Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Current Concept of Eclampsia

Uploaded by

drheayOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Current Concept of Eclampsia

Uploaded by

drheayCopyright:

Available Formats

Reviews

A Current Concept of Eclampsia

HADASSAH LIPSTEIN, MD, CHRISTOPHER C. LEE, MD, AND ROBERT S. CRUPI, MD

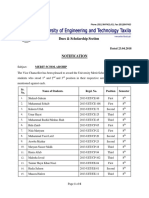

Eclampsia is dened by the occurrence of seizures resulting from hypertensive encephalopathy on the background of preeclampsia. The development of hypertension during pregnancy, a serious and potentially fatal condition, is a leading cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and death in the United States.1-3 It is a disease with preventable complications. The pathophysiology of hypertension during pregnancy is unclear, but there is consensus that aggressive treatment is warranted to prevent complications to both fetus and mother. A current concept of pathophysiological character, diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia is discussed. (Am J Emerg Med 2003;21:223-226. 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.)

The following 5 types of hypertensive disorders can complicate pregnancy4-5: (1) gestational hypertension, also called pregnancy-induced or transient hypertension; (2) preeclampsia; (3) eclampsia; (4) preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension; and (5) chronic hypertension. According to the protocol established by the Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecology, a diagnosis of gestational hypertension is made when there is a sustained blood pressure 140/90 mm Hg, not associated with proteinuria, that is diagnosed for the rst time after 20 weeks of pregnancy and returns to normal less than 12 weeks postpartum.4,6,7 This diagnosis is further divided into mild to moderate and severe disease. There does not seem to be an increased maternal or fetal risk with mild to moderate hypertension, which is a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) between 90 and 109 mm Hg.8 Although severe pregnancyinduced hypertension, dened as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 170 or a DBP of 110, is dangerous and must be treated, there is an even greater risk of perinatal and maternal mortality and morbidity from preeclampsia and eclampsia.4 Sometimes called toxemia of pregnancy, they are among the leading causes of maternal complications and death worldwide.9 Preeclampsia is characterized by hypertension diagnosed after 20 weeks gestation plus proteinuria. In severe cases,

From the Department of Emergency Medicine, Flushing Hospital Medical Center, Flushing, NY. Manuscript received and accepted July 24, 2002. Address reprint requests to Christopher C. Lee, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Flushing Hospital Medical Center, 45th Ave. at Parsons Blvd., Flushing, NY 11355. E-mail: Flushingerdoc@aol.com Key Words: Eclampsia, pregnancy, hypertension, seizure. 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 0735-6757/03/2103-0014$30.00/0 doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(02)42241-3

the DBP is 110 mm Hg, there is a persistent proteinuria of 2 or more, and any of the following can be present: headaches, visual disturbances, upper abdominal pain, oliguria, increased serum creatinine, thrombocytopenia, increased liver enzymes, fetal growth retardation, and pulmonary edema. A pregnant woman who presents with these symptoms must be treated immediately because this can signify the imminent development of eclampsia. Eclampsia is the new onset of seizures before, during, or after labor, which is not attributable to other causes, in a woman with preeclampsia. Seizures in a pregnant woman who had not been previously diagnosed with preeclampsia must be accompanied by 2 of the following within 24 hours of presentation to be considered eclamptic: hypertension, proteinuria, thrombocytopenia, or increased aspartate aminotransferase.10 The onset of convulsions can be sudden in up to 16% of the cases.11 Among women with a previously diagnosed hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, those with severe preeclampsia pose the highest risk of developing into eclampsia.11 For years, investigators have attempted to gain a better understanding of eclampsia, but still it remains a mystery. An exact etiology has not been discovered.7 It has been theorized that eclampsia is the natural linear evolvement from preeclampsia. Eclampsia, however, has manifested without warning or signs of preeclampsia. It has been reported that up to 38% of eclamptic seizures can occur without previous signs and symptoms.10 In a retrospective analysis by Katz et al.,12 eclampsia was not found to be a progression from preeclampsia. Questions as to the predictability of the seizures have been raised.8 Although current practice is to give prophylactic treatment to patients who present with preeclampsia, up to 40% of seizures occur before hospitalization.13 An additional 16% occur more than 48 hours postpartum.13 Only half of all eclamptic seizures can be expected to benet form seizure prophylaxis. Because eclampsia remains a potentially life-threatening, emergent condition of pregnancy, it would benet all ED physicians to possess a good understanding of the disease. In this review, we discuss the epidemiology, pathophysiology, signs and symptoms, complications, and prevention and management of eclampsia in an attempt to familiarize the ED doctor with this dangerous but treatable condition. EPIDEMIOLOGY Seven percent to 15% of pregnancies are complicated by hypertensive disorders.6 Preeclampsia affects up to 7% of pregnancies and 1% of these women develop eclampsia.13 The incidence of eclampsia in the Western world is approx223

