Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: Differentiation Patterns and Immunohistochemical Features - A Mini-Review and Our New Findings

Uploaded by

Afkar300 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

24 views7 pagesMalignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) represent a group of highly heterogeneous human malignancies. The differential diagnosis of MPNST from other spindle cell neoplasms poses great challenges for pathologists. This report provides a mini-review of these unique features associated with MPNST.

Original Description:

Original Title

v03p0303

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMalignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) represent a group of highly heterogeneous human malignancies. The differential diagnosis of MPNST from other spindle cell neoplasms poses great challenges for pathologists. This report provides a mini-review of these unique features associated with MPNST.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

24 views7 pagesMalignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: Differentiation Patterns and Immunohistochemical Features - A Mini-Review and Our New Findings

Uploaded by

Afkar30Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) represent a group of highly heterogeneous human malignancies. The differential diagnosis of MPNST from other spindle cell neoplasms poses great challenges for pathologists. This report provides a mini-review of these unique features associated with MPNST.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

Journal of Cancer 2012, 3

http://www.jcancer.org

303

J Jo ou ur rn na al l o of f C Ca an nc ce er r

2012; 3: 303-309. doi: 10.7150/jca.4179

Mini-Review/Case Report

Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: Differentiation Patterns and

Immunohistochemical Features - A Mini-Review and Our New Findings

Aitao Guo, Aijun Liu

, Lixin Wei, Xin Song

Department of Pathology, the Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100853, China.

Corresponding author: Dr. Aijun Liu, Department of Pathology, the General Hospital of PLA, Beijing 100853, China.

Email:liuaj@301hospital.com.cn. Telephone: +86-10-66936253.

Ivyspring International Publisher. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License (http://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Reproduction is permitted for personal, noncommercial use, provided that the article is in whole, unmodified, and properly cited.

Received: 2012.02.01; Accepted: 2012.05.28; Published: 2012.07.04

Abstract

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) represent a group of highly heteroge-

neous human malignancies often with multiple histological origins, divergent differentiation

patterns, and diverse immunohistochemical presentations. The differential diagnosis of

MPNST from other spindle cell neoplasms poses great challenges for pathologists. This report

provides a mini-review of these unique features associated with MPNST and also presents the

first cases of MPNST with six differentiation patterns.

Key words: Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, Liposarcomatous; Glandular, Fibrohistio-

cytoid, Neuroendocrine differentiation, Cartilage, Triton tumor, Gangliocyte.

A. Differentiation Patterns

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

(MPNST), also known as Malignant schwannoma,

Neurofibrosarcoma, or Neurosarcoma, is derived

from Schwann cells or pluripotent cells of the neural

crest [1-5]. Epithelioid or other heterogeneous com-

ponents can be observed in 15% of MPNSTs [1, 2, 6]:

the latter include rhabdomyoblasts [1, 2, 6-12], carti-

laginous [6, 13, 14], osseous [6, 12, 13] differentiations

and, rarely, smooth muscle [13, 15], glandular [6,

10-12, 16] or liposarcomatous components [6, 12, 17]

have been reported. It is rare that there are two or

more heterogeneous components in a single MPNST.

To our best knowledge, MPNST with four differenti-

ated components has been described only in one case

[12]. Herein, we report one case of MPNST with six

differentiated components.

MPNSTs can be graded II, III or IV according to

WHO classification [1]. They account for only 5% of

malignant soft tissue tumors [1, 2, 7]. One half to two

thirds arises from neurofibromas, often of plexiform

neurofibromas or in the setting of neurofibromatosis

type I, which occur frequently on the head or neck.

The other MPNSTs arise de novo, which usually in-

volve the peripheral nerves in the buttocks or thighs,

mostly the sciatic nerve [1].

MPNST is generally characterized by alternating

hypo- and hyper-cell areas or a diffuse growth pattern

of spindle-shaped cells which are asymmetrical and

fusiform with wavy or comma-shaped hyperchro-

matic nuclei, arranged in palisades or spiral shapes

[1-3, 7, 8, 18, 19]. In about 15% of MPNSTs, epithelioid

or heterologous differentiation can be found [1]; the

later includes rhabdomyoblasts, smooth muscle, bone,

cartilage, and neuroendocrine component [1-24]. The

most common heterologous component in MPNST is

rhabdomyoblast differentiation [1, 7, 8], being first

reported by Masson in 1932 and named "nerve rhab-

domyoma", and later renamed by Woodruff as "ma-

lignant triton tumor". Additionally, differentiation

into cartilage or bone is also not uncommon [6, 12-14],

while liposarcomatous differentiation is very rare; to

date, only 4 cases have been reported [6, 12, 17].

Ivyspring

International Publisher

Journal of Cancer 2012, 3

http://www.jcancer.org

304

MPNST also has glandular structures [1, 2, 6, 10-12,

16], and foci of neuroendocrine differentiation are

often seen in glandular MPNST [1]. The combination

with more than two components is very rare; to our

best of known, only one MPNST case simultaneously

with epithelioid differentiation, rhabdomyosarcoma,

bone, and liposarcoma has been reported [12]. In the

present case, six kinds of differentiation, including

rhabdomyosarcomatous, chondral, glandular, neu-

roendocrine, gangliocytic, and liposarcomatous

components were observed in the background of a

classical MPNST. The histological changes are so

complex and diverse that no simple definition can

cover such a wide range of differentiation, and a final

diagnose of MPNST was made.

