acceptance of large-scale

development schemes have contributed to this policy shift. However, the camps

demographic situation and the structural defects accumulated over decades by its overall

infrastructure are such that only a (highly unlikely) total reconstruction of the camps may

lead to a durable improvement in living conditions.49 Pending the advent of a

comprehensive Arab-Israeli peace agreement, it is likely that the refugee camps will

continue to be sidelined from the major modernization trends affecting Jordans cities in

the future.

Table : Camps of Jordan, main characteristics according to UNRWA sources 50

Camp

Population (mid2000)

Area

Initial

(dunums =0.001

population

sq. km)

Density

(persons

/dunum)

1940s-1950s

Zarqa (1949)

18,509

8,000

180

103

Irbid (1950)

25,250

4,000

244

102

Jabal al-Hussein

(Amman-1952)

29,464

8,000

421

70

Amman New Camp

(Wihdat, Amman 1955)

51,443

5,000

488

103

500

44

>9,000 (6,970 reg.)

5,000

130

69

93,916

26,000

1400

65

1967-1968 emergency camps

Souf (Jerash - 1967)

al-Talbieh (Amman 1968)

Baqaa (Balqa -1968)

>21,900 (20,142

registered with

UNRWA)

Husn (Azm-al-Mufti,

Irbid - 1968)

>26,965 (22,194

reg.)

12,500

774

34

Jerash (Gaza

Jerash - 1968)

>27,600 (24,090

reg.)

11,500

750

37

Marka (Hitteen,

Zarqa - 1968)

>62,379 (45,593

reg.)

15,000

917

68

Source: http://www.un.org/unrwa/refugees/jordan.html.

Bibliography

AL-DALY, Jamal I., Informal Settlements in Jordan - Upgrading Approaches Adopted and

Lessons

Learned,

HUDC,

1999

http://www.hdm/lth.se/fileadmin/hdm/alumni/papers/ad1999/ad1999-09.pdf.

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 13 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

AL-HAMARNEH, A., The Social and Political Effects of Transformation Processes in Palestinian

Refugee Camps in the Amman Metropolitan Area (1989-99), in : Jordan in Transition, edited by

G. Joffe, London, Hurst & Company, 2002, pp. 172-190.

AL-HUSSEINI, J. and BOCCO, R., The Status of the Palestinian Refugees in the Near East : The Right

of Return and UNRWA, in Refugee Survey Quarterly, volume 28, no.2-3, 2009, pp. 260-285.

AL-HUSSEINI, J., CALV, C., SKHIRI, C. Education profile of the Palestine Refugees in the Near East,

IUED/Louvain-La-Neuve/UNRWA survey, Geneva/Amman, UNRWA intranet, May 2007.

AL-HUSSEINI, Jalal, UNRWA and the Palestinian Nation-Building Process. Journal of Palestine

Studies, volume XXIX, Number 2, Winter 2000, pp. 51-64.

AL-KHAZENDAR, Sami, Jordan and the Palestine Question The Role of the Islamic and Left Forces

in Foreign Policy-Making, Reading, Ithaca Press, 1997 :

AWAD, Ahmad, The Culture of the Palestinian Refugee Camp in Jordan (in Arabic), paper

presented at the conference : The National Identity and Culture and their Role in the Reform and

Modernization Process, Amman, The Hussein Cultural Centre, 8-9 March 2008.

BOCCO, Riccardo, UNRWA and the Palestinian Refugees : a history within History, Refugee

Survey Quarterly, no. 2-3, 2009, pp. 1-24.

Community Development and Refugees : Infrastructure, Environment, Housing and Social

Development, paper presented at UNRWA Geneva Conference, Meeting the Humanitarian Needs

of the Palestine Refugees in the Near East : Building Partnerships in Support of UNRWA

(Working Group II, chaired by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan). 7-8 June 2004.

CRISP, J. ; JACOBSEN, K., Refugee camps reconsidered, Foreign Migration Review, December

1998, pp. 27-30 (http://www.fmreview.org/FMRpdfs/FMR03/fmr307.pdf).

DE BEL-AIR, Franoise, Population, politique et politiques de population en Jordanie, 1948-1998,

Thse de doctorat en Dmographie et Sciences sociales sous la direction de Philippe Fargues,

EHESS, Paris, 2003.

