Professional Documents

Culture Documents

K of Da

Uploaded by

Derek HilligossCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

K of Da

Uploaded by

Derek HilligossCopyright:

Available Formats

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 1

DA K File

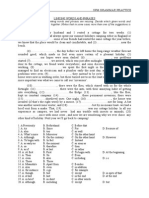

DA K File .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Terror Talk ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Terror Talk ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Terror Talk ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Security ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Security ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Security ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Security ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Disease Security ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Cuomo ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Cuomo ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Kato(1/2) .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Kato(2/2) .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 13 Prolif K .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 14 Prolif K .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Enviro Security ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 16 Genocide Trivialization ........................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Genocide Trivialization ........................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Genocide Trivialization ........................................................................................................................................................................... 19 Genocide Trivialization ........................................................................................................................................................................... 20 AT: Security ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 21 AT: Security ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 22 AT: Terror Talk ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 23 AT: Cuomo .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 24 AT: Kato .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 25

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 2

Terror Talk

The totalizing us-them nature of terrorism discourse prevents effective measures to stop the violence, requiring an infinite mimetic war to win only by problematizing our totalizing view can we prevent endless cycles of violence. Joseba Zulaika, (Professor, Center for Basque Studies), Radical History Review, Issue 85 (winter 2003), ebsco

The events of September 11 are not immune to the possibility that counterterrorism is complicit in creating the very thing it abominates. We mentioned earlier that Sheik Omar, condemned to a New York prison for the rest of his life as the mastermind of the 1993 attack on the WTC, was directly a product of the CIA that recruited him for Reagans anti-Soviet crusade in Afghanistan and gave him visas to come to the United States. The same pattern fits Osama bin Laden and the Taliban. The United States initially trained and armed them. When the Taliban became a pariah regime, the United States main ally in the Arab world, Saudi Arabia, gave them primary support. But the blame game leads us at once into what Slavoj Zizek has labeled the temptation of a double blackmail.21 Namely, either the unconditional condemnation of Third World evil that appears to endorse the ideological position of American innocence, or drawing attention to the deeper sociopolitical causes of Arab extremism, which ends up blaming the victim. Each of the two positions prove one-sided and false. Pointing to the limits of moral reasoning, Zizek resorts to the dialectical category of totality to argue that from the moral standpoint, the victims are innocent, the act was an abominable crime; however, this very innocence is not innocent to adopt such an innocent position in todays global capitalist universe is in itself a false abstraction.22 This does not entail a compromised notion of shared guilt by terrorists and victims; the point is, rather, that the two sides are not really opposed, that they belong to the same field. In short, the position to adopt is to accept the necessity of the fight against terrorism, BUT to redefine and expand its terms so that it will include also (some) American and other Western powers

acts.23 As widely reported at the time, the Reagan administration, led by Alexander Haig, would self-servingly confuse terrorism with communism. 24 As the cold war was coming to an end, terrorism became the easy substitute for communism in Reagans black-and-white world. Still, when Haig would voice his belief that Moscow controlled the worldwide terrorist network, the State Departments bureau of intelligence chief Ronald Spiers would react by thinking that he was kidding.25 By the 1990s, the Soviet Union no longer constituted the terrorist enemy and only days

after the Oklahoma City bombing, Russian president Yeltsin hosted President Clinton in Moscow who equated the recent massacres in Chechnya with Oklahoma City as domestic conflicts. We should be concerned as to what this new Goodversus-Evil war on terror substitutes for. Its consequences in legitimizing the repression of minorities in India, Russia, Turkey, and other countries are all too obvious. But the ultimate catastrophe is that such a categorically ill-defined, perpetually deferred, simpleminded Good-versus-Evil war echoes and re-creates the very absolutist mentality and exceptionalist tactics of the insurgent terrorists. By formally adopting the terrorists own gameone that by definition lacks rules of engagement, definite endings, clear alignments between enemies and friends, or formal arrangements of any sort, military, political, legal, or ethicalthe inevitable danger lies in reproducing it endlessly. One only has to look at the Palestinian-Israeli or the Basque-Spanish conflicts to see how self-defeating the alleged victories against terrorism can be in the absence of addressing the causes of the violence. A war against terrorism, then, mirrors the state of exception characteristic of insurgent violence, and in so doing it reproduces it ad infinitum. The question remains: What politics might be

involved in this state of alert as normal state? Would this possible scenario of competing (and mutually constituting) terror signify the end of politics as we know it?27 It is either politics or once again the self-fulfilling prophecy of fundamentalist crusaders who will never be able

to entirely eradicate evil from the world. Our choice cannot be between Bush and bin Laden, nor is our struggle one of us versus them. Such a split leads us into the ethical catastrophe of not feeling full solidarity with the victims of either sidesince the value of each life is absolute, the only appropriate stance is the unconditional solidarity with ALL victims. 28We must question our own involvement with the phantasmatic reality of terrorism discourse, for now even the USA and its citizens can be regulated by terrorist discourse. . . . Now the North American territory has become the most global and central place in the new history that terrorist ideology inaugurates.29 Resisting the temptation of innocence regarding the barbarian other implies an awareness of a point Hegel made and that applies to the contemporary and increasingly globalized world more than ever: evil, he claims, resides also in the innocent gaze itself, perceiving as it does evil all around itself. Derrida equally holds this position. In reference to the events of September 11, he said: My unconditional compassion, addressed to the victims of September 11, does not prevent me from saying it loudly: with regard to this crime, I do not believe that anyone is politically guiltless.30 In brief, we are all included in the picture, and these tragic events must make us problematize our own innocence while questioning our own political and libidinal investment in the global terrorism discourse.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 3