The diagnosis of MPNST with multiple mesen-

chymal differentiations is difficult, and sometimes

should be differentiated from rhabdomyosarcoma,

osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma or liposarcoma [6]. In

most cases, only regional or focal above-mentioned

differentiation can be observed on the background of

typical spindle-shaped tumor cells, which is easy to

identify. However, rhabdomyosarcomatous differen-

tiation occasionally becomes predominant; differen-

tial diagnosis is very difficult, especially in pediatric

patients; thus, the localization of the tumor and suffi-

cient sampls of the specimen are very important.

In 5-10% of dedifferentiated liposarcomas, my-

oblasts, cartilage, and osteosarcomatous differentia-

tion can be observed [6, 9]; however, the predomi-

nancy is composed of malignant fibrous histiocytoma

and/or leiomyosarcoma, and the ordinary MPNST

structure and epithelioid or glandular differentiations

should not be visible, and medical history and tumor

location are of keypoints for diagnosis. For example,

dedifferentiated liposarcoma tends to occur in deep

locations such as the retroperitoneal area, and some

patients may have surgical resection history of a typ-

ical liposarcoma [6, 9].

Additionally, MPNST with glandular differenti-

ation must be differentiated from metastatic carcino-

ma. In MPNST, the spindle-shaped cells around

glandular differentiation are also tumor cells, with

thin and red stained cytoplasm, and wavy or com-

ma-shaped hyperchromatic nuclei; however, in meta-

static carcinoma, spindle-shaped cells around the

glandular structures are often reactive proliferating

fibroblasts. Full physical examination is also helpful

for differential diagnosis.

MPNST is a tumor associated with an aggres-

sive behavior and its prognosis is poor with death

occurring in 63%, usually with 2-year of diagnosis.

The 2-year and 5-year overall survival rate are re-

ported to be 57% and 39% [8], with the median sur-

vival period is 32 months [3]. Surgical resection is the

best available option for treating MPNST [3, 7, 8, 23].

Relatively better prognosis can be seen in the patients

with a superficial and smaller tumor, complete exci-

sion and/or with family history [1-3, 20, 22, 29]. But

the prognosis is poorer in patients with rhabdomyo-

sarcomatous differentiation, the 2-year and 5-year

survival rates are 15% and 11% [8], respectively. And

the mortality rate is increased to 79% in tumors with

glandular differentiation [1]. In this case, MPNST re-

curred in the original location 10 months after resec-

tion, but chest CT and whole body bone scan did not

demonstrate metastases in the lungs or bones. The

patient is still under follow-up.

B. Immunohistochemical Features

Some neural markers, such as S-100, CD56 and

protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) are considered

sensitive markers for peripheral nerve sheath tumors.

S-100, which is traditionally regarded as the best

marker for MPNST, has limited diagnostic utility and

is positive in only about 50-90% of the tumors [8]. In

high grade MPNST, only scattered, if any, tumor cells

are S-100 positive [1, 23]. On the other hand, although

sensitive, CD56 and PGP 9.5 expression is in no way

specific for tumors of MPNST [24]. Thereby, MPNSTs

per se lack sufficiently specific and sensitive im-

munohistochemical marker. Recent studies suggest

that nestin, which is an intermediate filament protein,

is more sensitive for MPNST than other neural mark-

ers (S-100, CD56 and PGP 9.5) and immunostains for

nestin in combination with other markers could be

useful in the diagnosis of MPNST [25]. To cases with

divergent differentiation only typical tumor compo-

nents correspond to special immunophenotyping, as

indicated in the present case. The spindle and glan-

dular tumor cells were positive for S-100 and nestin,

and most spindle-shaped cells were positive for vi-

mentin. Cytokeratin was expressed in the glandular

region, CD56 expressed in most spindle-shaped cells

and rosette formations, and Syn in some rosette for-

mations. Actin was positive focally, and other myo-

genic markers were negative.

MPNST with glandular differentiations should

be distinguished from other tumors with dual differ-

entiation such as synovial sarcoma and mesothelioma.

Histological separation of MPNST from synovial sar-

comas can be difficult and available immunohisto-

chemical markers, such as S-100 and cytokeratin,

sometimes give rise to overlapping staining patterns.

Immunostaining EMA/CK7 for synovial sarcoma and

nestin/S100 for MPNST yielded high specificity and

positive predictive values [26]. Recent study consid-

ered that expression of HMGA2 is a feature of MPNST

Journal of Cancer 2012, 3

http://www.jcancer.org

305

but not of synovial sarcoma and immunohistochemi-

cal staining of HMGA2 may be a useful marker to

separate MPNST from synovial sarcoma [27]. Another

study showed the presence of SYT-SSX fusion tran-

script analyzed by real-time reverse transcription

polymerase chain reaction can be useful in the diag-

nosis of synovial sarcoma [28]. In MPNST goblet cells

and neuroendocrine differentiation are often seen in

glandular structures, which are seldom found in

mesothelioma. Immunohistostaining for Calretinin, in

combination with the tumor site, is also helpful to

differentiate mesothelioma from MPNST. The ex-

pression of Calretinin is uncommon in MPNST.

