Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Scourge Returns: Black Lung in Appalachia - Enviro Health Perspectives (Jan 2015)

Uploaded by

AppCitizensLawOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Scourge Returns: Black Lung in Appalachia - Enviro Health Perspectives (Jan 2015)

Uploaded by

AppCitizensLawCopyright:

Available Formats

News | Focus

A Section 508conformant HTML version of this article is

available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.124-A13.

A Scourge Returns

Black Lung in Appalachia

In the early 1970s, coal workers pneumoconiosis, or black lung, affected around one-third of

long-term underground miners. After new dust regulations took effect, rates of black lung plunged.

Today, however, they are once again rising dramatically, and the new generation of black lung patients

have disease that progresses far more rapidly than in the past. Tyler Stableford/Getty

Environmental Health Perspectives volume 124 | number 1 | January 2016

A13

Focus | Black Lung in Appalachia

nce a month, a group of men in t-shirts, jeans, and baseball caps gather

around a long table at the New River Health Clinic. The clinic, a small,

one-story yellow clapboard building, is located in the tiny town of Scarbro,

nestled in the bituminous hills of southern West Virginia. The members of

the Fayette County Black Lung Association greet each other by name while

they pour bitter black coffee into small Styrofoam cups.

Amidst the chatter and the coffee are the coughs. Some of the men hack loudly, others more

quietly. All of them have advanced black lung, a disease they acquired working in the local mines.

Although roughly 22% of underground miners smoke,1 compared with about 18% of U.S. adults

in general,2 none of these men do. They gather not just as a support group but also to help one

another complete the stacks of paperwork necessary to apply for government-mandated benefits for

black lung and navigate the tortuous appeals process.

Aside from the groups leader, a bespectacled septuagenarian named Joe Massie, all the other

members are in their 50s or early 60s. Thats relatively young for someone with advanced black

lung, and other workers are getting sick even earlier. These miners, who have gotten so sick so fast,

are on the forefront of a wave of new black lung cases that are sweeping through Appalachia.

Scientists first noticed a troubling trend in 2005, when national surveillance conducted by

the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) identified regional clusters

of rapidly progressing severe black lung cases, especially in Appalachia.3 These concerns were confirmed in followup studies using a mobile medical unit providing outreach to coal mining areas,4,5

with later research showing that West Virginia was hit particularly hard.6 Between 2000 and 2012,

the prevalence of the most severe form of black lung rose to levels not seen since the 1970s,7 when

modern dust laws were enacted.8

Scarier still, the new generation of black lung patients have disease that in many cases progresses far more rapidly than in previous generations. Today, advanced black lung can be acquired

within as little as 7.510 years of beginning work, says Edward Petsonk, a pulmonologist at West

Virginia University. But not all cases progress so quickly; thus, occupational health researchers fear

that what they are seeing now is only the tip of the iceberg.

The History of Black Lung

Black lung is not a new disease. Ever since humans first started mining coal nearly 5,000 years

ago in Bronze Age China,9 those who worked in the mines breathed in the black dust that,

over time, destroyed their lungs.

Writing in 1846, Scottish physician Archibald Makellar sketched out the course of the disease in miners exposed to extremely high levels of dust: A robust young man, engaged as a miner,

after being for a short time so occupied, becomes affected with cough, inky expectoration, rapidly

decreasing pulse, and general exhaustion. In the course of a few years, he sinks under the disease;

and, on examination of the chest after death, the lungs are found excavated, and several of the cavities filled with a solid or fluid carbonaceous matter.10 Makellar called the disease black phthisis.

Later physicians gave black lung its official modern name of coal workers pneumoconiosis (CWP).

A14

volume

124 | number 1 | January 2016 Environmental Health Perspectives

Focus | Black Lung in Appalachia

The disease starts with dustwhether

swinging picks or using large machines,

the process of breaking up coal and extracting it from its prehistoric home creates

vast amounts of dust. And unless effective

measures are used to control airborne dust

in the narrow underground shafts, miners

can breathe it into their lungs.

Coal mine dust isnt uniform; its a jumble of substances and particle sizes, which

vary in their effects on the lungs.11 Larger

thoracic particles settle in the bronchi,

the main air passages to the lungs.12 The

presence of coal mine dust in the bronchi stimulates the production of mucus,

Petsonk explains, so that people can more

easily cough up the offending particles. Its

an efficient system, but prolonged inhalation of the dust can lead to chronic bronchitis in miners. Coal dust particles are very

reactive, including the chemical bonds on

the surface, Petsonk explains. They will

interact with anything nearby, including the

bodys tissue, which creates an inflammatory response.

