Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adhe Sion : Surface Technology, 14

Uploaded by

kavithavenkatesanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adhe Sion : Surface Technology, 14

Uploaded by

kavithavenkatesanCopyright:

Available Formats

Surface Technology, 14 (1981) 25 - 39

25

ADHE SION *

H. K. PULKER and A. J. PERRY

Balzers AG, FL-9496 Balzers (Liechtenstein)

R. BERGER lnstitut fi~r Experimental-Physik, University of Innsbruck, A-6020 Innsbruck (Austria) (Received February 17, 1981)

Summary A d h e s i o n is defined as the w o r k n e c e s s a r y to s e p a r a t e the c o a t i n g - s u b s t r a t e i n t e r f a c e ; most available m e t h o d s m e a s u r e the load required to strip off the coating. The m a n y q u a n t i t a t i v e and q u a l i t a t i v e m e t h o d s used are presented and the origins of adhesion are discussed. The p a r a m e t e r s influencing the adhesive s t r e n g t h are reviewed: s u b s t r a t e p r e p a r a t i o n , c o a t i n g technique, residual pressure in the v a c u u m c h a m b e r and s u b s t r a t e t e m p e r a t u r e are all found to be significant, and a g i n g effects w h i c h can raise or lower the a d h e s i o n can also be observed. M a n y variables affect the m e a s u r e d a d h e s i o n and m e a n t h a t only a partial analysis is possible in genera] at the present time. This leaves a wide field open for f u r t h e r studies.

1. I n t r o d u c t i o n

and definition

The problems of a d h e s i o n of c o a t i n g s with t h i c k n e s s e s between 0.05 and 50 um are discussed in this paper. In most a p p l i c a t i o n s these c o a t i n g s are not self-supporting but r a t h e r are applied to the surface of a solid body. This solid either can simply f u n c t i o n as a s u b s t r a t e or can have specific properties w h i c h are improved in some w a y by the a p p l i c a t i o n of the coating. I m p r o v e m e n t of the surface is thus defined as an i n t e n t i o n a l and e x a c t a l t e r a t i o n of the optical, electrical, chemical or m e c h a n i c a l properties of the solid surface.

* Invited paper given at a Seminar on Surfaces and Interfaces, Bern, Switzerland, December 3, 1980, which was organized by the Swiss National Science Foundation. 0376-4883/81/0000-0000/$02.50 ~ Elsevier Sequoia/Printed in The Netherlands

26

In all these cases sufficiently good a d h e s i o n b e t w e e n the p a r t n e r s is of' p a r a m o u n t i m p o r t a n c e to the u s e f u l n e s s of such a system. These c o a t i n g s c a n be p r o d u c e d by v a r i o u s t e c h n o l o g i e s such as p h y s i c a l v a p o u r d e p o s i t i o n (PVD) in a v a c u u m or c h e m i c a l v a p o u r d e p o s i t i o n (CVD) from the g a s e o u s phase. The p r e p a r a t i o n and the p r o d u c t i o n t e c h n o l o g y c a n g r e a t l y influence the w a y i n ' w h i c h the m a t e r i a l s adhere. W h a t t h e n e x a c t l y is adhesion'? N e w e r physics, c h e m i s t r y and t e c h n i c a l d i c t i o n a r i e s define a d h e s i o n as " . . . the b o n d or the s t r e n g t h of the bond b e t w e e n two m a t e r i a l s or two bodies; also the bond of i n d i v i d u a l m o l e c u l e s to the i n t e r f a c e s u r f a c e s " [1 -:3]. The A S T M defines a d h e s i o n as the " C o n d i t i o n in which two s u r f a c e s are held t o g e t h e r by e i t h e r v a l e n c e forces or by m e c h a n i c a l a n c h o r i n g or by b o t h t o g e t h e r . " [4]. T h e s e b o n d i n g forces could be v a n der W a a l s ' forces, elect r o s t a t i c forces a n d / o r c h e m i c a l b o n d i n g forces which are effective across the interface. In this p a p e r the word a d h e s i o n will be used as a s y n o n y m for " t h e a d h e r e n c e " of a film to its s u b s t r a t e and, in its b r o a d e r sense, for the " a d h e s i v e s t r e n g t h " . A d h e s i o n is defined by the w o r k n e c e s s a r y to s e p a r a t e a t o m s or m o l e c u l e s at the interface. A d i s t i n c t i o n c a n be m a d e b e t w e e n the m a x i m u m possible a d h e s i o n (basic a d h e s i o n ) of a s y s t e m w h i c h r e p r e s e n t s the m a x i m u m a t t a i n a b l e v a l u e on the one h a n d a n d the e x p e r i m e n t a l l y m e a s u r e d a d h e s i o n [5, 6] on the other. T h e m a c r o s c o p i c e x p e r i m e n t a l l y m e a s u r e d a d h e s i o n v a l u e s are det e r m i n e d by the basic adhesion, the m e c h a n i c a l p r o p e r t i e s of the fihn and the f r a c t u r e m e c h a n i s m in the s e p a r a t i o n p r o c e s s [7, 8]. The r e l a t i o n b e t w e e n the e x p e r i m e n t a l l y m e a s u r e d a d h e s i o n EA and the basic a d h e s i o n BA is g i v e n by

EA = BA -

IS M S M

( 1)

w h e r e IS is the i n t e r n a l m e c h a n i c a l stress a n d M S M is the method-specific e r r o r of m e a s u r e m e n t . The basic a d h e s i o n c a n n o t u s u a l l y be d e t e r m i n e d b e c a u s e the size of the m e a s u r e m e n t e r r o r c a n seldom be estimated. T h e e x p e r i m e n t a l l y m e a s u r e d a d h e s i o n is given in u n i t s of force or e n e r g y per u n i t s u r f a c e area. A r e l a t i o n b e t w e e n the e n e r g y Waa of a d h e s i o n a n d the force of a d h e s i o n c a n only be d e r i v e d w h e n a r e a s o n a b l e a n d c o n c l u s i v e e s t i m a t e of the p a t h followed by the a d h e s i v e force F(x) o v e r the dividing d i s t a n c e x b e t w e e n the film a n d the s u b s t r a t e s u r f a c e c a n be m a d e [6]: e Wad =~ F(x) dx (2)

.y

The s t r e n g t h of the a d h e s i o n a c r o s s the i n t e r f a c e c a n be d i s t r i b u t e d v e r y u n e v e n l y b e c a u s e the s t r u c t u r e s of the s u b s t r a t e s u r f a c e and of the film are often h e t e r o g e n e o u s . C o n t a m i n a n t s c o v e r i n g v e r y small a r e a s and m o n o m o l e c u l a r c o n t a m i n a n t s on the s u b s t r a t e s u r f a c e c a n also c a u s e local c h a n g e s in the a d h e s i v e s t r e n g t h . T h u s the e x p e r i m e n t a l l y d e t e r m i n e d a d h e s i o n v a l u e s should be r e g a r d e d as a v e r a g e v a l u e s across the i n t e r f a c e surfaces investigated.

27

2. M e t h o d s

of measurement

T h e i n d i v i d u a l m e t h o d s of m e a s u r e m e n t u s e d to d e t e r m i n e t h e d e g r e e of a d h e s i o n c a n be c l a s s i f i e d a n d s u b d i v i d e d a c c o r d i n g to v a r i o u s c r i t e r i a , e.g. m e c h a n i c a l a n d n o n - m e c h a n i c a l m e t h o d s . A n e x a m p l e of a s i m p l e q u a l i t a t i v e t e s t is s h o w n i n Fig. 1.