C. Our new findings

Clinical data

A 79-year-old man was hospitalized because of

an enlarging mass in his left thigh for 2 years. In-

traoperative findings showed that a solid subcutane-

ous mass, which protruded about one centimeter

above the skin surface, closely connected to the lateral

femoral nerve and slightly adherent to the vastus lat-

eralis muscle. The tumor mass was completely re-

sected with part of skin covering on it. Previous his-

tory of the patient was unremarkable except chole-

cystectomy due to cholecystitis and cholelithiasis 12

years ago.

Laboratory Tests

The surgical specimen was fixed in 10% neutral

formalin, routinely processed, paraffin embedded,

sectioned at 3 um thick, and stained conventionally

with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochem-

istry, four-micrometer sections of the paraf-

fin-embedded tissues were deparaffinized, rehydrat-

ed in a graded series of alcohol and micro-

wave-treated for 10 min in the citrate buffer (pH 6.0).

Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using

0.3% hydrogen peroxide. The tissue were processed in

an automatic IHC staining machine using the stand-

ard protocols (Lab Vision Autostainer, Lab Vision Co.,

Fremont, CA, USA) with DAKO Real EnVision

Detection System (K5007, DAKO). All antibodies were

bought from DAKO Co. The signals were visualized

with 3-3-diaminobenzidine and counterstained with

Mayer's hematoxylin. The antigens are summarized in

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical staining showed that the

spindle and grandular tumor components were posi-

tive for S-100 (Figure 4A and 4B). Cytokeratin was

expressed in the region of epithelioid differentiation

(Figure 5A). Most of the spindle cells were positive for

vimentin (Figure 5B) and some positive for CD56

(Figure 5C). Rosette formations areas expressed CD56

(Figure 5D), Syn (Figure 5E) and CD99. Actin was

positive focally, and other antibodies were all nega-

tive (Table 1).

Table 1 Immunohistochemical reagents and results.

Antibodies Clone No. Pretreatments and dilutions Expression in different components

SSC chondroid LS RMS E/G NE

S-100 multi-Clone HP 1:2000 + + + +

nestin GN-1401 HP 1:200 + - + +

vimentin Vim3B4 HP 1:100 + + + +

MBP 7H11 NPT 1:100 - - -

cytokeratin AE1/AE3 NPT 1:200 - + +

CD56 1B6 HP 1:150 + + +

CD99 12E7 HP 1:100 + + +

Syn multi-Clone HP 1:150 - - +

CgA 5H7 NPT 1:75 - - -

actin HHF35 HP 1:100 - + - -

desmin D33 NPT 1:100 - - -

MyoD1 5.8A GE 1:100 - - -

myoglobin MY018 GE 1:100 - - -

myosin F5D HP 1:200 - - -

SMA 1A4 HP 1:100 - - -

CD34 QBEnd10 HP 1:150 - - -

Bcl-2 124 HP 1:150 +/- + +

MBP myelin basic protein, HP high pressure, GE gastric enzyme, NPT non- pretreatments, SSC spindle shaped cell, LS liposarcomatous,

RMS rhabodomyosarcomatous, E/G epithelioid/glandular, NE neuroendocrine, component was not stained with any antibody.

Journal of Cancer 2012, 3

http://www.jcancer.org

306

Figure 1. The tumor is located in the dermis without encapsulated (HE X 40).

Figure 2. In most regions, tumor cells are arranged in bundles with red-stained and scant cytoplasm, and spindle-shaped nuclei (2A);

tumor cells grew in storiform as that in fibrous histiocytoma (2B); glandular differentiation (2C) and neuroendcrime differentiation (2D)

(HE X 100).

Journal of Cancer 2012, 3

http://www.jcancer.org

307

Figure 3. In some regions of the tumor, the differentiation of cartilage (3A), rhabdomyosarcoma (3B), liposarcoma (3C), and ganglion

cells (arrow) (3D) can be seen (HE X 100).

Figure 4. Immunohistochemical staining for S-100 was positive in most spindle shaped (4A) (X 100) and glandular (4B) (X 100) tumor

cells.

Journal of Cancer 2012, 3

http://www.jcancer.org

308

Figure 5. Immunohistochemical staining for Cytokeratin was positive in most epithelioid tumor cells and negative in the fusiform region

(5 A) (X 100). Vimentin was positive in the majority of spindle -shaped cells, and negative in the epithelioid region (5 B) (X 100). CD56

was positive in tumor tissue with spindle-shaped cells (5C) and neuroendocrine differentiation (5D) (X 100). Synaptophysin was positive

in some neuroendocrine diffentiated tumor cells (5E) (X 100).

