Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BCAS Vol 5 Issue 1

Uploaded by

Len HollowayOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BCAS Vol 5 Issue 1

Uploaded by

Len HollowayCopyright:

Available Formats

Back issues of BCAS publications published on this site are

intended for non-commercial use only. Photographs and

other graphics that appear in articles are expressly not to be

reproduced other than for personal use. All rights reserved.

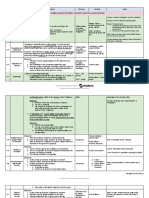

CONTENTS

Vol. 5, No. 1: July 1973

Gail Omvedt - Gandhi and the Pacification of the Indian National

Revolution

Carl Riskin - Maoism and Motivation : Work Incentives in China

Eqbal Ahmad - South Asia in Crisis and Indias Counterinsurgency

War Against the Nagas and Mizos

Gabriel Kolko - The Philippines: Another Vietnam?

David Rosenberg - The End of the Freest Press in the World

Secretary of Public Information - Guidelines for Mass Media

Philippine Social Science Council - Suggested Guidelines for

Philippine Scholarly Journals

Fred J. Elizalde - Propagating the Ideas of the New Society

Richard Kagan and Norma Diamond - Solomons Maos Revolution

and the Chinese Political Culture / A Review

Moss Roberts - Scotts The War Conspiracy / A Review

CCAS and Ezra Vogel - The Funding of China Studies

BCAS/Critical AsianStudies

www.bcasnet.org

CCAS Statement of Purpose

Critical Asian Studies continues to be inspired by the statement of purpose

formulated in 1969 by its parent organization, the Committee of Concerned

Asian Scholars (CCAS). CCAS ceased to exist as an organization in 1979,

but the BCAS board decided in 1993 that the CCAS Statement of Purpose

should be published in our journal at least once a year.

We first came together in opposition to the brutal aggression of

the United States in Vietnam and to the complicity or silence of

our profession with regard to that policy. Those in the field of

Asian studies bear responsibility for the consequences of their

research and the political posture of their profession. We are

concerned about the present unwillingness of specialists to speak

out against the implications of an Asian policy committed to en-

suring American domination of much of Asia. We reject the le-

gitimacy of this aim, and attempt to change this policy. We

recognize that the present structure of the profession has often

perverted scholarship and alienated many people in the field.

The Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars seeks to develop a

humane and knowledgeable understanding of Asian societies

and their efforts to maintain cultural integrity and to confront

such problems as poverty, oppression, and imperialism. We real-

ize that to be students of other peoples, we must first understand

our relations to them.

CCAS wishes to create alternatives to the prevailing trends in

scholarship on Asia, which too often spring from a parochial

cultural perspective and serve selfish interests and expansion-

ism. Our organization is designed to function as a catalyst, a

communications network for both Asian and Western scholars, a

provider of central resources for local chapters, and a commu-

nity for the development of anti-imperialist research.

Passed, 2830 March 1969

Boston, Massachusetts

I

i

GailOmvedt

I

!

Carl Riskin

I

Eqbal Ahmad

I

John F. Hellegers

I

1

I

Gabriel K olko

David Rosenberg

Secretary of Public Information

Philippine Social

I

Science Council

I

Fred J. Elizalde

I

Richard Kagan &

Norma Diamond

Moss Roberts

CCAS

Ezra Vogel

CCAS

~ o D t e D t 8

2 Gandhi and the Pacification of the Indian

National Revolution

10 Maoism and Motivation: Work Incentives in China

25 Further Notes on South Asia in Crisis/with an Account of

India's Counterinsurgency War Against the Nagas and Mizos

37 Chloramphenicol in Japan: Let it Bleed

46 The Philippines Under Martial Law

47 The Philippines: Another Vietnam?

53 The End of the Freest Press in the World

58 Guidelines for Mass Media

59 Suggested Guidelines for Philippine Scholarly

Journals

60 Propagating the Ideas of the New Society

Reviews

62 Father, Son, and Holy Ghost: Pye, Solomon and the

"Spirit of Chinese Politics"

68 Watergate International Unlimited: Peter Dale

Scott's The War Conspiracy

Funding of China Studies, Continued

72 Resolution (1972) on Funding of Asian Studies and

Contemporary China Studies

72 Communication

74 The J CCC Boycott: A Necessary First Step Towards

Self-Determination in Asian Studies [1973 resolution)

76 Contributors

Editors: Steve Andors/Nina Adams Managing Editor: Jon

Livingston Book Review Editor: Moss Roberts Staff for this

issue: Helen Chauncey/Betsey Cobb/Mary-Beth Coleman/Bob

Delfs/Steve Hart/Ted lIuters/Hal Kahn Editorial Board: Rod

Aya/Frank Baldwin/Marianne Bastid/Herbert Bix/Helen

Chauncey/Noam Chomsky/John Dower/Kathleen Gough/

Richard KaganlHuynh Kim Khanh/Perry Link/Jonathan

MirskyIVictor Nee/Felicia Oldfather/Gail Omvedt/James Peck

/Franz Schurmann/Mark Selden/Hari Sharma/Yamashita

Tatsuo.

BULLETIN OF CONCERNED ASIAN SCHOLARS, July 1973, Volume 5, number 1. Published quarterly in spring,

summer, fall, and winter. $6.00; student rate $4.00; library rate $10.00; foreign rates: $7.00; student rate $4.00. Jon

Livingston, Publisher, Bay Area Institute, 604 Mission St., San Francisco, California 94105. Second class postage paid at

San Francisco, California.

Copyright Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 1973.

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

Gandhi and the Pacification of

the Indian National Revolution

by Gail Omvedt

Introduction: Modern India and

Gandhian Nonviolence

Recently in Dhulia district in the state of Maharashtra in

western India an exploited semi-tribal population of Bhils have

mounted a revolt against their wealthy high-caste landlords.

Oppressed by indebtedness, landlessness and unemployment,

harassed with floggings and rapes by landlords, and provoked

finally by the murder of a Bhil farm laborer by armed

landlords in May 1971, the Bhils have mounted an increasingly

intense and organized struggle. They have participated in

conferences calling for cancellation of debts, reclamation of

lands, and minimum wages for agricultural laborers; they have

moved into action including forcible harvesting of crops and

occupation of lands that had been legally theirs before being

expropriated by the landlords. In the 1972 elections which

brought an overall victory to Prime Minister Indira Ghandhi's

Congress party, a boycott in the Bhil areas resulted in only an

8% turnout at the polls.

The struggle in Dhulia is not unique. It is one local

version of the rising class conflict in India between the

landlords and rich peasants who have benefited from recent

technological improvements in Indian agriculture, and the

poor peasants and landless laborers whose position has in

many areas steadily worsened.

l

What is unusual about the

struggle in Dhulia, however, is that the leadership of the

movement has brought together cadres of a Maharashtrian

communist party with an increasingly radicalized local

leadership of the Sarvodaya, the primary "Gandhian"

organization of independent India.

The leader of the Sarvodaya left, Ambarsingh Maharaj

Suratvanti, is himself a Bhil who became known as a

nonviolent social reformer in a semi-religious tradition.

