Professional Documents

Culture Documents

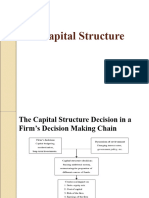

Dividend Policy and Capital Structure

Uploaded by

Masud IslamOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dividend Policy and Capital Structure

Uploaded by

Masud IslamCopyright:

Available Formats

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy The Two Modigliani&Miller Theorems

Hans Bystrm, July 2007

Some 50 years ago the two economists Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller (M&M) wrote two very important scientific articles. One was about a firms optimal capital structure (M&M I, 1958) and one was about a firms optimal dividend policy (M&M II, 1961). Modigliani & Miller proved that, in a theoretical world, neither the capital structure nor the dividend policy affected the value of the firm. That is, they showed that the choice of one particular capital structure or dividend policy over another is irrelevant for the shareholders of the firm. Basically, the management of the firm should focus on other more important problems such as where and in what the firms funds should be invested. This was a revolutionary finding at a time when a lot of effort was put into choosing optimal capital structures and dividend policies. Even though real-world frictions cause certain capital structures or dividend policies to be better than other, the differences are not as large as previously thought.

1 Optimal Capital Structure

In chapter 1 we will first define what a firms capital structure is and then explain why the choice of capital structure is irrelevant in a theoretical, so-called Modigliani & Miller, world. Finally, we will list some reasons why real-world phenomena still do make some capital structures better than other.

1.1 Different ways of raising finance (the capital structure)

In order to fund its activities a firm typically needs some kind of funding. In financial language, the firms chosen set of financing sources is called its capital structure. Now, there are several ways for a firm to raise finance (funding). One way of dividing the various sources of capital into different types is by labeling it as internal financing or external financing. Internal financing is a straightforward way for a firm to fund its business. Here, the firm simply uses its own saved profits from earlier years to fund expansions, takeovers, product development or whatever activity the firm needs to finance. If the firm chooses to turn to external financing, on the other hand, it has many more sources to choose from. Overall, external financing can be divided into equity- and

Dr Hans Bystrm Associate Professor of Finance Lund University

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

debt financing. Basically this means that a firm can issue equity or debt to raise the money it needs.1 If the firm chooses to issue equity (i.e., issue more stocks in its own name), then it distributes ownership in the firm to the financiers, and if it chooses to issue debt (i.e., issue corporate bonds in its own name) then it simply borrows money that has to be paid back to the financiers in the future (together with interest). It is important to understand the fundamental difference between debt- and equity-financing. While debt financing requires the borrower to make regular interest rate payments equity financing doesnt require the borrower to make repayments of any kind (as opposed to interest rate payments, dividends are not obligatory). Equity funding is therefore sometimes called permanent funding. While we will limit ourselves to the most classical source of equity funding in this paper, i.e. the issuance of ordinary stocks, we will separate between several classes of debt funding. A firm (or government for that matter) can issue debt (borrow money) in various ways. First, of course, it can turn to a bank for an ordinary bank loan. This is the traditional way for a firm to borrow money and although it is less common today than historically it is still very common. More and more, however, firms turn to the capital market for funding. The capital market is made up of all sorts of investors; individuals, other firms, banks, hedge funds, insurance companies etc. By turning to the capital market, the firm with borrowing needs does not have to turn to banks for funds. Instead, the capital market supplies the funds. In order to tap the capital market for funds, the firm issues bonds (so-called corporate bonds). These bonds require the firm to make regular interest rate payments in addition to pay back the borrowed money at maturity (which for instance could be in one years time, in five years or at whatever point in time agreed upon in the bond covenants/contract). As opposed to bank loans, bonds can be bought and sold by the investors in the capital market. This makes the borrower less dependent on having good relations with a borrowing bank. In addition to banks and the capital market, a firm can also borrow from its employees. An example of this is when a firm sets aside a certain share of the salary to a retirement fund administrated by the firm. Instead of getting the money up-front, the employee is promised a certain amount when retiring. Obviously, this is like a loan given by the employee to the firm. Money that belongs to the

For instance, if the electronics firm Samsung wants to use debt as a way of funding its activities it can issue Samsung bonds (which typically are tradable financial instruments just like Samsung stocks). If it instead wants to use equity as a mean of funding its business, it issues Samsung stock (and thereby dilutes the current stock capital).