224

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE s Volume 21, Number 3 s May 2003

imately 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 3,000 deliveries and can be higher in developing countries.14-17 In referral centers the rate reaches as high as 1 in 200 deliveries. Of the 500,000 pregnancy-related deaths per annum, as many as 50,000 result from eclampsia.7,18 Approximately 1 in 50 women experiencing eclamptic seizures will die annually from complications.10 That gure can reach as high as 14% in the nonindustrialized world.10 It has been reported that eclampsia results in stillbirths or neonatal demise at a rate of 1 in 14.10 Although the incidence of preeclampsia has not changed signicantly over the past 6 decades, the rate of major complications from the disease has been on a marked decline.15 DEFINITIONS, SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS Like previously mentioned, preeclampsia is dened as a blood pressure 140/90 mm Hg which is associated with proteinuria and pathologic edema. Proteinuria is characterized by urine protein of 300 mg or more in a 24-hour collection specimen or persistent 1 (30 mg/dL) urine dipstick in random samples. The development of neurologic symptoms, including: headache, visual disturbances, epigastric pain, oliguria, and depression of consciousness, are a portent of incipient convulsions. Other signs that aid in the diagnosis of severe disease are thrombocytopenia, increased liver enzymes, intrauterine growth restriction, and pulmonary edema. Eclampsia is the new onset of seizures in a pregnant woman that cannot be explained by any preexisting cerebral condition. Lopez-Llera16 created a classication system according to the onset of the seizures. Antepartum eclampsia refers to the onset of convulsions before the start of labor. It is considered early if it occurs before 28 weeks gestation. Convulsions that occur during labor are called intrapartum eclampsia, and postpartum eclampsia is the occurrence of seizures within 7 days of delivery of the fetus and placenta. Intercurrent eclampsia, which is the least clinically signicant of all but should not be ignored, refers to convulsions that appear antepartum but subside with enough clinical improvement to allow the continuation of the pregnancy for longer than 1 week. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY A number of theories have been hypothesized as to the etiology of toxemia, including placental abnormalities, immunologic disturbances, endothelial cell compromise, genetic factors, and dietary inuences.19 None of the investigations, as of yet, have resulted in concrete evidence, thus the etiology remains unclear.7 There is a widespread belief that reduced uteroplacental perfusion is the central pathophysiological process involved in the development of preeclampsia.7 Odent,20 in his review, points out that an association between preeclampsia and large-for-gestational-age infants, in addition to small-for-gestational-age infants, places doubt in that theory. He proposes that preeclampsia could be the result of maternal-fetal conict. EPA (a long chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid) is required by the developing fetal brain. The theory is that the fetus need for the metabolites of EPA override the maternal need. A decrease in maternal EPA in preeclamptic and eclamptic

women as compared with their normotensive counterparts appears to play a role in the development of this condition. Other studies tried to show a genetic basis for the disease. A family history of preeclampsia is associated with a fourfold increased risk of the disease in primigravidas.21 Chelsey et al. showed that daughters of mothers who had eclampsia were at greater risk of developing the disease than daughters-in-law.7 Treloar et al.21 conducted studies to prove concordance among monozygotic twin pairs. Their data did not conclusively prove clear-cut maternal genetic inuence; however, the existence of maternal genes that cause a susceptibility to developing preeclampsia could not be ruled out.22 Decreased organ perfusion secondary to vasospasm and endothelial cell damage is also thought to play an etiologic role in the pathogenesis of the disease.4 Direct observation of vasospasm of the small blood vessels in nail beds, ocular fundi, and bulbar conjunctivae supports this theory. Histologic changes seen in blood vessel walls corroborate the concept of endothelial cell damage as an etiologic factor. An investigation into the clinical parameters associated with the development of brain edema of hypertensive encephalopathy in toxemic patients conducted by Schwartz et al.23 showed an association between severe disease and abnormal red blood cell morphology and increased lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. These ndings indicate the presence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, which suggests that endothelial damage does indeed play a causative role in the pathogenesis of eclampsia.24-26 Other possible etiologic factors responsible for eclamptic convulsions include cerebral vasospasm, hemorrhage, or edema, metabolic, hypertensive encephalopathy.11 COMPLICATIONS Women who develop preeclampsia or eclampsia are at increased risk for a number of complications. Abruptio placentae is the most common complication encountered,11 and there is a higher incidence among women with antepartum eclampsia.17 A syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and a low platelet count, known as the HELLP syndrome, can complicate up to 10% of eclamptic cases.11,27 Mortality resulting from the HELLP syndrome ranges from 2% to 24% of cases.1 This too has a higher incidence in antepartum eclampsia.17 Other adverse problems that can arise as a result of eclampsia include acute renal failure, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular complications, as well as maternal and fetal death.1 Cerebral hemorrhage, the most serious complication, has been shown to be the fatal event in 50% to 65% of the cases.1,11 Sudden increases in severe diastolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg heighten the risk of death and developing lethal complications such as hypertensive encephalopathy, ventricular arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.9 Pulmonary edema and aspiration pneumonia, which are usually iatrogenic, can develop as a result of uid overload and poor management.28 Munro10 reported a rate of 23% of women requiring ventilation resulting from eclampsia or its complications. Retinal detachment can also occur after an eclamptic seizure. Transient neurologic decits and transient cortical blindness, seen more often as a result of postpartum eclampsia,17 occur in 3.1% and 2.3% of eclamptic women, respectively. Every

