Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CH 13

Uploaded by

Adi SoodOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CH 13

Uploaded by

Adi SoodCopyright:

Available Formats

CH 13: The Weighted-Average

Cost of Capital

1 06/04/2014

CeoLhermals Cost of Capital

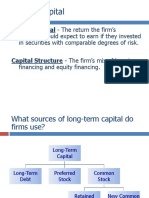

Capital Structure - 1he flrms mlx of long-term

financing [debt and equity].

Cost of Capital - 1he reLurn Lhe flrms lnvesLors

could expect to earn if they invested in securities

with comparable risk.

The WACC represents a standard discount rate for

average risk projects.

For higher-than-average risk projects, the WACC can

be adjusted up; and for lower-than-average risk

projects it can be adjusted down.

06/04/2014 2

CeoLhermals CosL of CaplLal

Calculate the company cost of capital for Geothermal

given the following capital structure, and assuming it

pays 8% for debt and 14% for equity.

Portfolio return = 0.3 8% + 0.7 14% = 12.2%

100% $647 Assets Value Market

70% $453 Equity Value Market

30% $194 Debt Value Market

06/04/2014 3

Weighted average cost of capital (WACC)

The cost of capital with debt (no taxes)

Suppose a firm is financed by both debt and

equity. We denote the values of the outstanding

debt and the equity as D and E, respectively. So

the total market value of the firm, V = D+E.

The cost of capital must be based on the

securlLles markeL values noL book values.

E D

E D

asset

r

V

E

r

V

D

V

E r D r

r + =

+

= = =

investment of value

income total

WACC

4 06/04/2014

WACC: an example

Consider a firm whose debt has a market value of $40

million and whose stock has a market value of $60

million (3 million outstanding shares of stock, each

selling for $20 per share). The firm pays 15% rate of

interest on its new debt and equity investors want

25%, what is the firms WACC?

% 21 % 25

60 40

60

% 15

60 40

40

equity in proportion debt in proportion WACC

=

+

+

+

=

+ =

E D

r r

5 06/04/2014

WACC

Taxes and WACC

After-tax cost of debt =r

D

(1 T

C

)

The WACC adjusted for tax savings due to interest payments is

For the above example, if the tax rate is 34%, the after-tax cost of debt

is

r

D

(1 T

C

) = 15%(1 34%) = 9.9%, and

E C D asset

r

V

E

T r

V

D

r + = = ) 1 ( WACC

% 96 . 18 % 25

100

60

%) 34 1 %( 15

100

40

WACC = + =

6 06/04/2014

WACC: an example

Suppose a firm has both a current and target debt-equity ratio of 0.6, a cost

of debt of 15.15%, and a cost of equity of 20%. The company tax rate is

34%.

The firm is considering a project. The project requires an initial investment of

$50 million and is expected to generate a perpetual cash flow of $8.125

mllllon a year. lf Lhe pro[ecL has Lhe same rlsk as Lhe flrms exlsLlng

business, should the firm go ahead with it?

Because D/E = 0.6, so (D+E)/E = 1.6

E/V = 1/1.6 = 0.625 (equity-value ratio)

D/V = 1- E/V = 1-0.625 = 0.375 (debt-to-value ratio)

NPV =8.125/16.25% - 50 = 0

% 25 . 16 2 . 0 625 . 0 %) 34 1 ( % 15 . 15 375 . 0 ) 1 ( WACC = + = + =

E C D

r

V

E

T r

V

D

7 06/04/2014

WACC

WACC: an extension

Suppose the firm also has outstanding preferred stock. Let

P denote the value of these preferred stocks and V = D + E

+ P

If a firm has issued 3 types of securities: debt, preferred stock

and common stock, and r

D

=6%, r

E

=18%, r

P

=12%. D=$4, P=$2,

E=$6, T

C

= 35%. So, V = D + P + E = 4+2+6=12

P E C D

r

V

P

r

V

E

T r

V

D

+ + = ) 1 ( WACC

% 3 . 12 % 12

12

2

18 . 0

12

6

%) 35 1 ( % 6

12

4

) 1 ( WACC

= + + =

+ + =

P E C D

r

V

P

r

V

E

T r

V

D

8 06/04/2014

Calculating required rates of return: The expected

return on bonds (YTM)

The YTM is defined as the interest rate that

makes Lhe presenL value of Lhe bonds

payments equal to its price.

Example: If you bought a 3-year bond with a

coupon rate of 10% for $1,136.16, the YTM, r,

satisfies the following equation:

Solve for r, r = 5%

( ) ( )

3 2

1

000 , 1 100

1

100

1

100

16 . 136 , 1

r r r +

+

+

+

+

+

=

9 06/04/2014

Calculating required rates of return: The

expected return on common stock

Estimates based on CAPM

Expected return on stock = risk-free raLe + sLocks

beta expected market risk premium.

Dividend discount model (DDM)

We can rearrange this formula to provide an

estimate of r

E

g r

DIV

P

E

=

1

g

P

DIV

r

E

+ =

1

10 06/04/2014

Calculating required rates of return: The expected return

on preferred stock

Preferred stock that pays a fixed dividend can be

valued from the perpetuity formula:

Therefore, the expected rate of return on preferred

stock can be obtained by rearranging the formula to

P

preferred

r

DIV

P =

preferred

P

P

DIV

r =

11 06/04/2014

Measuring capital Structure

Capital sLrucLure ls Lhe flrms mlx of flnanclng.

Example. Suppose a flrms book values of debL

and equity are follows:

Bank debt $200 million

Long-term bonds 200 (coupon rate 8%, 12 year)

Common stock 100 (100 million outstanding shares of stock $1 per share)

Retained earnings 300

Total 800

12 06/04/2014

Measuring capital structure

The differences between market values and book values for bank

loans are negligible, because the interest rate on bank loans usually

changes with market interest rate.

1he markeL value of a companys bonds ls Lhe v of all coupons and

par value discounted at the current interest rate.

For these bonds, if the interest rates have risen to 9% since bonds

were originally issued, we can calculate the value of the bonds.

There are 12 payments of $0.08 200 =$16 million, and then

repayment of $200 million face value at the end of 12 years. So,

( ) ( )

7 . 185 $

% 9 1

200 16

% 9 1

16

% 9 1

16

12 2

=

+

+

+ +

+

+

+

= A PV

13 06/04/2014

Measuring capital structure

1he markeL value of a companys equlLy ls Lhe

market price per share multiplied by the

number of shares outstanding.

If Lhe flrms sLock ls $12 per share, Lhen Lhe markeL value of

equity = $12 100 million = $1200 million.

Bank debt $200 million

Long-term bonds 185.7

Common stock 1200

Total 1585.7

14 06/04/2014

Capital structure and WACC when

there are no corporate taxes

Suppose a firm has the following market-value balance sheet:

If the r

D

= 8% and r

E

= 20%,

If the firm changes its capital structure as follows

Will WACC change? No

Assets Liabilities and Equity

Debt: $40

Equity: $60

Total $100 100

% 2 . 15 % 20

100

60

% 8

100

40

= + = WACC

Assets Liabilities and Equity

Debt: $50

Equity: $50

Total $100 100

15 06/04/2014

Asset beta and equity beta (no taxes)

The asset beta is the weighted average of the

equity and debt betas,

If we assume that debt beta is zero, then

This formula shows the two sources of risk: the

business risk, measured by the asset beta, and

the financial risk, reflecting the impact of

leverage, dependent on the debt-equity ratio.

Increasing leverage raises the debt-equity ratio

and increases the financial risk to shareholders.

16

equity debt assets

V

E

V

D

| | | + =

|

\

|

+ =

E

D

assets equity

1 | |

06/04/2014

Capital structure and WACC when

there are corporate taxes

If there are taxes, changes in the capital

structure will affect WACC.

Changes in the capital structure will change the

interest payments and will affect taxes.

