Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gambling Reprint Jan2005

Uploaded by

Albuquerque JournalCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gambling Reprint Jan2005

Uploaded by

Albuquerque JournalCopyright:

Available Formats

Reprint of The Big Bet, an eight-part series on gambling in New Mexico,

originally published in the Albuquerque Journal on Jan. 2-9, 2005.

THE SUNDAY JOURNAL

HOME-OWNED

AND

125TH YEAR, NO. 2

HOME-OPERATED

466 PAGES

IN

MADE

IN THE

FINAL

U.S.A.

SUNDAY MORNING, JANUARY 2, 2005

41 SECTIONS

PART 1

Copyright 2005, Journal Publishing Co.

$1

THE BIG BET

JUDGING THE BIG BET

From small change to billions, gambling has exploded in New Mexico over past decade

The first state-tribal agreements to legalize

Indian casinos were signed 10 years ago next

month. New Mexico has now had slot machines

at horse-racing tracks for more than five years.

In the eight-day series The Big Bet, the Journal looks at the gambling industry in New Mexico and how it affects our pocketbooks, our

neighbors and our communities.

BY COLLEEN HEILD

Journal Investigative Reporter

ohn Doe loves to gamble and, boy, does he

have a lot of choices in New Mexico.

He can play Las Vegas-style slots, blackjack and poker at 15 Indian casinos, buy lottery tickets at 1,100 outlets, play the ponies and

slots at five racetracks or gamble at more than

60 veterans and fraternal clubs.

Altogether, an estimated $3.9 billion will be

wagered this year at New Mexico casinos, racinos and clubs and on the state lottery.

It is a remarkable change from a decade ago

when New Mexico gambling was mostly bingo

halls, struggling racetracks and some fledgling

Indian casinos operating outside the law.

First came the creation of a state-run lottery

in 1995.

Then, on the slimmest of votes, lawmakers

legalized casino gambling on Indian lands, thus

changing New Mexicos economic, political and

cultural horizon.

To level the playing field, the Legislature

permitted racetracks to install slot machines.

A decade ago, just eight tribes operated casinos, with a total of about 1,800 slot machines

and a net win of about $150 million a year.

At the states four racetracks, attendance and

betting were down and track owners warned of

layoffs and possible closures.

Today, New Mexicos gambling industry

tribal and non-Indian is flourishing.

As always, the house wins in the long run.

Gamblers in New Mexico are projected to

lose nearly $850 million this year in a state

that for the past decade has ranked among the

poorest in the nation for personal per-capita

income.

See BETTING on PAGE 2

JOURNAL PHOTOS

GAMING TRIBES CASH IN

With Las Vegas-style Indian casinos, a state Lottery and horseracing with slot machines, New Mexico offers plenty of gambling choices.

SERIES AT A GLANCE

PART 1

Part 2

Page 1

n estimated

$3.9 billion will

be wagered this

year on the state

Lottery, racetracks, clubs and

at Indian casinos. Some Indian

tribes with gambling are among

the biggest winners.

Page 5

tate Lottery

sales have

grown every year

since its creation

in 1996. Evidence is mixed

on whether lowincome residents

wager more than

others. Lottery

profits have funded college scholarships for more

than 32,000 people.

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Part 7

Part 8

Page 7

Page 9

Page 11

Page 14

Page 16

Page 18

ew Mexicos

racing and

casino barons

are a varied lot.

One lives in

Greece; another

once sold Fuller

brushes in

Kansas. A partowner of two

tracks is a close

friend of Gov. Bill

Richardson and a

relative newcomer to politics.

he response to

problem gambling in New Mexico has been

uneven, incomplete and uncoordinated. Most

money to

address the problem goes to a

group whose

executive director

earns $125,000

a year and has

financial interests in two racetracks and casinos.

here have

been both economic winners

and losers since

gambling exploded in the state.

There are new

jobs, entertainment and commerce, but more

bankruptcies and

increased need

for police and

emergency services. Meanwhile, the state

has made no

serious effort to

assess the economic impact.

lot machines

have subsidized a sagging

horse-racing

industry. Slot

play began in

1999 at tracks,

and nearly $118

million in slot revenues has gone

to fatten race

purses. About 60

veterans and fraternal clubs also

operate slots

today.

PAGE 3

tate gaming

regulators

wont say what

they do to oversee Indian casinos. Its secret.

But regulators

arent shy in

policing the racetracks with casinos or others

who may run

afoul of state

gaming laws.

ore gambling

could be in

the cards for New

Mexico. Five

more Indian

tribes have taken

steps toward getting into the casino business, and

three more towns

have been mentioned as possible sites for racetracks with casinos.

ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL

RICHARD PIPES/JOURNAL

New Mexicos newest racino, the Black Gold Casino at Zia Park, pictured here on the day before its November opening in Hobbs, will combine live horseracing with 600 slot machines.

Betting Billions on Gambling

from PAGE 1

A host of unknowns

There are some things we

know about gambling in New

Mexico.

For starters, it has helped

some Indian tribes that were

desperately poor. Indian casinos and racetracks employ

more than 10,000 people, and

gambling generates tens of

millions of dollars for the state

treasury as well as for scholarships for thousands of students

at New Mexico universities.

But there are some things

we dont know, perhaps

because we dont want to.

There has been no serious,

independent attempt in recent

years to gauge Indian gamblings economic impact off

the reservations.

There has been no real

state study on problem gamblers since the mid-1990s.

There is anecdotal evidence of

foreclosures, bankruptcies,

divorce and even suicide. How

do the benefits measure up

against the social costs?

There is no way for the

public to know what, if any,

state regulation of tribal gaming is occurring. The process

is cloaked in secrecy.

Does the gambling lobby,

flush with money, wield too

much influence in Santa Fe?

Does the Lottery have a

disproportionate impact on

New Mexicos poor?

Should millions of dollars

from the states take of slot

machines at the

racetrack/casinos be used to

prop up the racing industry, or

should more go to needs like

teacher pay and police?

Former Gov. Gary Johnson,

who signed the historic gambling legislation in the 1990s,

said that under federal law he

had no choice but to negotiate

with the Indian tribes and

pueblos to expand gaming.

Is it good for New Mexico?

I think at best you can call it a

wash because, of course, there

are lot of people adversely

affected by gambling. But

then, on the positive side, its

good for tribes and pueblos,

Johnson said.

Others have a more negative

assessment.

I suspect if one took a poll

in New Mexico by and

large, the Lottery would be

very popular and gaming

would probably have the

majority of citizen support,

said former Democratic Gov.

Toney Anaya.

But we are not Nevada, and

we cant have our economy

based on gambling. But

because we dont have a lot of

other economic development

in the state, were eating ourselves up from inside.

The next wave

There may be more to come.

New racinos the term

used for racetracks with slot

machines are being discussed in Santa Fe, as well as

Tucumcari and Raton. The two

Eastern New Mexico areas

could use an economic shot in

the arm and racino supporters

hope to draw money from

neighboring states and travel-

ers on the interstates.

Santa Fe art dealer Jerry

Peters and Jemez Pueblo are

proposing an off-reservation

casino along the Interstate 10

corridor between Las Cruces

and El Paso. The Fort Sill Oklahoma Apache tribe is interested in the same area, and there

were reports that Picuris

Pueblo was, too. Any of these

would mark the first foray by

a tribe into off-reservation

gaming.

Lottery supporters may

renew a push to boost sales by

adding keno.

Rumors are afloat that

state compacts regulating

Indian gaming will be renegotiated, with some tribes hoping

to offer complimentary hotel

rooms and other incentives to

some gamblers.

