Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1975 - Comanor & Smiley, Monopoly & Distribution of Wealth

Uploaded by

linamkhan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

75 views19 pages"Although it is generally recognized that monopoly has distributive consequences, this factor is typically ignored by economists who examine the economic impact of monopoly..."

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document"Although it is generally recognized that monopoly has distributive consequences, this factor is typically ignored by economists who examine the economic impact of monopoly..."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

75 views19 pages1975 - Comanor & Smiley, Monopoly & Distribution of Wealth

Uploaded by

linamkhan"Although it is generally recognized that monopoly has distributive consequences, this factor is typically ignored by economists who examine the economic impact of monopoly..."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 19

Monopoly and the Distribution of Wealth

Author(s): William S. Comanor and Robert H. Smiley

Source: The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 89, No. 2 (May, 1975), pp. 177-194

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1884423 .

Accessed: 07/11/2013 14:12

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Quarterly

Journal of Economics.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

QUARTERLY JOURNAL

OF ECONOMICS

Vol. LXXXIX May 1975 No. 2

MONOPOLY AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH *

WILLIAM S. COMANOR

ROBERT H. SMILEY

A model of monopoly and wealth, 178. - Estimation of parameters, 182.-

The empirical findings, 189.- Conclusions, 194.

Although it is generally recognized that monopoly has distribu-

tive consequences, this factor is typically ignored by economists who

examine the economic impact of monopoly. Harberger, for example,

estimated the welfare costs of monopoly by subtracting monopoly

profits from the aggregate decline in consumer surplus and, on find-

ing this net loss to be small, concludes that, "we can neglect mo-

nopoly elements and still gain a very good understanding of how our

economic process works."

I

Similarly, it is argued that distributive

objectives should explicitly be ignored in the enforcement of anti-

monopoly policies.2 However, there have been few systematic studies

of the distributive effects of monopoly.

Our purpose is to estimate the impact of past and current enter-

prise monopoly profits on the distribution of household wealth in

the United States. We do not investigate here the various sources

of enterprise monopoly nor whether other desirable or undesirable

*

The authors are grateful to William F. Baxter, Marc J. Roberts, William

F. Sharpe, and George J. Stigler for helpful comments and suggestions. An

earlier version of this paper was presented at a Conference on Industrial

Organization, Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville, April 1973.

1. Arnold Harberger, "Monopoly and Resource Allocation," American

Economic Review, XLIV (May 1954), 77-87, quote on p.

87;

David R.

Kamerschen, "An Estimation of the Welfare Losses from Monopoly in the

American Economy," Western Economic Journal, IV (Summer 1966), 221-

36.

2. Oliver E. Williamson, "Economies as an Antitrust Defense," American

Economic Review, LVIII (March 1968), 18-35, esp p.

28;

Robert H. Bork,

"The Rule of Reason, and the Per Se Concept: Price Fixing and Market Divi-

sion," Yale Law Journal, LXXIV (April 1965), 775-847, esp. p. 839. See also

Richard Caves, American Industry: Structure, Conduct, Performance, 3rd

ed. (Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice Hall, 1972), especially p. 96.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

178 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

outcomes flow from them. Also we do not incorporate the effects

of excess returns, which take the form of higher input payments.

Furthermore, it should be noted that monopoly profits are those

returns that remain after deducting any costs of securing a mo-

nopoly position.3

Our focus on the distribution of wealth stems from the fre-

quently noted proposition that while monopolies extract excess pay-

ments from consumers, current owners often receive no excess re-

turns. Monopoly profits are generally capitalized into the value of

the firm at the time of the creation of the monopoly so that when

the current owners acquired their ownership rights, the price they

paid included the present value of the future stream of monopoly

returns. While the original owners of the monopoly gained, they

may have long since sold their ownership claims and therefore would

lose nothing if the monopoly was suddenly and unexpectedly dis-

solved. Wealth is created in the process of capitalizing monopoly

returns, and income gains take the form of a return on the wealth

created.

A MODEL OF MONOPOLY AND WEALTH

To isolate the distributive consequences of monopoly, we

estimate the wealth gain or loss due to monopoly for individual

wealth classes. These estimates are then subtracted from existing

wealth positions to determine hypothetical distributions of house-

hold wealth in the absence of monopoly. This procedure assumes

that the other determinants of this distribution remain unchanged.

Three basic assumptions are made. The first of these is that the

ratio of monopoly profits to gross national product has remained

constant throughout the period from 1890 through 1962. By mo-

nopoly profits we mean those profits in excess of the cost of capital,

which arise from differences between price and marginal costs that

are maintained in equilibrium. Monopolies, it is assumed, are

created and die in a steady state throughout these years.

The second assumption concerns the distribution of monopoly

gains. We assume that these gains are distributed in proportion to

current total business ownership claims. In other words, there is an

equal probability of realizing monopoly gains associated with each

3. It could be argued that, in equilibrium, the costs of securing monopoly

positions become sufficiently high so that, on balance, there are no monopoly

returns. While this may eventually be so in some cases, it is unlikely that all

such rewards are immediately eliminated, and it is the

impact

of the net

profits that remain in which we are interested.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONOPOLY AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH 179

claim on business ownership. This assumption might be rather con-

servative if all monopoly gains accrued to those who provide the

original capital for the monopoly, for the supply of such capital is

likely to be distributed even more unequally than are business

ownership claims overall. However, to the extent that monopolies

are created by relatively poor people, who own few business owner-

ship claims and who receive their ownership rights as returns to

entrepreneurial talent, the distribution of monopoly gains may be

distributed more equally across wealth classes.

Note that this assumption regarding the distribution by wealth

class of monopoly gains requires implicitly that these gains are high-

ly divisible among households. When monopoly gains take the form

of large indivisible blocs, they necessarily accrue ex post to mem-

bers of the highest wealth class. What becomes important in these

circumstances is the size of the bloc relative to average wealth

holdings in various classes rather than the original wealth of the

owners of the monopoly. Since our concern is with the influence

of monopoly on the current relative wealth positions of U.S. house-

holds, this assumption probably represents a conservative view of

the distribution of the ownership of monopoly gains.