(a)

(d)

(b)

(e)

(c)

(f)

Fig. 1. Qualitative test to check film adhesion by bending. The scanning electron micrographs (a) - (f) were obtained at various magnifications. The specimen examined is an Ni-Fe substrate coated with a rhenium film 10 ~m thick which had been applied by ion plating. When the specimen is bent to a radius of 0.6 mm [9] the close-packed crystallite columns develop cracks as the substrate is stretched. The micrographs show that the film has not separated from the substrate. Therefore the adhesion is good, I n t h e p r a c t i c a l a p p l i c a t i o n of a m e a s u r i n g m e t h o d it is i m p o r t a n t to k n o w , a m o n g o t h e r t h i n g s , w h e t h e r t h e m e t h o d c a n be c a r r i e d o u t w i t h o u t

28

d e s t r o y i n g t h e t e s t o b j e c t s a n d w h e t h e r it c a n p r o v i d e r e p r o d u c i b l e r e s u l t s a n d t h e size o f t h e m e t h o d - s p e c i f i c e r r o r o f m e a s u r e m e n t . T h e s i m p l i c i t y o f t h e m e a s u r e m e n t a p p a r a t u s a n d t h e t i m e n e c e s s a r y to m a k e t h e m e a s u r e m e n t s h o u l d a l s o be t a k e n i n t o a c c o u n t . A n o t h e r p r a c t i c a l c o n s i d e r a t i o n is t h e u s e o f a m e a s u r e m e n t m e t h o d t h a t s i m u l a t e s as c l o s e l y as p o s s i b l e t h e t y p e of s t r e s s to w h i c h t h e c o a t i n g / s u b s t r a t e s y s t e m w i l l be s u b j e c t e d in s e r v i c e . T a b l e s 1 a n d 2 l i s t a n u m b e r o f m e t h o d s o f m e a s u r i n g t h e a d h e s i o n o f t h i n films w h i c h h a v e a p p e a r e d in t h e literature. TABLE 1 Mechanical methods of determination

Qualitative

Scotch tape test [6, 10 - 14] Abrasion test [12, 15] Bend and stretch test [8, 16] Shearing stress test [16 - 18]

Quantitative

Direct pull-off method [8, 19 -33] Moment or topple test [3,1 37] Electromagnetic tensile test ]38] l~aser spalation test 139] Ultracentrifuge test [6, 16, 10- 4,11 Ultrasonic test ]6. 701 Peeling test [6. 45 - 48] Tangential shear test [49. 501 Scratch test [44, 46, 51 - 67]

TABLE 2 Non-mechanical methods of determination

Qualitative

X-ray diffraction test [65]

Quantitative

Thermal method [68, 69] Capacity test 16, 7l] Nucleation test [46]

2.1. Mechanical methods

I n m e c h a n i c a l m e t h o d s a d h e s i o n is m e a s u r e d b y a p p l y i n g a t b r c e to t h e coating/substrate system under examination. This force causes a mechanical s t r e s s a t t h e i n t e r f a c e w h i c h s h o u l d r e m o v e t h e film f r o m t h e s u b s t r a t e o n c e the stress has been increased to an appropriate level. The definitions given h e r e for " m e c h a n i c a l s t r e s s " a r e t h o s e c o m m o n l y u s e d in t h e field o f p h y s i c s and are thus different from those definitions which have become established in t h i n film l i t e r a t u r e . T h e s t r e s s c a n be e i t h e r t e n s i l e p e r p e n d i c u l a r to t h e i n t e r f a c e o r s h e a r i n g p a r a l l e l to t h e i n t e r f a c e . In p r a c t i c a l a p p l i c a t i o n s a c o m b i n a t i o n o f t h e s e t w o t y p e s of s t r e s s u s u a l l y o c c u r s . T h a t f o r c e o r e n e r g y a t w h i c h t h e s e p a r a t i o n o f film a n d s u b s t r a t e first t a k e s p l a c e is t a k e n as a n i n d e x o f t h e e x p e r i m e n t a l l y m e a s u r e d a d h e s i o n [6].

29

In addition to the stress produced by e x t e r n a l forces, very strong i n t e r n a l stresses i n h e r e n t in the film (intrinsic stress) also affect the i n t e r f a c e and influence the e x p e r i m e n t a l adhesion m e a s u r e m e n t results in an u n d e t e r m i n e d way. In extreme cases very strong i n t e r n a l stresses alone can lead to d e t a c h m e n t of the film [72, 73] or to cohesive failures in the s u b s t r a t e [74]. In general, failure and thus s e p a r a t i o n can a p p e a r in any of five regions (Fig. 2) [75]. Region 1 is the inside of the film and region 5 is the bulk m a t e r i a l of the s u b s t r a t e which is sufficiently distant from th~ interface. If the s e p a r a t i o n occurs in one of these two regions then failure is cohesive. On an atomic scale, region 3 can be e i t h e r a very sharply defined i n t e r f a c e or a very diffuse i n t e r f a c e layer. In o r d e r to be able to m e a s u r e the adhesion, the s e p a r a t i o n must take place in this region [75, 76]. Even with a m a t e r i a l t r a n s i t i o n of the m o n o l a y e r - o n - m o n o l a y e r type, the changes in some physical c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s (e.g. elasticity and electrical i n t e r f a c e p h e n o m e n a ) t a k e place c o n t i n u o u s l y . When there is an i n t e r f a c e layer (e.g. t h r o u g h diffusion) the t r a n s i t i o n a l area increases in size. For this r e a s o n a distinction is made between the m e c h a n i c a l b e h a v i o u r of the interface layers in regions 2 or 3 and t h a t of the inner regions of film 1 or s u b s t r a t e 5 [75, 76].

Schicht 1

--j2 --3

Substrat 5

Fig. 2. The five regions [75] in which separation can take place.

A s e p a r a t i o n exclusively at the interface is assumed to be improbable a c c o r d i n g to the " w e a k b o u n d a r y t h e o r y " [77, 78]. Rather, the s e p a r a t i o n should always o c c u r in the bulk regions of coating or s u b s t r a t e (cohesive failure) or in a finitely thick " w e a k l a y e r " (interface layer) between the two substances. A failure within the weak i n t e r f a c e layer is r e g a r d e d as an adhesive failure. The weak layer can be a brittle oxide l a y e r or an absorbed and occluded l a y e r of gas a n d / o r some o t h e r kind of c o n t a m i n a t i o n . The basis of a n o t h e r t h e o r y [79] is the t r i g g e r i n g of a f r a c t u r e at preexisting cracks in the s u b s t r a t e or within the film a c c o r d i n g to the so-called G r i f f i t h - O r o w a n c r i t e r i o n [19, 80]: a2 = c o n s t a n t x

EG/l

(3)

where E is the modulus of elasticity, G is the work per unit surface area r e q u i r e d for c r a c k propagation, l is the length of the longest c r a c k s in existence and a is the force per unit surface area required for c r a c k propa-

gation. The c r a c k thus !brined grows in a direction normal to t h a t of the applied m e c h a n i c a l stress. The actual fl'acture is assumed to be a t r a n s f o f m a t i o n of e n e r g y either" into dissipative e n e r g y (e.g. heat) stored as elastic d e f o r m a t i o n or supplied externally, It must also be assumed that an energy t r a n s % r takes place from the area a r o u n d the f r a c t u r e to the f r a c t u r e zone. F r a c t u r e can also extend across several of the given regions. If the s e p a r a t i o n of the c o a t i n g from the s u b s t r a t e takes place inside or a r o u n d the interface layer, the force or e n e r g y n e c e s s a r y for the s e p a r a t i o n is a m e a s u r e of the e x p e r i m e n t a l l y m e a s u r e d adhesion [76]. However, if the s e p a r a t i o n takes place deep inside the film or substrate, it is a cohesion fracture, i,c. the adhesion forces are s t r o n g e r t h a n the cohesion forces. From a q u a l i t a t i w , point of view, the adhesion is considered to be bad if a s e p a r a t i o n in the interface l a y e r can be caused. However, if a s e p a r a t i o n occurs in the bulk. the adhesion is good. Q u a n t i t a t i v e values can only be obtained when the force used to lift the c o a t i n g can be measured. Individual m e a s u r e m e n t m e t h o d s are distinguished from one a n o t h e r by the way the load is coupled to the sample system and then by the way in which it is applied. These criteria allow a division into m e t h o d s which can remove the c o a t i n g t h r o u g h (a) a force applied p e r p e n d i c u l a r l y to the interface layer or (b) a tbrce applied at v a r i o u s angles to the interface layer. An upper limit of the t r a n s f e r a b l e force, and thus a m a x i m u m measurable adhesion value, results from the fact that in almost all the m e a s u r i n g m e t h o d s (with the exception of', for example, u l t r a c e n t r i f u g e or heat expansion methods) a t r a c t i o n piece must be a t t a c h e d m e c h a n i c a l l y . Thus this limit is d e p e n d e n t on the load c a p a c i t y or degree of fixation of the methodspecific a t t a c h m e n t (e.g. gluing or soldering). B e c a u s e of the v a r y i n g a t t a c h m e n t t e c h n i q u e s and the individual t r a n s f e r devices (Scotch tape, needles for s c r a t c h i n g etc.) f u r t h e r uncontrolled stresses can be caused in the interface layer in addition to the c o n t r o l l e d m e c h a n i c a l stress p r o d u c e d externally. Such additional stress ('an be caused, for example, by drying, p o l y m e r i z i n g or stiffening of the glue l a y e r or the solder l a y e r used for the t r a c t i o n piece. It can also o c c u r b e c a u s e of p l a s t i c - e l a s t i c d e f o r m a t i o n of the t r a c t i o n piece itself d u r i n g a test. The e x p e r i m e n t a l l y d e t e r m i n e d a d h e s i o n values are thus not free from effects due to the m e a s u r e m e n t m e t h o d used. Therefore it is u n f o r t u n a t e l y n o t a l w a y s possible to c o m p a r e m e a s u r e m e n t s obtained by different methods.

