Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Women S Rights

Uploaded by

Ghanashyam DevanandOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Women S Rights

Uploaded by

Ghanashyam DevanandCopyright:

Available Formats

Reading 13. (A) Ch. 1: Women and Gender: Aspects of Inequality in Tribal Society.

(Virginius Xaxa) Ethnographic accounts of tribes have been the hallmark of tribal studies in India until the country attained Independence. It is mainly from such accounts that we can get an idea of the position of women in tribal societies (restrictions, taboos, rights, privileges, freedom etc.). Tribal Women in Traditional Setting: Indian Anthropological Society, 1987- Region wise survey of tribal women- points out that that the subject of tribal women have been either ignored or merely briefly dealt with; with the exception on Verrier Elwin and Furer Haimendorf. But even in such works, the assignment of status of women has been far from uniform. Eg. The Naga (mostly Nagaland) and the Baiga (Jharkhand) tribal women as described by Elwin. And Furer who talks about how women in most civilized parts of India may well envy the women of the Naga Hills. Hutton attributes a higher social status to Sema Naga women on the grounds that marriage among the tribe is based on choice and a girl is never married against her will. Now the discrepancy in the exact description of the status of women mainly arises because of the way the term status has been conceived by various scholars. 2 views: (i) Status of women as linked with womens role in the social system. (ii) Status of women in the sense of prestige and pride, i.e. in terms of womens legal status and opportunities. However, in tribal studies, such a distinction of the terms usage has been overlooked and almost used interchangeably. Also another important issue here is that such tribal societies have been mostly studied in relation to the other. This is problematic. Hardly any attempt has been made to study tribes in terms of the values prevailing in those tribal societies. Women in a Changing Tribal Society: A distinction has been maintained between a tribe and civilization, but the two have not been understood in isolation. The understanding that they are in interaction with the other has subsequently led to the dominant perspective that a tribal society is not static but undergoing a process of change. Thereby, changes occurring in tribal society have been conceived in terms such as the tribe moving in the direction of becoming a part of civilization and being assimilated into the society that such a civilization represents. Bose: Tribes being absorbed into the Hindu society such that they are being converted into castes. Also, the movement towards Christianity; both have been considered as significant processes of cultural change. Roy Burman: Sanskritization process among tribes, hence opting for early marriage and discouraging widow remarriage and divorce. Mann also says the same with the example of Bhil women. While the change moved in a somewhat different direction w.r.t the conversion to Christianity. Equal religious worship participation, access to modern education for women. However, it also introduced a variety of restrictions on the name of church ethics and law that militated against the freedom that tribal women had enjoyed earlier (Such as segregation of boys and girls, no divorce etc. Note: In Hinduization, such

restrictions were part of the concern with maintaining respectability and status. While in Christianization, the concern was of religious morals and values. Assumptions Underlying the Study of Tribes: Basic assumption: Tribes are primitive, savage and backward. This point is made repeatedly in accounts of their means of livelihood and survival, technology, food habits, lifestyle, and more importantly through representations of their bodies. A dominant view of tribes and tribal societies led to treating them almost socially and culturally like animals. Study indicating that almost 95% upper caste women considered the Bhil tribal women to be socially inferior Mann. This sort of view was also internalized to some degree by the members of the tribes themselves, as their inherent values were contrary to the dominant values of the larger society. Mandelbaum suggested this couldve arisen due to the tribal peoples inclination towards direct, unalloyed satisfaction in pleasure of the senses- food, alcoholic drink, sex or dance. Ethnographers, British as well as Indian, were on the whole rooted in the spirit of Enlightenment rationality (Freedom, equality, fraternity basic values of assessment). Therefore, they judged the position of women in tribal society in the context of the dominant values of the west which were contrary to the dominant values of the larger Indian society. In recent years, tribal women portrayed to have a better status than those held by women of caste-based societies, mostly based on sex-ratio and female work-force participation. Note: Topics such as economic burden and workload borne by tribal women, access to education, foodnutrition, modern occupations, and political participation have mostly not been considered. Stages of Social Formation: Position of tribal women in context of all around socio-economic changes in tribal society has been another area of focus in the study. One of the dominant ways of looking at change though this is to study changes in the means of livelihood and survival. This can be seen through the transition from food gathering to food production or from slash and burn/ swidden to settled agriculture. This has led to the event wherein the belief of prevailing inequality in traditional tribal society was thereby under scrutiny. Gender equality has been highlighted as the most pervasive, of these. The relative position of women and men under different types of social formation (such as food gathering, swidden agriculture, settled agriculture and state formation) has been studied here. Also another way has been through studying of different tribal societies without using their social formations as the reference point but w.r.t division of labour, forms of property, religious institutions, family organization and the state. Nathan uses the example of Khasis (Meghalaya): The higher social status of women due to their rights of ownership is subsequently neutralized by the mens control over the decision making process. Also, the problem of witch-hunting (Kelkar and Nathan) mightve been associated in certain ways with the attempt of obtaining the property rights by the male agnates of the deceased. But as per Xaxa, such a generalization cannot be made. Examples of customary laws, such as Bride price amongst certain tribes of Arunachal Pradesh (Nongbri discusses this), wherein according to Nongbri women are treated as mere commodities, have been discussed to highlight the inherent gender inequality in such societies. Unnithan Kumar discusses the practice of bride price in certain other societies such as the Taivar tribe of Rajasthan. Finally, Xaxa comments: (i) Division of labour in tribal society is based