Terror Talk

Terror rhetoric justifies eradication of populations

Alexander Marcopoulos, J.D. from Tulane, BA in Economics and Philosophy, 2009 (Terrorizing Rhetoric: The Advancement of US Hegemony Through the Lack of a Definition of Terror. http://works.bepress.com/context/alexander_marcopoulos/article/1000/type/native/viewcontent. In (perhaps strategically) failing to provide a static, comprehensive definition of terrorism, the U.S. has been able to construct terrorism as an existential threat in much the same way it constructed the threat of communism during the Cold War. During the Cold War, the U.S. engaged in ideological warfare with the Soviet Union and in doing so, constructed a threat out of all that was related to communism or the Soviets. This nebulous existential threat was not immediately grounded in a fear of invasion or direct harm, but began as a fear of a different ideological system coming to dominate the worlds thought and politics. By implementing the manipulation of fear into its politics, the U.S. was able to supercharge its already dominant position in the world by persuading countries to come under its protective umbrella or else face the threat of communism. This section of the Paper will compare the U.S.s treatment of the word terror to U.S. rhetoric during the Cold War in order to explain the inner-workings of how power is derived from language. The Paper will then proceed to an explanation of how the lack of a static U.S. definition of terror has allowed the Bush Administration to use fear as a political tool. In doing so, it will attempt to draw parallels between the U.S. War on Terror and the Cold War in order to demonstrate how language was used in each to create fear and exert power. In declaring a general War on Terror, President George W. Bush arguably started a cold war of his very own. Just as during the Cold War, the U.S. now finds itself in an era defined by an almost complete commitment of resources to a fight against a vast, unseen and malignant adversary. Both the Cold War and the current U.S. War on Terror are based on the fear of a foreign, ideologically different, and thus unpredictable other. However, instead of a pervasive fear of Soviet communists taking over the world and infiltrating American society, the War on Terror is based on an equally pervasive fear of religious fundamentalists willing to do anything to destroy Western ideals and the Western way of life. In both the Cold War and the current War on Terror, the use of language as a tool of power functioned to create a sense of fear as a vehicle for commanding the formation of policy. Language is most certainly a form of power. While language usually typifies form in the form/content distinction, language also serves to impact content by affecting peoples conceptions of truth. To be able to affect the way people think must have at least some impact on the way people act, if not a tremendous one. By giving meaning to the words people use, he who controls language can alter a persons idea of truth. Though not an act of forceful bullying, the manipulation of language nonetheless constitutes an exertion of power and control. According to French philosopher Michel Foucault: Each society has its regime of truth, its general politics of truth: that is, the types of discourse which it accepts and makes function as true; the mechanisms and instances which enable one to distinguish true and false statements, the means by which each is sanctioned; the techniques and procedures accorded value in the acquisition of truth; the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true. While Foucault speaks primarily of governments and those in positions of dominance exerting control over individual people, his characterization of the effect of shaping truth is applicable in the context of nation states. By equating the word communism with godlessness and malevolence, Americans during the Cold War turned a clash of ideology into a fight between good and evil. In this way, the dominant voice in American politics gave no meaning to the word communism and thereby constructed peoples conceptions of the truth regarding that word. Much like the Cold War, the War on Terror employs a logic that labels people and groups in a way that characterizes them as categorically evil. By invoking the word terror, a word that has come to connote evil, U.S. policymakers have been able to create an element of fear sufficient to justify the eradication of those people or groups it terms terrorist. Fear created by language that operates in that regard is a political commodity [that] has no practical limits. During the Cold War, fear was used to influence people to support the U.S., or else face losing their freedom to the spread of communism. Termed the red scare, this tactic involved the use of rhetoric through propaganda campaigns to draw a line between the righteous, moral self (the United States), and the evil, godless other (the Soviet Union). To the Western world, Soviet leaders, citizens, and organizations lost their identity as such and came to be seen only as communists. Their mere existence was constructed as a threat through the rhetoric of U.S. policymakers. In a highly effective, albeit twisted fashion, the U.S. was thus able to maintain its hegemony, as it could justify policies of expansion, including the stationing of U.S. troops abroad, the formation of certain alliances, and the participation in foreign wars all in the name of containing communism. Whereas the word communism functioned as a trump card in justifying U.S. action during the Cold War, the word terror has come to serve U.S. policy in the U.S. War on Terror in quite the same way. During the Cold War, the U.S. employed a policy whereby it targeted communism as an existential threat. In doing so, the U.S. justified the exertion of its influence (militarily and otherwise) in almost every region of the world. It is by such means that the U.S. engaged in conflicts in North Korea and Vietnam and provided economic assistance to Eastern European nations through programs such as the Marshall Plan. In a like manner, the U.S. has recently used its vague,

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 4

Terror Talk

definition-less concept of terror to link the existential threat of terrorism to what it refers to as rogue states in projecting its power globally. Perhaps the best example of this power projection lies in U.S. influence over Southeast Asia following the September 11, 2001 terror attacks. The U.S. employed its almost limitless War on Terror to act as a hegemon in Southeast Asia in a few ways. First, just as it did so elsewhere, the U.S. pushed hard for support from nations in Southeast Asia in carrying out its anti-terror operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. By not having a static definition of terror, the U.S. arguably made it apparent to the nations it approached that failure to cooperate could mean the risk of being labeled terrorist, and then being targeted as such. Additionally, the invocation of the word terror also led to an exertion of hard power hegemony by the U.S. in Asia, as the U.S. increased its military presence there in order to contain and eradicate groups in the region that it deemed terrorist. As submitted above, the lack of a definition of terror has given the U.S. much latitude in engaging in the practice of labeling certain groups as terrorist according to its strategic needs. Finally, the U.S. used that same tactic to take the lead as a soft power hegemon in eliciting the cooperation of ASEAN member states in rooting out terrorist organizations in Southeast Asia. There is no reason to believe that the coalitionbuilding initiatives discussed by the coming Obama Administration will not use the word terror to garner support for, e.g. operations in Afghanistan, in like fashion. The absence of a static U.S. definition of terror is the key vehicle for the U.S. to employ the politics of fear in its War on Terror. There are a few critical reasons why this is true. First of all, people often exhibit an innate fear of the unknown. Without a definitive, concrete archetype establishing what constitutes a terrorist act and what does not, there is a certain mystery created around the terrorist. The construction of the terrorist as the unknown other provides an incentive for countries to jump on the U.S.s bandwagon against terrorism, as it gives them an opportunity to define themselves as coherent and righteous versus the incoherent, immoral terrorist other. The U.S. employed the same tactic during the Cold War, as it characterized the Soviet Union as an evil empire and invited other countries to support it in a system of alliances pitting the capitalist, morally-upright, free world against the idea of communism. This approach was effective in terms of establishing a sphere of influence during the Cold War and appears to be so in the context of the War on Terror, as evidenced by the quickness with which the international community allowed UN Security Council Resolution 1373 to pass.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 5

Security

The Negatives Discussion of International Relations, War and Violence is Imbued With the Metaphysical Concept of SecuritySpeaking this Discourse Brings With it the Assumptions of Violence Inherent in Contemporary Politics

Dillon 96 (michael, senior lecturer in politics and international relations at the university of lancaster, the politics of security, p.13-4) There is a preoccupation, which links both the beginning and the end of metaphysics, and so also the beginning and the end of metaphysical politics. It is something, which, because it furnishes the fundamental link between politics and metaphysics, affords me my entry into the relationship, which obtains between them. That something is security. If the question of the political is to be recovered from metaphysical thinking, therefore, then security has to be brought into question first. Security, of course, saturates the language of modern politics. Our political vocabularies reek of it and our political imagination is confined by it. The hypocrisy of our rulers (whosoever 'we' are) consistently hides behind it. It would, therefore, be an easy task to establish that security is the first and foundational requirement of the State, of modern understandings of politics, and of International Relations, not only by reference to specific political theorists but also by reference to the discourses of States. But I want

to explore the thought that modern politics is a security project for reasons which are antecedent to, and account for, the axioms and propositions of (inter)national political theorists, the platitudes of political discourse, and the practices of States, their political classes and leaders. Consequently, to conceive of our politics, as a politics of security is not to advance a view held by particular thinkers or even by particular disciplines. It is to draw attention to a necessity (which Heidegger's history of metaphysics will later allow us to note and explore) to which all thinkers of politics in the metaphysical tradition are subject. In pursuing this thought it

security turns-out to have a much wider register - has always and necessarily had a much wider register, something which modern international security studies have begun to register - than that merely of preserving our so-called basic values, or even our mortal bodies. That it has, in fact, always been concerned with securing the very grounds of what the political itself is; specifying what the essence of politics is thought to be. The reason is that the thought within which political thought occurs - metaphysics-and specifically its conception of truth, is itself a security project, For metaphysics is a tradition of thought defined in terms of the pursuit of security: with the securing, in fact of a secure arche, determining principle, beginning or ground, for which its under-standing of truth and its quest for certainty calls. Security, then, finds its expression as the principle, ground or arche - for which metaphysical thought is a search - upon which something stands, pervading and guiding it in its whole structure and essence.

