Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reflection Paper Example6

Uploaded by

Xiao HoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reflection Paper Example6

Uploaded by

Xiao HoCopyright:

Available Formats

Reflecting on Advanced Skills and Standards Workshop

Advanced Skills and Standards (ASAS) was an exciting and fast paced workshop. The

lessons taught at ASAS covered introductory exercises, warm ups, games, low and high

challenge course operating procedures, and thorough technical training on knots, equipment,

construction, rescue procedures and risk management aspects of challenge course operation.

Demonstration performance and small group problem solving were the primary means of

teaching the technical portions of the workshop. The skills learned in the ASAS workshop are

vital for maintaining safety on a challenge course. The ability to employ those skills when and

where needed, provide course operators the ability to instill the high level of trust required for

our participants to overcome the personal trepidation associated with challenge initiatives. The

belay and rescue portions of the ASAS workshop were particularly instrumental to my personal

ASAS experience.

Belaying Skills

Beyond the primary knowledge of common hardware and knots used on a challenge

course comes the primary means of maintaining climber safety for high initiatives, belaying. I

had learned belay techniques in a previous Technical Skills course. However, several of the

techniques were foreign to me at the time. Upon attending the Technical Skills course, my only

previous experience was on the job training at [my schools] Adventure Based Learning (ABL)

course. The ABL course, which I now operate, primarily uses what would best be described as a

Nut Eye Bolt version of a J ust-Rite Descender in which the Nut Eye Bolts are staggered in the

belay bench and are the belay system for all but one of my high events. When the different belay

techniques were incorporated into various scenarios at ASAS, I began to really understand the

situational uses for all of the techniques. For instance, a 1 person belay would be used for a

competent belayer in a situation such as course maintenance or in a rescue scenario where the

only other people available have limited belaying skills. The 2 person belay adds a measure of

safety. The back-up belayer is a second set of eyes on the climber, can keep the rope out of the

way, and can be used to build belay competency for the primary belayer. The 2 person belay is

also useful for traversing belays. The back-up belayer can manage the rope, keeping it clean and

out of the way, and allows the primary belayer to keep his/her full attention on the climber. A

third person can be added as an anchor for the primary belayer to keep the primary belayer from

being lifted off the ground in a situation where the climber is heavier than the belayer.

Australian and other forms of team belays are great belays for groups, taught easily, require a

minimum of equipment, and incorporate trust, communication, and teamwork. The next

challenges posed were situations requiring a person to remove himself from a belay.

Belay Escapes

Belay escapes were completely new to me prior to the ASAS workshop. The first rule

of a belay escape was to keep it simple. There were a handful of experienced climbers and

challenge course operators in my group and keeping it simple was initially hard to follow. One

of the great learning points was not to overlook the obvious. I believe that our desire to use our

technical skills to save the day often leads us to over-complication. In the first few challenges

posed to the group, the tendency was to overlook the obvious for more lengthy and complex

solutions. Surveying the situation and thinking the solution process through before acting was

the key to avoiding over-complication.

My personal experience with belay escapes since the ASAS workshop have all been

centered on course maintenance. More than once I have found myself at height and in need of a

tool or hardware. The best solutions have been for either the belayer or climber to tie off (escape

the belay) in order for someone on the ground to retrieve the needed equipment. This also

happened to me during the ASAS workshop. I was on belay and some members of my group

needed my assistance for a moment. I was able to tie off a sheriff by running the brake side of

the rope through the locking carabiner and tie it off back to the climbers side of the sheriff with

a backed up half hitch, and attach a releasable load prusik to an anchor in a very short amount of

time. Now thats experiential learning! As a result of my training, my facilitators and I always

carry extra carabiners and slings in order to be prepared for belay escape and rescue scenarios.