Ambarsingh and others of the local Sarvodaya group have

shifted their emphasis from traditional welfare activities

focusing on schools, health centers, and campaigns against

alcoholism to a recognition of the inevitability of struggle. 2

But the Indian Sarvodaya as a whole has simply reflected

the developing class tensions in the countryside rather than

taking decisive leadership in promoting the demands of the

poor. Although some of the organization's top leaders have

formally recognized the existence of class struggle,

3

the district

and state leadership of the Sarvodaya in Maharashtra in fact

attempted to expel Ambarsingh for his militant actions; when

this failed, the right-wingers themselves resigned. And it is

noteworthy that this occurred in a situation in which the left

Sarvodaya group had moved simply to the stage of advocating

militant but peaceful struggle.

Two closely linked factors appear to be involved in this

Sarvodaya conservatism regarding social revolutionary struggle.

On the one hand, there is a social conservatism arising from

the class background of the leadership, itself a result of the

development of the movement. On the other, there is a

genuine philosophical dilemma of nonviolence: the continuing

threat of violence against poor peasant movements, the

possibility and increasing reality of their militant resistance,

and the necessity of working in such struggles with communist

organizations define a situation in which at every crucial point

increasing radicalism threatens to transcend the limits of

nonviolence.

Is a nonviolent revolution possible? The very question

illustrates the degree to which demands on nonviolence as a

form of action have escalated. Once people have decided to

take revolution, a total change in the social structure leading

to a society of justice and equality, as the goal, it is no longer

enough to argue that nonviolence is moral in the immediate

sense, i.e. that it is the only morally pure form of action for an

individual. It is no longer even enough to argue that it is only

nonviolence which will produce the kind of revolutionary

society we want-since it is obvious to most, at least, that

violent revolutions have in fact led to societies in China and

elsewhere that, whatever their imperfections, represent an

undeniable social and moral advance over the pre-revolution

ary situation. It is necessary now to show that nonviolence is

the most moral form of action at a social level and in the long

run: in other words, that it can be revolutionary, that it can

destroy the violence and oppression of existing social

structures. In terms of the analysis of Max Weber, nonviolence

must be justified in terms of an "ethic of responsibility" rather

than an "ethic of ultimate ends." 4

Up to now, nonviolent activists have responded to such

demands by pointing to Gandhi in India. Gandhi is the hero of

nonviolent revolution. Much has been written about him and

the techniques of Satyagraha; Africans as well as American

blacks have been influenced by the apparent success of the

2

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

Indian movement. Thus, just as India is sometimes seen as the

"democratic alternative" to Communism, so it is Gandhian

nonviolence that is seen as the alternative to costly, violent

revolutionary war.

Yet we see that the dilemmas of present-day Gandhian

activism in India represent simply a more heightened version

of nonviolent politics in America. Due to the excruciating

degree of poverty and oppression and the failure of economic

development to ameliorate the condition of the rural poor,

revolution appears more of a necessity. And because of the

existence of militant communist organizers-however divided

the Marxist left has been in India it appears infinitely stronger

and more mass-based than in the U.S.-revolution appears to

have greater immediacy. If Sarvodaya workers are to carryon

even peaceful struggle in the areas where it counts, in the

villages and settlements where the rural poor face their

landlords and the police power of the state, they must work in

conjunction with revolutionaries who believe that at some

point violence is inevitable. Thus we are faced with the irony

that in India, where Gandhian nonviolence exercised a stronger

hegemony over the national movement than in any other

movement in the world, it faces even greater dilemmas than

elsewhere in terms of social revolutionary struggle: neither

Gandhians nor socialists influenced by Gandhism can avoid the

contamination of violence, and a nonviolent revolution no

longer appears viable.

The reemergence of the class struggle in India since

independence and the resulting dilemma for Gandhians

suggests that is is necessary to re-examine the role of

Gandhism within India's independence movement itself. It is

necessary to go beyond the reams of literature which focus on

Gandhian techniques or on Gandhi as a person; it is crucial to

look at the social function which nonviolence has served in

India's long and continuing revolution.

The issue should be clearly posed. To the question, "Is a

nonviolent revolution possible?", Gandhians in India and

elsewhere have replied with a firm "yes." Nonviolent

techniques, in other words, have been justified not only in

terms of the "ethic of ultimate ends" put also in terms of the

"ethic of responsibility," the belief that nonviolence can lead

to a revolutionary new society. Behind this belief has been an

ideology that represents the particular Gandhian version of

class harmony, which assumes that there is in some

fundamental way and at some level a harmony of interests

between the contending forces within society, that at some

point the ruling classes will pull back, will refrain from using

their forces of destruction.

This Gandhian denial of class struggle and thus of the

inevitability of violence is in strong contrast with the

arguments of Mao, as stated in his famous report of peasant

movements in Hunan, that "proper limits have to be exceeded

in order to right a wrong, or else the wrong cannot be

righted." 5

If Mao is right (and we would argue he is), Gandhian

nonviolence could achieve one form of success in attaining

formal independence from the British precisely because such

harmony of interests did exist between the Indian elite and

their foreign rulers: the British could pull out and leave the

elite in charge of the system they had constructed with the

assurance that no nationalization of economic enterprises

would take place and that India would not pull out of the

"free world" system. But this harmony did not exist between

Indian workers and capitalists, between Indian peasants and

moneylender landlords, or between the low castes (especially

Untouchables) whose very humanity depended on the

destruction of the caste system and the high castes (especially

Brahmans) who lived off the system. To act on the basis of a

believed harmony that does not exist is to act ultimately in the

interests of the status quo which proclaims that harmony and

which advertises that capitalism (reformed) and Hindu caste

culture (reformed) are ultimately in everyone's best interests.

It is to act in contradiction with reality-and the fact that

Gandhi himself fell victim to these contradictions (assassinated

by a conservative Brahman) should not blind us to the fact

that the Indian people have been victimized by the

unwillingness of their leadership to go beyond "proper limits"

in order to "right a wrong."

The argument of this paper is that the social function of

Gandhian nonviolence in Indian history has been to allow

India to achieve a political revolution (formal independence)

without having a social revolution. Gandhi's control of the

movement was directed not only at achieving independence

from Britain, but also at pacification of the Indian revolution

itself.

Gandhi did not mobilize the "traditional" or

"backward" masses of India into a disciplined national

movement; rather he mobilized masses who were already on

the move into the control of a Congress party dominated by

bourgeois and upper-caste Indians. And it is this conservative

consolidation of the Indian national movement (compared to,

for instance, China's revolutionary consolidation) that has left

the masses of the population still immersed in poverty and

caste degradation.

6

We will look at three aspects of the Indian national

movement. Several misimpressions seem to be rampant among

foreigners (including many scholars) about this long struggle.

First, it is usually thought that Gandhi's role was to arouse the

masses of peasants and workers, who are seen as not only

poverty-stricken but backward and tradition-bound, capable of

being mobilized for struggle only by that unique combination

of traditional Hindu saintliness and nationalist aspiration that

Gandhi offered.

7

Second, it is thought that independence was

mainly achieved by means of the successes of Gandhi's

nonviolent campaigns. Third, Gandhi is thought to have played

a crucial and innovative role in linking social reform (the

abolition of untouchability) with political goals. These issues

will be taken up in turn.