Pathologic findings

By gross examination, the fusiform mass was

9cm 6cm 5cm in size and the covering skin is 8cm

x 6cm in size. The cut surface revealed two inde-

pendent nodules of 5cm 4.5cm 3.5cm and 4cm

2cm 1.5cm in size, respectively. Both of them were

soft in texture, pale-gray and yellowish in colour, and

well demarcated without encapsulation.

Microscopically, the tumor was well circum-

scribed without encapsulation and invaded the der-

mis and subcutis tissues (Figure 1). The tumor was

mainly composed of spindle-shaped cells with thin

and eosinophilic cytoplasms and atypical nuclei. The

tumor cells arranged in bundles and wave pattern in

most areas (Figure 2A), and in some areas, arranged

radially or in whorls with abundant spoke-like struc-

tures (Figure 2B). Myxoid degeneration was visible in

some parts of the tumor. Epithelioid differentiation

with glandular structures (Figure 2C) appeared in

multiple foci, and rosette formation, indicating neu-

roendocrine differentiation, were also observed (Fig-

ure 2D) in these areas. Distinct chondro-

differentiation could be seen focally (Figure 3A). In

some fields the tumor cells showed eosinophilic cy-

toplasms with eccentric nuclei, resembling rhabdo-

myoblasts (Figure 3B), and in the other areas typical

lipoblasts were also visible (Figure 3C). Ganglion cells

were focally scattered (Figure 3D). Multiple patches of

necrosis were observed. Pathological diagnosis was

MPNST with heterougenous differentiations, WHO

grade IV.

Follow-up

The patient was postoperatively treated with

radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and 3 months later

he received traditional Chinese medicine treatment

for 15 days. The tumor recurred in the original site 10

months after tumor resection. Imaging examination

demonstrated muscular invasion; however, chest CT

and whole body bone scan did not reveal any metas-

tasis.

Journal of Cancer 2012, 3

http://www.jcancer.org

309

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing

interest exists.

References

1. Danid NL, Hiroko O, Otmar DW, et al. WHO classification of tu-

morspathology and genetics of tumors of the nervous system; 4th

Edition. WHO. 2007:160.

2. Rodriguez FJ, Folpe AL, Giannini C, Perry A. Pathology of peripheral

nerve sheath tumors: diagnostic overview and update on selected diag-

nostic problems. Acta Neuropathol. 2012; 123: 295-319.

3. Kar M, Deo SV, Shukla NK, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath

tumors (MPNST)--clinicopathological study and treatment outcome of

twenty-four cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2006; 22: 55-63.

4. Yamaguchi U, Hasegawa T, Hirose T, et al. Low grade malignant pe-

ripheral nerve sheath tumour: varied cytological and histological pat-

terns. J Clin Pathol 2003; 56: 826830.

5. Rekhi B, Abhijeet I, Rajiv K, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath

tumors: Clinicopathological profile of 63 cases diagnosed at a tertiary

cancer referral center in Mumbai, India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;

53: 611-618.

6. Roberto T, Malcolm G, Robert B, et al. Liposarcomatous differentiation in

malignant peripheral nerve shenath tumor:a case report. Pathol Res

Practice, 2010; 206: 138-142.

7. Rekhi B, Jambhekar NA, Puri A, et al. Clinicomorphologic features of a

series of 10 cases of malignant triton tumors diagnosed over 10 years at a

tertiary cancer hospital in Mumbai, India. Annals of Diagnostic Pathol-

ogy 2008;12: 9097.

8. Stasik CJ, Tawfik O. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor With

Rhabdomyosarcomatous Differentiation (Malignant Triton Tumor).

Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:18781881.

9. Peter P, Jerome B, Thomas K, et al. Divergent differentiation in malig-

nant soft tissue neoplasms: the paradigm of liposarcoma and malignant

peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Int J Surg Pathol, 2005;13:19-28.

10. Tetsuro Nagasaka, Raymond Lai, Michihiko Sone, et al. Glandular

Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor An Unusual Case Showing

Histologically Malignant Glands. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

2000;124:13641368.

11. Li H, Carmen E, Ronald W, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath

tumor with divergent differentiation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003; 127:

e147- e150.

12. Suresh TN, Harendra Kumar ML, Prasad CSBR, et al. Malignant pe-

ripheral nerve sheath tumor with divergent differentiation. Indian J

Patho Microbiology, 2009;52:74-76

13. Janczar K, Tybor K, Jzefowicz M, et al. Low grade malignant peripheral

nerve sheath tumor with mesenchymal differentiation: a case report. Pol

J Pathol. 2011;62:278-281.

14. Tetsuji Yamamoto, Rieko Minami, Chiho Ohbayashi. Subcutaneous

malignant epithelioid schwannoma with cartilaginous differentiation. J

Cutan Pathol 2001; 28: 486491.

15. Rodriguez FJ, Scheithauer BW, Abell-Aleff PC, et al. Low grade malig-

nant peripheral nerve sheath tumor with smooth muscle differentiation.

Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:705-709.