follows that Hence, as Leibniz wrote: If one builds a house in a sandy place, one must continue digging until one meets solid rock or firm foundations; if one wants to unravel a tangled thread one must look for the beginning of the thread; if the greatest weights are to be moved, Archimedes demanded only a stable place. In the same way, if one is to establish the elements of human knowledge some fixed point is required, on which we can safely

metaphysics first allows security to impress itself upon political thought as a self-evident condition for the very existence of life - both individual and social. One of those impulses which it is said appears like an inner command to be instinctive (in the form, for, of the instinct for survival), or axiomatic (in the form of the principle of self-preservation, the right to life, or the right to self defense), security thereby became the value which modern understandings of the political and modern practices of politics have come to put beyond question, precisely because they derived its very requirement from the requirements of metaphysical truth itself. In consequence, security became the predicate upon which the architectonic political discourses of modernity were constructed; upon which the vernacular architecture of modern political power, exemplified in the State, was based; and from which the institutions and practices of modern (inter)national politics,

rest and from which we can set out without fear. (emphasis added) It is for this reason, therefore, that including modern democratic politics, ultimately seek to derive their grounding and foundational legitimacy. Thus, for example, and in a time other than our own, the security of an ecumene of belief in the ground of a divinely ordained universe promising salvation for human beings - something that, constituting the Christian Church, provided an ideal of community which continues to pervade the Western tradition -insisted: extra ecclesjam nulla salus' (no salvation outside the Church). Salvation was the ultimate form of spiritual security. And that security was to be acquired through being gathered back into where we belong; a belonging, in other words, to God. What is crucial here is not what happens to us after death, but salvation as the expression of the longing for the return to a pure and unadulterated form of belonging; a final closing-up of the wound of existence by returning to a lost oneness that

. The outcome of this project was a rejection of the world through the constitution of an ideal world which - not least because of the model it offered, the resentment which it fostered and the economy of salvation and cruelty which it instantiated - acted in the world to constitute a form of redeeming politics. In a way that indicates the continuity of the metaphysical tradition, however, this slogan can be, and was, easily adjusted to furnish the defining maxim of modern politics: no security outside the State; no State without security. And this, in its turn, has given rise to powerful forms of what I would call the disciplinary politics of Hobbesian thought and the actuarial politics of technologies thought. Each of these is also concerned to specify the principle, ground or rule that would satisfy the metaphysically sequestered compulsion for security: thus relieving human beings of the dilemmas and challenges it faces to discover, in its changing circumstances, what it is to be - to act and live - as humans. The basic thought to be pursued is one which, in simultaneously drawing both our current politics and our tradition of political

never was. The reverse of Cyprian's dictum was, of course, equally true. No Church without salvation thought into question by challenging their mutual foundation in security, serves, in addition, to illustrate and explore some important aspects of the political implications of Heidegger's thought. My thought, then, is that modern

politics is a security project in the widest possible - ontological - sense of the term because it was destined to become so by virtue of the very character or nature of the thinking of truth within which, through which, and by continuous and intimate reference to which, politics itself has always been thought. What is at issue first of all, for me, therefore, is not whether one says yes or no to our modern (inter)national regimes of security, but what Foucault would have called the overall discursive fact that security is spoken about at all, the way in which it is put into political discourse and how it circulates throughout politics and other discourses. I think Heidegger's account of meta physics provides a means of addressing that fundamental question. <P 13-14>

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 6

Security

We Must Not Ignore These Questions About SecurityContinuation of the Status Quo Politics Risks the Totality of Violence and Human Extinction

DILLON IN 96 (MICHAEL, SENIOR LECTURER IN POLITICS AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF LANCASTER, THE POLITICS OF SECURITY) To put it crudely, and ignoring for the moment Heidegger's so-called `anti humanist' (he thought 'humanism' was not uncannily human enough) hostility to the anthropocentrism of Western thought. As the real prospect of human species extinction is a function of how human beinq has come to dwell in the world, then human beinq has a pressinq reason to reconsider, in the most originary way possible, notwithstanding other arguments that may be advanced for doing so, the derivation of its understandinq of what it is to dwell in the world, and how it should comport itself if it is to continue to do so. Such a predicament ineluctably poses two fundamental and inescapable questions about both Philosophy and politics back to philosophy and politics and of the relation between them: first, if such is their end, what must their oriqins have been? Second, in the midst of all that is, in Precisely what does the creativity of new beqinninqs inhere and how can it be preserved, celebrated and extended? No matter how much we may want to elide these questions, or, alternatively, provide a whole series of edifying answers to them, human beinqs cannot iqnore them, ironically, even if they remain anthropocentric in their concerns, if they wish to survive. Our present does not allow it. This ioint reqress of the philosophical and the political to the very limits of their thinking and of their possibility therefore brinqs the question of Beinq (which has been the question of philosophy, even though it has always been directed towards beings in the answers it has offered) into explicit coniunction with the question of the political once more throuqh the attention it draws to the ontoloqical difference between Beinq and beinqs, and emphasises the abidinq reciprocity that exists between them. We now know that neither metaphysics nor our politics of security can secure the security of truth and of life which was their reciprocatinq raison d'66tre (and, raison d'etat). More importantly, we now know that the very will to security the will to power of sovereiqn presence in both metaphysics and modern politics - is not only a prime incitement to violence in the Western tradition of thouqht, and to the qlobalisation of its (inter)national palitics, but also self-defeatinq; in that it does not in its turn merely endanqer, but actually enqenders danqer in response to its own discursive dynamic. One does not have to be persuaded of the destinal sendinq of Beinq, therefore, to be persuaded of the profundity - and of the profound danqer- of this the modern human condition.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 7

Security

Discourses of Security Necessarily Invoke Their OppositeThe Logic of Violence Proposes a Perpetual Counter-Violence and Insecurity Which Makes the Affirmative Harms Simply a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

CHERNUS, PROFESSOR OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO AT BOULDER, 2K1 Ira, Israel and the United States: Fighting Terror in the National Insecurity http://spot.colorado.edu/~chernus/SinceSeptember11.htm State,