Department of Palestinian Affairs (DPA), 55 years in serving refugee camps, Amman, The

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 2004.

Department of Palestinian Affairs (DPA), Five Decades of Responsibility in the Refugee camps of

Jordan, Amman, The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, 2002.

DESTREMAU, Blandine, Lespace du camp et la reproduction du provisoire : les camps de rfugis

palestiniens de Wihdat et de Jabal Hussein Amman . Moyen-Orient : migrations,

dmocratisation, mdiations, ed. Riccardo Bocco et Mohammed-R. Djalili, Paris, Presses

Universitaires de France, 1994.

FARAH, Randa, Crossing Boundaries : Reconstruction of Palestinian identities in al-Baqa Refugee

Camp, Jordan, Palestine, Palestiniens territoire national, espaces communautaires (les

cahiers du Cermoc no.17), Beirut, Cermoc, 1997.

AL-HAMARNEH,

Ala, The Social and Political Effects of Transformation Processes in Palestinian

Refugee Camps in the Amman Metropolitan Area (1989-99), in : Jordan in Transition, edited by

Georges Joffe, London, Hurst & Company, 2002, pp. 172-190.

JABER, Hana. Qu-est-ce quun camp de rfugis , Le Droit au Retour, le problme des rfugis

palestiniens, Paris, Sindbad-Actes Sud, 2002, pp. 233-261.

KHAWAJA, M. and TILTNES, A. On the Margins : Migration and Living Conditions of Palestinian

Camp Refugees in Jordan, Fafo Report 357, 2002. http://www.fafo.no/pub/rapp/357/index.htm.

LAPEYRE, F., BENSAID, M., Socio-economic profile of UNRWA Registered Refugees, IUED/LouvainLa-Neuve/UNRWA survey, Geneva/Amman, UNRWA intranet, 25 July 2006.

League of Red Cross Societies, Relief Operation in behalf of the Palestine Refugees 1949-1950,

Geneva, 1950.

MASSAD, Joseph, Colonial Effects : The Making of National Identity in Jordan, New York,

Columbia University Press, 2001.

RAJFUS, Maurice, Retour de Jordanie : les rfugis palestiniens dans le royaume hachmite. Luc,

La Brche-PEC, 1990.

RAMZOUN, Hussein, The Historical Development of the Refugee Camps in Jordan, in The

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 14 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

Palestinian Refugees Old problems new solutions, ed. Joseph Ginat & Edward J. Perkins,

Brighton, University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, pp. 249-254.

RUEFF, H., VIARO, H., Assessment of Housing Conditions of Palestine Refugees, IUED/Louvain-LaNeuve/UNRWA survey, Geneva/Amman, UNRWA intranet, May 2007.

SABBAGH-GARGOUR, Rana, Controlling the Camp, Jordan Business, July 2006, pp. 114-117.

SALIBI, Kamal, The Modern History of Jordan, London, I.B. Tauris, 1993.

SHAMIR, Shimon, West Bank Refugees-Between Camp and Society, Palestinian Society and

Politics, ed. by J. S. Migdal, Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1980, pp. 146-165.

Tepidness of the Jordanians of Palestinian Origins enthusiasm (special report), al-Sijill, 8

November 2007, p. 5.

UNRWA, Interim Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for

Palestinian Refugees in the Near East, Supplement no.19 (A/1451/Rev.1), 1951.

UNRWA, Report of the Commissioner-General of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency

for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East, 1 July 1954 - 30 June 1955, Supplement no.15

(A/2978), New York, 1955.

UNRWA, Report of the Commissioner-General of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency

for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East, 1 July 1960 - 30 June 1961, Supplement no.14

(A/4861), New York, 1961.

UNRWA, Report of the Commissioner-General of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency

for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East, 1 July 1965 - 30 June 1966, Supplement no.13

(A/6313), New York, 1966.

UNRWA, Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian

Refugees in the Near East, 1 July 197130 June 1972, Supplement no.13 (A/8713), New York,

1972.

UNRWA, Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian

Refugees in the Near East, 1 July 197230 June 1973, Supplement no.13 (A/9013), New York,

1973.

