Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Archaic Olive-Oil Extraction Plant in Clazomenae

Uploaded by

Thanos Sideris0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

157 views15 pagesabout olive oil extraction

Original Title

Archaic olive-oil extraction plant in Clazomenae

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentabout olive oil extraction

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

157 views15 pagesArchaic Olive-Oil Extraction Plant in Clazomenae

Uploaded by

Thanos Siderisabout olive oil extraction

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 15

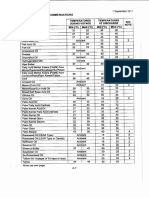

a cree ees Teton ee

; Eee aecog

THESSALONIKI 2004

Archaic Olive Oil Extraction Plant

in Klazomenai”™

Elif Koparal and Ertan Iplikei

he recent excavations at Klazomenai,

eo which is well-known as a centre of major

pottery and sarcophagi manufacturers

during the Archaic period, produced significant

evidence related to another industrial activity,

namely the production of olive oil. To date, two

olive oil extraction plants have been discovered at

Klazomenai. One of these was located on the south

slope of the acropolis, the industrial district of the

city, where pottery kilns and a bone-carving

‘workshop were also present. The other olive oil

extraction plant, which is the subject of this study,

‘was located on the west side of the modern road

between iskele and Urla, in HBT (Map B), where

an iron-processing workshop and a well-defined

Grainage system and two wells, also dating to the

Archaic period, were uncovered.

Even though olive oil has always been a very

important commercial commodity and a very

‘common source of nutrition, the olive extraction

process in the ancient world is not widely under-

stood. For this reason, it is necessary to include

some brief information about the process of olive

oil production before discussing the peculiar

features of the Klazomenai Olive Oil Extraction

Plant. Palaeobotanical research in the Mediterranean

basin proves that wild olive trees existed in the

region before the end of the Tce Age,! but unfortu-

nately evidence for its domestication is much less

abundant. It has been suggested that olive trees

were cultivated as early as 2500 in Crete and that

the large pithoi found in the Cretan palaces were

ai

used for the storage of olive oil Both organic and

material evidence suggest that the eastern coast of

the Mediterranean must have been a centre for

olive growing and olive oil production. The earliest

evidence for olive extraction comes from the

‘eastern Mediterranean coast and Cyprus, and dates

to the Late Bronze Age.? By comparison, the avail-

able evidence about olive oil extraction is very

scanty in the Acgean basin and limited to surface

findings only which are relatively late in date. The

Klazomenai Olive Oil Extraction Plant thus repre-

sents a very significant discovery, since it is so far

the only installation for oil production preserved

with its own datable small finds and permanent

elements, in Asia Minor.

‘The procedure of extracting olive oil has not

changed since antiquity. In modern times the

methods used at small-scale local workshops are

essentially the same with only rhinor modifications,

fn spite of new technological developments. This

may be due to conservatism or to economical

reasons. The first stage, the picking of the olives,

was preferably done by hand or by shaking the

branches. It takes place in October when the fruits

begin to get ripe. The depiction of an olive harvest

scene on an Attic black-figured amphora attri-

buted to the Antimenes Painter, shows that it was

done in the same way as today (Fig. 1). After the

harvesting, the following stages involved croshing,

pressing and distilling the olive oil. The olives were

ground either manually with simple portable

mortars, or with « more advanced apparatus, a mill

‘The paste obtained from the olive crushing was

222 Symposivom “Klazomenci, Teos and Abdera: Mecropoleis and Colony”

Fig. 1. Olive harvest scene on Attic black-figured neck-

amphora attribuied to the Antimenes Painter. London,

British Museum, B 226 (ABV 273.116). After R. Frankel,

S Avitsur and E. Ayalon, History and Technology of Olive

Oil in the Holy Land (Tel Aviv 1984) 24 fig, 11

poured into woven sacks which were then placed on

the pressing bed to be squeezed. During the press-

ing process, hot or more usually cold water was

poured over the sacks to drain every drop of oil off

the pulp. The final stage was the separation of olive

oil from water. The existing evidence reveals that

there was more than one method to distil olive oil.

‘The simplest was to collect the mixture of olive oil

and water in # vat and to leave it to settle for a

while, so that the olive oil would rise to the surface

due to its lighter density. Then it could be skimmed

off with ladles. A more developed apparatus

featured a tank with a faucet at the bottom which

‘was used to drain off the residue as the water sank

down, Such tanks were in use in the small focal

‘workshops in the Aegean region until recent times.

Annumber of pits, which represent the permanent

elements of the Klzomenai Olive Oil Extraction

Plant, were hewn into bedrock and were preserved

with their own datable finds, thus providing us with

the opportunity to identify the functions of the

elements and to establish a chronology for the

plant (Fig. 2). Only scanty remains of carbonized

‘wood and afew nails were found in the pits indicat-

ing that the devices placed inside must have been

made of wood. The portable parts of the install-

ation seem to have been carried away after the

abandonment of the plant. The pits were un-

covered below remains of Roman edifices and a

Basileia complex dated to the second quarter of the

fourth contury.* There were eleven pits of different

size and shape in the main room of the plant. The

storage spaces were located to the north and west

of the main room, The presence of more than one

Fig. 2. Klazomenai. Aer-

ial view of the Olive Oil

Extraction Plant and the

storage space of the

second phase including a

Late Antique cistern,

, Koparal and E ilii, Archaic Olive Oi! Baraction Plant in Klacomenai 223

element serving the same function indicated that

two different systems were used at this plant. Two

press and separation devices were found, while the

crushing basin appears to have been part of both

systems. The two systems appear to have belonged

to two different phases according to the material

evidence which revealed that the smaller-sized

press and collecting vat were terminated earlier

than the larger ones. Apparently the smaller and

simpler devices were replaced with more advanced

versions in order to satisfy the demand for

increased production capacity in the beginning of

the second phase.

