Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Oral Habits As Risk Factors For Anterior Open Bite in The Deciduous and Mixed Dentition - Cross Sectional Study

Uploaded by

APinhaoFerreiraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oral Habits As Risk Factors For Anterior Open Bite in The Deciduous and Mixed Dentition - Cross Sectional Study

Uploaded by

APinhaoFerreiraCopyright:

Available Formats

V. Urzal*, A.C. Braga**, A.P.

Ferreira

Department of Orthodontics and Oral Facial Genetics, Faculty of Dentistry, Porto University, Portugal *PhD Student **Department of Production and Systems, School of Engineering, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal e-mail: vandaurzal@gmail.com

Introduction

Despite the genetic pattern of facial growth that has to be considered [Nielsen, 1991], AOB is the occlusal anomaly most commonly associated with dysfunctional habits [Nielsen, 1991; Stahl et al., 2007; Stahl and Grabowski, 2003]. However, the scientic literature is contradictory on which OH lead to AOB [Cozza et al., 2005], and Proft admits that only 5% of the exact causes of malocclusion are known [Stahl et al., 2007]. OH interfere with normal development and function of the orofacial musculature [Gallardo and Cencillo, 2005]. For instance, sucking an object leads to extension of the head and neck and simultaneously increases the oral opening with mandibular rotation, causing a lower insertion of the masseter over the gonial angle and the horizontal branch of the mandible. Its bres acquire a different orientation leading to facial hyperdivergency [Landouzy et al., 2009]. However, children with a high angle frequently have airway problems, which involve a mandibular posterior rotation [Linder-Aronson, 1970, 1975] and a weaker masticatory musculature [Mller, 1966; Ingervall, 1974] allowing more freedom for molar eruption [Nielsen, 1991]. The query is in which cases a genetic pattern leads to a habit or/and a habit leads to a permanent malocclusion. The multifactorial cause of AOB can be attributed to a combination of skeletal, dental and soft-tissues effects [Doshi and Bhad, 2011], namely the discrepancy between the rate of condilar growth and the maxillary sutures, the dysfunction of the lips and tongue as well as the dentoalveolar development [Nielsen, 1991]. Nevertheless, the change in the soft tissues pressure, when in the rest position, is the most important factor due to its continuous effect [Stahl et al., 2007]. A persistent period of oral habits could have implications in the genesis of this malocclusion during growth [Gis et al., 2011; Giuntini et al., 2008], being the functional stress factors among the primary causes of disturbed development of dentition [Stahl and Grabowski, 2003]. The reducing prevalence of AOB from the deciduous to the mixed dentition (16.9% to 11.3%) [Urzal et al., 2012] suggests that this anomaly is often of dentoalveolar origin [Doshi and Bhad, 2011; Tschill et al., 1997] and is associated with orofacial dysfunctions [Stahl and Grabowski, 2003]. In most cases its orthodontic treatment in deciduous dentition is not indicated, contrary to what is recommended for the transverse and sagittal discrepancies [Tschill et al., 1997].

Oral habits as risk factors for anterior open bite in the deciduous and mixed dentition crosssectional study

ABSTRACT

Aim Anterior open bite (AOB) is an occlusal anomaly commonly associated with oral habits (OH). The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of OH as a risk factor for the AOB. Material and methods A group of children aged between 3 and 12 years were observed. The statistical methodology included independent chi-square test, Fishers exact test and binary logistic regression. Results The frequency of oral habits was of 43.5% in the deciduous dentition and 54.2% in the mixed dentition. There was a statistically signicant association of pacier sucking: 61.7 and 16.1 odd ratios (OR), and tongue thrust: 3.9 and 9.2 OR with AOB in both groups, respectively. Thumb sucking occurred only in the deciduous dentition with 5.6 OR. Conclusions OH and AOB have a high frequency in children. They hinder the normal development of dental and skeletal structures. As OH are risk factors for AOB, the damaging habits most frequently associated are: pacier sucking, thumb sucking, and tongue thrust. Due to the correlation between the prevalence of AOB and OH, prevention strategies incorporating psychological data related to children should be integrated into a national public health programme. Keywords Anterior open bite; Deciduous dentition; Dysfunctional habits; Epidemiology; Malocclusion; Mixed dentition; Oral habit; Public health.