Its the smaller respirable dust particles, though, that create the damage most

associated with CWP. Because of their

small sizeoften 2.5 microns or less in

diameterthey can easily travel beyond

the bronchi, into the bronchioles and

alveoli. Any small particle this deep in

the lungs, whether from cigarette smoke,

car exhaust, or coal mine dust, can create irritation in the site where it lands.13

The bodys immune system attacks the

particles, creating inf lammation in the

surrounding region. Although this inflammation can help kill invading pathogens,

it cant remove components of coal mine

dust such as coal and silica, which remain

in place and cause lung tissue damage.

The body then doubles down on its efforts,

which further damages the delicate lung

tissue. The result is chronic inflammation

that ultimately scars the lungs, creating

patches that radiologists can see on X rays

and CT scans.14

Smaller patches of damage may have

relatively little effect on a miners lung function measurements. Over time, however, the

damage becomes more widespread, creating

the 1- to 2-mm nodules of immune and

inf lammatory cells, collagen fibers, and

black dust indicative of so-called simple

CWP.15 Symptoms of simple CWP include

chronic cough, increased phlegm production, and shortness of breath. CWP sufferers also are at increased risk

of emphysema,16 which is an

important cause of morbidity

among miners.17

In some patients, the disease progresses to complicated

CWP, a condition also known

as progressive massive fibrosis

A section of lung shows the ravages of progressive massive fibrosis (PMF). The disease is

characterized by large, dense masses of fibrous tissue that often appear in the upper lungs.

The lung itself can appear black due to the slow buildup of coal dust particles over the years.

Biophoto Associates/Getty

Inset: Highly reactive particles of coal mine dust can infiltrate the deepest reaches of

the lung. These inhaled particles of coal dust and/or silica create a chronic inflammatory

response that damages the lung. Ed Reschke/Getty

Environmental Health Perspectives volume 124 | number 1 | January 2016

(PMF). As its name suggests, PMF is characterized by large, dense masses of fibrous

tissue more than 1 cm in diameter, which

often appear in the upper lungs.18 The lung

itself often appears blackened. The presence of fibrosis impairs the ability of the

lungs to bring oxygen to the blood, which

leaves sufferers chronically short of breath

and may result in death.6

Initially, coal dust itself was seen as

rather harmless, and the true cause of

CWP was believed to be silicosis. This

disease is caused by inhaling particles of

respirable crystalline silica, which also can

be found in coal mine dust.19 Indeed, the

symptoms of CWP overlap with those of

silicosis; the two diseases can look similar on X rays, and both fall within the

constellation known as coal mine dust

lung disease.18,19 However, work begun in

the nineteenth century by Makellar10 and

fellow Scottish physician J.C. Gregory, 20

which continued into the 1920s and 30s,

began to focus specifically on coal dust as

the sole culprit of CWP.21,22 By the 1950s,

scientists had shown with near certainty

that CWP could be caused exclusively by

excessive exposure to coal dust.

This came as no surprise to the tens

of thousands of coal miners working

throughout Appalachia and across the

rest of the country, who for decades had

observed and experienced the devastation

caused by black lung. By the late 1960s,

the crisis had come to a head. In 1968

the members of United Mine Workers of

America went on strike to create better

working conditions, including protection

from coal mine dust, and to set up a fund

for miners disabled by black lung.23

The strike worked. In 1969 Congress

passed the Federal Coal Mine Health and

Safety Act, or Coal Act for short, which

was signed into law by President Richard

Nixon.24 The Coal Act created the agency

that would become the Mine Safety and

Health Administration, and required that

A15

Focus | Black Lung in Appalachia

every underground coal mine be inspected

four times per year and surface mines

twice a year. The Act also set limits on

the amount of dust that miners could be

exposed to and developed procedures for

miners disabled by CWP to receive compensation.

In the early 1970s, shortly after the Coal

Act went into effect, CWP affected around

one-third of miners who had worked underground for more than 25 years.5 As the new

rules and regulations took effect, rates of

CWP began to drop, then plunge. By the

1990s, it seemed CWP was on its way to

becoming a thing of the past.25

Fighting the Dust

Another requirement of the Coal Act was

the creation of the Coal Workers Health

Surveillance Program (CWHSP), a voluntary screening program for black lung in

which miners receive X rays upon hiring

and then can return for followup every

five years thereafter. One of the physicians

responsible for evaluating those X rays was

Petsonk. After the number of miners diagnosed with CWP began to drop in response

to the improved dust standards, 25 Petsonk

expected they would keep dropping

except they didnt. In the early 2000s,

Petsonk believed he was seeing an increase

in the number of PMF cases, but he needed

data to back up his perception.

