Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Final Stress

Uploaded by

Aditya SharmaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Final Stress

Uploaded by

Aditya SharmaCopyright:

Available Formats

Stress

Stress can be a reaction to a short-lived situation, such as being stuck in traffic. Or it can

last a long time if you're dealing with relationship problems, a spouse's death or other

serious situations. Stress becomes dangerous when it interferes with your ability to live a

normal life over an extended period. You may feel tired, unable to concentrate or irritable.

Stress can also damage your physical health. Stress is a reaction to change; it can be either

positive or negative, and it affects both the body and the mind. Normally, stress stimulates

the release of hormones such as adrenaline, quickening the heart rate, accelerating the

metabolism, and generally preparing the body for emergency action--whether or not the

opportunity for action exists. Stress can destroy a promising academic session, not only

killing the joy of learning but seriously affecting a student's general health and scholarly

performance. Recognizing the sources and the effects of stress as early as possible is

crucial to coping with it.

Stress is the term used to describe the physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral

responses to events that are appraised* as threatening or challenging. Stress can show

itself in many ways. Physical problems can include unusual fatigue, sleeping problems,

frequent colds, and even chest pains and nausea. People under stress may behave

differently, too: pacing, eating too much, crying a lot, smoking and drinking more than usual,

or physically striking out at others by hitting or throwing things. Emotionally, people under

stress experience anxiety, depression, fear, and irritability, as well as anger and frustration.

Mental symptoms of stress include problems in concentration, memory, and decision

making, and people under stress often lose their sense of humor.

Most people experience some degree of stress on a daily basis, and college students are

even more likely to face situations and events that require them to make changes and adapt

their behavior: Assigned readings, papers, studying for tests, juggling jobs, car problems,

relationships, and dealing with deadlines are all examples of things that can cause a person

to experience stress. Some people feel the effects of stress more than others because what

is appraised as a threat by one person might be appraised as an opportunity by another.

(For example, think of how you and your friends might respond differently to the opportunity

to write a 10-page paper for extra credit in the last 3 weeks of the semester.) Stress-causing

events are called stressors; they can come from within a person or from an external source

and range from relatively mild to severe.

STRESSORS - Events that can become stressors range from being stuck behind a person

in the 10-items-or-less lane of the grocery store who has twice that amount, to dealing with

the remains left after a tornado or a hurricane destroys ones home. Stressors can range

from the deadly serious (hurricanes, fires, crashes, combat) to the merely irritating and

annoying (delays, rude people, losing ones car keys). Stressors can even be imaginary, as

when a couple puts off doing their income tax return, imagining that they will have to pay a

huge tax bill, or when a parent imagines the worst happening to a teenage child who isnt

yet home from an evening out. Actually, there are two kinds of stressors: those that cause

distress, which occurs when people experience unpleasant stressors, and those that cause

eustress, which results from positive events that still make demands on a person to adapt or

change. Marriage, a job promotion, and having a baby may all be positive events for most

people, but they all require a great deal of change in peoples habits, duties, and often

lifestyle, thereby creating stress. Hans Selye (1936) originally coined the term eustress to

describe the stress experienced when positive events require the body to adapt. In an

update of Selyes original definition, researchers now define eustress as the optimal amount

of stress that people need to promote health and well-being. The arousal theory is based on

the idea that a certain level of stress, or arousal, is actually necessary for people to feel

content and function well (Zuckerman, 1994). That arousal can be viewed in terms of

eustress. Many students are aware that experiencing a little anxiety or stress is helpful to

them because it motivates them to study, for example. Without the arousal created by the

impending exam, many students might not study very much or at all. What about the

student who is so stressed out that everything hes studied just flies right out of his head?

Obviously, a high level of anxiety concerning an impending exam that actually interferes

with the ability to study or to retrieve the information at exam time is distress. The difference

is not only in the degree of anxiety but also in how the person interprets the exam situation.

A number of events, great and small, good and bad, can cause us to feel stressed out.