Material and methods

Data from children from all social classes at nine schools in the parish of Paranhos, Porto, were collected and the Ethical Council of the Faculty of Dentistry, Porto University, approved the study. After applying the following exclusion

EUROPeAN JOURNAL OF PAeDIATRIC DeNTISTRY VOL. 14/4-2013

299

URZAL V., BRAGA A.C. AND FERREIRA A.P.

criteria: children under 3 and over 12 years old and children using orthodontic appliances, the sample was reduced to 568 children. This nal sample was subdivided into groups A and B, according to the chronological age. Group A consisted of children aged 6 or under, i.e. with deciduous dentition (average 5.39 years old, standard deviation 0.94 years), and group B, children between 7 and 12 years old, with mixed dentition (average 8.23 years old, standard deviation 0.99 years). The group of children with primary dentition consisted of 88 girls (46.6%) and 101 boys (53.4%). The mixed dentition grouped 195 girls (51.5%) and 184 boys (48.5%). The study followed the recommendations of the World Health Organization. The informed consent and all measurements were taken at the clinic of the Faculty of Dentistry. All children lled a questionnaire and underwent a clinical examination (on a dental chair, directly with a buccal mirror No. 5, a periodontal probe with depth marks, forceps, a disposable spatula, retractors and a millimetre ruler of the lips and cheeks). The evaluation included the following items: existence of abnormal pressure habits such as sucking (pacier, lip, lingual, thumb or other), lip-biting, nail-biting, tongue thrust, cheek-sucking and biting. The statistical analysis was performed by the program IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 for Windows and in R version 2.13.0 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL). The decision-making rule consists of detecting statistical signicance for a level of 0.05.

Results

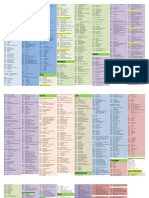

The prevalence of OH for the deciduous dentition was of 43.5% with 95% CI [36.4%, 51.0%] and of 54.2% with 95% CI [48.9%; 59.3%] for the mixed dentition. To evaluate the distribution of the habits in each group, we used exploratory examination by means of the relative frequencies of each group. According to the

AOB

results listed in Table I, nail biting showed prominence in group A, followed by tongue thrust, pacier, thumb sucking and lip-biting, lip-sucking, other sucking, lingual sucking, cheek-sucking and cheekbiting, and other habits. As for group B, the habit of nail biting showed the highest frequency, followed by lip-biting, tongue thrust, thumb-sucking, and lip-sucking, lingual sucking, pacier, or sucking, cheek-sucking and -biting, and or habits (however children could have one or more OH). In individuals with AOB (with the prevalence of 16.9% in deciduous dentition and 11.4% in mixed dentition) [Urzal et al., 2012] the prevalence of OH in the deciduous dentition was of 73.3% with 95% CI [53.8%, 87.0%] and in the mixed dentition was of 76.2% with 95% CI [60.2%, 87.4%]. In individuals with OH the prevalence of AOB in the deciduous dentition was of 29.7% with 95% CI [19.9%, 41.6%] and in the mixed dentition was of 16.3% with 95% CI [11.6%, 22.4%]. In children with AOB and deciduous dentition, the OH are different compared with the children in the total sample being the prevalence higher in all OH except for the lip-sucking and other habits, and in mixed dentition the exception is lip-biting and other habits. In order to evaluate the possible association of different OH with AOB, an analysis on 2x2 tables of the coefcient of association odds ratio (OR) was performed. Considering AOB as the dependant variable, we evaluated the effects of different factors (habits) in groups A and B according to age. In general, it is considered that the odds ratio (OR) of the dependent variable Y=1 (presence of AOB) versus the response variable with the value Y=0 (no AOB) for values of the independent variable (factor); x=a versus x=b. The results are listed in Table 2. Thereby, in the deciduous dentition there is a statistically signicant association between pacier, thumb-sucking and tongue thrust with the existence of AOB, 61.7, 5.6 and 3.9 respectively. In the mixed dentition the risk factors for AOB are paciers

Global

GROUP A

n

Pacier-sucking Lip-sucking Lingual sucking Thumb-sucking Other sucking Lip-biting Nail biting Tongue thrust Cheek-sucking and -biting Other habits 9 1 2 5 0 2 6 5 1 0

GROUP B

%

30.0% 3.3% 6.7% 16.7% 0.0% 6.7% 20,0% 16.7% 3.3% 0.0%

GROUP A

%

4.8% 9.5% 2.4% 7.1% 0.0% 9.5% 45.2% 19.0% 2.4% 0.0%

GROUP B

%

5.7% 4.0% 2.9% 5.7% 3.4% 5.8% 18.4% 6.9% 1.1% 0.6%

n

2 4 1 3 0 4 19 8 1 0

n

10 7 5 10 6 10 32 12 2 1

n

3 16 4 16 3 37 147 16 3 2

%

0.8% 4.4% 1.1% 4.4% 0.8% 10.2% 40.6% 4.4% 0.8% 0.6%

TABLE 1 Prevalence of OH in children with AOB and overall for the two types of dentition.