There is concern about the

tribes use of a new class of

gambling machines that would

reduce the states revenue

from tribal casinos.

And, some legislators are

talking about opening the regulation gates even wider as a

way to level the playing field.

The attitude is, Why not

just let everybody have at it?

and then we (the state) can get

more revenues from it, or at

least not create a special

class, said one state official.

Keep it under control

Albuquerque attorney Paul

Bardacke represented former

Gov. Bruce King in fighting

efforts by the tribes to legalize

gaming in the late 1980s and

early 1990s.

Now he represents Gov. Bill

Richardson in compact-related

talks with the tribes.

Bardacke said expansion of

gambling wasnt inevitable

under federal law. He said the

state, under King, had prevailed on its legal arguments

in court battles to keep gaming

at bay.

Bardacke said Richardson

inherited wide-open gaming

throughout the state of New

Mexico, when he took office

in 2003.

My efforts on behalf of

Gov. Richardson have been to

try to keep it under control, to

keep it from proliferating to

the extent that its unworkable

for the state, and the Indian

tribes and the non-Indian gaming entities, Bardacke said.

Not surprisingly, King said

he doesnt believe gaming has

changed the state for the better.

I tried to tell everybody

that we better not go with all

that gaming, he said recently.

You cant deny the jobs (it has

created) but I think theres

other ways to create jobs is my

feeling. The other problem is

where they get to have entirely too much influence in policy.

After 40 years in public service, King lost his final re-election bid in 1994 to the pro-gaming Johnson.

I spent a long time trying to

show progressive government

and I didnt want to be the one

who brought gaming to New

Mexico, King said.

Johnsons election campaign

received more than $244,000

from gaming tribes. But he

said recently his decision to

sign the compacts had nothing

to do with the contributions.

From day one, when I started running for governor, I said

I would sign off on compacts,

Johnson said.

A better life

While many of the benefits

and liabilities of gambling can

be debated, it has without

question improved living conditions for some of New Mexicos Native Americans.

Today, 13 tribes operate casi-

nos in New Mexico several

offering more than one location. Five more tribes may

jump in over the next few

years.

Our casinos are going to be

bigger and better, said Charlie Dorame, chairman of the

New Mexico Indian Gaming

Association.

Gaming tribes are trying to

find ways to keep up with the

competition and become destination resorts to attract out-ofstate gamblers and their money.

Despite the economic

progress on Indian lands,

experts say there is still a long

way to go.

This is still an incredibly

poor population. ... Gaming is

not going to solve all of their

underlying problems, said

William Evans, a University of

Maryland economics professor

studying the economic impact

of Indian gaming nationwide.

Dorame said members of

gaming tribes arent interested

in getting rich; they want to

improve their communities.

For instance, 80 percent of

the money for Tesuques Head

Start program comes from

casino revenue, said Dorame,

former governor of Tesuque

pueblo and head of the

pueblos government relations.

Were living in the same old

mud and adobe homes but they

have new roofs.

Two months ago the basketball court at the pueblo consisted of a concrete slab with

two goals, Dorame said. The

other night I played basketball

with my sons in the new

$5 million intergenerational

center.

I finally have a two-car

family, he added, but I still

have a one-car garage.

widespread gambling was neither speedy nor direct.

It essentially began in 1988

when Congress passed and

President Reagan signed legislation to permit Indian casinos.

In the years that followed,

there were federal and state

lawsuits in New Mexico, votes

and re-votes in the Legislature.

What may have been the

most dramatic moment

occurred at 3:12 p.m. on Friday, March 21, 1997.

Reversing a vote from just a

day before, the House voted

35-34 to approve state-tribal

compacts to permit Indian

casinos.

The House-approved legislation also legalized slotmachine gambling at horseracing tracks and veterans and

fraternal clubs.

The reversal came when

Rep. Debbie Rodella, a Democrat from San Juan Pueblo

near Espaola, changed her

vote from no to yes.

Rodella, who was a major

recipient of campaign contributions from gambling interests, said at the time the donations had nothing to do with

her change and that she was

swayed in part by the promise

of Indian casinos bringing jobs

to her district.

I stand firmly by my decision to vote for gaming and

expect my friends and neighbors to accept it and move

towards what benefits us all,

she said at the time.

Contacted recently, Rodella

said she was too busy to comment.

The House had long been the

roadblock to gambling legislation in the Legislature. The

Senate quickly approved the

House-passed bill and Johnson

signed it soon after.

Change in direction

Smoothing the road

New Mexicos journey to

Tribes in New Mexico first

began asking the state to negotiate compacts in 1989, but

were rebuffed.

Some moved ahead anyway.

And by late 1994, there were

eight Indian casinos operating

slot machines in violation of

federal law.

After taking office in 1995,

Johnson wasted no time in

negotiating what were the

original compacts to permit

Las Vegas-style gaming on

Indian lands in New Mexico.

Those compacts were later

ruled unconstitutional by the

state Supreme Court because

the Legislature hadnt given

consent.

Bernalillo County Attorney

Tito Chavez, a Albuquerque

state senator in 1995, recalled

that many legislators believed

some form of gaming expansion was inevitable.

We went to see how other

states were doing it, and the

advice we got everywhere,

everywhere, was Start slowly,

do one thing at a time. Then

BOOM, Governor Johnson

signed that thing and it was all

off and running around the

track. It was just stunning. It

was gone, all at once.

Some say the prospect of a

state lottery helped smooth the

rough road that previously had

prevented other gambling

expansion.

Voters approved a constitutional amendment creating a

state-run lottery in November

1994 but the state Supreme

Court invalidated that vote

because the lottery issue had

been coupled with a ballot

question about video gambling.

The Legislature passed a bill

in 1995 to make the lottery

legal and Johnson signed it.

Then Johnson was off to

court for a fight over his Indian gaming compacts. The U.S.

Justice Department stepped

in, advising tribes with casinos

to close them or face legal

action to seize their slot

machines.

The department, through

U.S. Attorney John Kelly, followed through on the threat

and eventually forced the temporary closure of one Indian

casino.

The legal cloud lifts

PHOTOS BY MARLA BROSE/JOURNAL

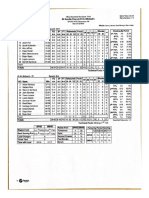

BY THE NUMBERS

$58.5 million

$150 million

$877.5 million

$2.9 billion

Projected amount players

will gamble on slot machines

at veterans and fraternal

clubs this budget year.

Projected amount

players will gamble on the

state lottery.

Projected amount

players will gamble on slots

at racetracks.

Projected amount players

will gamble on slots at

Indian casinos.

Note: Projections are based on players winning back 80 percent of amount wagered on slots and $79.5 million in Lottery prizes

Source: New Mexico Gaming Control Board

That set the stage for the

Legislatures vote in March

1997 to approve new state-tribal compacts for Indian casinos

and slots at tracks and clubs.

The compacts allowed tribal

casinos to begin banking table

games, from blackjack to

craps. They had become fullservice gambling halls.

With the legal cloud no

longer over their heads, tribes

also found it easier and cheaper to borrow money for expansion and casino-related developments like golf courses and

hotels.

The compacts passed in 1997

required tribes to pay the state

16 percent of the take from

their slot machines in

exchange for limited competition from off-reservation gambling.

Tribes eventually won new

compacts that require them to

See NEW MEXICANS

on PAGE 4

ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL

Gaming Tribes Cash In

Several use casino profits to boost education, improve quality of life

BY MIKE GALLAGHER

Journal Investigative Reporter

visitor to a pueblo ceremonial

dance 32 years ago would

have found communal water

spigots, dilapidated buildings

and outhouses.