16. Woodruff JM, Christensen WN. Glandular peripheral nerve sheath

tumors. Cancer 1993; 72: 3618-3628.

17. Samruay S, Sunpetch B, Soottiporn C. Malignant mesenchymoma of

median nerve: combined nerve shenath sarcoma and liposarcoma. J surg

oncol, 1984;25:119-123.

18. A Takeuchi & S Ushigome1. Diverse differentiation in malignant pe-

ripheral nerve sheath tumours associated with neurofibromatosis-1: an

immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Histopathology. 2001;

39:298-309.

19. Allison KH, Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Rubin BP. Superficial Malignant

Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:685-692.

20. Zhu B, Liu XG, Liu ZJ, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours

of the spine: clinical manifestations, classification, treatment, and prog-

nostic factors. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:897-904.

21. Ducatman BS, Scheithauer BW. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath

tumors with divergent differentiation. Cancer. 1984; 54:1049-1057.

22. Cashen DV, Parisien RC, Raskin K, et al. Survival data for patients with

malignant schwannoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;426:69-73.

23. Ramanathan RC, Thomas J. M Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tu-

mours associated with von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis. Eur J

Surg Oncol. 1999;25:190-193.

24. Campbell LK, Thomas JR, Lamps LW, et al. Protein gene product 9.5

(PGP 9.5) is not a specific marker of neural and nerve sheath tumors: an

immunohistochemical study of 95 mesenchymal neoplasms. Mod

Pathol. 2003;16: 963-969.

25. Shimada S, Tsuzuki T, Kuroda M, et al. Nestin expression as a new

marker in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Pathol Int. 2007;

57: 60-67.

26. Olsen SH, Thomas DG, Lucas DR. Cluster analysis of immunohisto-

chemical profiles in synovial sarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve

sheath tumor, and Ewing sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2006; 19: 659-668.

27. Hui P, Li N, Johnson C, et al. HMGA proteins in malignant peripheral

nerve sheath tumor and synovial sarcoma: preferential expression of

HMGA2 in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Mod Pathol. 2005;

18: 1519-1526.

28. Miettinen M. From morphological to molecular diagnosis of soft tissue

tumors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006; 587: 99-113.

29. Ducatman BS, Scheithauer BW, Piepgras DG, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A clinicopathologic study of

120 cases. Cancer. 1986;57:2006-2021.

You might also like

- Round Cell Tumors - Classification and ImmunohistochemistryDocument13 pagesRound Cell Tumors - Classification and ImmunohistochemistryRuth SalazarNo ratings yet

- Small Round Cells of Head and NeckDocument10 pagesSmall Round Cells of Head and NeckBlazxy EyreNo ratings yet

- Malignant Small Round Cell TumorsDocument12 pagesMalignant Small Round Cell TumorsSaptarshi Ghosh100% (1)

- Review Article: Osteosarcoma: Cells-of-Origin, Cancer Stem Cells, and Targeted TherapiesDocument14 pagesReview Article: Osteosarcoma: Cells-of-Origin, Cancer Stem Cells, and Targeted TherapiesJavier Ernesto GuavaNo ratings yet

- Spindle Cell LesionsDocument8 pagesSpindle Cell LesionsdrmanishsharmaNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissues PathologyDocument53 pagesSoft Tissues PathologyWz bel DfNo ratings yet

- MPNST Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument27 pagesMPNST Diagnosis and TreatmentrahadiyantiNo ratings yet

- Small Round Cell TumorsDocument131 pagesSmall Round Cell TumorschinnnababuNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcomas: A Review of Rhabdomyosarcomas and Nonrhabdomyosarcoma SarcomasDocument9 pagesPediatric Soft Tissue Sarcomas: A Review of Rhabdomyosarcomas and Nonrhabdomyosarcoma SarcomasIndri WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Neuroendocrine Tumors: Surgical Evaluation and ManagementFrom EverandNeuroendocrine Tumors: Surgical Evaluation and ManagementJordan M. CloydNo ratings yet

- Practice Essentials: Timothy P Cripe, MD, PHD, Faap Chief, Division of Hematology/Oncology/BmtDocument30 pagesPractice Essentials: Timothy P Cripe, MD, PHD, Faap Chief, Division of Hematology/Oncology/BmtnamakuadalahnoeNo ratings yet

- Interactive Microscopy Session:: Second Edition: Modern Surgical Pathology Through The Expert Eyes of Apss-UscapDocument10 pagesInteractive Microscopy Session:: Second Edition: Modern Surgical Pathology Through The Expert Eyes of Apss-UscapalfonsoNo ratings yet

- Davanzo Solitary Fibrous Tumor 2018Document9 pagesDavanzo Solitary Fibrous Tumor 2018JZNo ratings yet

- NeuroblastomaDocument19 pagesNeuroblastomaTri Andhika Dessy WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Retro Peritoneal TumorDocument37 pagesRetro Peritoneal TumorHafizur RashidNo ratings yet

- Glandula SalialDocument45 pagesGlandula SalialJose Daniel Garcia AlatorreNo ratings yet

