Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Flores - Corrido

Uploaded by

Kevin Chau0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

51 views18 pagesMusic 26

Original Title

Flores+-+Corrido

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMusic 26

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

51 views18 pagesFlores - Corrido

Uploaded by

Kevin ChauMusic 26

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 18

The Corrido and the Emergence of Texas-Mexican Social Identity

Author(s): Richard R. Flores

Source: The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 105, No. 416 (Spring, 1992), pp. 166-182

Published by: American Folklore Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/541084 .

Accessed: 17/01/2011 15:54

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=folk. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Folklore Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal

of American Folklore.

http://www.jstor.org

RICHARD R. FLORES

The Corrido and the

Emergence

of Texas-Mexican Social

Identity

The

scholarship

on the Lower-Border corrido

of

South Texas reveals how this

genre

is

itself

related to the cultural tension that has existed

along

the Texas-

Mexico border since the

early

1800s. This article shows how "Los

Sediciosos,"

a corrido that

appeared

sometime

after 1915,

shifts

the boundaries

of

the classic

narrative

form of

the corrido in

ways

that

anticipate future

Mexican-American

and

Chicano/Chicana

narrative

practices.

In

essence,

folklore performance

in

South Texas is the vehicle

through

which the

identity of

an

emerging group of

people,

the

mexicotejano,

or

Texas-Mexican,

is

expressed.

THE SCHOLARSHIP ON THE

LOWER-BORDER

"CORRIDO"

[folk ballad]

of South

Texas shows how the social world that

produced

this narrative form

posited

the notion of a unified and collective Mexican hero

fighting against

the Texas

Rangers.

As

such,

this

genre

is

deeply

related to the cultural and national con-

flict that has existed

along

the Texas-Mexico border since the

early

1800s. The

purpose

of this article is to show that soon after the events

surrounding

the

Plan de San

Diego

in

1915,

the narrative form of the corrido

gave way,

if

only

momentarily,

to the

emergent

consciousness of Texas-Mexican social iden-

tity,

a consciousness different from that

expressed by

the

poetics

of the Mex-

ican hero. That

is,

the text of the corrido "Los

Sediciosos,"

which is the focus

of this

article,

begins

to

distinguish

between two

types

of Mexicans: the

puro

mexicano

[true-born Mexican],

whose

identity

and consciousness is related

more to the

politics

of

Mexico;

and the

mexicotejano [Texas-Mexican],

whose

identity

is

shaped by

issues of ethnic

identity

in the United States. Further-

more,

although

it has been said that the cohesiveness of the corrido is that it

speaks

in a

singular

voice,

and that it

represents

the communal and

integrated

character of the

community

from which the corrido's authors and audience

descend

(Saldivar 1990),

I

wish to show that it is

precisely

in the narrativization

of the actions of the Seditionists in

1915,

in the text of "Los

Sediciosos,"

that

a new social

experience

and

identity,

however uneven and

incomplete,

shifts

the formal boundaries of the corrido

by adding

a second voice to its mono-

vocal

form.'

In

essence,

the folk

performance

of the corrido "Los Sediciosos"

Richard R. Flores is assistant

professor, Department ofAnthropology

and Chicano Studies

Program, University of

Wisconsin,

Madison

Flores,

The Corrido and the

Emergence of

Texas-Mexican Social

Identity

167

becomes the vehicle for

signaling

the

emergent

consciousness of the mexico-

tejano,

or

Texas-Mexican, and,

as

such,

is a

precursor

of future

"Mexican-

American,"

"Chicano" and "Chicana" narrative formations.2

The

Anglo-Mexican

World: 1800-1915

The

history

of Texas-Mexico border clashes between 1850 and 1910 is dom-

inated

by

crisis, tension,

and conflict between

Anglos

and

Mexicans.3

How-

ever,

of all the

issues,

those

involving

national

boundaries,

property,

and the

use of land in

general

were the most

significant. Beginning

in the

early

1800s,

the movement of

Anglo-American

settlers into Mexican

territory

caused the

first

major

confrontation between these two

groups.

Border

disputes

contin-

ued

throughout

the first three decades of the

century

and culminated in the

war for Texas

independence

that ended in 1836 and the U.S. declaration of

war

against

Mexico in 1846.

Expansion

of U.S.

territory

and the

development

of American economic interest served as

major

causes of this war.

The defeat of the Mexicans ended with the

signing

of the

"Treaty

of Gua-

dalupe-Hidalgo"

on 2

February

1848. The

key

elements of the

treaty

were the

establishment of the Rio Grande River as the border between the two countries

and the

ceding

of the lands to the United States. This

territory

included the

current states of

California,

New

Mexico, Texas, Nevada,

and

parts

of Col-

orado, Arizona,

and Utah. The Mexican

people living

in these areas had a

choice of

remaining

and

becoming

citizens of the United States or

returning

to Mexico. For those who

stayed,

land

grants

and

property

were to be re-

spected

as well as the Mexican culture and

language.

The

signing

of the

treaty

put

a formal end to the

hostilities, but,

in

effect,

it was the

beginning

of a new

era of conflicts and

struggles

between Mexicans in the U.S. and their

Anglo

neighbors.

The

rights guaranteed by

the

Treaty

of

Guadalupe-Hidalgo

to the Mexican

people-ownership

of the

land,

due

process

of

law,

maintenance of the cul-

ture,

and others-were

quickly

undermined

by

the

Anglo community (Acufia

1981).

As could be

expected,

control and

ownership

of land was a

key

factor

in

establishing Anglo-Texan authority

in the

territory. "Immediately

after the

war with

Mexico,"

Richmond

claims,

a

greedy

land

grab

ensued which alienated the Mexican

community

in Texas for

good.

....

The

authorities declared "vacant" all communal and

municipal

lands distributed earlier. The General

Law of 1852 validated some

original Spanish

land

grants

but

many

claims were lost

simply

for

the lack of

representation

before the commission as

required by

law. The "vacant" lands were

then sold to

Anglos

at

very

low

prices. [Richmond 1980:3]

These and similar

practices

of the

growing Anglo community

did not find

passive

victims in the Mexican

people.

In

July 1859Juan Cortina, a U.S. citi-

zen under the

Treaty

of

Guadalupe-Hidalgo,

shot Marshall Bob

Spears

of

Brownsville after

seeing

him

pistol whip

a Mexican. After

shooting Spears,

168

Journal of

American Folklore 105

(1992)

Cortina enlisted the

support

of several landowners in the area and wrote a

manifesto

against

the

Anglo-Texans.

In an effort to strike back at those who

had

persecuted

Mexicans as well as stolen their

land,

Cortina attacked

Brownsville,

defeated the local Brownsville and Matamoros militias

(as

well

as the Texas

Rangers),

and raised the Mexican

flag

over the

city.