First Phase (Figs 3-4)

‘The system applied during the first phase of the plant

‘was quite simple in comparison with the one used in

the second phase, which directly involved the intro-

duction of new technologies. The pits that were used

for the placement of the devices in the first phase are

numbered 1-4 on the plan. Pit 1,2 round depression

ig. 4. Klazomenai Olive Oil Extraction Plant; reconstniction ofthe frst phase (E. plik)

224

‘Sympositom “Klacomenai, Teos and Abdera: Mesropokeis and Colony"

ig. 5. Klazomanai Olive Oi! Extraction Plant; hypothetical reconstruction of oteril (Ei)

with a cavity at the bottom, served for the first stage

of oil extraction, the crushing of the olives.> The

round cavity at the bottom of the basin was used for

the placement ofthe socket ofthe mill which stabilized

the device. In order to prevent the gnawing of the

surface at the bottom of the basin from the friction

caused by the turning of the millstones, the bottom

‘must have been either paved with stone slabs carved

out of rock or, more likely, a gap may have been left

between the millstones and the floor, what would also

prevent the crushing of the olive pits The location of

thc crushing basin, adjacent to the western border of

the main room, presumably facilitated the hauling of

the olives into the basin through a window in the

western wall. On the other hand, its location must

have prevented anyone from meking a whole torn

around it, since there was not enough space.

‘Therefore we assume that a flat wooden plank on

four feet was placed above the crushing basin to

accommodate the control of the millstones with the

aid of an arm connected to the mill (Fig. 5).

‘Tae filling debris in Pit 1 consisted of two layers

of different texture. The relatively loose layer at the

bottom strongly argue that it was formed uninten-

‘

Fig. 6 . Toe fragment of a Clazomenian amphora, fourth

century (E. Koparal); b Terracotta lamp, Archaic or fourth

century (E. Koparal);¢. Chian kantharos, last quarter of

the sith century (E- Koparal); d. North lonian banded

bowl, second half ofthe sith century (F. Ydmaz)

E, Koparal end E.Iplksi, Archaic Olne Oil Beracion Plant in Klazomenai ms

tionally after the abandonment of the plant. A

Chian kantharos (Fig. 6c)? and a North Ionian

banded bow (Fig. 6d)® dated roughly to the second

half of the sixth century were found in this layer.

The layer above this was homogeneous with the

layer formed during the fourth-century levelling for

the construction of the large mansion, the Basile,

‘A Clazomenian amphora toe (Fig. 6a)? and a

terracotta lamp (Fig. 6b)!9 dated to the fourth

century were recovered in this layer.

‘The rectangular Pit 2 and the conical Pit 3

served for the placement of the press device in the

t phase. The shallow cavities on the sides of Pit

2 were used to stabilize the slotted piers made of

‘wood, where one end of the press beam was hinged;

the other end was pulled down by human power

supported by weight stones, during the pressing

process. The press bed, presumably made of wood,

must have been placed above Pit 3, in which any

dripping from the sacks would be collected, before

the start of the pressing procedure."! The rounded

bottom of Pit 3 undoubtedly enabled the oil accu-

mulated in it to be collected.

it 4 with a round conical depression hewn into

bedrock, was located right next to the press device

and served as the collecting vat, It is highly likely

that a gutter connected the press bed with a vessel

placed in this pit, where the mixture of olive oil and

‘water obtained from the pressing was transferred in

order to be distilled. The vessel in Pit 4 could have

beena simple jar, in which the olive oil rising up was

skimmed off, or, perhaps more likely, could have

been a jar with a faucet at the bottom which would

have allowed the removal of the excess water and

residue which sank down, An Attic skyphos bears a

depiction ofa single-beamed lever and weight press

device, similar to the one in Klazomenai (Fig. 7).

“The original fill in Pits 2 and 4 was laxgely dest-

royed during the construction of the Basileiain the

fourth century, but fortunately a part of the

1 fill preserved at the bottom produced

material evidence suggesting a date for the annul-

ment of these elements. A fragmentary Chian

amphora (Fig. 8a)"2 dated to the last quarter of the

sixth century was found in this layer at the bottom

of the press. The rest of the filling above was dest-

royed and replaced with large stones to reinforce

the foundation of a wall laid in an east-west direc-

tion, which belonged to the Basileia. Pit 5 of the

second phase, which was located next to the press

Fig. 7. Attic black-figured skyphos depicting olive oit

‘pressing with human power and weight stones. Boston,

Museum of Fine Arts, 99.525 (H.L. Pierce Fund). After L.