LIPSTEIN ET AL s A CURRENT CONCEPT OF ECLAMPSIA

225

effort must be taken to prevent the development of eclampsia to avoid these deadly repercussions. PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT Because the etiology of eclampsia is not fully known, we must view this disease from a different angle to prevent it from occurring. Prima gravidity, lack of prenatal care, urinary tract infections, family history, diabetes mellitus, multiple gestation, extremes of age, obesity, black ethnicity, preexisting hypertension, vascular renal disease, prolonged labor, and hydatidiform moles can predispose a pregnant woman to eclampsia.7,13 Awareness of these factors can aid in identifying those at greatest risk for developing this disease. Although it is a life-threatening condition, eclampsia can be prevented with proper antenatal care.29 Early detection is the key to successful management.3 Regular visits throughout the pregnancy with an increase in the frequency of visits in the third trimester has been shown to be effective in limiting the morbidity and mortality from eclampsia.1 Preventive therapy or early recognition and care are associated with improved maternal and fetal outcomes as well.11 The best treatment for preeclampsia and eclampsia is delivery. If delivery is not possible or warranted, then management of the patient should include hospitalization, close observation, and prophylaxis against convulsions until termination can be performed. In-hospital care should include daily evaluations with particular attention to clinical ndings, daily weigh-ins, blood pressure readings every 4 hours, and prophylactic anticonvulsive therapy.4 Prophylactic therapy for preeclampsia follows the same regimen as treatment for eclampsia. The accepted protocol in the United States, developed by Zuspan and modied by Sibai and his colleagues, is a 6-g loading dose of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) administered intravenously followed by the continuous infusion of 2 g per hour.13 Special attention must be paid to the development of harmful side effects, such as overdose which can lead to death, excessive bleeding, inhibited spontaneous motility, increased blood loss, respiratory depression, and pulmonary edema. Many trials have been done to determine the efcacy of the drug in preventing and controlling eclamptic seizures. There is strong support for the use of MgSO4 for seizure prophylaxis in severe preeclampsia.13,30 Limited evidence exists for the routine use of MgSO4 for prophylaxis against convulsions in mild gestational hypertension and mild preeclampsia. The Collaborative Eclampsia Trial Group proved the superiority of MgSO4 for reducing recurrence of seizures.14 In another study, MgSO4 was shown to be superior to phenytoin and diazepam for the prevention and treatment of eclamptic convulsions.7 Once eclampsia has occurred, medical management with MgSO4 to stabilize the mother and prevent further seizures is necessary. The therapy is continued for at least 24 hours postpartum. Oxygen supplementation by facemask is sufcient to treat hypoxia caused by the convulsions. If the airway is compromised, then intubation is required. High blood pressure should be managed with a 5-mg loading dose of intravenous hydralazine, followed every 20 minutes with 5 to 10 mg until a maximum of 80 mg has been reached or the desired blood pressure has been achieved. Once the mother is stabilized, the fetus condition must be assessed. Fetal heart rate should be monitored and