The Indian Masses and the National Movement

When Gandhi returned to India from South Africa III

1915, it was clear that the Indian Congress party was an

organization of the elite-mainly Braham professionals and a

few upperclass merchants, men whose dress, language

(Congress sessions were conducted in English), and style of life

indicated their separation from the masses. Many of this elite

were fervent nationalists who had been driven to militant

actions and terrorism against the British, but mass organization

was non-existent. "A few lawyers and merchants in each

town," was how one old nationalist leader described the

organization of the Congress party up to 1930. There is no

question that Gandhi recognized the need of going beyond this

to identify with the Indian masses in style of life, and there is

no question that in his period of control the Congress party

3

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

widened its organization, sinking roots in the villages

themselves as well as gaining solid financial support from

Indian capitalists. But that is not the point.

The point is rather than the Indian masses had not

remained apart from the Congress due to their

"traditionalism" and lack of nationalist aspirations. They had

remained apart because they distrusted the Indian elite.

Organizations calling for the abolition of the caste system had

been formed In the 19th century, even before the

establishment of the Indian National Congress itself.

Untouchables and low-caste Hindus had brought their

demands to Congress sessions, and, rebuffed, had retreated

into sullen indifference.

8

By the 1920's anti-caste non Brahman

movements were strong especially in southern and western

India. Where low-caste members gained a significant foothold

within a local Congress organization (as in Kerala), they turned

its attention to caste reform issues such as temple-entry

movements. Where they did not (as in Maharashtra and

Madras) they organized separately and denounced the national

movement, saying that they preferred British rule to Brahman

rule.

We can trace a similar development with peasant

uprisings. The initial disruptions of British conquests and land

settlements caused numerous Indian peasants to lend their

support to the essentially feudalist-led, army-based Revolt of

1857. Then in the last half of the nineteenth century sporadic

peasant rebellions occurred (the Deccan riots of 1875, the

Santhal rebellion, the Indigo cultivators' "blue mutiny") that

had only tenuous connections with the nationalist elite. The

Congress policies of the late 19th century not only had no

relevance to peasant needs but actively opposed attempts of

the government to protect tenants against landlords or

moneylenders. Then in the crucial 1920's, once again, the

resurgence of peasant movements forced attention to their

needs upon the Congress. The noncooperation campaign of

1920-21 was fed by agrarian revolt, especially in Uttar Pradesh

(then the United Provinces) and Bihar and to a lesser extent in

Bengal. Peasant leagues were formed, often with the initial

support of local Gandhian or nationalist leaders and with the

use of Gandhi's name as a symbol, but they quickly developed

their own momentum, showed their ability to maintain an

organization independent of Congress initiative, and turned

their attention to direct attacks on landlords. It was Gandhi's

inability to control such deepening radicalism in the context

of the common interest between upper-class Congress leaders

and the government in dampening agrarian revolt that lay

behind his decision to call off the noncooperation campaign

over the issue of the killings at Chauri Chaura.

9

Finally, the 1920's, in India as in other crucial parts of

the colonized Third World (China, South Africa), saw an

intensification of working class struggle. Wave after wave of

strikes occurred, older reformist labor-welfare leaders were

denounced, and true unionizing began for the first time, often

under communist leadership. It was one of these working class

leaders, A. A. Alve, a Bombay cotton mill worker and

ex-peasant, who expressed most clearly the radicalism and

disillusionment of the lower classes. Speaking of the Congress,

he said,

If its demands from the first are examined, it will be seen

that it is an institution brought into existence in order to

carryon negotiations with the Government on behalf of

India. It will be seen that among the first demands . .. no

demands were made for the peasant and work er class. If the

resolutions of the Congress hereafter are seen, these

demands appear to have been made .. . for the factory

owners, landlords, and some only for the educated class . ..

When the noncooperation movement began, he testified, he

himself had taken part due to belief that workers' needs would

be placed before the people. There was a declaration of rights

for the people at the Karachi Congress session (1931), but

then landlords and industrialists raised an outcry and Congress

promised to protect them: "From this it came to our notice

that the National Congress was not for our welfare." 10

As Alve put it, workers had understood swaraj (freedom)

to mean that moneylending would stop, land would be

cheaper, and oppression by factory owners would cease. In

other words, by the 1920's peasants and workers were on the

move in India, there was a strong and growing force for social

revolution-and the masses interpreted independence to mean

the end of British rule and Brahman rule and the oppression of

moneylenders, landlords and capitalists. The question was not

whether these forces of social revolution would be combined

with the national movement, but whether they would be

combined in a way that allowed them control over the

emerging nationalism or whether they would simply be

coopted by the upper-class and upper-caste elite that had run

the Congress party from the beginning. And in fact Gandhi

whose best friends (as he himself stated) were industrialists

and Brahmans, was the agent of that cooptation.

The Congress under Gandhi did sink its roots into the

villages, but unlike the Chinese Communist revolution which

organized its villages from bottom up with a poor peasant

base, the Indian party mobilized from the top down. Gandhian

adherents and activists at the village level were most often

drawn from the Brahman and merchant castes (the lower-level

equivalents of the Congress top leadership) and from rich

peasants who saw their interests becoming congruent with the

movement. It was simply not natural for them to support

social revolution at either a village or national level. It is

misleading to talk of Indian leaders being corrupted by power

and deviating from Gandhian ideals after independence: the

electoral machine with left-wing rhetoric that is the Congress

today was created during the Gandhian period.

Gandhi's genius was that he really understood what was

necessary in India-but he used that understanding against

social revolution. It was not his religious revivalist rhetoric that

brought in the masses, but the fact that he managed to

identify himself with every single social movement going on in

India at the time, while using this identification to "pacify"

those movements. Thus he helped to form a labor union in

Ahmedabad but emphasized class harmony and the

"trusteeship of owners" 11 and refused to let that union take

part in all-India union federations. He identified with peasants

by leading no-tax campaigns against the Government but

consistently refused to let those turn into no-rent campaigns

against Indian landlords and resisted the formation of

independent Kisan sabhas or peasant leagues. And he

identified with the movement against caste by arguing for the

abolition of untouchability while trying to maintain the

essentials of an idealized caste system and opposing most

independent efforts by Untouchables.

4

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

Nonviolence and Mass Uprisings

in Indian Independence

Many factors played a role in the long and varied

struggle that finally resulted in formal independence for India:

constitutional agitation, elite terrorism, civil disobedience and

satyagraha, mass uprisings, and mutiny in the armed forces. To

understand the role of anyone of these it is necessary to look

at the total context of the movement. While it is impossible to

give a. full analysis here, it may be argued that all of the

famous all-India independence campaigns under Gandhi's

leadership (the noncooperation movement, the civil

disobedience campaign of 1930, the Quit India movement of

1942) illustrate the ambiguities in practice of Gandhian

nonviolence. In each case Gandhi's efforts at mass

mobilization threatened to arouse energies which he could not

control-energies often provoked by the greater social

radicalism of local leaders. Gandhi's subsequent efforts to

control the uprisings (and his associated reluctance to lead

campaigns that would arouse them) involved a dampening not

only of the forces of social revolution, but of the nationalist

movement itself. At the same time, it was the continuing

threat of real revolt underlying Gandhi's carefully toned

campaigns that stimulated the British in the end to cede power

through negotiations.