Dr Hans Bystrm Associate Professor of Finance Lund University

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

employee is (temporarily) withheld by the firm. If the employee is young, the loan could have a very long maturity.2 Finally, leasing, although strictly not defined as borrowing, can at least be seen as an alternative to debt funding. If the firm decides to lease a piece of machinery, a tractor say, instead of buying it with borrowed money, the situation is very similar to if the firm had borrowed the money by a bank. In both cases, the firm has to make regular payments (leasing fees or interest rate payments). There is one important difference between leasing and borrowing, however. At maturity, if the firm had borrowed money to buy the tractor, then the firm would bear the market risk. That is, the risk that the tractors value has fallen more than expected. If the firm instead had leased the tractor there would be no risk involved. The firm would simply return the tractor to the leasing firm and thats that. In neither of the two cases does the firm have to make any initial outlays from its own funds however.

1.2 Optimal Capital Structure in an ideal (M&M) world

We have now learned how a firm can raise money to finance its ventures, i.e. we have learned how a firms capital structure might look like. A firm might choose to rely solely on equity financing, on a mixture of equity- and debt financing, or rely solely on different kinds of debt. If debt as well as equity is used, the firm has to decide on the relative weights of the two funding sources. Regardless of the firms exact choice, the balance of various finance forms is called the firms capital structure. Now, the question is whether some capital structure choices are better than other. For instance, should some firms rely on equity financing while other firms should limit themselves to issue equity? The answer, according to Modigliani & Miller, is that it does not matter. The capital structure choice is a non-issue since it is irrelevant! Modigliani & Miller (1958) says that the value of the firm, i.e. the stock price, is independent of the capital structure. As have been mentioned above, at the time of the publication this was a revolutionary finding. Of course, like most theoretical arguments, the results in the Modigliani & Miller (1958) paper are based on a set of simplifying assumptions. However, even after the assumptions have been relaxed, the main message of the Modigliani&Miller theorem (M&M I) remains; do not spend too much time on pondering about your capital structure! The aim of this short paper is not to fully list all the assumption, derivations and implications of the Modigliani & Miller (1958) paper. However, the most

2 It is important for the employee to consider the risk associated with lending money to the firm in this way. In addition to losing his or her job if the firm goes bankrupt, the employee might also lose any future retirement claims on the firm. Particularly employees who contemplate buying stocks in the firm where he or she works should think carefully about these kinds of commitments. It is not a good idea from a diversification perspective, which anyone who worked for the US firm Enron should know!

Dr Hans Bystrm Associate Professor of Finance Lund University

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

important assumptions need to be addressed; in the M&M world there are no taxes, no transaction costs and no information asymmetry. Despite appearing as quite strong, these assumptions are actually pretty common in the theoretical finance literature. Furthermore, in the next chapter we will see what happens when some of them are relaxed. Now, the Modigliani & Miller theorem says that in a Modigliani & Miller world the total market value of all the assets issued by a firm is determined by the risk and return of the firms real assets, not by the mix of issued securities (the capital structure). This seems quite obvious, when you think about it, and it would actually be more surprising if the mix had an effect on the value of the stocks and bonds issued by the firm. After all, the value of a firm must depend on the business of the firm, whether it is good or bad, and not on how the funding is secured. Shouldnt it? The answer is yes, as M&M tells us, but the real feat of Modigliani & Miller is that they managed to describe, theoretically, why it is so. We are in no way to prove the Modigliani & Miller theorem (M&M I) here but learning about the main idea behind the derivation might simplify the digestion of the theorem. Basically, the idea behind the theorem is that the investor, i.e. the stockholder, can simulate any capital structure on her own and the firm therefore has no reason to dwell on this. If the investor is highly indebted, herself, the risk and return of the firms stock (to the investor) will simply be the same as if the firm, itself, was highly leveraged (indebted). This finding, together with the observation that a more leveraged firm (a firm with relatively more debt) not only returns a higher expected return to the investor, but also a higher risk is the center piece of the Modigliani & Miller theorem. We will do with that for now and instead we are going to see what happens if some of the assumptions of the original theorem are relaxed. That is, what about the real world where frictions like taxes and information asymmetry exist? Will the capital structure play a larger role there?