300

EUROPeAN JOURNAL OF PAeDIATRIC DeNTISTRY VOL. 14/4-2013

ORAL HABITS AS RISK FACToRS FoR ANTERIoR oPEN BITE

GROUP A

OR 95% OR C.I.OR

Lower Pacier-sucking Lip-sucking Lingual sucking Thumb-sucking Other sucking Lip-biting Nail biting Tongue thrust Cheek-sucking or biting Other habits 61.7* 7.4 0.8 3.4 5.6* 1.1 1.1 3.9* 5.0 0.1 0.5 1.5 0.2 0.4 1.2 0.3 Upper 512.2 6.8 21.2 20.8 5.2 2.9 13.4 81.7 16.1* 2.7 2.6 1.8 0.9 1.3 9.2* 2.6 -

GROUP B

OR 95% OR C.I.OR

Lower Upper 1.4 0.8 0.3 0.5 0.3 0.7 3.3 0.3 181.0 8.9 25.5 6.7 2.7 2.4 26.2 25.5 -

TABle 2 Estimated values for OR and respective CI.95%. (OR=16.1) and tongue thrust (OR=9.2).

Discussion

The AOB frequency decreases from deciduous to mixed dentition, from 16.9% to 11.4% [Urzal V et al., 2012], which is in agreement with published data where the rate varies from 3-41% in deciduous dentition and 1-15% in mixed dentition [Stahl and Grabowski, 2003]. In our study the OH increased from 43.5% to 54.2%, as already observed in the study of Stahl et al. [2007] conducted in Germany (28.6% to 46.6%), but with a lower frequency. The percentage of OH in Portuguese kids was similar to Valencian (53%, 4-11 years), less than Catalan (84%, 3-7 years) [Cahuana et al., 1998], higher than Croatian (33.37%, 6-11 years) [Bosnjak et al., 2002] and Indian subjects (29.7 %, 3-16 years) [Shetty and Munshi, 1998; Gallardo and Cencillo, 2005]. For Bowden [1966], approximately one third of mixed dentition children with prolonged sucking habits have AOB. While for Baccetti et al. [1997], one in four children with hyperdivergent facial pattern (FMA>25, S-Go/N-Me<0.62, ANS-Me/N-Me>0.55) develops this malocclusion [Cozza P et al., 2005]. In the study of Cozza et al. [2005] in patients with AOB, the prevalence of sucking habits and facial hyperdivergency was of 36.3% representing four times the prevalence of these two factors in subjects without AOB (9.1%). OH increase from the deciduous to the mixed dentition in Portuguese children, but the proportions change with a greater increase of the nail biting and the lip-biting. The fact that nail biting has the higher prevalence in both groups may be related to the approach of the average age between the two groups (5.39 and 8.23 years). In the group with OH there is also an increased prevalence of AOB from A to B, whose prevalence was