In

February

of

1860,

Robert E. Lee was sent after Cortina. Cortina

eventually

fled

to the

Mexican side of the

border,

turning

his interest to Mexico's war with the

French.

Although

the

conflict

ceased with Cortina on the Mexican side of the

border,

the backlash from his raids would be felt for some time.

Perhaps

the best known incident of the border

conflict

years

occurred in

1901 when

Gregorio

Cortez shot and killed Sheriff W. T. Morris in self de-

fense after the two had an

argument

and

linguistic

miscommunication over the

trading

of a mare. Morris's death resulted in a massive search for Cortez

by

the Texas

Rangers.

As

they

followed him to the Mexican

border,

the

Rangers

thought

little of

shooting

innocent Mexicans whom

they

considered to be

part

of a nonexistent Cortez

gang.

In a show of

solidarity,

the Mexican

community

organized

to raise

money

and social awareness about the Cortez affair

(Paredes

1958).

One of the least known instances of border conflict occurred in 1915 and

concerns a

revolutionary plan

known as the Plan de San

Diego. Although

the

circumstances

surrounding

the

writing

of the Plan are debated

by

historians,

the Plan is believed to have been

partially

written

by

six or seven

Mexicans,

who have come to be known as the

Seditionists,

while

they

were

imprisoned

in

Monterrey,

Mexico,

in

January

1915. It was finalized

by

Basilio Ramos and

other

signatories

later that

year (Cumberland

1954;

Gomez-Quifiones

1970;

Harris and Sadler

1978;

Richmond

1980).

The Texas authorities

acquired

the

Plan when a

copy

was found in the

possession

of one of its

authors,

Basilio

Ramos,

when he was arrested in

McAllen, Texas,

in

lateJanuary

1915. Ramos

was

charged

with treason for

possession

of a

revolutionary

document,

but

when the

revolt,

as outlined in the

Plan,

failed to

materialize,

the

charges

were

dismissed and Ramos was released on 13

May

1915

(Longoria 1982:214).

The details of the Plan call for a

general uprising

of all Texas-Mexicans liv-

ing

on the border at 2:00

P.M.

on 20

February

1915. The

objective

of the

up-

rising

was to retake the territories lost to the United States in the wars of 1836

and 1846-48. This

territory, consisting

of the states of

Texas,

New

Mexico,

Arizona, Colorado,

and

California,

was to become a new

independent

Mexi-

can

republic

from which land would be

granted

to

Blacks, Indians,

and Asians

so that

they

could form their own autonomous states

(Gomez-Quifiones

1970;

Hager 1963).

With the incarceration of Ramos, 20

February passed uneventfully.

How-

ever, in late

May

and

continuing

until late fall of that

year,

border raids led

by

Aniceto

Pizafia

and Luis de la Rosa, two local Texas-Mexican Seditionists,

were carried out, almost

weekly, against

the

Anglo-Texan community.

These

raids consisted of attacks on individuals, stores, post offices, bridges,

and rail-

Flores,

The Corrido and the

Emergence of

Texas-Mexican Social

Identity

169

roads.

Also,

as noted from the text of "Los

Sediciosos,"

the Seditionists di-

rected

special aggression against

the Texas

Rangers.

Pizafia and de la Rosa car-

ried out their attacks with no more than a hundred men-the numbers were

often fewer-and

they

raided as far north as the

King

Ranch in

Kleberg

County.

The United States

government responded by increasing

its

military

force on the border with

troops

from the U.S.

Army

and the Texas

Rangers

(Cumberland 1954;

Hager 1963).

On 21 October 1915 the last raid

by

the Se-

ditionists took

place

at

Ojo

de

Agua, putting

an end to the

revolutionary

effort

connected with the Plan de San

Diego.4

The Lower-Border Corrido Tradition:

The Social Content

of

Aesthetic Form

The work of Americo Paredes has set the standard for corrido

scholarship,

and his

book,

With His Pistol in His Hand: A Border Ballad and its Hero

(1958),

is a classic text on the

subject. According

to

Paredes,

the corrido of border

conflict

originated

in 1859 with the Cortina incident and reached its

height

in

1915 with the border raids conducted

by

the Seditionists. This

genre

is rec-

ognized through

its

highly

formalized narrative

style, exemplified by

its oc-

tosyllabic

lines and

regulated

use of

rhyme

and

assonance,

and built

upon

the

use of its

key metaphors

of "rinche"

(the

name

given

to the Texas

Rangers

that

makes use of the

negative Spanish language

suffix

-inche)

and the Mexican hero

"con

su

pistola

en la mano"

[with

his

pistol

in his

hand]. Relatedly,

the corrido

speaks

of the Mexican hero

standing up

to U.S.

authorities,

usually repre-

sented

by

the

rinches,

and

boasting

about his

bravery.

In most

cases,

descrip-

tions of horses can be

found,

as well as the "clown"

who,

on the

verge

of

tears,

exists in

sharp

contrast to the honor of the Mexican hero

(Paredes 1974).

Therefore,

the corrido

strategically adapts

various

aspects

of

conflict

so that

they

become battles between the "rinches" and the Mexican "heroes." And to

the extent that

conflict

between

Anglos

and Mexicans on the Texas-Mexico

border is due to cultural and national

difference,

the border corrido functions

as an

expression

of resistance.

Although

the

majority

of corridos of border conflict are based on historical

fact and

depict

the actions and events of actual

characters,

the corrido is also a

vehicle for

interpreting

historical events. Paredes states that a ballad tradition

"crystallize[s]

at one

particular

time and

place

into a whole ballad

corpus,

which

by its

very weight impresses itself on the consciousness of the people"

(1963:231-235).

This

crystallization

is critical in

understanding

the narrative

(and

semic)

cohesiveness of the

corrido, because the corrido form is not

just

a

vehicle for

representing day-to-day

events

(like

the classic corridos of

Juan

Cortina, Gregorio Cortez, and

others),

but one that

expresses

the collective

ideas and social discourse of Mexicans in South Texas. In a case

study

on this

point,

Paredes

analyzes

the account

ofJos6 Mosqueda,

an outlaw who robbed

a train

carrying approximately $75,000 in

gold

and silver from

Brownsville,

170

Journal ofAmerican

Folklore 105

(1992)

Texas,

to Point Isabel. The "Corrido

ofJos6 Mosqueda,"

however,

denies the

events of the

robbery,

and instead fabricates a new

sequence

of events in which

Mosqueda

becomes a hero of border conflict. In this

example,

actual events

are

changed

to fit the

culturally

mediated narrative form of the border-conflict

corrido. Paredes

anticipates,

in a

perhaps

unconscious

way,

the later work of

critical theorist Fredric

Jameson by showing

how narratives are

reshaped

in

ways

that

signal

their social and class formations

(Jameson 1981).