1.3 Optimal Capital Structure in the real world

If the capital structure doesnt affect the value of the firm, how come firms choose certain capital structures ahead of other? The reason is, of course, that the M&M results are outputs from a theory and that in reality there might be some drawbacks/costs associated with certain capital structures. Basically, certain reallife frictions create value out of an optimal choice of capital structure. One reason for firms too limit the amount of debt it raises is that higher indebtedness automatically leads to a situation where it is more likely that the firm will go bankrupt in the future (which occurs if the value of the firms debt is larger

Dr Hans Bystrm Associate Professor of Finance Lund University

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

than the value of the firms assets). Why is that? Basically, more debt means more interest rate payments (that have to be made in order to avoid bankruptcy) which in turn means more pressure to make regular profits (one year without profits can cause bankruptcy if no reserve funds are available). In contrast, if a firm is fully funded with equity, then, in theory, it cannot default on its debt (since there is none). This fact is known by market participants, consumers, employees etc. and it means that a firm who loads up on debt is considered, by all informed observers, to become more likely (albeit probably still quite unlikely) to go bankrupt at some point in the future. This, in turn, can be costly to the firm. Even if the firm actually doesnt go bankrupt, the actions by consumers etc. might be very unfortunate to the firm. In the end, these actions might even drive the firm into bankruptcy! Imagine a highly indebted car company (GM) that suddenly borrows a large amount of additional money. Why is that a costly alternative for GM? Why might this be a sub-optimal choice of capital structure? First, as a consumer you might be worried about a future bankruptcy and the consequences that might have for future service, availability of spare parts etc. on your GM car. As a result you buy another car, which of course lowers the profit (and stock price) of GM. Second, any suppliers of car parts to GM might also be wary of the new loans taken by GM. They might start worrying about a pending GM bankruptcy and start looking for new buyers of their car parts. As a result, GM might loose some of its bargain power towards the supplier and this will hurt its profits and stock price. Employees at GM might also get worried and look for jobs elsewhere. The best employees are probably the first to leave and this would hurt GM and its stock price. To sum up, the value of GM is obviously not immune to the chosen capital structure and in this case the resulting capital structure was simply skewed towards too much debt to be healthy for the firm. Too little debt might also be sub-optimal for a firm. A well known phenomena is managers in a firm that squander the firms money on things that might be optimal for the manager but less so for the firm. As an example, a high-flying CEO of a firm might decide to buy a helicopter for personal use (in order to avoid traffic jams on his way to work). Now, while expenses like these might be reasonable in some cases (if you live in Mumbai lets say) they might simply be more of a nice present to the CEO in other cases (if you live in Sweden or any other country with modest traffic). Now, the more debt a firm has issued the more discipline is exercised at the CEO. With a lot of debt follows a lot of interest rate payments that have to be made (at regular intervals) and this motivates the CEO to ration the firms money better. In the case of bankruptcy, the CEO often looses both his job and severance payments. Therefore, by issuing more debt the firm can actually increase its value somewhat. To sum up, the value of the firm is, again, dependent