73.3% in deciduous dentition and 76.2% in mixed dentition, as demonstrated by other studies [Stahl et al., 2007], namely Fukuta et al. [1996] and Farsi et Salama [1997] in deciduous dentition (higher prevalence of AOB and sucking habits) [Cozza et al., 2005]. In the study of Cozza et al., the prevalence of OH in mixed dentition with AOB is 63,4% and 28% without AOB. They concluded that OH are risk factors for developing AOB in mixed dentition, however consider that the studies are contradictory when evaluating the habits that inuence occlusion and cause this malocclusion [Cozza et al., 2005]. The AOB is early observable in children with pacier sucking when compared with the thumb sucking [Larsson, 1994], with 61.7 and 5.6 times more risk to develop this occlusal anomaly, respectively. However, in the deciduous dentition, a crossbite is more related to the pacier than to thumb sucking [Larsson E, 1994]. This should be corrected before ossication of the midpalatal suture [Enlow, 1966] as early as possible, therefore reducing or preventing the asymmetric growth of the jaws [Thilander et al., 2001] and asymmetric bite forces [Sonnesen et al., 2002; Tausche et al., 2004]. Thumb sucking can lead to AOB due to decreased vertical growth of the alveolar process, pro-inclination of maxillary incisors, anterior displacement and rotation of the maxilla and subsequent posterior crossbite, and pro- or retroinclination of the lower incisors, depending on the clamping force between the lower lip and tongue activity during suction [Larsson, 1994]. In this study it was found a statistically signicant association between AOB and thumb sucking only in the deciduous dentition. The size, posture, tongue muscle tone and function are supposed to be responsible for contributing to malocclusion because the change in soft tissue pressure in the rest position is the most important factor due to its continuous effect [Stahl et al., 2007]. That is, the changes in one region coincide with neuromuscular adjustments in the coordination of the entire system, inducing multifunctional disorders [Stahl F et al., 2007]. The rest position of the tongue is in contact with the palate extending to the palatal part of the alveolar process [Kittel,1998], stimulating their growth [Stahl et al., 2007]. In pathological states, it can be positioned between the anterior and/or the posterior teeth or towards the antero-inferior [Stahl et al., 2007], thereby, and together with the lips, playing an important role in the dentition [Proft, 1975; Brandt, 1977]. In 1984, tongue thrust had been already associated with excessive anterior vertical dimension by Langlade. He knew that the major problem was to determine and eliminate its functional imbalance [Langlade, 1984]. Gile [1972] also veried in his study that the presence of a tongue habit is related to AOB [Smithpeter and Covell, 2010]. There is a statistically signicant association between the AOB and the habit of pacier sucking and tongue thrust in deciduous and mixed dentition. The risk for

EUROPeAN JOURNAL OF PAeDIATRIC DeNTISTRY VOL. 14/4-2013

301

URZAL V., BRAGA A.C. AND FERREIRA A.P.

developing AOB, when compared with children who do not have these habits, is 61.7 and 16.1 times higher in both dentitions for the habit of pacier, and 3.9 and 9.2 times higher for the habit of tongue thrust. The absence of paciers before the age of 6 induces the spontaneous correction of AOB in up to 70.1% of the cases according to Gis et al. [2011]. After two, three or four years of age, depending on the investigators, the adverse effects of sucking habits can manifest themselves; therefore, the transversal, the vertical and the sagittal occlusal relations should be evaluated at these ages and proper treatment must begin at this stage [Gis et al., 2011]. However, Klocke et al. [2002] found that spontaneous closure of AOB generally occurs before the age of 12. Once the habit is eliminated and being the child in growth phase, a self-correction of the AOB occurs [Gis et al., 2011; Larsson, 1994; Tausche et al., 2004] due to the cellular growth process, maintaining, however, the basal skeletal effect [Larsson, 1994]. This occurrence will depend on the duration and intensity of the habit [Brandt, 1977; Langlade, 1984]. It is necessary to recognise and eliminate functional stress factors in order to prevent them [Stahl and Grabowski, 2003]. Early treatment should take into consideration the severity of the malocclusion and its impact on the neuromuscular system, preventing asymmetric alveolar bone development and disturbances in the permanent dentition [Kluemperer et al., 2000; Tausche et al., 2004]. It also inhibits or, at least, reduces the severity and the progression of the malocclusion [Bishara et al., 1998; Tausche et al., 2004]. Due to the inuence of OH in growing patients, some therapeutic protocols with xed or removable appliances should be followed in order to eliminate, improve or at least control the increased vertical dimension [Cozza et al., 2005].