Tourists sometimes called it

quaint.

Quaint might be picturesque

but it doesnt supply clean water

for children to drink. The correct

word was poverty.

Three decades ago, most New

Mexico pueblos relied on natural

resource leases, federal money and

tourist dollars spent at seasonal

ceremonial dances.

Per-capita incomes were among

the lowest in the United States.

Unemployment rates in some cases

approached 70 percent.

Thanks to gambling, that landscape is changing.

The millions of dollars flowing

through tribal casinos are building

sewer and water systems, new

schools, medical clinics and new

homes for New Mexicos gaming

tribes.

New Mexico Indian Gaming

Association chairman Charlie

Dorame said his pueblo, Tesuque,

has spent more than $20 million in

casino profits in the last few years

on infrastructure.

Thats more money than we

received from the federal government since 1976, he said.

Gov. Leonard Armijo of Santa

Ana Pueblo said the infrastructure

spending is essential.

You cant have economic development without a modern water

system, he said. You cant attract

businesses without infrastructure.

Not all the new tribal economic

infrastructure is hidden below

ground.

Sandia is building a new resort

hotel and golf course, joining Santa

Ana, which has the Tamaya resort;

and Mescalero tore down the Inn of

the Mountain Gods and is building

a 211-room luxury hotel and a larger casino with 1,000 slot machines.

Gaming also has made it possible

for tribes to spend millions to hire

high-powered law firms and lobbyists to pursue various economic

and legal agendas important to the

pueblos, as well as some investment strategies that have turned

controversial.

In addition to a desperate economic situation before Indian gaming, the underlying cultural values

were also in danger.

People were leaving the insulated

and religious pueblo life for the

military and for government jobs

in Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Fewer were fluent in their native

tongue. Skills like weaving and pottery-making for religious ceremonies were dying out as older

tribal members passed away.

A few years ago, only Sandia

Pueblo members over the age of 50

knew how to speak Tiwa, their

native language. At Santa Ana

Pueblo, the cutoff age for speaking

Keres was 48.

Now, native language classes

begin in preschool at both pueblos.

Our language was dying, said

ROBERTO E. ROSALES/JOURNAL

Two-year-old Andrea Chavez ponders her next move in designing a hat at Sandia Pueblos Head Start Program. Andrea and her fellow students will

be moving into a new building, paid for in part with casino profits.

Sandia Pueblo Gov. Stuwart

Paisano. Now 100 percent of our

children are being taught our

native tongue.

No direct distribution

A common misperception of Indian gaming is that casino profits are

distributed directly to tribal members.

That doesnt happen in New Mexico.

To distribute casino profits to

individual members, gaming tribes

would have to pass a law authorizing and explaining the distribution.

Then the tribe would need approval

from the Department of the Interior.

New Mexico tribes have not gone

that route.

The (Sandia) Councils main

focus is on the community,

Paisano said. There are a lot of

associated social problems that just

get worse when you hand out

cash.

Santa Ana Gov. Armijo said, We

dont want to make our people

dependent on gaming money.

Dorame said handing out money

really isnt the pueblo way.

We dont weigh success by the

amount of money people have in

their pocket. It is the success of the

community that matters.

Every pueblo leader the Journal

interviewed said the tribal government views casino profits like a

city or town would view gross

receipts and property taxes.

I think this attitude stems from

basic values, Paisano said. The

Council always goes back to what

is important culture, language

and religion.

Albuquerque Mayor Martin

Chvez was an outspoken opponent

of legalizing gaming, including

Indian casinos.

Ive come to accept the reality

that gaming isnt going away,

Chvez said. But what has

impressed me the most is the

sophistication the pueblos have

shown in handling the money.

Home improvement

Ask a tribal leader about what

the tribe has done with casino profits and invariably they start talking

about sewer hookups.

We have a crisis with groundwater contamination in this valley,

said Ron Lovato, San Juan Pueblos

development director. We are

working on it. We have 95 percent

of the homes hooked into the sewer

system.

San Juan is a medium-sized

pueblo with more than 700 homes

now hooked up to the sewer system.

At Sandia, the hookup rate is at

98 percent, Paisano said.

Replacing septic tanks with sewer systems is an expensive undertaking.

Running sewer lines to a residence can cost between $10,000

and $15,000. Hooking the home up

to the sewer line can cost more

than $1,200.

See GAMING on PAGE 4

ROBERTO E. ROSALES/JOURNAL

Indian Health Services pharmacist Dineyazhe-Toya

counts pills at Sandia Pueblos new health care facility.

Modern medical clinics have been built at Isleta, Sandia, Mescalero and other reservations using profits

from casino gaming.

PAT VASQUEZ-CUNNINGHAM/JOURNAL

JoAnna Garcia, 23, of Santa Ana Pueblo weaves a belt

for a traditional dance during a tapestry-and-weaving

class at the pueblo. Casino gaming has allowed

expanded programs in traditional pottery, weaving and

language.

ROBERTO E. ROSALES/JOURNAL

Saint Antonio de Padua Catholic Church at Sandia Pueblo is framed by the Sandia Mountains. Both the church and the mountains play important roles in the pueblos religious practices. The $2.3

million church, paid for in part with gaming revenues, was completed in 2002 and can seat 500, more than the tribes 480-member enrollment.

ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL

Gaming Tribes Cash In

Pueblo, said, We developed the

Hyatt Tamaya resort and opened it.

Then the attacks of 9/11 took place

and we took a $1 million loss, but it

has bounced back.

Sandoval County recently helped

the tribe restructure and lower

interest rates on its resort debt by

providing conduit financing for

more than $60 million in bonds.

Right now 90 percent of the

tribal budget comes from gaming.

Thats our budget, Ortiz said.

The tribe is trying to move

beyond that.

from PAGE 3

Those costs dont include wastewater treatment.

Local governments normally

issue bonds to fund water systems,

a method that until gaming was

unavailable to tribes because they

lacked the long-term revenues

used to pay off the bonds.

We pay cash, Lovato said.

Sewer systems werent the only

infrastructure missing from tribal

lands.

There were no road departments. No parks and recreation

departments. No trash collection,

Lovato said. We are in fact building from scratch. The casino funded the trash transfer station.

Tesuques Dorame said, I think

the Indian Gaming Compacts are

too short. We are 20 to 30 years

away from building all the necessary infrastructure.

Tesuque, Dorame said, needs 110

new homes but federal money for

housing on the pueblo amounts to

about $150,000 a year.

We are pumping in the rest, he

said.

At Santa Ana and Sandia pueblos,

the housing programs are producing new homes after each tribe set

up a mortgage program.

Sandias operates like a traditional mortgage but with zero interest.

Santa Anas housing program uses

life insurance annuities to reduce a

monthly mortgage payment on a

$100,000 home to $250.

Banks wouldnt loan money for

homes on tribal lands because they

couldnt foreclose, Paisano said.

We used casino profits to create a

mortgage fund that tribal members can tap into after a local bank

reviews their qualifications.

Young people left the pueblo

because they had to live with mom

and dad, Paisano said. Now we

have a new housing program and

people are coming back.

Seeking to diversify

Many tribes have been taking

their own advice and are trying to

expand their economic base.

Unemployment rates on Indian

lands nationally run between 45

and 55 percent.

Six of the gaming pueblos Sandia, Isleta, Santa Ana, Taos, San

Juan and Pojoaque have unemployment rates in the single digits.

Sandia Pueblo has an unemployment rate of 1 percent, according

to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The success isnt uniform. Gaming tribes such as Mescalero and

Jicarilla have unemployment rates

of 44 and 33 percent respectively,

according to the same BIA report.