STRESS TYPES

Acute stress

Acute stress is the most common form of stress. It comes from demands and pressures of

the recent past and anticipated demands and pressures of the near future. Acute stress is

thrilling and exciting in small doses, but too much is exhausting. A fast run down a

challenging ski slope, for example, is exhilarating early in the day. That same ski run late in

the day is taxing and wearing. Skiing beyond your limits can lead to falls and broken bones.

By the same token, overdoing on short-term stress can lead to psychological distress,

tension headaches, upset stomach and other symptoms.

Fortunately, acute stress symptoms are recognized by most people. It's a laundry list of

what has gone awry in their lives: the auto accident that crumpled the car fender, the loss of

an important contract, a deadline they're rushing to meet, their child's occasional problems

at school and so on.

Because it is short term, acute stress doesn't have enough time to do the extensive damage

associated with long-term stress. The most common symptoms are:

Emotional distress some combination of anger or irritability, anxiety and depression, the

three stress emotions.

Muscular problems including tension headache, back pain, jaw pain and the muscular

tensions that lead to pulled muscles and tendon and ligament problems.

Stomach, gut and bowel problems such as heartburn, acid stomach, flatulence, diarrhea,

constipation and irritable bowel syndrome.

Transient over arousal leads to elevation in blood pressure, rapid heartbeat, sweaty palms,

heart palpitations, dizziness, migraine headaches, cold hands or feet, shortness of breath

and chest pain.

Acute stress can crop up in anyone's life, and it is highly treatable and manageable.

Episodic acute stress

There are those, however, who suffer acute stress frequently, whose lives are so disordered

that they are studies in chaos and crisis. They're always in a rush, but always late. If

something can go wrong, it does. They take on too much, have too many irons in the fire,

and can't organize the slew of self-inflicted demands and pressures clamoring for their

attention. They seem perpetually in the clutches of acute stress.

It is common for people with acute stress reactions to be over aroused, short-tempered,

irritable, anxious and tense. Often, they describe themselves as having "a lot of nervous

energy." Always in a hurry, they tend to be abrupt, and sometimes their irritability comes

across as hostility. Interpersonal relationships deteriorate rapidly when others respond with

real hostility. The workplace becomes a very stressful place for them.

The cardiac prone, "Type A" personality described by cardiologists, Meter Friedman and

Ray Rosenman, is similar to an extreme case of episodic acute stress. Type A's have an

"excessive competitive drive, aggressiveness, impatience, and a harrying sense of time

urgency." In addition there is a "free-floating, but well-rationalized form of hostility, and

almost always a deep-seated insecurity." Such personality characteristics would seem to

create frequent episodes of acute stress for the Type A individual. Friedman and Rosenman

found Type A's to be much more likely to develop coronary heat disease than Type B's, who

show an opposite pattern of behavior.

Another form of episodic acute stress comes from ceaseless worry. "Worry warts" see

disaster around every corner and pessimistically forecast catastrophe in every situation.

The world is a dangerous, unrewarding, punitive place where something awful is always

about to happen. These "awfulizers" also tend to be over aroused and tense, but are more

anxious and depressed than angry and hostile.

The symptoms of episodic acute stress are the symptoms of extended over arousal:

persistent tension headaches, migraines, hypertension, chest pain and heart disease.

Treating episodic acute stress requires intervention on a number of levels, generally

requiring professional help, which may take many months.

Often, lifestyle and personality issues are so ingrained and habitual with these individuals

that they see nothing wrong with the way they conduct their lives. They blame their woes on

other people and external events. Frequently, they see their lifestyle, their patterns of

interacting with others, and their ways of perceiving the world as part and parcel of who and

what they are.

Sufferers can be fiercely resistant to change. Only the promise of relief from pain and

discomfort of their symptoms can keep them in treatment and on track in their recovery

program.

Chronic stress

While acute stress can be thrilling and exciting, chronic stress is not. This is the grinding

stress that wears people away day after day, year after year. Chronic stress destroys

bodies, minds and lives. It wreaks havoc through long-term attrition. It's the stress of

poverty, of dysfunctional families, of being trapped in an unhappy marriage or in a despised

job or career. It's the stress that the never-ending "troubles" have brought to the people of

Northern Ireland, the tensions of the Middle East have brought to the Arab and Jew, and the

endless ethnic rivalries that have been brought to the people of Eastern Europe and the

former Soviet Union.