Foxhall, “Oil Extraction and Processing Equipment in

Classical Greece” in M-C. Amoureti and J-P. Brun

(eds), La production du vin et de Uhuile en Méditerranée

(BCH Suppl. 26) (Paris 1993) 185 fg. 1

aes

®

Fig. 8a. Rim fregment of bulbous-necked Chian amphora,

last quarter of the sixth centuy (F. Yilmaz): b. Ac

Dlackeglazed stemmed bows, late sith century (E. Koparal)

226 ‘Symposiums “Klazomenai, Teos and Abdera: Metropoles and Colony”

bn

Fig. 9. North-south section of Olive Oil Extraction Plant (E. Koparal)

of the first phase, was also filled with large stones

to provide a robust foundation for the Basileia

‘The small vat assumed to be located below the

press table was not disturbed during the construc-

tion of the Basilefa and a black-glazed Attic bowl

(Eig. 80), dated to the fate sixth century, was

found in it, It is not possible to suggest a precise

date for the beginning of the first phase based on

the preserved evidence. However, datable ceramic

sherds found in the pits of the first phase provide

4 tetminus post quem for the beginning of the

second phase, since these pits were filled in order

to form a level surface for the installation of the

devices of the second phase,

‘The storage space of the first plant located to

the north of the main room, was a chamber cut into

bedrock. Its borders are not yet firmly determined

due to the presence of foundation walls belonging

to the Basileia, but it may be that the storage space

bordered the main room to the north and east. The

floor level of the storage space was almost a meter

below the main room, Itwas presumably entered by

a portable. ladder placed on the northern wall,

since no doorway opening to the depot was identi-

fied. On the floor of the chamber there were

conical depressions hewn into the bedrock, which

must have been used to stabilize the bottom of

large storage jars. No such jar was preserved in situ,

but great quantities of pithoi fragments were found

scattered around. A pithos was found in situ sunken

into the floor, and two floors were identified in the

‘area around it (Fig. 9). The first floor was a stone

pavement surrounding the rim of the pithos while

the second one above it, made out of beaten earth,

was almost 0.20 m thick. It is highly likely that the

pithos was used to collect the olive oil which

dripped down, since the stone-paved floor was

levelled to the rim of the vessel.

‘The conical depressions on the floor of the

storage space were filled and a level was formed

with the beaten earth floor. The foundation of a

wall running in an east-west direction, located

parallel to the northern border of the main room,

had destroyed both floors, indicating clearly that

the wall was constructed at a date later than both

floors. Although we are dealing here with a

complex stratigraphy, the ceramic finds suggest a

valid answer to the questions about the function of

the floors and the wall. An Attic black-glazed bowl

(Fig. 10a), the rim fragment of an olpe (Fig

10b),} and a one-handled bowl (Fig. 10c)!° were

‘ ,

Fig. 10.4. Attic bowl, late sith contury (F. Yulmaz); b. Ria

Sragment of North Ionian olpe, late sith century (FE.

‘Koparal); . North Ionian one-handled bow, late sixth

century (F. Yilmaz)

E, Koparal and E, Iplikei, Archaie Olive Oil Feeracion Plant in Klazomenai 27

found below the earth floor and indicate that this

floor was made no earlier than the last quarter of

the sixth century. The consistency of the filling in

the conical cavities was comparable with that of

the units belonging to the first phase. An olpe (Fig

Lia),}7 and an Attic black-glazed Type C cup (Fig.

L1b),!® both dated to the last quarter of the sixth

century, were found in those cavities and verify

that they were terminated at the same time as the

press and the collecting vat of the first phase, We

may conclude that this storage space was used

uring the first phase of the plant, but it must have

also been in use for 2 certain period at the beginning

of the second phase until the completion of the

second, larger storage space. The stone pavement

and the conical cavities in the bedrock were used

uring the first phase, whilst at the beginning of

the second phase a new level was formed with the

construction of the earth floor and by filling in the

conical pits solidly. ‘The presence of the second

depot and the wall constructed in the first storage

chamber suggest that the first depot went out of

use after the completion of the larger depot and

that the wall was then built to border the northern

side of the main room.

~~

Fig. 11 a, Rim fragment of Norte fonian ole, late sith

century (E. Koparal);b, Attic black glazed Type C cup (E

Koparl); c. Ati blackeglazed bow, ca 380 (F. Yalmaz);

4 Aitic black-glazed bon, ca 380 (E. Koparal)

Second Phase (Figs 12-13)

‘The second phase of the Klazomenai Olive Oil

Extraction Plant directly involved the introduction

of new technology in order to fulfill the demand for

increased production capacity. The elements of the

second plant are numbered 1, 5-8 (a-f) on the plan.

‘As mentioned above, Pit 1, the crushing basin, was

‘used for the same purpose in the second phase as

well. The pits in which the press device and the

collecting vat of the first plant had been placed,

‘were no longer used, a level surface was formed,

‘and a new press and three-compartmented separ-

ation tank were installed. These new devices were

not only larger in size, but also owing to certain

technical modifications were of increased capacity.

‘The compounds of the second press are numbered

8.a-fon the plan, The rectangular pit (8f) dug in an

east-west direction was used for the placement of

the slotted piers of wood where the one end of the

‘beam was fixed. The cavities on the sides of the pit

Fig. 12. Ground plan of the second phase.

228 Symposinm "Klazomenai, Teos and Abdera: Mesropoeis and Colony”

provided stability for the wooden panels into which

the end of the beam was hinged. Three circular

shallow depressions (82-c), located in front of the

rectangular pit, served for the placement of the

‘wooden trunks that supported the press bed. Two

small conical pits in the middle of the three round

depressions were identical with Pit 3 of the first

phase in terms of size and shape. Evidently those

Fig, 13. Klazomenci Olive Oil Ex-

traction Plant; reconstruction of the

second phase (E. iplikei)

pits also had the same function, which was to catch

any amount of oil dripping from the sacks filled

with the olive pulp. It is not surprising that in the

second phase there were two such pits instead of

one due to the expanded amount of pulp pressed at

Fig. 140, Klazomenai Olive Oil Extecton Plan; hypothetical reconstruction of press device used in the second phase (E.