Recovering lands

ROBERTO E. ROSALES/JOURNAL

Lucy Gutierrez, left, and Jennie Holmes are trying to save the Tiwa language at Sandia Pueblo. The language instructors have helped develop

an alphabet and are working on a dictionary. Every school day they teach

Tiwa to even the youngest children.

A 2002 national study found that

tribes with casinos saw a 26 percent increase in Indian employment and the percentage of working poor dropped by 14 percent.

That is a trend tribal leaders

want to continue.

Some Indian casinos are expanding operations to include hotels

and golf courses in the hopes of

expanding the gambling market to

out-of-state and overseas tourists.

Were going to have work closely with the local hotel associations, Dorame said. It will

require partnerships off the reservation to accomplish this.

Mescalero Apache casino is

working on a $2 million advertising

campaign in conjunction with Ruidoso and the Ruidoso Downs horse

track and casino. The tribe will

contribute the bulk of the money,

targeting potential tourists from

Texas.

Santa Ana Pueblo has been courting retail outlets for property set

aside on U.S. 550.

Sandia Pueblo bought the Coronado Airport near I-25 for a hightech industrial park and has plans

for an RV park.

Our council has taken a conservative approach to off-reservation

investments, said Paisano. We

get approached all the time.

San Juan Pueblo is expanding an

airstrip in the Espaola Valley in

hopes of attracting manufacturing

jobs.

Weve met with officials at Los

Alamos Laboratory to try to get

some interest in developing business offshoots in the Espaola Valley, San Juan development direc-

tor Lovato said. Weve been

actively recruiting manufacturers

to the area. We hope the airport

serves as a linchpin to those

efforts.

A rocky transition

Laguna Pueblo has built a grocery store. Many tribes have built

gas stations that pay no state gasoline taxes.

But not all has been smooth. Sandia found itself part of a nationwide story when a Senate committee launched an investigation of a

Washington lobbyist-public relations team that had been paid more

than $45 million by more than a

dozen tribes, including Sandia.

Sandia had hired Jack Abramoff

to lobby for congressional

approval of a land settlement

agreement involving more than

9,000 acres on the west face of the

Sandia Mountains.

Paisano said the tribe was not

satisfied with the firms work and

was upset when it was disclosed

that Abramoff in e-mails had

referred to his Indian clients as

morons, monkeys and losers.

Paisano said, There have been

missteps.

Tribes have found that getting

into new businesses hasnt been a

sure thing.

Santa Ana Pueblo went to court

after a $1 million investment in a

Chinese computer school went

awry.

But the bulk of the tribes economic development efforts have

been in the tourism industry.

Bob Ortiz, a planner at Santa Ana

Tribal leaders stressed the need

to form alliances with non-Indian

governments on issues from the

environment to economic development.

The issue that may bring conflict

is land acquisition.

Like disputes over water rights,

this issue predates Indian gaming.

But casino profits have given

tribes the economic power to buy,

or bring lawsuits for, property that

individual tribes believe was lost

under Spanish, Mexican or United

States rule.

Sandia, Acoma, Taos, Santa Clara

and Isleta have all bought or recovered lands in recent years.

In some cases, the tribes sought

the properties for religious reasons or to protect religious sites, as

in the case of Taos Pueblos purchase of a ranch adjacent to the

Blue Lake property.

Other purchases have been for

economic development reasons,

like Sandias purchase of the Coronado Airport on North I-25.

If the tribes have the property

declared Indian Trust Lands, the

properties come off the tax rolls.

Depending on location, the tribes

can also run into land use, access

and zoning issues.

Sandia concluded a settlement in

2002 with homeowners and the federal government in its attempt to

reclaim the west face of the Sandias. The agreement basically

blocks development, protects

existing homeowners and public

access and secures Sandias access

to the land for religious observances.

Isleta Pueblo, meanwhile, is

seeking to extend its immunity

from civil lawsuits to property it

has acquired off the reservation.

Both the New Mexico Court of

Appeals and Supreme Court have

rejected the pueblos argument,

but the pueblo has asked for it to

be reconsidered.

One tribal leader told the Journal

that land acquisitions for religious

reasons are high on many tribes

priority lists.

He suggested that tribes are

more likely to be willing partners

with local governments on lands

acquired for economic development.

But properties obtained for religious reasons are likely to be

closed off to the general population

and lead to conflict.

Stitching a society

Bricks and mortar are one form

of infrastructure.

Education and health are just as

important.

Among New Mexico tribes, diabetes is considered an epidemic

that leads to heart disease, kidney

failure and amputations.

Nationwide, Native Americans

are twice as likely to develop diabetes than non-Hispanic whites

and amputation rates are three to

four times higher among Indians

than the general population,

according to the American Diabetes Association.

Several tribes have built medical

clinics and wellness centers to

combat health problems like diabetes that have troubled their communities for years.

Isleta Pueblo set up programs to

teach healthy lifestyles to children

and adults in a recreation center

that includes an Olympic-size pool.

The tribe also provides diabetes

education programs and a medical

clinic.

The Mescalero Apache tribe

built a full-service dialysis unit

that serves tribal members and

people in the surrounding community.

Were able to combine Indian

Heath Services and pueblo money

to expand services to include an

herbalist, physical therapist, a

pharmacy, and counselors for substance abuse, Paisano said. Its

worked tremendously.

Many tribes offer college and

high school scholarship programs,

but Sandias starts in the first

grade.

We will pay tuition for any child

on the pueblo to attend any private

school, Paisano said. We also provide transportation. We require a

commitment from the parents that

they will help their children with

homework and the students maintain their grades.

Most tribes now pay most of the

cost of preschool programs, and

have funded programs for the

elderly and teens.

We all look to how all our people

can benefit from this (gaming),

said Santa Anas Armijo.

Where is the benefit to the

tribe, is the first question we ask.

PAT VASQUEZ-CUNNINGHAM/JOURNAL

Two dogs stand guard at Santa Ana Pueblos new housing addition. Before casino gaming, New Mexico tribes relied on federal housing programs. Now tribes are using casino profits to establish

mortgage programs.

New Mexicans Bet Billions on Gambling

from PAGE 2

pay no more than 8 percent of

their slot take.

At least twice in his tenure,

Johnson put the brakes on

expanded gambling.

He refused to permit the

Fort Sill Apache tribe to set up

a casino near Deming in 1999,

and he pre-empted a state Racing Commission vote on a

Hobbs racetrack in late 2002.

Both ventures would have

violated the near-exclusivity

the state promised the gaming

tribes, Johnson said recently.

When a Richardson-appointed state racing commission

finally approved a new track

and casino in Hobbs in 2003,

there was no serious opposition from gaming tribes.

Dorame says that wont happen next time.

Every business

does it

Some opponents who fought

Johnson on Indian gaming a

decade ago are just as vehement on the issue today.

Ive always felt that horse

racing and lotteries were relatively benign compared with

the crack cocaine of gambling,

which is slot machines, said

Albuquerque attorney and former state senator Victor Marshall. And in fact, New Mexico would be much better off if

we went back to where we

were before the casinos, which

is horse racing and the lottery.

But Albuquerque Mayor

Martin Chvez and others

have given up their active

opposition.

Im a pragmatist, Chvez

said. It is here and it is not

going away. The challenge is

to make lemons into lemonade.

Chvez said the tribes are

doing wonderful things with

the money. They are investing

it in the tribes, their people.

They are looking to diversify.

They are investing in health

care, education.