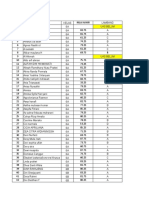

on sex, is an accepted fact. However, the notion of studying tribal women from the perspective of their inherent values is difficult. Therefore, rather than talking about high and low status, it is more pertinent to talk about gender inequality. (ii) Nathan: Ploughing land for women in tribal society was seen as a taboo and couldve been due to the denial of women control over the means of production, eg. Oraon and Ho women. Xaxa feels that such an understanding is not adequate as the Brahmans were also forbidden from ploughing as per the customary laws. Social Differentiation: Social differentiation is mainly rooted in forces outside of tribal societies, such as introduction of private property, growth of trade, emergence of the market, emigration of non-tribes in search of land & employment, modern education, opening up of new occupations, state-sponsored programmes etc. Many lost their land and were compelled to take up employments as labourers. Also, a minority were able to take advantage of the forces unleashed by the market and the benefits extended by the state to the tribes. This has led to differentiation among the tribe based on criteria such as education, occupation, income, wealth and assets. This has led to emergence of class relations originally absent in traditional tribal societies. The women of the well off sections enjoy certain advantages: primary education, higher education away from native land, migration to cities etc. While in contrast, women from the lower stratum have low school enrolment, higher dropout rates, and hence they hardly move beyond the primary level and thereby constrained to work as labourers. Tribal Movements: One of the general concerns in the study of tribal movements in India has been to provide a system of classification. Such study has been absent mainly due to the assumption that there is no class differentiation in tribal society. Forest-agrarian movement: greater bearing on the lives of tribal women, yet accounts of their dominating role in such movements are absent. However, there have been accounts wherein women participated in other tribal movements. The Tebhaga movement (1946-7), Agrarian-forest movement by Jharkhand Mukti Morcha & Marxist Coordination Committee, and also the Santhal rebellion (1855) are examples of the same. Rani Gaidinliu and Raj Mohini Devi: Tribal Women leaders who led the anticolonial struggle amongst the Nagas. Economic and Political Development: Post-independence, various provisions were made by the state for the protection and upliftment of tribes. However, the benefits under these provisions have been distributed very unevenly across the tribes. Within the tribes too, distribution is very uneven along the line of sex. Refer to table 10.1. (The data clearly points out that there is a bias against women in the values of tribal societies, especially in the domain of politics social and economic life. Women are now exposed to greater hardships due to depletion of resources level of household and the community but also to the greater danger due to the changing nature of work and livelihood, such as collecting fuel wood, water etc. This also leads to large scale migration of tribal men and women due to the lack of alternative modes of livelihood.

Emerging Discourse: Tribal communities in India are both diverse and heterogeneous with regard to language, physical characteristics, demographic traits, means of livelihood and cultural exposure. Therefore, it is difficult to generalize about the position of women as whole amongst all thee varying tribal societies and thereby what can be observed will at best be merely being illustrative and heuristic. Despite such heterogeneity, tribes share one trait in common, that they are different from the dominant community of the region who are often perceived as aliens or outsiders. This is mostly seen in cases wherein the recognized tribal groups are engaged in intense competition and conflict with those from outside such tribal community. Jharkhand: Outsiders here can be invariably described as oppressors and exploiters and are addressed by the term diku. Meghalaya: The term used for outsiders here in dakhar, it is a very strong term but carries lesser degree of exploitative connotations. In a social arrangement such as this, tribal societies have been experiencing a serious threat to the identity on account of the kind of changes taking places - steady erosion of life support systems land & forest, increasing pauperization, sense of loss of language, minority in their own land. One of the most important points to note here is the large scale alienation of tribal land from tribes to non-tribes. One way by which non-tribals acquire tribal land is by marrying a tribal woman. Tribal women entering such marriages are not only seen as aligning with the dikus but also as conduits of such form of land transfer, which is an emotive issue. Hence the opposition against tribal women marrying nontribal men is compounded by the weight of tribal tradition, according to which marriage outside the community is regarded a crime as serious as incest.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Digital Booklet - LegendDocument29 pagesDigital Booklet - Legendprueba1092100% (3)

- Simon Gray, English Playwright and MemoiristDocument3 pagesSimon Gray, English Playwright and MemoiristIlinca NataliaNo ratings yet

- The Kabballah Tree ExposedDocument2 pagesThe Kabballah Tree ExposedScrivener666No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Macbeth StroyboardDocument4 pagesMacbeth StroyboardfieryjackeenNo ratings yet

- Case List Criminal Law.Document13 pagesCase List Criminal Law.Ghanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- Romeo and Juliet Sample ScriptDocument15 pagesRomeo and Juliet Sample Scriptwamu885100% (2)