The third assumption refers to the distribution across households

of excess monopoly payments. Monopoly leads to a redistribution

of income to the original owners of the firm from consumers who pur-

chase the output of the monopolist at higher prices than would have

prevailed had the industry been competitive. Therefore, we need

to be concerned with the distribution of excess payments, as well as

with the distribution of monopoly gains. We assume that the distri-

bution of excess monopoly payments is proportional to the distribu-

tion of total consumption expenditures. What is thereby required

is that rich and poor alike pay the same proportion of total con-

sumption expenditures in the form of monopoly payments.

In effect, this assumption requires that the elasticity of mo-

nopoly payments with respect to total consumption expenditures is

unity. To the extent that this elasticity exceeds unity, so that mo-

nopolized commodities comprise a larger share of consumption

ex-

penditures in relatively wealthy individuals, we overstate the effect

of monopoly on inequality.4 For this reason, we assume alterna-

tively that this elasticity is 1.5. In the latter case, outlays

on mo-

4. It might be argued alternatively that more wealthy consumers spend

relatively more of their income on services that are supplied under competi-

tive conditions. In this case the proportion

of income spent

on monopolized

commodities would decline as wealth increases,

and the

impact

of

monopoly

is understated.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

180 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

nopolized commodities are assumed to rise more than proportion-

ately with increases in total consumption expenditures.

We now proceed to a detailed description of a model that relates

the presence of monopoly returns to the distribution of wealth. Let

7rit(to-n)

be the annual flow of excess return after corporate taxes

due to monopoly in year t from monopolies created in year

(to-n).

The subscript i indicates that we are referring to that portion of

this flow which contributed to the wealth position of the original

owners who are members of the ith relative wealth class in year

(to-n).

Thus, what we mean by monopoly creation in this model

is the year in which monopoly returns are capitalized into the value

of the firm. In our notation,

to

is the current year, while n is the

number of years ago that monopoly gains were created and capital-

ized.

As indicated above, we assume that the life of a monopoly is

constant across all monopolies. Thus, monopolies generate excess

returns from year

(to-n)

to year (to-n+T-1) inclusive. This

represents a life of T years.

Let

Fit

be the flow of aggregate excess returns in year t that

supports the increased wealth of the original owners of the firm who

are members of the ith relative wealth class from all vintages of

monopoly in effect at that time. Thus,

T-1

( s) rt= 7rit (to -n) .

n=O

This summation runs over T years, since only these vintages con-

tribute to excess returns in years t.

Following our first assumption, we see that the flow of monop-

oly returns depends on the year received but not on the year that

the monopoly was created and capitalized. Moreover, these returns

are constant across vintages of monopoly for the same year received.

In other words, each of the T vintages in existence in any year

shares equally in the total monopoly returns received in that year.

On this basis,

T-1

(2)

>

7it(to-n)

=

Twit(to-n)

=1it.

n=O

Therefore,

7ri t

(3) tt(to0- )

=

-

Now let

Vito

be the wealth created by the capitalized monopoly

gains in the current year. This quantity is defined by

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONOPOLY AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH 181

(4)

N

[to-n+T-1

7Tjt (to...n)

](d)(1i 1.

rto-n~m

]

?n-=O [t to-n (1+i)J )(+)[ (-iMli

j

=t-

to+n

j=011,2,

T-1,

which, from expression (3), equals

(5)

Vito

=

Y

, li,

(1 -di) 11(1

+)"[-(- mli

n=-o t~t0-n (1?i)

i

i (

i

Here, di is the dissipation rate for members of the ith class from

accumulated wealth. (1-di)

is therefore the rate by which accu-

mulated wealth is carried forward by the ith wealth class from one

year to next. As indicated in expression (5), we assume that there

is no dissipation of capitalized monopoly gains in the first year

they are created. i is the appropriate interest rate.

rto-n+,m

is the

effective rate of taxation on capital gains for year

(to-n),

where

m is the number of years after capitalization that the tax is paid.5

Where capital gains are taxed when received, m equals zero. N is

the total number of years included in the analysis.

Turning now to the negative impact of monopoly on consum-

ers, let

7rTit(to-n)

be flow of excess expenditures due to monopoly

made by members of the ith class in year t to monopolies created in

year (to-n).

Therefore,

T-1

(6) 7rTj

it(to-n)-

n=O

7rTit

are

aggregate

excess

expenditures

made

by

members of the ith

wealth class in year t to all vintages of monopoly. Again, this sum

runs over T years, since excess expenditures are made only for those

vintages.

The wealth foregone in the current year by members of the ith

wealth class due to excess expenditures is indicated by

Iito,

which

equals

N

(7) iito

=

:i 7r1tq(to-n) Si (1-di) n( 1+i) ny

n=O

where si is the saving rate in the ith wealth class. This expression

indicates that only part of these excess expenditures would have been

saved during year t.

Now let

Wito

be total accumulated household wealth in the ith

5. Let the first term in square brackets be indicated by C. Then for each

value of n, expression (5) can be written as

[C(1+i)m(1-d,)m-rt,,n.~mC]

(1+i)-m (1-d,)n-m

which indicates, perhaps more clearly, the influence of capital gains taxation.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

182 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

wealth class in the current year, while

W*jt0

is the hypothetical

volume of wealth held by members of the ith wealth class in the

absence of the income transfers associated with monopoly. The dif-

ference between these two values equals

Vito-Iito,

which from the

above expressions equals

N

(8) Y,

[ (1-dj)nf(j+j)n]

n=O

{

to-n+T-1 7rit/T_(

1-

rto-n~m

)S7~~

{(t=-to-n

(I

+i)

)

(1 -di) m(1 +i)

m) (?)}

This expression can be simplified on the basis of the three as-

sumptions made above. First, let a be the proportion of GNP repre-

sented by monopoly profits, which is assumed constant over time.

Second, let pi be the proportion of business ownership claims held

by members of the ith wealth class in the current year. Third, let

p'.

be the

proportion

of total

consumption expenditures

made

by

members of the ith wealth class. These assumptions can be written

as

(9) 7rt=a GNPt

sit

=

Povrt

7rfit = Pi t.

With these assumptions, expression (8) equals

N

(10) E.