a biophysical prole should be performed. Only after the mother is stabilized can a delivery be attempted. The ultimate goal of the treating physician is the termination of the pregnancy with the least amount of trauma to the mother and baby, the birth of an infant who will eventually thrive, and complete restoration of maternal health.4 If a patient has had a seizure and the diagnosis of eclampsia is made, several anticonvulsant regimens can be used. The Eclampsia Trial Collaborative Group study included 1,687 women with eclampsia who were randomly allocated anticonvulsant regimens. The primary outcome measures were recurrence of convulsions and maternal deaths. The 453 women were randomized to magnesium sulfate compared with 452 given diazepam. Another 388 eclamptic women were randomized to magnesium sulfate and compared with 387 women given phenytoin. The women allocated to magnesium sulfate therapy had a 50% reduction in incidence of recurrent seizures than those given diazepam (60 v 126 seizures, respectively). Maternal and perinatal morbidity were not different between these 2 groups. In a second comparison, the women randomized to receive magnesium sulfate compared with phenytoin had a 67% reduced incidence of recurrent convulsions. Maternal mortality was lower in the magnesium group compared with the phenytoin group (2.6% v 5.2%). The Collaborative Group concluded that there is compelling evidence in favor of magnesium sulfate rather than diazepam or phenytoin for the treatment of eclampsia. If barbiturates are used, the choice is amobarbital at a dose of 250 mg intravenously given over 3 to 5 minutes. DISCUSSION Eclampsia is a potentially lethal but treatable hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Review of current literature supports the use of MgSO4 for seizure prophylaxis in severely preeclamptic women. The benet of prophylactic therapy for mild disease, however, is not clearly documented. It has been reported that over the last few decades there has been a reduction in the incidence of eclampsia.15 Better management and regular antenatal care are partly responsible for this trend. Still, eclampsia is responsible for as many as 50,000 pregnancy-related deaths per year. Most investigators have noted that the majority of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality results from out-of-hospital seizures.12 Currently, there are no reliable, valid, or economic methods of screening for eclampsia.4 Further studies are required to gain additional knowledge and better understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease. In addition, investigations into uncovering reliable predictors of eclampsia are warranted so we can develop tests that will help detect eclampsia and prevent those seizures that are at present unpredictable. Until that time, familiarity with emergency management of toxemia of pregnancy and its complications is the best means of keeping the trend of morbidity and mortality from eclampsia on a downward slope. REFERENCES

1. Mackay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK: Pregnancy related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:533538

226

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE s Volume 21, Number 3 s May 2003

2. Witlin AG, Saade GR, Mattar F, Sibai BM: Risk factors for abruptio placentae and eclampsia: Analysis of 445 consecutively managed women with severe preeclampsia and eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:1322-1329 3. Brady WJ, De Behnke DJ, Carter CT: Postpartum toxemia: Hypertension, edema, proteinuria and unresponsiveness in an unknown female. J Emerg Med 1995;13:643-648 4. Cunningham FG, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, et al: Williams obstetrics. 21st ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2001 5. Chesley LC: Recognition of the long-term sequelae of eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:249-250 6. Lenfant C: National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group report on high blood pressure in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:1689 7. Ramin KD: The prevention and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am 1999;26:489-503 8. Adis International Ltd: Consider both the unborn child and mother when treating hypertension in pregnancy. Drug Ther Perspect 2001;17:11-15 9. Repke JT, Robinson JN: The prevention and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1998;62:1-9 10. Munro PT: Management of eclampsia in the accident and emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med 2000;17:7-11 11. Usta IM, Sibai BM: Emergent management of puerperal eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am 1995;22:315-335 12. Katz V, Farmer R, Kuller JA: Preeclampsia into eclampsia: Toward a new paradigm. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:13891396 13. Witlin AG, Sibai BM: Magnesium sulfate therapy in preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gyencol 1998;92:883-889 14. Duley L, et al: Which anticonvulsant for women with eclampsia? Evidence from the Colllaborative Eclampsia Trial. Lancet 1995; 345:1455-1463 15. Leitch CR, Cameron AD, Walker JJ: The changing pattern of eclampsia over a 60 year period. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104: 917-922 16. Lopez-Llera M: Main clinical subtypes of eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:4-9

17. Mattar F, Sibai BM. EclampsiaRisk factors for maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;182:307-312 18. Chien PFW, Khan KS, Arnott N: Magnesium sulphate in the treatment of eclampsia and preeclampsia: An overview of the evidence from randomised trials. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103: 1085-1091 19. Maine D: Role of nutrition in the prevention of toxemia. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:298S-300S 20. Odent M: Hypothesis: Preeclampsia as a maternal-fetal conict. Med Gen Med J 2001;3:x-x 21. Treolar SA, Cooper DW, Brennecke MB, et al: An Australian twin study of the genetic basis of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:374-381 22. Khatun S, Kanayama N, Belayet H, et al: Increased concentrations of plasma neuropeptide Y in patients with eclampsia and preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:896-900 23. Schwartz RB, Feske SK, Polak JF, et al: Preeclampsiaeclampsia: Clinical and neuroradiographic correlates ad insights into the pathogenesis of hypertensive encephalopathy. Radiology 2000;217:371-376 24. Redman CW, Sergent IL: The pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2001;29:518-522 25. Sawhney H, Aggarwal N, Biswas R, et al: Maternal mortality associated with eclampsia and severe preeclampsia of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2000;26:351-356 26. Sungani FC, Malata A, Masanjika R: Preeclampsia/eclampsia: A literature review. Cent Afr J Med 1998;44:261-263 27. Haddad B, Barton JR, Livingston JC, Chahine R, Sibai BM: Risk factors for adverse maternal outcomes among women with HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:444-448 28. Gilbert WM, Towner DR, Field NT, Anthony J: The safety and utility of pulmonary artery catheterization in severe preeclampsia and eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:1397-1403 29. Mahran M: Eclampsia: A leading cause of maternal mortality. J Perinat Med 2001;19:235-240 30. Hall DR, Odendaal HJ, Smith M: Is the prophylactic administration of magnesium sulphate in women with preeclampsia indicated prior to labor. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;107:903-908