Chronic stress comes when a person never sees a way out of a miserable situation. It's the

stress of unrelenting demands and pressures for seemingly interminable periods of time.

With no hope, the individual gives up searching for solutions.

Some chronic stresses stem from traumatic, early childhood experiences that become

internalized and remain forever painful and present. Some experiences profoundly affect

personality. A view of the world, or a belief system, is created that causes unending stress

for the individual (e.g., the world is a threatening place, people will find out you are a

pretender, you must be perfect at all times). When personality or deep-seated convictions

and beliefs must be reformulated, recovery requires active self-examination, often with

professional help.

The worst aspect of chronic stress is that people get used to it. They forget it's there.

People are immediately aware of acute stress because it is new; they ignore chronic stress

because it is old, familiar, and sometimes, almost comfortable.

Chronic stress kills through suicide, violence, heart attack, stroke and, perhaps, even

cancer. People wear down to a final, fatal breakdown. Because physical and mental

resources are depleted through long-term attrition, the symptoms of chronic stress are

difficult to treat and may require extended medical as well as behavioral treatment and

stress management.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Chenrezig MeditationDocument2 pagesChenrezig MeditationMonge DorjNo ratings yet

- Deictic Projection Speakers Being Able To Project Themselves Into Other Locations, Time or Shift Person ReferenceDocument5 pagesDeictic Projection Speakers Being Able To Project Themselves Into Other Locations, Time or Shift Person ReferencePhan Nguyên50% (2)

- Activity 1:individual ActivityDocument3 pagesActivity 1:individual ActivityErika Mae NarvaezNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan With GAD Integration SampleDocument7 pagesLesson Plan With GAD Integration SampleMae Pugrad67% (3)

- Mechanical Engineering MCQsDocument7 pagesMechanical Engineering MCQsAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation SwapnilDocument88 pagesDissertation SwapnilAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Mahdhya Pradesh Current Affairs 2016 (Jan-July)Document11 pagesMahdhya Pradesh Current Affairs 2016 (Jan-July)Aditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Banking Awareness Guide - 2Document91 pagesBanking Awareness Guide - 2Target BankNo ratings yet

- BTM 503 Module I PDFDocument0 pagesBTM 503 Module I PDFAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Fluid Machine Lab ManualDocument0 pagesFluid Machine Lab ManualBalvinder100% (2)

- Final Stress ModelsDocument9 pagesFinal Stress ModelsAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Stress - Causes and SymptomsDocument4 pagesStress - Causes and SymptomsAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Health and Fitness Awareness in Relation To Eating Habits in The AdultsDocument7 pagesHealth and Fitness Awareness in Relation To Eating Habits in The AdultsAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Dhiraj 2012Document52 pagesDissertation Dhiraj 2012Aditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Mech Engg Paper 1Document20 pagesMech Engg Paper 14nagNo ratings yet

- 8085 Microproceesor - PPTDocument59 pages8085 Microproceesor - PPTShanagonda Manoj KumarNo ratings yet

- Microprocessor 8086 Pins and SignalsDocument3 pagesMicroprocessor 8086 Pins and SignalsRizwan KhanNo ratings yet

- Measurements and Instrumentation Lecture NotesDocument199 pagesMeasurements and Instrumentation Lecture NotesGaurav Vaibhav100% (6)

- 8086 Microprocessors & Peripherals OverviewDocument31 pages8086 Microprocessors & Peripherals OverviewAbdul Qadeer100% (4)

- GROUPDocument7 pagesGROUPAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- CH 17Document81 pagesCH 17Aditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Vtu 5TH Sem Cse DBMS NotesDocument54 pagesVtu 5TH Sem Cse DBMS NotesNeha Chinni100% (1)

- ProfessionalDocument20 pagesProfessionalAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- RDBMSDocument5 pagesRDBMSDeepa DevarajNo ratings yet