In 2005 he and other NIOSH investigators published the initial evidence of

geographical clusters of rapidly progressing

cases of CWP, including in Appalachia.3

In 2011 Petsonk and colleagues published

a study of 138 West Virginia miners compensated by the state for PMF between

2000 and 2009. 6 All those miners had

spent their careers in the mines long after

the Coal Act went into effect. The study

thus indicated that either the Coal Act

standards were not adequate or the rules

were not being followed, or both.

The only thing that causes this illness

is the inhalation of dust during coal mining, says David Weissman, director of the

Respiratory Health Division at NIOSH.

To have people getting sick so young, they

must have been way overexposed, which

means failures in [regulatory] compliance.

The black lung data coming in from

NIOSHs screening programs indicated that

the rise in CWP was most severe in Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia, 26 and

that miners working in small operations

(fewer than 155 miners) were more likely to

be affected than those from larger outfits.27

Compared with miners in other states, these

miners were also younger, had worked in

underground mines for fewer years, and

were more likely to have PMF, the most

severe form of black lung.27 Another study

indicated that abnormal lung function, as

The Coal Workers Health Surveillance Program was created in the early 1970s under the Coal Act. Miners who participate in the voluntary program

receive an X ray upon being hired, then may return for followup X rays every five years. In the mid-2000s, doctors participating in this program

alerted federal authorities to the resurgence of black lung among coal miners in Appalachia. Michael Sullivan/Science Source

A16

volume

124 | number 1 | January 2016 Environmental Health Perspectives

Focus | Black Lung in Appalachia

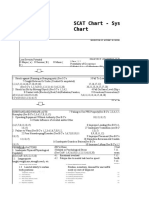

Progressive Massive Fibrosis 5-Year Moving Average

in unsafe situations, he says, but those days

generations.31,32 This dust is more toxic,

measured by spirometry, was three times

were long gone.

more prevalent than CWP, suggesting that

and the miners are inhaling more of it,

The mining companies under which the

CWP was not the only disease affecting

Weissman says. Rather than straight CWP,

violations occurred have been sold or gone

miners lungs.1

he says, what seems to be developing is a

bankrupt, and representatives were unavailmixed dust disease with the worst aspects

The screening program is voluntary, and

able to comment for this story. However,

of both CWP and silicosis. This idea is supbecause less than one-third of miners are estisays Luke Popovich, a spokesman for the

ported, he says, by a recent histopathologic

mated to participate.28 NIOSH researchers

National Mining Association, No one in

analysis of lung samples obtained from coal

conducted further analyses to test the robustthis industry wants a mining accident and

miners with advanced cases of CWP.32

ness of their initial results. The results of

consequently do not tell their employees to

these analyses, reported in 2014, indicated

As for why the increase in CWP is

ignore safety standards for any reason.

that the original estimates of CWP prevamost striking in central Appalachia, the

Jason Hayes, associate director for the

lence among coal miners likely did not overcontent of the coal itself might play a role,

American Coal Council, adds, I cant comstate and may in fact have understated the

says Andrea Harrington, a postdoctoral

ment on any anonymous reports. However,

true prevalence of black lung.29

research scientist at New York University

I will note that there are very clear federal

School of Medicine. The coal mined in

PMF had become nearly nonexistent

and state regulations governing respirable

this region has an unusually high concenin 2000, affecting only 0.08% of CWHSP

dust levels in mines and the safety meatration of pyrite, an iron compound comparticipants and 0.33% of miners who had

sures that are required to reduce employee

monly known as fools gold.33 The iron in

worked at least 25 years belowground.7 But

exposure to dust. All American mines are

as investigators from NIOSH and the Cenpyrite is fairly chemically reactive, stripping

required to follow those regulations.

ters for Disease Control and Prevention

electrons from water molecules and creatmapped the prevalence of PMF moving foring reactive oxygen species in the form of

ward, they found a steep U-shaped curve.

hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, superA New Era in Safety?