Gaming tribes are also

incredibly sophisticated in

manipulating the levers of

power, Chvez said. They

lobby. They contribute to campaigns. This is not a bad thing;

every business does it.

Chevron, PNM, everyone.

Terri Cole, president of the

Greater Albuquerque Chamber of Commerce, said the

state is facing a complicated

dilemma that began with the

approval of a state-run lottery.

Adds Cole: The genie is out

of the bottle.

Journal investigative reporters

Thomas J. Cole and Michael Gallagher contributed to this report.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

TODAY: Gambling explodes after

New Mexico takes a chance.

DAY TWO: Lottery sales are

booming.

DAY THREE: A slot subsidy

revs up horse racing.

DAY FOUR: Casino baron is a

friend of Gov. Bill Richardson.

DAY FIVE: Problem gamblers are

left largely to chance.

DAY SIX: The economic winners

and losers of gambling.

DAY SEVEN: Regulation, New

Mexico-style: Casinos, hot dogs

and pizza parlors.

DAY EIGHT: Another crossroads.

Find this series on the Web

at abqjournal.com.

ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL

HOME-OWNED

AND

125TH YEAR, NO. 3

HOME-OPERATED

62 PAGES

IN

MADE

IN THE

FINAL

U.S.A.

MONDAY MORNING, JANUARY 3, 2005

5 SECTIONS

PART 2

Copyright 2005, Journal Publishing Co.

Daily 50 cents

THE BIG BET

N.M. Lottery: Chasing the Rainbow

More than half of us play, and evidence suggests the poor have a higher participation rate

Second in a series

A BURST OF TEARS

BY COLLEEN HEILD

Delores Walker

Journal Investigative Reporter

New Mexicans, it seems, love their

lottery.

Every week, thousands of them

take a shot at the American dream

for as little as $1 a ticket.

Ushered in by public demand in

1996, New Mexico Lottery sales

have grown every year, racking up

nearly $1 billion in gross sales and

pumping millions of dollars into

scholarships for New Mexico kids to

go to college.

Nearly 60 percent of the public

plays the lottery here, according to

one study. But whats the current

breakdown on the people spending

all those millions on lottery tickets?

There are no recent studies that

show who is playing todays lottery

and how much they spend.

Lottery officials nationwide insist

the games dont target the poor, and

New Mexico Lottery officials cite a

1999 study here that shows people

who play are spread evenly across

the economic spectrum.

But there is evidence in New Mexico and elsewhere to suggest that a

small number of players account for

a large share of ticket sales; that participation of the poor is disproportionately higher; and that lottery

spending is regressive because poor

people spend a higher percentage of

their income.

Some say the lottery has special

appeal for lower-income people who

hold little hope of rising above their

circumstances.

Its kind of the rainbow of the

poor, says former Republican Gov.

David Cargo, a member of the state

Lottery Commission.

They look out and they see a lottery ticket, and they see a rainbow.

And occasionally they get it.

Cargo said the New Mexico Lottery has paid off in the sense that

we contribute huge amounts of money to scholarships.

But critics say it is still a tax, and

not that efficient. While it funds

scholarships, the money for education only amounts to about 24 cents

per dollar of sales, with the rest

PAT VASQUEZ-CUNNINGHAM/JOURNAL

Cliff Walker figured his wife

had been in an accident when

she burst into the house crying.

Times had been tough since

Walker fell off the roof of their

Roswell home

last March

and nearly

lost his life.

Recuperating

from his second major

surgery in five

months, he

tried to console his wife

WALKER

that morning.

Its okay,

its just the car. We can fix it,

he said.

Do you love me? Delores

Walker blurted out. Do you

love me an awful lot?

Walker tells folks now hes so

glad he said yes.

Delores Walker had just won

the lottery.

Circle K clerk Jim Weeks, center, waits for the Powerball machine to spit out a ticket for a customer. The store,

at 1200 San Pedro NE, was one of the top 10 locations in the state for lottery sales in fiscal year 2003.

going to prizes and expenses.

Yet many who fought the creation

of a state lottery now describe it as

benign.

As opposed to the other forms of

gambling we have in New Mexico,

the lottery is probably the least

onerous in my opinion, the least

harmful to society, said former

Gov. Toney Anaya, who resisted legislative attempts in the 1980s to create a state lottery.

Anaya still believes gaming

including the lottery is bad for

the state.

But if we have to have a lottery,

thank goodness that theres some

good that comes from it.

A good problem

Since the inception of the New

Mexico Lottery, more than half the

proceeds $485 million have

been returned in prizes.

The net profits have paid for

scholarships for more than 32,000

students. Thats more than the combined fall 2004 enrollments of New

Mexico State University, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology and New Mexico Highlands University.

Per-capita lottery sales in New

Mexico have climbed dramatically

from $49 in 1997 to $79.52 in fiscal 2004, according to the North

American Association of State and

Provincial Lotteries.

New Mexico was 32nd per capita

in lottery sales in fiscal year 2004 of

the 40 states that have lotteries.

So far the lottery has generated

enough profit to pay tuition for all

eligible students, but the pressure to

produce more every year isnt lost

on Lottery chief executive Thomas

Shaheen.

The steady growth in lottery sales

has bucked the trend seen in many

states. New Mexicos only the second lottery to have seven years of

sales increases since its inception.

The other is Georgia, one of the

most successful in the country.

Shaheen, who earns $159,500 a

year, was second in command in

Georgia before he took a pay cut to

run New Mexicos lottery.

Certainly this growth cant continue forever, Shaheen said in a

recent interview. Sooner or laters

theres going to be some leveling

off.

The challenge now is meeting the

success of the lottery scholarship

program, he said.

Now its how to keep raising

enough money to pay for it. Its a

good problem to have but its a challenge.

Pulling in the poor

No one can say definitively what

difference, if any, the lottery has

made on the states economy.

New Mexico had the highest

poverty rate in the nation the year

the lottery began. In 2004, U.S. Census figures ranked us 49th.

A 1999 survey on gambling behavior by the University of Chicagos

National Opinion Research Center

showed the poor spend a greater

proportion of their income on the

games than do higher-income players.

The annual lottery expenditure by

a household earning less than

See LOTTERY on PAGE 6

Lottery Pays Off for N.M. College Students

the time and that wasnt what

we promised, Sanchez said.

Its a promise we made to the

people of New Mexico that we

need to keep.

Sanchez, recently elected by

fellow Democrats to the position of Senate majority leader,

said the state needs to better

promote the scholarship program, especially in the school

system.

Ive had so many people

come up to me and tell me that

they are first-generation college students and that without

this lottery scholarship they

would never have been able to

go, Sanchez said.

But program critics

say scholarships should

only go to those in need

BY COLLEEN HEILD

Journal Investigative Reporter

Congratulations, New Mexico lottery players!

The money youve lost playing the lottery has helped

boost state college enrollment

by up to 6 percentage points.

More than 32,000 young people have received $150 million

in Lottery Success Scholarships.

Theres even a $50 million

surplus in the fund.

The concept of the lottery

scholarship program is simple:

Be a New Mexico resident,

enroll in a New Mexico college

and make a 2.5 GPA with a

course load of at least 12 credit hours.

If you do that, the program

pays your tuition.

The intent was simply to

make scholarships available to

every New Mexican who graduated from a New Mexico high

school regardless of where

they came from or who their

parents were, said Sen.

Michael Sanchez, D-Los Lunas.

To me, its the ultimate scholarship because its there for

everyone.

Proponents also say the program is another tool to keep

kids from middle- to upperincome families from leaving

New Mexico for their college

education.

But critics dont like the

merit aspect of the program,

arguing the scholarships

should be based on need.