- Non Parametric StatisticsDocument20 pagesNon Parametric StatisticsshhanoorNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Motivasi Kerja dan Prestasi Karyawan di Hotel Resty PekanbaruDocument9 pagesHubungan Motivasi Kerja dan Prestasi Karyawan di Hotel Resty PekanbaruMuhamad ApriaNo ratings yet

- HDC CHÍNH THỨC TIẾNG ANH CHUYÊN 2022Document3 pagesHDC CHÍNH THỨC TIẾNG ANH CHUYÊN 2022Hoàng HuyNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Adjectives Comparative and SuperlativeDocument12 pagesLesson Plan Adjectives Comparative and SuperlativeZeliha TileklioğluNo ratings yet

- MCQ MockDocument4 pagesMCQ MockRohit SohlotNo ratings yet

- IT Week1Document11 pagesIT Week1Mustafa AdilNo ratings yet

- COT-RPMS Teacher Rating SheetDocument2 pagesCOT-RPMS Teacher Rating SheetANTONIETA DAGOY100% (1)

- EmtlDocument707 pagesEmtlLaxmiSahithi100% (1)

- Cold Calling 26 AugDocument4 pagesCold Calling 26 AugGajveer SinghNo ratings yet

- Black White Simple Professional Marketing Manager ResumeDocument1 pageBlack White Simple Professional Marketing Manager Resumeapi-707716627No ratings yet

- Evaluation of English Textbook in Pakistan A Case Study of Punjab Textbook For 9th ClassDocument19 pagesEvaluation of English Textbook in Pakistan A Case Study of Punjab Textbook For 9th ClassMadiha ShehryarNo ratings yet

- Managing Stress: Individual vs Organizational ApproachesDocument4 pagesManaging Stress: Individual vs Organizational ApproachesMuhammad Hashim MemonNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Evaluation of Learning Part 3Document3 pagesAssessment and Evaluation of Learning Part 3jayson panaliganNo ratings yet

- Test English - Prepare For Your English ExamDocument3 pagesTest English - Prepare For Your English ExamDrumsoNo ratings yet

- Complexity Theory & Systems Theory - Schumacher CollegeDocument2 pagesComplexity Theory & Systems Theory - Schumacher Collegekasiv_8No ratings yet

- Mechanical Engineer ResumeDocument3 pagesMechanical Engineer ResumeHimanshu ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Perceptual Learning: An IntroductionDocument476 pagesPerceptual Learning: An IntroductionVíctor FuentesNo ratings yet

- Riddle WorksheetDocument2 pagesRiddle WorksheetbhavyashivakumarNo ratings yet

- Siti Asyifa Soraya Noordin - Artikel - Infomasi Karir - Sman1garut PDFDocument17 pagesSiti Asyifa Soraya Noordin - Artikel - Infomasi Karir - Sman1garut PDFSiti AsyifaNo ratings yet

- Leadership Self-AssessmentDocument5 pagesLeadership Self-Assessmentapi-520874386No ratings yet

- Explore Science's History and PhilosophyDocument6 pagesExplore Science's History and PhilosophyPhilip LaraNo ratings yet

- Method For Shifting Focus From Outcome To ProcessDocument2 pagesMethod For Shifting Focus From Outcome To ProcessEduard ShNo ratings yet

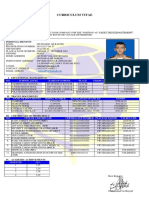

- Curriculum Vitae: To: Crewing Manager Subject: Deck Cadet Application Dear Sir or MadamDocument1 pageCurriculum Vitae: To: Crewing Manager Subject: Deck Cadet Application Dear Sir or MadamWiwit PrihatiniNo ratings yet

- (2010) Handbook Strategy As PracticeDocument367 pages(2010) Handbook Strategy As PracticeViniciusNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in Multicultural PopulationsDocument19 pagesEthical Issues in Multicultural Populationsapi-162851533No ratings yet

- eYRC-2016: Track 1 No Objection Certificate (NOC) FormatDocument2 pageseYRC-2016: Track 1 No Objection Certificate (NOC) FormatManthanNo ratings yet