2.2. Non-mechanical methods

With the exception of the n u c l e a t i o n method, n o n - m e c h a n i c a l m e t h o d s to m e a s u r e adhesion are not very well developed, and their field of applic a t i o n is severely limited. These m e t h o d s can, in a n y case, be used for basic i n v e s t i g a t i o n s . Even the n u c l e a t i o n m e t h o d is too complicated for use for t e c h n o l o g i c a l applications b e c a u s e it requires too m u c h e q u i p m e n t and t a k e s too m u c h time. F o r this r e a s o n we shall not discuss it in more detail here.

31

3. C a u s e s o f a d h e s i o n

3.1. Interface layer

The quality of adhesion between solids, e.g. between a film and its substrate, depends to a large extent on the microstructure of the interface layer that is being formed. The following types of interface layers can be distinguished [8, 69, 81].

3.1.1. Mechanical interface layer

This type of interface layer forms on rough porous substrates. The film material fills the pores and o.ther morphologically advantageous places when there is sufficient surface mobility and wetting, and a mechanical anchor is formed. The adhesion depends on the physical characteristics (particularly the shear strength and the plasticity) of the combination of materials.

3.1.2. Monolayer on monolayer

This interface is characterized by an abrupt transition from the film material to the substrate material. The transition region has a thickness 2 5 A. Interfaces of this type form when no diffusion occurs; there is little or no chemical reaction and the substrate surface is dense and smooth.

3.1.3. Chemical bonding interface layer

This type of interface layer is characterized by a constant chemical composition across several lattices. The formation of the interface layer results from the chemical reactions of film atoms with substrate atoms which may also be influenced by the residual gas. A distinction is made between intermetallic bonds and alloys and chemical bonds such as oxides, nitrides etc.

3.1.4. Diffusion interface layer

This interface layer is characterized by a generalized constant change in the lattice and the composition in the film-substrate transition area. At least partial solubility is required for diffusion between the film and the substrate material to take place. The necessary energy (1 - 5 eV) must be supplied from elsewhere, e.g. when copper is evaporated onto an unheated gold substrate the heat of condensation is sufficient for diffusion to take place. Diffusion layers have advantageous characteristics as transitional layers between very different materials, e.g. for reducing mechanical stresses resulting from thermal expansion.

3.1.5. Pseudodiffusion interface layer

This type of layer can be formed by implantation at high particle energies or by sputtering and ion plating of the substrate materials with simultaneous condensation of the film material. Pseudodiffusion interface layers have the same advantageous characteristics as diffusion interface layers, but in contrast with the latter they can be formed from

m a t e r i a l s t h a t do not m u t u a l l y diffuse, ion b o m b a r d m e n t before c o a t i n g can i n c r e a s e the " s o l u b i l i t y " in the i n t e r f a c e layers, t h u s i n c r e a s i n g the diffusion by p r o d u c i n g a h i g h e r c o n c e n t r a t i o n of point defects [82] and stress g r a d i e n t s [83]. One type of i n t e r f a c e l a y e r seldom o c c u r s alone. In n o r m a l practice. c o m b i n a t i o n s of the v a r i o u s types of i n t e r f a c e layers often o c c u r simultaneously.

3.2. Types of bonding

A d h e s i o n forces lying b e t w e e n 0.1 and 10 eV can be classified as follows: p h y s i s o r p t i o n , c h e m i s o r p t i o n and c h e m i c a l bonding. T h e c h a r g i n g effect [37] c a n also be classified as p h y s i s o r p t i o n . When two m a t e r i a l s with v e r y different e l e c t r o n affinities are combined, an e l e c t r i c a l double l a y e r forms which also c o n t r i b u t e s to the adhesion. P h y s i s o r p t i o n c o n t r i b u t e s up to a p p r o x i m a t e l y 0.5 eV to the adhesion. The force lies b e t w e e n 10 ~ and 10 s dyn cm 2 The i n t e r a c t i o n b e t w e e n film and s u b s t r a t e a t o m s which is described as c h e m i s o r p t i o n c a n r e s u l t in s t r o n g bonds w h e n e l e c t r o n s are shifted or e x c h a n g e d . In t r u e c h e m i c a l b o n d i n g s u c h as c o v a l e n t and ionic b o n d i n g as well as in m e t a l b o n d i n g the b o n d i n g forces are very strong, d e p e n d i n g on the degree of e l e c t r o n t r a n s f e r . In c o v a l e n t and ionic b o n d i n g the r e s u l t i n g bonds tend to be brittle, w h e r e a s in m e t a l b o n d i n g ductile alloys are often produced. The e n e r g y c o n t r i b u t e d to the a d h e s i o n from chemical bonds r a n g e s from 0.5 to a b o u t 10 eV. The forces are g r e a t e r t h a n or equal to 10 L1 dyn cm 2 This a p p a r e n t l y c l e a r p i c t u r e of differing i n t e r f a c e l a y e r s and types of i n t e r a c t i o n is c o m p l i c a t e d by the fact t h a t s u r f a c e s do not. b e h a v e u n i f o r m l y b e c a u s e t h e y are u n d e r the influence of the so-called a c t i v e and passive centres. A c t i v e c e n t r e s include g r a i n b o u n d a r i e s , dislocations, v a c a n c i e s or c r y s t a l l i t e faces with v a r y i n g free e n e r g i e s and a c t i v a t i o n energies of' c h e m i s o r p t i o n . P a s s i v e centres, w h i c h are a n a l o g o u s to a c t i v e centres, are s u r f a c e a r e a s w h i c h h a v e a l r e a d y been c o v e r e d with foreign m a t e r i a l so t h a t little or no c h e m i s o r p t i o n c a n t a k e place. It should be n o t e d t h a t the q u a l i t y of a d h e s i o n i m p r o v e s w i t h t i m e in some cases (e.g. silver on glass). This p h e n o m e n o n c a n be e x p l a i n e d in t e r m s of the slow (diffusion) formagion of an o x y g e n - b o n d e d i n t e r f a c e layer. O t h e r i n v e s t i g a t i o n s m a d e u s i n g the s c r a t c h test [82, 84] of the c h a n g e s in adh e s i o n t h a t t a k e place w i t h t i m e for m e t a l films on p o l y m e r s u b s t r a t e s h a v e s h o w n t h a t t h e r e is a m a r k e d i m p r o v e m e n t in the a d h e s i o n of the gold film o v e r a period of time. In this case the m a j o r p a r t of the i m p r o v e m e n t in a d h e s i o n was a t t r i b u t e d to the slow f o r m a t i o n of an e l e c t r o s t a t i c double layer. This was p r o v e d by b o m b a r d i n g t h e film with ions from a glow d i s c h a r g e w h i c h b r o k e d o w n the double layer, w h e r e u p o n the a d h e s i o n r e t u r n e d to its o r i g i n a l l o w e r v a l u e [82]. This series of e x p e r i m e n t s showed t h a t the e l e c t r o s t a t i c c o m p o n e n t s c o n t r i b u t e significantly to adhesion.