An increase in debt-to-asset ratio increases the

flrms cash flow, lL wlll make Lhe debL and equlLy

riskier. As a result, r

D

and r

E

will increase.

Changing the capital structure might affect beta.

Beta of firm is the weighted average of the beta

of its debt and equity.

17 06/04/2014

Flotation costs and WACC

Flotation costs are the costs of issuing new

securities to the public.

Flotation costs should be treated as negative

cash flows, because the cost of capital

depends on the interest rates, taxes, and the

risk of the project.

So floLaLlon cosLs do noL affecL Lhe pro[ecLs

cost of capital.

18 06/04/2014

Interpreting the Weighted Average

Cost of Capital

When ?ou Can and CanL use WACC

The WACC is the rate of return that the firm must

expect to earn on its average-risk investments in

order to compensate its investors.

Thus, WACC may be used to value new assets

that:

Have the same risk as the old ones.

Will support the same ratio of debt as the firm itself.

19 06/04/2014

Valuing Entire Business

In order to value the business, we take the free cash

flows up to the year it is available, calculate the horizon

value, and then discount these all by the WACC of the

company to get its market value.

PVH = FCFH(1+g)/(WACC-g)

Free cash flow: cash flow that is not required for investment in

fixed assets or working capital and is therefore available to

investors.

20 06/04/2014

Valuing Entire Business

Calculating the free cash flow:

21 06/04/2014

Valuing Entire Business

Estimation of WACC

Capital structure: D/V =60%

Required rate of return on equity = 12%

Cost of debt = 5%

WACC = 40% 12% + 60% 5% (1-35%) =

6.75%

22 06/04/2014

Valuing Entire Business

Horizon value = FCF in year 6/(r-g) =

79.5/(6.75%-5%)=$2,271.4 thousand

PV of the business = 73.6/1.085

87.1/1.0675^2 -102.9/1.0675^3 -

34.1/1.0675^4 +

40.2/1.0675^5+2,271.4/1.0675^5 = $3562.34

thousand

23 06/04/2014

CH. 14: Corporate Financing

1

Common stock: Terminology

The term common stock (or, common shares) means different things to

different people, but is usually applied to stock that has no special

preference either in dividends or bankruptcy.

Owners of common stock in a firm are referred to as shareholders or

stockholders.

There can be a stated value on each stock certificate called the par value.

The difference between issue price and par value of stock is called

additional paid-in capital, or capital surplus, contributed surplus or paid-in

surplus.

Shares that have been issued by the company and are held by investors

are called outstanding shares.

The maximum number of shares that can be issued is known as the

authorized share capital.

Treasury stock: in the U.S., when a company repurchases some of its

shares, it can continue to hold them as its own stock. These shares appear

in the balance sheet as treasury stock.

2

Common stock: characteristics of

dividends

Unless a dividend is declared by the board of directors of a

corporation it is not a liability of the corporation. A

corporation cannot default on an undeclared dividend.

Dividends are not a business expense and are not

deductible for corporate tax purpose.

Dividends received by individual shareholders are taxed at

reduced rates. Dividend income is generally not taxed when

received by Canadian corporations.

The earnings that are not paid out as dividends are called

retained earnings. The sum of accumulated retained

earnings, contributed surplus, common shares, and

adjustments to equity is known as net common equity of

the firm.

3

An example

1he followlng ls Lhe book value of common shareholders equlLy

of a Canadian firm (in millions):

Common shares $10,000

Contributed surplus 1,000

Retained earnings 5,000

Foreign currency exchange adjustments 500

(the currency transaction gains

from Lhe flrms forelgn operaLlons)

Net common equity 16,500

lf Lhe flrms ouLsLandlng shares are 1,000, Lhe book value per share

=16,500/1,000 = $16.5/per share

4

An example

Now suppose the firm has profitable investment

opportunities and decides to sell 1,000 shares of new

stock to raise the necessary funding. The issuing price is

$20 per share. Now new net common equity account is

Common shares $30,000

Contributed surplus 1,000

Retained earnings 5,000

Foreign currency exchange adjustments 500

Net common equity 36,500

Book value per share = 36,500/2,000 =$18.25/share

If the current stock price is $20/share, then the total market

value of common stock is 2,000 $20 =$40,000 thousands

=$40 million, which is higher than the book value.

5

Common stock

Book Value vs Market Value

Book value is a backward-looking measure.

It tells you how much capital the firm raised from its shareholders

in the past.

Market value is forward looking.

It is a measure of the value investors place on the shares today.

It depends on the future dividends which shareholders expect to

receive.

The market-to-book value ratio is usually greater than

one because the firm has invested projects with a

positive NPV. The firm will be able to generate earnings

that exceed initial cost.

6

Shareholders rlghL

Shareholders elect directors who, in turn, hire management to carry

out their directives. Shareholders, therefore, control the

corporation through the right to vote on appointments to the board

of directors.

The mechanism for electing directors differs across companies.

In the case of majority voting, each director is voted on separately (in

a separate election), and shareholders can cast one vote for each

share they own.

In the case of cumulative voting, the directors are voted on jointly (at

once); therefore, all the votes one shareholder is allowed to cast can

be cast for one candidate for the board of directors.

Proxy voting: Shareholders can either vote in person or appoint a

proxy to vote.

If shareholders are not satisfied with management or with the

corporate governance of the firm, an outside group of shareholders

can try to obtain as many votes as possible via proxy. They can vote to

replace managemenL or change Lhe companys governance. 1hls ls

called proxy contest, or proxy battle, which are often led by large

pension funds.

7

Voting mechanisms: an example

Suppose that one firm has two shareholders: A and B. A has

25 shares and B has 75 shares. Both want to be on the

board of directors. Let us assume that there are 4 directors

to be elected.

Under majority voting, A can cast a maximum of 25 votes for

each candidate and B can cast a maximum of 75 votes for

each. As a consequence, B will elect all of the candidates.

Under the cumulative voting, A has a total of 25 4 =100

votes, B has a total of 75 4 = 300 votes. If A gives all his

votes to himself, he is assumed of a directorship. It is not

possible for B to divide 300 votes among four candidates in

such a way Lo preclude As elecLlon Lo Lhe board.

8

Corporate Governance

Although shareholders own the company, they usually do not

manage it. This principal of separation of ownership and

control of a firm is prevalent around the world.

Separation of ownership and management creates a potential

conflict between the shareholders (owners) and their agents

(the managers).

Several mechanisms have evolved to mitigate this conflict:

The Board oversees management and can fire them.

Management remuneration can be tied to performance.

Poorly performing firms may be taken over and the managers

replaced by a new team.

Classes of stock

Many firms have more than one class of common stock.

They differ in their right to vote or receive dividends. They

are called class A, Class B, etc. Often, the classes are

created with unequal voting rights. The class B shares could

have limited voting rights. For instance, class A shares could

carry 10 votes per share, while class B shares carry only one

vote per share.

Common shares without full voting rights are called

restricted shares.

Restricted shares could be non-voting, which means they have

no votes.

They could be subordinate-voting, which means they have fewer

votes per share than another class of common shares.

Multiple voting shares carry multiple votes.

10

Preferred stock

Preferred stocks have preference over common stocks in the

payment of dividends and in the distribution of corporation assets

in the event of liquidation.

Preference means that holders of preferred shares must receive a

dividend before holders of common shares are entitled to anything. If

the firm goes into bankruptcy, preferred shareholders rank behind all

creditors but ahead of common shareholders. Preferred shares are a

form of equity from legal, tax, and regulatory standpoints; however,

holders of preferred shares often have no voting privileges.

Like debt, most preferred stock promises a series of fixed payments

to the investors and in general the dividends are paid in full and on

time. But preferred dividends are not like interests on bonds. The

board of directors may decide not to pay the dividends on preferred

stocks.

The sum of common equity and preferred stock is known as net

worth.

