Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Part 7-The Architecture of The Twentieth Century - 8-South and South-East Asia

Uploaded by

api-37021770 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

53 views19 pagesOriginal Title

Part 7-The Architecture of the Twentieth Century - 8-South and South-East Asia

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

53 views19 pagesPart 7-The Architecture of The Twentieth Century - 8-South and South-East Asia

Uploaded by

api-3702177Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 19

The Architecture of the Twentieth Century

Chapter 46

SOUTH AND SOUTH-EAST ASIA

Architectural Character

The principal buildings of New Delhi, by Lutyens,

Baker and others, have been dealt with in Chapter 37

under the general heading of colonial architecture.

They are twentieth-century buildings, though for

classification purposes more appropriately placed in

the earlier position in the book as comprising the

architectural apogee of the colonial period in India.

In the event, the period was to last for less than two

decadesafter the completion of Lutyens’s work, until

1945, the end gf.World War II and the formal

achievement of dependence and the partition in

1947, In some pists of south-east Asia, however,

French and Dutcigas well as British dominion was to

last well into the 1960s. Only Hong Kong, occupied

asa Treaty Port sfice 1841, still remains under British

jurisdiction, an arrangement which is due to termin-

ate in 1997,

In India and elsewhere, the imposition of wholly

European models had given way since the tur of the

century to amore sympathetic attitude to local build-

ing forms, especially those of the Moghul Empire—

originally because it was thought that they offered

solutions to the problems of providing comfort in the

hot arid or humid climates prevailing in the region.

Later there began to dawn an understanding of the

nced to respond to the social and cultural as well as

the aesthetic values of Indian civilisation, The forms

of Islamic architecture, however, were often applied

to purely neo-Classical spatial arrangements. Several

buildings in this category are described or mentioned

in Chapter 37, for example public buildings in Mad-

ras by Robert Chisholm and Henry Irwin and in

Hyderabad by Vincent Esch. Islamic forms were

used by British architects also in palaces for the

Maharajas—thet in Mysore by Irwin being anotable

and exuberant example. The resulting buildings were

referred to at the time as Indo-Seracenic, a term also

used in many earlier editions of this book. Through-

out this edition, however, the word Islamic has been

used in the nomenclature for buildings in countries

where the Muslim religion prevails or where Muslim

dynasties influenced events. New Delhi itself is per-

haps the most distinguished example of integration of

1482

Islamic symbolism with Classical forms and even

holds subtle echoes of Hindu motifs—the product is

original and dominating architecture, enshrined in

buildings of high quality.

In India, the status of engineers was modified to

the extent that Consulting Architects were appointed

to the central government. Although by the turn of

the century Victorian eclectic attitudes to design

were beginning to give way to the self-assurance of

so-called Edwardian Baroque, efforts continued to

be made to incorporate Indian forms into the design

of agrowing diversity of building types. This was true

of both private and public architects whose work,

though to some extent overshadowed by Lutyens and

Baker, nevertheless produced notable buildings in

the years up to the beginning of World War If, and in

some cases also after it had ended. Amongst this

number were the first Consultants to the Govern-

ment of India, James Ransome (1865-1944), who

served from 1902 to 1908, and John Begg (1866~

1937), who succeeded him and served until 1921. The

former designed buildings in a number of styles, in-

cluding several in a popular picturesque manner.

Begg spent a few years in South Africa before going

to India, where he worked first in Bombay. He too

was capable of producing buildings in several styles

and wasone of those who soughta means f incorpor-

ating the forms of Moghul architecture into the public

buildings for which he was responsible. He was con-

sultant io the railway and worked for the Post Office

‘as well as designing many fine buildings, including a

hospital and medical school in Delhi and several

colleges. Both architects worked in Burma as well as

India. The tradition of distinguished public service in

architecture was continued into the 1930s by another

Chief Architect to the India Government, Robert

Tor Russell, the designer of Connaught Place (q.v.)

and other buildings in New Delhi.