[ (1

-

di

)

( +i) n]

n=O

{aT (t

nYT-1 NI7 )(

1-

(1-d,)mn(l

j)m )-a p'jsi GNPto-n

As indicated, this expression describes the change in wealth

held by the ith wealth class due to the impact of past and present

monopoly. What is required to evaluate this expression are esti-

mates of a,

pi, p'i, si, di, rto-n+,?m,

and of course data on GNP. More-

over, a value of N must be chosen. Since the current year to for pur-

poses of this study is 1962, N is fixed at 72, which indicates that the

effects of monopoly since 1890 are included in our results. 1890 is

the year that the Sherman Antitrust Act was enacted into law. The

other required parameter is

T,

which is average monopoly life.

Since we have no way of estimating this factor, four alternate values

are chosen

-

ten years, twenty years, and forty years

-

and the

estimated effects of monopoly are reported for each.

ESTIMATION OF PARAMETERS

In this model we are concerned with the ratio of monopoly

profits to Gross National Product, and it is this ratio that is assumed

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONOPOLY AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH 183

constant over time. In a study of the price effects of monopoly,

Schwartzman 6 estimated that monopoly profits in manufacturing

were approximately 1 percent of Gross National Product in 1954.

Scherer

7

extended these results to reflect monopoly gains in other

sectors and suggested that aggregate monopoly profits are on the

order of 3 percent of GNP.8

Using a different methodology and for an earlier period, 1924-

1928, Harberger

9

estimated that total excess profits in the manu-

facturing sector but before corporate taxes were about

13/4

percent

of GNP. Corporate taxes during these years varied between 11

and 12 percent of net income,10 which suggests that excess profits

after taxes were about

11/2

percent of Gross National Product. If

monopoly accounted for two thirds of this quantity rather than

the one third asserted by Harberger, the ratio of monopoly profits

in manufacturing to GNP for 1924-1928 would be precisely the same

as that estimated by Schwartzman for 1954. In this case Scherer's

suggestion of a total figure of 3 percent might be appropriate for the

earlier period as well. All that can be concluded with much con-

fidence is that we are dealing with figures of the same order of mag-

nitude.

In the analysis below we use Scherer's estimate to determine

the impact of monopoly on the distribution of wealth. To be con-

servative, however, we also use an alternate estimate of 2 percent,

which probably represents a lower bound on the ratio of monopoly

profits of

GNP.'1

The interest rate used in our model is 8.4 percent, which is the

annual rate of return estimated by Lorie and Fisher 12 for an equal

investment in all common stocks listed on the New York Stock Ex-

change from January 1926 through December 1960. This is an after-

6. David Schwartzman, "The Effect of Monopoly on Price," Journal of

Political Economy, LXVII (Aug. 1959), 352-62, esp. 361.

7. F. M. Scherer, Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance,

(Chicago: Rand McNally, 1970), p. 409.

8. The corporate income tax rate has generally increased over time. To

the extent that it was lower during the early part of the period studied, the

use of end-period figures overstates the amount of taxes paid and understates

monopoly profits.

9. Harberger, op. cit., p. 83.

10. Ralph C. Epstein, Industrial Profits in the United States (New York:

National Bureau of Economic Research, 1937), pp. 624-34.

11. In an extensive study of monopoly in the consumer goods manufac-

turing sector recently completed by one of the authors, the total monopoly

transfer was estimated at 2.3 percent of aggregate value added in 'this sector.

William S. Comanor and Thomas A. Wilson, Advertising and Market Power

(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974).

12. J. H. Lorie and L. Fisher, "Rates of Return on Investment in Com-

mon Stocks," Journal of Business, XXXVII (Jan. 1964), 1-21.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

184 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

tax rate of return for a man in the $10,000 bracket in 1960. For

years prior to 1960 Lorie and Fisher apply a tax rate for someone

who held the same relative position in the income distribution. The

same rate is used for all wealth classes. Although tax rates are

higher for wealthier individuals, rates of return may also be higher

than for the rest of the population to the extent that unit costs of

obtaining investment information are lower.

The esimated values of

pi

are given in the second column in

Table I. As can be seen, the degree of inequality in the distribution

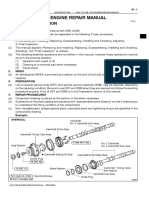

TABLE I

DISTRIBUTIONS OF NET WORTH, BUSINESS OWNERSHIP CLAIMS,

AND CONSUMPTION EXPENDITURES

1962

Percentage of

Percentage of Percentage of business Percentage of consumption

Wealth consumer units a ownership claims b net worth C expenditures

Class (1) (2) (3) (4)

1. 28.25 0.78 0 19.94

2. 17.33 2.07 2.41 15.38

3. 14.58 4.03 5.26 13.92

4. 22.30 11.96 17.74 23.52

5. 10.82 15.18 19.05 12.85

6. 4.28 14.54 14.84 6.60

7. 1.22 8.01 8.07 3.24

8. 0.95 15.71 14.09 2.49

9. 0.27 27.94 18.53 2.07

100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00

Totals may not add due to rounding.

a. Consumer units are ordered by net worth.

b. This distribution refers to wealth rather than net worth classes. Moreover, the first

class refers only to those households with positive wealth. Households with zero or negative

wealth are assumed to hold no business ownership claims.

c. The mean net worth of households in the first class is negative. For purposes of

this distribution the percentage figure is set at zero.

Sources: Dorothy S. Projector and Gertrude S. Weiss, Survey of Financial Characteris-

tics of Consumers, Federal Reserve Technical Paper, 1966; Dorothy S. Projector, Survey of

Changes in Family Finances, Federal Reserve Technical Paper, 1968.

of business ownership claims is even greater than that of the distri-

bution of net worth. Thus, the 158,000 consumer units with net

worth exceeding $500,000 are merely 0.27 percent of the total num-

ber of consumer units in the population but control 18.53 percent

of aggregate net worth. Moreover, they control nearly 30 percent

of total business ownership claims.