Dr Hans Bystrm Associate Professor of Finance Lund University

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

on the chosen capital structure, and in this case the resulting capital structure was simply skewed towards too little debt to be healthy for the firm. Finally, another reason for a firm to issue more debt is taxes. In some countries interest rate payments are deducted from the firms profits before taxes are paid. This is obviously better than if the interest rate expenses were deducted after taxation, as dividends typically are. This difference between dividends (payments to equity providers) and interest rate payments (payments to debt providers) encourages firms to turn to debt instead of equity. Again, the chosen capital structure is not irrelevant and in this case the resulting capital structure should be tilted towards more debt due to tax reductions associated with debt financing. Now, even if the examples listed above tell us that both too low and too high levels of debt may be problematic for a firm, it should be stressed that Modigliani & Miller still have a valid point. While their conclusion that the capital structure is completely irrelevant perhaps is a bit too strong in real world situations, the basic idea behind the argument is convincing. Furthermore, while managers 50 years ago thought that the difference between the right capital structure and the wrong ones were dramatic (in terms of value lost to the stockholders) todays managers know of M&M I and realize that the gains from choosing an optimal capital structure, albeit existent, are fairly modest.

2 Optimal Dividend Policy

In chapter 2 we will first describe what is meant by a firms dividend policy and then explain why the choice of dividend policy is irrelevant in a theoretical Modigliani & Miller world. Finally, we will mention some reasons why real-world phenomena do make some dividend policy choices better than other. The discussion in this chapter is very similar to that in the previous chapter, but here it deals with a firms dividend choices instead of with its funding choices.

2.1 Different ways of distributing cash to shareholders (the dividend policy)

A firms dividend policy has nothing with ordinary policy (or politics) to do. Instead, it is just a fancy word used to describe how large dividends a firm is paying and how the firm chooses to arrange the actual dividend payment. All dividend payments are payments from the firm to the shareholder. Furthermore, firms do not have to pay any dividends, but if they decide to do so they have all the rights to choose the size of the dividend. In addition, instead of an ordinary cash dividend a firm can also choose to buy back shares. The result is almost the same as a dividend payment and in both cases cash is channeled from the firm to the shareholder at the same time as the shareholders (financial) exposure to the firm

Dr Hans Bystrm Associate Professor of Finance Lund University

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

declines. In a stock repurchase, however, only those shareholders who actually decide to sell shares are involved, while in a dividend payout all shareholders are forced to accept the dividends paid to them. Now, our intention is not to fully describe all the various ways that dividend can be arranged but rather to stress that this choice is labeled as the firms dividend policy.

2.2 Optimal dividend policy in an ideal (M&M) world

In chapter 1 we saw that in an ideal, so-called M&M world, a firms capital structure was irrelevant for the shareholder since the shareholder could emulate the capital structure of the firm on their own. Exactly the same reasoning is found in this chapter, but for the firms dividend policy. Here, a second Modigliani & Miller (1961) theorem, called M&M II, says that in a Modigliani & Miller world the total market value of all the assets issued by a firm is independent of the way cash is distributed to the shareholders (the dividend policy). Like in the earlier case of the capital structure, we are not attempting to prove the second Modigliani & Miller theorem (M&M II) here but, again, the general thinking behind the proof is worth presenting. Similar to the capital structure irrelevance in chapter 1, the idea behind the second M&M theorem is that the investor, i.e. the stockholder, can simulate any dividend policy on his own and the firm should therefore focus on other issues. In this case it is even easier to understand the basic idea. Basically, if the investor finds the dividend to be too low, he can simply sell some of his stocks and in that way reduce his holdings in the firm at the same time as he receives more cash. The reason for the outcome of this to be exactly the same as if the firm had paid a higher dividend is that the firms stock price typically falls with the same amount as the dividend at the day of the dividend payment. If the situation is reversed, i.e. the investor thinks the dividend is too large, then he can simply reinvest some or all of it in new stocks in the same firm. In that way the investors exposure to the firm is not lowered (or is just partly lowered) as a result of the dividend payment at the same time as his cash holdings remain the same (or are only slightly higher) as/than before the dividend. This is the situation in a theoretical M&M world and in the next chapter we will see what happens if some of the assumptions of the M&M II theorem are relaxed. If real-world-frictions like taxes and information asymmetry are introduced, will the dividend policy be irrelevant then as well?