Ils); b. Kazomenai Olive Oil Extraction Plan; bluprine of res device (E.Ipik)

E.Koparal and ffl, Archie Olive Oi! Beaton Plant in Klazomenai 229

Fig. IS. Klazomenai Olive Oil Extraction Plant; hypothet-

fecal reconstruction of fork-shaped press bear used in the

second phase (E. Inlikci)

cone time (Fig. 14a-b). The long width ofthe rectangular

pit suggests that a fork-shaped beam was used

instead of a single one in order to keep it balanced

(Fig. 15).2 ‘The rough alignment ofa square-shaped

pit (number 9 on the plan) with the proposed

location of the press beam strongly argues that a

pulley was connected to the beam in order to

reduce time and energy during the pressing process

(Fig. 16) The use of such a capstan is a remark-

able technological novelty applied to the press

device of the second phase.

‘The final stage of olive oil production, namely

the separation of oil from the bitter juice and water

was done manually in the first phase. The intro-

Fig. 17, Reconstructed view of the three-compantment separation tank (E. Iplitsi)

230 Symposium “Klazomenai, Tes and Abdera: Meropoles and Colony”

duction of a three-compartment separation system

(Pits 5, 6 and 7) in the second phase provided con-

tinuous distillation (Fig, 17). The mixture of oil and

water was transferred from the press into Pit 6 with

‘gutter connecting the two and was left to settle for

awhile. The oil, which is naturally lighter in density

rose to the surface and flowed into Pit 5, while the

water sank and passed through a hole with a

stopper into Pit 7. Thus, the separation process was

done without interruption and provided continuous

production, thus allowing greater production

capacity.

‘The ceramic sherds found in the pits that served

as the permenent elements of the second plant ate

dated exclusively to the fourth century. An Attic

black-glazed bowl (Fig. 11)” and a Clazomenian

amphora (Fig. 18b)”? were found in the pits of the

press device. Pits 5-7 that served for the separation

of oil and water also included ceramic material

dated to the second quarter of the fourth century.

An Attic black-glazed saltcellar (Fig. 11d)" and an

Aitic black-glazed fish-plate (Fig. 18a)" found in

the separation tanks confirmed that the pits were

filled in the fourth century.

As mentioned above, another storage space,

larger in size, was built in the second phase to

handle the increased amount of production. This

chamber, likewise hewn into bedrock measured

4.80 m x7.50 m, and was located to the west of the

‘main room (Fig. 19.1). This storage space was also

filled in the fourth century during the construction

of the Basileia. A Clazomenian amphora (Fig

18c)°5 accompanied by an Attic black-glazed bowl?

were found on the floor of the depot, showing that

this was filled at the same time as the other

elements of the second plant,

The presence of ceramic sherds dated to the

fourth century in the units of the second phase

could well give the incorrect impression that the

second plant was used until the fourth century. As

will be mentioned below, however, a hiatus

between the end of the sixth century and the

beginning of the fourth century has been observed

at both the living quarters and the burial grounds of

Klazomenei. Taking this into account, we may

claim that the elements of the second plant

i

Fig, 18 0, Antic black-glaced fisk-plate, early fourth cen-

tury (R. Yilmaz); 6, Rim fragment of Clazomentan

amphora, fourth century (B, Koparl);c. Rim fragment of

Clazomenian amphora, fourth century (E. Koparal)

remained at the site during the fifth century and

that they were then removed by the builders of the

Basileia, At the same time, the pits that had served

‘as the permanent elements of the plant were filled

solidly to form a level for the foundation of the

Jarge mansion in the fourth century.

‘There were no remains of the walls or any

evidence for the roof of the plant, other than a few

disintegrated mud-bricks. Nonetheless, the

evidence from the other sectors for the architecture

of the Archaic period at the site provides some

hints regarding the superstructure of the Olive Oil

Extraction Plant. Stone wall socles topped by

E., Koparal and E.Ipliksi, Archaic Olive Oil Betraction Plant in Klazomenai 21

Fig. 19. Ground plan of Olive Oil Bxraction Plant , Main compound; I. Storage area ofthe frst phase; I. Storage area

of the second phase.

mud-bricks are typical for the domestic units. It is

natural to assume that the same masonry will have

beon used for the Olive Oil Plant as well. There are

two types of roofs that may be suggested: a hipped-

thatched roof made of organic material (Fig. 20)"”

or a flat roof composed of beaten earth. A tiled

roof is not an option, since the excavations at the

‘Archaic settlement revealed no evidence for the

use of terracotta roof tiles during this period.

Dating

‘The chronology of the Klazomenai Olive Oil

Extraction Plant must be established after exami

ing the historical events that took place in Klaz0-

‘menai. The excavations carried out at the living

quarters and the necropoleis of the city exposed a

hiatus between 550/546-530 in Klazomenai. Even

‘though itis difficult to determine such a short gap

accurately, the lack of Attic pottery dated to this,

period at the settlement and the burial grounds

confirms that the mainland of Klazomenai was

Fig. 20. Clazomenian sarcophagus imitating a house with

2 hipped-thatched roof. Akpmar necropolis, late seventh

century (E. iplikgi)

232 Symposi "Klazomenci, Teor and Abdere: Mesropoleis and Colony”

either not inhabited between 550/546-530 or that

the settlement was diminished.2* This corrclates

well with the ancient sources. The ceramic sherds

found in the compounds of the plant belonging to

the first phase are dated to the last quarter of the

sixth century. Based on this evidence, the beginning

of the second phase must be placed in the last

quarter ofthe sith century. Taking into consideration

the hiatus between 550/546-530, we may assume

that the second Olive Oil Extraction Plant started

to operate around 530/525 and since the mainland

‘was not inhabited between 550/546-530 the first

plant must have been used during the first half of

the sixth century,

‘The ancient sources state that Klazomenai and

Kyme were invaded by the Persians a year after the

Tonian Revolt, which began in 499 (Herodotos

5.123). As a result of the Pers

Clazomenians moved to the island with fear

(Pausanias 7.3.9). The excavations at the settlement

and the burial grounds indicate a long hiatus, which

lasted during the fifth century. The test soundings

on Karantina Island indicated that the inhabitants

of Klazomenai abandoned the mainland and

moved to the island.