33

This observation confirms that adhesion seldom comes about only t h ro u g h reciprocal action but r at her that it is determined by the combined effects of various intermolecular atomic interactions.

4. P a r a m e t e r s influencing adhesion

The adhesion of thin films is influenced by a large number of parameters. Some of these are defined by the choice of materials for the coating and the substrate. The others are influenced by the preparation of the substrate, the coating process and the handling of the film-substrate combination after the coating process is completed. 4.1. Coating and substrate materials In most cases the substrate is given and fixed, and the coating is applied to change certain of its characteristics, e.g. antireflection coating of lenses, corrosion protection of a metal or improvement of hardness. The choice of material combinations in each case is often quite limited because of the application for which the system is intended. The choice of the combination of substances (if the film is to be evaporation coated) determines whether the interface layer will be of the diffusion type or the chemical bond type, or whether weak reciprocal action forces will be effective across the interface. If it is expected that the adhesion between the chosen materials will be weak, then the adhesion can be improved by the addition of an appropriate intermediate layer (compound system). The most common application of intermediate layers is to improve the adhesion of gold films on oxide substrates, e.g. glass. Metals such as chromium which oxidize and alloy easily are usually used as the intermediate layer. The chromium adheres very well to the substrate because of oxidation, and the chromium and gold form a diffusion interface layer which also has very good adhesion [85]. The adhesion of evaporated aluminium films on glass can be greatly improved by using nickel or chromium in a similar way [56]. The evaporation coating of metal alloys with low internal stresses (e.g. 75(~o Ti and 25% Cr) is a special case whereby the components of the alloy themselves often have a very high internal stress [86]. 4.2. Substrate preparation The formation of an interface layer and thus the adhesion are greatly influenced by the physical and chemical structure of the substrate surface and the neighbouring areas as well as by the morphology of the surface (planicity, waviness and roughness). The chemical composition of a surface itself is almost always different from that of the bulk of the material. Prior treatment of the surface, e.g. cutting and polishing, changes not only the mechanical structure but also the chemical structure of the surface. This can have both positive and negative effects on adhesion. For example, a layer comprising the polishing

a g e n t (usually an oxide), r e a c t i o n products, w a t e r and glass particles (Beilby film) forms on the s u b s t r a t e surface w h e n glass is polished [87]. Therefore the s u b s t r a t e should be prepared in such a way as to provide a defined and r e p r o d u c i b l e surface. There are m a n y physical and chemical c l e a n i n g and p r e p a r a t i o n m e t h o d s t h a t are capable of doing this. The desired c l e a n i n g is often a c h i e v e d by using a c l e a n i n g process w h i c h has a c o m b i n a t i o n of individual steps. W h e n w o r k i n g out a c l e a n i n g process it must be remembered w h i c h c o n t a m i n a n t s are to be cleaned from w h i c h surface m a t e r i a l s (metal, ceramic etc.).

4.3. Influence of the coating method

The f o r m a t i o n of the interface l a y e r is very s t r o n g l y influenced by the c o a t i n g process. In the case of films deposited by physical v a p o u r deposition a d i s t i n c t i o n is made b e t w e e n three different m e t h o d s of a p p l y i n g the c o a t i n g ( e v a p o r a t i o n in a h i g h v a c u u m , s p u t t e r i n g and ion plating), and the f o r m a t i o n of an i n t e r f a c e layer and the a d h e s i o n are influenced by the energy of the v a p o u r particles c o n d e n s i n g on the s u b s t r a t e as well as by the residual gas pressure (see Fig. 3).

_.1 ~, L

(a)

{b)

(c)

Fig. 3. Schematic diagram of the principle {}f physical coating processes [18]: {a) evaporation coating in a vacuum: (b) cathode sputtering; {{9 ion plating. P, tromping system; V, evaporator: S, snbstratc: T, target: E, energy supply to e v a p o r a t o r : P1, plasma: G, controlled gas supply; UT, negative target w~ltage (cathode voltage): Us , substrate voltage. The a v e r a g e kinetic e n e r g y of the v a p o u r particles on e v a p o r a t i o n is 0.1 - 0.2 eV. From this low e n e r g y it must be c o n c l u d e d t h a t only lightly adsorbed foreign m a t e r i a l films with a b s o r p t i o n energies of less t h a n 0,1 eV can be removed in this process and that wq)our particles c a n n o t in general be implanted u n d e r the s u b s t r a t e surface. Therefore the nuclei generally form on or in an a b s o r p t i o n layer a d h e r i n g to the s u b s t r a t e w h i c h can f u n c t i o n b o t h as a weak b o u n d a r y layer and as an adhesion layer t h r o u g h chemical bonding. In c a t h o d e s p u t t e r i n g the film m a t e r i a l e n e r g y is r a t h e r h i g h e r (1 - 10 eV) [ 7 ] . In ion plating a c o m b i n a t i o n of e v a p o r a t i o n (because of the high deposition rate) and s p u t t e r i n g (because of the high particle energy) allows particle energies g r e a t e r t h a n 100 eV to be obtained [88], Here c o n d e n s a t i o n on the s u b s t r a t e takes place u n d e r the s i m u l t a n e o u s influence of ions and

35

highly energized n e u t r a l particles (plasma) at pressures between 10 3 and 10-2 mbar. The highly energized particles can r e m o v e most of the a b s o r p t i o n l a y e r w h e n t h e y arrive at the surface. In addition, s p u t t e r i n g of the subs t r a t e surface ( p a r t i c u l a r l y for ion plating) and i m p l a n t a t i o n of particles of the film m a t e r i a l can also occur. Thus a reciprocal action between the film and the s u b s t r a t e m a t e r i a l is possible, e.g. a chemical reaction, or perhaps forced diffusion (pseudodiffusion). These are the reasons why films deposited by s p u t t e r i n g and ion plating generally a d h e r e m u c h b e t t e r t h a n e v a p o r a t e d films. In addition to the kinetic e n e r g y level of the film material, the pressure and composition of the residual gas in the coating e q u i p m e n t also d e t e r m i n e the c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s and adhesion of the film. If the film is produced by e v a p o r a t i o n in a high vacuum, the pressure should be k e p t below 10 5 _ 10 6 mbar. If this is not done the low e n e r g y v a p o u r particles will be dispersed too m u c h in the residual gas at the usual distance between e v a p o r a t o r and s u b s t r a t e (0.5 m). A l t h o u g h 0.5 m corresponds to a m e a n free path ). at a pressure of 10 4 mbar, c a l c u l a t e d from the simplified e q u a t i o n

this means t h a t only 40% of the v a p o u r atoms r e a c h the s u b s t r a t e w i t h o u t collisions with the residual gas particles which result in a r e d u c t i o n of e n e r g y and a c h a n g e of d i r e c t i o n [89]. F u r t h e r m o r e , the n u c l e a t i o n b e h a v i o u r depends on the composition of the residual gas a b s o r p t i o n layers ( p a r t i c u l a r l y condensed w a t e r vapour) on the s u b s t r a t e surface which affects the adhesion. It should be noted that, in addition to the m i c r o s t r u e t u r e and the m o l e c u l a r s t r u c t u r e of the e v a p o r a t e d films, the adhesion is also influenced by the angle at which the v a p o u r particles hit the substrate. No difference in adhesion can be observed for p e r p e n d i c u l a r angles of incidence 0 between 0 and a b o u t 4 8 , but at values of 0 of 60 the film m i c r o s t r u c t u r e becomes porous and the adhesion is g r e a t l y reduced [48]. When the pressure is high (10 2 . 10 1 mbar) during e v a p o r a t i o n coating the p r o p o r t i o n of v a p o u r particles r e a c h i n g the s u b s t r a t e and c o n d e n s i n g t h e r e is so small, because of the s c a t t e r i n g resulting from collisions with residual gas molecules, t h a t the adhesion is bad. In contrast, a sufficient n u m b e r of highly energized v a p o u r particles r e a c h the s u b s t r a t e and condense t h e r e despite multiple collisions when s p u t t e r i n g or ion plating is used. S p u t t e r i n g gold films onto glass s u b s t r a t e s using oxygen as the s p u t t e r i n g gas is a special case. If a r g o n is used as the noble gas atmosphere, t h e n the adhesion of the gold is only m a r g i n a l l y b e t t e r t h a n t h a t of e v a p o r a t e d fihns. If a m i x t u r e of oxygen and a r g o n is used, the adhesion improves in p r o p o r t i o n to the oxygen c o n t e n t of the s p u t t e r i n g gas mixture. When the o x y g e n c o n t e n t of the gas m i x t u r e is only 20'I/o, the film adheres so