2.3 Optimal dividend policy in the real world

If the dividend policy has no effect on the value of the firm (the stock price), why do firms think twice before they decide on a certain size of their dividends (and on

Dr Hans Bystrm Associate Professor of Finance Lund University

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

whether they should buy back shares instead of paying cash dividends)? The reason is, of course, that similarly to how certain capital structures are better than other, in the face of real-life-frictions such as taxes shareholder value can created from choosing an optimal dividend policy. First of all, if dividends and stock repurchases are taxed differently, then, of course, the firm chooses the mean of cash payout that leads to the most advantageous (highest) tax deduction. One example of how taxation may differ between the two dividend policies, is that stock sales profits can be netted with stock sale losses (and thereby affect the net tax) in a way that dividend income cannot. As a result, stock repurchases have become so popular (in the US at least) that regular stock repurchases in lieu of ordinary dividends are prohibited by law. In sum, taxation skews the results in the M&M theorem towards favouring some dividend policies before other. A reason for firms to avoid too large dividend payments is when they are about to expand, buy other companies or in other ways consider spending large sums of cash in the near future. Why is that? In a perfect capital market they could just tap the market when/if they need cash! Now, in the real world there are imperfections such as information asymmetries, and this creates value in reducing the dividend payment for an expanding firm. The reason is, of course, that in order to raise cash in the future the firm will have to convince the capital market that it is creditworthy. Since the market knows less than the firm about the firm (of course) the market will require a risk premium to lend to it. This is an unnecessary cost for the firm (who knows it is creditworthy) and it better reduces the dividend payment and uses the cash for its expansion plans. Why cross the river for water?! The same holds for fund raising organized by investment banks. The investment bank typically charge a significant amount to help the firm raise cash and these fees can be avoided by skipping the dividend payment. In sum, external financing costs cause firms to keep dividends at a lower level than without these costs (as in the M&M world). Finally, a third reason why firms choose a particular dividend policy is the signalling effect of the dividend. For some reason, the size of the dividend seems to be of relevance to many investors. A reduction of the dividend size is taken as bad news. Similarly, a hike in the size of the dividend is interpreted by the investors as good news. Basically, if the firm is doing well it can afford to pay large dividends and if it is having financial problems it probably has to reduce the dividend. At least thats how the reasoning goes. Even if there is a gain of truth in these statements it is not the whole story. As we have seen before, the firm is free to choose its dividend policy for other reasons than the size of the firms profits and it is highly possible that the firm, for example, decided to keep the dividend low for the simple reason that is has plenty of investment opportunities that it need to fund

Dr Hans Bystrm Associate Professor of Finance Lund University

Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

in the near future. This is not exactly bad news! Despite this, however, investors seem to value stability in the dividend policy and firms usually try to keep the divided fairly close to that of previous years in order to avoid too much speculation from the investors side. To sum up, signaling is an important factor to consider when targeting the dividend size and this means that the dividend policy is relevant, not irrelevant. The examples listed above tell us that the dividend policy in the real world actually might play a role for the firms owners. It should be stressed, however, that the Modigliani & Miller theorem (M&M II) is valid up to a certain point. In the same way as how managers 50 years ago thought that the difference between the right and wrong capital structure was dramatic (M&M I) they also believed that choosing an optimal dividend policy was an important area for the management. Todays managers, however, know of M&M II and realize that the gains from choosing an optimal dividend policy are fairly modest.

References

Modigliani, F. and Miller M. H. (1958). The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment.American Economic Review 48(3), 261297. Miller, M. H. and Modigliani, F. (1961). Dividend Policy, Growth and the Valuation of Shares. Journal of Business, 34, 411-33.