Consequently, given the stratified material

evidence, which agrees

the second plant must have been used until the

beginning of the fifth century. Its highly likely that

the devices of the plant were disassembled and

‘carried away in order to be re-used. The area was

inhabited once more a century later and the plant's

pits were filled to form a strong foundation for the

Basileia in the early fourth century.

fn invasion the

the historical events,

Conclusion

‘The Klazomenai Olive Oil Extraction Plant is @

reflection of the intellectual and practical

environment, which led to the emergence of the

Pre-Socratic philosophers and scientists of Tonia,

who laid the foundations of moder science.

Certain modifications applied to the plant in its

second phase directly involved the introduction of

new technologies that greatly improved the olive oil

extraction process. These are: the application of

the three-compartment separation system, the use

of a rollermill functioning with a pair of millstones

and the introduction of « capstan used in the press-

ing stage, which allowed greater production cap-

acity and dramatic drop of the time and energy

consumed in the process. The extraction plants and

the technical knowledge they evidence strongly

suggest that olive oil became an important trade

‘commodity for the Clazomenians in the second half

of the sixth century. Klazomenai became a centre

of olive oil export trade, rather than just a local

producer with limited capacity. Some, at least, of

the Clazomenian transport amphorac found at

various sites on the Mediterranean and Black Sea

coasts may have carried Clazomenian oil.

Ortadogu Teknik Universitesi

‘Yerlesim Arkcolojisi Anabilim Dali

Mirmarlik Faktiltesi, Yeni Bina, No. 410

‘TR-Inénii Caddesi Ankara 06531

Altintas Mahallesi

Ege Sokak, No. 4

‘TR-Urla 35430

Abbreviations

Agora XIL = B.A. Sparkes and L. Talcott, Agora XIL

Black and Plain Pottery of the 6th, 5th and 4th

Centuries BC (Princeton 1970)

Dojer, “Amphores” = E. Doer, “Premitxes remar-

‘ques sur let amphores de Clazoménes” in J.-Y.

Empezeur and Y. Garlan (eds), Recherches sur les

amphores greeques, Actes du Colloque international

‘organisé par le Centre National de ta Recherche

Scientifique, 1" Université de Rennes I et Ecole

Francaise d'Athones. Athones, 10-12 septembre 1984

(BCH Suppl. 13) (Paris 1986) 461-471.

KST = Kan Sonuglan Toplants:

Notes

* We would like to thank Professor Given Baiar for

giving us the opportunity to study and publish the

Azchaic Olive Oil Extraction Plant in Klazomenai,

All dates are BC unless otherwise stated.

1. HLA. Forbes and L, Foxhall, “The Queen of All

‘Trees: Preliminary Notes on the Archaeology of the

Olive” Expedition 21.1 (1978) 38.

2. RI. Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology 3 (Leiden

1965) 104, For a ertical review of the available mate~

B

10.

Kopzrl and E, Iplitgi, Archaic Ove Oi! Exton lenin Klazomenci

rial regarding botanical and archacological evidence

for the olive in the Prehistoric Aegean see C.N.

‘Runnels and J. Hansen, “The Olive in the Prehistoric

‘Aegean: The Evidence for Domestication in the

Early Bronze Age” OxfTA 5 (1986) 299-308,

SS, Hadjisawas, “Olive Oil Production in Ancient

Cyprus” RDAC 19882, 111-120.

G, Balar and Y. Ersoy, “1997 Yih Klazomenai

Gahigmatant” KST 20.2 (1998) 67; G. Bakar et at,

1999 Klazomenai Kazisi” KST 22.2 (2000) 33.

‘There is no substantial evidence to determine that

the crushing basin was also used during the first

phase, Our assumption is based om the lack of any

other device that could be used for this process. At

the other contemporary plants a oylinder roll on a

flat top was used to grind the olives. In Klazomenai

a cylinérical rock was found, but this is not sufficient

‘to suggest that such a tool was used in the first phase

instead of the crushing basin, as a bed was not found.

For such examples see R. Frankel, S. Avitsur and E,

Ayalon, History and Technology of Olive Oil in the

Holy Land (Tel Aviv 1994) 187, figs 290 and 31a,

During conversations with local olive oil producers,

‘we were informed that if the olive pits were crushed

the oil would have an unpleasant bitter taste,

Similax examples of white-slipped small Chian kan-

tharoi were found at the Emporio on Chios in layers

dated between 550-500: J. Boardman, Excavations in

Chios 1952-1955, Greek Emporio (BSA Suppl. 6)

(London 1967) 161-162 figs 109.763-764, pl. 60.763.

Other similar examples are roughly dated to the

second half of the sixth century: A. Lemos, Archaic

Pottery of Chios. The Decorated Styles (Oxford 1991)

195-177, pl. 214 no. 1635.

Similar bended bowls were found at Tocra in de-

posits dated between 560-510: J. Boardman and J.

Hayes, Excavations at Tocra 1963-1965. The Archaic

Deposits | (BSA Suppl. 4) (London 1966) 55-56 fig.