A couple of examples might give an idea of the mass

pressures which the Congress leadership, as well as the British,

had to confront. In Satara district of western India, there was

a young man of peasant background, Nana Patil, by profession

a minor village accountant. He was an ardent social reformer,

he taught his wife to read, urged cheap weddings and

supported the nonBrahman movement which itself

occasionally broke into violence against priestly dominance

and landlord power. When the civil disobedience campaign of

the 1930's came along, he became an ardent nationalist,

shouting "Long Live Gandhi!" and taking up the Congress

flag. But as a Gandhian he was distinctly unsatisfactory: his

concern with arousing the people led him to avoid arrest and

his many hair-raising escapes from the police gave him local

renown. He flirted with the idea of armed opposition; as his

biographers put it, "the satyagrahi had become a Maratha

guerrilla. " 12

Though he was arrested several times in proper Gandhian

fashion, he was not in the good graces of the higher-level

Congress leadership. When at one time in the 1920's he was

interned in a particular district by the British, the local

Congress committee refused to give him a minimal three

rupees a month for food. When they slammed the door in his

face, he was forced to seek support from his friends among the

poor, who developed bitter feelings about the upper-class life

style of local Congressmen and self-professed Gandhians who

wanted the masses to stick to their simple diet and not see the

"decadence" of higher living.

Then came 1942 and the rousing call from the Congress

"high command" for the British to "Quit India!" Though

Gandhi and the leadership had only reluctantly organized the

campaign and first conceived of it only in the limited terms of

"individual satyagraha" there was tremendous mass response

throughout India. In Satara district, as in some other districts,

this took the form of a full uprising, including burning British

government buildings, cutting telegraph lines, robbing trains,

and the establishment of a "parallel government" that remains

legendary today. But these mass rebellions were not organized

by the Congress party. Gandhi and other Congress leaders had

been jailed before a civil disobedience campaign could be

launched, and while in jail he launched a 21-day fast protesting

British charges that he was responsible for the violence; had be

been left free, he would have been able to moderate the

movement. 13

Congress socialists did support such activities and in

some cases took part in guerrilla actions themselves, but they

did not organize the rebellion: being mostly upper-class

Brahmans themselves, they had little mass support. The

communists, finally, were isolated from the national

movement by their support of the British war effort at this

time. The mass rebellions were in fact largely spontaneous

peasant uprisings. It was Nana Patil who was the hero of the

"parallel government" of Satara, and its organizers were young

men of peasant background who only later became leaders and

politicians within the Congress or other more left-wing parties

(Nana Patil himself became, after 1948, a communist).

In 1946 another momentous event occurred which

threatened that ultimate mainstay of British rule, the military.

Ratings (servicemen) of the Royal Indian Navy rose in mutiny

and a total strike ensued: 74 ships, four flotillas, and twenty

shore establishments, including four major bases around

Bombay harbor, were under control of the rebels. Strikes

began to spread in the air force, unrest was intensifying in the

army, and the working classes of Bombay took to the streets

to be killed by British guns in the most violent episode of the

independence movement.

But no leadership came forth from either Congress or

communist leaders to support or coordinate the seizure of

military power: the nationalist leaders did not want such a

revolt. As one of the leaders of the mutiny writes,

We had thought that all we had to do after the take-over of

the Navy was to report to the national leaders . .. The

R.l.N. was offered to them as the Indian "National Navy"

on a platter. The leadership would not touch it! It was

shocking. We felt bewildered, dispirited and humiliated. We

had captured the ships alright but where does one find a

navigator? .... When news of the "disturbances" reached

Mahatma Gandhi-he was in Poona then-he casually told

his evening prayer meeting that if the ratings were unhappy

they could have "resigned. "! An unfaltering practitioner of

nonviolence, the Mahatma had tried to teach his followers the

efficacy of his chosen path for aecades and had seen to it

that all those who did not fall in line with him were kept

out of the national liberation movement. Our mutiny smelt

of violence. And that ended all argument. Whether the

ratings were in a position to resign at all was a peripheral

matter. ... 14

The national leaders joined with the British in stating that the

rebellion was not really "political" but only "economic," that

servicemen were concerned only with such minor conditions

of life as the quality of their food. They "reassured" the men

that they would support their "just grievance"-and urged

them to surrender to the British. The organizers of the most

effective revolt against British state power afterwards sank into

obscurity, their contributions unrecognized within indepen

dent India.

The civil disobedience campaigns of the Indian national

movement have been well publicized; other mass uprisings

5

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

such as the R.I.N. mutiny and the Satara "parallel

government" have remained little known outside of India.

These mass rebellions were spontaneous in the sense of being

fed by deep feelings of oppression on the part of the people

and in not being led by any ideologically organized party.

More important, they threatened more than the British: the

R.I.N. mu tiny was a threat to the state itself and authority

within the armed services, and the peasants of Satara and

elsewhere turned their wrath against Indian landlords and

collaborators as well as British bureaucrats. Thus the way in

which the National Congress leadership sought to direct the

national movement has led many to ask whether Gandhi's

concern to avoid "violence" against human life was not in fact

a concern to avoid mass attacks on elite privileges and the

institutions of authority.

Perhaps they may have come to the latter conclusion

from events in the late 1930's. In 1937 Congress governments

were elected throughout India; in Bombay province this

government was largely under control of Gujerati capitalists

and Maharashtrian Brahman intellectuals, and laws were passed

that were felt to be against peasant and working class interests.

While strikes of workers in Bombay were suppressed by the

police, peasants in many parts of the state held rallies and in

the northern districts a huge march and demonstration was

planned under a mixed leadership of radical local Gandhians

and Communists. Gandhi attempted to stop the march, wiring

the leaders that it was "violence" to oppose their own

Congress government. 50,000 peasants eventually marched,

but their original intention to march on the government office

was compromised to a rally in the market area. IS Gandhi's

attempt to halt the Maharashi:rian peasant march was

consistent with his resistance throughout this period to the

formation of independent leagues of Kisan sabhas, for as the

Congress leaders saw it,

There were the hordes of Kisans organizing themselves into

huge parades marching hundreds of miles along the villages

and trying to build up a party, a power and a force more or

less arrayed against the Congress . ... The flag they chose to

favor was the Soviet flag of red colour with the hammer

and sickle. This flag came more and more into vogue as the

flag of the Kisans and the Communists, and even loud and

repeated exhortations of Jawaharlal Nehru would not keep

it to its place or proportions. Almost everywhere there were

conflicts between Congressmen and Kisans over the

question of the heigbt and prominence of the flag, and the

virtual attempt of the latter to displace tbe Tricolour flag

symbolized the contest between Socialism and Gandhism.

Really it was less of Socialism and perhaps more of

Communism that was gradually permeating the at

mosphere . ... 16

Gandhi as the friend of capitalists and Brahmans,

attempting to pacify and control mass uprisings throughout

India-this is a less attractive picture than Gandhi the saintly

politician, living in slum areas, traveling third class on the

trains, and sweeping out village Untouchable quarters. Yet

both pictures are true and necessary for an understanding of

the role of Gandhian nonviolence in India. Gandhi's fear of

violence was in large part a fear of the chaos he perceived as

threatening the structure of Indian society and the position of

the Indian elite if mass energies were not controlled. 17 I Ie had

no doubt that the Congress ministry was a government of the

people and that the Indian elite could act as "trustees" of mass

interests. The function of nonviolence-the well-organized civil

disobedience campaigns, the image of the social reformer living

among the masses was to make this aspiration believable. And

it was made believable-for a time. Helped out by the

intelligent willingness of the British to compromise with the

Indian upper classes and the failings of communist or socialist

organizers, Gandhi managed to establish Congress as a "mass"

organization linked to village elites throughout the country.

The result was the pacification of the Indian revolution. For a

time.