36

s t r o n g l y t h a t it can no longer be r e m o v e d from the s u b s t r a t e w i t h o u t d e s t r o y i n g it [51]. H o w e v e r , good a d h e s i o n is o b t a i n e d w h e n gold fihns are ion plated o n t o glass in an a r g o n a t m o s p h e r e [90]. The s u b s t r a t e t e m p e r a t u r e h a s a very s t r o n g effect on adhesion. T h u s the r e - e v a p o r a t i o n rate. the s u r f a c e mobility, the diffusion and the prop e n s i t y of the a t o m s to c h e m i c a l r e a c t i o n s are s t r o n g l y affected by the s u b s t r a t e t e m p e r a t u r e . This i n d i c a t e s t h a t the v a r y i n g a d h e s i o n v a l u e s o b t a i n e d are d e p e n d e n t on the s u b s t r a t e t e m p e r a t u r e , and this can be e x p l a i n e d in t e r m s of r e a c t i o n s b e t w e e n the film and the s u b s t r a t e m a t e r i a l [27], which in t u r n are d e p e n d e n t on the s u b s t r a t e t e m p e r a t u r e .

4.4. Aging

In m a n y cases the f i l m - s u b s t r a t e s y s t e m is not t o t a l l y stable once the c o a t i n g process h a s ended, and it c o n t i n u e s to c h a n g e p h y s i c a l l y and c h e m i c a l l y until it r e a c h e s a stable c o n d i t i o n [88]. The a d h e s i o n of' the film to its s u b s t r a t e often u n d e r g o e s m a r k e d c h a n g e s d u r i n g this time. T h r e e processes, which g e n e r a l l y p r o g r e s s slowly, are r e s p o n s i b l e tbr this aging: c h e m i c a l r e a c t i o n s in the i n t e r f a c e l a y e r a r e a : solid body diffusion across the i n t e r f a c e l a y e r ; c h a n g e s in the c r y s t a l s t r u c t u r e ( r e c r y s t a l l i z a t i o n t h r o u g h self-diffusion). T h e s e processes are s t r o n g l y d e p e n d e n t on t e m p e r a t u r e . T h e i r speed u s u a l l y i n c r e a s e s with i n c r e a s i n g t e m p e r a t u r e [55, 58, 91].

5. F i n a l c o m m e n t s

T h e r e are two i m p o r t a n t a s p e c t s of the a d h e s i o n of thin films. F r o m the a c a d e m i c a s p e c t a d h e s i o n itself' is an i n t e r e s t i n g phenomenon. Of special i n t e r e s t are the n a t u r e and degree of the forces r e a c t i n g across the i n t e r f a c e w h i c h a c t u a l l y effect this a d h e s i o n (basic adhesion). F r o m the p r a g m a t i c a s p e c t the t o t a l a d h e s i v e s t r e n g t h of the e n t i r e film to the s u b s t r a t e in a p r a c t i c a l s y s t e m has to be considered. M e c h a n i c a l m e a s u r i n g m e t h o d s tend to be d e v e l o p e d with this in mind. H o w e v e r , the r e s u l t s are influenced and falsified by a m u l t i t u d e of u n k n o w n methodspecific m e a s u r e m e n t e r r o r s so t h a t the basic a d h e s i o n c a n only be calculated a p p r o x i m a t e l y . This does not, h o w e v e r , m a k e these m e a s u r e m e n t s less v a l u a b l e for p r a c t i c a l applicaicion. Only t h r o u g h the i n t r o d u c t i o n and e x p a n s i o n of m o d e r n i n v e s t i g a t o r y m e t h o d s will it be possible to c a r r y out r e s e a r c h on m o r e c o m p l e x s u r f a c e and i n t e r f a c e processes. At p r e s e n t the difficulty lies in the fact t h a t a g r e a t deal of' i n f o r m a t i o n on the c h e m i c a l c o m p o s i t i o n and g e o m e t r y of the i n t e r f a c e layer, the b o n d i n g e n e r g y b e t w e e n film a t o m s and s u b s t r a t e atoms, the dipole m o m e n t s of a b s o r b e d complexes, the d i s t r i b u t i o n of e l e c t r i c a l conditions, oscillations, s u r f a c e a r e a diffusion and the k i n e t i c s of s o r p t i o n p r o c e s s e s and s u r f a c e r e a c t i o n s is required. A c o m p l e t e a n a l y s i s of t h e s e effects is not possible at present. This m e a n s t h a t only p a r t i a l s o l u t i o n s to the p r o b l e m s of a d h e s i o n can be m a d e

37

while certain limiting conditions are imposed. T h i s g i v e s t h e s c i e n t i s t a w i d e field t o w o r k o n b e f o r e h e c a n e x p l a i n the processes at the interface and deduce from them the laws that could lead to a n i m p r o v e m e n t o f a d h e s i o n . T h o s e w o r k i n g in p r a c t i c a l a p p l i c a t i o n s should develop more sophisticated testing methods which allow the energy a p p l i e d to b e m e a s u r e d e x a c t l y so t h a t it c a n be c o m p a r e d w i t h t h e v a l u e s deduced theoretically.

Acknowledgment

W e w i s h to e x p r e s s o u r g r a t i t u d e to M i s s K. O ' D a y for t r a n s l a t i n g t h i s paper from German.

References

1 J. Kunsemiiller, Meyers Lexikon der Technik und exakten Naturwissenschaften, B.I., Mannheim, 1971. 2 H. Franke, Lexikon der Physik, Franckh'sche Verlagshandlung, Stuttgart, 1969. 3 O.A. Neumiiller, RSmpps Chemie Lexikon, Franckh'sche Verlagshandlung, Stuttgart, 1972. 4 R . J . Good, J. Adhes., 8 (1976) 1; A S T M Definition of Term Relating to Adhesion D 907-70, ASTM, Philadelphia, PA, 1970. 5 K.L. Mittal, J. Adhes., 7 (1974) 377. 6 K . L . Mittal, Electrocomp. Sci. Technol., 3 (1976) 21. 7 D.M. Mattox, Thin Solid Films, 18 (1973) 173. 8 D.M. Mattox, Interface formation and the adhesion of deposited thin films, SC Monogr. R-65 852, 1905 (Sandia Corp.). 9 H . K . Pulker, R. Buhl and E. Moll, Vorabdrucke 9, Plansee Seminar, Reutte, 1977, Band 2, Vortrags nr. 23. 10 J. Strong, A S P Publ., 46 (1934) 18. 11 K . E . Haq, K. H. Behrndt and I. Kobin, J. Vac. Sci. Technol., 6 (1969) 148. 12 R.A. Mc. Kyton and J. J. Wallis, Thin film materials and deposition techniques for infra-red coatings, F A Tech. Rep. 74028, October 1974 (Frankford Arsenal, Philadelphia, PA). 13 E . M . Ruggiero, Proc. 14th Annu. Microelectronics Syrup., St. Louis Section, IEEE, May 24 - 26, 1965, IEEE, New York, 6B-1, 14 S. Bateson, Vacuum, 2 (1952) 365. 15 F. Schlossberger and K. D. Frankson, Vacuum, 9 (1959) 28. 16 D. Davies and B. Whittaker, Metall. Rev., 12 (1967) 15. 17 W.G. Dorfeld, Thin Solid Films, 47 (1977) 241. 18 H. Stuke and K. Wolitz, Beitrag zur Haftung yon PVD-Schichten, Seminar Deutsche

Gesselshaft fi~r Metallkunde, Bad Nauheim, 1977.