The top three classes in the distribution, those with net worth

exceeding $100,000, amount to 2.44 percent of the total number of

consumer units but control just over 40 percent of aggregate

net

worth and over 51 percent of total business ownership claims. The

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONOPOLY AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH 185

degree of inequality in business ownership claims is striking, even

though the indirect control of such claims through retirement plans

and life insurance assets is included in the total.13

In this model we use the same values of pi, applicable to 1962,

for every year since 1890. Whether this leads to an under- or over-

statement of the distributive effects of monopoly depends on what

has happened over time to the distribution of business ownership

claims. If this distribution were unchanged, no biases would be in-

troduced by this procedure. While there is no information available

on the distribution of business ownership claims in earlier years,

there are various estimates available of the distribution of wealth

in 1890.14 While there are discrepancies between the reported dis-

tributions, each of them shows a higher degree of inequality for

1890 than was the case in 1962. These results suggest thereby that

the distribution of wealth has become slightly less unequal in the

seventy-two years between 1890 and 1962.15

If the distribution of wealth has progressively become more

equal since 1890, it is probable that the distribution of business

ownership claims has similarly become more equal. In this case the

vector of pi in 1962 probably understates the degree of inequality

in the distribution of business ownership claims in earlier years.

To this extent the use of constant

pi's

based on 1962 data should

understate the true impact of monopoly in inequality in the distri-

bution of wealth.

A vector of

p'i

is also used in our estimating model. These

parameters are founded on the relative distribution of consumption

expenditures by net worth classes and are given in the fourth

13. The following claims are included in this definition: business or pro-

fession assets, beneficial interest in trust, all publicly traded stock, investment

in real estate, business not managed by unit, life insurance assets, and retire-

ment plans.

14. See Charles V. Spahr, An

Essay

on the Present Distribution of Wealth

in the United States (New York, 1896); W. I. King, The Wealth and Income

of the People of the United States (New York: Macmillan,

1915); George K.

Holmes, "The Concentration of Wealth," Political Science

Quarterl4y, VIII

(Sept. 1893), 589-600; Robert E. Gallman, "Trends in the Size Distribution of

Wealth in the Nineteenth Century: Some Speculations," Six Papers on the

Size Distribution of Wealth and Income, Lee Soltow, ed. (New York: Colum-

bia University Press, 1969).

15. This conclusion is consistent with Lampman's finding that the pro-

portion of wealth held by the top 2 percent of families in the United States

declined slightly from 1922 to 1953. Robert J. Lampman, The Share of Top

Wealth-Holders in National Wealth, 1922-1956 (Princeton: Princeton Uni-

versity Press, 1962). Pryor also notes that the inequality of wealth has de-

clined since the turn of the century. Frederick L. Pryor, "Simulation of the

Impact of Social and Economic Institutions on the Size Distributions of In-

come and Wealth," American Economic Review, LXIII (March 1973), 50-72,

esp. 66.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

186 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

column in Table I. This distribution is also somewhat unequal, in

that the most wealthy 2.4 percent of the nation's households ac-

count for nearly 8 percent of total consumption expenditures. How-

ever, as can be seen, consumption expenditures are distributed far

more equally than either net worth or business ownership claims.

Indeed, it is the considerable discrepancy between the distributions

in columns (2) and (4) that suggests that monopoly may have a

major impact on the degree of inequality in the distribution of

wealth. If these distributions were identical, there would be little

impact. Again, we use the distribution for 1962 for all preceding

years.'6

We also require an estimate of

si,

which is the saving ratio from

disposable income. While there are different approaches to the

estimation of this parameter, it is often argued that the proportion

of income saved is independent of income.'7 Consistent with this

view, we use the same saving ratio for all wealth classes. Moreover,

since there is some evidence that saving ratios have been fairly con-

stant over time in the United States, we use the same ratio for each

year in the analysis.'8 The ratio, which is estimated from data for

1963, is 16.6 percent.19

As noted above,

di

is the proportion of aggregate wealth held

by members of the ith relative net worth class that is dissipated in a

given year. The dissipation of accumulated wealth has two com-

ponents: first, dissipation that takes place during the lifetime of the

members of the family; and second, dissipation that takes place at

the death of one or more members of the family.20 The first element

of

di

is the ratio of aggregate dissaving to aggregate wealth within

the ith class. This component of

di

is readily estimated from avail-

able data.

16. Since the distribution of income has become somewhat more equal

since 1890, this procedure understates the correct volume of consumption ex-

penditures in earlier years by the more wealthy households. As a result, these

households probably have made a larger share of excess payments due to

monopoly than is accounted for by these estimates.

17. Franco Modigliani and Richard Brumberg, "Utility Analysis and the

Consumption Function: An Interpretation of Cross-Section Data," Post-

Keynesian Economics, Kenneth K. Kurihara, ed. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rut-

gers University Press, 1955), p. 430.

18. After an extensive analysis of saving behavior between 1896 and 1949,

Goldsmith reports "long-term stability of aggregate personal saving at approx-

imately one-eighth of income" (R. W. Goldsmith, A Study of Saving in the

United States; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955, Vol. I., p. 22).

19. Note that in this model a high saving ratio tends to reduce the effect

of monopoly on the distribution of wealth.

20. Business losses can be viewed as a source of the dissipation of wealth.

However, the interest rate used in this study includes the effects of business

losses as well as gains. To include the former therefore would represent double

counting.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONOPOLY AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH 187

Estimates of

di

for 1963 are used throughout, and we need to

consider what biases are thus created. One approach to this prob-

lem is in terms of a "life cycle" theory of savings. As summarized by

Lydall,21 savings increase with incomes from marriage through

middle age. At retirement, however, incomes fall, and capital is

drawn down to maintain levels of consumption.22 In this approach

dissaving takes place largely among households headed by retired

people. To the extent, then, that the proportion of such households

has increased over time, as appears to be the case,23 dissaving rates

are likely to be higher at the end of the period studied than earlier,

and the impact of monopoly is understated.

This argument must be qualified, however, in important re-

spects. While households in 1963 with head sixty-five and over

have a larger ratio of aggregate dissaving to aggregate wealth than

those headed by persons between thirty-five and sixty-four, they

account for only 31 percent of aggregate dissaving. The reason is

that they comprise only 19 percent of total consumer units. While

households headed by younger people have lower dissaving rates,

they are sufficiently numerous that they account for over two thirds

of total dissaving. However, there is some indication that the find-

ing of a general constancy of saving behavior applies also to dis-

saving rates.24 In this case current rates by age group are appro-

priate for earlier years. Furthermore, an increase in the proportion

of consumer units headed by older people still suggests an increase in

overall dissavings rates. What is implied thereby is that 1963 values

of

di,

if anything, overstate true values for earlier years.