The influence of Lutyens and Baker persisted in

the work of government and private architects but

was much reduced after World War I, although 2

few British architects worked on in India, Sri Lanka

and other south-east Asian countries after indepen-

dence. But in common with most countries newly

independent of colonial control, the first few decades

SOUTH AND SOUTH-EAST ASIA.

have been marked by a continuation of the Interna-

tional Style introduced by European architects in the

1930s and continued through the 1950s, ’60s and "70s,

both by local architects trained in Europe, Australia

or America and by expatriate architectural practices

commissioned by governments or institutions, It

would be difficult to find a public building or a major

housing project of the period which does not reflect

contemporary European architectural ideals.

‘There are a number of factors which explain the

acceptance of the International Style on such a scale

by Third World countries in the period of up to forty

years since independence. They include the percep-

tion of modern buildings as symbols of progress, the

mode of financing major developments through in-

ternational agencies, and perhaps also the fact that

the decision-makers are often those who have spent

long periods in Western countries in education and

training programmes; indeed a Westernised envi

ment had been superimposed already to 2 major

extent upon their homelands in the colonial period,

especially in urban areas. Itis surprising, neverthe-

less, that those responsible for selecting the creators

of gheir greatest national symbols, the new capitals,

turned to Europe and America—not that anyone

would apply the International Style label to the work

of Le Corbusier or Louis Kahn. though it may well be

applicable to some of the buildings designed by

ernational practices to fill the grids of Doxiadis's

Dynapolis, the combined linear towns of Rawalpindi

and Islamabad.

In the years of planning and (so far) partial imple-

mentation of the new cities, the availability of local

qualified architects has improved. The number of

architectural schools in the region has increased, as

have the numbers receiving architectural education

abroad, resulting in a growing body of architects

designing buildings in their own countries. In many

cases, of course, even education patterns have been

geared to the production of buildings in the Interna-

tional Style, and the impact is of necessity gradual

rather than spectacular, but many changes are al-

ready apparent and others are imminent. The leaders

of such movements, such as Charles Correa in India,

are motivated by the desire to provide environments

suited to indigenous cultures and modes of living as

well as to climate and locality. They base their work

upon the needs of enormous and sill-growing

deprived populations and upon the economic reali-

ties of development finance in the Third World.

Meanwhile, high-rise Bombay (p.1484A) and the

thriving commercialised city-states of the region,

dependent Singapore (p.1484B) and still-colonial

Hong Kong, taking advantage of locational, sirategic

or economic factors, have experienced unpre-

cedented urban development, rivalling even Euro-

pean and American urban centres in their rate of

physical growth,

1483

Examples

Although New Delhi has been largely dealt with in

Chapter 37, it would be remiss not to include here

references to the work of two architects associated

with the offices of Baker and Lutyens respectively,

Henry Alexander Nesbitt Medd (1892-1977) and

Arthur Gordon Shoosmith (1888-1974). Medd

worked in both Delhi and Calcutta and is now re-

membered for his Cathedral Church of the Redemp-

tion, New Delhi (1928 onwards), its soaring composi-

tion rising to a dome with cupola on a low circular

drum, the whole clevated on an octagonal storey with

recessed windows above the square crossing tower. It

is reminiscent of Palladio’s Tl Redentore in Venice

(q.v.). Other buildings by Medd indude the Roman

Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart, New Delhi

(1934), and the New Mint, Calcutta, Shoosmith's

Garrison Church of S. Martin, New Delhi (1928-30),

is a massive unrelieved brick fortress-like building

with plain battered walls and undecorated openings,

recalling the great pylons of Edfu (q.v.). Its scale is

vast and in the true Lutyens New Delhi spirit butalso

imbued with the industrial aesthetic and a nascent

modernism.

Several of the south-east Asian countries remained

under British and other colonial administrations for

up to twenty years after the end of World War II.