Gandhi and the Revolution Against Caste

Isn't this a bit unfair to Gandhi? it may be asked. After

all, wasn't it one of his unique characteristics as a national

leader that he linked independence to reform of Indian society

from within by making the removal of untouchability a

primary part of his program? Wasn't he a social revolutionary

in fighting the caste system, the major cultural form of

oppression of the Indian masses?

IJere again it is necessary to look at the Indian context, a

context in which a revolution against the caste system was

being initiated by low-caste non Brahmans and Untouchables

themselves. In fact, at the time Gandhi returned to India, there

were three major ideological thrusts regarding caste.

The first was the orthodox position, which looked on

the caste hierarchy as sacred and urged that it was the duty of

every Hindu to follow the caste profession of his birth. IS The

second position was that of the Arya Samaj, a religious reform

organization with large-scale support of urban and rural middle

castes of northern India. The Arya Samaj urged support of

varnashrama dharma-the four varna categories of brahman

(priest, intellectual), ksatriya (warrior), vaishya (businessman)

and shudra (servant of the other three varnas, i.e. the

masses)-but felt that this system, a creation of the Vedic

"golden age," had become decadent in modern India. It

therefore urged that the thousands of existing castes should

become merged within their appropriate varna category. It also

conducted shuddhi movements by which converts to other

religions and to a lesser extent Untouchables could be

"purified" and brought back to Hinduism. It tended to argue

that in the Vedic age varna positions had been by merit and

not by birth, and the more radical people associated with this

tradition argued that in the modern era position should also be

by merit.

The third position was the revolutionary one and found

its social basis in western and southern India among

nonBrahmans and Untouchables (though an early elite

organization of Bengal, the Brahmo Samaj, had been a pioneer

in social radicalism). Its primary organizational carriers were

the Satyashodhak Samaj ("Truthseekers Society") of

Maharashtra and the Self-Respect movement of Madras. This

position was a radical and equalitarian one, arguing that all

men were equal and that the caste system must be totally

abolished. Since all were equal before God (its more radical

members later took an atheistic position) there was no need

for a priestly intermediary. The organizations therefore

conducted campaigns to hold weddings and other religious

ceremonies without Brahman priests. The most interesting

aspect of this situation is perhaps that the most radical,

6

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

equalitarian and rationalist position found its mass basis not so

much among the western-educated elites of India as among

village level peasants, contrary to commonly held beliefs about

the "traditionalism" of the Indian masses.

How did Gandhi respond to these great debates

regarding the form of Indian society? It is important to note

that he was responding to them, not developing his position in

a vacuum. The primary source on Gandhi's ideas on caste is a

small book, My Varnashrama Dharma, published by the

Sarvodaya society and available today in bookstores, on Indian

railway platforms, and elsewhere. It contains articles Gandhi

wrote on the subject of caste in his newspapers between about

1920 and 1940; and a good third of these were directly in

response to non Brahman challenges. Many others bear the

mark of an indirect response to the movement against caste.

The position that Gandhi took was somewhere in

between the orthodox one and that of the Arya Samaj, though

he moved increasingly toward the latter. That is, he responded

to the revolutionaries' attack on the caste system as its liberal

defender. He urged that the system be updated, that its

hierarchichal feelings of superiority and inferiority be

abolished. He contrasted a decadent "caste" with an idealized

"varnashrama" system but he urged that the latter be

maintained. Sometimes he took halfhearted steps in the

direction of the notion that varna position should be by merit

and not by birth, but most often he urged that people should

follow their father's professions. Finally, in arguing for the

abolition of untouchability, he urged that Untouchables be

absorbed in the great shudra category-that is, among those

who were the lowest of the four varnas, who were the masses

working for the elite.

19

For Untouchables who were already

involved in movements demanding full human rights this was

an evasion.

Gandhi himself never led satyagrahas for the abolition of

untouchability or for the admission of Untouchables into

Hindu temples. Such satyagrahas did take place beginning in

the late 1920's, and some Gandhians and young Brahman

socialists did take part in them. But their major leaders were

Untouchables and non Brahmans who had emerged out of the

revolutionary anti-caste movements described above. India's

most famous Untouchable leader, the great Dr. B.R.

Ambedkar, always saw Gandhi and the National Congress as

responding to Untouchable demands only out of "political"

motives, a desire to prevent Untouchables from opting out of

the Hindu community. Dr. Ambedkar's book, What Congress

and Gandhi have Done to the Untouchables, should be on the

reading list of everyone concerned with either Gandhi or the

Indian movement.

Ambedkar, in fact, was Gandhi's antagonist in his major

fast over the question of untouchability. This was undertaken

in opposition to the decision of the Government of India to

give a separate electorate to Untouchables, i.e., certain seats

would be reserved to them in the legislatures and only

Untouchables would vote for their representatives. Gandhi saw

this as a major attack on the "unity" of the Hindu community

and threatened to fast to death in opposition. While this fast

took on the connotation of urging caste Hindus to reform

their ideas regarding untouchability (and its compromise was

afterwards seen as radical by the orthodox), in fact it was

primarily against the Untouchables' demand for separate

electorates and primarily against their acknowledged political

spokesman, Ambedkar. (Ambedkar later bitterly remarked

that while Gandhi had always claimed that the Congress was

the only representative of all Hindus, when it came to a

question of securing the real agreement of Untouchables they

turned to him, Ambedkar).

Pressure on Ambedkar to compromise was intense. For

all the moral aura surrounding satyagraha techniques, which

urged that they should win the freely given agreement of

opponents, moral blackmail was in fact the primary aspect of

this fast-to-death by Gandhi. Ambedkar was well aware of the

existence of Untouchables isolated and powerless in villages

throughout India and of the fury that would turn against them

if Gandhi died. He capitulated; a compromise was reached in

the "Poona pact" which gave the Untouchables an increased

number of seats but allowed caste Hindus as well to vote for

Untouchable representatives-and given the numerical

superiority of caste Hindus and the wealth and organization of

the Congress, this meant that Untouchables favorable to

Congress have been invariably elected.

Ambedkar died a bitter and disillusioned man, seeing

Nehru himself as "just another Brahman." His final verdict on

the Congress party, in the raw, rough language of the

non Brahman movement of the day: "Congress is the kept

whore of the Brahmans and merchants." The Untouchables'

temple-entry movements, usually unsuccessful, faded away. In

the end the most militant Untouchables became convinced

that there was no hope for them in Hinduism. Many of them,

under Ambedkar's leadership, converted to Buddhism; others

in more recent times have supported communist organization

of poor peasants and landless laborers. "Untouchability

removal" has continued to be a major plank of the Congress

party, but successes where achieved have been more the result

of direct Untouchable pressure than programs initiated by

Gandhians within Congress.

Gandhi has put forth his ideal for independent India as

"Ram Rajya," the kingdom of Rama, hero of one of the great

Hindu epics, the Ramayana. In choosing Rama as a symbol,

Gandhi no doubt found one that had a great appeal to many

Hindus, particularly in the north. But in south India, the Tamil

heirs of the nonBrahman movement see Rama as an Aryan

conqueror who had colonized and subjugated their people-the

Dravidian native inhabitants of the subcontinent. And in

western India, the Untouchables and non Brahmans I met had

another story from the Ramayana, the story of Shambuk.