UNRWA, Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian

Refugees in the Near East, 1 July 197430 June 1975, Supplement no.13 (A/10013), New York,

1975.

UNRWA, Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian

Refugees in the Near East, 1 July 197430 June 1975, Supplement no.13 (A/10013), New York,

1975.

UNRWA, Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian

Refugees in the Near East, 1 July 2004 30 June 2005, Supplement no.13 (A/60/13), New York,

2005.

UNRWA, Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian

Refugees in the Near East, 1 January31 December 2006, Supplement no.13 (A/6213), New

York, 2006.

UNRWA, Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian

Refugees in the Near East, 1 January31 December 2007, Supplement no.13 (A/63/13), New

York, 2007.

UNRWA, UNRWA Initiative in Housing and Infrastructure Policy Evolution and the way

ahead (internal document), UNRWA Headquarters, Amman, 2004.

UNRWA, Figures as of 31 December 2008, Public Information Office, UNRWA Headquarters

(Gaza), March 2009.

Notes

1 UNRWA (the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East)

is the humanitarian agency created by the UN General Assembly in December 1949 in order to

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 15 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

cater for the basic needs of poor refugees and promote their social integration in its five fields of

operations: Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank and the Gaza strip. Today, there are 58 official

refugee camps in the Near East : 10 in Jordan, 12 in Lebanon, 9 in Syria, 19 in the West Bank and

8 in the Gaza Strip.

2 The only refugee category that was not granted citizenship are the 40,000-50,000 persons from

the Gaza Strip who were transferred to Jordan in the years following the 1967 Arab-Israeli

conflict, and their descendents. See http://www.un.org/unrwa/refugees/jordan.html.

3 Only a minority of registered refugees across the Near East lives (or has lived) in the camps:

29%. Lebanon is the only host country with a majority (53 %) of refugees living in camps,

although the number of camp refugees there (223,000) is lower than in Jordan (UNRWA, 2009).

4 The refugees and the Arab world as a whole consider that the right of return has been

endorsed by UN General Assembly Resolution 194 (III) of 11 December 1948. Its paragraph 11

resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live in peace with their neighbors

should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be

paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which,

under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the governments or

authorities responsible.

5 Former farmers and labourers made up about three quarters of the total refugee population in

(Trans)Jordan (League of Red Cross Societies, 1950: 44). According to the same source, 99.5 % of

the refugee population was of Palestinian nationality, 84 % of them were Muslim and their

principal districts of origin were Jerusalem, Haifa and Bisan.

6 Apart from these official camps, Jordan hosts three camps (Sukhneh (1969), Prince Hassan

Quarter (1967) and Madaba (1956) that are recognized only as such by the local authorities, and a

series of informal refugee gatherings, namely urban neighborhoods inhabited predominantly by

Palestinian refugees.

7 In UNRWAs opinion, the obstacles to the long-term integration of refugees in the host

countries across the Near East included: (a) the absence of a solution to the Palestine problem

along the lines of General Assembly resolutions regarding repatriation and compensation; (b)

scant physical resources made available for development; and (c) the attitude of the refugees and,

in some cases, of the Governments of the area (UNRWA, 1955: par.34-35).

8 As stated by the Chairman of the Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the

Palestinians (http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/RWB.NSF/db900SID/MUMA).

9 Since the 1990s, the waning influence of the PLO in Jordan has benefitted the Islamists

(Sabbagh-Gargour, R., July 2006; Hamarneh, A., 2002). It is to be borne in mind that in Jordan,

the PLO officials are not allowed to pay any official visit to the camps.

10

See

Freedom

of

assembly

restricted

in:

http://www.humanrightsfirst.org/middle_east/jordan/hrd_jordan.htm. During one of these

breaches, marchers protesting against the killing of the Hamas founder Sheikh Yassin by the

Israelis in Gaza in 2004 created havoc in the Wihdat camp, damaging shops and cars and burning

the Jordanian flag. In the days that followed, the camps leading figures lambasted these actions

and assured that their initiators did not belong to the camp community ; see al-Dustours

opinion : investigating the Wihdat events, al-Dustour, 30/03/2004.