11

Types of preferred shares

Cumulative preferred shares: If the dividends are not paid in a particular year, they

will be in arrears. Usually, both the cumulative dividends plus current dividends

must be paid before the common stock shares are receiving anything.

Non-cumulative preferred shares: If a preferred share is non-cumulative then

investors are only entitled to the payment of dividend if the board declares a

dividend. If the preferred dividend is not paid, it does not go into arrears, and is

lost forever. Unpaid preferred dividends are not debts of the firm. The board of

directors can defer preferred dividends indefinitely.

Redeemable preferred shares: A company has the right to repurchase these shares

from the shareholders at a pre-specified price. This price is known as the call price.

Retractable preferred shares: The investor can force the company to buy back

his/her shares at a specified date.

Convertible preferred shares: They may be converted into another type of security,

usually common shares.

In general the yields on preferred shares are lower than the interest rates of debt.

Dividend income is not taxed when received by Canadian corporations and is taxed

at reduced rates when received by individuals.

12

Preferred stock vs bank loan

x?Z co. pays no Lax. A banks marglnal Lax raLe ls

35%. Interest rate on the bank loan is 8%, while

preferred dividend yield is 6%.

lrom Lhe banks polnL of vlew:

after-tax return on the bank loan is 8%(1-35%)=5.2%

Return on preferred shares = 6%

From the Cos point of view:

after-tax costs of the bank loan is 8%

costs of funds if selling preferred shares = 6%

13

Corporate long-term debt:

terminology

When companies borrow money, they promise to make

regular interest payments and to repay the principal.

The person or firm making the loan is called a creditor or a

lender.

The company borrowing the money is called debtor or

borrower.

The amount owed the creditor is a liability of the company.

However, it is a liability of limited value. The corporation

can legally default at any time on its liability and hand over

the assets to the creditors. Clearly, the company will choose

bankruptcy only if the value of the assets is less than the

amount of the debt.

14

Characteristic of debt

Debt is not an ownership interest in the firm.

Creditors do not usually have voting power.

1he companys paymenLs of lnLeresL are regarded

as a cost and are fully tax deductible.

Unpaid debt is a liability of the firm. If it is not

paid, the creditors can legally claim the assets of

the firm. This action may result in liquidation or

bankruptcy. Thus, one of the costs of issuing debt

is the possibility of financial failure, which does

not arise when equity is issued.

15

Corporate long-term debt: Interest

rate

The interest payment or coupon on most long-

term loans is fixed at the time of issue.

Most loans from a bank and some long-term

loans may have a floating interest rate. The

interest rate is often reset according to a

benchmark rate regularly.

Prime Rate: Benchmark interest rate charged by banks

to large customers with good to excellent credit.

London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR): Rate at which

international banks lend to each other.

16

Corporate long-term debt: Maturity

Typically, debt securities are called notes,

debentures, or bonds.

In legal language, a debenture is an unsecured

corporate debt.

A bond is secured by a mortgage on the corporate

property.

A note usually refers to a short-term obligation.

Debentures and bonds are long-term debt. Debt due

in less than a year is called short-term. Long-term

debt is any debt repayable more than one year from

the date of issue.

17

Corporate debt

Investment Grade: Bonds rated above Baa or BBB .

Junk Bond: Bond with a rating below Baa or BBB.

Eurodollars: Dollars held on deposit in banks

outside the US.

Eurobond: Bond that is denominated in the

currency of the issuer but issued to investors in

other countries.

Foreign bond: Bond issued in another country and

denominated in the currency of that country.

18

Corporate long-term debt: Repayment

Bonds can be repaid at maturity or earlier through the use of a

sinking fund.

A sinking fund is the fund established to retire debt before maturity.

Each year the firm puts aside a sum of cash into a sinking fund that is

then used to buy back the bonds.

A callable bond is the bond that can be repurchased by the firm

before maturity at a pre-specified call price.

The option to buy back the bond at a pre-specified price before

maturity is valuable to the issuer. If interest rates decline and bond

prices rise, the issuer may repay the bonds at the pre-specified call

price, and borrow the money back at a lower rate of interest.

On the other hand, the call provision comes at the expense of

bondholders because lL llmlLs lnvesLors caplLal galn poLenLlal.

So, other things being equal, the price of a callable bond should be

lower than the bond without call provisions.

19

Seniority

In general terms, seniority indicates preference

in position over other lenders. Some debt is

subordinated. In the event of default, holders

of subordinated debt get in line behind the

flrms general credlLors. 1hls means Lhe

subordinated lenders will be paid off only

after all senior creditors are satisfied.

20

Corporate long-term debt: Security

Secured Debt: Debt that has first claim on specified

collateral in the event of default.

When companies borrow, they may set aside

certain assets as security for the loan. The assets

are termed collateral and the debt is said to be

secured. In the event of default, the secured

lenders have the first claim on the collateral;

unsecured lenders have a general claim on the

resL of Lhe flrms asseLs buL only a [unlor clalm on

the collateral.

21

Corporate long-term debt: Public

versus private placements

Publicly issued bonds are sold to anyone who

wishes to buy and once they have been issued

they can be freely traded in the markets.

In a private placement, the bonds are sold to a

limited number of investors without a public

offering.

22

Corporate long-term debt: Protective

covenant

To ensure that the company will use the

money borrowed well and not take

unreasonable risks. Lenders usually impose a

number of conditions on the company. These

restrictions are called protective covenants.

For example, limitations are placed on the amount

of dividends a company may pay; the firm cannot

issue additional long-term debt; the firm may not

sell or lease its major assets without approval

given by the lender.

23

Convertible securities

Warrant: Companies sometimes issue bonds with provisions that

allow the bondholders to buy shares from the company at a

stipulated price before a set date. So the warrant is valuable to

bondholders.

Convertible bonds: A convertible bond gives its owner the option to

exchange the bond for a pre-specified number of common shares.

Obviously, these options are valuable to bondholders.

The owner of a convertible bond owns a bond and a call option on

Lhe flrms sLock, so does Lhe owner of a package of a bond and a

warrant. However, there are differences with the most important

belng LhaL a converLlble bonds owner musL glve up Lhe bond Lo

exercise the option. The owner of a package of bonds and warrants

exercises the warrants for cash and keeps the bond.

24

Patterns of corporate financing

Funds for investment may be raised from external (debt or equity

security issues) or internal sources, such as cash flow from

operations.

Internal financing is defined as net income plus depreciation minus

dividends.

The first form of financing used by firms for positive NPV projects is

internally generated cash flows.

When a firm has insufficient cash flow from internal sources, it sells

off part of its investment in marketable securities.

As a last resort, a firm will use externally generated cash flow. First

debt is used and common stock is used last.

Reasons: (1) managers do not wish to be critically assessed or

monitored by the financial markets and financial institutions. (2)

The cost of financing externally is avoided when internally

generated funds are used.

25

Patterns of Corporate Financing

Sources of Financing for Non-financial Private

Corporations (1988-2006):

26

CH. 15: Venture Capital, IPOs and

Seasoned Offerings

1

The initial public offering

IPO: A flrms flrsL offerlng of sLock Lo Lhe general publlc ls

called an initial public offering and the firm is said to go

public.

Stock market can be either organized exchanges with centralized

locations or over-the-counter market consisting of a network of

security dealers who trade with each other over the phone and

through electronic networks.

The listing requirements : the minimum amount of net assets,

earnings, cash flow, adequate working capital and an

appropriate capital structure.

Before any stock can be sold to the public, the firm must satisfy

the requirements of provincial securities laws and regulations.

Regulations of the securities market in Canada are carried out

by provincial commissions and through provincial securities

acts. In the US, regulation is handled by a federal body, the

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The stock to be sold

to public may have to be registered with an appropriate

securities commission.

2

The Basic Procedure for an IPO

The firm must prepare and distribute copies of preliminary

prospectus to (Ontario Securities Commission) OSC and to

potential investors.