The second element of wealth dissipation takes place on the

death of adult members of a family. The important components of

estate taxes, funeral expenses, administrative expenses, and chari-

table contributions at the time of death are determined for 1962.

Again, this component of

di

is assumed constant over time. To some

extent, this approach is a conservative one since estate taxes were a

good deal lower in the early years of the century, although the im-

21. Harold Lydall, "The Life Cycle in Income Saving, and Asset Owner-

ship," Econometrica, XXIII (April 1955), 149, 150.

22. See also Modigliani and Brumberg, op. cit.;

and Albert Ando and

Franco Modigliani, "The 'Life Cycle' Hypothesis of Saving," American Eco-

nomic Review, LIII (March 1963), 55-84.

23. Goldsmith (op. cit., p. 17) reports that "during the fifty years since

the turn of the century the length of the retirement period has shown a rising

trend, reflecting earlier retirement as well as increased longevity."

24. After reviewing various surveys of family income and expenditures

from 1888 to 1952, Brady finds that "the relative number of families ending the

year with a surplus (net saving) or a deficit (net dissaving) shows very little

tendency to vary with the date, the place, or the population group." Dorothy

S. Brady, "Family Saving 1888 to 1950," Goldsmith, op. cit., Vol. III, p. 143.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

188 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

portance of these taxes has declined somewhat since the Second

World War.25

A final element in the dissipation of accumulated wealth is

legacies made at death. In cases where a family has only a single

child or where it practices primogeniture, legacies create no prob-

lems for this analysis. The wealth of the parents is passed on to a

single child, so that in effect, the family remains intact. Where, on

the other hand, there is more than one child in the family and primo-

geniture is not practiced, so that household wealth is divided among

a number of children, there is some prospect that the children will

fall in a lower wealth class than did the parents. In this case what

occurs is not really the dissipation of household wealth as in the

case of, say, estate taxes, but rather a process by which the distribu-

tion becomes more equal.26

While there is little empirical evidence available on the effect

of inheritance on the distribution of wealth, some partial evidence

has been gathered by Projector and Weiss.27 While their data are

far from conclusive, they suggest that inheritances account for a

much higher proportion of total wealth among the wealthiest 2.4

percent of total households, which are those with wealth exceeding

$100,000 in 1962, than among the remaining 97.6 percent. More-

over, it is only among the three most wealthy classes, and perhaps

also the fourth highest, that inherited assets account for more than

a "small" proportion of the total. What this suggests is that the

division of estates into two or more parts at death may increase the

degree of equality in the distribution of wealth among the richest 2

percent or perhaps 6 percent of the; total number of households in

the country, but has little impact on the distribution of wealth be-

tween the top 4 to 6 percent and the bottom 94 or 96 percent.28

Once created, large wealth positions are likely to be maintained

within the top 2 to 6 percent of the distribution, so that the equaliz-

ing effect of inheritances across this boundary may be relatively

small. While we need to be wary of imputing too much importance

25. Lampman, op. cit., pp. 238-39.

26. The importance of this factor is examined by J. E. Stiglitz, "Distribu-

tion of Income and Wealth Among Individuals, Econometrica, XXXVII

(July 1969), 382-97;

and Pryor, op. cit.

27. Dorothy S. Projector

and Gertrude S. Weiss, Survey of Financial

Characteristics of Consumers, Federal Reserve Technical Paper, 1966, pp. 148,

151.

28. There is some further indication that, except for the very wealthy, in-

heritances account for a small share of changes in average net worth. John B.

Lansing and John Sonquist, "A Cohort Analysis of Changes in the Distribution

of Wealth," Soltow, op. cit., pp. 64-67.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONOPOLY AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH 189

to a few scattered pieces of evidence, it may be that our results are

not greatly distorted by ignoring this component of

di.

Finally, we need to determine rates of capital gains taxation.

The rate of taxation on accrued capital gains can be viewed as com-

posed of two elements: the capital gains tax rate on realized capital

gains and the ratio of realized gains to accrued gains. This latter

factor is particularly important, since it is estimated that 84 per-

cent of total accrued capital gains on all corporate shares listed on

the New York Stock Exchange since 1922 had not been taxed by

1963.29 Since there is no reason to believe that this figure is differ-

ent in the years from 1913, when the income tax was reintroduced

into the United States, through 1921, we shall be concerned only with

the remaining 16 percent of accrued capital gains. For this 16 per-

cent we assume that these gains are realized and taxed as soon as

possible after accrual, consistent with the tax advantages of post-

poning their realization in effect at the time.30 In some years various

steps were introduced into the tax laws so that it was advantageous

to hold the unrealized gains for from one to six years. This optimal

rate of postponement, indicated by m, is also used in the analysis.3'

THE EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

The current and resulting distributions arising from the model

and estimates described above are given in Table II. The resulting

distributions here are founded on Scherer's estimate that monopoly

profits after taxes are 3 percent of Gross National Product. From

these results it appears that the presence of past and current monop-

oly has had a major impact on the degree of inequality in the cur-

rent distribution of household wealth. The size of this effect,

how-

ever, is influenced by what is assumed regarding the average life of

a monopoly. In our model longer monopoly lives indicate that re-

turns from monopoly are spread over longer periods of time. There-

fore, the longer the assumed monopoly life, the smaller the impact of

monopoly on the distribution of wealth. This

relationship

is due

to our permitting monopoly lives to vary while holding constant

the total volume of monopoly profits.

The results presented here are striking.

The most wealthy size

29. Martin David, Alternative Approaches to Capital Gains Taxation

(Washington: Brookings Institution, 1968), p. 96.

30. In this we ignore the benefits of postponing tax to receive interest

on the tax payment.