Rescues

The rescue portion of the workshop was a great experience full of important information

and challenges that may arise during high ropes events. The overarching themes were, to remain

calm, to think the entire process through, and to keep the process simple. The most common

experiences group participants and staff shared were instances that involved jammed clothing or

hair in belay devices. Two preventative measures to avoid these types of jams from occurring

are (1) to brief participants to secure loose clothing and hair before entering the challenge course

and (2) to employ some type of device, a sling/cordalette/or SAFER lanyard positioning ring to

move the belay device away from the body to help avoid objects from being entangled. When

items do get caught in belay devices, performing a rescue may be the next step.

While learning and performing the various rescue procedures I encountered 3 particular

learning moments. The first 2 were during my self-lower cut away rescue. While preparing to

perform my first rescue, I inspected the rescue bag and noticed that the steel carabiner that

connected my rescue figure eight to the belay line was a very old, perfectly symmetrical, screw

gate, oval carabiner. All of the steel carabiners in the rescue bags at my facility are 2 stage auto-

locking HMS type. Having noticed the difference, I deliberately positioned that particular

carabiner so that when I clipped into the belay cable, it would be oriented with the gate opening

down, allowing me to screw the gate closed in the down position after connecting it. Somewhere

in the belay transfer process the steel oval carabiner had flipped over, changing the orientation to

the gate opening in the up position. Under the stress of a rescue I failed to notice the carabiner

had flipped and I reached up and screwed the gate down, thinking I was securing it in the locked

position when in fact, I was unlocking the gate. I had failed to perform a gate check before

proceeding onto the cable. A ground observer caught the mistake right away and it was fortunate

the incident happened on the practice course. While it was not life threatening, the experience

left a strong impression.

The second challenge on the same rescue occurred as I was lowering my self to the

rescue victim. The rescue scissors lanyard was attached to my side gear loop with a non-locking

carabiner. As I was approaching the rescue victim, my body twisted from the twist in the rope

and the rescue scissors carabiner clipped itself to the rescue victims rope. The incident only

slowed me down for a short period, but it did create an unwanted distraction. Two of Project

Adventures senior staff members were on site at the time and agreed that they had never seen

and an accidental clip in happen in the past. This incident was another great lesson to have had

on the practice course. The final lesson during the rescue portion of ASAS was not one learned,

but one I taught.

As I observed the instructor demonstrate a 3 person zip-line rescue, I realized that a 3

person, 2 rope zip-line rescue may unnecessary. The rescuers belay line could be utilized for

getting the rescuer to the victim and the rescue lower, negating the need to involve another rope

and belay system. With some reservation, the instructor agreed to try out my idea and it worked.

The reason the suggestion worked is because there is a great deal more friction in the rescue

figure 8 than in the zip-line pulley. The instructor had reservations about the viability of the new

technique due to the potential inability for the rescuer to be lifted if he were inadvertently

lowered below the victims level. I performed 4 tests of my new zip-line rescue system at my

[schools] course. We performed 2 lowers using a pulley on the zip-wire and 2 tests using a steel

carabiner on the zip-wire. Two of the results using the steel carabiner without the cable pulley,

showed minimal lowering of the rescuer, 6 and 8 respectively. Any unwanted lowering of the

rescuer was overcome by the rescuer holding onto the break side of the rescue line while

traversing out to the victim. On the second attempt, the rescuer held the belay side of the rescue

rope with one hand; and found that one hand was sufficient to avoid unwanted creep in the

rescue line. The rescue portion of the ASAS workshop was particularly productive for me.

Conclusion

Attending the ASAS workshop has improved my ability to provide a safe and

meaningful experience to my customers. According to Project Adventures Advanced Skills

and Standards Workshop Manual, The ASAS workshop design provides learning at two

levels, one as a participant and the other as a teacher/facilitator of an Adventure program

(Project Adventure, 2005). Being a participant in the ASAS workshop has helped me to

empathize with my challenge course participants, and understand the processes that groups

experience as they attend my home course. As a facilitator, the knowledge and confidence

I gained from this training is reflected in my facilitation skills and technical knowledge. With

that knowledge, participants are free to expand their personal height and trust envelope.