Prospectus is a formal summary that provides information on an

issue of securities.

The preliminary prospectus is sometimes called a red herring, in

part because bold red letters are printed on the cover warning

that OSC has neither approved nor disapproved of the

securities.

The securities commission studies the preliminary

prospectus and notifies the company of any changes

required.

Once the revised, formal prospectus meets with the

securities commlsslons approval, a prlce ls deLermlned and

a full-fledged selling effort gets under way.

3

The initial public offering

One important advantage of going public is that public

firms have greater access to new capital once their

shares are traded on secondary markets. Further,

publicly traded firms must meet OSC and other

disclosure requirements that reduce information risk

for potential investors. In addition, going public makes

lL posslble for Lhe flrms prlnclpal owners Lo sell some

of their shares and diversify their personal portfolios

while retaining control of the company.

Going public also has disadvantages. Public firms are

subject to stricter disclosure and other potentially

costly regulatory requirements.

4

The initial public offering: Underwriting

Underwriters are lnvesLmenL dealers LhaL acL as flnanclal mldwlves" Lo a new

issue. They perform the following services for corporate issues ( they play a triple

role):

Providing the company with procedural and financial advice

Buying the new securities

Selling the new securities

A small IPO may have only one underwriter, but for large issues a group of

underwriters called a syndicate or banking group will usually be formed to handle

the sale. Syndication helps to market and distribute the issue more widely and also

to share its risks. In a syndicate, one or more underwriters arrange or co-manage

the offering.

Typically, the underwriter buys the securities for less than the offering price and

accepts the risk of not being able to sell them. The difference between the

underwrlLers buylng prlce and Lhe offerlng prlce ls called Lhe spread.

In a typical underwriting arrangement, which is called a firm commitment, the

underwriters buy the securities from the issuing firm and re-sell them to the public

for the purchase price plus an underwriting spread. In this case, the underwriters

accept the risk of not being able to sell the securities.

Another type of underwriting is on a best efforts basis. In this case, the

underwriter agrees to sell as much of the issue as possible but does not guarantee

the sale of the entire issue. This form of underwriting is more common with IPOs.

The fees tend to be less in a best-effort distribution.

5

The Underwriters

Canadas Lop underwrlLers for equlLy and debL

in 2007.

The initial public offering: Pricing IPOs

The issuing firm faces a potential cost if the offering price is

set too high or too low.

If the issue is priced too high, it may be unsuccessful and have

to be withdrawn.

If Lhe lssue ls prlced below Lhe Lrue markeL prlce, Lhe lssuers

existing shareholders will experience an opportunity loss.

The managers of the firm are eager to secure the highest

possible price for their stock.

The underwriters typically try to underprice the IPO, as

they argue that underpricing is needed to attract investors

to buy stock and to reduce the cost of marketing the issue

to customers. So, generally the stock price increases

substantially from the issue price in the days following an

issue.

7

The initial public offering: underpricing

A firm has 2 million shares outstanding, which are owned by

Lhe flrms founders. now Lhe flrm decldes Lo go publlc and

issue a further 1 million shares to investors at $50. On the

first day of trading, the share price jumps to $80.

The total market capitalization of the firm is 3 $80 =$240

million.

The value of Lhe founders shares ls equal Lo Lhe value of Lhe

firm less the value of shares that have been sold to the public,

i.e., $240 - $ 80 = $160.

If the price were at $80/share, it would only need to issue

0.625 million shares to raise the $50 million. In this case,

the share price will be $240/2.625 =$91.43. so the value of

Lhe founders share would be 240 240/2.625 0.625 =

240 57.14 = $182.86

8

The initial public offering: The wlnners

curse

Underpricing does not mean that anyone can become wealthy by

buying stock in IPOs.

When the price of an issue is too low, the issue is often

oversubscribed. This means investors will not be able to buy all of

the shares they want and the underwriters will allocate the shares

among investors. The average investor will find it difficult to get

shares in an oversubscribed offering because underwriters will not

have enough shares to go around.

When the issue is overpriced, other investors are unlikely to want it

and the underwriters will be only too delighted to sell it to you.

1hls ls called Lhe wlnners curse, and lL explalns much of Lhe reason

why IPOs have such a large average return. Unless you know the

true value of every IPO, you cannot earn an abnormal return by

buying shares in IPOs.

9

The initial public offering: The costs of

IPOs

Flotation Costs: The costs incurred when a firm issues

new securities to the public. It includes commissions,

legal, accounting and other administrative costs.

Costs of IPOs

The spread. The underwriting spread consists of direct fees

by the issuer to the underwriting syndicate.

Other direct expenses. These are direct costs incurred by

the issue that are not part of the compensation to

underwriters. These costs include filing fees, legal fees and

taxes, the costs of management time spent working on the

new issue.

Underpricing. For IPOs losses arise from selling the stock

below the correct value.

10

The initial public offering: The costs of

IPOs

For example, a firm went public last month. The underwriters acquired

a total of 100 million shares for $50 each and sold them to the

publlc aL an offerlng prlce of $33. 8y Lhe end of Lhe flrsL days

Lradlng, Lhe flrms sLock prlce had rlsen Lo $70. 1he flrm also pald a

total of $10 million in legal fees and other costs. Let us see the total

costs of this IPO.

Underwriting spread = 100 (55 50) = $500 million

Other direct expenses = $10 million

The cost of underpricing = 100 (70 55) = $1500 million

So, total cost = 500 + 10 + 1500 = $2010 million

Total market value of the issue shares = 100 70 = $7000 million

Total cost as a percentage of gross proceeds for the company is

2010/7000 = 28.7%

11

Rights issues and general cash offers

An issue of additional stock by a company

whose stock already is publicly traded is called

a seasoned offering.

The stock may be offered only to existing

shareholders, called a rights issue, or

sold to the general public, called a general cash

offer.

12

Rights issues

In a rights issue, shareholders would be able to purchase additional

shares at a price below current market price. In other words, in a

rights issue, the company offers the shareholders the right to buy a

specified number of new shares at a specified price within a

specified time, after which time the rights are said to expire.

Shareholders get one right for each share of stock they own. The

terms of the rights offering are evidenced by certificates known as

rights. Such rights are often traded on securities exchanges or over-

the-counter.

To execute a rights offering, the financial manager of a firm must

answer the following questions:

What price should the existing shareholders be allowed to pay for a

share of new stock?

How many rights will be required to purchase one share of stock?

What effect will the rights offering have on the price of the stock?

13

Rights issues: Subscription price

In a rights offering, the subscription price is the

price that existing shareholders are allowed to

pay for a share of stock.

A rational shareholder will only subscribe to the

rights offering if the subscription price is below

Lhe markeL prlce of Lhe sLock on Lhe offers

expiration date.

So, the subscription price is set below the market

price to ensure the rights offering will succeed. In

practice, the subscription price is typically 20 to 25%

below the prevailing stock price.

14

Rights issues: Number of rights needed

to purchase a share

Number of new shares = funds to be raised/subscription price

Number of rights needed to buy one share = number of old

shares/number of new shares

For example, suppose a firm has a million shares outstanding, selling at $20 a

share. To finance a planned expansion, the firm intends to raise $5 million

of new equity funds by a rights offering. If the subscription price is set at

$10 per share, how many new shares will be issued? How many rights are

needed to buy one share? What will be the stock price after the rights

issue?

Number of new shares = $5,000,000/$10 = 500,000 shares

Number of rights needed to buy one share = 1,000,000/500,000 = 2 rights

So, a shareholder will need to give up two rights and $10 to receive a

share of new stock. So the stock price after the issue = (2 20 + 10)/3 =

16.67

After the rights issue, the firm will have a total of 1.5 million shares

outstanding (1+0.5), and the total value of the firm will be: 1 20 + 5 =$

25 million. So, the stock price will be =25/1.5 = $16.67/ per share.