By 2012, they reported, the prevalence had

oxide, and/or singlet oxygen.34

Many of the largest coal seams were long

jumped 900% compared with 2000, affectago depleted, leaving only smaller, narrower

A 2005 study reported an association

ing 3.23% of miners with 25-plus years of

seams for modern-day miners. There is still

between the pyrite content of the coal in

work.7 These were levels we hadnt seen

plenty of coal there, says Lilly, but to make

various mining regions and the rates of

room for the large machinery needed to

CWP documented there. 35 Harringtons

since the early 1970s, shortly after modern

extract it requires blasting through not just

dust control measures came into effect,

work shows that pyrite in coal dust increases

coal but also the surrounding rock. A major

says coauthor David Blackley, an epidemiinflammation,36 which increases lung damcomponent of that rock is silica, the major

ologist at NIOSH.

age. 37 Its a dose issue, she says. Your

contributor to silicosis.30,31

For the NIOSH scientists, perhaps the

body can only handle so many particles

most frustrating part of seeing these numbefore it gets overwhelmed.

Weissman and others believe the combers was knowing it didnt have to be this

The inhalation of any dust is likely to

bination of silica and coal dusts is espeway. Coal workers pneumoconiosis is an

cause issues, Harrington adds. However,

cially toxic and is helping drive the surge

entirely preventable disease. They wouldnt

adding a reactive metal to inhaled dust only

in new CWP cases and causing them to

have gotten sick without inhaling way

exacerbates the problems.

progress so much faster than in previous

too much coal dust, says NIOSH

Decreasing numbers of U.S.

coauthor A. Scott Laney.

coal minesa result of competi3.5

To the miners of the Fayette

tion from natural gas and declining

County Black Lung Association,

profits38 means that U.S. coal prothe resurgence was no mystery.

duction

also is going down, in 2013

3.0

According to Terry Lilly, a tall,

falling below 1 billion short tons for

broad-shouldered miner with a gray

the first time in 20 years.39 Pressure

2.5

mustache, weakening of the coal

to increase productivity with fewer

miners union in the 1980s underminers means increased mechani2.0

mined the protections put in place by

zation, which results in smaller and

the Coal Act, leaving workers vulnerthus more harmful dust particles

able. Lilly, who worked as a foreman,

than hand labor can produce. Coal

1.5

says coal mine officials instructed

miners have also been working longer

him to alter measurements of dust

hoursthis means they not only are

1.0

levels in the mines.

exposed for longer periods but also

We k new when the mine

have less time between shifts to clear

inspectors were coming before they

the dust from their lungs.29

0.5

even set foot belowground. Theyd

The miners believe that, whatever

call us and let us know we had a

the cause for the increase, stronger

0.0

visitor, and wed get to work. Wed

labor laws and dust protections will

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

place dust monitors below vents,

help keep their fellow miners from

Year

where theyd constantly get fresh air.

getting sick. Their desire came to

Wed throw up curtains, Lilly says.

pass in 2014, when the Mine Safety

In 1974, shortly after the Coal Act went into effect, PMF

And when the dust got too thick,

and Health Administration issued

affected nearly 3.5% of coal miners with 25 or more years

his choice was to continue working

updated rules for dust exposure.

of underground mining tenure. Rates dropped precipitously

under the new protective rules but have since rebounded,

or lose his job. Several decades ago,

Among provisions set to go into

shooting up 900% over the past 15 years.

when the unions were stronger, hed

effect in 2016, the allowable overSource: Blackley et al. (2014)

felt empowered to halt operations

all dust level was tightened from

7

Environmental Health Perspectives volume 124 | number 1 | January 2016

A17

Focus | Black Lung in Appalachia

2.0 mg/m3 to 1.5 mg/m3, and mine

operators are now required to continuously monitor dust levels and take

immediate action if dust levels are

high.40

The changes also call for CWP

surveillance to be conducted not

only by X ray, but also by lung function testing using spirometry. Robert

Cohen, a professor of pulmonary

medicine at Northwestern University,

says this can catch damage to the

airways as well as scars on the lung

caused by coal mine dust exposure.

Popovich says the mining industry believes more can and must be

done to protect miners from exposure. The industry offered concrete

suggestions to the Mine Safety and

Health Administration during the

agencys rule-making proceeding on

a new dust standard, he says, specifically calling for mandatory participation of all coal miners in the

NIOSH surveillance program and

adoption of a hierarchy of progressively more protective controls to

reduce miners exposure to respirable

dust. 41 Popovich says these suggestions were not adopted by the agency.

Its too soon to say whether the

measures that were adopted will

actually cause CWP numbers to

drop, but researchers hope they will.

A disease that disables around ten

percent of workers would be unacceptable in any other environment,

Blackley says. They shouldnt have

to be exposed to this risk.

20. Gregory JC. Case of particular black infiltration of

the whole lungs resembling melanosis. Edinburgh

Med Surg 36:389394 (1831).

21. Collins EL, Gilchrist JC. Effects of dust upon coal

trimmers. J lnd Hyg 10:101110 (1928).