11 In 2005 for example, a survey carried out by the Geneva University and the University of

Louvain-la- Neuve in coordination with UNRWA showed that in Jordan as many as 57% of camp

refugees belonged to the lowest or the lower-mid income quintile compared to 35% of non-camp

dwellers. The gap is wider than in Syria (respectively 49 % and 35 %) and in Lebanon (47 % and

33 %) ; source : Lapeyre, F., Bensaid, M., Socio-economic profile of UNRWA Registered Refugees,

IUED/Louvain-La-Neuve/UNRWA survey, Geneva/Amman, UNRWA intranet, 25 July 2006,

p. 31. Similarly, in 1999, the Norwegian centre FAFO found that 22 % of camp dwellers had a

minimum income of JD 900 or less per year versus a national average of 10 % (Khawaja, M ;

Tiltness, A.A., 2002 : 55-56).

12 In the words of Abdel-Karim Abul Heija, then Director of the Jordanian Department of

Palestinian Affairs in Arab al-Yawm (Jordanian daily), 28 January 2004, p. 2.

13 According to Marouf Bakhit, then Prime Minister, in Arab al-Yawm, 1 June 2006, p. 5.

14 It is widely assumed that UNRWA will only be phased out in accordance with an agreed

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 16 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

timetable of five years following the reaching of such an agreement, as provided for instance in

the informal Taba Accords concluded in January 2001 between Israeli and Palestinian

negotiators. See : From Moratinos Non-Paper, Taba, January 2001, in :

http://www.pij.org/documents/moratinos.pdf

15 In this respect, the fact that the vast majority of the Agencys staff comes from the refugee

communities (namely 29,629 local employees versus 119 international employees in 2009) may

have reinforced the Agencys identification with the refugee cause.

16 In 2009, UNRWAs facilities in Jordan include notably 174 elementary and preparatory

schools; 2 vocational and technical training centres;122 clinics of various types; 14 womens

program centres (including kindergartens); 10 community rehabilitation centres; and 29

distribution centres. About 42 % of these facilities are located in camps (UNRWA, March 2009 ;

internal UNRWA documents).

17 According to the poll carried out by the Institute of Development Studies of the Geneva

University and the Catholic University of Louvain, in cooperation with UNRWA in 2005 (See: J.

AL-HUSSEINI, C.CALV, Ch. SKHIRI, Education profile of the Palestine Refugees in the Near East,

IUED/Louvain-La-Neuve/UNRWA survey, Geneva/Amman, UNRWA intranet, May 2007 : 37).

18 The definition of a Palestine refugee has evolved over time but the main criteria have been the

following: habitual residence in Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948 and loss

of both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict (and poverty until 1992).

From 1950 to 1970, one of UNRWAs main concerns was the relatively high number of false

registrations due to unreported deaths, duplication of registration cards, and fraudulent

registration of non-refugees. While the actual number of Palestinian refugees was estimated at

about 750,000 in 1950, UNRWAs records included 922,000 persons (UNRWA, 1951 : par.35).

Jordan, which was reported to be the host country claiming most of these false refugees, was the

main target of rectification list campaigns undertaken by the Agency until the late 1960s (see for

instance UNRWA, 1966 :22).

19 UNRWAs average annual spending per refugee has fallen from about $ 200 in 1975 to around

$ 110 today. Source: http://www.un.org/unrwa/overview/qa.html.

20 For example, in 2003 the number of primary health facilities per 100,000 persons stood at 1.4

for UNRWA compared to 24 in similar governmental facilities (UNRWA, 2005: 7). In the field of

primary education, the pupil/teacher ratio in UNRWA elementary schools in the academic year

2003-4 reached 34 as opposed to 26 in governmental schools. More strikingly, 92 per cent of

UNRWA schools used the double shift system against 15 % in government primary schools

(UNRWA, 2005 : 8).

21 The number of those refugees who left the camps is undetermined. Informing UNRWA about

address changes is not mandatory. In this way, many refugees who left the camps years ago are

still registered with UNRWA as camp residents.

22 As witnessed by UNRWA in Jordan and other host countries since the early-mid 1970s

(UNRWA, 1973/4: 21, 27; 1974/1975: 29).

23 UNRWA provides occasional technical and financial support to these bodies. The Youth Clubs

presently operate under the authority of the governmental Higher Council of Youth.