15

Rights issues: The value of a right

Note that the shareholder needs two rights to buy one share at

$10, however, the market price of the share after the rights issue

(the ex-rights price) is $16.67.

Subscription price + # of rights value of a right = ex-rights price

Therefore, theoretically, the value of a right is worth

It can also be calculate as follows

Rights-on price of shares = ex-rights price + value of a right

335 . 3

2

10 67 . 16

share a buy to needed rights of #

price on subscripti - price rights - ex

right one of value

335 . 3

1 2

10 20

1 share a buy to needed rights of #

price on subscripti - price on - rights

right one of value

16

Rights issues: an example

Assume a firm has proposed a rights offering. The stock currently sells for $40 per

share. Under the terms of the offer, shareholders will be allowed to buy one new

share for every five that they own at the price of $25 per share. What is the value

of a right and what is the ex-rights price?

Value of one right = (40-25)/(5+1) = 2.5

Ex-right price = rights-on price value of one right = $40 2.5 = $37.5/share

Shareholders can exercise their rights or sell them. In either case, the shareholder

will not win or lose by the rights offering.

For the above example, suppose the investor hold 5 ex-rights shares with a total value

of $200. If he/she exercises the right, he/she ends up with 6 shares worth a total of

$223. ln oLher words, by spendlng $23, Lhe lnvesLors holdlng lncreases ln value by

$25.

On the other hand, if the shareholder sells the five rights for $2.5 each. The cash flow

will be:

Share held = 5 37.5 = 187.5

Rights sold = 5 2.5 = 12.5

Total =$200

17

Rights Issues

Example

ABC Corp currently has 9 million shares outstanding. The

market price is $15 per share. ABC decides to raise

additional funds via a 1 for 3 rights offer at $12 per share.

If we assume 100% subscription, what is the value of each

right?

Current Market Value = 9 mil $15 = $135 mil

Total Shares = 9 mil + 3 mil = 12 mil

Amount of new funds = 3 mil $12 = $36 mil

New Share Price = (135+ 36) / 12 = $14.25 per share

Value of a Right = Rights-on price Ex-rights price

= 15 - 14.25 = $0.75

Rights issues: Ex-rights

The standard procedure for issuing rights is similar to that

for paying a dividend.

It beglns wlLh Lhe flrms seLLlng holder-of-record date. This

ls Lhe daLe on whlch shareholders appearlng on companys

records are entitled to receive the stock rights.

Following the stock exchange rules, the stock will usually go

ex-rights 4 trading days before the holder-of-record date.

If the stock is sold before the ex-rights date--- its value will

be rights on, with rights, cum rights--- the new owner will

receive the rights.

If the stock is sold on or after the ex-rights date, the buyer

will no longer be entitled to the rights.

19

Rights issues: The underwriting

arrangement

Rights offerings are typically arranged using a standby

underwriting. In a standby underwriting, the issuer

makes a rights offering, and the underwriter makes a

firm commitment to purchase any unsubscribed

shares. The underwriters usually get a standby fee.

Standby underwriting protects the firm against under

subscription.

Through a rights offering, a company could hope to

save on issuing and underwriting expenses. Also,

shareholders do not run a risk of dilution of their

proportional shareholding and are able to retain their

voLlng poslLlon on companys ma[or buslness declslons.

20

General cash offers

After IPO, firms can raise money by issuing securities to the general public.

These are called general cash offers. In a general cash offer, the procedure

is the same as that in an IPO. This means that the issue must be registered

in compliance with regulations of relevant provincial commissions. This

issue is then sold to an underwriter (or syndicate) who, in turn, offers the

securities to the public.

In a bought deal, the issuer sells the entire issue to one investment dealer

or to a group that then attempts to resell it. This form of underwriting is

often used by large, well-known companies for their seasoned equity

issues. As in firm commitment underwriting, the investment dealer

assumes all the price risk.

To llmlL Lhe underwrlLers rlsk, many underwrlLlng agreements may

contain a market-out clause, which can enable the underwriter to

terminate the underwriting agreement without penalty under

extraordinary circumstances or if the state of the financial market is not

deemed good for the security issue.

Like IPOs, costs of the general offer include underwriting spread,

administrative costs and underpicing. In addition, there is another type of

cost; that is, abnormal returns, arising from the market reaction to stock

issues.

21

Market reaction to stock issues

Statistics show that the price of the stock drops on average by 3% on the

announcement of a new issue of common stock. This represents losses of

Lhe markeL value of Lhe flrms equlLy.

Example, a firm just issued $250 million of equity which caused its stock price

Lo drop by 3. CalculaLe Lhe loss ln value of Lhe flrms equlLy glven LhaL lLs

market value of equity was $1 billion before the new issue.

1 3% = $30 million, and 30/250 = 12% of the amount of money raised.

Reasons:

Does adding more shares depress stock prices below their true value? No.

One possible reason for this strange result is that the stock issue could be a

signal to investors that management feels the stock is overpriced by the

market. Investors can predict that managers are more likely to issue stock

when they think it is overvalued and therefore, they mark the price of the

stock down accordingly.

22

The private equity market

Venture capital : Equity capital provided to a promising new business is

called venture capital. Or, the money invested to finance a new firm is

called venture capital.

Venture capital is provided by specialized venture capital firms, financial and

investment institutions such as banks and pension funds, and government

agencies.

If you need very early stage financing for your new enterprise, you may seek

financing from an angel investor. Angels are wealthy individual investors in

early-stage ventures. Angels can play a critical role in the creation of new

ventures by making small-scale investments in local start-ups and early-stage

ventures.

Private placement: sale of securities to a limited number of investors

without a public offering.

When a firm makes a public offer, it must register the issue with the relevant

provincial commission. Private placement can avoid this costly process. So this

issue can be placed quickly and at a lower cost of financing.

The biggest drawback of privately placed securities is that the securities

cannot be easily resold. As a result, the yield demanded by investors will likely

be higher.

23

CH. 16: Debt policy

1

How Borrowing Affects Value in a Tax Free Economy

The value of a firm from two angles:

A flrms capital structure is the mix of debt and equity its financial

managers choose.

Does the choice of capital structure affect the value of a firm?

Assets

Liabilities and Stockholders Equity

Value of cash flows

from firms real

assets and operations

Market value of debt

Market value of equity

Value of Firm

Value of Firm

2

MMs proposlLlon l wlLh no taxes

Consider a firm that has no debt in its capital structure. In other

words, the firm is all-equity financed. This firm is called unlevered

company. Assume Lhe flrms asseLs are $1 mllllon. 1here are

100,000 shares outstanding. This implies that the price of each

share is $10. We further assume the firm pays all its operating

income as dividends to its shareholders and there are no corporate

taxes. So the financial structure of the firm can be summarized as

follows:

Debt 0

Equity $1 million

Total $1 million

Shares outstanding: 100,000

Price per share $10

3

MMs proposlLlon l wlLh no Laxes

Assume LhaL Lhe flrms reLurns Lo shareholders

under different economic conditions are given

as follows:

Slump Normal Boom

Operating income $75,000 $125,000 $175,000

Return on assets (ROA=income/assets) 7.5% 12.5% 17.5%

Earnings per share (EPS=income/100,000) 0.75 1.25 1.75

Return on equity (ROE = income/equity) 7.5% 12.5% 17.5%

4

MMs proposlLlon l wlLh no Laxes

Now, suppose the financial manager of the firm proposes to

issue $0.5 million of debt at an interest rate of 10% and to

use the proceeds to repurchase 50,000 shares.

This is called restructuring. The assets of the firm are not

affected; only the capital structure changes.

After the issuance of debt, the firm becomes levered.

1he flrms proposed flnanclal sLrucLure ls as follows:

Debt $500,000 million

Equity $500,000 million

Total $1 million

Shares outstanding: 50,000

Price per share $10

5

MMs proposlLlon l wlLh no Laxes

1he flrms reLurns Lo shareholders under dlfferenL

economic conditions are (operating income is the

same)

Is leverage beneficial?