22. Gough J. Pneumoconiosis of coal trimmers. J Pathol

Bacteriol 51:227285 (1940).

23. Barth PS. The development of the Black Lung Act. In:

The Tragedy of Black Lung: Federal Compensation

for Occupational Disease. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E.

Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

(1987); Available: http://research.upjohn.org/

up_bookchapters/116 [accessed 8 December 2015].

24. Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969.

Public Law No. 91-173. Available: http://www.msha.

gov/SOLICITOR/COALACT/69act.htm [accessed

8 December 2015].

25. Vallyathan V, et al. The influence of dust standards

on the prevalence and severity of coal workers

pneumoconiosis at autopsy in the United States of

America. Arch Pathol Lab Med 135(12):15501556

(2011), doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0393-OA.

26. Suarthana E, et al. Coal workers pneumoconiosis

in the United States: regional differences 40

years after implementation of the 1969 Federal

Coal Mine Health and Safety Act. Occup Environ

Med 68(12):908913 (2011), doi:10.1136/

oem.2010.063594.

27. Laney AS, et al. Potential determinants of coal

workers pneumoconiosis, advanced pneumoconiosis,

and progressive massive fibrosis among underground

coal miners in the United States, 20052009. Am

J Public Health 102(suppl 2):S279S283 (2012),

doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300427.

28. CDC. Work-Related Lung Disease Surveillance

System (eWoRLD). Coal Workers Pneumoconiosis.

CWXSP: Estimated Number of Actively Employed

Workers at Underground Mines and Number of

Miners Examined, 19702006 [website]. Atlanta,

GA:U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Available: http://wwwn.cdc.gov/eworld/Data/

CWXSP_Estimated_number_of_actively_employed_

workers_at_underground_mines_and_number_

of_miners_examined_1970-2006/347 [accessed 8

December 2015].

29. Laney AS, Attfield MD. Examination of potential

sources of bias in the US Coal Workers Health

Surveillance Program. Am J Public Health 104(1):165

170 (2014), doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301051.

30. Leung CC, et al. Silicosis. Lancet 379(9830):2008

2018 (2012), doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60235-9.

31. Laney AS, et al. Pneumoconiosis among

underground bituminous coal miners in the United

States: is silicosis becoming more frequent? Occup

Updated rules for dust exposure call for lung function tests

Environ Med 67(10):652656 (2009), doi:10.1136/

using spirometry, which may help identify other work-related

oem.2009.047126.

lung diseases besides black lung. NIOSH

32. Cohen RA, et al. Lung pathology in U.S. coal

workers with rapidly progressive pneumoconiosis

implicates silica and silicates. Am J Respir Crit Care

Med, doi:10.1164/rccm.201505-1014OC [online

8. MSHA. History of Mine Safety and Health Legislation [website].

29 October 2015].

Arlington, VA:Mine Safety and Health Administration, U.S.

33. Diehl SF, et al. Distribution of arsenic, selenium, and other

Department of Labor (2015). Available: http://www.msha.gov/

trace elements in high pyrite Appalachian coals: evidence for

MSHAINFO/MSHAINF2.HTM [accessed 8 December 2015].

multiple episodes of pyrite formation. Int J Coal Geol 94:238

9. Dodson J, et al. Use of coal in the Bronze Age

249 (2012), doi:10.1016/j.coal.2012.01.015.

Carrie Arnold is a freelance science writer living in Virginia.

in China. The Holocene 24(5):525530 (2014),

34. Harrington

AD, et al. Pyrite-driven reactive oxygen species

Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Discover, New

doi:10.1177/0959683614523155.

formation in simulated lung fluid: implications for coal

Scientist, Smithsonian, and more.

10. Makellar A. An Investigation into the Nature of Black Phthisis;

workers pneumoconiosis. Environ Geochem Health 34(4):527

Or Ulceration Induced by Carbonaceous Accumulation

538 (2012), doi:10.1007/s10653-011-9438-7.

in the Lungs of Coal Miners. Edinburgh:Andrew Jack

REFERENCES

35. Huang X, et al. Mapping and prediction of coal workers

(1846); eBook, Project Gutenberg. Available: http://www.

1. Wang ML, et al. Lung-function impairment among US

pneumoconiosis with bioavailable iron content in the

gutenberg.org/files/21907/21907-h/21907-h.htm [accessed

underground coal miners, 2005 to 2009: geographic

bituminous coals. Environ Health Perspect 113(8):964968

8 December 2015].

patterns and association with coal workers pneumoconiosis.

(2005), doi:10.1289/ehp.7679.