24 See for instance: Azayzeh: the preservation of the camps symbolism in order to guarantee the

rights of the refugees to return and compensation in al-Ghad (Jordanian daily), 14 February

2007.

25 The terms of the cooperation between Jordan and UNRWA are notified in a formal agreement

signed

on

14

March

and

20

August

1951

(see:

http://untreaty.un.org/unts/1_60000/3/33/00005646.pdf).

26 Rural camps access to such services has long been less satisfactory. Their inhabitants pay such

taxes to Camp Improvement Committees monitored by the DPA.

27 See http://www.un.org/unrwa/refugees/jordan.html.

28 Most of the camps established in the 1950s are fully built on private land, except the Zarqa

camp, which was erected on predominantly public land (85%). In contrast, the Emergency

camps were mostly built in 1967-1968 on a combination of private and public plots of land,

except the Talbyeh camp (fully on public land). In total, 30.7 % of camp land is public land (DPA,

2002 : 21).

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 17 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

29 Source: http://www.un.org/unrwa/refugees/jordan.html. For an overview of all the camps,

see table Camps of Jordan, main characteristics according to UNRWA sources at the end of the

report. We notice that the emergency camps built following the 1967 Arab-Israeli War are

smaller and less congested than those established in the 1950s.

30 See: http://www.dpa.gov.jo/

31 See http://www.citymayors.com/statistics/largest-cities-density-125.html. Compared with

other host countries, Jordans camp density figures are higher than those of Gaza and the West

Bank (on average 68 and 53 persons per dunum, respectively), and lower than those of Lebanon

and Syria (on average 129 and 77, respectively). Source : UNRWA data in www.unrwa.org/s

Comparatively, the UNHCR warns against setting up of high density camps with populations of

over 20,000 persons because of the environmental and social hazards they bring about (CRISP, J ;

JACOBSEN, K., 1998). As can be seen in table Camps of Jordan, main characteristics according to

UNRWA sources below, some of the camps that were erected in the 1950s host four times as

many refugees (CRISP, J ; JACOBSEN, K., 1998).

32 According to the poll carried out by the Institute of Development Studies of the Geneva

University and the Catholic University of Louvain in cooperation with UNRWA in 2005 (RUEFF,

H., VIARO, H., Assessment of Housing Conditions of Palestine Refugees, IUED/Louvain-LaNeuve/UNRWA survey, Geneva/Amman, UNRWA intranet, May 2007).

33 In: Community Development and Refugees: Infrastructure, Environment, Housing and

Social Development, 7-8 June 2004 (see bibliography), p. 6.

34 The mandate of these agencies has varied over time, mainly in accordance with the evolution of

the Arab-Israeli conflict. The first of these bodies was the short-lived Ministry of Refugees (19491950) which was followed by the Ministry of Development and Reconstruction (the MDR -19511980). In 1980, the Ministry of Occupied Land Territory was established, taking over the MDRs

tasks, although its main aim was to gather information on the situation of Palestinians in the West

Bank and Gaza. (1980-1988). Since 1988, the Department of Palestinian Affairs mandate has

been limited to the camps located on the East Bank of the River Jordan ; see

http://www.dpa.gov.jo/

35 The DPA functions under the umbrella of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

36 In past years, numerous medical, relief and social-oriented NGOs, such as the zaqat (alms)

committees and various CBOs have sought to fill the gaps in the provision of services by UNRWA

and governmental institutions.

37 The DPA also carries out various specific tasks outside camp management, such as

representing the Jordanian government in local and international forums and coordinating with

other governmental bodies on issues related to the movement of people and goods to and from

the West Bank (DPA, 2004: 15-16).

38 The tensions between the authorities and the camp communities have sometimes made it to

the national media. See for instance, Why arent the camp committees elected ? al-Sabil,

(Jordanian islamist weekly (now daily) 12 June 2006, p. 4. or A memorandum demands the

independence of Irbids camp committee at elections, al-Ghad, 7 January 2007, p. 5.

39 See Azayzeh: in favor of the opening of the committees to civil society, al-Ghad, 7 September

2006.