31. Data on rates of capital gains taxation were gathered from Anita

Wells, "Legislative History of Treatment of Capital Gains Under Federal

Income Tax, 1913-1948," National Tax Journal, II (March 1949), 12-32.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

190 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

= ~ ~

r C) t- to T t- s c 0 ) t Io CD

S; ~~o o M qg c r

-

x~~~~~ C; 3Z C E;G

~~~~~~~~C1i bb1 M N 00 1 Q O

;~~~~~~~~~~c (::o c C6~ ; 6c

0 Ho

0 -t C )

P;4 ce

E-

Eo

q

r-

o

S

c: rZc cq t- c oo x6 ao6 ci , :

Is~W nte

0

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONOPOLY AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH 191

class refers to all households with net worth exceeding a half million

dollars at the end of 1962. As indicated, these households account

for 0.27 percent of the total number of households. Currently, they

control 18.5 percent of total household wealth. In the absence of

monopoly and under the conditions of this model, their share of

total wealth would fall to between 3 and 10 percent of the total.

Even if we take the midpoint of this range, the share of total wealth

accounted for by the most wealthy members of society would de-

cline by nearly two thirds.

The results are somewhat less striking but still significant if

we look at the top three size classes together: those with household

wealth exceeding $100,000 in 1962. These households account for

about 2.4 percent of the total households in the country. Currently

they account for slightly more than 40 percent of total wealth. In

the absence of monopoly their share of aggregate wealth would lie

somewhere between 16.6 percent and 27.5 percent, which would

represent a decline of nearly 50 percent in their share of total house-

hold wealth.

At the bottom end of the distribution, households would be rel-

atively better off in the absence of monopoly. The mean net worth

of the bottom 28 percent would now be positive. Indeed, these re-

sults suggest that the relative wealth position of 93.3 percent of the

total households in the country would be improved in the absence

of monopoly.

The estimated impact of monopoly is sufficiently strong to re-

duce the average wealth position of members of the sixth wealth class

to a lower relative position when ten- and twenty-year monopoly

lives are assumed. As a result, the hypothetical distributions given

in those cases are not true frequency distributions but rather repre-

sent estimated relative wealth positions for households currently

in the positions given. For this reason, our primary focus must be

on the relative position of the most wealthy one or three classes in

the distribution in 1962.

While Scherer's estimate of 3 percent of monopoly profits seems

reasonable, we also investigate the impact of monopoly on the dis-

tribution of wealth under the alternate assumption that they ac-

count for only 2 percent of Gross National Product. The results

are given in Table III.

Since monopoly is less important here, its impact on the distri-

bution of wealth is reduced. Under these assumptions, the wealthi-

est 0.27 percent of the nation's households would account for about

13 percent of aggregate household net worth in the absence of mo-

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

192 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

0 cd-c.t~oo

S~~~~~C t- 6 rf eC c

> z C t ots~~~sn o M C

r-l

0Y Cc0 d c0 m0

a 09~~~~- ttS

km U m 00 0cl 00 C9 km I- O

d

0V rln

:

cq, 4 oo

cr

<o.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONOPOLY AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF WEALTH 193

nopoly as compared with 18.5 percent currently. The effect of

monopoly has thereby been to increase the relative share of house-

hold wealth held by the nation's wealthiest families by something

over 40 percent.

The wealthiest 2.4 percent of the total number of households now

accounts for slightly more than 40 percent of total wealth. In the

absence of monopoly their share would fall to approximately 32

percent. The effect of monopoly has thereby been to increase the

relative wealth holdings of these families by about 20 percent. Fur-

thermore, it can be observed that mean wealth holdings of the

bottom 28 percent of families are again positive in the absence of

monopoly.

What seems apparent from this analysis is that the major im-

pact of monopoly lies in its effect on the relative wealth holdings

of the very wealthy: those with household net worth exceeding a

half million dollars in 1962. In the absence of monopoly their rela-

tive wealth positions would be much reduced.

From the statistics presented in Tables II and III, we can de-

rive Lorenz curves, which describe the degree of inequality in the

current distribution of household net worth as well as for the eight

alternate distributions. What is interesting about these Lorenz

curves is that there is a complete nesting among the various curves.

None of the curves intersects with any other. The Lorenz curves

found by assuming monopoly profits at 2 percent of GNP lie inside

the current Lorenz curve, while the four curves derived by assuming

that monopoly profits are 3 percent of GNP lie closest to the diag-

onal. This property is important for it means that whichever sum-

mary measure of inequality is chosen, the same ranking of distribu-

tions is preserved.

Resulting distributions of household net worth were also com-

puted on the alternate assumption that the elasticity of outlays

on

monopolized products with respect to total expenditures equals 1.5.

In this case expenditures on monopolized products are assumed to

increase sharply as total consumption expenditures

increase. When

these distributions were obtained, however, it was found that they

were very similar to those computed on the basis of our original

as-

sumption. In no case did the proportion of household net worth ac-

counted for by a specific size class differ from the corresponding

figure presented in Tables II or III by as much as a

single percentage

point. We concluded therefore that our findings

were not greatly

influenced by our original assumption regarding the distribution of

expenditures on monopolized products.

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

194 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

CONCLUSIONS

Monopoly gives rise to a stream of excess payments by con-

sumers, which extends over time and which is generally capitalized