28.146, 760, pl. 38.751, 759; td., Excavations at Tora

1963-1965. The Archaic Deposits Hand Later Deposits

(BSA Suppl. 10) (London 1973) 23-24 fig. 9.2038. For

further discussion on the banded bowls from Kiazo-

menai see Y.E. Ersoy, Clazomenae: The Archaic Ser

Iement (Ph.D Diss., Bryn Mawr College 1993; Ann

‘Axor 1996) 373-378.

‘This amphora type, which is most likely a local

production, is found in great quantities in the fourth-

century settlement, For farther discussion see Doier,

“Amphores” 469, fig. 15.

‘One cannot be precise on the dating of this simple

plain lamp. Itis a type which is extremely common at

the site particularly throughout the sixth century.

233

‘Some examples, however, randomly attested in the

fourth-century houses suggest that the type

‘continued also in the Classical era. For Archaic

examples of the type cf. KF. Kinch, Fouilles de

Vroulia (Belin 1914) 159-160, pl.27-Sa-b and 27.10a-

b.

LI. Even today at small workshops, a vessel is placed

below the press table o catch the oil dripping off the

sacks as this pure oil which is not yet mixed with

water is of the highest quality.

12, CE W-D. Niemeier, “Die Zierde Toniens" 44 1999,

405, fig. 28.17.

13. CE Agora XII 140-141, 304 no. 969, pl. 35.

14, Similar examples of Attic black-glazed bowis from

the Athenian Agora are dated between 525-500:

Ibid. 125, 288 no. 727, pl. 30.

15, For an identical example of an olpe found at Miletos

and dated to the late sixth century sce W.

Voigtlinder, “Funde aus der Insula westlich des

Buleuterion in Milet” IstAfite 32 (1982) 46 fig. 8.53,

120 no. $3, pl. 17. For another example found at Old

‘Smyrna and dated to the same period sce J.M. Cook,

“Old Smyrna, 1948-1951" BS4 53-54 (1958-59) 29,

pi. db (right).

16, This type of one-handled bowls is extremely common

fn the late sixth-century deposits at the site. For

further discussion see Ersoy, op.cit (n. 8) 378-380.

For the specimens from Miletos, randomly attested

in the Late Archaic-Early Classical contexts see

Niemeier, op.cit. (n. 12) 384-385 figs 14-15;

Voigtlinder, op.cit. 81 fig. 39.241. For another

‘example from Olbia found in a grave with goods

ated to the end of the sixth century see V.M, Skud-

nove, Arkhaicheskii Nekropot’ Ol'vi [Archaic Necro-

polis of Olbia] (Leningrad 1988) 132 no. 208,

17. See note 15, above

18, Cf, Agora XII 91-92, 263-264, no. 398, fig. 4; H.

Bloesch, Formen attischer Schalen von Exekias bis

zum Ende des strengen Stils (Bern 1940) 119-124, pls

32a, 334.

19, Fork-shaped beams were used at installations in

Israel until the recent times: Frankel eta, op.cit. (0.

5) 172, fig, 477.

20, In Israel and Cyprus the use of capstans was intro-

‘duced much later: Frankel et al, pci, figs 42-45;

Hadjisawas, Olive Oil Processing in Cyprus from

Bronze Age to the Byzanilne Period (SIMA 99) (Ni-

‘cosia 1992) 33 and fig. 59.

21. There are similar examples of Attic black glazed.

bowls found at the Athenian Agora that are speci

‘ally dated to 380: Agora XII 134, 298 no. 876,

pl 33.

234 Symposium “Klacomenai, Teo and Abdera: Meropoteis end Colony”

22, The type of Clazomenian amphora found in the

‘press unit is extremely common in the fourth-century

deposits at the site. For further discussion see Doier,

“Amphores” 469, fig. 15.

23, Cl. Agora XII 135, 299 no. 882, fig. 9, pl. 33 (dated 10

380).

24, tis dated to the early fourth century, in accordance

vwith similar examples found at Old Smyrna: LM.

Cook, “Old Smyrna: Fourth-Century Black Glaze”

BSA 60 (1965) 152-153 fig, 10.1

25. Dor, “Amphores” 469, fig. 15.

26, For similar examples of black-glazed bowls, highly

likely associated with local Ionian workshops see J

Boehlau and K. Schefold, Larisa am Hermos II. Die

Exgebnisse der Ausgrabungen 1902-1934. Die Klein

{unde (Berlin 1942) 184 fig. 894; Cook, op. ci. (n. 24)

147-148 figs 4.1-2, 5, pl. Sa.

21. This terracotta sarchophagus dated to the early years,

of the sixth century was found at the Akpinar necro-

polis during the 1999 campaign. Its lid is shaped like

a hipped-thatched roof and indicates that this root

model was in use during the sixth century.

28, YE. Ersoy, “Klazomenai in the Archaic Period” inJ.

Cobet, V. von Graeve, WD. Niemeier and K.