In this sense, too, the U.S. is in Israels shoes. Both are entrenched in the logic of the insecurity state. That logic flows from two fundamental principles: there is a mortal threat to the very existence of our nation, and our own policies play no role in generating the threat. If our nation bears no responsibility, then we are powerless to eradicate the threat. There is no hope for a truly better world, nor for ending the danger by mutual compromise with "the other side." The threat is effectively eternal. The best to hope for is to hold the threat forever at bay. Yet the sense of powerlessness is oddly satisfying, because it preserves the conviction of innocence: if our policies are so ineffectual, the troubles of the world can hardly be our fault. And the vision of an endless status quo is equally satisfying, because it promises to prevent historical change. If peril is permanent, the world is an endless reservoir of potential enemies. Any fundamental change in the status quo portends only catastrophe. The only path to security, it seems, is to prevent change by imposing control over others. When those others fight back, the national insecurity state sees no reason to re-evaluate its policies; that would risk the change it seeks, above all, to avoid. So it can only meet violence with more violence, while protesting its innocence. Of course, the inevitable frustration is blamed on the enemy, reinforcing the sense of peril and the demand for absolute control through violence. The goal of total control is self-defeating; each step toward security becomes a source of, and is taken as proof of, continuing insecurity. This makes the logic of the insecurity state viciously circular. Why are we always fighting? Because we always have enemies. How do we know we always have enemies? Because we are always fighting. And knowing that we have enemies, how can we afford to stop fighting? In the insecurity state, there is no way to talk about security without voicing fears of insecurity, no way to express optimism without expressing despair. On every front, it is a self-fulfilling prophecy; a self-confirming and self-perpetuating spiral of violence; a trap that seems to offer no way out.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 8

Security

Voting aff solves rejecting security discourse allows for the recreation of politics

DILLON 96 (MICHAEL, SENIOR LECTURER IN POLITICS AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF LANCASTER, THE POLITICS OF SECURITY) Reimagining politics is, of course, easier said than done. Resistance to it - especially in International Relations nonetheless gives us a clue to one of the places where we may begin. For although I think of this project as a kind of political project, resistance to it does not arise from a political conservatism. Modern exponents of political modernity pride themselves on their realistic radicalism. Opposition always arises, instead, from an extraordinarily deep and profound conservatism of thought. Indeed, conservatism of thought in respect of the modern political imagination is required of the modern political subject. Remaining politics therefore means thinking differently. Moreover, the project of that thinking differently leads to thinking 'difference' itself. Thought is therefore required if politics is to contribute to out-living the modern; specifically, political thought. The challenge to out-live the modern issues from the faltering of modern thought, however, and the suspicion now of its very own project of thought, as much as it does from the spread of weapons of mass destruction, the industrialization and ecological despoliation of the planet, or the genocidal dynamics of new nationalisms. The challenqe to out-live the modern issues, therefore, from the modern condition of both politics and thouqht. This so- called suspicion of thouqht - I would rather call it a transformation of the project of thought which has disclosed the faltering of the modern project of thought - is what has come to distinguish continental thouqht in the last century. I draw on that thouqht in order to think the freedom of human beinq aqainst the defininq political thouqht of modernity: that ontoloqical preoccupation with the subject of security which commits its politics to securinq the subiect. Motivated therefore, by a certain sense of crisis in both philosophy and politics, and by the conviction that there is an intimate relation between the two which is most violently and materially exhibited globally in (inter)national politics, the aim of this book is to make a contribution towards rethinking some of the fundamentals of International Relations through what I would call the political philosophy of contemporary continental thought. Its ultimate intention is, therefore, to make a contribution toward the reconstruction of International Relations as a site of political thouqht, bv departinq from the very commitment to the politics of sublectivity upon which International Relations is premised. This is a tall order, and not least because the political philosophy of continental thought cannot be brought to bear upon International Relations if the political thought of that thought remains largely unthought. <P 2>

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 9

Disease Security

Disease discourse results in dangerous securitization.

Dr. Stefan Elbe, University of Sussex (UK), 2005, AIDS, Security, Biopolitics, International Relations, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 403-419, http://ire.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/19/4/403 (Google Scholar)

This biopolitical axis of biopower is extremely pertinent for understanding the deeper significance of the ongoing securitization of AIDS, for a crucial implication of the rise of European biopolitics was that henceforth disease would be rendered an important political and economic issue needing to be collectively resolved as a matter of overall policy.22 If one of the goals of biopolitics is to maximize the health of populations, then disease could no longer be left to the random fluctuations of nature, but would have to be brought under continuous political and social control, which, according to Foucault, is precisely what happened in 18th-century Europe. The 18th century, to be sure, did not invent health measures as such (there are many historical precedents for this), but it prescribed new rules and above all transposed the practice onto an explicit, concerted level of analysis such as had been previously unknown.23 From this time onwards, the social, economic, and political problems posed by disease have occupied an expanding place in European politics. Today such biopolitical impulses can also be found resonating beyond the borders of Europe through practices such as the securitization of HIV/AIDS. The latter, after all, marks nothing other than a powerful international intervention targeted directly at the level of population. With the arrival of HIV/AIDS on the international security agenda, security is no longer confined to defending sovereignty, territorial integrity, and international law; but, as the unprecedented Security Council meeting demonstrates, population dynamics including levels of disease have now become strategically significant as well. International political actors securitizing HIV/AIDS are effectively calling upon governments around the world to make the health and longevity of their populations a matter of highest governmental priority echoing Foucaults earlier observation that in a biopolitical age [t]he population now appears more as the aim of government than the power of the ruler.24 The securitization of AIDS is also biopolitical, secondly, because of the manner in which international actors are trying to monitor and govern the health of populations. The detailed statistical monitoring of populations that formed such an integral component of 18th-century European biopolitics is today being replicated on a global level by international agencies eager to identify and forecast the population dynamics likely to be induced around the world by HIV/AIDS. The task of compiling these statistics has been assigned to the World Health Organization and the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). The latter prides itself on its efforts to provide strategic information about HIV/AIDS globally, as well as [t]racking, monitoring and evaluation of the epidemic and of responses to it.25 Indeed, it claims to be the worlds leading resource for epidemiological data on HIV/AIDS.26 To this end, UNAIDS also provides in a manner that recalls Englands 19th-century Blue Books annual updates on the global state of the AIDS pandemic, and endeavours to keep up-to-date information on HIV prevalence amongst adult populations for every country.27 Crucially, UNAIDS does not restrict itself to providing data for collective populations; its surveillance techniques penetrate further and also generate new sub-populations by singling out specific risk groups that need to be targeted another historical hallmark of biopolitics.28 The organization thus differentiates between adult and child populations and between urban and rural populations, and pays particularly close attention to sex workers and drug users. Where possible, UNAIDS even gathers data on sexual behaviour, such as the median age of first sexual intercourse and the rate of condom use, as well as a variety of other knowledge indicators. UNAIDS, in short, produces the vital knowledge about the biological characteristics of the worlds populations and sub-populations needed to rein in the pandemic. Finally, the linking of international security and HIV/AIDS is also characteristically biopolitical in that it is undertaken with the active and willing participation of a whole host of wider social and political actors. In his essay on The Politics of Health in the Eighteenth Century, Foucault observed how biopower and biopolitics were not merely deployed vertically downwards from the state into society, but were consentingly invoked by many social groups, including religious associations such as the Quakers, charitable organizations, and even scholars. The health of all, he noted, became a priority for all,29 which is why Foucault insisted that biopower must be analysed as something which circulates, or rather as something which only functions in the form of a chain, and which is exercised through a net-like organisation.30 The unfolding of the securitization of AIDS follows such a net-like deployment of biopower, as it is being simultaneously driven by a plethora of actors ranging from: (i) predominantly Western governments including the United States; (ii) international organizations such as the World Health Organization, the United Nations, the European Union, ASEAN, and the African Union; (iii) a plethora of prominent multinational corporations working through the Global Business Coalition on HIV/AIDS; (iv) non-governmental organizations such as the Civil Military Alliance to Combat HIV/AIDS and the International Crisis Group; (v) think tanks such as the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Chemical and Biological Arms Control Institute; (vi) media organizations; and (vii) scholars in the academy.31 The net of the securitization of AIDS has thus been widely cast, corroborating Foucaults view that biopower is never solely the property of one agent; it is always plural, decentralized, and capillary in nature. Power, he reminded his readers, is everywhere; not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere.32 In the end, these biopolitical dimensions to the securitization of HIV/AIDS also make it far less surprising that Foucaults influential description of the 18th-century biopolitical transformation in Europe could just as well be read as a penetrating commentary on the contemporary expansion of the international security agenda to include health issues such as AIDS: For the first time in history, no doubt, biological existence was reflected in political existence; the fact of living was no longer an inaccessible substrate that only emerged from time to time, amid the randomness of death and its fatality; part of it passed into knowledges field of control and powers sphere of intervention. Power would no longer be dealing simply with legal subjects over whom the ultimate dominion was death, but with living beings, and the mastery it would be able to exercise over them would have to be applied at the level of life itself; it was the taking charge of life, more than the threat of death, that gave power its access even to the body.33 In this case, however, the securitization of HIV/AIDS takes on particular significance for contemporary world politics not only because it is a novel way of framing the illness, but also because it illustrates how international security constitutes an important site for disseminating biopolitical strategies to the non-Western world giving rise to novel normative dangers.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 10