After attending Project Adventures Advanced Skills and Standards workshop, I know that I

can handle an emergency situation in a safe and efficient manner and that I have the skills

necessary to operate and maintain a first-class challenge course.

References

Project Adventure, Inc. (2005). Advanced Skills and Standards: Workshop Manual.

Beverly, MA.

You might also like

- Learn Spanish, Chinese and English greetingsDocument11 pagesLearn Spanish, Chinese and English greetingsXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Albright DADM 5e - PPT - CH 10Document51 pagesAlbright DADM 5e - PPT - CH 10Xiao HoNo ratings yet

- Using Films to Engage Students in Learning About Social ProblemsDocument6 pagesUsing Films to Engage Students in Learning About Social ProblemsXiao HoNo ratings yet

- IIRP Reflection Tip SheetDocument2 pagesIIRP Reflection Tip SheetXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Quiz 1 0506b Key 1 For BlackboardDocument1 pageQuiz 1 0506b Key 1 For BlackboardXiao HoNo ratings yet

- W13 Property Tax Comp 2015Document4 pagesW13 Property Tax Comp 2015Xiao HoNo ratings yet

- Secretary Treasurer DutiesDocument2 pagesSecretary Treasurer DutiesXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Final Business EthicsDocument28 pagesFinal Business EthicsXiao HoNo ratings yet

- BBAIM 4-Year Structure For The 2013-14 Intake - Revised On 14jul2014 - Pending For Approval - For O'DayDocument1 pageBBAIM 4-Year Structure For The 2013-14 Intake - Revised On 14jul2014 - Pending For Approval - For O'DayXiao HoNo ratings yet

- US Deloittereview Sustainability 2.0 Jan12Document11 pagesUS Deloittereview Sustainability 2.0 Jan12Xiao HoNo ratings yet

- AdvantageDocument1 pageAdvantageXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Final Business EthicsDocument28 pagesFinal Business EthicsXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Hanzi WritingDocument7 pagesHanzi WritingXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Topic 2 CheatsheetDocument2 pagesTopic 2 CheatsheetXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Transportation and Assignment Problems Transportation ProblemDocument2 pagesTransportation and Assignment Problems Transportation ProblemXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Bi ConceptsDocument28 pagesBi ConceptsLauro EncisoNo ratings yet

- Topic 2 CheatsheetDocument2 pagesTopic 2 CheatsheetXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 CheatsheetDocument2 pagesTopic 1 CheatsheetXiao HoNo ratings yet

- IM MC Week 6Document5 pagesIM MC Week 6Xiao HoNo ratings yet

- CTL 2956 HYK - Chinese Finals Pronunciation GuideDocument13 pagesCTL 2956 HYK - Chinese Finals Pronunciation GuideXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Tone Practice 1 Written MaterialDocument1 pageTone Practice 1 Written MaterialXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Phonics InitialsDocument9 pagesPhonics InitialsXiao HoNo ratings yet

- 4 Tones of Mandarin Chinese - Learn the Tones and Pitches of PutonghuaDocument1 page4 Tones of Mandarin Chinese - Learn the Tones and Pitches of PutonghuaXiao HoNo ratings yet

- MC Test on Value Chain and Competitive StrategyDocument5 pagesMC Test on Value Chain and Competitive StrategyXiao HoNo ratings yet

- A O E I U U: 19 Basic Finals 1, 6 Single FinalsDocument1 pageA O E I U U: 19 Basic Finals 1, 6 Single FinalsXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Is2136 ch1-3Document36 pagesIs2136 ch1-3Xiao HoNo ratings yet

- 23 InitialsDocument1 page23 InitialsXiao HoNo ratings yet

- ACC101 Chapter9newDocument19 pagesACC101 Chapter9newXiao HoNo ratings yet

- Trainer Tools Basic Customer Care Case StudyDocument5 pagesTrainer Tools Basic Customer Care Case StudyXiao HoNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- PRETEST: What Do I Already Know?Document7 pagesPRETEST: What Do I Already Know?Angelina KusumaNo ratings yet