40 According to a survey conducted by Fafo in late 1999, most departures from the camps are

motivated by marriages or other family-related reasons and by work-related considerations (Fafo,

2002: 35-37). Since the 1990s, camps in Amman have also housed foreign immigrants seeking

low-cost housing (Egyptians, Sri-Lankans, Iraqis, etc.). According to informal sources, the Wihdat

camp alone accommodated some 8,000 foreigners in the early 2000s (AL-HAMARNEH, 2002 : 181).

41 According to authorized sources. The value of a shelter actually depends on its location. The

closer it is to the commercial streets, the higher the price. The boom in land prices prompted the

original landowners to regain control over their property in the second half of the 1990s when an

Israeli-Palestinian peace treaty was in the offing. However, as a result of the interruption of the

peace process in 2000, the landowners legal procedures have been suspended.

42

The

CIPs

covered

most

camps

from

1998

to

2002

(see

www.espp.gov.jo/communityinfrastructure.htm). The CIP also included the three unofficial

governmental camps (see footnote 6) that are not recognized as such by UNRWA.

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 18 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

43 See: http://www.espp.gov.jo/housingprojects.htm This is explicitly a sector falling within

UNRWAs area of responsibility but the Agency is unable to meet the needs of the refugees due to

a chronic lack of funds. See Annual Reports of the Commissioner-General of UNRWA, 20042005, par.125 ; and 2006-2007, par.102).

44 The HUDC was created in 1992 to be in charge of housing and urban projects across the

country. It is run by a Council including the Minister of Public Works and Housing and the

Ministry of Planning. See HUDCs website : http://www.hudc.gov.jo/GUI/SubDefault.aspx?

PID=350||Flag=4

45 According to Abd al-Aziz Jabr, former spokesman of the Committee for the Defense of the

Right of Return, in al-Masaiyya (daily newspaper), 14 February 2000.

46 Headline of the Islamist weekly newspaper al-Sabil, 24 December 2000.

47 See also http://www.espp.gov.jo/index.htm

48 According to an American non-paper released in June 2000, over 100 billion dollars were to

be invested in the rehabilitation of refugees over the course of 10 to 20 years according to the

following breakdown: $ 40 billion for the Palestinians, $ 40 billion for Jordan, $ 10 billion for

Lebanon

and

$

10

billion

for

Syria.

See

:

http://christianactionforisrael.org/isreport/mayjun00/nonpaper.html

49 The demolition/reconstruction of camps along sounder urban guidelines was undertaken by

UNRWA and the host countries following armed conflicts. The neighborhoods of the Jenine camp

(West Bank) that were destroyed by the Israeli forces during the Intifada in 2002 were rebuilt in

such a way as to provide its inhabitants with improved living spaces and environmental

conditions. The reconstruction of the Nahr al-Bared camp in the North of Lebanon (wholly

destroyed by the Lebanese army during clashes with Muslim militants in 2007) is to be carried

out according to the same principles.

50 UNRWA does not hold a precise list of camp dwellers and does not take into account nonrefugees renting camp dwellings. UNRWAs population figures therefore often differ from DPA or

NGO statistics.

List of illustrations

Caption Source : UNRWA (http://www.un.org/unrwa/refugees/jordan.html)

URL

http://ifpo.revues.org/docannexe/image/1742/img-1.jpg

File

image/jpeg, 356k

References

Bibliographical reference

Jalal al-Husseini, The Evolution of the Palestinian Refugee Camps in Jordan. Between Logics

of Exclusion and Integration , in Villes, pratiques urbaines et construction nationale en Jordanie,

Beyrouth, Presses de l'IFPO ( Cahiers de lIfpo , no 6), 2011, p. 181-204.