Cuomo

The dis ads Construction of War Relies on the Assumption that There is and Should Be an Ethical Distinction Between War and Non-WarThis Ignores Militarism and Legitimates Structural Violence

Chris Cuomo, War Is Not Just an Event: Reflections on the Significance of Everyday Violence, Hypatia 11.4, 1996, p. 30-46 (http://www.ccuomo.org/War23.htm) Just war theory is a prominent example of a philosophical approach that rests on the assumption that wars are isolated from everyday life and ethics. Such theory, as developed by St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, and Hugo Grotius, and as articulated in contemporary dialogues by many philosophers, including Michael Walzer (1977), Thomas Nagel (1974), and Sheldon Cohen (1989 ), take the primary question concerning the ethics of warfare to be about when to enter into military conflicts against other states. They therefore take as a given the notion that war is an isolated, definable event with clear boundaries. These boundaries are significant because they distinguish the circumstances in which standard moral rules and constraints, such as rules against murder and unprovoked violence, no longer apply. Just-war theory assumes that war is a separate sphere of human activity having its own ethical constraints and criteria and in doing so it begs the question of whether or not war is a special kind of event, or part of a pervasive presence in nearly all contemporary life. Because the application of just-war principles is a matter of proper decision-making on the part of agents of the state, before wars occur, and before military strikes are made, they assume that military initiatives are distinct events. In fact, declarations of war are generally overdetermined escalations of preexisting conditions. Just-war criteria cannot help evaluate military and related

institutions, including their peacetime practices and how these relate to wartime activities, so they cannot address the ways in which armed conflicts between and among states emerge from omnipresent,

The remarkable resemblances in some sectors between states of peace and states of war remain completely untouched by theories that are only able to discuss the ethics of starting and ending direct military conflicts between and among states. Applications of just-war criteria actually help create the illusion that the "problem of war" is being addressed when the only considerations are the ethics of declaring wars and of military violence within the boundaries of declarations of war and peace. Though just-war considerations might theoretically help decision-makers avoid specific gross eruptions of military violence, the aspects of war which require the underlying presence of militarism and the direct effects of the omnipresence of militarism remain untouched. There may be important decisions to be made about when and how to fight war, but these must be considered in terms of the many other aspects of contemporary war and militarism that are significant to nonmilitary personnel, including women and nonhumans

often violent, state militarism.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

10

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 11

Cuomo

Ignoring Structural Violence in Favor of Discrete Conflicts Maintains Privilege and Distracts Resistance From All Other Forms of Violence, The Plan Will Lock Us in to the Question of War to Ignore The Other Dangers to the Community they Support

Chris Cuomo, War Is Not Just an Event: Reflections on the Significance of Everyday Violence, Hypatia 11.4, 1996, p. 30-46 (http://www.ccuomo.org/War23.htm) Ethical approaches that do not attend to the ways in which warfare and military practices are woven into the very fabric of life in twenty-first century technological states lead to crisis-based politics and analyses. For any feminism that aims to resist oppression and create alternative social and political options, crisis-based ethics and politics are problematic because they distract attention from the need for sustained resistance to the enmeshed, omnipresent systems of domination and oppression that so often function as givens in most people's lives. Neglecting the omnipresence of militarism allows the false belief that the absence of declared armed conflicts is peace, the polar opposite of war. It is particularly easy for those whose lives are shaped by the safety of privilege, and who do not regularly encounter the realities of militarism, to maintain this false belief. The belief that militarism is an ethical, political concern only regarding armed conflict, creates forms of resistance to militarism that are merely exercises in crisis control. Antiwar resistance is then mobilized when the "real" violence finally occurs, or when the stability of privilege is directly threatened, and at that point it is difficult not to respond in ways that make resisters drop all other political priorities. Crisis-driven attention to declarations of war might actually keep resisters complacent about and complicitous in the general presence of global militarism. Seeing war as necessarily embedded in constant military presence draws attention to the fact that horrific, state-sponsored violence is happening nearly all over, all of the time, and that it is perpetrated by military institutions and other militaristic agents of the state. Moving away from crisis-driven politics and ontologies concerning war and military violence also enables consideration of relationships among seemingly disparate phenomena, and therefore can shape more nuanced theoretical and practical forms of resistance. For example, investigating the ways in which war is part of a presence allows consideration of the relationships among the events of war and the following: how militarism is a foundational trope in the social and political imagination; how the pervasive presence and symbolism of soldiers/warriors/patriots shape meanings of gender; the ways in which threats of state-sponsored violence are a sometimes invisible/sometimes bold agent of racism, nationalism, and corporate interests; the fact that vast numbers of communities, cities, and nations are currently in the midst of excruciatingly violent circumstances. It also provides a lens for considering the relationships among the various kinds of violence that get labeled "war." Given current American obsessions with nationalism, guns, and militias, and growing hunger for the death penalty, prisons, and a more powerful police state, one cannot underestimate the need for philosophical and political attention to connections among phenomena like the "war on drugs," the "war on crime," and other state-funded militaristic campaigns.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

11

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 12

Kato(1/2)

QuickTime and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are need ed to see this picture.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

12

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 13

Kato(2/2)

QuickTime an d a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are need ed to see this p icture .