- 2014 ANSI-PRCA 1.0-.3 - 2014 Sect 1.0 3-3-14Document26 pages2014 ANSI-PRCA 1.0-.3 - 2014 Sect 1.0 3-3-14Joy Dawis-AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Kinard Student Leadership Travel Application 2020-2021Document10 pagesKinard Student Leadership Travel Application 2020-2021api-445487848No ratings yet

- All Rights Reserved For You (PDFDrive)Document114 pagesAll Rights Reserved For You (PDFDrive)Himanshu Pravin MoreNo ratings yet

- ZipSTOP Manual HeadrushtechDocument90 pagesZipSTOP Manual HeadrushtechdkklutseyNo ratings yet

- AK G04-English Practice Worksheet-Term 2Document15 pagesAK G04-English Practice Worksheet-Term 2Popular Copy centreNo ratings yet

- Premium Adventure Tech Made in USADocument11 pagesPremium Adventure Tech Made in USAArtur BuarqueNo ratings yet

- Thunderbird Park TreeTop ChallengeDocument2 pagesThunderbird Park TreeTop ChallengePeterNo ratings yet

- The Hidden Castle Resort's PPT-compressedDocument45 pagesThe Hidden Castle Resort's PPT-compressedakshar.vusthelaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Safety and Rescue in Adventure Sports PDFDocument7 pagesGuidelines For Safety and Rescue in Adventure Sports PDFkiki240No ratings yet

- Elements of The ChallengecourseguidebookDocument7 pagesElements of The Challengecourseguidebookapi-591735936No ratings yet

- Astm F2959-16Document9 pagesAstm F2959-16ReliantNo ratings yet

- Fun Facts School WorldDocument6 pagesFun Facts School Worldrealshadow641No ratings yet

- World's Longest Island-to-Island Zipline in Sablayan, Occidental MindoroDocument1 pageWorld's Longest Island-to-Island Zipline in Sablayan, Occidental MindoroPrinzei Ann de RealNo ratings yet

- 10th - 8 Tourist Attractions Offered by Costa Rican CommunitiesDocument22 pages10th - 8 Tourist Attractions Offered by Costa Rican CommunitiesCarlos Torres QuesadaNo ratings yet

- Zipline Reference 3Document11 pagesZipline Reference 3Jomo-Rhys GilmanNo ratings yet

- Ecotourism Facilities-1Document42 pagesEcotourism Facilities-1Zyrone EsguerraNo ratings yet

- Jamaica Takeaway INTERACTIVE WEBDocument17 pagesJamaica Takeaway INTERACTIVE WEBZineil BlackwoodNo ratings yet

- Designing A ZiplineDocument4 pagesDesigning A ZiplinemohsenNo ratings yet

- Peralatan Dasar Flying Fox GamesDocument5 pagesPeralatan Dasar Flying Fox GamesBahrul Ilmi Suprayogi0% (1)

- Different Types of Recreational ActivitiesDocument26 pagesDifferent Types of Recreational ActivitiesJorim SumangidNo ratings yet

- Longest Zipline in KeralaDocument3 pagesLongest Zipline in KeralaLock Your TripNo ratings yet

- Astm F2959-18Document29 pagesAstm F2959-18Martin TapankovNo ratings yet

- Zip Line: Standard Operating ProcedureDocument4 pagesZip Line: Standard Operating ProcedureLemmor BayanNo ratings yet

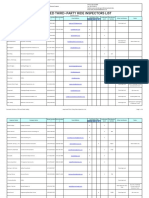

- Amusements Third Party Inspectors ListDocument6 pagesAmusements Third Party Inspectors ListPeteNo ratings yet

- Test 5Document7 pagesTest 550premahuNo ratings yet

- Chazzie ResortDocument28 pagesChazzie ResortJustine DGNo ratings yet