Electronic reference

Jalal al-Husseini, The Evolution of the Palestinian Refugee Camps in Jordan. Between Logics

of Exclusion and Integration , in Villes, pratiques urbaines et construction nationale en Jordanie,

Beyrouth, Presses de l'IFPO ( Cahiers de lIfpo , no 6), 2011, [Online], Online since 06

December 2011, Connection on 05 September 2012. URL : http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Author

Jalal al-Husseini

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 19 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

Copyright

Institut franais du Proche-Orient

openedition:

revues.org

Revues.orgJournals and book series

Journals (342)

Book series (22)

Further information

calenda

CalendaSocial sciences calendar

Events (19486)

Further information

hypotheses.org

Hypotheses.orgResearch notebooks and blogs

Notebooks and blogs (484)

Further information

Newsletters and alerts

NewsletterSubscribe to the newsletter

AlertsAlert service

Freemium

Search

the Journal

OpenEdition

Title:

Collections lectroniques de lIFPO

Livres en ligne des Presses de lInstitut franais du Proche-Orient

Briefly:

A series of online books published by the Institut Franais du Proche-Orient

Collections d'ouvrages publis par l'Institut franais du Proche-Orient

Subjects:

Sociologie, Histoire, Gographie : politique ; culture et reprsentation, Sciences politiques, Archologie,

Proche-Orient

Publisher:

Presses de l'Institut franais du Proche-Orient

Medium:

Papier et lectronique

EISSN:

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 20 of 21

Villes, pratiques urbaines et... - The Evolution of the Palestini... - Jalal al-Husseini - Institut franais du Proche-Orient

9/5/12 9:28 AM

2078-3493

Access:

Open access Freemium

Read detailed presentation

DOI / References

Cite reference

http://ifpo.revues.org/1742

Page 21 of 21

You might also like

- Communication Progressive Du Français Des Affaires PDFDocument18 pagesCommunication Progressive Du Français Des Affaires PDFHicham Cheikh55% (11)

- Une Bouteille Dans La Mer de GazaDocument58 pagesUne Bouteille Dans La Mer de GazaBENNANI100% (1)

- VERGÈS, Françoise - Le Ventre Des FemmesDocument241 pagesVERGÈS, Françoise - Le Ventre Des FemmesRochelle Cristina dos Santos75% (4)

- Memoire Phetdara DanyDocument80 pagesMemoire Phetdara DanyPhetdara DanyNo ratings yet

- L'Invention de L'afrique Des Grands Lacs Par J. P. ChrétienDocument1 pageL'Invention de L'afrique Des Grands Lacs Par J. P. ChrétienKagatamaNo ratings yet

- Antidote 10 Guide Utilisation FR 20201018Document227 pagesAntidote 10 Guide Utilisation FR 20201018david messierNo ratings yet

- Je M'abandonne À Toi JésusDocument3 pagesJe M'abandonne À Toi JésusGloire Luhembwe100% (1)

- Procedures Achats Fournisseurs PDFDocument139 pagesProcedures Achats Fournisseurs PDFsaimima100% (2)

- Arabe Et IsraelDocument10 pagesArabe Et Israelmbenromdhane324No ratings yet

- Dossier 1260 Dossier 1260Document135 pagesDossier 1260 Dossier 1260Nicolás AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Autorité palestinienne: Les Grands Articles d'UniversalisFrom EverandAutorité palestinienne: Les Grands Articles d'UniversalisNo ratings yet

- De Nouvelles Villes Les Camps de RéfugiésDocument9 pagesDe Nouvelles Villes Les Camps de RéfugiésCarmel MounziegouNo ratings yet

- Nakba, Naksa, Nahda Mémoire Et Histoire de La Palestine 1904-2006Document26 pagesNakba, Naksa, Nahda Mémoire Et Histoire de La Palestine 1904-2006volodeaTisNo ratings yet

- PaelstinecetriDocument3 pagesPaelstinecetriFatou100% (1)

- Brevet 2021 - Histoire Géo Corrigé Série ProfessionnelleDocument2 pagesBrevet 2021 - Histoire Géo Corrigé Série ProfessionnelleLETUDIANTNo ratings yet

- Réfugiés Dans Relations Internationales 1944-1951Document7 pagesRéfugiés Dans Relations Internationales 1944-1951Ivette LarsenNo ratings yet

- Rapport Migrants LibyeDocument43 pagesRapport Migrants LibyeFIDHNo ratings yet

- Les Enjeux Politiques Dans La Colonie Du Niger (1944-1960) : Mamoudou DjiboDocument20 pagesLes Enjeux Politiques Dans La Colonie Du Niger (1944-1960) : Mamoudou DjiboSadiksani IdiNo ratings yet