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

13

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 14

Prolif K

The DA impacts use racist Orientalist discourse that assumes that the West is rational and disciplined while Third World countries are uncultivated and cannot be trusted with nuclear weapons.

Gusterson Prof. Antro. MIT 99 [Hugh, Associate Professor of Anthropology and Science and Technology Studies at MIT, "Nuclear Weapons and the Other in the Western Imagination," Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 1, (Feb., 1999), pp. 1 1 1- 143, http://www.jstor.org/stable/65653l,] The dominant discourse that stabilizes this system of nuclear apartheid in Western ideology is a specialized variant within a broader system of colonial and postcolonial discourse that takes as its essentialist premise a profound Otherness separating Third World from Western countries.6 This inscription of Third World (especially Asian and Middle Eastern) nations as ineradicably different from our own has, in a different context, been labeled "Orientalism" by Edward Said ( 1 978). Said argues that orientalist discourse constructs the world in terms of a series of binary oppositions that produce the Orient as the mirror image of the West: where "we" are rational and disciplined, "they" are impulsive and emotional; where "we" are modem and flexible, "they" are slaves to ancient passions and routines; where "we" are honest and compassionate, "they" are treacherous and uncultivated. While the blatantly racist orientalism of the high colonial period has softened, more subtle orientalist ideologies endure in contemporary politics. They can be found, as Akhil Gupta ( 1 998) has argued, in discourses of economic development that represent Third World nations as child nations lagging behind Western nations in a uniform cycle of development or, as Lutz and Collins ( 1 993) suggest, in the imagery of popular magazines, such as National Geographic. I want to suggest here that another variant of contemporary orientalist ideology is also to be found in U.S. national security discourse.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

14

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 15

Prolif K

The discourse of your authors legitimizes domination of the Third World in an effort to prop up the western nuclear monopoly. Separating "their" problems from "ours" is a false distinction rooted in racism and orientalism.

Gusterson Prof. Antro. MIT 99 [Hugh, Associate Professor of Anthropology and Science and Technology Studies at MIT, "Nuclear Weapons and the Other in the Western Imagination," Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 1, (Feb., 1999), pp. 1 1 1- 143, http://www.jstor.org/stable/65653l,] The discourse on nuclear proliferation legitimates this system of domination while presenting the interests the established nuclear powers have in maintaining their nuclear monopoly as if they were equally beneficial to all the nations of the globe. And, ironically, the discourse on nonproliferation presents these subordinate nations as the principal source of danger in the world. This is another case of blaming the victim. The discourse on nuclear proliferation is structured around a rigid segregation of "their" problems from "ours." In fact, however, we are linked to developing nations by a world system, and many of the problems that, we claim, render these nations ineligible to own nuclear weapons have a lot to do with the West and the system it dominates. For example, the regional conflict between India and Pakistan is, in part at least, a direct consequence of the divide-and-rule policies adopted by the British raj; and the dispute over Kashmir, identified by Western commentators as a possible flash point for nuclear war, has its origins not so much in ancient hatreds as in Britain's decision in 1846 to install a Hindu maharajah as leader of a Muslim territory (Bums 1 998). The hostility between Arabs and Israelis has been exacerbated by British, French, and American intervention in the Middle East dating back to the Balfour Declaration of 1917. More recently, as Steven Green points out, "Congress has voted over $36.5 billion in economic and military aid to Israel, including rockets, planes, and other technology which has directly advanced Israel's nuclear weapons capabilities. It is precisely this nuclear arsenal, which the U.S. Congress has been so instrumental in building up, that is driving the Arab state to attain countervailing strategic weapons of various kinds" ( 1 990).

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

15

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 16

Enviro Security

The idea of humanity being separate from nature allows the creation of "environment" being anything that needs to be securitized by the international system without question.

QuickTime and a decompressor are neede d to see this picture.

areuneeded toandthispicture. Qunn imeand ath picture. areickTpressor aa ispicture. decomimesee th QickTpressor see is areeeded toand decomim tosee QickTpressor u eeded decome

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

16

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 17

Genocide Trivialization

Trivialization of genocide allows for the continuation of such atrocities.

Alexandre Kimenyi, Journalist for The Edwin Mellen Press. 2002 TRIVIALIZATION OF GENOCIDE: THE CASE OF RWANDA. http://www.kimenyi.com/trivilization-of-genocide-the-case-ofrwanda.php This trivialization was started by the Clinton administration which refused to call it genocide. The State Department officials were instructed not to utter the word genocide in the Tutsi killings in Rwanda but use "acts of genocide" instead. This was motivated, apparently, by the fact that the administration understood the legal, political and moral implications of the acceptance of this term as signatory of UN Geneva Convention on Genocide. Had it admitted that genocide was taking place, The United States, the only superpower today, would have to intervene immediately to stop it . It thus refused to utter the word because the physical extermination of Tutsi in Rwanda did not jeopardize US interests. The trivialization of Tutsi genocide is epitomized by many individuals and organizations who preach forgetting, forgiveness and reconcialiton as the only viable solution to post-genocide Rwanda. Christophe Mitterand, Franois Mitterand's son who was responsible for African Department during his father's government, has also categorically denied that Tutsi genocide took place. "Massacres, yes, but genocide, no," he said. (12) III. Justification and rationalization of genocide All attempts to jusfify and rationalize genocide in Rwanda by social scientists and others not only trivialize genocide, but also do they condone it because doing so removes the responsibility and minimizes this despicable act. Genocide is seen as either a self-defense reaction, a natural behavior in this dog-eat-dog world, a continuation of the Hutu Revolution and an attempt to get rid of evil.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

17

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 18

Genocide Trivialization

Use of the term genocide to gain shock value trivializes the violence that actually occurs.