- Olfactory Neuroblastoma UP TO DATEDocument22 pagesOlfactory Neuroblastoma UP TO DATEZuleibis Melean LopezNo ratings yet

- Rare Tumour - Sebaceous Carcinoma of The ScalpDocument2 pagesRare Tumour - Sebaceous Carcinoma of The ScalpInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Correct ThesisDocument129 pagesCorrect ThesisANo ratings yet

- Ew WikiDocument8 pagesEw WikidesyonkNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and pathology of intraventricular tumorsDocument14 pagesEpidemiology and pathology of intraventricular tumorsNaim CalilNo ratings yet

- SCLC LancetDocument15 pagesSCLC LancetLeeTomNo ratings yet

- Brain TumorDocument15 pagesBrain TumorA Farid WajdyNo ratings yet

- Klasifikasi MeningiomaDocument8 pagesKlasifikasi Meningiomahusna fitriaNo ratings yet

- Uji PKDocument3 pagesUji PKRosmazila MohamadNo ratings yet

- Common Musculoskeletal Tumors of ChildhoodDocument13 pagesCommon Musculoskeletal Tumors of ChildhoodMari CherNo ratings yet

- Fibrosarcoma: Continuing Education ActivityDocument5 pagesFibrosarcoma: Continuing Education ActivityDiana Tarisa Putri0% (1)

- Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor With Rhabdomyosarcomatous Differentiation (Malignant Triton Tumor)Document4 pagesMalignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor With Rhabdomyosarcomatous Differentiation (Malignant Triton Tumor)NIck MenzelNo ratings yet

- Ijms 19 00311Document26 pagesIjms 19 00311Hidayat ArifinNo ratings yet

- Angiosacaaroma 1Document15 pagesAngiosacaaroma 1Francisco ZurgaNo ratings yet

- Systemic Therapy For Selected Skull Base Sarcomas Cho 2016 Reports of PractDocument9 pagesSystemic Therapy For Selected Skull Base Sarcomas Cho 2016 Reports of PractOana VarvariNo ratings yet

- Articulo 1Document17 pagesArticulo 1Andrea NeriaNo ratings yet

- Lcnec Versus SCLCDocument76 pagesLcnec Versus SCLCnurul hidayahNo ratings yet

- Practice Essentials: View Media GalleryDocument8 pagesPractice Essentials: View Media GallerywzlNo ratings yet

- Flash Points in Special Pathology[Compiled] by Medical Study CenterDocument55 pagesFlash Points in Special Pathology[Compiled] by Medical Study Centerhhewadamiri143No ratings yet

- Neuroblastoma Cerebral: Diagnóstico y Tratamiento: R. Prat, I. Galeano, F.J. Conde, P. Febles, S. CortésDocument3 pagesNeuroblastoma Cerebral: Diagnóstico y Tratamiento: R. Prat, I. Galeano, F.J. Conde, P. Febles, S. CortésjoaquinNo ratings yet

- Rare Bone Tumor: Chondromyxoid FibromaDocument8 pagesRare Bone Tumor: Chondromyxoid FibromaputriNo ratings yet

- Oncovet 2008Document18 pagesOncovet 2008Frederico VelascoNo ratings yet

- Metastasic CancerDocument6 pagesMetastasic CancerMartha ElenaNo ratings yet

- Primary Chest Wall TumorsDocument13 pagesPrimary Chest Wall Tumorsmhany12345No ratings yet

- MedulloblastomaDocument6 pagesMedulloblastomaMohammadAwitNo ratings yet

- Editorial: Metastatic Neoplasms To The Intraocular StructuresDocument3 pagesEditorial: Metastatic Neoplasms To The Intraocular StructuresDeniz MJNo ratings yet

- Astrocytoma 10.1007/s00401-015-1410-7Document14 pagesAstrocytoma 10.1007/s00401-015-1410-7Rikizu HobbiesNo ratings yet

- Meningioma BrochureDocument16 pagesMeningioma BrochureAyu Rahmi AMyNo ratings yet

- D M P S: Ecision Aking and Roblem OlvingDocument6 pagesD M P S: Ecision Aking and Roblem OlvingMaya RustamNo ratings yet

- Common Malignant Salivary Gland Epithelial TumorsDocument39 pagesCommon Malignant Salivary Gland Epithelial TumorsJesús De Santos AlbaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Sarcomas of Bone - Clinical GateDocument8 pagesPediatric Sarcomas of Bone - Clinical GateAkira MasumiNo ratings yet

- Round Cell Tumors FinalDocument86 pagesRound Cell Tumors FinalKush Pathak100% (2)

- Orbital Rhabdomyosarcomas ReviewDocument9 pagesOrbital Rhabdomyosarcomas ReviewHermawan LimNo ratings yet

- WHO classification of soft tissue tumours guideDocument10 pagesWHO classification of soft tissue tumours guidezakibonnie100% (1)

- Treatment Options For Medulloblastoma and CNS Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (PNET)Document14 pagesTreatment Options For Medulloblastoma and CNS Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (PNET)Utami DewiNo ratings yet