Dr Hans Bystrm Associate Professor of Finance Lund University

You might also like

- Securitization and Structured Finance Post Credit Crunch: A Best Practice Deal Lifecycle GuideFrom EverandSecuritization and Structured Finance Post Credit Crunch: A Best Practice Deal Lifecycle GuideNo ratings yet

- Brief Write-Up On Pass Through Certificates (PTCS) : BackgroundDocument4 pagesBrief Write-Up On Pass Through Certificates (PTCS) : Backgroundits_different17No ratings yet

- Tax Equity Financing: An Introduction and Policy ConsiderationsDocument18 pagesTax Equity Financing: An Introduction and Policy ConsiderationsCAMILA GARZON GONZALEZNo ratings yet

- Dental Office DesignDocument231 pagesDental Office Designturkeyegypt100% (2)

- Guide To Par Syndicated LoansDocument10 pagesGuide To Par Syndicated LoansBagus Deddy AndriNo ratings yet

- How to structure investments to protect downsideDocument6 pagesHow to structure investments to protect downsidehelloNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Law On CooperativesDocument4 pagesIntroduction To Law On CooperativesSembrana CampuedNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure and Dividend PolicyDocument25 pagesCapital Structure and Dividend PolicySarah Mae SudayanNo ratings yet

- Bank Management CHAP - 01 - 6edDocument51 pagesBank Management CHAP - 01 - 6edNikhil ChitaliaNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure: Capital Structure Refers To The Amount of Debt And/or Equity Employed by ADocument12 pagesCapital Structure: Capital Structure Refers To The Amount of Debt And/or Equity Employed by AKath LeynesNo ratings yet

- Leveraged Buyout (LBO) Private EquityDocument4 pagesLeveraged Buyout (LBO) Private EquityAmit Kumar RathNo ratings yet

- Cash and Liquidity ManagementDocument14 pagesCash and Liquidity ManagementAldrin ZolinaNo ratings yet

- Business Intelligence in BankingDocument299 pagesBusiness Intelligence in Bankingsohado100% (1)

- Capital Structure TheoriesDocument25 pagesCapital Structure TheoriesLalit ShahNo ratings yet

- Fund Flow Analysis at Nerolac PaintsDocument11 pagesFund Flow Analysis at Nerolac PaintsBala SudhakarNo ratings yet

- A Guide To The Initial Public Offering ProcessDocument12 pagesA Guide To The Initial Public Offering Processaparjain3No ratings yet

- Debentures and Loan Capital ExplainedDocument26 pagesDebentures and Loan Capital ExplainedhaninadiaNo ratings yet

- FM09-CH 27Document6 pagesFM09-CH 27Kritika SwaminathanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Risks of Financial Inter MediationDocument69 pagesChapter 7 - Risks of Financial Inter MediationVu Duy AnhNo ratings yet

- Asset Allocation: Balancing Financial Risk, Fifth Edition: Balancing Financial Risk, Fifth EditionFrom EverandAsset Allocation: Balancing Financial Risk, Fifth Edition: Balancing Financial Risk, Fifth EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Capital StructureDocument4 pagesCapital StructurenaveenngowdaNo ratings yet

- Securitization of BanksDocument31 pagesSecuritization of BanksKumar Deepak100% (1)

- GenMath11 Q2 Mod1 Simple-And-Compound-Interest Ce1ce2Document30 pagesGenMath11 Q2 Mod1 Simple-And-Compound-Interest Ce1ce2Joan BalmesNo ratings yet

- Debt management ratios analysisDocument4 pagesDebt management ratios analysisJohn MuemaNo ratings yet

- Hedge Funds Overview: Characteristics, Fees, Leverage & GrowthDocument31 pagesHedge Funds Overview: Characteristics, Fees, Leverage & GrowthprachiNo ratings yet

- Asset Backed SecuritiesDocument179 pagesAsset Backed SecuritiesShivani NidhiNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Capital StructureDocument38 pagesDeterminants of Capital StructureAbdul QadoosNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisitions Notes at Mba Bec Doms of FinanceDocument15 pagesMergers and Acquisitions Notes at Mba Bec Doms of FinanceBabasab Patil (Karrisatte)100% (1)