Alain Destexhe. Belgian Politician and Author. 1995. Rwanda and genocide in the twentieth century Consequently the word 'genocide' has often been used when making comparisons with later massacres throughout the world in order to attract attention by evoking images of the concentration camps and their victims. The Second World War and the genocide became absolute references in the political context. As Alain Finkielkraut puts it, 'Satan became incarnate in the person of Hitler who represented nothing less than an allegory for the devil.' Fascism became the supreme enemy and all political adversaries were indiscriminately accused of supporting it. But it was genocide that became the ultimate verbal stigma, a term used both to describe any thoroughly horrendous, thoroughly fascist act perpetrated by an enemy and as a rallying call for minority groups looking to assert their identity and legitimise their existence. Thus the word genocide fell victim to a sort of verbal inflation, in much the same as happened with the word fascist. It has been applied freely and indiscriminately to groups as diverse as the blacks of South Africa, Palestinians and women, as well as in reference to animals, abortion, famines and widespread malnutrition, and to many other situations. The term genocide has progressively lost its initial meaning and is becoming dangerously commonplace. In order to attention to contemporary situations of violence or injustice by making comparisons with murder on the greatest scale known in this century, 'genocide' has been used as synonymous with massacre, oppression and repression, overlooking that what lies behind the image it evokes is the attempted annihilation of the entire Jewish race. One of the aims of this book is to restore the specific meaning to a term which has been so much abused that it has become the victim of its own success. Further thvialisation has resulted from the over-use of the term 'Holocaust', first popularised on a wide scale in the 1970s by the American television series with that title. The original context is of course religious and means, literally, 'a ritual sacrifice wholly consumed by fire'. The use of this term has a twofold effect, both mystifying and spectacular, which distorts and denies reality.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

18

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 19

Genocide Trivialization

Distinguishing between types of atrocity is essential to any solvency.

Alain Destexhe. Belgian Politician and Author. 1995. Rwanda and genocide in the twentieth century Another reason why it is of fundamental importance to make distinctions between different kinds of catastrophes is that they are then revealed to vary greatly both in nature and in degree. However, the increasing amount of exaggerated news coverage given to any disaster, natural or manmade, nearly always infers that these events have one common denominator: they are seen as the product of fate and misfortune rather than the deliberate policy of any one individual or group. This results from the inability of the general public to make clear distinctions (value judgements) between a genocide and a civil war, a mugging and a road accident, famine, cholera epidemics and natural disasters Massacres and killings are put down to barbarism, age-old hatreds, ancient fears and tribal wars: ambiguous terms rooted in the racial thinking of the nineteenth century which often sowed the seeds of much later hostility. For example, the first real signs of antagonism between the Serbs and Croats only surfaced at the beginning of the twentieth century; and it was after 1960, in the countrysides of Burundi and Rwanda, where the populations mainly lived, that the social differences between Hum and Tutsi ceased to be seen as such and became an ethnic divide.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

19

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 20

Genocide Trivialization

Refusal to distinguish types of violence make tragedy certain.

Alain Destexhe. Belgian Politician and Author. 1995. Rwanda and genocide in the twentieth century It is totally unacceptable and even dangerous to group together all those who die in tragic circumstances, regardless of the way in which they die. It should be obvious that it is not at all the same thing to die from cholera in a refugee camp or as the targetted victim of ethnic cleansing in one's own home. If it were all one and the same, then there would be no more at stake than the right of all victims to our compassion. Crime and guilt then cease to be significant and the particularly horrible murder of one individual would be measured with the same stick as a mass killing.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

20

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 21

AT: Security

FIRST, STATES INEVITABLY COMPETE WITH EACH OTHER FOR INTERNATIONAL POWER ANY ATTEMPT TO DEVIATE FROM THIS STRUCTURE CAUSES VIOLENCE

Mearscheimer 2001 [John J., Prof. of Pol. Sci @ U. of Chicago, The Tragedy of Great Power Warfare] Great powers fear each other. They regard each other with suspicion, and they worry that war might be in the offing. They anticipate danger. There is little room for trust among states. For sure, the level of fear varies across time and space, but it cannot be reduced to a trivial level. From the perspective of any one great power, all other great powers are potential enemies. This point is illustrated by the reaction of the United Kingdom and

France to German reunification at the end of the Col War. Despite the fact that these three states had been close allies for almost forty-five years, both the United Kingdom and France immediately began worrying about the potential danger of a united Germany.

in a world where great powers have the capability to attack each other and might have the motive to do so any state bent on survival must be at least suspicious of other states and reluctant to trust them. Add to this the 911 problem the absence of

The basis for this fear is that a central authority to which a threatened state can turn for help and states have even greater incentive to fear each other. Morever, there is no mechanism, other than the possible self-interest of third parties, for punishing an aggressor. Because it is sometimes difficult to deter potential aggressors, states have ample reason not to trust other states and to be prepared for war with them.

The possible consequences of falling victim to aggression further amplify the importance of fear as a motivating force in world politics. Great powers do not compete with each other as if international marketplace. Political competition among states is a much more dangerous business than mere economic intercourse, the former can lead to war, and war often means mass killing on the battlefield as well as mass murder of civilians. In extreme cases, war can even lead to the destruction of states. The horrible consequences of war sometimes cause states to view each other not just as competitors, but as potentially deadly enemies. Political antagonism, in short, tends to be intense because the stakes are great. States in the international system also aim to guarantee their own survival. Because other states are potential threats, and because there is no higher authority to come to their rescue when they dial 911, states cannot depend on others for their own security. Each state tends to see itself as vulnerable and alone, and therefore it aims to provide for its own survival. In international politics, God helps those who help themselves. This emphasis on self-help

does not preclude states from forming alliances. But alliances are only temporary marriages of convenience: todays alliance partner might be tomorrows enemy, and todays enemy might be tomorrows alliance partner. For example, the United States fought with China and the Soviet Union against Germany and Japan in World War II, but soon thereafter flip-flopped enemies and partners and allied with West Germany and Japan against China and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

States operating in a self-help world almost always act according to their own self-interest and do not subordinate their interests to the interests of other states, or the so-called international community. The reason is simple: it pays to be selfish in a self-help world. This is true in the short term as well as in the long term, because if a state loses in the short run, it might not be around for the long haul. Apprehensive about the ultimate intentions of other states, and a ware that they oeprate in a self-help system, states quickly understand that the best way to ensure their survival is to be the most powerful state in the system. The stronger a state is relative to its potential rivals, the less likely it is that any of those rivals will attack it and threaten its survival. Weaker states will be reluctant to pick fights with more powerful states because the weaker states are likely to suffer military defeat. Indeed, the bigger the gap in power between any two states, the less likely it is that the weaker will attack the stronger. Neither Canada nor Mexico, for example, would countenance attacking the United States, which is far more powerful than its neighbors. The ideal situation is to be the hegemon in the system. As Immanuel Kant said, It is the desire of every state, or of its ruler, to arrive at a condition of perpetual peace by conquering the whole world, if that were possible. Survival would then be almost guaranteed