They point to studies that

show many students who

A regressive system?

COURTESY OF NEW MEXICO LOTTERY AUTHORITY

Lottery success scholarship winner Brooke Brown graduated

from the University of New Mexico in May 2003.

receive the scholarships come

from middle-to-high-income

families and probably would

have gone to college anyway.

Richardsons plan

For every $1 spent on the

New Mexico lottery, about 24

cents is earmarked for lottery

scholarships.

In New Mexico, theres a

move backed by Gov. Bill

Richardson and others to

broaden lottery scholarship

eligibility criteria and change

the way benefits are dispersed.

A separate financial aid fund

would be set up for low-income

students. One proposal would

tap interest earned on the lottery surplus.

The governors plan would

relieve some pressure on the

state-operated lottery to foot

the entire bill for college

tuition which can run up to

$3,700 a year.

Instead, the state would pay

a flat amount based on the university. The change would also

allow families to take advantage of a federal tax credit.

But Sanchez, the legislator

credited for helping launch the

lottery scholarship program in

1997, is reluctant to tinker too

much with what many see as a

major New Mexico success.

Sanchez said a good portion of people who play the

lottery in New Mexico are

aware that the money goes to

education.

To start to change it, or try

to make it a needs-based scholarship, that wasnt the intent at

More than a dozen states,

including New Mexico, have

put their dollars into broadbased merit scholarship programs instead of financial aid

for low-income students.

About half of those fund the

programs from lottery revenue.

That doesnt sit well with

some who say limited government revenue should be spent

where the need is greatest.

Further exacerbating critics concerns is the regressivity of lotteries, which have the

effect of providing scholarships for middle- and upperincome students with lottery

revenues disproportionately

coming from poorer citizens,

says a report earlier this year

by two members of the Tennessee Higher Education Commission.

Unlike other states programs, the New Mexico lottery

scholarship is based on college, rather than high school,

performance.

According to an article in the

Chronicle of Higher Education, 64 percent of scholarship

funds in New Mexico go to students whose families make

$50,000 a year or more, while

only 15 percent of the money

goes to those earning $20,000

or less.

University of New Mexico

economists Melissa Binder and

Philip T. Ganderton report that

academic performance is

closely linked to family

income, so most merit programs will likely disproportionately benefit students from

better-off families.

For every (lottery) scholarship paid to a minority student

at UNM, another scholarship

went to a non-minority student, and for every low-income

scholarship, close to three

more went to students with

higher family incomes,

according to a newly released

study by Binder and Ganderton.

The lottery program requirement that students be enrolled

continuously aims to encourage students to graduate, but

an unintended effect might be

to hurt low-income students

who have trouble enrolling full

time while also working fulltime jobs, the report stated.

The GPA requirement of 2.5

may also disproportionately

affect minority and lowincome students, who are more

likely to be poorly prepared

academically, the UNM economists concluded.

More needy than

before

The Commission on Higher

Education study said funding

for the states need-based

grant program has deteriorated and federal support has

declined over the years, so students have come to rely more

on loans.

As a result, students from

New Mexicos lowest income

families (have been left) more

needy than before the state

Lottery Scholarship was implemented.

Jesse Mathews is a sophomore at Eastern New Mexico

University thanks in part to

the lottery scholarship.

All I had to do was just to

maintain a 2.5 GPA and it hasnt been hard to maintain it at

all, said Mathews, a music

education major who graduated from Carlsbad High School

in Carlsbad.

Along with the free tuition,

he has received other scholarships and a federal Pell Grant

to pay for student fees, his

dormitory room and meals. He

said he still would have gone to

college had he not received a

lottery scholarship.

There were some times in

high school I really considered

dropping out, but college was

always a dream of mine.

After finishing ENMU and

attending graduate school,

Mathews would like to help

revive the music program in

the Carlsbad public school system.

He was aware of the debate

over the lottery scholarship

program.

I would have been eligible

if it had been needs-based,

Mathews said. But I hope

they dont change it. I believe

everybody should be able to

benefit. It really is a blessing

for a lot of people.

ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL

Lottery a Big Draw in Some Poor Areas

from PAGE 5

$10,000 a year was $520, compared to $338 annually for

households with incomes over

$100,000, the survey concluded.

A study commissioned by

the New Mexico Lottery found

that people earning $25,000 a

year or less didnt play the lottery more than other income

groups.

But data from the 2000 U.S.

Census and the New Mexico

Lottery for fiscal year 2004

show the lottery is a powerful

draw in some of the states

poorest counties.

McKinley County, which

had the states lowest per-capita annual income at $9,872,

spent more than $5.6 million

on lottery tickets. That is

about $76 per county resident.

Luna County, the second

poorest with a per-capita

income of $11,218, had lottery

sales of more than $2.4 million

$97.99 per resident.

Guadalupe County, third

poorest, had lottery sales of

more than $1 million $227

per resident.

Cibola County, fourth poorest, had lottery sales of $78.58

per resident.

By contrast, residents of Los

Alamos County, which had the

highest per-capita income with

$34,646, spent $53 apiece on

lottery tickets. In Santa Fe

County, the second wealthiest,

per-capita lottery spending

was $62.46. In Bernalillo County, which had the third highest

per-capita income, annual

sales in 2004 amounted to

about $71.42 per resident.

Lottery officials say some

New Mexico counties had

higher sales because they are

near another state or a major

interstate where tourists or

other out-of-state residents

stop for fuel or other purchases.

A 1996 study by the New

Mexico Department of Health

showed the lottery was the

most popular form of gambling among New Mexicans

surveyed.

Three percent of the callers

to the New Mexico Council on

Problem Gamblings hotline in

the third quarter of 2004 said

playing the lottery was their

favorite type of gambling.

Nearly half the callers said

they played the lottery, with 23

percent saying they often

bought lottery tickets.

A report to the National

Gambling Impact Study Commission in 1999 showed the top

5 percent of players accounted

for 54 percent of the total

sales.

The heaviest lottery players

tend to be middle-aged males

and are nearly twice as likely

as the general population to

lack a high school diploma, the

report said.

A winning reputation

Its a Powerball Wednesday

and the jackpot has climbed to

more $127 million.

Since 1999, John Brooks

Supermart #1 has been in the

top 10 retailers in the state

with the highest overall sales.

More than 1,100 retailers sell

tickets.

The store, at 12th and Cande-

PAT VASQUEZ-CUNNINGHAM/JOURNAL

A clerk keys in an order for a Powerball ticket. Per-capita lottery sales in New Mexico have

climbed from $49 in 1997 to $79.52 in fiscal year 2004.

BY THE NUMBERS

$148 million

$85.2 million

$35.9 million

$27.7 million

N.M. lottery sales

in fiscal year that

ended June 30, 2004

Amount paid out

in prizes (including

free tickets)

Lottery scholarship

fund

Expenses of running

lottery

ODDS OF WINNING

(Approximate odds per $1 of play)

ROADRUNNER CASH

POWERBALL

1 in 278,256

1 in 120,526,770

Odds of winning top prize

Odds of winning jackpot

1 in 66

1 in 36

Overall odds of winning a prize

Overall odds of winning a prize

Source: New Mexico Lottery

HISTORY OF LOTTERIES

c.100-44 B.C.: Form of lotteries dates back to Caesar

100 B.C.: The Hun Dynasty

in China creates keno. Funds

raised by lotteries were used

for defense, primarily to

finance construction of the

Great Wall of China

1700s: Benjamin Franklin

uses lotteries to buy cannons

for Revolutionary War

1878: All states in U.S.

except Louisiana prohibit lotteries, either by statute or

constitution

1964: New Hampshire Legislature creates state lottery,

the first legal lottery in the

United States in the 20th

century. It is tied to horse

races to avoid 70-year-old

federal anti-lottery statutes.