Slump Normal Boom

Operating income $75,000 $125,000 $175,000

Return on assets (ROA=income/assets) 7.5% 12.5% 17.5%

Interest $50,000 $50,000 $50,000

Equity earnings $25,000 $75,000 $125,000

Earnings per share (EPS=equity income/50,000) 0.5 1.5 2.5

Return on equity (ROE =equity income/equity) 5% 15% 25%

6

MMs proposlLlon l wlLh no Laxes

In the case of current capital structure, consider the following

strategy

An investor borrows $10 at 10% from a bank.

Use the borrowed proceeds plus your own investment of $10 to buy 2

shares of the current unlevered equity at $10 per share.

The initial cost of this strategy = $10 2 -10 = $10.

The payoff of this strategy:

Slump Normal Boom

Earnings on two shares of the unlevered firm $1.5 $2.5 $3.5

Interest at 10% on $10 $1 $1 $1

Net Earnings 0.5 1.5 2.5

Return on $10 investment 5% 15% 25%

7

MMs proposlLlon l wlLh no Laxes

MM Assumptions:

CaplLal markeLs have Lo be well funcLlonlng".

Investors can borrow/lend on the same terms as firms.

Capital markets are efficient.

There are no taxes or costs of financial distress.

M&Ms proposlLlon l (debL lrrelevance proposlLlon):

The value of the firm must be unaffected by its

capital structure.

In other words, managers cannot increase firm value

by changing the mix of securities used to finance the

company .

8

Risk to equityholders rises with

leverage

From that example, we see that investors expected return

rlses afLer resLrucLurlng, buL MMs proposlLlon l Lells us LhaL

they are not better off. Why not?

The reason is that shareholders bear more risk.

Restructuring does not affect operating income regardless

of the state of the economy. So debt financing does not

affecL Lhe operaLlng rlsk, whlch ls Lhe rlsk ln flrms

operating income, but debt increases the uncertainty about

percentage stock returns. For example, in a slump the

return on equity drops by 10% if the firm issues debt (is

levered), but it only drops by 5% if the firm is all-equity

financed.

The risk to shareholders resulting from the use of debt is

called financial risk. so, debt finance increases financial risk.

9

How Borrowing Affects Value in a Tax Free Economy

How borrowing affects risk and return.

Even though the value of the firm remains unchanged,

shareholders of the levered firm face a higher risk and

therefore demand a higher return.

Firm Value:

All Equity Financing After Restructuring

$1 million

Debt:

Equity:

$500,000

$500,000

10

Financial Leverage and EPS

(2.00)

0.00

2.00

4.00

6.00

8.00

10.00

12.00

1,000 2,000 3,000

E

P

S

Debt

No Debt

Break-even

point

EBI in dollars, no taxes

Advantage to

debt

Disadvantage to

debt

EBIT

MMs proposlLlon II

Restructuring does noL change Lhe flrms operaLlng

earnings; it does not change the return on assets or the

flrms welghLed average cosL of caplLal.

Rearranging the above formula gives

This ls called MMs proposlLlon ll. lL says LhaL Lhe

requlred raLe of reLurn on equlLy lncreases as Lhe flrms

debt-equity ratio increases.

U E L E D asset

r r

V

E

r

V

D

r WACC

, ,

) (

, , , D U E U E L E

r r

E

D

r r

12

MMs proposlLlon ll: an example

For the unlevered firm:

For the levered firm:

% 5 . 12

000 , 000 , 1

000 , 125

,

asset U E

r r

% 15 %) 10 % 5 . 12 (

000 , 500

000 , 500

% 5 . 12 ) (

, , ,

D U E U E L E

r r

E

D

r r

13

Capital structure and corporate taxes: Interest tax shield

uppose Lhe flrms Lax raLe ls 33. LeL us see Lhe expecLed earnlngs for boLh Lhe

unlevered and the levered firms. Firm A: unlevered, D = 0, E = $1,000,000.

Firm B: D = 500,000, E = 500,000, T

C

= 35%, r

D

= 10%.

For the levered firm, the annual interest tax shield is 50,000 0.35 = $17,500

In general, annual interest tax shield = T

C

r

D

D, if debt is permanent. If the

tax shield is perpetual, the PV of tax shields is

PV of tax shields = .

A (zero debt) B (debt = $500,000)

Annual expected operating income (EBIT) $125,000 $125,000

Debt interest at 10% 0 50,000

Earnings before taxes (EBT) $125,000 75,000

Taxes (35%) $43,750 26,250

Earnings after taxes 81,250 48,750

Total income to both $81,250 98,750

Equitholders and debtholders difference $17,500

D T

r

D r T

C

D

D C

14

Value of the levered firm

Value of levered firm = value of all-equity firm

+ PV of interest tax shields = value of all-equity

firm + T

C

D

Or, V

L

= V

U

+ T

C

D

1hls ls MMs proposlLlon l under corporaLe Laxes.

The value of levered firm is positively related

to the amount of debt. By raising the debt-

equity ratio, the firm can lower its taxes and

thereby increase its total value.

15

MMs proposlLlon ll under corporaLe

taxes

MMs proposlLlon ll under no Laxes poslLs a poslLlve

relationship between the expected return on equity and

leverage. This result occurs because the risk of equity

increases with leverage. The same intuition also holds in a

world of corporate taxes. MMs proposlLlon ll wlLh corporaLe

taxes

Corporate taxes and WACC

16

) )( 1 (

, , , D U E C U E L E

r r T

E

D

r r

L E C D

r

V

E

T r

V

D

WACC

,

) 1 (

MM proposition II: an example

D = $500,000 and r

D

=10%, EBIT

L

=EBIT

U

= $125,000, T

C

=35%. Assume the cost

of capital if the firm were unlevered = 12.5% = r

E,U

Annual interest tax shields = T

C

r

D

D = 35% 10% 500,000 = $17,500

PV of the interest tax shields = T

C

D =35% 500,000 = $175,000

The value of unlevered firm V

U

=

The value of the levered firm V

L

= V

U

+ T

C

D = 650,000 + 175,000 =

825,000. Therefore, the value of equity of the levered firm is E = V

L

- D =

825,000 500,000 = 325,000.

Accordlng Lo MMs proposlLlon ll under corporaLe Laxes,

WACC

L

=

17

000 , 650 $

% 5 . 12

%) 35 1 ( 000 , 125 ) 1 (

asset

C

r

T EBIT

% 15 %) 10 % 5 . 12 %)( 35 1 (

000 , 325

000 , 500

% 5 . 12 ) )( 1 (

, , ,

D U E C U E L E

r r T

E

D

r r

% 85 . 9 % 15

000 , 825

000 , 325

% 10 %) 35 1 (

000 , 825

000 , 500

) 1 (

,

L E D C

r

V

E

r T

V

D

Costs of Financial Distress: Trade-off

theory

Debt provides tax benefits to the firm.

Debt puts pressure on the firm, because interest and principal

payments are obligations. If these obligations are not met, the firm

may risk some sort of financial distress. The ultimate distress is

bankruptcy. Financial distress is costly. Costs of financial distress

arise from bankruptcy or distorted business decisions before

bankruptcy.

Financial distress costs tend to offset the advantages to debt. The

overall value of the firm should be

Value of the levered firm = value of the all-equity financed firm + PV

of interest tax shields PV costs of financial distress

The Trade-Off Theory says that financial managers choose the level of

debL whlch wlll balance Lhe flrms lnLeresL Lax shlelds agalnsL lLs cosLs of

financial distress.

18

Trade-off Theory

Bankruptcy in Canada

Direct and indirect costs of financial distress

Direct costs

Legal fees: Courts and lawyers are involved throughout all the stages before

and during bankruptcy.