Zimmermann (eds), Fakes lonien: eine Bestandauf-

nahme, Akten.des Intemationalen Kolloguiwms zum

einhundertidhrigen Tubilaum der Ausgrabungen in

Miles, Panionion/Gizelcamls, 26.09.-01.10.1999 (ia

press, tobe published in 2004); id, supra 60-64,

28. The social order of Ionia was greatly upset asa result

of the offensive intention of the Persian King Cyrus

‘and the fear caused by looters that accompanied the

Persian forces. The hiatus observed in the burial

‘grounds and the living quarters of the city should be

associated with the abandonment of the city by the

Tonians, who fled with fear. To make a suggestion

about the settlements of that period would not be

‘more than a mere guess, however we may claim that

the Clszomenians had spread around the villages and

the surrounding islands and if the mainland was

inhabited the settlement must have been restricted to

‘a small area,

30, See Giingbr, supra 121-131, esp. 124-129.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- A S AB H T I: Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 215 (2020) 104-112Document11 pagesA S AB H T I: Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 215 (2020) 104-112Thanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Wagner Pernicka 1984 TroasMetalDeposits InGermanDocument37 pagesWagner Pernicka 1984 TroasMetalDeposits InGermanThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Sideris 2021 Review of Hanslmayr R Die-Skulpturen-Von-Ephesos Die-HermenDocument3 pagesSideris 2021 Review of Hanslmayr R Die-Skulpturen-Von-Ephesos Die-HermenThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 2018 - Levy - Sideris - Et - Al. - At-Risk - World - Heritage PDFDocument106 pages2018 - Levy - Sideris - Et - Al. - At-Risk - World - Heritage PDFThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Harris NikokratesOfKolonosDocument10 pagesHarris NikokratesOfKolonosThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- 2018 - Levy - Sideris - Et - Al. - At-Risk - World - Heritage PDFDocument106 pages2018 - Levy - Sideris - Et - Al. - At-Risk - World - Heritage PDFThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Abstracts of The Phokis ConferenceDocument24 pagesAbstracts of The Phokis ConferenceThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Late La Tène bronze jug from the chariot tomb of VernaDocument11 pagesLate La Tène bronze jug from the chariot tomb of VernaThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 47zaykov Et Al PDFDocument5 pages47zaykov Et Al PDFThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Oliver 1965 TwoHoardsOfRomanRepublicanSilver MMAB 23 No 5 January 1965Document24 pagesOliver 1965 TwoHoardsOfRomanRepublicanSilver MMAB 23 No 5 January 1965Thanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- 2016 Sideris A Lydian Silver Amphora With Zoomorphic Handles Ondrejova Volume Studia HercyniaDocument13 pages2016 Sideris A Lydian Silver Amphora With Zoomorphic Handles Ondrejova Volume Studia HercyniaThanos Sideris100% (1)

- ScythiansFromCentralAsianPerspective 2010 AWEDocument22 pagesScythiansFromCentralAsianPerspective 2010 AWEThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- List of Abbreviations For Journals, Series, Lexika and °frequently Cited WorksDocument49 pagesList of Abbreviations For Journals, Series, Lexika and °frequently Cited WorksThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Luminescence Dating of Stone Wall Tomb A PDFDocument10 pagesLuminescence Dating of Stone Wall Tomb A PDFThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Arch Delt 22 1967Document503 pagesArch Delt 22 1967Thanos Sideris100% (2)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 2016 Sideris A Lydian Silver Amphora With Zoomorphic Handles Ondrejova Volume Studia HercyniaDocument13 pages2016 Sideris A Lydian Silver Amphora With Zoomorphic Handles Ondrejova Volume Studia HercyniaThanos Sideris100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- 47zaykov Et AlDocument5 pages47zaykov Et AlThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Original SRC Images Live 2014-09 15 S-21927-0-3Document128 pagesOriginal SRC Images Live 2014-09 15 S-21927-0-3Thanos Sideris100% (1)

- Hill Hespria AgainOnMetalReliefsDocument3 pagesHill Hespria AgainOnMetalReliefsThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Rabadjiev 1995 Heracles Psychopompos in ThraceDocument9 pagesRabadjiev 1995 Heracles Psychopompos in ThraceThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Asypalaia - Cemetries - 5 20 1 PBDocument5 pagesAsypalaia - Cemetries - 5 20 1 PBThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Ure BoeotianPotteryFromAthenianAgoraDocument12 pagesUre BoeotianPotteryFromAthenianAgoraThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Astypalaia Cemetries2 141 716 1 PBDocument3 pagesAstypalaia Cemetries2 141 716 1 PBThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Bouzek ControversiesInAegeanChronology BlgoevgradDocument7 pagesBouzek ControversiesInAegeanChronology BlgoevgradThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Azoulay Exchange As EntrapmentDocument15 pagesAzoulay Exchange As EntrapmentThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Azoulay Exchange As EntrapmentDocument15 pagesAzoulay Exchange As EntrapmentThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Analysis - Technical-La Niece and CowellDocument10 pagesAnalysis - Technical-La Niece and CowellThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Aegaeum MetronDocument7 pagesAegaeum MetronThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Hill Hespria AgainOnMetalReliefsDocument3 pagesHill Hespria AgainOnMetalReliefsThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Ancient Roman Length and Weight MeasuresDocument6 pagesAncient Roman Length and Weight MeasuresThanos SiderisNo ratings yet

- Comedogenic IngredientsDocument2 pagesComedogenic IngredientsMAS, GardinNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Fitocenološka Analiza Mezofilnih Šuma Pitomog KESTENA (Castanea Sativa Mill.) U OKOLINI KOSTAJNICE (Bosna I Hercegovina)Document20 pagesFitocenološka Analiza Mezofilnih Šuma Pitomog KESTENA (Castanea Sativa Mill.) U OKOLINI KOSTAJNICE (Bosna I Hercegovina)Jaroslav BiresNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Inspection and Permit To Transport Copra/Coco Shell/Charcoal For Domestic MovementDocument6 pagesCertificate of Inspection and Permit To Transport Copra/Coco Shell/Charcoal For Domestic MovementJOBETH PIORENo ratings yet