19 20 21 22 23 24

A . A . Griffith, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, 221 (1920) 163. H.G. Schneider and S. Meyer, Krist. Tech., 2 (1967) K15. P. Morzek, Wiss. Z. Tech. Hochsch. Karl-Marx-Stadt, 10 (1968) 175. R. Jacobsson and B. Kruse, Thin Solid Films, 15 (1973) 71. G. Katz, Thin Solid Films, 33 (1976) 99. R.B. Belser and W. S. Hicklin, Rev. Sci. Instrum., 27 (1956) 293.

:~

25 26 27 25 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 15 46 47 48 49 50 51 52

53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69

H. Kim and G. Tom andl, ('o~z/. "'Verhundstoy/k'", l)eutsche (;esellseha/t/iir Metallkunde, Kcmstanz, 1976, p. 2(;4. l. Blech, H. Se]lo and L. V. (h'egor, in 1,. 1. Maissel and R. (',hmg (eds.). Hatldbook ~/ Thin Film Teeht~olo~y. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1970, p. 23-1. L. D. Yurk. Adh~'sion o/" E~,aporated Metal Films to Fused Silica, B~I1 Teh,phom' L a b o r a t o r i e s Inc.. Naperville, IL, 1976, pp. 6(), 5.10. J. R. Frederick and K. C, Luch'ma, d. Appl. Phys...5'5 (1964) 256. S. P. Sharma. d. Appl, t)hys.. 47 (1976) 3573. R. J a c o b s s o n . Thin Solid Films. 34 (1976) 191. K. Bhasin. I). B. Jones, S. Shinm'oy mad W. ,l. ,lames, Thitt S(dtd t"ilm,~, ,i;] (1977) 1,t)5 K. Kendall, d. Adhes.. 5 (1973) 77. K. Kendall, d. Phys. I), 4 (1971) l lb6. D. W. Butler. J. Sei. lttstrum., ;1 (1970) 979. D. W. Butler, C. T. H. Stoddart and P. R, Stuart. Aspects Adhes., 6 (1971) 55. C. T. H. Stoddart, D. R. Clarke and C. ,J. Robbie, d. Adhes., 5 (1970) 270. H. H a r r a c h and B, Chapman. Thin Solid Films, 22 (1974) 305. S. Krongelb, in K. L. M ttal (ed.), Adhesiot~ Measurement o/' 7"hit~ b'ih~ls, Thiet~ Films a n d Bulle Coatings, A S T ' M Spee. 7)'ch. Puhl. 6.40. 1978, p. 107. J. L. Vossen. in K, L. Mittal (ed.), Adhesiot~ Measurement o / T h i l z bilms. Thick Films and Bull" Coatings, A S T M Spee. Tech. Publ. 640, 1978, p. 122. J. W. Beams. W. E. Walker and H. S. Morton, Phys. Hey., ,'~'7(1952) 524. J. W. Beams, Selectee, 120 (1954) 619. J. W. Beams, J. B. Breazeale and W. L. Bart, Phys. flee., 100 (1955) 1657 1. R. H u n t s h e r g e r . Off. DIN.. Fed. Soe. Paint Teehnol., 33 (1961) 635. C. Weaver. in G. Kieamel (ed.). Physitc u n d 7k'ehtTik ~,om Sortotio~s- ul~d Desort)tions~,orA~iingen bei Niederet~ Dri)eken. DA(;V. Esch (T~lul]ns). ]96::~. 1 19:/. ). B. N. Chapman, Aspects Adhes., 6 (1971),:13. D. S. Campbell, in L. 1. Maissel and R. Glang (eds.), Handb(~ot~ o/ Thi~ Film Teeh p~olo#4y, McGraw-Hill, New York. 1970, p. 12 1. M. M. Poley and H. L. W h i t t a k e r , d. Vae. Sei. 7Oehnol.. 11 (1974) 114. J. J. Garrido, D. G e r s t e n b e r g and R, W. Berry, Thin Solid Films, 41 (1977) 87. D. S. Lin, d. Phys. D, 4 (1971) 1977. E. T s u n a s a w a , K. Inagagi and K. Y a m a n a k a , ,J. Vae. Sci. 7k'ehttol., 14 (1977) 651. D. M. Mattox. d. Appl. Phys., 37 (1966) 3613. J. O r o s h n i k and J. W. Croll, Thin film a d h e s i o n t e s t i n g by the s c r a t c h method, Surface Seietu'e Syrup.. N e w Me.vie() Seetio~l. Am. Vae. Soe., .3./t)llqlterqtle, N M , A p r i / 22, 1970. O, S. Heavens, J. Phys. R a d i u m , 11 (1950) 355. C. Weaver and R. M. Hill, Philos. Mag., 3 (1958) 1402, C. Weaver and R. M. Hill, Philos. Mag., 8 (1959) 1107. C. Weaver and R. M. Hill, Philos. Mag., 4 (1959) 253. P. B e n j a m i n and C. Weaver, Proc. R. Soc. London, Set. A, 254 (1960) 177. P. B e n j a m i n and C. Weaver, Proe. R. So('. London, Ser. A. 261 (1961) 516. C. Weaver, Chem. Ind. (London). (1965) 370. P. Benjamin and C. Weaver, Proc. R. Soc. London, Set. A. 254 (1960) 163. C. W e a v e r and D. T, P a r k i n s o n , Philos. Mag., 22 (1970) 377. D. W. Butler, C. T. H, Stoddart and P. R. Stuart, d. Phys. D, 3 (1970) 877. J. E. Greene, J. Woodhouse and M. Pestes, Ret,. Sei. lnstrum., ,t5 (1974) 747. J. Hamersky, T h i n Solid Films, 3 (1969) 263. K. L. Chopra, Thin Film Phenomena, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1969, p. 31:t. M. M. K a r n o w s k y and W. B. Estill, Rev. Sei. Instrurn., 35 (1964) 1324. A. J. Perry, Thin Solid Films, 78 (1981) 77:~1 (1981) 357. B. N. Chapman. The adhesion of t h i n films, Ph.D. 77wsis, D e p a r t m e n t of Electrical E n g i n e e r i n g , Imperial College, London, 1969. B. N. Chapman, d. Vae. Sei. Technol., I1 (197-1) 106.

39

70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91

S. Moses and R. K. Witt, Ind. Eng. Chem., 41 (1949) 2338. T. R. Bullet and J. L. Prosser, Prog. Org. Coat., 1 (1972) 45. K. Kendall, J. Adhes., 5 (1973) 179. A. A. Abramov, V. N. Sachko, V. A. Solvov'ev and T. D, Shermergov, Soy. Phys. Solid State, 19 (1976) 1023. S. C. Keeton, Delayed failure in glass, SCL Res. Rep. 7 100 10, 1971 (Sandia Laboratories). R. J, Good, in K. L. Mittal (ed.), Adhesion Measurement of Thin Films, Thick Films and Bulk Coatings, A S T M Spec. Tech. Publ. 640, 1978, p. 18. K. L. Mittal, in K. L. Mittal (ed.), Adhesion Measurement of Thin Films, Thick Films and Bulk Coatings, A S T M Spec. Tech. Publ. 640, 1978, p. 5. J. J. Bikerman, The Science of Adhesive Joints, Academic Press, New York, 2nd edn., 1968. J. J. Bikerman, in L. H. Lee (ed.), Recent Advances in Adhesion, Gordon and Breach New York, 1973, p. 351. R. J. Good, J. Adhes., 2 (1972) 133. G. Irwin, Fracturing of Metals, American Society for Metals, Metals Park, OH, 1947 Trans. Am. Soc. Met., 40 (1948) 147. R. W. Berry, P. M. Hall and M. T. Harris, Thin Film Technology, Van Nostrand, Princeton, NJ, 1968, p. 584. C. Weaver, Faraday Spec. Discuss. Chem. Soc., 2 (1972) 18. G. Dearnley, Appl. Phys. Lett., 28 (1976) 244. C. Weaver, J. Vac. Sci. Technol., 12 (1975) 18. G. J. Zydzig, T. G. Uitert, S. Singh and T. R. Kyle, Appl. Phys. Lett., 31 (1977) 697. H. C. Tong, C. M. Lo and W. F. Traber, J. Vac. Sci. Technol., 13 (1976) 99. L. Holland, The Properties of Glass Surfaces, Chapman and Hall, London, 1964. H. Hieber, Thin Solid Films, 37 (1976) 335. R. Glang, in L. 1. Maissel and R, Glang (eds.), Handbook of Thin Film Technology, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1970, p. 1-22. R. Buhl and H. K. Pulker, Balzers AG, unpublished results, 1977. P. M. Hall, N. T. Panovsis and P. R. Menzel, IEEE Trans. Parts, Hybrids Packag., 11 (1975) 202.