At this

point,

the social content of the corrido of border conflict becomes

the focus of

my inquiry.

For,

if

history

has been excised for the

purpose

of

constructing

a cohesive

(and ideological)

narrative,

those that fit the classic

characteristics of the corrido

form,

the task of

recovering

this lost

history

calls

for a

rereading

and

rewriting through

the narrative discourse

itself.

Of Heroes and Rinches

The classic form of the corrido is not confined to

Cortina, Cortez,

or the

Seditionists,

but is found in most corridos of border conflict. In his

book,

A

Texas-Mexican

Cancionero,

Paredes mentions 33

songs

in the

chapter "Songs

of Border Conflict"

(1976).

Of these

songs,

18 concern the mexicano commu-

nity,

and 12

specifically

mention the Mexican hero armed with a

pistol

or rifle.

In these

texts,

the hero is the idealized and

symbolic

Mexican "who defends

his

right

with his

pistol

in his

hand,

and who either

escapes

at the end or

goes

down before

superior

odds in a sense victor even in defeat"

(Paredes 1958:124).

But at the level of

form,

the Mexican hero is not the individual historical

figure

(as

was evidenced in the "Corrido of

Jose Mosqueda"),

but embodies the

larger,

collective

figuration

of the local

community.

The extent to which the

Mexican hero is

synonymous

with the fate of the local

community

has led

Ram6n Saldivar to conclude that a distinction between the Mexican hero and

the

community

as a whole cannot be

maintained,

and that the Mexican hero

stands "not as an individual" but as a

poetically

constructed

figure represent-

ing

the

community

that constitutes him

(1990:36). Considering

this,

the Mex-

ican heroes of the

corrido,

like the narrative

figures

of

Cortez, Cortina,

and

others,

are no

longer

individual

personas,

but discursive

figures

who are de-

rived from the social and cultural world of the corrido's authors and audience.

The narrative and collective constructions of the corridos are not limited to

the Mexican

hero,

but also

provide

for their narrative

antagonist

in the

"rinche."

Through

this

poetic

form, the mexicano

community objectified

its

mistrust of the

Anglo-Texans

who assumed social, cultural, and economic

dominance in the area

through

the brutal activities of the Texas

Rangers.

As

Paredes states,

The Texas

Ranger always

carries a

rusty

old

gun

in his

saddlebags.

This is for when he kills an

unarmed Mexican. He

drops

the

gun

beside the

body

and then claims he killed the Mexican in

self-defense and after a furious battle.

[Paredes 1958:24]

Flores,

The Corrido and the

Emergence of

Texas-Mexican Social

Identity

171

The term "rinche" not

only signifies

mistrust or

deceit,

but also the violence

and

exploitation

inflicted

upon

the mexicano

community by

the Texas

Rang-

ers. It was not uncommon for

Rangers, acting

as

judge, jury,

and execution-

ers,

to

summarily lynch

Mexicans

suspected

of

thievery

or

banditry.

Nor was

it unknown for the

Rangers

to seize the land of Mexicans so that it could be

sold

cheaply

to

incoming Anglo-Texan entrepreneurs (Montejano 1987).

In

sum,

the Lower-Border corrido stemmed from the

political

and cultural

po-

etics of the mexicano

community

and was a means of

responding

to and re-

sisting

the encroachment and

exploitation

of the

Anglo-Texan.

Of

Rangers

and Bandits

The

binary opposition

of Mexican "heroes" and

Anglo

"rinches" found in

border corridos is not

only

a textual construction but also

dialogically

related

to the

accepted Anglo-Texan

view of the

relationship

between Mexicans and

the Texas

Rangers.

This is

perhaps

best summarized

by Lyndon Johnson

in

his foreword to the second edition of Walter Prescott Webb's The Texas

Rang-

ers

(1965:x),

where he characterizes the Texas

Rangers

as men

engaged

in a

"never-ending quest

for an

orderly,

secure,

but

open

and free

society.

. .

."

And,

whereas Webb

perpetuates,

even

celebrates,

the Texas

Rangers

as

knights pursuing

a chivalrous

quest

for

order,

he cannot

entirely

overlook the

suffering

and

"orgy

of bloodshed"

they

inflicted on the Mexican

population

of Texas

(Webb 1965:478).

As

such,

the Texas

Rangers signified

the kind of

power

and blind ambition that was

necessary

for

gaining

land and commercial

dominance in this once Mexican

territory.

Anglo-Texans

also created their own

generally agreed upon

notion of the

Mexican

character,

as seen in the

way

the

exploits

of the Seditionists were dis-

cussed in the local

Anglo-Texas press. Although

the

Plan,

from the

perspec-

tive of the Mexicans who wrote

it,

was based

upon

the reclamation of lost or

stolen

land,

the

Anglo-Texan

discourse

concerning

the raids of the Seditionists

was

quite

different. The headline of a San Antonio

paper

of 9

August

1915

reads: "Border Outlaws

Engage Rangers

on

Norias

Ranch"

(San

Antonio Ex-

press:1);

the Brownsville

paper

of 27

August

1915 claims:

"Alleged Norias

Bandit Killed-An Encounter North of

Edinburg

between

Rangers

and

sup-

posed

Bandits"

(Brownsville Herald:1);

and in Del

Rio, Texas,

the events take

on heightened proportions as reported in a San Antonio paper on 27 August

1915: "Del Rio Ask for more Protection-A

Heavy

Increase in Mexican

Pop-

ulation alarms citizens of Val Verde

County" (San

Antonio

Express:2).

In these

accounts, the

political

and social

exploits

of a few Mexican revolutionaries are

presented

as the activities of

"bandits," generalized

to the entire

population,

and are

responsible

for

promoting

an

image

of Mexicans as

"lazy, dirty,

thiev-

ing, devious, conspiratorial, sexually hyperactive

and

overly

fond of alcohol"

(Lim6n 1983:217).

172

Journal of

American Folklore 105

(1992)

The Lower-Border corrido

dialogically responds

to the

Anglo

discourse

represented by

the Texas

Rangers through

its own construction of

Anglos

as

rinches

and,

more

important,

the Mexican as a "hero with his

pistol

in his

hand."

Corrido Form and

Emergent Identity

In his

analysis

of the narrative form of the

corrido,

John

McDowell

(1981)

articulates several

key

features that are

significant

for

my analysis

of "Los Sed-

iciosos." Lower-Border

corridos,

according

to

McDowell,

consist of narra-

tive

elements,

interspersed by dialogue

or

reported speech,

that function as

icons of the

experiential

substratum and lead to a sense of identification for the

corrido

community.