- 2011-01 Goldblum Common Morphologic PatternsDocument35 pages2011-01 Goldblum Common Morphologic PatternsDrRobin SabharwalNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 278458Document8 pagesNi Hms 278458VidinikusumaNo ratings yet

- Leptomeningeal DiseaseDocument17 pagesLeptomeningeal DiseaseForem ZayneNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis, Classification, and Management of Soft Tissue SarcomasDocument17 pagesDiagnosis, Classification, and Management of Soft Tissue SarcomasSafrilia GandhiNo ratings yet

- Mucin1 Expression in Relation To Histomorphological Type of Colorectal Carcinoma: A Cross Sectional StudyDocument6 pagesMucin1 Expression in Relation To Histomorphological Type of Colorectal Carcinoma: A Cross Sectional StudyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Tumors of The Nervous SystemDocument45 pagesTumors of The Nervous SystemIsaac MwangiNo ratings yet

- Uterine Smooth Muscle TumorsDocument22 pagesUterine Smooth Muscle TumorsVuk MilutinovićNo ratings yet

- Multiple Myeloma ESMO Clinical Practice GuidelinesDocument5 pagesMultiple Myeloma ESMO Clinical Practice GuidelinesFlaKitaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Neuro-Oncology: Understanding Brain Tumors in ChildrenDocument17 pagesPediatric Neuro-Oncology: Understanding Brain Tumors in ChildrenRandy UlloaNo ratings yet

- Gallstone Disease and The Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational StudiesDocument7 pagesGallstone Disease and The Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational StudiesAfkar30No ratings yet

- Abstrak Jonata (English)Document1 pageAbstrak Jonata (English)Afkar30No ratings yet

- Outcomes of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument9 pagesOutcomes of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisAfkar30No ratings yet

- Spence 2017Document5 pagesSpence 2017Afkar30No ratings yet

- Appendicial MassDocument15 pagesAppendicial MassAfkar30No ratings yet

- DR Kiki Lukman Patofisiologi Acute CholangitisDocument36 pagesDR Kiki Lukman Patofisiologi Acute CholangitisAfkar30No ratings yet

- Dok Baru 2021-06-07 08.38.01 - 2Document1 pageDok Baru 2021-06-07 08.38.01 - 2Afkar30No ratings yet

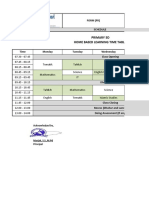

- Primary 5D Home Based Learning Time Table: Form (FR)Document3 pagesPrimary 5D Home Based Learning Time Table: Form (FR)Afkar30No ratings yet

- Dok Baru 2021-06-07 08.38.01 - 1Document1 pageDok Baru 2021-06-07 08.38.01 - 1Afkar30No ratings yet

- Prospective Clinical Study: Mass Closure Versus Layer Closure of Abdominal WallDocument6 pagesProspective Clinical Study: Mass Closure Versus Layer Closure of Abdominal WallAfkar30No ratings yet

- FS PustakaDocument4 pagesFS PustakaAfkar30No ratings yet

- Appendicial MassDocument2 pagesAppendicial MassAfkar30No ratings yet

- Dok Baru 2021-06-07 08.38.01Document3 pagesDok Baru 2021-06-07 08.38.01Afkar30No ratings yet

- Original Research Paper: GastroenterologyDocument3 pagesOriginal Research Paper: GastroenterologyAfkar30No ratings yet

- Guidelines For Surgery in The HIV Patient: Samuel Smit, MB CHB, M Med (Surg)Document8 pagesGuidelines For Surgery in The HIV Patient: Samuel Smit, MB CHB, M Med (Surg)Afkar30No ratings yet

- 03 Chemo PrincDocument17 pages03 Chemo PrincMareeze HattaNo ratings yet

- Abstrak Jonata (English)Document1 pageAbstrak Jonata (English)Afkar30No ratings yet

- Imaging Correlation of The Degree of Degenerative L4-5 Spondylolisthesis With The Corresponding Amount of Facet FluidDocument6 pagesImaging Correlation of The Degree of Degenerative L4-5 Spondylolisthesis With The Corresponding Amount of Facet FluidAfkar30No ratings yet

- Abstrak Dr. Deny SafitriDocument2 pagesAbstrak Dr. Deny SafitriAfkar30No ratings yet

- Salah Satu Syarat Guna Memperoleh Gelar Dokter Spesialis BedahDocument1 pageSalah Satu Syarat Guna Memperoleh Gelar Dokter Spesialis BedahAfkar30No ratings yet

- Appendicial MassDocument2 pagesAppendicial MassAfkar30No ratings yet

- Dr. Wifanto-Management Liver Metastasis CRCDocument46 pagesDr. Wifanto-Management Liver Metastasis CRCAfkar30No ratings yet

- Basic Surgical Skills Course PalembangDocument2 pagesBasic Surgical Skills Course PalembangAfkar30No ratings yet

- Abstrak Jonata (English)Document1 pageAbstrak Jonata (English)Afkar30No ratings yet

- Blunt Abdominal Trauma PDFDocument6 pagesBlunt Abdominal Trauma PDFrizkaNo ratings yet