During this time many buildings were put up in the

anonymous colonial modern practised by European

architectural firms, whether basgd in their own coun-

tries or abroad, or by architects employed by govern-

ment (for example, in the Public Works Departments

of British colonial administrations). Among the bet-

ter examples in Malaysia (Malaya before 1957) was

work of the PWD in such buildings as Kuala Lumpur

Airport (architect P. S. Merer), or of private archi-

tects Booty, Edwards and Partners in their pleasant

verandah houses in Kuala Lumpur (p.1485A). In

Singapore in the 1950s a number of housing schemes

were implemented: among these were four-storey

walk-up apartment blocks, Queenstown (p.1485B),

some of them by P. R. Davison of the Public Works

Department, others by Lincoln Page of the (then)

Singapore Improvement Trust. Those by the former

have fenestration arrangements which recall High-

point, Highgate, London (q.v.), an impression rein-

forced by the flat treatment of the facades which also

respond to climate in their shuttering and louvre

arrangements; those by the latter are more conven-

tional by European standards of the 1950s, James

Cubitt, Leonard Manasseh and Partners carried out

work in south-east Asia as well as Africa: one of the

more acceptable small buildings of this brief period is

their Broadcasting Studios at Kuala Belait, Indonesia

(Brunei) (1958) (p.1485C).

Much of the discussion of urban planning and

architecture in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh inthe

1484 SOUTH AND SOUTH-EAST ASIA

‘A. Modern Bombay. See p.1483

B. Modern Singapore. See p.1483

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- American Urban ArchitectureDocument99 pagesAmerican Urban Architectureapi-3702177100% (1)

- Part 7-The Architecture of The Twentieth Century - 9-OceaniaDocument25 pagesPart 7-The Architecture of The Twentieth Century - 9-Oceaniaapi-3702177No ratings yet

- Within OfficesDocument194 pagesWithin Officesapi-3702177No ratings yet

- Part 7-The Architecture of The Twentieth Century - 7-JapanDocument14 pagesPart 7-The Architecture of The Twentieth Century - 7-Japanapi-3702177No ratings yet

- Small ApartmentDocument171 pagesSmall Apartmentapi-3702177100% (1)

- 02 AcknowledgementsDocument1 page02 Acknowledgementsapi-3702177No ratings yet

- New HotelDocument55 pagesNew Hotelapi-3702177No ratings yet

- Shop in ItalyDocument19 pagesShop in Italyapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 04 Draughting GuidelinesDocument13 pages04 Draughting Guidelinesapi-3702177No ratings yet

- Within Small HomeDocument199 pagesWithin Small Homeapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 01-About This BookDocument2 pages01-About This Bookapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 0-Xem File Nay Truoc-NguoiDocument6 pages0-Xem File Nay Truoc-Nguoiapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 05 Measurement BasisDocument21 pages05 Measurement Basisapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 11-Fire Protection and Means of EscapeDocument13 pages11-Fire Protection and Means of Escapeapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 10-Thermal and Sound InsulationDocument14 pages10-Thermal and Sound Insulationapi-3702177No ratings yet

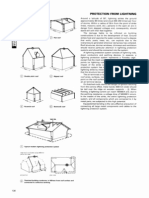

- 12-Lightning Protection and AerialsDocument3 pages12-Lightning Protection and Aerialsapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 24-Workshops and Industrial BuildingsDocument30 pages24-Workshops and Industrial Buildingsapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 07 Construction ManagementDocument8 pages07 Construction Managementapi-3702177No ratings yet

- Refurbishment, Maintenance and Change of UseDocument10 pagesRefurbishment, Maintenance and Change of Useapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 14-Windows and DoorsDocument16 pages14-Windows and Doorsapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 13-Artificial Lighting and DaylightDocument34 pages13-Artificial Lighting and Daylightapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 23 Retail OutletsDocument7 pages23 Retail Outletsapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 25 Agricultural BuildingsDocument17 pages25 Agricultural Buildingsapi-3702177No ratings yet

- Stairs, Escalators and LiftsDocument11 pagesStairs, Escalators and Liftsapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 19-Houses and Residential BuildingsDocument62 pages19-Houses and Residential Buildingsapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 21 Office BuildingsDocument27 pages21 Office Buildingsapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 20-Educational and Research FacilitiesDocument29 pages20-Educational and Research Facilitiesapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 26 Public TransportDocument10 pages26 Public Transportapi-3702177No ratings yet

- 27-Designing For VehiclesDocument14 pages27-Designing For Vehiclesapi-3702177100% (1)