This is achieved

through

the use of an

impersonal

and

distancing

authorial voice that

separates

the narrator from the events

depicted,

allowing

the narrative material to "move from

iconicity

to identification"

(1981:49). Essentially,

the authorial voice of the

corrido,

through impersonal

narrative and

reported speech, expresses

the values and sentiments located in

the mexicano

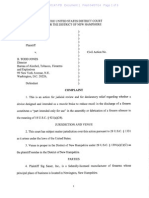

community (see Fig. 1).5

As

diagramed,

the authorial voice in the

corrido,

although

it

gives

rise to

dialogic

elements

through reported speech,

frames the narrative as a

cohesive,

unified,

and monolithic

representation

of the collective corrido

community.

Against

this

backdrop,

the

significance

of a text that alters this

form,

such as

"Los

Sediciosos,"

is

significant.

The

striking

difference between the text of "Los Sediciosos" and the earlier

corridos of

Cortina, Cortez,

and other heroic

figures

is the

presence

of two

authorial voices. This is detected in the tension between the

"puro

mexicano"

and the

"mexicotejano.

"6 The social world of earlier corridos

posited

a collec-

tive and unified

(homogeneous)

Mexican

hero(es) against

the

Anglo

rinches.

In "Los

Sediciosos,"

this has

changed;

the notion of a

homogeneous

border

AUTHORIAL VOICE L NARRATIVE

REPORTED SPEECH

l DIALOGUE

Mexican Hero

Rinche/Americano

AUTHORIAL VOICE '

NARRATIVE

Figure

1.

Diagram

of the classic corrido form.

Flores,

The Corrido and the

Emergence of

Texas-Mexican Social

Identity 173

Mexican has

given way

to two voices: the

pure

Mexican and the Texas-Mex-

ican,

or

mexicotejano,

as the text of "Los Sediciosos" states.

Ya la mecha estai encendida Now the fuse is lit

por

los

puros mexicanos, by

the true-born

Mexicans,

y

los

que

van a

pagarla

and it will be the Texas-Mexicans

son los

mexicotejanos.

who will have to

pay

the

price.

Although

the

phrase "mexicotejano" appears only

once in this literal for-

mat,

the distinction is carried out in the next two stanzas.

Ya la mecha estai encendida Now the fuse is

lit,

con azul

y

colorado,

in blue and

red,

y

los

que

van a

pagarla

and it will be those on this

side,

van a ser los de este lado. who will have to

pay

the

price.

Ya la mecha estai

encendida,

Now the fuse is

lit,

muy

bonita

y

colorada,

very

nice and

red,

y

la vamos a

pagar

and it will be those of us who are

blameless,

los

que

no debemos nada. who will have to

pay

the

price.

Breaking

from its traditional

form,

the corrido of "Los

Sediciosos" exhibits

the

following

characteristics

(see Fig. 2).

Stanzas 1-3

(see Appendix)

constitute

authorial voice 1

(AVI),

but the narrative

changes

in stanzas 4-6 create another

voice,

that of authorial voice 2

(AV2). Whereas

Avl

is,

as McDowell

suggests,

impersonal

in

tone,

that is not the case with

AV2,

which

begins

to bemoan the

wrath the

mexicotejano community

will encounter as a result of the

exploits

of the Seditionists

("los que

van a

pagarla

van a ser los de este

lado").

This shift in

tone

signifies

a crucial

change

in the classical form of the Lower-Border cor-

rido. Because if it is true that "deeds do not have

clearly

distinct

public

and

private reasons, motivations,

or

consequences,

but

only collectively symbolic

dimensions,"

as Saldivar

says (1990:37),

the concern over the

consequences

of

heroic deeds

signals

a variation in the classic corrido form. I will

explore

the

meaning

of this

change

below.

The

dialogic

element of the text follows the corrido form outlined

by

McDowell with

only slight

variation. Instead of more direct and numerous

AUTORIAL VOICETHAL

VoICE'--- 4 AUTHORIAL

VOICE-

NARRATIVE

I

REPORTED SPEECH

DIALOGUE

Los Sediciosos Los Sediciosos Americano

I

AUTHORIAL

VOICE'&2 NARRATIVE

Figure

2.

Diagram

of the form of the corrido "Los

Sediciosos."

174

Journal ofAmerican

Folklore 105

(1992)

exchanges

between the Mexican

hero(es)

and the rinches or

americanos,

most

of the

dialogue

takes

place

between the Seditionists themselves. The one

place

where the americano does

speak,

in stanza

11,

he does so

parodically,

"con su

sombrero en las manos"

[with

his hat in his

hand].

Like the

introductory

narrative,

the

concluding

narrative also

diverges

from

the classic corrido form. Instead of the

impersonal retelling

of

information,

as

in stanzas

13, 14,

and

20,

a

personal

narrative voice

again expresses

concern

over the

consequences

of the deeds of the

Seditionists,

as seen in the

phrase

"nos

dejaron

una veta colorada"

[they

have left us a red swath to remember them

by].

This leads to a fusion of authorial voices

(AV1-Av2),

as found in stanzas

21-23.

At this

point

I would like to introduce Bakhtin's discussion of "authorita-

tive" and

"internally persuasive"

discourse as a means of

untangling

these di-

vergent

voices in "Los

Sediciosos."

Authoritative

discourse,

for

Bakhtin,

is a

narrative that is

preeminent, powerful,

and

cohesive,

forming

the

singular

voice of

political

and moral

authority

that

shapes

and

incorporates

other dis-

cursive forms to itself

(here

the

significance

of the outlaw-made-hero

rings

with

special acuity) (1981:343). Subsequently,

for

Bakhtin,

as well as for the

classic

corrido,

this discourse cannot be

"divided,"

or for the

purposes

of this

text,

hyphenated (1981:343).

From

my reading,

authoritative discourse is the

impersonal

voice found in the Lower-Border

corrido,

one that

coheres,

uni-

fies,

and binds "without internal contradiction"

(1981:342).

Whereas Bakhtin

sees it as the "word of fathers"

(1981:344),

I

take it as the "word of

heroes";

and whereas he sees it as the "voice of tradition" and

"acknowledged

truths"

(1981:344),

I

read it as the demand of form.

But,

as noted

above,

"Los Sediciosos"

encompasses

more than one authorial

voice. This second

voice,

I

suggest,

that of the

mexicotejano (Av2), is,

follow-

ing

Bakhtin,

an

"internally persuasive"

discourse that is not backed

by

au-

thority,

tradition,

or

form,

but one "born in a zone of contact"

(1981:346).

This voice

signals

a new set of

emergent meanings

that stem from the

geo-

graphical

and cultural border zone where the U.S. and Mexico

meet;

it is a

voice that can no

longer

be contained

by

the

unifying

discourse of the Mexican

hero,

but

gives

rise to a

new,

yet incomplete,

voice in the

mexicotejano.