Administrative and accounting fees can substantially add to the total bill.

Indirect costs of bankruptcy reflect the difficulties of running a company while it is

going through bankruptcy.

Agency costs: When a firm has debt, conflicts of interest arise between

shareholders and bondholders, and shareholders are tempted to pursue

selfish strategies. These conflicts of interest impose agency costs on the firm.

Selfish strategies:

Incentive to take large risk. Firms near bankruptcy often take great chances,

because Lhey feel LhaL Lhey are playlng wlLh someone elses money. 1hey have

nothing to lose by taking great risks. If they lose the game, they have nothing

to lose. If they win the game, they may have more than enough assets to pay

off the debt, and receive the surplus.

Incentive toward underinvestment. Shareholders of a firm with a significant

probability of bankruptcy often find that new investment helps the

bondholders aL Lhe shareholders expense. 1he reason ls LhaL shareholders

contribute the full investment, but the shareholders and bondholders share

the benefits.

20

The pecking order theory

The pecking order theory of capital structure states that:

Firms prefer internal finance because these funds are raised

without sending any positive or negative signals.

If external finance is required, firms issue debt first, and issue

equity as a last resort.

The theory starts with the observation that managers know

more Lhan ouLslde lnvesLors abouL Lhe flrms value and

prospects. Therefore, investors find it difficult to value new

security issues, particularly issues of common stock.

Investors may interpret the announcement of a stock issue

as a pessimistic manager signal. That is why stock sales

announcements tend to drive stock prices down. Internal

finance avoids this problem. If external financing is

necessary, debt is the first choice.

21

The pecking-order model

The pecking order theory explains why the most profitable firms

generally borrow less, because Lhey donL need ouLslde money. Less

profitable firms issue debt because they do not have sufficient internal

funds for their capital investment and because debt is the first in the

pecking order for external finance.

The pecking-order model explains why firms hold vast cash and

marketable securities reserves.

A firm will sometimes forgo positive-NPV projects if accepting them

forces the firm to issue undervalued equity to new investors.

This in turn provides a rationale for firms to value financial slack.

Financial Slack means having cash, marketable securities, readily

saleable real assets and ready access to the debt markets or to bank

financing.

Financial slack permits firms to undertake projects that they might

decline if they had to issue new equity to invest.

22

CH. 18: Payout Policy

1

How dividends are paid: Cash

dividends

The term dividend usually refers to cash distributions of earnings.

Public companies usually pay regular cash dividends four times a year.

Sometimes firms pay a regular cash dividend and an extra cash dividend.

1he Lerm regular" lndlcaLes LhaL Lhe flrm expecLed Lo malnLaln Lhe

payment in the future.

The date on which the board of directors declares a payment of dividend

is called the declaration date.

Record date: This is the date on which shareholders appear on the

company records are entitled to receive the dividend.

In practice, stock exchanges fix a cut-off date, called ex-dividend date, 2

business days prior to the record date. All the shareholders are entitled to

receive the dividend if they purchased the stock before the ex-dividend

date. Before this date, the stock is said to trade cum-dividend, or with

dividend.

The payment date is the date on which the dividend cheques are mailed

to the investors. So the key dates for dividend payments

2

Chapter 16 -3

How dividends are paid: cash dividends

A company has declared a dividend with a payment date of June

30

th

. The date of record is Monday, June 6

th

.

In a world with neither taxes nor transaction costs, the stock price is

expected to fall by the amount of the dividend when the stock

goes ex".

2 3 4 5

6

Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon

1

Date of Record

Count back 2 business days

Ex-dividend Date

x x

Cum-dividend

Date

How dividends are paid: stock

dividends

Stock dividend: Distribution of additional shares, instead of

cash, Lo Lhe flrms shareholders.

A stock dividend is commonly expressed as a ratio. For example,

with a 100% stock dividend, a shareholder receives one new

share for every share owned. With a 5% stock dividend, a

shareholder receives one new share for every 20 shares

currently owned.

Stock dividends and stock prices: an example

Consider a flrms sLock LhaL ls selllng for $30 per share. lf Lhe

firm declares a 50% stock dividend which means the

shareholder will receive one additional share for every two

shares currently held, what is the price of a share of stock

after stock dividend?

Stock price =$100/3 = $33.3/share.

4

How Dividends are Paid

An example of stock dividend: XYZ Inc. has 2 million shares

currently outstanding at a price of $15 per share. The company

declares a 50% stock dividend. How many shares will be

outstanding after the dividend is paid? After the stock dividend

what is the new price per share and what is the new value of the

firm?

Additional shares issued = 2 mil 0.50 = 1 mil

New total shares outstanding = 2 mil + 1 mil = 3 mil

Old value = 2 mil $15 = $30 mil = New value

New price per share = $30 mil/3 mil = $10

5

How dividends are paid: stock splits

A stock dividend is very much like a stock split. In both cases, the shareholder is

given a fixed number of new shares for each share held. So they increase the

number of shares outstanding.

For example, in a two-for-one split, each shareholder receives one additional share of stock

for each share already held. So, a two-for-one stock split is equivalent to a 100% stock

dividend.

After Lhe sLock spllL, each share ls enLlLled Lo a smaller percenLage of Lhe flrms cash flow. o

the stock price should fall. If the managers of a firm whose stock is selling at $50 declare a

two-for-one stock split, the price of a share of stock should fall to about $25/share.

In a reverse split, the firm issues new shares in exchange for old shares, which

effectively reduces its number of outstanding shares.

For example, in a one-for-two reverse split, shareholders would exchange two shares held for

one new share.

Obviously, Lhe sLock prlce wlll lncrease afLer a reverse spllL. lf a flrms sLock ls selllng aL $30 per

share, after a one-for-two reverse split, the stock price should be $100 per share.

By doing this, the firm wishes to bring the share price to a more acceptable trading

range and increases its market participation and improve its liquidity.

6

Stock splits: an example

Home electronics has one million shares of common stock

outstanding. Its EPS is $7.5, and its P/E is 12. In order to

bring the stock price back into its optimal trading range, the

company declares a 5-for-4 stock split.

How many shares of common stock will be outstanding

after the split?

What will be the new EPS

How far will the share price fall as a result of the split?

Number of new shares = number of old shares split ratio

= 1,000,000 5/4 = 1,250,000 shares.

Total earnings = 1,000,000 7.5 =$7,500,000. EPS =

7,500,000/1,250,000 =$6/share.

The old price = 7.5 12 = 90. The new price = old price/split

ratio = 90/(5/4) = $72/share.

7

How dividends are paid: Share

repurchases

Share repurchase: Firm buys back stock from

its shareholders.

A share repurchase is similar to a cash

dividend.

Recently, share repurchases have become an

important way of distributing earnings to

shareholders.

8

Share repurchases vs cash dividends

To see why a share repurchase is similar to a dividend,

consider the following example

Assets liabilities and shareholders equity

A. Original balance sheet

Cash $150,000 debt $0

Other assets $850,000 equity: $1,000,000

Total $1,000,000 $1,000,000

Shares outstanding = 100,000, price = $10/share

B. After cash dividend ($100,000)

Cash $50,000 debt $0

Other assets $850,000 equity $900,000

Total $900,000 $900,000

Shares outstanding = 100,000, price = $9/share

C. After stock repurchase ($100,000)

Cash $50,000 debt $0

Other assets $850,000 equity $900,000

Total $900,000 $900,000

Shares outstanding = 90,000, price = $10/share

9

Share repurchases vs cash dividends

now, suppose you have 1,000 shares of Lhe flrms

stock, which are worth $10,000.

If the firm pays out $100,000 as a cash dividend,

shareholders will receive $1 per share. Therefore, after

the cash dividend, you will receive $1,000 in cash, and

you still own 1000 shares of the stock, which are worth

only $9,000.

If the firm repurchases its own stock with $100,000,

and you sell 100 shares to the firm, then you will

receive $1,000 in cash. You still own 900 shares of the

flrms sLock, whlch are worLh $9,000.