References

Baccetti T, Manetti I, Tollaro I. Correlazioni tra le caratteristiche del combaciamento interincisivo e lequilibrio scheletrico cranio-facciale. Nota I. Overbite e parametri scheletrici verticali. Ortognat It 1997;6:641-8. Bishara SE, Justus R, Graber TM. Proceedings of the workshop discussions on early treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;113:5-6. Bosnjak A, Vucicevic-Boras V, Miletic I, Bozic D, Vukelja M. Incidence of oral habits in children with mixed dentition. J Oral Rehabil 2002;29:902-5. Bowden BD. A longitudinal study of the effects of digit- and dummy-sucking. Am J Orthod 1966;52:887-901. Brandt S. JCO interviews Dr.William R. Prott on the proper role of myofunctional therapy. J Clin Orthod 1977;11:101-15. Cahuana A, Moncunill J, Roca J, Valero C. Hbits de succi no nutritiva en edat preescolar i la seva relaci amb les maloclusions. Estudi prospectiu de 200 nens. Pediatr Catalana 1998;58:332-7. Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, Mucedero M, Polimenie A. Sucking habits and facial hyperdivergency as risk factors for anterior open bite in the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005;128:517-9. Doshi UH, Bhad WA. Spring-loaded bite-blocks for early correction of skeletal open bite associated with thumb sucking. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011;140:11520. Enlow DH. A morphogenetic analysis of facial growth. Am J Orthod 1966;52:283-99. Farsi NM, Salama FS. Sucking habits in Saudi children: prevalence, contributing factors and effects on the primary dentition. Pediatr Dent 1997;19:28-33. Fukuta O, Braham RL, Yokoi K, Kurosu K. Damage to the primary dentition resulting from thumb and nger (digit) sucking. J Dent Child 1996;63:403-7. Gallardo VP, Cencillo CP. Prevalencia de los hbitos bucales y alteraciones dentarias en escolares valencianos. An Pediatr (Barc) 2005;62:261-5. Gile RA. A longitudinal cephalometric evaluation of orthodontically treated anterior openbites [thesis]. Seattle: University of Washington; 1972. Giuntini V, Franchi L, Baccetti T, Mucedero M, Cozza P. Dentoskeletal changes associated with xed and removable appliances with a crib in open-bite patients in the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008 Jan;133:77-80. Gis EG, Vale MP, Paiva SM, Abreu MH, Serra-Negra JM, Pordeus IA. Incidence of malocclusion between primary and mixed dentitions among Brazilian children A 5-year longitudinal study. Angle Orthod 2012;82:495-500. Ingervall B, Thilander B. Relationship between facial morphology and activity of the masticatory muscles. J Oral Rehab 1974;1:131-47. Kittel A. Myofunktionelle Therapie. Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner Verlag 1998. Klocke A, Nanda RS, Kahl-Nieke B. Anterior open bite in the deciduous dentition: longitudinal follow-up and craniofacial growth considerations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2002;122:353-8. Kluemperer GT, Beeman CS, Hicks EP. Early orthodontic treatment: what are the imperatives? J Am Dent Assoc 2000,131:613-20. Landouzy et al.. The tongue: deglutition, orofacial functions and craniofacial growth. Inter Orthod 2009;7:227-256. Langlade M. The problem of large anterior vertical excess. Rev Orthop Dento Faciale 1984;18:145-205. Larsson E. Articial sucking habits: etiology, prevalence and effect on occlusion. Int J Orofacial Myology 1994;20:10-21. Linder-Aronson S. Adenoids: their effect on mode of breathing and nasal airow and their relationship to characteristics of the facial skeleton and dentition. Acta Otolaryngol Scand (suppl.), 1970. Linder-Aronson S. Effects of adenoidectomy on the dentition and facial skeleton over a period of ve years. In: Cook JT, ed. Transactions of the Third International Orthodontic Congress. The C.V. Mosby Co. St. Louis, 1975. Mller E. The chewing apparatus. Acta Physiol 1966;69:571-74. Nielsen IL. Vertical malocclusions: etiology, development, diagnosis and some aspects of treatment. Angle Orthod 1991;61:247-60. Proft WR, Mason RM. Myofunctional therapy for tongue-thrusting: background and recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc 1975;90:403-11. Shetty SR, Munshi AK. Oral Habits in children: A prevalence study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 1998;16:61-6. Smithpeter J, Covell D. Relapse of anterior open bites treated with orthodontic appliances with and without orofacial myofunctional therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010;137:605-14. Sonnesen L, Bakke M, Solow B. Bite force in pre-orthodontic children with unilateral crossbite. Eur J Orthod 2001;23:741-9. Stahl F, Grabowski R. Orthodontic ndings in the deciduous and early mixed dentition-inferences for a preventive strategy. J Orofac Orthop 2003;64:401-16. Stahl F, Grabowski R, Gaebel M, Kundt G. Relationship between Occlusal Findings and Orofacial Myofunctional Status in Primary and Mixed Dentition Part II: Prevalence of Orofacial Dysfunctions. J Orofac Orthop 2007;68:7490. Tausche E, Luck O, Harzer W. Prevalence of malocclusions in the early mixed dentition and orthodontic treatment need. Eur J Orthod 2004; 237-244. Thilander B, Pena L, Infante C, Parada SS, de Mayorga C. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in children and adolescents in Bogota, Colombia. An epidemiological study related to different stages of dental development. Eur J Orthod 2001;23:153-67. Tschill P, Bacon W, Sonko A. Malocclusion in the deciduous dentition of Caucasian Children. Eur J Orthod 1997;361-367. Urzal V, Braga AC,Pinho AF. The prevalence of anterior open bite in Portuguese children during deciduous and mixed dentition correlations for a preventive strategy. Inter Orthod Epub 2012 Dez.