The

uniqueness

of this discourse for "Los Sediciosos" cannot be understated. No-

where in Paredes's collection of

songs

from the Lower Border does the

phrase

"mexicotejano"

exist until this

text;

and such "narrativization" works

against

the

weight

of a "whole ballad

corpus"

that has

posited

the notion of a unified

Mexican hero. I

suggest,

therefore, that the addition of this narrative voice

signals

a different kind of awareness and

identity

for South Texas Mexicans. I

would add to Bakhtin that not

only

is an "individual's

becoming"

marked

by

a

"gap"

between authoritative and

internally persuasive

discourse, but so is

that of a

"group" (1981:342).

The

"becoming"

witnessed in this text is that of

an

emergent identity trying

to

speak

in an

expressive,

formal voice, over and

above the voice of the authoritative "Mexican" hero. And

although

this voice

Flores,

The Corrido and the

Emergence of

Texas-Mexican Social

Identity

175

does not

yet represent

that of an autonomous

"group,"

we have the

begin-

nings

of a

differentiated,

neither Mexican nor

American,

community.

Accordingly,

references to los de este lado

[those

on this

side]

and los

que

no

debemos nada

[those

of us who are

blameless], synonyms

for the

mexicotejano,

stem from the

dialogic

interaction between this

emergent, internally persua-

sive discourse of ethnic consciousness and the authoritative and formal voice

expressed

in the Mexican hero. One

major

event to substantiate this occurred

in

1911, just prior

to the

peak

of the corrido

period.

This is the

primer

con-

greso

mexicanista de 1911

[First

Mexican

Congress

of

1911],

which took

place

in

Laredo,

Texas. This

congreso, organized by

Nacasio Idar and his

family,

met to discuss five issues:

(1) deteriorating

Texas-Mexican economic condi-

tions;

(2)

the

already perceptible

loss of Mexican culture and the

Spanish

lan-

guage among

border

inhabitants;

(3) general

social

discrimination;

(4)

educa-

tion

discrimination;

and

(5)

the

officially

tolerated

lynchings

of Texas-Mexi-

cans

(Lim6n 1974:87-88).

The

primer congreso

mexicanista is

important

in

that it

represents

the mexicano

community's emerging recognition

of its

rights

and

place

in American

society.

These were not international or cross-border

grievances,

but the

grievances

of a

community

that,

although experiencing

social

discrimination,

was

just beginning

to see itself as

part

of U.S.

society.

Although

Lim6n's

article on the

primer congreso

mexicanista refers to

many

of the

people

with the referent

"Texas-Mexican,"

the

majority

of those

he

quotes

refer to themselves as "mexicanos."

Only

one

person

uses the

phrase

"Texas-Mexican"

representing

the

new,

and

many

times

uneven,

qualities

of

emergent identity (Williams 1977).

However,

it

goes

without

saying

that the

entire

agenda

of the

congreso signaled

a

growing

distinction between those

who saw themselves as Mexican in the national and

geographic

sense,

like the

Seditionists,

and the new

mexicotejanos.

The text of "Los Sediciosos" contains other evidence of this new and

emerg-

ing

social

identity.

In the same stanzas

quoted

above there is reference to the

colors blue and red: "Ya la mecha esta encendida con azul

y

colorado. Ya la mecha

esta encendida

muy

bonita

y

colorada." Reference to blue and red has a

very spe-

cific

political meaning

at this historical moment

(Gonzalez 1930:89).

The

"pu-

ros

mexicanos"

light

their fires in blue and

red,

colors associated with the dem-

ocratic

and

republican parties

in South

Texas,

because these

parties

do not

rep-

resent their interests. The

political process,

American

by design

and

jurisdic-

tion,

is of no

significance

to the

puros

mexicanos since

they

are

culturally

and

ideologically Mexican.

A

recruiting

handbill for the Plan de San

Diego

refers

to them as "los buenos

mexicanos, lospatriotas" [the good Mexicans, the

patriots]

(Montejano 1987:154).

The

puro

mexicano is a

patriot,

not of the United

States, but of Mexico. It is

precisely here, in the difference between the

puros

mexicanos and

mexicotejanos,

that the

unity

of the corrido form shifts

by

in-

corporating

a second authorial voice

(AV2).

Although

at one

point Paredes,

writing

about

Gregorio Cortez, could claim that "the

point

of view is local

rather than national"

(1958:183),

I would

suggest that, 15

years later, the view-

176

Journal of

American Folklore 105

(1992)

point

is neither local nor national but "remains on that

precarious utopian

mar-

gin

between the two"

(Saldivar 1990:174).

The text of "Los Sediciosos"

speaks

in two distinct voices. Those who

speak

as

puros

mexicanos see

Mexico,

like their Mexican

identity,

as a haven to

which

they

return

(it

is no coincidence that the heroic

figures

of

Cortina,

Cor-

tez,

and the Seditionists cross the border into

Mexico).

As

such,

the Lower-

Border corrido is the collective

expression

of national and

geo-cultural

con-

flict. But the text of "Los Sediciosos" is

quite

different. The

communal,

col-

lective voice is

split,

no

longer

Mexican,

but

mexicotejano, reflexively signal-

ing

the

mexicotejano community

as the source and

place

of its construction.

When the Lower-Border corrido has the Mexican "hero" and the

Anglo

"rinche" as its

primary

characters,

issues of national and cultural conflict are

represented,

never

moving beyond

the "Mexicanness" of the mexicano hero

or the "Americanness" of the

Anglo

rinche.

However,

as in the case of the

mexicotejanos,

"los de este

lado,"

once

identity

is constructed from the social

borders of socioeconomic and historical conditions of

marginalization

be-

tween two cultures, the

expressive,

discursive form of that

identity

also

changes.7

The

personal

narrative voice of "Los Sediciosos" is not that of the

hero "with his

pistol

in his

hand, " but of "los de este lado"

[those

on this

side],

who must face the

consequences

of an

increasingly marginalized identity.

Therefore,

the authorial tension between the

puro

mexicano and mexicote-

jano,

between those who flee to Mexico and those who

stay

and

"pay

the

price," signals

an

emergent

social

identity evolving

from that

"unstable

bor-

derline of

difference,"

as Saldivar refers to it

(1990:174),

that

distinguishes

the

mexicotejano

from both Mexicans and Americans. As

such,

the narrative

voice of the

mexicotejano,

and the

emergent identity

it

represents,

shift the

formal boundaries of the Lower-Border corrido.

Essentially,

once border conflict ceases to be the

primary

issue,

and the nar-

rative terrain is the

marginalized space

between U.S. and Mexican

culture,

and

not the

U.S.-Mexico border,

new narrative forms

emerge, changing

the role

of the corrido and its

"interpretations

of the historical world"

(Saldivar

1990:48).'

