Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Strategy and The Internet

Uploaded by

arturoglezmal2Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Strategy and The Internet

Uploaded by

arturoglezmal2Copyright:

Available Formats

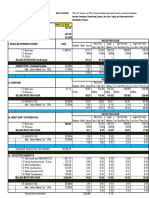

EXECUTIVE SUMMAR8ES > March 2001

Page 62

Page 80

Page 92

Strategy and the Internet

Michael E. Porter Reprint R0103D

Building the Emotional Intelligence of Groups

Vanessa Urch Druskat and Steven B. Wolff Reprint R0103E

Not All M&As Are Alikeand That Matters

Joseph L Bower Reprint R0103F

Many of the pioneers of Intemet business, both dot-coms and established companies, have competed in ways that violate nearly every precept of good strategy. Rather than focus on profits, they have chased customers indiscriminately through discounting, channel incentives, and advertising. Rather than concentrate on delivering value that earns an attractive price from customers, they have pursued indirect revenues such as advertising and click-through fees. Rather than make trade-offs, they have rushed to offer every conceivable product or service. It did not have to be this way-and it does not have to be in the future. When it comes to reinforcing a distinctive strategy, Michael Porter argues, the Intemet provides a better technological platform than previous generations of IT. Gaining competitive advantage does not require a radically new approach to business; it requires building on the proven principles of effective strategy. Porter argues that, contrary to recent thought, the Internet is not disruptive to most existing industries and established companies. It rarely nullifies important sources of competitive advantage in an industry; it often makes them even more valuable. And as aU companies embrace Intemet technology, the Intemet itself will be neutralized as a source of advantage. Robust competitive advantages will arise instead from traditional strengths such as unique products, proprietary content, and distinctive physical activities. Intemet technology may be able to fortify those advantages, but it is unlikely to supplant them. Porter debunks such Intemet myths as first-mover advantage, the power of virtual companies, and the multiplying rewards of network effects. He disentangles the distorted signals from the marketplace, explains why the Intemet complements rather than cannibalizes existing ways of doing business, and outlines strategic imperatives for dot-coms and traditional companies.

The management world knows by now that to be effective in the workplace, an individual needs high emotional intelligence. What isn't so well understood is that teams need it, too. Citing such companies as IDEO, HewlettPackard, and the Hay Group, the authors show that high emotional intelligence is at the heart of effective teams. These teams behave in ways that build relationships both inside and outside the team and that strengthen their ability to face challenges. High group emotional intelligence may seem like a simple matter of putting a group of emotionally intelligent individuals together. It's not. For a team to have high EI, it needs to create norms that establish mutual trust among members, a sense of group identity, and a sense of group efficacy. These three conditions are essential to a team's effectiveness because they are the foundation of true cooperation and collaboration. Group EI isn't a question of dealing with a necessary evil-catching emotions as they bubble up and promptly suppressing them. It's about bringing emotions deliberately to the surface and understanding how they affect the team's work. Group emotional intelligence is about exploring, embracing, and ultimately relying on the emotions that are at the core of teams.

Despite all that's been written about mergers and acquisitions, even the experts know surprisingly little about them. The author recently headed up a year-long study sponsored by Harvard Business School on the subject of M&A activity. In-depth findings will emerge over the next few years, but the research has already revealed some interesting results. Most intriguing is the notion that, although academics, consultants, and businesspeople lump M&As together, they represent very different strategic activities. Acquisitions occur for the following reasons: to deal with overcapacity through consolidation in mature industries; to roll up competitors in geographically fragmented industries; to extend into new products and markets; as a substitute for R&D; and to exploit eroding industry boundaries by inventing an industry. The different strategic intents present distinct integration challenges. For instance, if you acquire a company because your industry has excess capacity, you have to determine which plants to shut down and which people to let go. If, on the other hand, you buy a company because it has developed an important technology, your challenge is to keep the acquisition's best engineers from jumping ship. These scenarios require the acquiring company to engage in nearly of)posite managerial behaviors. The author explores each type of M&Aits strategic intent and the integration challenges created by that intent. He underscores the importance ofthe acquiring company's assessment of the acquired group's culture. Depending on the type of M&A, approaches to the culture in place must vary, as will the level to which culture interferes with integration. He draws from the experiences of such companies as Cisco, Viacom, and BancOne to exemplify the different kinds of M&As.