Conclusion

Since OH are implicit in the development of dentition, early treatment measures such as orthodontic preventive treatment and children psychological information are important to reduce AOB, which is one of the most relevant problems in public health. A screening of children in primary and early mixed dentition should be done for malocclusions and orofacial dysfunctions, as soon as possible. Preventive strategies may include a national public health programme to reduce the risk factors of AOB and, consequently, to reduce the incidence of this anomaly.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conicts of interest concerning this article.

302

EUROPeAN JOURNAL OF PAeDIATRIC DeNTISTRY VOL. 14/4-2013

You might also like

- An Esthetic Removable Inclined Plane - Jco - Pearls - Volume IV Number 5 May 2020 Page 275Document2 pagesAn Esthetic Removable Inclined Plane - Jco - Pearls - Volume IV Number 5 May 2020 Page 275APinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Management of A Severely Compromised Periodontal Patient - Case ReportDocument10 pagesInterdisciplinary Management of A Severely Compromised Periodontal Patient - Case ReportAPinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Clemente MP Mendes J Vardasca R Moreira A Branco CA Ferreira AP Amarante JMDocument6 pagesClemente MP Mendes J Vardasca R Moreira A Branco CA Ferreira AP Amarante JMAPinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Condylar Displacement Between Three Biotypological Facial Groups by Using Mounted Models and A Mandibular Position Indicator - 2014Document8 pagesComparison of Condylar Displacement Between Three Biotypological Facial Groups by Using Mounted Models and A Mandibular Position Indicator - 2014APinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Validity of 2D Lateral Cephalometry in Orthodontics - A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesValidity of 2D Lateral Cephalometry in Orthodontics - A Systematic ReviewAPinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Craniofacial Morphology of Wind and String Instrument Players: A Cephalometric Study.Document9 pagesCraniofacial Morphology of Wind and String Instrument Players: A Cephalometric Study.APinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Artigo Do Jornal "As Artes Entre As Letras"Document1 pageArtigo Do Jornal "As Artes Entre As Letras"APinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Different Manifestations of Class II Division 2 Incisor Retroclination and Their Association With Dental AnomaliesDocument8 pagesDifferent Manifestations of Class II Division 2 Incisor Retroclination and Their Association With Dental AnomaliesAPinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- KJO14-004 - Comparison of Condylar Displacement Between Three Biotypological Facial Groups by Using Mounted Models and A Mandibular Position IndicatorDocument8 pagesKJO14-004 - Comparison of Condylar Displacement Between Three Biotypological Facial Groups by Using Mounted Models and A Mandibular Position IndicatorAPinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Artigo Different Manifestations of Class II Division 2 Incisor Retroinclination. A Morphologic StudyDocument7 pagesArtigo Different Manifestations of Class II Division 2 Incisor Retroinclination. A Morphologic StudyAPinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- ICD - ProgrammeDocument7 pagesICD - ProgrammeAPinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- Poster Semana Das Artes FMDUP - 2010Document1 pagePoster Semana Das Artes FMDUP - 2010APinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- 1-MITOS® - Simplified Multisystem Individualized Orthodontic TreatmentDocument4 pages1-MITOS® - Simplified Multisystem Individualized Orthodontic TreatmentAPinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- The Orthodontic Sports Protection Appliance (JCO, Vol. XLIV, Number 1, 2010)Document4 pagesThe Orthodontic Sports Protection Appliance (JCO, Vol. XLIV, Number 1, 2010)APinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- MITOS PostulatesDocument5 pagesMITOS PostulatesAPinhaoFerreiraNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 2 Months To LiveDocument26 pages2 Months To LivedtsimonaNo ratings yet