1996: New Mexico Lottery

begins sales

Source: North American Association of State and Provincial Lotteries

laria near downtown Albuquerque, sits just east from a

bingo parlor and across the

street from two package liquor

stores.

This store has sold

$1,255,944 in winning lottery

tickets, a sign at the liquor

department boasts.

Tony Gallegos walks out of

the store clutching only a

Powerball ticket.

Hes a regular lottery player,

but still hasnt struck it rich.

Ive won $4, and $11

before, he said, but I still

have hope.

Because of the stores reputation, people from all over

town head there to buy tickets.

One gentleman came from

the Heights because he looked

us up on the Internet (and saw

our record), a cashier tells a

customer. But you know,

youll win if its your time to

win.

A favorable climate

Lotteries across the country

and the District of Columbia

generated nearly $49 billion in

sales in fiscal year 2004. The

first was created 40 years ago

in New Hampshire.

It took New Mexico decades

to join the crowd.

As far back as the mid-1960s,

New Mexico politicians were

pitching lottery proposals. But

none got very far.

Weve tried these lottery

bills before, State Senate

floor leader Tibo Chavez, DValencia, said in a news story

published in February 1967.

I dont think the people of

New Mexico are ready to

resort to lotteries because of

their moral makeup, he said.

Based on our tradition, based

on our background, there has

never been a great response to

gambling proposals.

Lottery proposals arose

again in the mid-1980s, but

died after drawing criticism

from church groups.

Billed by then-Sen. Manny

Aragon, D-Albuquerque, as a

ticket to boost state government income without raising

taxes, the lottery was characterized by one Republican legislator as a golden octopus

that would create no new

wealth and hurt legitimate

business.

In a letter to then-Gov. Garrey Carruthers, 40 members of

the board of directors of the

New Mexico Conference of

Churches urged him to veto

legislation in 1987 that would

have created a sweepstakes

lottery that tied winning numbers to horse races.

Such a lottery would encourage fantasies of instant wealth,

the letter said. Carruthers ultimately vetoed the measure.

By the 1990s, the political

climate had warmed. A Journal opinion poll, for instance,

showed nearly 65 percent of

those surveyed said the state

should have a lottery.

In 1994, voters approved the

lottery by passing a constitutional amendment. The state

Supreme Court nullified the

vote because the lottery question had been coupled with

another gaming measure on

the ballot, an unconstitutional

practice known as logrolling.

But the Legislature sensed

the swing in public opinion and

months later approved another

lottery measure, which was

signed in 1995 by Republican

Gov. Gary Johnson.

An eye on profits

Initially criticized for excessive operational spending, the

lottery has since cut administrative costs by more than

$3 million annually.

The number of employees

about 62 has stayed the

same while proceeds to state

government have increased 67

percent since the first fiscal

year of operations.

Yet the amount returned to

the state as profits is still less

than 25 cents on the dollar,

compared to a national average about 33 cents.

Shaheen and others say New

Mexicos operational costs are

higher because vendors who

provide online games and other services charge more here

than in other states.

Were going to have higher

vendor fees because we

have a lower volume in sales

and they have to have a profit

margin, Shaheen said.

What the future holds is anyones guess.

With rising gasoline prices,

lottery officials have noted a

decline in sales of instant

scratcher tickets, which tend

to be impulse buys at convenience stores or gas stations

when purchasers have extra

dollars after filling up the gas

tank.

Shaheen said the advent of

legalized Indian gaming also

has had an impact.

Other factors affecting

future sales include the fact

that the state isnt expecting a

major population growth.

And were limited to the

types of games, limited by law

what we can do, he said.

As a result, theres renewed

talk of launching the fastpaced game of keno, which lottery officials once estimated

could add another $4.5 million

a year for education.

A bill to expand the lottery

to keno was rejected by lawmakers in 2001. Opponents

said the game was too addictive.

LIGHTNING STRIKES

Delores

Walker

Part 2

When it came to the

New Mexico lottery,

Delores Walker was no

big spender.

For the past two years,

shed head to the nearby

Circle K store on North

Main Avenue twice a

week and buy a $5

Powerball and a $5

Roadrunner Cash ticket.

For the Aug. 26 drawing, she splurged and

spent $10 on each game.

When Walker returned

to the store the next

morning and presented

her tickets, the cashiers

eyes got big as saucers.

Im going what did I

win, thinking it was like

$500 or something,

Delores Walker recalled.

Maam, you won the

whole thing, the cashier

said.

Youre kidding,

Delores Walker said.

The cashier put the

ticket down in front of

her, showing $290,000 as

the payoff.

Does that help you to

believe? she asked.

The winnings have

allowed Delores Walker

to quit her job of six

years at Desert Motors in

Roswell and care for her

husband.

The Walkers have paid

off medical bills and

bought a new pickup

truck and theres enough

money left so that they

can breathe a little easier about future finances.

With a niece attending

college on a lottery scholarship, she hasnt

stopped betting on the

lottery.

I say, You never

know, lightning could

strike twice.

ABOUT THIS

SERIES

DAY ONE: Gambling explodes

after New Mexico takes a

chance.

TODAY: Lottery sales are

booming.

DAY THREE: A slot subsidy revs

up horse racing.

DAY FOUR: Casino baron is a

friend of Gov. Bill Richardson.

DAY FIVE: Problem gamblers are

left largely to chance.

DAY SIX: The economic winners

and losers of gambling.

DAY SEVEN: Regulation, New

Mexico-style: Casinos, hot dogs

and pizza parlors.

DAY EIGHT: Another crossroads.

Find this series on the Web

at abqjournal.com.

REPORTING THE PROJECT

19-year veteran of the Journal staff, Colleen Heild

joined the investigative team in 1996.

A native of Tucson, she began her career at the

Journal covering federal courts. That led to more indepth reporting on topics such as the fatal shooting

of a Mountainair policeman in 1988 and the states

foster care system.

More recently, Heild assignments have included

reports on convicted sex offenders in New Mexico,

questionable procurement practices by state officials

and the controversial rewidening of N.M. 44, now

U.S. 550.

eff Jones, 35, covers gambling issues for the Journal, including tribal gaming, horse track/casino

operations and the business of horse racing.

Prior to taking over those responsibilities after his

assignment to the state desk in 2003, he covered

the police beat in Albuquerque.

Jones is a 1992 graduate of the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley.

homas J. Cole joined the Journal in 1992 and has

been an investigative reporter since 1996. His work

at the newspaper has won numerous state, regional

and national awards.

Cole, 50, previously worked for The (Santa Fe) New

Mexican and United Press International in Ohio, West

Virginia and Pennsylvania.

He is a native of Ohio and a graduate of the Journalism School at Ohio State University.

HEILD

ike Gallagher has been an investigative reporter for the

Albuquerque Journal since 1986.

A University of New Mexico graduate, Gallagher has been

a reporter in New Mexico since 1976. He has covered a

wide range of issues, including organized crime, political

corruption, drug smuggling, telecommunications, medicine

and state prisons.

His series on illegal and so-called gray area gambling in

the early 1990s was often cited during legislative hearings.

COLE

M

JONES

GALLAGHER

ALBUQUERQUE JOURNAL

HOME-OWNED

HOME-OPERATED

AND

125TH YEAR, NO. 4

50 PAGES

IN

MADE

IN THE

FINAL

U.S.A.