However,

future narratives do not

appear

sui

generis,

but

emerge

from,

and draw

upon,

earlier

expressive

forms. Here lies the

significance

of

"Los Sediciosos": it

symbolically

and

formally begins

to

anticipate

a con-

sciousness found in future Chicano/Chicana narrative forms. As

such,

"Los

Sediciosos" sets the narrative

stage

and enacts

particular expressive precondi-

tions of

political

consciousness that, a few

years later, are

realized.9

As Mario

Garcia claims,

The Mexican-American Generation, as a

political entity, began

to come of

age

in the 1930s, but

its

embryo

can be detected in the

Roaring

Twenties. In this decade Mexican Americans

already

stressed the need for a new

political

direction for themselves based on two basic needs: the im-

portance

of

instilling

a new consiousness

among

Mexican Americans-to

develop

a "new Mex-

ican" in the United States-and the need to

organize

new forms of

political

and civic

organiza-

Flores,

The Corrido and the

Emergence of

Texas-Mexican Social

Identity

177

tions-a "new

politics"-that

would best serve their interests

separate

from those of Mexican

immigrants. [1989:26]

Likewise,

in an article on the

League

of United Latin American Citizens

(LULAC),

an

early

Mexican-American

political organization

that

appeared

in

the late

1920s,

O. Douglas

Weeks refers to this

group

as a "Texas-Mexican"

organization (1929).

The reference to "Texas-Mexican" is

quite

salient,

be-

cause it

represents

the extent to which this

emergent identity

had

developed

by

1929.

And,

more

important,

it reveals how narrative formations

signal

changes

in social

practice,

since

LULAC,

according

to

Garcia,

is one of the

early political organizations attempting

to

rectify

the

marginal

conditions of

mexicanos in the U. S.

(Garcia 1989).

I

contend that the

presence

of the

mexicotejano

voice in the text of "Los

Sediciosos"

anticipates, through

formal

change

and reflexive

self-reference,

the ethnic consciousness of later

generations.

At the same

time,

I do not

sug-

gest

that this

text,

and its formal

changes, signal

the

presence

of a

fully

devel-

oped

Mexican-American

identity,

or that one text constitutes an entire tradi-

tion. Nor do I

suggest

that future Mexican-American or Chicano/Chicana

narrative forms are based

directly

or

entirely

on the corrido.

Yet,

Saldivar's

claim that the corrido's collective character leaves no

space

for the

idiosyn-

cratic voice must be reconsidered. In "Los

Sediciosos,"

the

mexicotejano

ex-

presses

a collective

consciousness,

however

fleeting

and

unformed,

of the cor-

rido

community's emerging

ethnic

identity,

an

identity incapable

of

being

ex-

pressed by

the authoritative discourse of the Mexican hero. That "Los Sedi-

ciosos"

begins

to subvert the notion of a unified Mexican hero

by displacing

and

decentering

such an

identity

in favor of a

split

and

multiple

one character-

istic of Chicano/Chicana narratives of future

generations points

to the discur-

sive consonance this text

anticipates."' Although

in

many ways

the corrido

"Los

Sediciosos"

maintains elements of the classic

form-boasts,

description

of

horses,

the fearful clown

(de

la

Rosa),

and

farewell-primary

elements,

such as the sense of a unified Mexican hero and the use of authoritative dis-

course,

are no

longer present.

Instead,

the text

distinguishes

between two

types

of Mexicans: the

"puro

mexicano,"

whose

identity

stems from his Mex-

ican

allegiance,

and the

"mexicotejano,"

a cultural form born from the ethnic

margins

of Mexican and American

society.

Notes

This article is an

expanded

and revised version of a

paper

read at the American

Ethnological Society

Meet-

ing

and the Mexican Americans in Texas

History Conference, both held in the

spring

of 1991. I wish to thank

Jos6

Lim6n,

Richard

Bauman,

Olga Naijera

Ramirez, Steve

Lee,

Ram6n

Saldivar,

Lourdes

Giordani, and,

as

always,

Christine Flores for

reading

and

commenting

on earlier drafts of this article. This research has been

made

possible by support

from the Graduate School of the

University

of

Wisconsin,

Madison. I would like

to dedicate this article to Am6rico

Paredes,

whose

scholarship

and humanism have served as a model to em-

ulate,

and

Jos6

Lim6n, whose critical

insights

and

friendship

have

challenged

me to think

beyond my

own

personal

borders.

178

Journal of

American Folklore 105

(1992)

'For the sake of

clarity,

references to the Seditionists

(in English)

refer to the

people

who formulated and

executed the Plan de San

Diego,

a small but

significant revolutionary

movement on the Texas-Mexico border

in 1915

spoken

about later in this article. References to "Los Sediciosos"

(in Spanish)

refer to the corrido

describing

the events.

2My

distinction between Mexican-American and Chicano is

quite specific.

Mexican-Americans are

gen-

erally

members of the Mexican

origin population

who were born in the U.S. and differentiate themselves

from recent

immigrants

from Mexico on the basis of distinctions such as

higher

class

ranking

and social status.

Such an effort has been characterized

by

Mario Garcia as the

development

of a "new Mexican"

alongside

a

"new politics" (1989:26). I

follow

Jos6

Lim6n's

usage

of the term Chicano and use it "to

identify

an

ethnic,

nationalist individual or

position,

one

opposed

to accommodation and assimilation with United States culture

and

society" (1981:200).

For an overview of Chicano and Chicana narrative see

Saldivar (1990).

3This history

has been the

subject

of

recent,

and not so

recent, historiography.

Historical

surveys

on this

issue can be found in Acufia

(1981),

De Leon

(1983), Montejano (1987),

and Weber

(1973).

Works that are

more focused

along geographical

or

disciplinary

lines include Barrera

(1979), Foley

et al.

(1988),

Garcia

(1981),

and

Hinojosa (1983).

Several of these historical events have been

interpreted

with their own corridos. The

corridos

ofJuan Cortina, Jacinto Trevifio,

and

Gregorio

Cortez and the events

surrounding

them are

espe-

cially interesting.

For a brief

summary

of these and other historical and narrative

figures,

see Paredes

(1976,

1979).

4For

a detailed

study

of the Mexican

history

of this

period

see Alba

(1967)

and Cockcroft

(1968).

5The diagram

I have outlined is

my

own variation of McDowell's schema

(1981:48).

6In

an earlier version of this article I alluded to this second voice less

directly.

I want to thank Richard

Bauman for

encouraging

me to

develop

this idea further.

7Historical accounts of this

marginalization

can be found in Barrera

(1979), Foley

et al.

(1988),

and Mon-

tejano (1987).

8Manuel

PNna (1985)

has

suggested

that the

conjunto

music of South Texas

replaces

the corrido in

popu-

larity

after 1930 because its

expressiveness

allows it to more

effectively interpret

the class

experience

of South

Texas Mexicans. On the

changing

function of the corrido see Pefia

(1982).