- IAS 7 - Statement of Cash FlowsDocument2 pagesIAS 7 - Statement of Cash FlowsMarc Eric RedondoNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Capital Structure in Ethiopian Commercial BanksDocument92 pagesDeterminants of Capital Structure in Ethiopian Commercial Banksyebegashet100% (1)

- Agency Theory Suggests That The Firm Can Be Viewed As A Nexus of ContractsDocument5 pagesAgency Theory Suggests That The Firm Can Be Viewed As A Nexus of ContractsMilan RathodNo ratings yet

- PWC Mutual Fund Regulatory Services Brochure PDFDocument31 pagesPWC Mutual Fund Regulatory Services Brochure PDFramaraajunNo ratings yet

- Hedge Funds and Private Equity - A Critical AnalysisDocument21 pagesHedge Funds and Private Equity - A Critical AnalysisGeorge SatlasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Dividend Policy and Retained EarningsDocument5 pagesChapter 8 Dividend Policy and Retained EarningsYut YE50% (2)

- FINS5513 Security Valuation and Portfolio Selection Sample ExamDocument8 pagesFINS5513 Security Valuation and Portfolio Selection Sample Examoniiizuka100% (1)

- EBIT-EPS analysis for financing plan decisionsDocument6 pagesEBIT-EPS analysis for financing plan decisionsSthephany GranadosNo ratings yet

- Trust ModarabaDocument56 pagesTrust ModarabaZubair MirzaNo ratings yet

- BaringsDocument24 pagesBaringsmnar2056481100% (1)

- Cash and Liquidity Management - Topic 3Document47 pagesCash and Liquidity Management - Topic 3kodeNo ratings yet

- Curacao FoundationsDocument32 pagesCuracao Foundationsreuvek6957No ratings yet

- Introduction To Investment BankingDocument45 pagesIntroduction To Investment BankingNgọc Phan Thị BíchNo ratings yet

- A Corporate BondDocument2 pagesA Corporate BondMuhammad KhurramNo ratings yet

- Treasury ManagementDocument10 pagesTreasury Managementrakeshrakesh1No ratings yet

- Hw1 Andres-Corporate FinanceDocument8 pagesHw1 Andres-Corporate FinanceGordon Leung100% (2)

- Week 7 Workshop Solutions - Long-Term Debt MarketsDocument3 pagesWeek 7 Workshop Solutions - Long-Term Debt MarketsMengdi ZhangNo ratings yet

- Dividend PolicyDocument44 pagesDividend PolicyShahNawazNo ratings yet

- MNC TNCDocument1 pageMNC TNCshakiraNo ratings yet

- Understanding the concept and features of securitizationDocument39 pagesUnderstanding the concept and features of securitizationSakshi GuravNo ratings yet

- FM S5 Capitalstructure TheoriesDocument36 pagesFM S5 Capitalstructure TheoriesSunny RajoraNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know About Mutual FundsDocument7 pagesEverything You Need to Know About Mutual FundsNeha GoyalNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisitions ExplainedDocument11 pagesMergers and Acquisitions Explainedvishnubharat0% (1)

- SEBI Role and FunctionsDocument28 pagesSEBI Role and FunctionsAnurag Singh100% (4)

- WbsDocument32 pagesWbsdeven_cNo ratings yet

- Foreign Exchange Risk ManagementDocument12 pagesForeign Exchange Risk ManagementDinesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Treasury Bills: Working Capital Management Assignment - 1Document4 pagesTreasury Bills: Working Capital Management Assignment - 1Divya Gopakumar100% (1)

- Hostile TakeoverDocument15 pagesHostile TakeoverKiran MankodiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 Agency Theory SolutionDocument7 pagesChapter 14 Agency Theory SolutionariestbtNo ratings yet

- Chap 006Document51 pagesChap 006kel458100% (1)