by the original owners of the firm. It thereby contributes to the

process of wealth creation. In this paper we provide a model of this

process, which is then used to estimate the effect of monopoly on the

distribution of household wealth in the United States. Using this

model, we find that past and current monopoly has had a major im-

pact on the current degree of inequality in this distribution. While

we do not pretend that our estimates are accurate to a high degree

of precision, we believe that these results represent appropriate or-

ders of magnitude. Throughout, we have tried to be conservative so

as to understate the true impact of monopoly.

To be sure, these results depend crucially on the assumptions

and parameter estimates on which our model is founded. What seems

clearly required is further empirical research on these matters. In

particular, we need to know a good deal more about the size and

pattern of ownership of newly capitalized monopoly gains. In addi-

tion, we need to look more broadly at the many distributional con-

sequences of various forms and dimensions of monopoly. Only in

this manner can a sharper picture be obtained.

Despite the primary concern of economists with the resource

allocation effects of market arrangements, political officials are more

often concerned with distributive effects. More research on the

latter issue is therefore required to provide a more stable founda-

tion for policy judgments.

UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO

CORNELL UNIVERSITY

This content downloaded from 209.66.96.84 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 14:12:59 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy For ProfitDocument74 pagesLooting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy For Profit1080 GlobalNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:17:18 +00:00Document74 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:17:18 +00:00skywardsword43No ratings yet

- The Causes and Effects of Mandated Accounting Standards: SFAS No. 94 As A Test of The Level Playing Field TheoryDocument23 pagesThe Causes and Effects of Mandated Accounting Standards: SFAS No. 94 As A Test of The Level Playing Field TheoryInna MuthmainnahNo ratings yet

- Ans 1 Walras' Law Is A Principle In: General Equilibrium Theory Excess Market DemandsDocument7 pagesAns 1 Walras' Law Is A Principle In: General Equilibrium Theory Excess Market DemandskoolzubNo ratings yet

- The Econometric SocietyDocument24 pagesThe Econometric Societysara diazNo ratings yet

- Maskin y Riley - Monopoly With Incomplete Information - 1984 PDFDocument27 pagesMaskin y Riley - Monopoly With Incomplete Information - 1984 PDFFernando FCNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Dividend Yield and DivideDocument22 pagesThe Effects of Dividend Yield and DividesandygtaNo ratings yet

- Eberly (1994) PDFDocument35 pagesEberly (1994) PDFwololo7No ratings yet

- Eberly (1994)Document35 pagesEberly (1994)wololo7No ratings yet

- Diamond, P. A., & Mirrlees, J. A. (1971) - Optimal Taxation and Public Production I, Production EfficiencyDocument21 pagesDiamond, P. A., & Mirrlees, J. A. (1971) - Optimal Taxation and Public Production I, Production EfficiencyGerald HartmanNo ratings yet

- SCDL - PGDBA - Finance - Sem 1 - Managerial EconomicsDocument16 pagesSCDL - PGDBA - Finance - Sem 1 - Managerial Economicsapi-376241950% (2)

- Dividend Policies in An Unregulated Market: The London Stock Exchange 1895-1905Document24 pagesDividend Policies in An Unregulated Market: The London Stock Exchange 1895-1905Binju SBNo ratings yet

- Catering Theory by Baker & WurglerDocument42 pagesCatering Theory by Baker & Wurglerarchaudhry130No ratings yet

- Jofi12082hyfrtd F FDocument45 pagesJofi12082hyfrtd F FAlexandru DobrieNo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Secondary Education - Social Studies - Set C: Activity in MicroeconimicsDocument4 pagesBachelor of Secondary Education - Social Studies - Set C: Activity in MicroeconimicsDave EscalaNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure, Cost of Capital, and Voluntary Disclosures ModelDocument51 pagesCapital Structure, Cost of Capital, and Voluntary Disclosures ModelKetz NKNo ratings yet

- Oxford University Press The Quarterly Journal of EconomicsDocument18 pagesOxford University Press The Quarterly Journal of Economicssanjay shamnaniNo ratings yet

- Income & EnterpreneureDocument34 pagesIncome & EnterpreneurerajkumardepalNo ratings yet

- Golden Eggs and Hyperbolic DiscountingDocument35 pagesGolden Eggs and Hyperbolic DiscountingEtelvina Stefani ChavezNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure Changes and Security PricesDocument45 pagesCapital Structure Changes and Security Prices(FPTU HCM) Phạm Anh Thiện TùngNo ratings yet

- Laffont y Tirole 1991 764959Document45 pagesLaffont y Tirole 1991 764959osiris reyesNo ratings yet

- University of Chicago Journal Article on Vertical IntegrationDocument31 pagesUniversity of Chicago Journal Article on Vertical IntegrationTouhid AkramNo ratings yet

- Consumer Bankruptcy: A Fresh StartDocument36 pagesConsumer Bankruptcy: A Fresh StartHerta PramantaNo ratings yet

- Manitou MLT X 735 741 1035 120 Lsu T Ps Serie 6 E3 Operators Manual 647121ruDocument22 pagesManitou MLT X 735 741 1035 120 Lsu T Ps Serie 6 E3 Operators Manual 647121rudebracampbell120496mwb100% (115)

- NotesDocument17 pagesNotesKripaya ShakyaNo ratings yet

- Nonprofit Versus Profit Firms in The Performing Arts: Edwin G. WestDocument11 pagesNonprofit Versus Profit Firms in The Performing Arts: Edwin G. WestarthurhfmoNo ratings yet

- SM Econ 05 Micro Ch05Document24 pagesSM Econ 05 Micro Ch05senrucatNo ratings yet

- Ownership 7 16Document54 pagesOwnership 7 16aliNo ratings yet

- HarBurger 1954Document12 pagesHarBurger 1954YuGin LinNo ratings yet

- Do Dividend Clienteles Exist? Evidence On Dividend Preferences of Retail InvestorsDocument33 pagesDo Dividend Clienteles Exist? Evidence On Dividend Preferences of Retail Investorsandresitocano1988No ratings yet

- Pension Liabilities: Fear Tactics and Serious PolicyDocument22 pagesPension Liabilities: Fear Tactics and Serious PolicyCenter for Economic and Policy ResearchNo ratings yet

- Oxford University Press The Quarterly Journal of EconomicsDocument11 pagesOxford University Press The Quarterly Journal of EconomicsDarrelNo ratings yet

- Bergson 1973Document19 pagesBergson 1973Angel GuillenNo ratings yet