164

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Citadel Letter Dec 22Document3 pagesCitadel Letter Dec 22ZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Basics of Accounting eBookDocument1,190 pagesBasics of Accounting eBookArun Balaji82% (11)

- Branding For Impact by Leke Alder PDFDocument22 pagesBranding For Impact by Leke Alder PDFNeroNo ratings yet

- Project On SpicesDocument96 pagesProject On Spicesamitmanisha50% (6)

- The Dynamics of Product Innovation and Firm CompetencesDocument27 pagesThe Dynamics of Product Innovation and Firm Competencesarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- MDRT 2010 Proceedings Table of ContentsDocument3 pagesMDRT 2010 Proceedings Table of ContentsErwin Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- A NATIONAL STUDY of Human Resource Practices, Turnover, and Customer Service in The Restaurant Industry.Document32 pagesA NATIONAL STUDY of Human Resource Practices, Turnover, and Customer Service in The Restaurant Industry.ROCUnitedNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology in ManagementDocument18 pagesResearch Methodology in Managementarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- Rationality Foolishness and Adaptive IntelligenceDocument14 pagesRationality Foolishness and Adaptive Intelligencearturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- The Choice Among Acquisitions Alliances and Divestiture SDocument26 pagesThe Choice Among Acquisitions Alliances and Divestiture Sarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- International Management TypologyDocument29 pagesInternational Management TypologykalexyzNo ratings yet

- The Destructive Pursuit of Idealized GoalsDocument11 pagesThe Destructive Pursuit of Idealized GoalsArturo GonzalezNo ratings yet

- The Lack of Consensus About Strategic ConsensusDocument19 pagesThe Lack of Consensus About Strategic Consensusarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- The Economic Geography of The Internet AgeDocument26 pagesThe Economic Geography of The Internet Agearturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- The Lack of Consensus About Strategic ConsensusDocument19 pagesThe Lack of Consensus About Strategic Consensusarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- The Choice Among Acquisitions Alliances and Divestiture SDocument26 pagesThe Choice Among Acquisitions Alliances and Divestiture Sarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- Theory and Research in Strategic ManagementDocument40 pagesTheory and Research in Strategic Managementarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- The Economic Geography of The Internet AgeDocument26 pagesThe Economic Geography of The Internet Agearturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- The Relational ViewDocument20 pagesThe Relational Viewarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- What Have We Learned From Generic Competitive StrategyDocument28 pagesWhat Have We Learned From Generic Competitive Strategyarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- Theresource Basedviewofthefirm1Document17 pagesTheresource Basedviewofthefirm1arturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- Theresource Basedtheory DisseminationandmaintrendsDocument16 pagesTheresource Basedtheory Disseminationandmaintrendsarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- Strategic Aligment ITDocument10 pagesStrategic Aligment ITArturo González MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- What Have We Learned From Generic Competitive StrategyDocument28 pagesWhat Have We Learned From Generic Competitive Strategyarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- Working Abroad Working With OthersDocument17 pagesWorking Abroad Working With Othersarturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- Who Directs Strategic ChangeDocument25 pagesWho Directs Strategic Changearturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- Wiltbank Et Al What Do The Next (ENCONTRO 7)Document18 pagesWiltbank Et Al What Do The Next (ENCONTRO 7)hym82No ratings yet

- Report Align ConceptsDocument4 pagesReport Align ConceptsArturo González MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- DictatorshipDocument3 pagesDictatorshiparturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- DictatorshipDocument3 pagesDictatorshiparturoglezmal2No ratings yet