TUESDAY MORNING, JANUARY 4, 2005

5 SECTIONS

PART 3

Copyright 2005, Journal Publishing Co.

Daily 50 cents

THE BIG BET

Slots Keep Ponies Running

Sport of Kings rebounded with creation of racinos and infusion of cash

Third in a series

BY THOMAS J. COLE

Journal Investigative Reporter

magine youre a factory owner.

Lets say you make Hula-Hoops,

but fewer and fewer people want

to buy them because of fading

popularity.

Suppose then that state government, concerned your business may

close and people will lose jobs,

comes up with a plan to subsidize

your factory, making it profitable

for you to keep on making HulaHoops.

Finally, picture this: Over five

years, the subsidy totals nearly $118

million.

A good deal? You bet. And thats

the deal that owners, trainers,

breeders and riders of racehorses

got when New Mexico lawmakers

approved slot machines at tracks.

For every dollar gamblers lose on

the machines, 20 cents goes to subsidize race purses, the cash prizes

awarded based on how a horse finishes.

Horse owners get the biggest

share of the purses, but trainers,

breeders of horses bred in the state

and jockeys also share in the pie.

The state approved slot-machine

gambling at tracks in 1997 and the

gambling began two years later.

There is no dispute that the

machines have been good, even

great, for the horse-racing industry.

From 1998 to 2000, the number of

jobs directly related to the industry

jumped 180 percent, to 10,200,

according to one estimate.

New Mexico has five tracks now

and that number could jump to at

least eight in coming years. There

are more race days, and the amount

of money wagered on races is up.

Slot machines revived a dying

industry, says India Hatch, executive director of the state Racing

Commission.

In 2003, the purse subsidy accounted for 76 percent of all the prize money that went to horse owners and others.

And the money keeps pouring in.

The purse subsidy is projected to

grow more than 19 percent, from

$29.4 million to $35.1 million, in the

fiscal year ending this coming June

30.

But when is a lot of money

enough?

Some of that money now going to

race purses could be used by the

state to better educate children, put

more cops on the road or even prop

up another struggling industry.

Former state Rep. Max Coll, a

Santa Fe Democrat who fought

against slot machines at tracks, says

its time to reassess the purse subsidy.

RICHARD PIPES/JOURNAL

Jockey Ken Tohill, riding Barbarays Claim, left, finishes fourth in a race at Sunland Park. The ex-California jockey says he is making money and having

fun being a part of New Mexicos racing revival.

The question is how much more

will you bite the public for to support the industry, Coll says.

Through June of last year, slot

machine players at tracks and casinos had left behind $589.4 million

the net win for the racinos.

In addition to the 20 percent that

goes to purses, the state gets a 25

percent cut of what gamblers lose,

with the money going into its main

checking account to help pay for

government services.

Track owners keep the other 55

percent, but have to pay operating

expenses for the casinos, including

machine costs and payroll.

Each of the four tracks that operated in 2003 made a profit, according to their financial statements.

Sunland Park, the states most

successful track, reported net

income of $25.8 million, with slot

machines producing 86 percent of

its revenues. Net income for the other tracks ranged from $781,000 to

$2.9 million.

The revival

The racing industry was in trouble in the 1980s and for much of the

90s.

The industry was rocked by alle-

gations of horse drugging and other

corruption in the 80s, and attendance at racing dropped steadily in

the 90s.

The industry repeatedly tried to

convince the Legislature that it

needed slot machines to survive.

It succeeded in March 1997 as

part of a deal that settled a long-running legal dispute over Indian casinos and also put slot machines in

veterans and fraternal clubs.

Rhode Island first introduced

slots at tracks in 1993. West Virginia

followed, and New Mexico is one of

seven states today with racinos.

Three more states have plans to

make the move.

Doug Reed, director of the University of Arizonas Race Track

Industry Program, says, New Mexico was about at the end of its line

when slot-machine gambling began

in 1999.

Now its a respectable mid-level

(quality) type of racing, Reed says.

Some figures:

Horses will race at tracks 281

days in 2005, up from 194 in 1998.

The amount of money wagered

on racing was $153.6 million in 2003,

See RACING on PAGE 8

THE BREEDER

THE JOCKEY

Mac Murray

Ken Tohill

Before New Mexico tracks got slot

machines, Mac Murray and his wife, veterinarian Janis Spencer Murray, had a farm in

Utah to breed racehorses.

Today they operate MJ Farms near Veguita, about 40 miles south of Albuquerque.

It was a simple economic decision to make

the move to New Mexico in 2000.

First, theres more purse money for horse

racing. Second, theres added purse money

for owners and breeders of winning New

Mexico-bred horses. Third, on each day that

it offers racing, a racino must have at least

four races restricted to New Mexico-bred

horses.

You have a chance of owning a racehorse

here and making money, Mac Murray says.

A lot of other places, its just a hobby.

He says New Mexico has probably the

best program in the United States as far as

breeders awards and purse structure.

A survey conducted by the New Mexico

Horse Breeders Association in 2002 found

that MJ Farms was one of 26 breeders to

relocate to New Mexico in the few years

immediately after slot-machine gambling

began at racetracks.

The association says its membership shot

up from 672 in 1998 to 1,247 in late 2004.

MJ Farms is an impressive operation,

spread over 90 acres in the bucolic Rio

Grande bosque. Murray says he and his wife

have invested $2.5 million in the property,

which includes a large home, pens and a

neatly kept barn.

On a day last November, about 140 horses

Horse-racing jockey Ken Tohill was about

to hang up his crop a few years back.

Tohill had been riding for more than two

decades, mostly at Northern California

tracks. Competition was tough and the

pressure to win intense, he says.

The moneys good there but the expenses

are so high for everybody, Tohill says. It

just takes a lot of fun out of it. You cant

make a mistake. You will be replaced.

But in the summer of 2003, a friend convinced Tohill to make a trip to New Mexico

and check out the racing here. He stayed.

People enjoy what they do here and its

fun to be a part of, Tohill says. Everybody

has so much a better outlook on our industry.

Slot machines are responsible for putting

some of the joy back in horse racing in New

Mexico.

Youre running for real money because

of the (track) casinos, Tohill says. Im

making a better living. Its been one of the

better moves Ive made.

Tohill began racing at Albuquerque

Downs but competed last year at all New

Mexico tracks.

At Sunland Parks 2003-04 meet, he won

69 thoroughbred races, tying for first in that

category. He topped all thoroughbred riders

with victories in five stakes races, one with

a purse of nearly $133,000.

Tohill says he grossed about $160,000 last

year, with the major part of that income

coming from racing at Sunland Park. He

GREG SORBER/JOURNAL

Mac Murray says the revival of horse racing

has been good for the industry, as well as for

all of New Mexico.

were on the farm, many of them pregnant

mares.

Murray says he took in an average of just

over $20,000 a horse at a recent sale of 14

quarter horses bred at MJ Farms. His top

stallion takes in about $500,000 a year in

stud fees. The Murrays also race some horses.

There is a trickle-down economic benefit of

having MJ Farms in New Mexico.

Murray says he employs eight to 10 people

full-time, with an annual payroll of $250,000.

The farm also has to buy goods, like feed, fuel

and equipment. Murray says he spends

$300,000 a year just on feed.

You cant believe the (economic) multiplier effect in horse racing, Murray says. It

helps everybody. Its a big boost for the state,

tax dollars. It helps you and me.

Pregnant quarter horse

mares graze

at MJ Farms

near Veguita,

about 40

miles south of

Albuquerque.

Mac and Janis

Spencer Murray moved

their horsebreeding operation from

Utah to New

Mexico to

take advantage of the

rebirth of the

states racing