11. McCunney RJ, et al. What component of coal causes coal

J Occup Environ Med 55(7):846850 (2013), doi:10.1097/

36. Harrington AD, et al. Inflammatory stress response in

workers pneumoconiosis? J Occup Environ Med 51(4):462

JOM.0b013e31828dc985.

A549 cells as a result of exposure to coal: evidence

471 (2009), doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a01ada.

2. CDC. Cigarette Smoking Among U.S. Adults Aged 18

for the role of pyrite in coal workers pneumoconiosis

12. Heyder J. Deposition of inhaled particles in the human

Years and Older [website]. Atlanta, GA:U.S. Centers for

pathogenesis. Chemosphere 93(6):12161221, doi:10.1016/j.

respiratory tract and consequences for regional targeting in

Disease Control and Prevention (updated 23 October

chemosphere.2013.06.082.

respiratory drug delivery. Proc Am Thorac Soc 1(4):315320

2015). Available:http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/

37. Harrington AD, et al. Metal-sulfide mineral ores, Fenton

(2004), doi:10.1513/pats.200409-046TA.

tips/resources/data/cigarette-smoking-in-united-states.

chemistry and diseaseparticle induced inflammatory stress

13. Donaldson K, Seaton A. A short history of the toxicology

html[accessed 8 December 2015].

response in lung cells. Int J Hyg Environ Health 218(1):1927

of inhaled particles. Part Fibre Toxicol 9:13 (2012),

3. Antao VC, et al. Rapidly progressive coal workers

(2015), doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.07.002.

doi:10.1186/1743-8977-9-13.

pneumoconiosis in the United States: geographic clustering

38. EIA. Coal Mine Starts Continue to Decline (website).

14. Laney AS, Weissman DN. Respiratory diseases caused by coal

and other factors. Occup Environ Med 62(10) 670674 (2005),

Washington, DC:U.S. Energy Information Administration,

mine dust. J Occup Environ Med 56(suppl 10):S18S22 (2014),

doi:10.1136/oem.2004.019679.

U.S. Department of Energy (updated 23 September 2015).

doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000260.

4. Antao VC, et al. Advanced cases of coal workers

Available:https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.

15. Blackley DJ, et al. Profusion of opacities in simple coal workers

pneumoconiosistwo counties, Virginia, 2006. MMWR Morb

cfm?id=23052[accessed 8 December 2015].

pneumoconiosis is associated with reduced lung function.

Mortal Wkly Rep 55(33):909913 (2006); http://www.cdc.gov/

39. EIA. Annual Coal Report 2013. Washington, DC:U.S. Energy

Chest 148(5):12931299 (2015), doi:10.1378/chest.15-0118.

mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5533a1.htm.

Information Administration, U.S. Department of Energy (April

16. Wang X, et al. Respiratory symptoms and pulmonary

5. Attfield MD, Petsonk EL. Advanced pneumoconiosis among

2015). Available: http://www.eia.gov/coal/annual/pdf/acr.pdf

function in coal miners: looking into the effects of simple

working underground coal minerseastern Kentucky and

[accessed 8 December 2015].

pneumoconiosis. Am J Ind Med 35(2):124131 (1999); PMID:

southwestern Virginia, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

40. Mine Safety and Health Administration. Lowering miners

9894535.

56(26):652655 (2007); http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/

exposure to respirable coal mine dust, including continuous

mmwrhtml/mm5626a2.htm.

17. Kuempel ED, et al. Contributions of dust exposure and

personal dust monitors; Final Rule. Fed Reg 79(84):24813

cigarette smoking to emphysema severity in coal miners in

6. Wade WA, et al. Severe occupational pneumoconiosis among

24994 (2014); http://webapps.dol.gov/federalregister/

the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180(3):257264

West Virginian coal miners: one hundred thirty-eight cases

HtmlDisplay.aspx?DocId=27535&AgencyId=16.

(2009), doi:10.1164/rccm.200806-840OC.

of progressive massive fibrosis compensated between 2000

41. Watzman B. Re: RIN 1219-AB64; Comments on MSHA

and 2009. Chest 139(6):14581462 (2011), doi:10.1378/

18. Petsonk EL, et al. Coal mine dust lung disease. New lessons

Proposed Rule for Lowering Miners Exposure to Respirable

chest.10-1326.

from an old exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187(11):1178

Coal Mine Dust, Including Continuous Personal Dust Monitors

1185, doi:10.1164/rccm.201301-0042CI.