You might also like

- DSA Interview QuestionsDocument1 pageDSA Interview QuestionsPennNo ratings yet

- Volvo FM/FH with Volvo Compact Retarder VR 3250 Technical DataDocument2 pagesVolvo FM/FH with Volvo Compact Retarder VR 3250 Technical Dataaquilescachoyo50% (2)

- English: Quarter 1 - Module 1Document16 pagesEnglish: Quarter 1 - Module 1Ryze100% (1)

- PEBjournalDocument8 pagesPEBjournalLisa Linggi'AlloNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Pre-Eclampsia, Diagnosis, Risk Factors, Complications, Management, AnesthesiaDocument14 pagesKeywords: Pre-Eclampsia, Diagnosis, Risk Factors, Complications, Management, AnesthesiaAyu W. AnggreniNo ratings yet

- New Aspects in The Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia: Clinical ScienceDocument27 pagesNew Aspects in The Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia: Clinical Sciencenaumee100% (2)

- Pre-Eclampsia: A Lifelong Disorder: 1974 (CWLTH) Both Need Further ExaminationDocument3 pagesPre-Eclampsia: A Lifelong Disorder: 1974 (CWLTH) Both Need Further ExaminationCarloxs1No ratings yet

- Preeclampsia, A New Perspective in 2011: M S S M. S - SDocument10 pagesPreeclampsia, A New Perspective in 2011: M S S M. S - SharyatikennitaNo ratings yet

- COPO - Trans CPG HPNDocument14 pagesCOPO - Trans CPG HPNNico Angelo CopoNo ratings yet

- Pre-eclampsia Guide: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocument12 pagesPre-eclampsia Guide: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentJohn Mark PocsidioNo ratings yet

- PreeclampsiaDocument11 pagesPreeclampsiaArtyom GranovskiyNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: American Journal of Obstetrics and GynecologyDocument55 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: American Journal of Obstetrics and GynecologyManuel MagañaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension and Management: Preeclampsia: Pathophysiology and The Maternal-Fetal RiskDocument5 pagesHypertension and Management: Preeclampsia: Pathophysiology and The Maternal-Fetal RiskMarest AskynaNo ratings yet

- PreeclampsiaDocument14 pagesPreeclampsiaHenny NovitasariNo ratings yet

- Pre EclampsiaDocument17 pagesPre Eclampsiachristeenangela0% (1)

- Women's Health ArticleDocument15 pagesWomen's Health ArticleYuli HdyNo ratings yet

- BR Med Bull 2003 Duley 161 76Document16 pagesBR Med Bull 2003 Duley 161 76rachel0301No ratings yet

- Preeklampsia - Searching CauseDocument2 pagesPreeklampsia - Searching CausevannyanoyNo ratings yet

- Searching for genetic clues to causes of pre-eclampsiaDocument16 pagesSearching for genetic clues to causes of pre-eclampsiaBian DaraNo ratings yet

- Preeclampsia Induced Liver Disease and HELLP SyndromeDocument20 pagesPreeclampsia Induced Liver Disease and HELLP SyndromeanggiehardiyantiNo ratings yet

- Alh 2220 Preeclampsia Research PaperDocument9 pagesAlh 2220 Preeclampsia Research Paperapi-431367905No ratings yet

- EclampsiaDocument8 pagesEclampsiaAtef Kamel SalamaNo ratings yet

- Placental Origins of PEDocument7 pagesPlacental Origins of PENi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- VHRM 7 467Document9 pagesVHRM 7 467Giri Endaristi TariganNo ratings yet

- 10.1038@s41581 019 0119 6 PDFDocument15 pages10.1038@s41581 019 0119 6 PDFAndreas NatanNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading Preeclampsia: Pathophysiology and The Maternal-Fetal RiskDocument23 pagesJournal Reading Preeclampsia: Pathophysiology and The Maternal-Fetal RiskAulannisaHandayaniNo ratings yet

- Patofisiología de La Pre-EclampsiaDocument36 pagesPatofisiología de La Pre-EclampsiaAngie DíazNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: Overview and Current RecommendationsDocument12 pagesHypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: Overview and Current RecommendationsPamela LacentvaneseNo ratings yet