- Wiley American Finance AssociationDocument40 pagesWiley American Finance AssociationAdnan KamalNo ratings yet

- Merger and AcquisitionDocument7 pagesMerger and AcquisitionNishant JainNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics Chapter 12Document35 pagesManagerial Economics Chapter 12anmanmanmNo ratings yet

- The Econometric SocietyDocument24 pagesThe Econometric Societyaria woohooNo ratings yet

- Imp Finance and economics termsDocument55 pagesImp Finance and economics termsRaman KumarNo ratings yet

- ViveseconometricaDocument56 pagesViveseconometricaFabian GouretNo ratings yet

- Me, Unit 1Document4 pagesMe, Unit 1Bishnudeo PrasadNo ratings yet

- Limited Liability PrincipleDocument20 pagesLimited Liability Principleapi-308105056100% (2)

- Liquidity Preference As Behavior Towards Risk Review of Economic StudiesDocument23 pagesLiquidity Preference As Behavior Towards Risk Review of Economic StudiesCuenta EliminadaNo ratings yet

- Demsetz & Lehn 1985Document24 pagesDemsetz & Lehn 1985nicodimoana100% (1)

- Valuation in Dot Com BubbleDocument31 pagesValuation in Dot Com BubblePranav ShandilNo ratings yet

- Optimal Capital Accumulation and Corporate Investment BehaviorDocument31 pagesOptimal Capital Accumulation and Corporate Investment BehaviorichaNo ratings yet

- Financial Markets and InstitutionsDocument23 pagesFinancial Markets and InstitutionsJocelyn Estrella Prendol SorianoNo ratings yet

- Endogenous Credit CyclesDocument27 pagesEndogenous Credit CyclesJonas SiqueiraNo ratings yet

- Hart CostsBenefitsDocument30 pagesHart CostsBenefitsArko MukhopadhyayNo ratings yet

- kinh te vi mo dichDocument28 pageskinh te vi mo dichtho.tnm.62ktptNo ratings yet

- Allen 2000Document38 pagesAllen 2000meri annisaNo ratings yet

- Natural Resources 2Document11 pagesNatural Resources 2Juma KomboNo ratings yet

- Kaldor - 1939 - Speculation and Economic StabilityDocument28 pagesKaldor - 1939 - Speculation and Economic Stabilityjpkoning100% (1)

- W 25578Document29 pagesW 25578jigarchhatrolaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document13 pagesChapter 3affy714No ratings yet

- Two Models of Land Overvaluation and Their Implications: October 2010Document33 pagesTwo Models of Land Overvaluation and Their Implications: October 2010JaphyNo ratings yet

- CALABRESI, Guido, Some Thoughts On Risk Distribution and The Law of TortsDocument56 pagesCALABRESI, Guido, Some Thoughts On Risk Distribution and The Law of TortsGabriel CostaNo ratings yet

- The Valuation of Distressed CompaniesDocument22 pagesThe Valuation of Distressed Companiessanjiv30100% (1)

- 4 MicroeconomicsDocument33 pages4 MicroeconomicsSoumyadip RoychowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Principles Of Political Economy Abridged with Critical, Bibliographical, and Explanatory Notes, and a Sketch of the History of Political EconomyFrom EverandPrinciples Of Political Economy Abridged with Critical, Bibliographical, and Explanatory Notes, and a Sketch of the History of Political EconomyNo ratings yet

- GASB 34 Governmental Funds vs Government-Wide StatementsDocument22 pagesGASB 34 Governmental Funds vs Government-Wide StatementsLisa Cooley100% (1)

- Device Exp 2 Student ManualDocument4 pagesDevice Exp 2 Student Manualgg ezNo ratings yet

- Get 1. Verb Gets, Getting Past Got Past Participle Got, GottenDocument2 pagesGet 1. Verb Gets, Getting Past Got Past Participle Got, GottenOlga KardashNo ratings yet

- The Serpents Tail A Brief History of KHMDocument294 pagesThe Serpents Tail A Brief History of KHMWill ConquerNo ratings yet

- Inline check sieve removes foreign matterDocument2 pagesInline check sieve removes foreign matterGreere Oana-NicoletaNo ratings yet

- Tong RBD3 SheetDocument4 pagesTong RBD3 SheetAshish GiriNo ratings yet

- Relations of Political Science with other social sciencesDocument12 pagesRelations of Political Science with other social sciencesBishnu Padhi83% (6)

- Science 10-2nd Periodical Test 2018-19Document2 pagesScience 10-2nd Periodical Test 2018-19Emiliano Dela Cruz100% (3)

- Speech Writing MarkedDocument3 pagesSpeech Writing MarkedAshley KyawNo ratings yet

- EE-LEC-6 - Air PollutionDocument52 pagesEE-LEC-6 - Air PollutionVijendraNo ratings yet

- Year 11 Economics Introduction NotesDocument9 pagesYear 11 Economics Introduction Notesanon_3154664060% (1)

- Chronic Pancreatitis - Management - UpToDateDocument22 pagesChronic Pancreatitis - Management - UpToDateJose Miranda ChavezNo ratings yet

- B2 WBLFFDocument10 pagesB2 WBLFFflickrboneNo ratings yet

- PIA Project Final PDFDocument45 pagesPIA Project Final PDFFahim UddinNo ratings yet

- Arx Occasional Papers - Hospitaller Gunpowder MagazinesDocument76 pagesArx Occasional Papers - Hospitaller Gunpowder MagazinesJohn Spiteri GingellNo ratings yet

- Battery Genset Usage 06-08pelj0910Document4 pagesBattery Genset Usage 06-08pelj0910b400013No ratings yet

- Introduction to History Part 1: Key ConceptsDocument32 pagesIntroduction to History Part 1: Key ConceptsMaryam14xNo ratings yet

- 12.1 MagazineDocument44 pages12.1 Magazineabdelhamed aliNo ratings yet

- Topic 4: Mental AccountingDocument13 pagesTopic 4: Mental AccountingHimanshi AryaNo ratings yet

- Architectural PlateDocument3 pagesArchitectural PlateRiza CorpuzNo ratings yet

- How To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationDocument3 pagesHow To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationHenry SilvaNo ratings yet

- Data FinalDocument4 pagesData FinalDmitry BolgarinNo ratings yet

- The Awesome Life Force 1984Document8 pagesThe Awesome Life Force 1984Roman PetersonNo ratings yet

- Aladdin and the magical lampDocument4 pagesAladdin and the magical lampMargie Roselle Opay0% (1)

- 2C Syllable Division: Candid Can/dDocument32 pages2C Syllable Division: Candid Can/dRawats002No ratings yet

- Bpoc Creation Ex-OrderDocument4 pagesBpoc Creation Ex-OrderGalileo Tampus Roma Jr.100% (7)

- 2020 Book WorkshopOnFrontiersInHighEnerg PDFDocument456 pages2020 Book WorkshopOnFrontiersInHighEnerg PDFSouravDeyNo ratings yet

- NAZRUL - CV ChuadangaDocument2 pagesNAZRUL - CV ChuadangaNadira PervinNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Family Background and Academic Performance of Secondary School StudentsDocument57 pagesThe Relationship Between Family Background and Academic Performance of Secondary School StudentsMAKE MUSOLININo ratings yet

- College Wise Form Fillup Approved Status 2019Document4 pagesCollege Wise Form Fillup Approved Status 2019Dinesh PradhanNo ratings yet