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

21

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 22

AT: Security

REALISM MUST BE USED STRATEGICALLY REJECTING IT RISKS WORSE USES

Stefano Guzzini, Assistant Professor at Central European Univ., Realism in International Relations and International Political Economy, 1998, p. 212 Therefore, in a third step, this chapter also claims that it is impossible just to heap realism onto the dustbin of history and start anew. This is a non-option. Although realism as a strictly causal theory has been a disappointment, various realist assumptions are well alive in the minds of many practitioners and observers of international affairs. Although it does not correspond to a theory which helps us to understand a real world with objective laws, it is a world-view which suggests thoughts about it, and which permeates our daily language for making sense of it. Realism has been a rich, albeit very contestable, reservoir of lessons of the past, of metaphors and historical analogies, which, in the hands of its most gifted representatives, have been proposed, at times imposed, and reproduced as guides to a common understanding of international affairs. Realism is alive in the collective memory and self-understanding of our (i.e. Western) foreign policy elite and public, whether educated or not. Hence, we cannot but deal with it. For this reason, forgetting realism is also questionable. Of course, academic observers should not bow to the whims of daily politics. But staying at distance, or being critical, does not mean that they should lose the capacity to understand the languages of those who make significant decisions, not only in government, but also in firms, NGOs, and other institutions. To the contrary, this understanding, as increasingly varied as it may be, is a prerequisite for their very profession. More particularly, it is a prerequisite for opposing the more irresponsible claims made in the name, although not always necessarily in the spirit, of realism.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

22

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 23

AT: Terror Talk

CRITICISM OF TERROR POWERLESSNESS RHETORIC RENATURALIZES ITS CAUSES, INSTILLING

Rodwell 2005 [Jonathan, PhD Cand. @ Manchester Metropolitan University, Trendy But Empty: A Response to Richard Jackson, 49th Parallel, Spring, www.49thparallel.bham.ac.uk/back/issue15/rodwell1.htm, 9-23-06//uwyo-ajl] The larger problem is that without clear causal links between materially identifiable events and factors any assessment within the argument actually becomes nonsensical. Mirroring the early inability to criticise, if we have no traditional causational discussion how can we know what is happening? For example, Jackson details how the rhetoric of antiterrorism and fear is obfuscating the real problems. It is proposed that the real world killers are not terrorism, but disease or illegal drugs or environmental issues. The problem is how do we know this? It seems we know this because there is evidence that illustrates as much Jackson himself quoting to Dr David King who argued global warming is a greater that than terrorism. The only problem of course is that discourse analysis has established (as argued by Jackson) that Kings argument would just be self-contained discourse designed to naturalise another arguments for his own reasons. Ultimately it would be no more valid than the argument that excessive consumption of Sugar Puffs is the real global threat. It is worth repeating that I dont personally believe global terrorism is the worlds primary threat, nor do I believe that Sugar Puffs are a global killer. But without the ability to identify real facts about the world we can simply say anything, or we can say nothing.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

23

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 24

AT: Cuomo

Preventing nuclear war is the absolute prerequisite to positive peace

Folk, Prof of Religious and Peace Studies at Bethany College, 78 (Jerry, Peace Educations Peace Studies : Towards an Integrated Approach, Peace & Change, Vol. V, No. 1, Spring, P. 58) Those proponents of the positive peace approach who reject out of hand the work of researchers and educators coming to the field from the perspective of negative peace too easily forget that the prevention of a nuclear confrontation of global dimensions is the prerequisite for all other peace research, education, and action. Unless such a confrontation can be avoided there will be no world left in which to build positive peace. Moreover, the blanket condemnation of all such negative peace oriented research, education or action as a reactionary attempt to support and reinforce the status quo is doctrinaire. Conflict theory and resolution, disarmament studies, studies of the international system and of international organizations, and integration studies are in themselves neutral. They do not intrinsically support either the status quo or revolutionary efforts to change or overthrow it. Rather they offer a body of knowledge which can be used for either purpose or for some purpose in between. It is much more logical for those who understand peace as positive peace to integrate this knowledge into their own framework and to utilize it in achieving their own purposes. A balanced peace studies program should therefore offer the student exposure to the questions and concerns which occupy those who view the field essentially from the point of view of negative peace.

Last printed 1/4/2013 10:17:00 PM

24

K the Dis Ad.

Dartmouth 2K9 25

AT: Kato

No Link: Kato criticizes not recognizing testing as an actual nuclear war, we just say we prevent an alternate nuclear war.

Kato, Political Science Professor at the University of Hawaii at Honolulu, 93 (Masahide, Nuclear Globalism: Traversing Rockets,

Satellites, and Nuclear War, Alternatives, V. 18, N. 3) Nuclear criticism finds the likelihood of "extinction" as the most fundamental aspect of nuclear catastrophe . The complex

problematics involved in nuclear catastrophe are thus reduced to the single possible instant of extinction. The task of nuclear critics is clearly designated by Schell as coming to grips with the one and only final instant "human extinction-whose likelihood we are chiefly interested in finding out about:" Deconstructionists, on the other hand, take a detour in their efforts to theologize extinction. Jacques Derrida, for example, solidified the prevailing mode of representation by constituting extinction as a fatal absence: Unlike the other wars, which have all been preceded by wars of more or less the same type in human memory (and gunpowder did not mark a radical break in this respect), nuclear war has no precedent. It has never occurred, itself; it is a non-event. The explosion of American bombs in 1945 ended a "classical," conventional war, it did not set off a nuclear war The terrifying reality of the nuclear conflict can only be the signified referent, never the real referent (present or past) of a discourse or text At least today apparently." By representing the possible extinction as the single most important problematic' of nuclear catastrophe (posing it as either a threat or a symbolic void),

nuclear' criticism disqualifies the entire history of nuclear violence, the "real" of nuclear catastrophe as a continuous and repetitive process. The "real" of nuclear war is designated by nuclear critics as a "rehearsal' (Derrik De Kerkhove) or "preparation" (Firth) for what they reserve as the authentic catastrophes' The history of nuclear violence offers, at best, a reality effect to the imagery of "extinction." Schell summarized the discursive position of nuclear critics very succinctly, by stating that nuclear catastrophe should not be

conceptualized "in the context of direct slaughter of hundreds of millions people by the local effects: "8 Thus the elimination of the history of nuclear violence by nuclear critics stems from the process of discursive "delocalization" of nuclear violence. Their primary focus is not local catastrophe, but delocalized, unlocatable, "global" catastrophe

Extinction of the species is the most horrible impact imaginable, putting rights first is putting a part of society before the whole.

Schell 1982 (Jonathan, Professor at Wesleyan University, The Fate of the Earth, pages 136-137 uw//wej)

Implicit in everything that I have said so far about the nuclear predicament there has been a perplexity that I would now like to take up explicitly, for it leads, I believe, into the very heart of our response-or, rather, our lack of response-to the predicament. I have pointed out that our species is the most important of all the things that, as inhabitants of a common world, we inherit from the past generations, but it does not go far enough to point out this superior importance, as though in making our decision about ex- tinction we were being asked to choose between, say, liberty, on the one hand, and the survival of the species, on the other. For the species not only overarches but contains all the benefits of life in the common world, and to speak of sacrificing the species for the sake of one of these benefits involves one in

the absurdity of wanting to de- stroy something in order to preserve one of its parts, as if one were to burn down a house in an attempt to redecorate the living room, or to kill someone to improve his character. ,but even to point out this absurdity fails to take