- Huppert Z 2008Document7 pagesHuppert Z 2008Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Eclampsia as a Leading Cause of Maternal Mortality in NigeriaDocument26 pagesEclampsia as a Leading Cause of Maternal Mortality in NigeriaHadiza Adamu AuduNo ratings yet

- Gestational Hypertension Is Defined As New-Onset Blood PressureDocument9 pagesGestational Hypertension Is Defined As New-Onset Blood PressureMohamad Nur M. AliNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Advances in The Pathophysiology of Pre-Eclampsia and Related Podocyte InjuryDocument22 pagesHHS Public Access: Advances in The Pathophysiology of Pre-Eclampsia and Related Podocyte InjuryRenov BaligeNo ratings yet

- (PIH) CASE PRESENTATION (Group11)Document41 pages(PIH) CASE PRESENTATION (Group11)Kaye Drexcel SequilloNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Preeclampsia and Stroke: Risks During and After PregnancyDocument10 pagesReview Article: Preeclampsia and Stroke: Risks During and After Pregnancyriena456No ratings yet

- Update in The Management of Patients With Preeclampsia 2017 PDFDocument12 pagesUpdate in The Management of Patients With Preeclampsia 2017 PDFfujimeister100% (1)

- Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy: Clinical PracticeDocument8 pagesChronic Hypertension in Pregnancy: Clinical PracticecornelNo ratings yet

- البحث aziz alhaidariDocument51 pagesالبحث aziz alhaidariabdulaziz saif ali mansoorNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 775233Document16 pagesNi Hms 775233Mikhail NurhariNo ratings yet

- Other Symptoms: Pre-Eclampsia or Preeclampsia Is ADocument2 pagesOther Symptoms: Pre-Eclampsia or Preeclampsia Is ADezca NinditaNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Pre-Eclampsia Part 1: Current Understanding of Its PathophysiologyDocument15 pagesReviews: Pre-Eclampsia Part 1: Current Understanding of Its PathophysiologyKartika LuthfianaNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Epidemiology of Preeclampsia: Impact of ObesityDocument14 pagesNIH Public Access: Epidemiology of Preeclampsia: Impact of ObesityHani FatimahNo ratings yet

- Vitamin E in Preeclampsia: Lucilla Poston, Maarten Raijmakers, and Frank KellyDocument7 pagesVitamin E in Preeclampsia: Lucilla Poston, Maarten Raijmakers, and Frank KellyGheavita Chandra DewiNo ratings yet

- Preeclampsia (Toxemia of Pregnancy) : Background: Preeclampsia Is A Disorder Associated With PregnancyDocument12 pagesPreeclampsia (Toxemia of Pregnancy) : Background: Preeclampsia Is A Disorder Associated With PregnancyRita AryantiNo ratings yet

- Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy: Clinical PracticeDocument8 pagesChronic Hypertension in Pregnancy: Clinical PracticeemmoyNo ratings yet

- Risk factors for preeclampsia عبدالسلامDocument5 pagesRisk factors for preeclampsia عبدالسلامmqbljbr529No ratings yet

- Alteraciones Hematológicas en Recién Nacidos Pretérmino de Madres Con Enfermedad Mexico 2022Document6 pagesAlteraciones Hematológicas en Recién Nacidos Pretérmino de Madres Con Enfermedad Mexico 2022ana leonor hancco mamaniNo ratings yet

- Hypertension PregnancyDocument45 pagesHypertension PregnancyMohammed IbraheemNo ratings yet

- Do Not Forget About HELLP!: Reminder of Important Clinical LessonDocument2 pagesDo Not Forget About HELLP!: Reminder of Important Clinical Lessonocpc2011No ratings yet

- Severe PreeclampsiaDocument84 pagesSevere PreeclampsiaJm Bernardo50% (2)

- Dines 2020 ACKD Hypertensive Disorders of PregnancyDocument9 pagesDines 2020 ACKD Hypertensive Disorders of PregnancyBCR ABLNo ratings yet

- Presentation Pre EclampsiaDocument25 pagesPresentation Pre EclampsiaChidube UkachukwuNo ratings yet

- PreeclamsiaDocument22 pagesPreeclamsiaJosé DomínguezNo ratings yet

- Bahan Bacaan PreeklampsiaDocument11 pagesBahan Bacaan PreeklampsiaMegan LewisNo ratings yet

- Preeclampsia An Obstetrician's Perspective - XackdDocument10 pagesPreeclampsia An Obstetrician's Perspective - XackdLiz Valentina Jordan MoyaNo ratings yet

- CP Preeclampsia RevisedDocument32 pagesCP Preeclampsia RevisedTessa Grace PugonNo ratings yet