Shambuk was an Untouchable boy in Rama's kingdom who

wanted to seek salvation by following Brahman paths of

asceticism and penance. But for an Untouchable to do so was a

sin, an infringement of the law of caste. Because of this "sin,"

a Brahman boy in Rama's kingdom died-and Rama executed

justice and maintained the order of castes by killing Shambuk.

"Who wants this Rama-Rajya?" was the response of

many Untouchables and non Brahmans. And it still is their

response.

This paper is based in part on research on a

peasant-based anti-caste movement carried out in Maharashtra

(western India) between January 1970 and August 1971.

Because of this, my illustrative examples are drawn primarily

from this region, where (in spite of the fact that it is

considered a Congress party stronghold today) some of the

oldest and strongest mass movements of India have taken place

and caste and class conflict was an undeniable fact. As a

7

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

personal note, it may be added that it is impossible not to feel

some sympathy and attraction for Gandhi, who was trying to

hold together so much that was at cross purposes in Indian

society. Particularly in my early days of research, when I was

reading the files of a nationalist but socially conservative

Brahman newspaper and became aware of the intense hatred

felt for Gandhi by a section of the Indian elite, this was my

feeling. It was only later, as I began to get deeper into the

historical records and closer to the people who had led

militant low-caste movements, people who had opposed and

pressured Gandhi from the left, that my view began to change

and I began to see Gandhi as primarily one of the most

intelligent members of that elite, involved in maintaining its

interests in the very process of leading a national movement

against the British.

NOTES

1. See for instance, Francine Frankel, India's Green Revolution

(Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1971), and Hari Sharma,

"Green Revolution in India: Prelude to a Red One?" Frontier, May 13,

20,27, 1972.

2. "The Bhil Movement in Dhulia," Economic and Political

Weekly, February 1972 (annual number); letters from Vasanthi Raman

and Yashwant Chavan. When I was in India, I attended a poor peasants

conference in February 1971 at which a Bhil spokesman made one of

the early appeals for support from the Lal Nishan (Communist) Party.

3. For instance, Shankkarao Deo; the result, however, was a

good deal of turmoil within the Sarvodaya organization; see Sharma,

May 13,14.

4. "Politics as a Vocation," in Hans Gerth and C. Wright Mills,

eds., From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1958),77-128.

5. Mao Tse-tung, Report on an Investigation of the Peasant

Movement in Hunan (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1967),9.

6. What is implied here is that without Gandhi's particular style

of leadership a more satisfactory outcome, and not simply social chaos

or a more virulent conservativism, would have been possible. Though

there were certainly factors other than Gandhi's role in preventing

radicalization (the repressive powers of the British government,

inadequacies of revolutionary leadership), I do believe the

possibility existed, though there is no space here to develop the

arguments.

7. Two recent works, however, represent a more realistic view;

see Judith M. Brown, Gandhi's Rise to Power (London: Cambridge

University Press, 1972) and Ravinder Kumar, ed., Essays on Gandhian

Politics: The Rowlett Act Satyagraha of 1919 (Oxford: Clarendon

Press, 1971).

8. See B. R. Ambedkar, What Congress and Gandhi Have Done

to the Untouchables (Bombay: Thacker & Co., 1955) and Chapter 8 of

my dissertation, "NonBrahmans Organize Politically" (Univ. of

California, Berkeley, 1973), for some of these developments.

9. See Walter Hauser, "The Indian National Congress and Land

Policy in the 20th Century" and John McLane, "Peasants,

Moneylenders and Nationalists at the End of the 19th Century," both

in Indian Economic and Social History Review, July-September, 1963;

W. F. Crawley, "Kisan Sabhas and Agrarian Revolt in the United

Provinces 1920 to 1921," in Modern Asian Studies 5: 2 (1971); John

Broomfield, Elite Conflict in a Plural Society: Twentieth Century

Bengal (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press,

1968),224-6.

10. Taken from his testimony in the Meerut Conspiracy Trials;

for a description of Gandhi's role vis-a-vis the Bombay workers, see

R. K. Newman, "Labour Organization in the Bombay Cotton Mills,

1918-29" (University of Sussex Ph.D. Dissertation, 1971), 147-8, where

he notes that during the Rowlett Act agitation Gandhi "privately told

the police he had no intention of bringing the millhands into his

movement 'for many a long day' and he promised to prevent his

assistants from stirring up unrest in the mill areas ... His local

lieutenants at first believed [Gandhi'sl strategy could take in a wide

range of social groups but the riots [following Gandhi's arrest 1 shocked

and disillusioned them. They lacked an organization to control the

workers and could not identify themselves with the economic issues

that were the workers' primary concern."

11. On the "trusteeship" ideology and its conservative

implications see Phyllis Rolnick, "Charity, Trusteeship and Social

Change in India," World Politics, April 1962. "Gandhi affirmed not

only that it was not possible to abolish class distinctions but also that it

was not desirable to do so ... According to [his] interpretation of

trusteeship .. wealth belonged to society as a whole, and it just

happened that some persons were in charge of the use of that wealth

for the whole society-i.e. they were trustees." (446-8)

12. Dr. Uttamrao Pati! and Appasaheb Lad, Krantivir Nana Patil

(Aundh: Usha Prakashan, 1947); biography in Marathi.

13. Louis Fischer, The Life of Mahatma Gandhi (New York:

Harper & Row, 1950),383-392.

14. B. C. Dutt, Mutiny of the Innocents (Bombay: Sindhu

Publications, 1971), 137-8.

15. Interview, Laxman Mistri; see also Pati! and Lad, Krantivir

Nana Patil, 66-67.

16. This is from the official history of the Congress party by

one of its Gandhian leaders; Pattabhi Sitaramayya, History of the

Indian National Congress, Volume 2, 1935-1947 (Bombay: Padma

Publications, 1949), 73; see the following sections for his description of

Congress efforts to control the peasant movement.

17. Here again it is important, though difficult, to separate

social conservativism (the fear that the masses would attack elite

privilege) from genuine issues of nonviolent revolutionary action (since

unorganized chaos or sporadic violent unrest does not by itself produce

revolution). Gandhi's fear of social chaos led him to limit the

movement, but how much was this an issue of nonviolence? It may be

noted that in cases of uncertainty of outcome, conservatives have

always put their values on "order," and Gandhi's fear and distrust of

the masses contrasts strongly with Mao's comments on the peasant

uprisings in Hunan, also a case of a popular movement over which the

mobilizing force (the Communist Party in this case) had only limited

control. Mao sharply attacked those who criticized peasant excesses:

"In a few months the peasants have accomplished what Dr. Sun Yat-sen

wanted, but failed, to accomplish in the forty years he devoted to the

national revolution. This is a marvellous feat. It's fine. It is not 'terrible'

at all. It is anything but 'terrible.' 'It's terrible!' is obviously a theory

for combating the rise of the peasants in the interests of the landlords."

Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan (Peking:

Foreign Languages Press, 1967), 6.

18. This is known as swadharma, "following one's own duty,"

with the definite meaning of a religiously-defined caste duty-and for

Westerners reading Indian literature it is a primary indicator of

supporting caste without openly saying so. Thus for example when

Vinoba Bhave, Gandhi's most revered follower today, urges swadharma

in his book Essays on the Gita, this is the context in which it should be

understood.