- Capital MarketDocument15 pagesCapital Marketरजनीश कुमारNo ratings yet

- The Industrial Organization and Regulation of the Securities IndustryFrom EverandThe Industrial Organization and Regulation of the Securities IndustryNo ratings yet

- Treasury Operations In Turkey and Contemporary Sovereign Treasury ManagementFrom EverandTreasury Operations In Turkey and Contemporary Sovereign Treasury ManagementNo ratings yet

- BFI 305 Financing Small Business QPDocument11 pagesBFI 305 Financing Small Business QPministarz1No ratings yet

- Philippine Planning Journal Article Reviews Government Role in Housing SectorDocument70 pagesPhilippine Planning Journal Article Reviews Government Role in Housing SectorJica DiazNo ratings yet

- Indus Bank - Report On Summer TrainingDocument34 pagesIndus Bank - Report On Summer TrainingZahid Bhat100% (1)

- Equitable MortgageDocument10 pagesEquitable Mortgagejohnlee rumusudNo ratings yet

- Hsslive-Chapter 5 BRS 1 PDFDocument2 pagesHsslive-Chapter 5 BRS 1 PDFRam IyerNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship NotesDocument12 pagesEntrepreneurship NotesSyed Adeel ZaidiNo ratings yet

- Merchant Bank in IndiaDocument14 pagesMerchant Bank in IndiaRk BainsNo ratings yet

- Lehman Brothers and LIBOR ScandalDocument16 pagesLehman Brothers and LIBOR Scandalkartikaybansal8825No ratings yet

- J.P. Morgan - Taking EM Asia's Pulse PDFDocument7 pagesJ.P. Morgan - Taking EM Asia's Pulse PDFkumarrajdeepbsrNo ratings yet

- Bank Mandiri: Growing A High Yield Loan BookDocument7 pagesBank Mandiri: Growing A High Yield Loan Bookagustus.septNo ratings yet

- Hands On BankingDocument134 pagesHands On BankingTaufiquer RahmanNo ratings yet

- Eton Properties Philippines, IncDocument10 pagesEton Properties Philippines, IncraefsNo ratings yet

- Reasearch PaperDocument21 pagesReasearch PaperTweenie DalumpinesNo ratings yet

- SMEs in Pakistan (Presentation by AZ) 040213Document90 pagesSMEs in Pakistan (Presentation by AZ) 040213zahoor.asad7753No ratings yet

- Karur Vysya Bank Is A Scheduled Commercial BankDocument4 pagesKarur Vysya Bank Is A Scheduled Commercial BankMamtha KumarNo ratings yet

- What Is A MortgageDocument6 pagesWhat Is A MortgagekrishnaNo ratings yet

- Bond Market - MMSDocument124 pagesBond Market - MMSkanhaiya_sarda5549No ratings yet

- GBL Reporting NotesDocument6 pagesGBL Reporting NotesKarla Marie TumulakNo ratings yet

- Winding Up - 2017Document44 pagesWinding Up - 2017Lim Yew TongNo ratings yet

- CA IPCCAuditing & Assurance372722Document11 pagesCA IPCCAuditing & Assurance372722piyushNo ratings yet

- Soneri BankDocument28 pagesSoneri Bankfahadali966No ratings yet

- Balance Sheet of Ambuja CementDocument4 pagesBalance Sheet of Ambuja CementMansharamani ChintanNo ratings yet

- Complaint AffidavitDocument4 pagesComplaint AffidavitDever GeronaNo ratings yet

- Intracompany Accounting SetupDocument9 pagesIntracompany Accounting SetupcanjiatpNo ratings yet

- FMCG Profit AnalysisDocument8 pagesFMCG Profit AnalysisTarun BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Installment Sales & Long-Term ConsDocument6 pagesInstallment Sales & Long-Term ConsSirr JeyNo ratings yet

- Court Rules Heirs Have No Share in Lumber CompanyDocument14 pagesCourt Rules Heirs Have No Share in Lumber CompanyKrister VallenteNo ratings yet