7. Blackley DJ, et al. Resurgence of a debilitating and entirely

[letter]. Arlington, VA:Mine Safety and Health Administration,

preventable respiratory disease among working coal

U.S. Department of Labor (20 June 2011). Available:http://

19. Castranova V, Vallyathan V. Silicosis and coal workers

miners. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190(6):708709 (2014),

www.msha.gov/REGS/Comments/2010-25249/AB64pneumoconiosis. Environ Health Perspect 108(suppl 4):675

doi:10.1164/rccm.201407-1286LE.

COMM-74.pdf[accessed 8 December 2015].

684 (2000); PMID: 10931786.

A18

volume

124 | number 1 | January 2016 Environmental Health Perspectives

You might also like

- Letter To Kentucky AG From MCCCDocument4 pagesLetter To Kentucky AG From MCCCAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- A. Scott Laney, Et Al., Radiographic Disease Progression in Contemporary US Coal Miners With Progressive Massive Fibrosis, 74 Occuptional & Environmental Medicine 517 (2017)Document4 pagesA. Scott Laney, Et Al., Radiographic Disease Progression in Contemporary US Coal Miners With Progressive Massive Fibrosis, 74 Occuptional & Environmental Medicine 517 (2017)AppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- Blackley Et Al - Continued Increase in Lung Transplantation For Coal Workers' Pneumoconiosis in The United StatesDocument4 pagesBlackley Et Al - Continued Increase in Lung Transplantation For Coal Workers' Pneumoconiosis in The United StatesAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- Hicks - Order Granting SJ 10-12-16Document33 pagesHicks - Order Granting SJ 10-12-16AppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- Thapar Decision Denying Reconsideration in HicksDocument14 pagesThapar Decision Denying Reconsideration in HicksAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- Progressive Massive Fibrosis in Coal Miners From 3 Clinics in VirginiaDocument2 pagesProgressive Massive Fibrosis in Coal Miners From 3 Clinics in VirginiaAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- Corrective Action Plan For Martin County Water DistrictDocument4 pagesCorrective Action Plan For Martin County Water DistrictAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- Emails Volume IDocument1,071 pagesEmails Volume IAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM WasteDocument2 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM WasteAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Trip To Salyers Trucking in West LibertyDocument1 pageRE Trip To Salyers Trucking in West LibertyAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- 2016-10-03 Agreed OrderDocument17 pages2016-10-03 Agreed OrderAppCitizensLaw100% (1)

- RE Transportation of TENORM WasteDocument2 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM WasteAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Trip To Fairmont WVDocument1 pageRE Trip To Fairmont WVAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- Emails Volume IIDocument1,167 pagesEmails Volume IIAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM WasteDocument2 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM WasteAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM WasteDocument3 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM WasteAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Estill CountyDocument2 pagesRE Estill CountyAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- FW Attorney General Beshear Announces Investigation of Radioactive Waste in Boyd Estill CountiesDocument1 pageFW Attorney General Beshear Announces Investigation of Radioactive Waste in Boyd Estill CountiesAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM WasteDocument3 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM WasteAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM WasteDocument2 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM WasteAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- FW Attorney General Beshear Announces Investigation of Radioactive Waste in Boyd Estill CountiesDocument2 pagesFW Attorney General Beshear Announces Investigation of Radioactive Waste in Boyd Estill CountiesAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) DOT LTR Re TENORM Ship - From KY - Apr2016Document3 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) DOT LTR Re TENORM Ship - From KY - Apr2016AppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM WasteDocument3 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM WasteAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) - TENORM-DOT-Ship - PA-DeP-FS - Dec2014Document2 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) - TENORM-DOT-Ship - PA-DeP-FS - Dec2014AppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM WasteDocument4 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM WasteAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM WasteDocument3 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM WasteAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- TENORM Piece From Today's Pittsburgh PaperDocument1 pageTENORM Piece From Today's Pittsburgh PaperAppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) - TENORM-DOT-Ship - PA-DeP-FS - Dec2014Document2 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) - TENORM-DOT-Ship - PA-DeP-FS - Dec2014AppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) LLRW Ilegal Dumped in KY - Herald Leader - 2!25!2016Document2 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) LLRW Ilegal Dumped in KY - Herald Leader - 2!25!2016AppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- RE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) Scrap With Rad Material Ship From Beaver Falls - WPXI - 2!25!2016Document2 pagesRE Transportation of TENORM Waste (399) Scrap With Rad Material Ship From Beaver Falls - WPXI - 2!25!2016AppCitizensLawNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Density of Aggregates: ObjectivesDocument4 pagesDensity of Aggregates: ObjectivesKit Gerald EliasNo ratings yet