9A classic

example

of how aesthetic forms

begin

to

anticipate

and set the

preconditions

of future

political

enactments and consciousness is

Raymond

Williams's discussion of how

Jacobean

dramatic form

anticipated

the

subsequent

enactment of Hobbesian

political philosophy (1981:159).

.0Lim6n

(1992)

considers the corrido as a "master

poem,"

in Harold Bloom's terms, against

which future

generations

of Chicano

poets attempt

to write their own

"strong" poems.

References

Cited

Acufia,

Rodolfo. 1981

[1972]. Occupied

America: A

History of

Chicanos. New York:

Harper &

Row.

Alba,

Victor. 1967. The Mexicans. New York:

Praeger.

Bakhtin,

M. M. 1981. The

Dialogic

Imagination.

Austin:

University

of Texas Press.

Barrera,

Mario. 1979. Race and Class in the Southwest. Notre

Dame, Ind.: University

of Notre

Dame Press.

Cockcroft,

James

D. 1968. Intellectual Precursors

of

the Mexican Revolution, 1900-1913. Austin:

University

of Texas Press.

Cumberland,

Charles C. 1954. Border Raids in the Lower Rio Grande

Valley-1915.

South-

western Historical

Quarterly

57:285-311.

De

Leon,

Arnoldo. 1983.

They

Called Them Greasers. Austin:

University

of Texas Press.

Foley, Douglas

E.,

Clarice Mota,

Donald E.

Post,

and

Ignacio

Lozano. 1988

[1977].

From Peones

to Politicos. Austin:

University

of Texas Press.

Garcia,

Mario T. 1981. Desert

Immigrants:

The Mexicans

of

El

Paso,

1880-1920. New Haven,

Conn.: Yale

University

Press.

. 1989. Mexican Americans:

Leadership, Ideology,

and

Identity

1930-1960. New Haven,

Conn.: Yale

University

Press.

Flores,

The Corrido and the

Emergence of

Texas-Mexican Social

Identity

179

Gomez-Quifiones, Juan.

1970. The Plan of San

Diego

Revisited. Aztldn 1:124-132.

Gonzalez,

Jovita.

1930. Social

Life

in

Cameron,

Starr and

Zapata

Counties. M.A. thesis.

Depart-

ment of

History, University

of

Texas,

Austin.

Hager,

William H. 1963. The Plan of San

Diego:

Unrest on the Texas Border in 1915. Arizona

and the West 5:326-336.

Harris,

Charles H.

III,

and Louis R. Sadler. 1978. The Plan of San

Diego

and the Mexican-United

States War Crises of 1916: A Reexamination.

Hispanic

American Historical Review 58:381-408.

Hinojosa,

Gilberto. 1983. A Borderlands Town in Transition.

College

Station: Texas A&M Press.

Jameson,

Fredric. 1981. The Political Unconscious.

Ithaca,

N.Y.: Cornell

University

Press.

Lim6n,

Jose

E. 1974. El Primer

Congreso

Mexicanista de 1911: A Precursor to

Contemporary

Chicanismo. Aztldn 5:85-117.

. 1981. The Folk Performance of "Chicano" and the Cultural Limits of Political Ide-

ology.

In "And Other

Neighborly

Names": Social Process and Cultural

Image

in Texas

Folklore,

ed.

R. Bauman and R.

Abrahams,

pp.

197-225. Austin:

University

of Texas Press.

. 1983.

Folklore,

Social

Conflict,

and the United States-Mexico Border. In Handbook

of

American

Folklore,

ed. Richard

Dorson,

pp.

216-226.

Bloomington:

Indiana

University

Press.

.

1992. Mexican

Ballads,

Chicano Poems:

History

and

Influence

in Mexican-American Social

Poetics.

Berkeley: University

of California Press

(in press).

Longoria,

Mario D. 1982.

Revolution,

Visionary Plan,

and

Marketplace:

A San Antonio Inci-

dent. Aztldn 12:211-225.

McDowell,

John

H. 1981. The Corrido of Greater Mexico as

Discourse, Music,

and Event. In

"And Other

Neighborly

Names": Social Process and Cultural

Image

in Texas

Folklore,

ed. R. Bau-

man and R.

Abrahams,

pp.

44-75. Austin:

University

of Texas Press.

Montejano,

David. 1987.

Anglos

and Mexicans in the

Making of Texas,

1836-1986. Austin: Uni-

versity

of Texas Press.

Paredes,

Americo. 1958. "With His Pistol in His Hand": A Border Ballad and its Hero. Austin: Uni-

versity

of Texas Press.

1963. The

Ancestry

of Mexico's Corridos: A Matter of Definition.

Journal of

Amer-

ican Folklore 76:231-235.

. 1974.

Jose Mosqueda

and the Folklorization of Actual Events. Aztldn 4:1-30.

1976. A Texas-Mexican Cancionero. Urbana:

University

of Illinois Press.

1979. The Folk Base of Chicano Literature. In Modern Chicano Writers: A Collection

of

Critical

Essays,

ed.

Joseph

Sommers and

Tomais Ybarra-Frausto,

pp.

4-17.

Englewood

Cliffs, N.J.:

Prentice-Hall.

Pefia,

Manuel. 1982.

Folksong

and Social

Change:

Two Corridos as

Interpretive

Sources. Aztldn

13:13-42.

1985. The Texas-Mexican

Conjunto: History of

a

Working

Class Music. Austin: Uni-

versity

of Texas Press.

Richmond,

Douglas

W. 1980. La Guerra de Texas se renova: Mexican Insurrection and Carran-

cista

Ambitions,

1900-1920. Aztldn 11:1-32.

Saldivar, Ram6n.

1990. Chicano Narrative: The Dialectics

of Difference.

Madison:

University

of

Wisconsin Press.

Webb,

Walter Prescott. 1965

[1935].

The Texas

Rangers.

Austin:

University

of Texas Press.

Weber,

DavidJ.,

ed. 1973.

Foreigners

in their Native Land.

Albuquerque: University

of New Mex-

ico Press.

Weeks,

O. Douglas.

1929. The

League

of United Latin American Citizens: A Texas-Mexican

Civic

Organization.

Southwestern Political and Social Science

Quarterly

3:257-278.

William~s, Raymond. 1977. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford

University

Press.

1981. The

Sociology of

Culture. New York: Schocken Books.

180

Journal of

American Folklore 105

(1992)

Appendix

"Los Sediciosos"

1. En

mil

novecientos

quince,

iqu6

dias tan calurosos!

voy

a cantar estos

versos,

versos de los sediciosos.

2. Ya con 6sta van tres veces

que

sucede

lo bonito,

la

primera

fue en

Mercedes,

en Br6nsvil

y

en San Benito.

3. En ese

punto

de

Norias

ya

merito les

ardia,

a

esos rinches

desgraciados

muchas balas les

llovia.