- PIIS0002937820311285Document17 pagesPIIS0002937820311285Jose Francisco Zamora ScottNo ratings yet

- Kahn 1998Document3 pagesKahn 1998Sheila Regina TizaNo ratings yet

- Pre EclampsiaDocument13 pagesPre EclampsiaEniamrahs DnalonNo ratings yet

- Hypertension in Pregnancy: Diagnosis and ManagementDocument10 pagesHypertension in Pregnancy: Diagnosis and ManagementDinorah MarcelaNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Eclampsia Clinical Study (IJSRDocument3 pagesPostpartum Eclampsia Clinical Study (IJSRSulabh ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Pre-eclampsia Seminar Reviews Diagnosis, Risk Factors and PathogenesisDocument15 pagesPre-eclampsia Seminar Reviews Diagnosis, Risk Factors and Pathogenesisannoying_little_prankster9134No ratings yet

- Hypertension in PregnancyDocument137 pagesHypertension in PregnancyFedlu SirajNo ratings yet

- Pre-eclampsia, (Pregnancy with Hypertension And Proteinuria) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandPre-eclampsia, (Pregnancy with Hypertension And Proteinuria) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Neuropathies (2013)Document13 pagesNutritional Neuropathies (2013)drheayNo ratings yet

- Cervical Lymph Node Evaluation and Diagnosis (2012)Document21 pagesCervical Lymph Node Evaluation and Diagnosis (2012)drheayNo ratings yet

- Current Practice and Future Directions in The Prevention and Acute Management of Migraine (2010) PDFDocument14 pagesCurrent Practice and Future Directions in The Prevention and Acute Management of Migraine (2010) PDFdrheayNo ratings yet

- Crisis in Sickle Cell DiseaseDocument12 pagesCrisis in Sickle Cell DiseasedrheayNo ratings yet

- The Cholangiopathies (2015)Document10 pagesThe Cholangiopathies (2015)drheayNo ratings yet

- Congenital Heart Disease (2011)Document17 pagesCongenital Heart Disease (2011)drheay100% (1)

- Behcet's Syndrome (2013)Document17 pagesBehcet's Syndrome (2013)drheayNo ratings yet

- Drug-Induced Liver Injury (2014) PDFDocument12 pagesDrug-Induced Liver Injury (2014) PDFdrheayNo ratings yet

- Behcet's Syndrome (2013)Document17 pagesBehcet's Syndrome (2013)drheayNo ratings yet

- Coma in The Pregnant Patient (2011)Document22 pagesComa in The Pregnant Patient (2011)drheayNo ratings yet

- Influenza (2013) PDFDocument25 pagesInfluenza (2013) PDFdrheayNo ratings yet

- Emerging Therapies in Hepatitis C. Dawn of The Era of The Direct Acting Antivirals (2011)Document14 pagesEmerging Therapies in Hepatitis C. Dawn of The Era of The Direct Acting Antivirals (2011)drheayNo ratings yet

- Ocular Manifestations of ANCA Associated Vasculitis (2010)Document14 pagesOcular Manifestations of ANCA Associated Vasculitis (2010)drheayNo ratings yet

- Venomous Bites Stings and PoisoningDocument17 pagesVenomous Bites Stings and Poisoningdrheay100% (1)

- Abdominal Pain in Special Populations (2011)Document10 pagesAbdominal Pain in Special Populations (2011)drheayNo ratings yet

- Diarrhea from Carbohydrate MalabsorptionDocument17 pagesDiarrhea from Carbohydrate MalabsorptiondrheayNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Review of The Adverse Effects of Systemic Corticosteroids (2010) PDFDocument16 pagesA Comprehensive Review of The Adverse Effects of Systemic Corticosteroids (2010) PDFdrheay100% (1)

- Metabolic Myopathies. Clinical Features and Diagnostic Approach (2011)Document17 pagesMetabolic Myopathies. Clinical Features and Diagnostic Approach (2011)drheayNo ratings yet

- Clostridium Difficile in The ICU (2011)Document11 pagesClostridium Difficile in The ICU (2011)drheayNo ratings yet

- Renal and Urologic Emergencies in The HIV Infected Patients (2010) PDFDocument12 pagesRenal and Urologic Emergencies in The HIV Infected Patients (2010) PDFdrheayNo ratings yet

- Renal Sympathetic Denervation For Resistant Hypertension Treatment. Current Perspectives (2013)Document8 pagesRenal Sympathetic Denervation For Resistant Hypertension Treatment. Current Perspectives (2013)drheayNo ratings yet

- Calcium Metabolism and Correcting Calcium Deficiencies (2012)Document30 pagesCalcium Metabolism and Correcting Calcium Deficiencies (2012)drheayNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Review of The Adverse Effects of Systemic Corticosteroids (2010) PDFDocument16 pagesA Comprehensive Review of The Adverse Effects of Systemic Corticosteroids (2010) PDFdrheay100% (1)

