Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Family at The Fringes - The Medico-Alchemical Careers of J. Ruland & J.D. Ruland

Uploaded by

Acca Erma Settemonti0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

116 views23 pagesThe Ruland family was perhaps the most famous clan involved in alchemy and m edicine in early m o dern Central and Eastern Euro pe. A case in point is the figure of jo hann Dav id Ruland (1605-1648?), who plied his trade in the territory of royal Hungary.

Original Description:

Original Title

Family at the Fringes_ the Medico-Alchemical Careers of J. Ruland & J.D. Ruland

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe Ruland family was perhaps the most famous clan involved in alchemy and m edicine in early m o dern Central and Eastern Euro pe. A case in point is the figure of jo hann Dav id Ruland (1605-1648?), who plied his trade in the territory of royal Hungary.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

116 views23 pagesFamily at The Fringes - The Medico-Alchemical Careers of J. Ruland & J.D. Ruland

Uploaded by

Acca Erma SettemontiThe Ruland family was perhaps the most famous clan involved in alchemy and m edicine in early m o dern Central and Eastern Euro pe. A case in point is the figure of jo hann Dav id Ruland (1605-1648?), who plied his trade in the territory of royal Hungary.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 23

: - ^ : Early

'.. * " s* Science and

*** Medicine

BRILL Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 x v m v .b rill.co m / esm

Fam ily at the Fringes: The Medico-Alchemical Careers

of Jo hann Ruland (1575-1638) and Jo hann Dav id

Ruland (1604-1648?)

Ilona Fekete

Etvs Lordnd University*

Abstract

The Ruland family was perhaps the m o st famous clan involved in alchemy and m edi-

cine in early m o dern Central and Eastern Euro pe. Yet while m ore pro m inent m em b ers

o f the family, such as Martin Ruland Junio r (1569-1611), participated in the alchem -

ical m ilieu at the co urt of Rudo lf II in Prague, o ther m em b ers, farther from the centre

of Em pire, are also significant to the study of interco nnectio ns between early m o dern

alchemy, science, and m edicine. A case in po int is the m isundersto o d figure of Jo hann

Dav id Ruland (1605-1648?), who plied his trade in the territo ries of Royal Hungary.

His major pub licatio n, the Pharmacopoea nova (1644), intro duced the rudim ents of

his "filth-pharm acy" {Dreckapotheke): the use of b o dily waste to cure and heal certain

afflictions. Yet in the seco ndary literature, Jo hann David's life and work have often

been confiised with the activities of his uncle, Jo hann Ruland (1585-1638). The pres-

ent biographical study of b o th Jo hann and Jo hann Dav id seeks to disentangle their

respective intellectual legacies, allo wing us the o ppo rtunity to resituate b o th m en

within their respective medical and alchemical co ntex ts.

Keywords

Jo hann Dav id Ruland, Ruland family, Pressburg (Bratislava), m edicine, Hungary, filth

pharm acy, Dreckapo theke, alchem ical heraldry, pharm acy

* 48 Batthyny Street, 1015 Budapest, Hungary (feketeilo na@yaho o .co .uk). I wo uld

like to thank Do ra Bobory, Leigh Penm an, Rafat T. Prinke, Jennifer Ram pling,

Mrto n Szentpteri and this jo urnal's ano nym o us referee for their assistance, suppo rt

and adv ice.

Koninklijke Brill NV. Leiden. 2012 DOI; 10.1103/10.1163/15733823-I75000A5

/. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 549

A Dreckapotheke from the Ruland Family

Preserved in the Old Print Collection of the Hungarian National

Library (RMK II. 652) is a curious example of so-called "filth phar-

macy," or Dreckapotheke, entitled Pharmacopoea nova. Published in

Leutschau (Levoca/Locse) in the former Kingdom of Hungary in 1644,

its author was a Pressburg-based physician named Johann David

Ruland.' This particular copy is unique, for in addition to its printed

content, its endpapers also bear copious manuscript annotations con-

cerning the practice of filth pharmacy, in the author's own hand. But

although its content, which treads that unusual territory between med-

icine and alchemy, seems strange to modern eyes, stranger still is the

complex historiographical web woven by successive generations of Hun-

garian historians around its author's life and work.

As a prominent member of the famous German medical family, who

spent his life plying his trade in the territories of historical Hungary,

Ruland was an early, and popular, target for patriotic local researchers

of medical history. Yet the nationalistic context of much of this research

has resulted in some egregious errors, not the least of which is the

remarkable conflation of Johann David Ruland (1604-1648?) with his

uncle, Johann Ruland (1575-1638). Subsequently, these errors have

been disseminated into medical history more broadly, a field in which

both Rulands are barely known.^ The only exception to this is a recently

published Hungarian-language article by Mrs Gyrgy Wix, which set

out to solve some of these discrepancies.^

" The Leutschau edition can be viewed online: http://oldbooks.savba.skydigi/mf/

Mf_088/start.htm (accessed 31 July 2012). A further edition was printed in the

same year in Nuremberg by the printer Wolfgang Endter. A copy of this edition is

preserved in Budapest, Hungarian National Library, shelfmark RMK III. 6248. See

also Gyula Magyary Kossa, Magyar orvosi emlkek, vol. Ill (Budapest, 1931), 360.