- Suzuki Guitar Vol. 2 - Waltz (Calatayud)Document2 pagesSuzuki Guitar Vol. 2 - Waltz (Calatayud)Beniamino Trucco100% (1)

- Marie LaveauDocument4 pagesMarie LaveauRuby GearingNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 South AmericaDocument18 pagesChapter 6 South Americapamela alviolaNo ratings yet

- Gandhi Medical College AlumniDocument231 pagesGandhi Medical College AlumniAbhishek SinghNo ratings yet

- The Meet Shall Be Conducted According To The Rules of Amateur Athletic Federation of IndiaDocument2 pagesThe Meet Shall Be Conducted According To The Rules of Amateur Athletic Federation of IndiaGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- It Is A Matter of General Practice That The Sports Committee Convenor Carries Around A Bag With HimDocument2 pagesIt Is A Matter of General Practice That The Sports Committee Convenor Carries Around A Bag With HimGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- Fuller - Positivism and Fidelity To Law - A Reply To Professor HartDocument44 pagesFuller - Positivism and Fidelity To Law - A Reply To Professor HartGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- Class Rounds Year 3 Oral Rouns Tab SheetDocument2 pagesClass Rounds Year 3 Oral Rouns Tab SheetGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- Project DeeksharaoDocument26 pagesProject DeeksharaoGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- Case List - Mid TermDocument9 pagesCase List - Mid TermGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- Veiled in The FinalDocument18 pagesVeiled in The FinalGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument21 pagesHistoryGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- History Summaries IIDocument12 pagesHistory Summaries IIGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- It Is Amazing How Quickly The Kids Learn To Drive A CarDocument12 pagesIt Is Amazing How Quickly The Kids Learn To Drive A CarGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- Ancient IndiaDocument593 pagesAncient IndiaGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- Pranjal - Sociology ProjectDocument22 pagesPranjal - Sociology ProjectGhanashyam DevanandNo ratings yet

- Claim and Adjustment LettersDocument9 pagesClaim and Adjustment LettersHuyền HàNo ratings yet

- 2015 - 30 June - Synaxis of The ApostlesDocument6 pages2015 - 30 June - Synaxis of The ApostlesMarguerite PaizisNo ratings yet

- Rizal and The Origin of Filipino RaceDocument6 pagesRizal and The Origin of Filipino RaceLei Franzie Aira OlmoNo ratings yet

- Du a before and after studyDocument5 pagesDu a before and after studyaisha__No ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of Ulip Plan of HDFC Standard Life Insurance & Icici Prudential Life InsuranceDocument10 pagesA Comparative Study of Ulip Plan of HDFC Standard Life Insurance & Icici Prudential Life InsuranceSagar DwivediNo ratings yet

- Max HuberDocument4 pagesMax HuberRaji PunjabiNo ratings yet

- 4-Article Text-18-1-10-20181107 PDFDocument353 pages4-Article Text-18-1-10-20181107 PDFFaldi PurasongkaNo ratings yet

- ITC Slot AdherenceDocument40 pagesITC Slot AdherencehhgakNo ratings yet

- British Culture 1Document21 pagesBritish Culture 1Kiều TrangNo ratings yet

- Law of AdditionDocument2 pagesLaw of Additionapi-559330980No ratings yet

- Nilai Fitokimia Reg A StudentsDocument8 pagesNilai Fitokimia Reg A StudentsCicih AprilianaNo ratings yet

- Famous PainterDocument2 pagesFamous PainterChristian James LimpahanNo ratings yet

- When Britain Went Pop! - Christie's and Waddington Custot Galleries Present The First-Ever Exhibition of British Pop Art in LondonDocument3 pagesWhen Britain Went Pop! - Christie's and Waddington Custot Galleries Present The First-Ever Exhibition of British Pop Art in LondonGavelNo ratings yet

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris PetaDocument8 pagesTugas Bahasa Inggris PetaDewi PuspaNo ratings yet

- Manila South CemeteryDocument1 pageManila South CemeteryJake CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Vida CardDocument18 pagesVida CardAli AnaNo ratings yet

- Badan BeruniformDocument50 pagesBadan BeruniformLIM CHIN GUANNo ratings yet

- Replacement of LV Panel and Power CablesDocument16 pagesReplacement of LV Panel and Power Cablessepta ibnuNo ratings yet

- Oscar Ii FredrikDocument4 pagesOscar Ii FredrikMiguel AngelNo ratings yet

- Contoh kalimat tanya past tense dari:-They went to Tokyo last month.Did they go to Tokyo last month? -She went home two minutes ago.Did she go home two minutes agoDocument6 pagesContoh kalimat tanya past tense dari:-They went to Tokyo last month.Did they go to Tokyo last month? -She went home two minutes ago.Did she go home two minutes agoRonaldi Saputra100% (1)

- Edited Ap3 Second Test 40 Items Sy 19 20Document5 pagesEdited Ap3 Second Test 40 Items Sy 19 20Chantal Anne Sicat TulabutNo ratings yet