4. Ya la mecha est-i encendida

por

los

puros

mexicanos,

y

los

que

van a

pagarla

son los

mexicotejanos.

5. Ya la mecha estai encendida

con azul

y

colorado,

y

los

que

van a

pagarla

van a ser los de este lado.

6. Ya la mecha

esti

encendida,

muy

bonita

y

colorada,

y

la vamos a

pagar

los

que

no debemos

nada.

7. Decia Aniceto

Pizafia,

en su caballo cantando:

-?D6nde

estain

por

ahi

los rinches?

que

los

vengo

visitando.

8. -Esos rinches de la

Kinefia,

dicen

que

son

muy

valientes,

hacen

ilorar

las

mujeres,

hacen correr a las

gentes.-

9. Decia Teodoro

Fuentes,

abrochlindose

un

zapato:

-A esos rinches de Kinefia

les daremos un mal rato.-

10. Decia Vicente el Giro

In nineteen hundred

fifteen,

Oh but the

days

were hot!

I am

going

to

sing

these

stanzas,

stanzas about the seditionists.

With this it will be three times

that remarkable

things

have

happened,

the first time was in

Mercedes,

then

in Brownsville and San Benito.

In that well-known

place

called

Norias,

it

really got

hot for

them;

a

great many

bullets rained down

on those cursed rinches.

Now the fuse is lit

by

the true-born

Mexicans,

and it will be the Texas-Mexicans

who will have to

pay

the

price.

Now the fuse is

lit,

in blue and

red,

and it will be those on this side who

will have to

pay

the

price.

Now the fuse is

lit,

very

nice and

red,

and it will be those of us who are

blameless who will have to

pay

the

price.

Aniceto Pizafio

said,

singing

as he rode

along,

"Where can I find

the rinches?

I'm here to

pay

them a visit.

"Those rinches from

King

Ranch

say

that

they

are

very

brave;

they

make the women

cry,

and

they

make the

people run."

Then said Teodoro

Fuentes,

as he was

tying

his

shoe,

"We are

going

to

give

a hard time to

those rinches from

King

Ranch."

Then said Vicente el

Giro,

Flores,

The Corrido and the

Emergence of

Texas-Mexican Social

Identity

181

en su chico caballazo:

-Echenme ese

gringo grande,

pa'llevairmelo

de brazo.-

11. Contesta el

americano,

con su sombrero en las manos:

-Yo sf me

voy

con

ustedes,

son

muy

buenos maxacanos.-

12. Decia

Miguel

Salinas

en su

yegiiita

almendrada:

-iAy, qu6 gringos

tan

ingratos!

que

no nos

hagan parada.-

13. En ese

punto

de

Norias

se ofa la

peloteria,

del sefior Luis de la Rosa

nomis el llanto se oia.

14. El Sefior Luis de la Rosa

se tenia

por

hombrecito,

a la hora de los balazos

Iloraba como un

chiquito.

15.

Decia Teodoro

Fuentes,

decia con su risita:

-Echen

balazos, muchachos,

iqu6

trifulca

tan bonita!

16.

-Tiren,

tiren

muchachitos,

tiren,

tiren de a

mont6n,

que

el Sefior Luis de la Rosa

ha manchado el

pabell6n.-

17. Gritaba Teodoro Fuentes:

-Hay que pasar por

Mercedes,

para

ensefiarle a los rinches

que

con nosotros no

pueden.--

18. Les dice Luis de la Rosa:

-Muchachos

qu6

van a hacer?

Por Mercedes no

pasamos,

y

si no lo van a

ver.--

19. Contesta Teodoro Fuentes

con su voz

muy

natural:

-Vale mis

que

usted no

vaya

porque

nomis va a llorar.-

20. Pues

pasaron por Mercedes,

sitting

on his

great big

horse,

"Let me at that

big Gringo,

so we can amble arm-in-arm."

The American

replies,

holding

his hat in his

hands,

"I will be

glad

to

go

with

you;

you

are

very good

Maxacans."

Then said

Miguel

Salinas,

on his almond-colored

mare,

"Ah,

how

disagreeable

are these

Gringos!

Why

don't

they

wait for us?"

In that well-known

place

called

Norias,

you

could hear the sound of

firing,

but from Sefior Luis de la

Rosa,

all

you

could hear was his

weeping.

Sefior Luis de la Rosa

considered himself a brave

man,

but at the hour of the

shooting,

he cried like a

baby.

Then said Teodoro

Fuentes,

smiling

his little

smile,

"Pour on the

bullets,

boys;

what a beautiful fracas!

"Fire,

fire

away, my boys;

fire,

fire all at

once,

for Sefior Luis de la Rosa

has besmirched his colors."

Teodoro Fuentes

shouted,

"We

have to

go through

Mercedes,

so we can show the rinches

that we are too

much for them."

Luis de la Rosa tells

them,

"Boys,

what are

you going

to do?

We cannot

go through

Mercedes,

and

if

you

doubt

it,

you

soon will

see."

Teodoro Fuentes

replies,

in a

very

natural voice,

"It's best that

you

not

go

with us,

because all

you

will do is

cry."

So

they

did

go through Mercedes,

182

Journal of

American Folklore 105

(1992)

y

tambidn

por

San

Benito,

iban a tumbar el tren

a ese

dipo

del Olmito.

21. Ya se van los

sediciosos,

ya

se van de

retirada,

de recuerdos nos

dejaron

una veta colorada.

22. Ya se van los sediciosos

y quedaron

de

volver,

pero

no

dijeron

cuando

porque

no

podian

saber.

23.

Despedida

no la

doy

porque

no la

traigo aqui,

se la llev6 Luis de la Rosa

para

San Luis Potosi.

and also

through

San

Benito;

they

went to derail the train

at the station of Olmito.

The seditionists are

leaving,

they

have

gone

into

retreat;

they

have left us a red swath

to remember them

by.

The seditionists are

leaving,

they

said that

they

would

return;

but

they

didn't tell us when

because

they

had no

way

of

knowing.

I will not

give you my

farewell,

because I did not

bring

it with

me;

Luis de la Rosa took it with him

to San Luis Potosi.

[as quoted

in Paredes

1976:71-73]

You might also like

- First Midterm Equation Sheet: Multiplicity Functions: Math Equations and ApproximationsDocument1 pageFirst Midterm Equation Sheet: Multiplicity Functions: Math Equations and ApproximationsKevin ChauNo ratings yet

- Equation SheetDocument2 pagesEquation SheetKevin ChauNo ratings yet

- Midterm Study GuideDocument39 pagesMidterm Study GuideKevin ChauNo ratings yet

- Keen MexicoDocument16 pagesKeen MexicoKevin ChauNo ratings yet

- ReadmeDocument2 pagesReadmeKevin ChauNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)