- Gibbons IntroduccionDocument13 pagesGibbons IntroduccionArturo González MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Managing With Agile - Peer-Review Rubric (Coursera)Document8 pagesManaging With Agile - Peer-Review Rubric (Coursera)awasNo ratings yet

- Str. Poieni Nr. 1 Wernersholmvegen 5 5232 Paradis NORWAY: Seatrans Crewing A/S Constanta Filip, Dumitru IulianDocument1 pageStr. Poieni Nr. 1 Wernersholmvegen 5 5232 Paradis NORWAY: Seatrans Crewing A/S Constanta Filip, Dumitru Iuliandumitru68No ratings yet

- Guru Kirpa ArtsDocument8 pagesGuru Kirpa ArtsMeenu MittalNo ratings yet

- Oxford Said MBA Brochure 2017 18 PDFDocument13 pagesOxford Said MBA Brochure 2017 18 PDFEducación ContinuaNo ratings yet

- Top US Companies by RegionDocument88 pagesTop US Companies by RegionLalith NeeleeNo ratings yet

- ENSP - Tender No.0056 - ENSP - DPE - AE - INV - 19 - Supply of A Truck Mounted Bundle ExtractorDocument2 pagesENSP - Tender No.0056 - ENSP - DPE - AE - INV - 19 - Supply of A Truck Mounted Bundle ExtractorOussama AmaraNo ratings yet

- Copier CoDocument9 pagesCopier CoHun Yao ChongNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument10 pagesResearchElijah ColicoNo ratings yet

- Adjustment of Contract Prices: Using Cida Formula MethodDocument10 pagesAdjustment of Contract Prices: Using Cida Formula MethodHarshika Prasanganie AbeydeeraNo ratings yet

- Netflix Survey ReportDocument7 pagesNetflix Survey ReportShantanu Singh TomarNo ratings yet

- PSP Study Guide 224 Q & A Revision Answers OlnyDocument214 pagesPSP Study Guide 224 Q & A Revision Answers OlnyMohyuddin A Maroof100% (1)

- Powerpoint Presentation To Accompany Heizer and Render Operations Management, 10E Principles of Operations Management, 8EDocument45 pagesPowerpoint Presentation To Accompany Heizer and Render Operations Management, 10E Principles of Operations Management, 8EAnum SaleemNo ratings yet

- Arizona Exemptions 7-20-11Document1 pageArizona Exemptions 7-20-11DDrain5376No ratings yet

- PhonePe Statement Mar2023 Mar2024Document59 pagesPhonePe Statement Mar2023 Mar2024Navneet ChettiNo ratings yet

- City Gas Distribution Projects: 8 Petro IndiaDocument22 pagesCity Gas Distribution Projects: 8 Petro Indiavijay240483No ratings yet

- Muthoot FinanceDocument58 pagesMuthoot FinanceNeha100% (2)

- Dwnload Full Retailing 8th Edition Dunne Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Retailing 8th Edition Dunne Test Bank PDFjayden4r4xarnold100% (14)

- Dominos PizzaDocument14 pagesDominos PizzahemantNo ratings yet

- Full PFSDocument61 pagesFull PFSrowel manogNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking: by Cheryl Marlitta Stefia. S.T., M.B.A., QrmaDocument18 pagesDesign Thinking: by Cheryl Marlitta Stefia. S.T., M.B.A., QrmaRenaldiNo ratings yet

- Centum Rakon India CSR Report FY 2020-21Document14 pagesCentum Rakon India CSR Report FY 2020-21Prashant YadavNo ratings yet

- Ihrm GPDocument24 pagesIhrm GPMusa AmanNo ratings yet

- Fresher Finance Resume Format - 4Document2 pagesFresher Finance Resume Format - 4Dhananjay KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Security agency cost report for NCRDocument25 pagesSecurity agency cost report for NCRRicardo DelacruzNo ratings yet