- Chin Cup Therapy An Effective Tool For The Correction of Class III Malocclusion in Mixed and Late Deciduous DentitionsDocument6 pagesChin Cup Therapy An Effective Tool For The Correction of Class III Malocclusion in Mixed and Late Deciduous Dentitionschic organizerNo ratings yet

- SCAT Chart - Systematic Cause Analysis Technique - SCAT ChartDocument6 pagesSCAT Chart - Systematic Cause Analysis Technique - SCAT ChartSalman Alfarisi100% (1)

- Treating Thyroid Emergencies: Myxedema Coma and Thyroid StormDocument17 pagesTreating Thyroid Emergencies: Myxedema Coma and Thyroid StormMarlon UlloaNo ratings yet

- ADA Design Guide 2010Document7 pagesADA Design Guide 2010Jack BarkerNo ratings yet

- Stepan Formulation 943Document2 pagesStepan Formulation 943Mohamed AdelNo ratings yet

- Generate Profits from Bottled Water Using Atmospheric Water GeneratorsDocument20 pagesGenerate Profits from Bottled Water Using Atmospheric Water GeneratorsJose AndradeNo ratings yet

- Seguridad Boltec Cable PDFDocument36 pagesSeguridad Boltec Cable PDFCesar QuintanillaNo ratings yet

- Carbon Cycle Game Worksheet - EportfolioDocument2 pagesCarbon Cycle Game Worksheet - Eportfolioapi-264746220No ratings yet

- D Formation Damage StimCADE FDADocument30 pagesD Formation Damage StimCADE FDAEmmanuel EkwohNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 Biochem 232 CellsDocument13 pagesLecture 1 Biochem 232 CellsaelmowafyNo ratings yet

- Biosafety FH Guidance Guide Good Manufacturing Practice enDocument40 pagesBiosafety FH Guidance Guide Good Manufacturing Practice enMaritsa PerHerNo ratings yet

- Kidde Ads Fm200 Design Maintenance Manual Sept 2004Document142 pagesKidde Ads Fm200 Design Maintenance Manual Sept 2004José AravenaNo ratings yet

- SK Accessories - ENYAQ - Unpriced - JAN 2023 ART V2Document30 pagesSK Accessories - ENYAQ - Unpriced - JAN 2023 ART V2Viktor RégerNo ratings yet

- Energy-Exergy Performance Evaluation of New HFO Refrigerants in The Modified Vapour Compression Refrigeration SystemsDocument9 pagesEnergy-Exergy Performance Evaluation of New HFO Refrigerants in The Modified Vapour Compression Refrigeration SystemsIjrei JournalNo ratings yet

- Terminal Tractors and Trailers 6.1Document7 pagesTerminal Tractors and Trailers 6.1lephuongdongNo ratings yet

- El Bill PDFDocument2 pagesEl Bill PDFvinodNo ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument6 pagesConcept Paperapple amanteNo ratings yet

- Jaimin PatelDocument3 pagesJaimin PatelSanjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Fluvial Erosion Processes ExplainedDocument20 pagesFluvial Erosion Processes ExplainedPARAN, DIOSCURANo ratings yet

- CV Dang Hoang Du - 2021Document7 pagesCV Dang Hoang Du - 2021Tran Khanh VuNo ratings yet

- Genset Ops Manual 69ug15 PDFDocument51 pagesGenset Ops Manual 69ug15 PDFAnonymous NYymdHgy100% (1)

- Electrical Interview Questions & Answers - Hydro Power PlantDocument2 pagesElectrical Interview Questions & Answers - Hydro Power PlantLaxman Naidu NNo ratings yet

- The Congressional Committee and Philippine Policymaking: The Case of The Anti-Rape Law - Myrna LavidesDocument29 pagesThe Congressional Committee and Philippine Policymaking: The Case of The Anti-Rape Law - Myrna LavidesmarielkuaNo ratings yet

- EMI InstructionsDocument2 pagesEMI InstructionsAKSHAY ANANDNo ratings yet

- Guide To Admissions 2024-25Document159 pagesGuide To Admissions 2024-25imayushx.inNo ratings yet

- Radioimmunoassay MarketDocument5 pagesRadioimmunoassay MarketRajni GuptaNo ratings yet

- Balloons FullDocument19 pagesBalloons FullHoan Doan NgocNo ratings yet

- Impact of Dairy Subsidies in NepalDocument123 pagesImpact of Dairy Subsidies in NepalGaurav PradhanNo ratings yet

- Piaggio MP3 300 Ibrido LT MY 2010 (En)Document412 pagesPiaggio MP3 300 Ibrido LT MY 2010 (En)Manualles100% (3)