- Pure Saffron, Salajeet and Olive Oil ProductsDocument14 pagesPure Saffron, Salajeet and Olive Oil ProductsHaramain FoodsNo ratings yet

- FOSFA heating recommendationsDocument1 pageFOSFA heating recommendationsAoc Sidomulyo100% (1)

- Basics of Wild Harvested Mushroom IdentificationDocument33 pagesBasics of Wild Harvested Mushroom IdentificationSteve BraganNo ratings yet

- TOTAL KARACHI TO PESHAWAR SHIPMENT DETAILSDocument8 pagesTOTAL KARACHI TO PESHAWAR SHIPMENT DETAILSNisar KhanNo ratings yet

- BIBLIOGRAFIASDocument7 pagesBIBLIOGRAFIASReynaldo Rodas GuizadoNo ratings yet

- Poram Standard Specifications For Processed Palm Oil PDFDocument2 pagesPoram Standard Specifications For Processed Palm Oil PDFlaboratory ITSI50% (2)

- Categorias CencoDocument7 pagesCategorias Cencoeduar martinezNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- PAKISTAN EDIBLE OIL INDUSTRY SWOTDocument1 pagePAKISTAN EDIBLE OIL INDUSTRY SWOTammadNo ratings yet

- Shiva Mushroom Farm Spawn Centre PDFDocument6 pagesShiva Mushroom Farm Spawn Centre PDFMahesh NaikNo ratings yet

- Essential Oil Product ListDocument1 pageEssential Oil Product Listfarrukh baigNo ratings yet

- List of Vegetable Oils PDFDocument20 pagesList of Vegetable Oils PDFtechdocu75% (4)

- Kualitas Minyak Blend Kelapa Kopra Dan Minyak Kelapa Sawit Ditinjau Dari Kadar Air, Kadar Asam Lemak Bebas Dan Bilangan PeroksidaDocument8 pagesKualitas Minyak Blend Kelapa Kopra Dan Minyak Kelapa Sawit Ditinjau Dari Kadar Air, Kadar Asam Lemak Bebas Dan Bilangan PeroksidaesiNo ratings yet

- Datasur: DIA MES ANO Aduana Numero de Aceptacion RUT Digito Verificador Rut ImportadorDocument32 pagesDatasur: DIA MES ANO Aduana Numero de Aceptacion RUT Digito Verificador Rut ImportadorJaime HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Alpine Marine Services (PVT.) Limited: SR. # Vessel Name Berth Date Load Port Discharge Port Product Name Seller NameDocument12 pagesAlpine Marine Services (PVT.) Limited: SR. # Vessel Name Berth Date Load Port Discharge Port Product Name Seller NameUsman MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Masina Manuala de Facut Ulei in CasaDocument3 pagesMasina Manuala de Facut Ulei in CasaSilvia IonescuNo ratings yet

- 2017 Summary of Copra Meal / Copra Cake SupplierDocument2 pages2017 Summary of Copra Meal / Copra Cake SupplierGiovani Francisco FenolNo ratings yet

- Mushrooming Without Fear by Alexander SchwabDocument162 pagesMushrooming Without Fear by Alexander Schwabkastaniani92% (13)

- 4537 9055 1 PBDocument17 pages4537 9055 1 PBAdeliaNantasyaNo ratings yet

- Sawit 2023Document57 pagesSawit 2023Rt SaragihNo ratings yet

- General Mills Mill List H2 List March 2022Document29 pagesGeneral Mills Mill List H2 List March 2022IshakNo ratings yet

- CartãoDocument6 pagesCartãoAna MartinsNo ratings yet

- PT Sinar Alam Permai Traceability SummaryDocument2 pagesPT Sinar Alam Permai Traceability SummaryIhsan AdityaNo ratings yet

- Data Pabrik Kelapa Sawit (Kalbar)Document1 pageData Pabrik Kelapa Sawit (Kalbar)Global Asia BersamaNo ratings yet

- Omega 3 and 6 in Fats Oils Nuts Seeds Meat and Seafood 2Document3 pagesOmega 3 and 6 in Fats Oils Nuts Seeds Meat and Seafood 2Arhip CojocNo ratings yet

- Dry Fruits & NutsDocument3 pagesDry Fruits & NutsSwra GhelaniNo ratings yet

- Farm Sourced Premium Nuts, Dried Fruits & SpicesDocument4 pagesFarm Sourced Premium Nuts, Dried Fruits & Spicestanisha satijaNo ratings yet

- Juglans Regia (Akhrot) Extracts SupplierDocument2 pagesJuglans Regia (Akhrot) Extracts Supplierherbl3926No ratings yet

- The Dude Diet: Clean(ish) Food for People Who Like to Eat DirtyFrom EverandThe Dude Diet: Clean(ish) Food for People Who Like to Eat DirtyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Pasta, Pretty Please: A Vibrant Approach to Handmade NoodlesFrom EverandPasta, Pretty Please: A Vibrant Approach to Handmade NoodlesNo ratings yet

- Plant Based Main Dishes Recipes: Beginner’s Cookbook to Healthy Plant-Based EatingFrom EverandPlant Based Main Dishes Recipes: Beginner’s Cookbook to Healthy Plant-Based EatingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Not That Fancy: Simple Lessons on Living, Loving, Eating, and Dusting Off Your BootsFrom EverandNot That Fancy: Simple Lessons on Living, Loving, Eating, and Dusting Off Your BootsNo ratings yet

- Saved By Soup: More Than 100 Delicious Low-Fat Soups To Eat And Enjoy Every DayFrom EverandSaved By Soup: More Than 100 Delicious Low-Fat Soups To Eat And Enjoy Every DayRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)