19. M. K. Gandhi, My Varnashrama Dharma, (Bombay:

Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1965), esp. 10, 15-16, 30-31, 118-51. For a

slightly different interpretation of Gandhi's view on caste see Dennis

Dalton, "The Gandhian View of Caste and Caste After Gandhi" in

Philip Mason, India and Ceylon: Unity and Diversity (Oxford

University Press, 1967). Dalton argues that Gandhi's interpretation of

varnashrama dharma as something different from the caste system took

on fully radical overtones by 1932 when he criticized restrictions on

interdining and intermarriage, but notes also that Gandhi always held to

the hereditary nature of varna-perhaps the most crucial issue.

I would like to thank Steve Hart and Hari Sharma for their

and criticism (If this paper.

8

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

aSian

144 PAGES of articles, short stories,

poems, photos, interviews and artwork by

Asian women. Includes Issei picture

brides ... Chinatown pioneer women ... the

family ... the Indochina Women's Conference

... politics ... identity ... an annotated

bibliography.

The journal is now available.

Issei Nomen arriving in America

(Compliments of JARP-Japanese-American

Research Project)

PRICE: $ 2.00 per copy

.25 handling charges

Please send your order and $2.25 with

your name and address to:

EVERYBODY'S BOOKSTORE

840 Kearny Street

San Francisco, CA

Money order or checks should be payable to

EVERYBODY'S BOOKSTORE. No cash, please.

9

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

Maoism and Motivation:

Work Incentives

In China

by Carl Riskin

Random House, Inc.

Visitors to China invariably comment on the energy and

zeal of the people they met there. Seymour Topping's

impression that "the basic needs of the people are being met

and the foundation is being laid for a modern industrial

country" he ascribes partly to "the energy exhibited

everywhere." 1 Business economist Barry Richman found that

Chinese industrial executives had a "high need for

achievement" and displayed "considerable zeal, dedication,

patriotism ... a deep sense of commitment and purpose." 2

These examples could easily be multiplied.

Yet by now even those whose acquaintance with the

country stops at the name of its Chairman have heard that the

ordinary incentives (as we know them) to work hard and well

have been drastically weakened in China. Moreover, this

alleged Maoist blindness to original sin is generally held

responsible for a record of dismal failure in economic

development efforts. As Edwin O. Reischauer cogently put it:

"I think Mao or else people close to him ... just did not want

to admit that people were people and were going to act like

human beings. That is one of the great failings of communism

everywhere. It has always tried to change people into

something else, and then it finds it cannot."

3

But if Mao ("or else people close to him") has failed in

his understanding of human nature, it follows that all the

Chinese managers with high need for achievement, all the

workers and peasants laboring on, despite the absence of

incentives, are either masochists or uniquely pliant subjects. In

other words, these two commonly held and widely expressed

views of the motivational atmosphere in China conflict with

one another.

Copyright 1973 by Random House, Inc. From the forthcoming book

on China edited by James Peck, Carl Riskin, and Franz Schurmann to

be published by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc. in

spring 1974.

In this article, I will argue that the assumptions implicit

in the experts' common wisdom regarding incentives in China

are naive and contradict well known and easily available

materials on motivation and work; that motivation is a crucial

variable in economic development although it is generally

neglected by economists; and that the Chinese approach to

motivation requires us to broaden our treatment of this

concept as well as to understand its links with other variables

such as organization, leadership and the distribution of

political power.

I. CHINA WATCHERS'

PERCEPTION OF MOTIVATION

It is difficult to grasp precisely what the critics of Maoist

incentive practices mean because of the vagueness with which

they habitually state their arguments, as though the latter were

self-evident and did not require careful exposition. Maoist

policies are characterized as obsessed with ideology and with

the use of moral rather than material incentives; these policies

are normally leavened with a sufficient dose of individual

material incentives to keep production going, but during

periods of extreme emphasis upon ideology (such as the Great

Leap Forward) the leavening disappears and morale and

production consequently suffer. Such, I believe, is a fair short

statement of the position of this school.

It is a position however which raises substantial

questions. What is responsible for good (or at least adequate)

work morale during "normal" periods-the material or the

nonmaterial incentives, or both? A separate though related

question is, what mix of material and moral incentives should

be regarded as "extreme" as opposed to 'normal"? I do not

mean that a precise payment scheme need be specified as the

border between these two conditions, but only that it is

necessary to identify an analytical basis for distinguishing

them. Otherwise, the argument reduces to a tautology,

namely, that extreme reliance upon nonmaterial incentives

causes morale and production to suffer, when the "extreme" is

defined as a state in which morale and production can be

observed to suffer.

10

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

One searches the literature in vain for satisfactory

answers to these two questions. One writer, for example,

asserts that "a minimum of incentives for the peasant

population" consists of location of the basic accounting unit

at no higher than production team level, existence of "free

plots," and functioning of rural free markets.

4

This is fair

enough, being presumably an empirical generalization from the

history of the last twenty years. But it lacks an underlying

rationale, ignores the question of how individual incomes are

distributed for collective labor, and fails to take into account

some well-known disincentives in locating the basic unit at

team level (e.g., that neighboring teams will differ substantially

in level of income per member simply because of differences in

soil fertility, or access to water-surely a cause for grumbling

among poorer team members). Moreover it is sustainable, if at

all, only for the specific conditions of a given historical period.

The most thorough study to date of the role of private plots in

Chinese agriculture concluded that their function would end

when the peasants have acquired "enough confidence that the

collective economy will supply their needs." 5

A common practice of the "pro-pragma" school is to

describe with value-laden adjectives the approach of Chinese

"pragmatists" opposed to Mao, thus implying that the Maoists

oppose these same values. For instance, the pragmatists

apparently recognize that effective management, scientific

and technical skills, and economic incentives are required

for success in economic development and modernization,

6

which implies that the Maoists wish to dispense with effective

management, scientific and technical skills and economic

incentives. Or,

The pragmatists-who doubtless include some of China's

leading administrators and technical bureaucrats-have

apparently been successful in demanding that economic

policies take account of economic realities 7

which implies that the "ideologues"-who have little or no

administrative or technical experience-demand in their turn

that economic policies ignore economic realities. Neither of

these points would be easy to support directly.

The penchant for criticizing undefined "extremes" is

illustrated in such statements as the following:

The anti-material incentive, anti-modern technology

mentality, if allowed full sway, will hinder the growth of

economy in general and of the modern sector in particular. 8

The difficulty with this statement lies not only in what I will

contend below is a mistaken view of the "mentality"

concerned, but also in the meaning of the picturesque term,

"full sway." The only passage offering a more specific idea of

what is being criticized is the following, which refers to "those

periods when the policy gave priority to ideology":

Since the accent was on an egalitarian spirit and

self-sacrifice, wages were not used as a proper stimulant to

improvement of skills and increased productivity. In rural

areas, this egalitarian tendency took the form of foodgrain

distribution on grounds mainly unrelated to either work

input or output. These irrational measures always cause a

drop or stagnation in production. 9

The writer apparently means that when wages are not

structured to stimulate improvement of skills and increased

productivity, skills will not be improved and productivity will

remain dormant; and when foodgrain is distributed in a

manner unrelated to the peasant's work input or productivity,

"a drop or stagnation in production" will ensue. Much of the

remainder of this paper will be devoted to showing that these

statements, far from being obvious on their face, beg most of

the important questions. Suffice it to say for the present that

there is no evidence that workers were not motivated to

upgrade skills during the Great Leap (introduction of

industrial technology to peasants during the "backyard iron

and steel movement" is one of the few generally conceded

virtues of that movement). Moreover, the contemporary

practice apparently widespread in rural areas of distributing

some foodgrain independently of work done

lo

has not caused

the predicted decline in production.