- Empowerment Through Nature's Wishing Tree (The Banyan TreeDocument9 pagesEmpowerment Through Nature's Wishing Tree (The Banyan TreeAndrea KoumarianNo ratings yet

- 2021-2022 Sem 2 Lecture 2 Basic Tests in Vision Screenings - Student VersionDocument123 pages2021-2022 Sem 2 Lecture 2 Basic Tests in Vision Screenings - Student Versionpi55aNo ratings yet

- The SCARE Statement Consensus-Based Surgical Case ReportDocument7 pagesThe SCARE Statement Consensus-Based Surgical Case ReportIhsan KNo ratings yet

- Understanding Mental Illness Across CulturesDocument6 pagesUnderstanding Mental Illness Across Culturesjessaminequeency4128No ratings yet

- Malaysia's Healthcare Industry Faces Economic ChallengesDocument10 pagesMalaysia's Healthcare Industry Faces Economic ChallengesAhmad SidqiNo ratings yet

- Cold TherapyDocument27 pagesCold Therapybpt2100% (1)

- Panduan Kode ICDDocument3 pagesPanduan Kode ICDDadang MardiawanNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Scabies and Crusted VariantsDocument4 pagesTreatment of Scabies and Crusted Variantsduch2020No ratings yet

- Observational Tools For Measuring Parent-Infant InteractionDocument34 pagesObservational Tools For Measuring Parent-Infant Interactionqs-30No ratings yet

- Tfios Mediastudyguide v4Document7 pagesTfios Mediastudyguide v4api-308995770No ratings yet

- Colon Neuroendocrine Tumour Synoptic CAPDocument9 pagesColon Neuroendocrine Tumour Synoptic CAPMichael Herman ChuiNo ratings yet

- Dental CementsDocument208 pagesDental CementsAkriti Goel33% (3)

- CPG 2013 - Prevention and Treatment of Venous ThromboembolismDocument170 pagesCPG 2013 - Prevention and Treatment of Venous ThromboembolismMia Mus100% (1)

- Refacere Dinti Frontali Cu Cape de CeluloidDocument5 pagesRefacere Dinti Frontali Cu Cape de CeluloidSorina NeamțuNo ratings yet

- Current Management of Amaurosis Fugax: Progress ReviewsDocument8 pagesCurrent Management of Amaurosis Fugax: Progress ReviewsAnuj KodnaniNo ratings yet

- Daily sales and expense recordsDocument29 pagesDaily sales and expense recordselsa fanny vasquez cepedaNo ratings yet

- Wound Management ProcedureDocument51 pagesWound Management ProcedureSisca Dwi AgustinaNo ratings yet

- 133-Article Text-648-3-10-20190525 PDFDocument6 pages133-Article Text-648-3-10-20190525 PDFyantiNo ratings yet

- Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm (ROCA) Using Serial CA 125Document9 pagesRisk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm (ROCA) Using Serial CA 125primadian atnaryanNo ratings yet

- Dr. Jinitha K.S. - Assorted Essays On Classical and Technical LiteratureDocument137 pagesDr. Jinitha K.S. - Assorted Essays On Classical and Technical LiteratureSasi KadukkappillyNo ratings yet

- 30th Report Bogus Unregistered Deregistered HealthPract-1Document106 pages30th Report Bogus Unregistered Deregistered HealthPract-1Paul GallagherNo ratings yet

- Ewert WCNDT Standards 2012 04 PDFDocument38 pagesEwert WCNDT Standards 2012 04 PDFJorge Manuel GuillermoNo ratings yet

- Klinefelter SyndromeDocument6 pagesKlinefelter Syndromemeeeenon100% (1)

- TESCTflyer 2012Document11 pagesTESCTflyer 2012Marco TraubNo ratings yet

- The Endocrine Pancreas: Regulation of Carbohydrate MetabolismDocument61 pagesThe Endocrine Pancreas: Regulation of Carbohydrate MetabolismFatima OngNo ratings yet

- What Is Stress PDFDocument4 pagesWhat Is Stress PDFmps itNo ratings yet

- Rekapitulasi Laporan Psikotropika Bandung BaratDocument8 pagesRekapitulasi Laporan Psikotropika Bandung BaratFajarRachmadiNo ratings yet

- Reproductive Health BillDocument22 pagesReproductive Health BillPhoebe CasipitNo ratings yet

- Ucmc DepartmentsDocument39 pagesUcmc DepartmentsAllen ZhuNo ratings yet