- Le Cedre Et Le Baobab Limmigration SyroDocument88 pagesLe Cedre Et Le Baobab Limmigration SyroMickael GitrasNo ratings yet

- Le Nettoyage Ethnique de La Palestine.Document3 pagesLe Nettoyage Ethnique de La Palestine.farouk.ezzouNo ratings yet

- Alexis Nouss La Condition de L'exiléDocument178 pagesAlexis Nouss La Condition de L'exiléEnrique SchmuklerNo ratings yet

- Brevet 2019 Histoire GeographieDocument4 pagesBrevet 2019 Histoire GeographieAnonymous fIxrD8TS3No ratings yet

- Comprendre Le Conflit Israélo-PalestinienDocument4 pagesComprendre Le Conflit Israélo-PalestinienNico OttNo ratings yet

- Presses Universitaires de Provence: Usages Politiques de La Figure Du Juste: Entre Mémoire Historique EtDocument18 pagesPresses Universitaires de Provence: Usages Politiques de La Figure Du Juste: Entre Mémoire Historique EtplakuNo ratings yet

- Nix NixDocument13 pagesNix NixRoud Youco L'imbattableNo ratings yet

- Bonnecase PDFDocument61 pagesBonnecase PDFyacouba ouattaraNo ratings yet

- L'etat Haïtien Et Ses IntellectuellesDocument6 pagesL'etat Haïtien Et Ses Intellectuelleseventzmichel59No ratings yet

- Juifs Et Musulmans Au Maroc by Mohammed Kenbib [KENBIB, Mohammed] (Z-lib.org)Document273 pagesJuifs Et Musulmans Au Maroc by Mohammed Kenbib [KENBIB, Mohammed] (Z-lib.org)Imane MenhourNo ratings yet

- Décoloniser L'identité Israélienne - Françoise FeugasDocument3 pagesDécoloniser L'identité Israélienne - Françoise Feugaszeineb.guehissNo ratings yet

- Judaisme AlgerienDocument15 pagesJudaisme Algerienbendifmr94No ratings yet

- Les Trois Exils Juifs D'algérie - Stora, BenjaminDocument240 pagesLes Trois Exils Juifs D'algérie - Stora, Benjaminmehdi ber100% (1)

- Les Bushinenge en Guyane Entre Rejet Et PDFDocument32 pagesLes Bushinenge en Guyane Entre Rejet Et PDFDalva LimaNo ratings yet

- The Muslim Emigration in Western AnatoliDocument7 pagesThe Muslim Emigration in Western AnatoliIrfan KokdasNo ratings yet

- Université populaire palestinienneDocument3 pagesUniversité populaire palestiniennefarissaaNo ratings yet

- The Insufficiency of Filipino NationhoodDocument13 pagesThe Insufficiency of Filipino NationhoodSteven consueloNo ratings yet

- La Naissance de La Communauté Imaginée Burkinabè Version PDFDocument119 pagesLa Naissance de La Communauté Imaginée Burkinabè Version PDFIsmael Cedric BENONNo ratings yet

- Histoire Polynésie Chapitre 1Document4 pagesHistoire Polynésie Chapitre 1Tamaeva TapareNo ratings yet

- L'immigration Berbère en FranceDocument3 pagesL'immigration Berbère en FranceAliNo ratings yet

- Limmigrationarabeest-ellelameilleurechosearrivelEurope-TribuneJuiveDocument10 pagesLimmigrationarabeest-ellelameilleurechosearrivelEurope-TribuneJuivegarciadeluisaNo ratings yet

- Michelet Le - Peuple GrangeDocument30 pagesMichelet Le - Peuple GrangeTarek daymiNo ratings yet

- 114 Cohen Orisha JourneysDocument21 pages114 Cohen Orisha JourneysJavier PerellóNo ratings yet

- Le Peuple Juif Revue (... ) Fédération Sioniste bpt6k58660206Document18 pagesLe Peuple Juif Revue (... ) Fédération Sioniste bpt6k58660206nabil abderrahmaneNo ratings yet

- Les Effets de La Cooperation Sur La Concurrence en SpiritualiteDocument40 pagesLes Effets de La Cooperation Sur La Concurrence en SpiritualiteneolgerardNo ratings yet