10

Share repurchases vs cash dividends

In the real world, there are some accounting differences between a

share repurchase and a cash dividend. The important difference is

in the tax treatment. A repurchase has a significant tax advantage

over a cash dividend.

A dividend is taxed and a shareholder has no choice about whether or

not to receive the dividend.

In a repurchase, a shareholder pays taxes only if (1) the shareholders

actually choose to sell, and (2) the shareholder has a taxable capital

gain on the sale.

Because of the favourable tax treatment of capital gains, a

repurchase is a very sensible alternative to an extra dividend.

Stock repurchase can be used to achieve other corporate goals such

as alLerlng Lhe flrms caplLal sLrucLure or as a Lakeover defence.

Many firms repurchase shares because management believes the

stock is undervalued. Firms repurchasing shares in general

experience an increase in shareholder return.

11

MM dividend-irrelevance proposition

We define dividend policy as the trade-off

between retaining earnings on the one hand and

paying out cash and issuing shares on the other.

MM proves that in an ideal world, that is there

are neither taxes nor transaction fees, the market

is efficient, investors are indifferent to dividend

policy. The value of the firm is unaffected by

dividend policy.

Since investors do not need dividends to convert

shares to cash they will not pay higher prices for firms

with higher dividend payouts.

12

MM dividend-irrelevance proposition:

an illustration

Assume that at date 0, the managers of all equity firm A know that the firm

will receive a cash flow of $10,000 immediately and another $10,000 next

year. In addition, the discount rate is 10% and the number of shares

outstanding is 1,000.

The current dividend policy: At the present time, dividends at each date

are set equal to the cash flow of $10,000. The value of the firm can be

calculated by discounting these dividends.

The dividends per share = $10, so the price is P = 10 +10/(1+10%) =

$19.09/share.

After the dividend is paid, at date 0, the stock price will immediately fall to

19.09 10 = $9.09.

Alternative Policy: Pay a dividend of $11/share at date 0, which is a total

dividend of $11,000.

Because the cash flow is only $10,000, the extra $1,000 must be raised by

issuing stock. As the required rate of return is 10%, the new shareholders will

demand $1,100 of date 1 cash flow, leaving only $8,900 to the old shares.

The value of each share is 11 + 8.9/(1+10%) = $19.09

ame! o, Lhe flrms value ls unaffecLed by dlvldend pollcy.

13

MM dividend-irrelevance proposition:

an illustration

Suppose investor X prefers the current dividend policy; that is, $10

dividends at both date 0 and date 1.

If the firm proposes to adopt the alternative policy, will she be

disappointed? No, because she can easily reinvest the $1 of

unneeded funds received at date 0, yielding an incremental return

of $1.1 at date 1. Thus, she could receive her desired net cash flow

of $11 1 = $10 at date 0 and $8.9 + 1.1 = $10 at date 1.

Conversely, if investor Y prefers $11 of dividend payment at date 0

and $8.9 of dividend payment at date 1, but the firm adopts the

current dividend policy. At date 0, he can sell off shares totalling $1,

his cash flow at date 0 would be $10 + 1 = 11. As a sale of $1 of

stock at date 0 will reduce his CFs by $1.1 date 1. So his net cash

inflow at date 1 would be $10 - $1.1 = $8.9.

The extra $1 is called homemade dividend. So if an investor prefers

more dividend today, he or she can create a homemade dividend.

14

Why dividends may increase firm value

Market imperfections: Theoretically, lnvesLors can generaLe homemade

dlvldends" from sLocks paylng no dlvldends aL all by selllng off a small fracLlon of

his or her holdings. But some investors have a natural preference for high payout

stocks, because the costs of homemade dividends may be high (transaction cost,

taxes), it is simpler and cheaper to receive a cash dividend. These clients increase

the price of the stock through their demand for a dividend paying stock.

Dividend as signals: Dividend increases represent signals of favourable expected

earnings. Firms will raise dividends only when future earnings and cash flows are

expected to be large enough to sustain the dividend in the new level. Similarly, a

dividend cut is often a signal that the firm is in trouble. Such a cut is usually not a

voluntary, planned change in dividend policy. Instead, it typically signals that

management does not think that the current dividend policy can be maintained. In

other words, dividend policy is a form of communications to the market about

future prospects. This is called the information content of dividends.

So firm value is not increased by increased dividends, but firm value increases if

dlvldend lncreases slgnal Lhe flrms fuLure prospecLs. ulvldend lncreases send good

news about CF and earnings. Dividend cuts send bad news.

15

Why Dividends May Reduce Firm Value

If dividends are taxed more heavily than capital

gains, then a policy of paying high dividends

would hurt firm value.

In Canada, both capital gains and dividends are

taxed at a lower rate than interest and other types

of income.

16

Why Dividends May Reduce Firm Value

17

Why dividends may reduce firm value:

an example

We consider a situation in which dividends are taxed at 30% and capital gains

are not taxed at all. Suppose a shareholder is considering the stock of firm

G, which pays no dividends and firm D which pays a dividend. Firm G stock

currenLly sells for $100. nexL years prlce ls expecLed Lo be $120. 1he

shareholders in firm G thus expect a $20 capital gain.

For firm G, no dividend is paid.

Pre-tax rate of return = 20/100 = 20%

After-tax rate of return = 20%, because capital gains are not taxed.

Suppose firm D is expected to pay a $20 dividend next year. The stock price is

expected to be $100 after the dividend payment.

If the stocks of firms G and D are equally risky, the market prices must be set

so that their after-tax return on firm D must thus be 20%. What will be the

price of stock in firm D, P

D

?

, then P

D

= $95.

18

D

D

P

P ) 3 . 0 1 ( 20 ) 100 (

% 20

Taxes vs capital gains: dividend

clientele effects

For dividends, individuals face a lower tax rate due to the dividend tax

credit, whereas Canadian public corporations do not pay any tax on

dividend income received from another Canadian corporation.

For capital gains, only 50% of the realized capital gains are taxable. In

addition, taxation takes place only when capital gains are realized.

Stockholders can choose when to sell their shares and thus when to pay

the capital gains tax.

For some investors, dividends may be taxed more heavily than capital

gains. Obviously, these investors prefer income from capital gains. Firms

that can convert dividends to capital gains by shifting their dividend

policies would attract these investors. For others, capital gains may be

taxed more heavily than dividends. These investors would prefer high-

dividend yield stocks. Such investors would be attracted to companies that

switch a low dividend payout to a high dividend payout policy.

This effect is called dividend clientele effect. Because different groups of

investors desire different levels of dividends, when a firm chooses a

particular dividend policy, the only effect is to attract a particular clientele.

19

CH 26: Risk Management

1 06/04/2014

Derivatives, hedging, and risk

A derivative is a financial instrument whose

payoffs and values are derived from, or

depend on, something else (the underlying).

Options

Forwards

Futures

Swaps

2 06/04/2014

Types of traders

Hedgers: hedgers use derivatives to reduce

the risk they face from potential future

movements in a market variable.

Hedging: when a firm reduces its risk exposure, it

is said to be hedging.

Speculators: they use derivatives to bet on the

future direction of a market variable.

Arbitrageurs: they take offsetting positions in

two or more instruments to lock in a profit.

06/04/2014 3

Why hedge

Most companies are in the business of manufacturing or

retailing or wholesaling or providing a service. They have no

particular skills or expertise in predicting variables such as

interest rates, exchange rate, and commodity prices. It makes

sense for them to hedge the risks associated with these

variables as they arise. The companies can then focus on their

main activities, in which they do have particular skills and

expertise. By hedging, they avoid unpleasant surprises such as

sharp rises in the prices of a commodity. It makes life simpler

for the firm and allows it to concentrate on its own business.

Secondly, it does not cost much ( if forwards are used, the cost