You might also like

- Clifton (1985) Composite DesignDocument16 pagesClifton (1985) Composite DesignlecupiNo ratings yet

- Zeiss Microscopy From The Very BeginningDocument66 pagesZeiss Microscopy From The Very BeginningLaura B.No ratings yet

- Soil Mechanics Property Characterization and Analysis Procedures-Wroth & HoulsbyDocument55 pagesSoil Mechanics Property Characterization and Analysis Procedures-Wroth & HoulsbyAnonymous GnfGTwNo ratings yet

- Settlement of Foundations On Sand and Gravel: J.B. Burland and M.C. BurbidgetDocument62 pagesSettlement of Foundations On Sand and Gravel: J.B. Burland and M.C. BurbidgetPaulo Vinícius MartinsNo ratings yet

- Stress, Deformation, and Martensitic TransformationDocument12 pagesStress, Deformation, and Martensitic TransformationLuiz Fernando VieiraNo ratings yet

- Spurr, 1986, Slender Arch RoofDocument11 pagesSpurr, 1986, Slender Arch Roofprisciliano1No ratings yet

- A Simple Version of The Rathus - 0Document5 pagesA Simple Version of The Rathus - 0Hakimi RizqyNo ratings yet

- Structural Model for Gas-Solid ReactionsDocument8 pagesStructural Model for Gas-Solid ReactionsumarlucioNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 Is 3 D Wave Equation Modeling Feasible in The Next Ten Years - 1989 - Handbook of Geophysical Exploration Seismic ExplorationDocument10 pagesCHAPTER 1 Is 3 D Wave Equation Modeling Feasible in The Next Ten Years - 1989 - Handbook of Geophysical Exploration Seismic ExplorationemarrocosNo ratings yet

- Methods of Seismic Data ProcessingDocument410 pagesMethods of Seismic Data ProcessingAaron Gamboa100% (1)

- NASA Liquid Jet Atomization Study Reveals Effect of Gas Mass VelocityDocument8 pagesNASA Liquid Jet Atomization Study Reveals Effect of Gas Mass VelocityAnonymous WyTCUDyWNo ratings yet

- Effect of Shot-Peening On Surface Crack Propagation in Plane-Bending FatigueDocument8 pagesEffect of Shot-Peening On Surface Crack Propagation in Plane-Bending FatigueaapennsylvaniaNo ratings yet

- Flaw Size Evaluation in Immersed Ultrasonic TestingDocument10 pagesFlaw Size Evaluation in Immersed Ultrasonic TestingR@XNo ratings yet

- Szekely1976 PDFDocument9 pagesSzekely1976 PDFlrodriguez_892566No ratings yet

- Application of Fracture Mechanics to Composite MaterialsFrom EverandApplication of Fracture Mechanics to Composite MaterialsNo ratings yet

- Roger A. Strehlow - Detonation and The Hydrodynamics of Reactive Shock WavesDocument170 pagesRoger A. Strehlow - Detonation and The Hydrodynamics of Reactive Shock WavesGhoree23456No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 0376458380900242 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 0376458380900242 Main陳顥平No ratings yet

- 1.5 Constitutive Laws For Soils From A Physical ViewpointDocument51 pages1.5 Constitutive Laws For Soils From A Physical ViewpointMinhLêNo ratings yet

- Anderson RVBDocument8 pagesAnderson RVBeranu8No ratings yet

- Metallurgical Factors Affecting Fracture Toughness of Aluminum AlloysDocument16 pagesMetallurgical Factors Affecting Fracture Toughness of Aluminum AlloysAlberto Rincon VargasNo ratings yet

- Deflection of Two-Way Reinforced Concrete Systems: State-Of-Theart ReportDocument24 pagesDeflection of Two-Way Reinforced Concrete Systems: State-Of-Theart ReportKaram AlbarodyNo ratings yet

- A Such ThatDocument3 pagesA Such ThatJandfor Tansfg ErrottNo ratings yet

- Ultrasonic Detection of Creep Damage in Catalyst TubesDocument35 pagesUltrasonic Detection of Creep Damage in Catalyst TubesAsep WahyuNo ratings yet

- A Modified Weibull Theory FOR THE: Strength of Granular Brittle MaterialDocument28 pagesA Modified Weibull Theory FOR THE: Strength of Granular Brittle Materialu4sachin3224No ratings yet

- sPE 9467 An in Situ Coal: Ouali Ty Predi CTI Ot'l Teci - Ni QUEDocument9 pagessPE 9467 An in Situ Coal: Ouali Ty Predi CTI Ot'l Teci - Ni QUEpatyrendonNo ratings yet

- 1976 - (Isham) An Introduction To Quantum GravityDocument71 pages1976 - (Isham) An Introduction To Quantum Gravityfaudzi5505No ratings yet

- LUCKY-ELECTRON MODEL FOR CHANNEL HOT ELECTRON EMISSIONDocument4 pagesLUCKY-ELECTRON MODEL FOR CHANNEL HOT ELECTRON EMISSIONWenqi ZhangNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Failure Detection of Circuit BreakersDocument8 pagesMechanical Failure Detection of Circuit BreakersLndr VldNo ratings yet

- Ground deformation mechanism of shield tunneling due to tail void formation in soft clayDocument4 pagesGround deformation mechanism of shield tunneling due to tail void formation in soft clayFederico MalteseNo ratings yet

- A General Method For Determining Resonances in Transformer WindingsDocument8 pagesA General Method For Determining Resonances in Transformer WindingsIlona Dr. SmunczNo ratings yet

- 1968 - Ultimate Strength Analysis of Prestressed Concrete Pressure Vessels - RASHIDDocument11 pages1968 - Ultimate Strength Analysis of Prestressed Concrete Pressure Vessels - RASHIDMarcos Alves da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Minor Elem Hot Crack 3Document1 pageMinor Elem Hot Crack 3nantha kumarNo ratings yet

- The Capacity Design of Reinforced Concrete Hybrid Structures For Multistorey Buildings T. Paulay and W. J. GoodsirDocument17 pagesThe Capacity Design of Reinforced Concrete Hybrid Structures For Multistorey Buildings T. Paulay and W. J. GoodsirFrankie ChanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 General Detection Problems in SFC - 1992 - Journal of Chromatography Library PDFDocument8 pagesChapter 1 General Detection Problems in SFC - 1992 - Journal of Chromatography Library PDFLucas Clementino MouraoNo ratings yet

- Batch Extraction Unit Studies Tar Sand ProcessingDocument9 pagesBatch Extraction Unit Studies Tar Sand ProcessingSiddu RhNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of Flood Levee Reliability: Wood, E.FDocument37 pagesThe Analysis of Flood Levee Reliability: Wood, E.FSebastian AguilarNo ratings yet

- Gupta CH.6-1Document21 pagesGupta CH.6-1Benjamin MullenNo ratings yet

- Awatani 1975Document6 pagesAwatani 1975Ilmal YaqinNo ratings yet

- Passive Fire Protection For Offshore Pipeline RisersDocument15 pagesPassive Fire Protection For Offshore Pipeline RisersvdhivyaprabaNo ratings yet

- A: Multistable Nonlinear Surface ModesDocument9 pagesA: Multistable Nonlinear Surface ModesmenguemengueNo ratings yet