Perhaps the most thorough and specific critique of

"ideological extremism" IS that of Barry Richman.

11

According to Richman,

Ideological extremism in Chinese industrial management

seems to have four key prongs: These are (1) the Reds vs.

expert dilemma or pendulum; (2) material incentives and

self interest vs. non-material stimuli, altruism and

self-sacrifice; (3) "class struggle" and the elimination of

class distinctions; (4) the amount of time spent on political

education and ideological indoctrination. 12

In normal periods, experts are given more authority than Reds,

material incentives hold sway over altruism, class struggle is

muted, and people spend less time meeting and studying

instead of working. In "ideologically extreme" periods, the

opposite propensities dominate.

Richman's approach is unusual in that he finds value in

moderate progress toward the "ideological" ends of these

"prongs." "Management participation in labor at Chinese

factories does appear to have some favorable effects" in

"breaking down" deep-rooted antagonism and resentment

based on "class distinctions between managers and workers,

the educated and uneducated and mental and physical

labor." 13 But in general Richman treats "ideology and

politics," on the one hand, and "economic, managerial and

technical rationality," on the other, as two poles between

which a "pendulum" constantly swings.14 Moreover, he

considers swings to the left of the pendulum to be the greatest

single impediment to rapid industrial progress in China:

The types of constraints-both external and internal to the

enterprise-thus far discussed which tend to hamper

managerial efficiency and industrial progress in China {such

as lack of managerial skills, technical expertise, etc. -CRJ

appear to be but mere midgets as compared to the giant

constraints arising from ideological extremism. 15

Although Richman finds some pragmatic value in the use

of "ideology," more frequently he regards it as a utopian

attempt to fly in the face of "centuries of world history and

experience" by performing the "miracle" of replacing

"material gain" with "pure altruism" as the force motivating

man.

16

Such a description, I suggest, inaccurately portrays the

real problem of motivation in China and the current approach

to solving it.

11

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

Economics and Human Motivation

Economists are uncomfortable with the subject of

human motivation, despite its importance to economic theory.

Especially since the development of neoclassical economic

theory in the late 19th century, economists have tended to shy

away from serious consideration of the psychological and

sociological assumptions and implications of their work.

17

Instead, they have attempted to paper over the problem by

means of various treatments, which, however, turn out upon

closer examination to have strong and often simplistic

psychological assumptions at their roots.

18

While this may have

been possible in other branches of economics, there probably

would be universal agreement that it has no place in

development theory because it would remove the very essence

of the development process. This is a basic reason why this

sector of economics, unlike any other, has vigorously called

upon the aid of anthropology, sociology, and psychology in a

rare display of interdisciplinary cooperation.

However, the term "depsychologization" is indeed

accurate insofar as it pertains to the failure of economics to

inquire into (or utilize the results of others' inquiries into) the

nature and causes of human motivation lying behind the

choices with which economists concern themselves: between

work and leisure, between saving and consumption, and

between different combinations of goods and services. Instead

of analyzing the increase or decrease of production and growth

directly attributable to differentials in human commitment,

resourcefulness, energy and creativity, economic theorists have

traditionally avoided this problem by assuming given supply

schedules (a supply schedule is a relation between the quantity

of a good or service supplied and the price [or wage] offered

it) of resources, including labor, and then busying themselves

with the problem of achieving the most efficient allocation of

these resources among alternative uses.

There are grounds for believing that in making this

choice, economics has been guilty, by its own standards, of a

cardinal sin: misallocation of professional resources. For

empirical studies indicate that motivational factors are

responsible for incomparably greater variations in actual

economic performance than is allocational inefficiency. For

instance, Harvey Leibenstein concludes upon reviewing several

ingenious attempts in the literature to measure the loss in

national income which arises from misallocation of resources

that "empirical evidence has been accumulating that suggests

that the problem of allocative efficiency is trivial." 19 "Yet,"

Leibenstein continues, "it is hard to escape the notion that

efficiency in some broad sense is significant." This type of

efficiency "in some broad sense"-a major element of which is

"motivation"-he calls by the mysterious title of

"x-efficiency." 20

The dominant motivational component of "x-effi

ciency" is more familiar and less mysterious than that term

implies. It has been observed that "if you have some

quantitative measure of their contribution to the organization,

you will find that the best person in each group is contributing

two, five, or perhaps ten times what the poorest is

contributing." 21 The assumption that a substantial part of

such differences in performance among people doing the same

kind of work reflects differences in their motivation has

generated a voluminous literature on work motivation which

will be briefly touched upon below.

An almost identical case is made by Jaroslav Vanek.

Citing the same kinds of evidence used by Leibenstein, to

establish that misallocation of resources is generally

responsible for only negligibly small shortfalls in output,

Vanek points out that even multiplying these shortfalls many

times would not approach the several hundred percent

variation reasonably attributable to motivational factors.

22

"And yet, let it be noted, the time and concern of economists

devoted to the study of what we have identified here as effort

is of the order of one-thousandth" of that devoted to the

problem of allocational efficiency.23 Apparently, in identifying

man as "most precious" resource, in concentrating upon

activating the "boundless creative power" of the masses, in

urging that "spirit can become matter" and in teaching that "it

is people, not things, that are decisive," Mao has avoided the

economists' misallocation of mental resources, and eschewed

the "trivial" for the "significant." In other words, a key to the

Maoist conception of the development process lies in its search

for institutional forms of achieving the multi-fold increases

associated with human creativity and effort, rather than the

marginal increments associated with achieving optimal

allocation of statically conceived resources. 24

This formulation, of course, leaves open the question

whether Maoist antipathy to individual material incentives, by

contradicting human nature and the requirements of a modern

industrial society, renders the Maoist objectives utopian and

thus impossible to realize. The evaluation of this argument

requires a brief digression into motivation theory, and then the

development of a more adequate (if rudimentary) picture of

work motivation in contemporary China.

II. INSIGHTS OF INDUSTRIAL PSYCHOLOGY

Economists still commonly regard work as an unpleasant

trespass on leisure, necessitated by and supplied only because

of the need to earn income. From the viewpoint of the

worker, work is thus a "negative good," to which "disutility"

is attached, and to overcome this disutility and coax work out

of workers, a more than countervailing amount of "utility"

must be offered them in the form of purchasing power. Since,

furthermore, the amount of "disutility" is assumed to increase

faster than the number of hours worked, whereas the "utility"

per additional dollar of income falls as income increases, it is

easy to see why keeping up work efforts is thought to require a

highly progressive payment scheme.

This theory is not so naive as to assume that "leisure"

(the desired state among workers) consists of sitting around

and doing nothing. Of course people have interests and would

like to be active, but except for the lucky few, such interests

from the viewpoint of the market must be considered

"hobbies." The job of the market is to get people to perform

services that are "demanded," with due regard for the wage

differentials required by different amounts of talent, skill and

training, as well as compensating differentials required by the

varying attractiveness of jobs.

In the eighteenth century, a simpler and more extreme

version of this theory held that workers worked only to avoid

starvation, so that the utility attaching to increments of

income above the subsistence level was zero. In this case, no

increase however large in wages could ever induce more work

12

BCAS. All rights reserved. For non-commercial use only. www.bcasnet.org

from a laborer. The more he is paid, the less work he need