- Infectious Complications of Dyalisis Access Devices (2012)Document15 pagesInfectious Complications of Dyalisis Access Devices (2012)drheayNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Implications of Hypoglycemia in Diabetes Mellitus (2015)Document7 pagesCardiovascular Implications of Hypoglycemia in Diabetes Mellitus (2015)drheayNo ratings yet

- Physiology of Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Therapy in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes (2012)Document15 pagesPhysiology of Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Therapy in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes (2012)drheayNo ratings yet

- Adrenal Disorders in Rheumatology (2010)Document12 pagesAdrenal Disorders in Rheumatology (2010)drheayNo ratings yet

- Cocaine IntoxicationDocument10 pagesCocaine IntoxicationdrheayNo ratings yet

- Envenom AtionsDocument30 pagesEnvenom AtionsdrheayNo ratings yet

- Update On Sleep and Psychiatric DisordersDocument12 pagesUpdate On Sleep and Psychiatric DisordersdrheayNo ratings yet

- Intro to Financial Management Chapter 1 SummaryDocument11 pagesIntro to Financial Management Chapter 1 SummaryweeeeeshNo ratings yet

- ! Sco Global Impex 25.06.20Document7 pages! Sco Global Impex 25.06.20Houssam Eddine MimouneNo ratings yet

- Spelling Errors Worksheet 4 - EditableDocument2 pagesSpelling Errors Worksheet 4 - EditableSGillespieNo ratings yet

- Myrrh PDFDocument25 pagesMyrrh PDFukilabosNo ratings yet

- Kristine Karen DavilaDocument3 pagesKristine Karen DavilaMark anthony GironellaNo ratings yet

- M2M RF - RHNDocument3 pagesM2M RF - RHNNur Nadia Syamira Bt SaaidiNo ratings yet

- Towards Emotion Independent Languageidentification System: by Priyam Jain, Krishna Gurugubelli, Anil Kumar VuppalaDocument6 pagesTowards Emotion Independent Languageidentification System: by Priyam Jain, Krishna Gurugubelli, Anil Kumar VuppalaSamay PatelNo ratings yet

- The Free Little Book of Tea and CoffeeDocument83 pagesThe Free Little Book of Tea and CoffeeNgopi YukNo ratings yet

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDocument6 pagesDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDNo ratings yet

- 12 Smart Micro-Habits To Increase Your Daily Productivity by Jari Roomer Better Advice Oct, 2021 MediumDocument9 pages12 Smart Micro-Habits To Increase Your Daily Productivity by Jari Roomer Better Advice Oct, 2021 MediumRaja KhanNo ratings yet

- Absenteeism: It'S Effect On The Academic Performance On The Selected Shs Students Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesAbsenteeism: It'S Effect On The Academic Performance On The Selected Shs Students Literature Reviewapi-349927558No ratings yet

- Coursebook 1Document84 pagesCoursebook 1houetofirmin2021No ratings yet

- Transpetro V 5 PDFDocument135 pagesTranspetro V 5 PDFadityamduttaNo ratings yet

- SHS Track and Strand - FinalDocument36 pagesSHS Track and Strand - FinalYuki BombitaNo ratings yet

- Transportation ProblemDocument12 pagesTransportation ProblemSourav SahaNo ratings yet

- Tomato & Tomato Products ManufacturingDocument49 pagesTomato & Tomato Products ManufacturingAjjay Kumar Gupta100% (1)

- Plo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentDocument22 pagesPlo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentkrystelNo ratings yet

- Beyond Digital Mini BookDocument35 pagesBeyond Digital Mini BookAlexandre Augusto MosquimNo ratings yet

- Decision Support System for Online ScholarshipDocument3 pagesDecision Support System for Online ScholarshipRONALD RIVERANo ratings yet

- Understanding Abdominal TraumaDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Abdominal TraumaArmin NiebresNo ratings yet

- Present Tense Simple (Exercises) : Do They Phone Their Friends?Document6 pagesPresent Tense Simple (Exercises) : Do They Phone Their Friends?Daniela DandeaNo ratings yet

- PAASCU Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesPAASCU Lesson PlanAnonymous On831wJKlsNo ratings yet

- 01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsDocument11 pages01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsEnrique BlancoNo ratings yet

- GPAODocument2 pagesGPAOZakariaChardoudiNo ratings yet

- 2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanDocument10 pages2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Senarai Syarikat Berdaftar MidesDocument6 pagesSenarai Syarikat Berdaftar Midesmohd zulhazreen bin mohd nasirNo ratings yet

- God Love Value CoreDocument11 pagesGod Love Value CoreligayaNo ratings yet