- Characterization of Fracturing Fluids Using RheologyDocument36 pagesCharacterization of Fracturing Fluids Using RheologyShaz MohamedNo ratings yet

- Appraising Earthquake Hypocenter Location ErrorsDocument19 pagesAppraising Earthquake Hypocenter Location ErrorsCésar Augusto Cardona ParraNo ratings yet

- Concawe-The Propagation of NoiseDocument101 pagesConcawe-The Propagation of NoiseICRRecercaNo ratings yet

- THE Trepan or Ring Core Method, Centre-Hole Method, Sach'S Method, Blind Hole Methods, Deep Hole TechniqueDocument34 pagesTHE Trepan or Ring Core Method, Centre-Hole Method, Sach'S Method, Blind Hole Methods, Deep Hole TechniqueDownNo ratings yet

- Buckling: SandiaDocument19 pagesBuckling: SandiamajorikahnNo ratings yet

- Very Low Frequencies Internal Friction Measurements of Ice I HDocument6 pagesVery Low Frequencies Internal Friction Measurements of Ice I Hkannanmech87No ratings yet

- Creep - Investigation To Soil Creep1981 - 01 - 0100Document5 pagesCreep - Investigation To Soil Creep1981 - 01 - 0100TONNY LESMANANo ratings yet

- Biostatics Freework - Abrar SaeedDocument16 pagesBiostatics Freework - Abrar Saeedab JafarNo ratings yet

- Analytical Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy: Selected MethodsFrom EverandAnalytical Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy: Selected MethodsRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Protect Solar CellsDocument25 pagesProtect Solar CellsDINESH SIVANo ratings yet

- National Advisory Committee: AeronauticsDocument43 pagesNational Advisory Committee: AeronauticslavrikNo ratings yet

- Geotube For Marine StructureDocument38 pagesGeotube For Marine StructureWilliam ChongNo ratings yet

- Matejka 1982Document6 pagesMatejka 1982Ly Que UyenNo ratings yet

- AdtjadtjDocument788 pagesAdtjadtjyottanodeNo ratings yet

- Design of GeotubesDocument38 pagesDesign of GeotubesGene Adhiyasa0% (1)

- Field and Laboratory Measurements of Soil Stiffness: Mesure Sur Place Et en Laboratoire de Raideur de SolDocument4 pagesField and Laboratory Measurements of Soil Stiffness: Mesure Sur Place Et en Laboratoire de Raideur de SolLiam CheongNo ratings yet

- Isp 1975 2224802Document16 pagesIsp 1975 2224802Thibault HugNo ratings yet

- Force and Pressure Tests of The Ga (W) - 1 Airfoil PDFDocument98 pagesForce and Pressure Tests of The Ga (W) - 1 Airfoil PDFAndre CoraucciNo ratings yet

- The Direct-Inspection Method in Systems With A Principal Axis of SymmetryDocument4 pagesThe Direct-Inspection Method in Systems With A Principal Axis of Symmetrychm12No ratings yet

- SSP Unit 1Document44 pagesSSP Unit 1kavithavenkatesanNo ratings yet

- UNIT-1 MEC phyDocument15 pagesUNIT-1 MEC phykavithavenkatesanNo ratings yet

- PG TRB Psychology Key Study Materials English Medium Tamilaruvi by Vision TRBDocument6 pagesPG TRB Psychology Key Study Materials English Medium Tamilaruvi by Vision TRBswathiNo ratings yet

- PG TRB Psychology Key Study Materials English Medium Tamilaruvi by Vision TRBDocument6 pagesPG TRB Psychology Key Study Materials English Medium Tamilaruvi by Vision TRBswathiNo ratings yet

- HeatDocument7 pagesHeatkavithavenkatesanNo ratings yet

- Polytechnic TRB - Physics - Unit 3 Study Materials - PDF DownloadDocument28 pagesPolytechnic TRB - Physics - Unit 3 Study Materials - PDF DownloadkavithavenkatesanNo ratings yet

- 14 Differentials Errors and ApproximationsDocument14 pages14 Differentials Errors and ApproximationskavithavenkatesanNo ratings yet

- IC-Applications U4Document21 pagesIC-Applications U4kavithavenkatesanNo ratings yet

- Machinist Hammers and Tools Product ListingDocument34 pagesMachinist Hammers and Tools Product ListingFJH ALZNo ratings yet

- H.M.Abid Yaseen: Metallurgy & Materials EngineerDocument2 pagesH.M.Abid Yaseen: Metallurgy & Materials EngineerTehseen GulNo ratings yet

- Lathe Machine CataloDocument72 pagesLathe Machine CatalodharamvirpmpNo ratings yet

- Green Products and Its CharacteristicsDocument6 pagesGreen Products and Its CharacteristicsRajdeepTanwarNo ratings yet

- Machine Tool Structure Design and AnalysisDocument40 pagesMachine Tool Structure Design and AnalysisPrakash RajNo ratings yet

- Toshiba CodesDocument5 pagesToshiba Codesbruxo70No ratings yet

- Shear Properties of Composite Materials by The V-Notched Beam MethodDocument13 pagesShear Properties of Composite Materials by The V-Notched Beam MethodrsugarmanNo ratings yet

- Calcium Folinate 1734Document3 pagesCalcium Folinate 1734Mulayam Singh YadavNo ratings yet

- Tunnel Lining PDFDocument380 pagesTunnel Lining PDFBryan Armstrong100% (9)

- Hot Rolling TesisDocument284 pagesHot Rolling TesisJoselo HR100% (1)

- dgr10 2020 07 01Document16 pagesdgr10 2020 07 01Data CentrumNo ratings yet

- How To Avoid Cracks in PlasterDocument3 pagesHow To Avoid Cracks in PlasterShativel ViswanathanNo ratings yet

- Bead and MeshDocument7 pagesBead and Meshmuradali01No ratings yet

- Lean Production at Portakabin: HospitalsDocument4 pagesLean Production at Portakabin: HospitalsFLAVIUS222No ratings yet

- FMG 550Document2 pagesFMG 550garciaolinadNo ratings yet

- DS-0035 3W PM2L-3LLx-SD v1.6Document13 pagesDS-0035 3W PM2L-3LLx-SD v1.6Pavan KumarNo ratings yet

- Cement Recruitment Details With Interview Questions: General 0 CommentsDocument42 pagesCement Recruitment Details With Interview Questions: General 0 CommentsAsifRazaNo ratings yet

- Human Skull 3D Papercraft: Paper ArtDocument8 pagesHuman Skull 3D Papercraft: Paper ArtReyes YessNo ratings yet

- Mass Flow MeterDocument158 pagesMass Flow MeterMuhammad Furqan JavedNo ratings yet

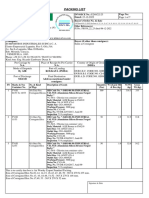

- Packin ListDocument7 pagesPackin ListPedro Z SancheNo ratings yet

- Approach Boundaries NFPA 70E Table 130 2 (C)Document8 pagesApproach Boundaries NFPA 70E Table 130 2 (C)kamal_khan85100% (1)

- Parker Magnetic Particle Inspection Instruments B300, DA400, A210Document4 pagesParker Magnetic Particle Inspection Instruments B300, DA400, A210oquintero99No ratings yet

- Cuptor Rotativ Morello ForniDocument26 pagesCuptor Rotativ Morello ForniscostelNo ratings yet

- URA Elect SR 2005 03Document55 pagesURA Elect SR 2005 03Zhu Qi WangNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Hydraulic ValvesDocument85 pagesChapter 5 - Hydraulic ValvesMuhammad AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Cutting ToolsDocument143 pagesCutting ToolsTone RatanalertNo ratings yet

- Machining Report (Lathe)Document11 pagesMachining Report (Lathe)Syah KlAte67% (3)

- Variable Frequency DriveDocument26 pagesVariable Frequency DriveAshish KatochNo ratings yet

- MakerBot Replicator 2X User ManualDocument64 pagesMakerBot Replicator 2X User Manualrpanther04No ratings yet

- Leather Burnishing & Polishing: Existing ProcedureDocument6 pagesLeather Burnishing & Polishing: Existing ProcedurevinothjohnnashNo ratings yet