- POster Mba Alicia JugaDocument23 pagesPOster Mba Alicia JugaAfkar30No ratings yet

- Esofageal Stenosis - DR AnungDocument26 pagesEsofageal Stenosis - DR AnungAfkar30No ratings yet

- Trauma Buli Dan UrethraDocument6 pagesTrauma Buli Dan UrethraAfkar30No ratings yet

- KoreksiDocument6 pagesKoreksiAfkar30No ratings yet

- Abses Hepar 2014Document2 pagesAbses Hepar 2014Afkar30No ratings yet

- Bmjopen 2017 016402Document6 pagesBmjopen 2017 016402Ćatke TkećaNo ratings yet

- Digestive System PowerpointDocument33 pagesDigestive System PowerpointThomas41767% (6)

- Safety Reports Series No. 13 (Radiation Protection and Safety in Industrial Radiography)Document69 pagesSafety Reports Series No. 13 (Radiation Protection and Safety in Industrial Radiography)jalsadidiNo ratings yet

- Breakfast of ChampionsDocument34 pagesBreakfast of ChampionsTamanna TabassumNo ratings yet

- NUST Hostel Admission Form New PDFDocument2 pagesNUST Hostel Admission Form New PDFMuhammad Waqas0% (1)

- Undulating Periodization For BodybuildingDocument24 pagesUndulating Periodization For BodybuildingPete Puza89% (9)

- DSM 5Document35 pagesDSM 5Hemant KumarNo ratings yet

- Informed Consent and Release, Waiver, and Quitclaim: Know All Men by These PresentsDocument2 pagesInformed Consent and Release, Waiver, and Quitclaim: Know All Men by These PresentsRobee Camille Desabelle-SumatraNo ratings yet

- Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic in The Philippines PDFDocument13 pagesPsychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic in The Philippines PDFAndrea KamilleNo ratings yet

- Pricelist Aleena Skin Clinic KendariDocument2 pagesPricelist Aleena Skin Clinic Kendariwildan acalipha wilkensiaNo ratings yet

- Endocrine DisruptorsDocument50 pagesEndocrine DisruptorsSnowangeleyes AngelNo ratings yet

- Understanding Uterine FibroidsDocument52 pagesUnderstanding Uterine FibroidsDoctor JitNo ratings yet

- 31congenital GlaucomasDocument12 pages31congenital GlaucomasShari' Si WahyuNo ratings yet

- Topical Agents and Dressings For Local Burn Wound CareDocument25 pagesTopical Agents and Dressings For Local Burn Wound CareViresh Upase Roll No 130. / 8th termNo ratings yet

- Family Nursing Care PlanDocument1 pageFamily Nursing Care PlanDersly LaneNo ratings yet

- Assessed Conference Presentations ScheduleDocument2 pagesAssessed Conference Presentations ScheduleAna Maria Uribe AguirreNo ratings yet

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Question PapersDocument22 pagesObstetrics and Gynecology Question Papersprinceej83% (18)

- Being A Medical DoctorDocument14 pagesBeing A Medical DoctorMichael Bill GihonNo ratings yet

- Pta ResumeDocument2 pagesPta Resumeapi-669470996No ratings yet

- Laboratory Hygiene and SafetyDocument34 pagesLaboratory Hygiene and SafetyResmiNo ratings yet

- Journal On The Impact of Nursing Informatics To Clinical PracticeDocument2 pagesJournal On The Impact of Nursing Informatics To Clinical PracticeLhara Vhaneza CuetoNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment For Balustrade Glass InstallationDocument3 pagesRisk Assessment For Balustrade Glass InstallationNicos PapadopoulosNo ratings yet

- Yoga Your Home Practice CompanionDocument257 pagesYoga Your Home Practice Companionjohncoltrane97% (33)

- GastroparesisDocument10 pagesGastroparesisapi-437831510No ratings yet

- Emotional Dysregulation in Adult ADHD What Is The Empirical EvidenceDocument12 pagesEmotional Dysregulation in Adult ADHD What Is The Empirical EvidenceVo PeaceNo ratings yet

- Care of A Child With Cardiovascular DysfunctionDocument71 pagesCare of A Child With Cardiovascular DysfunctionMorgan Mitchell100% (1)

- IFUk en 310250 07 PDFDocument14 pagesIFUk en 310250 07 PDFKhaled AlkhawaldehNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire/interview Guide Experiences of Checkpoint Volunteers During The Covid-19 PandemicDocument16 pagesQuestionnaire/interview Guide Experiences of Checkpoint Volunteers During The Covid-19 PandemicKrisna Criselda SimbreNo ratings yet

- Thesis-Android-Based Health-Care Management System: July 2016Document66 pagesThesis-Android-Based Health-Care Management System: July 2016Noor Md GolamNo ratings yet

- Brett Stolberg 100112479 - ResumeDocument1 pageBrett Stolberg 100112479 - Resumeapi-193834982No ratings yet

![Flash Points in Special Pathology[Compiled] by Medical Study Center](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/724273041/149x198/ab8ed569e7/1713441931?v=1)