^' This conflation has also spilled over into significant online resources such as the

VD17 {Das Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahr-

hunderts), where Johann Ruland is incorrectly identified as the son of Martin Ruland

Junior, and not as his brother. See http://gso.gbv.de/DB= 1.28/SET=4/TTL=l 1/SHW?

FRST=15 (accessed 31 July 2012).

' ' Wix Gyrgyne, "Gens Rulandica, egy hires nmet orvoscsald magyar vonatkozsai,"

Communicationes de Historia Artis Medicinae, 170-173 (2000), 121-37.

550 / Fekete I Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569

The present article, drawing on contemporary printed and archival

sources, seeks to disentangle the myths from the reality of the life and

work of both Rulands, and to shed light on the manifold interests and

endeavours of two generations of the Ruland family in East-Central

Europe. It aims to draw attention to the lives of these two significant

members of the Ruland family, and open up several Hungarian

sourcesand archival sources located beyond the former Iron Cur-

tainfor the attention of the medical history community more broadly.

Johann David Ruland: The Historiographical Background

The first significant instance of historical interest in Johann David

Ruland dates back to the eighteenth century, in the person of Istvn

Weszprmi (1723-1799). Weszprmi was a Hungarian physician and

a versatile author of works on obstetrics, paediatrics, inoculation, his-

tory, and medical history. He researched and collected biographies and

bibliographies of Hungarian and Transylvanian physicians in his exhaus-

tive and influential Succinta medicorum Hungariae et Transylvaniae bio-

graphiae, printed in Leipzig between 1774 and 1778. This monumental

collection assembled data concerning physicians not only of Hungarian

origin, but indeed anyone who was active in medical practice in the

territory, including Johann David Ruland. Weszprmi employed a

remarkable range of sources: his own vast book collection, the library

of the Calvinist college in Debrecen, and other materials furnished by

his intellectual circle in Hungary and abroad. In particular, he sought

out several then-unpublished matriculation records, in order to trace

the peregrinatio acadmica of Hungarian students in Jena, Leyden,

Utrecht, Basel, Altdorf, Wittenberg and Heidelberg.''

However, as soon as the researcher follows up some of the most basic

data collected by Weszprmi concerning Ruland's life, several puzzling

and irreconcilable inconsistencies emerge. According to Weszprmi's

sources, Ruland vvas born in Regensburg in 1585, and received his

medical doctorate in Wittenberg, at an unknown date. Thereafter,

Weszprmi claims that Ruland practised as a physician in Pressburg

" Viola Hark, "Azletrajzr Weszprmi Istvn {\72'5-\7^9)," AzOrvosiKnyvtdros,

2 (1974), 137-55.

/. Fekete/Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 551

(Bratislava/Pozsony), where he intermittently held important municipal

positions. Again without pinpointing a specific year, Weszprmi states

that Ruland became court physician of Istvn Bethlen of Iktr (1582-

1648), who in 1622 recommended him to Emperor Ferdinand II for

elevation to the Hungarian nobility. He concludes his account by stat-

ing that Ruland received a second mtac doctorate in Basel in 1629,

as well as studying further in Frankfurt an der Oder. Ruland finally

died in Pressburg at the age of 63, and in the Lutheran cemetery there,

Weszprmi found Ruland's worn tombstone.

In contrast to this complex and confusing picture, in the German

literature Johann David Ruland appears as a son of the famous Martin

Ruland Junior.' According to this literature, Johann David was born in

16O4 and possibly died in 1648, and worked as a physician in Namslau

(Namyslow). Nothing is mentioned of his time in Pressburg. Compared

to the Hungarian sources, data is sparse, but strikingly, the dates of

birth and death, as well as Ruland's place of activity, are completely

different from those communicated by Weszprmi. On the other hand,

one also learns from the German literature that Johann David had an

uncle named Johann Ruland. This Johann was also a physician in Press-

burgand here is a likely explanation for Weszprmi's biographical

confusion. Johann David the nephew and Johann the uncle were both

active as physicians in Lower Austria and the Kingdom of Hungary;

chronologically, their careers in these places indeed overlapped, and

both appear to have had a lasting interest in alchemy. Despite Weszpr-

mi's conflation, the two figures, Johann David and Johann Ruland,

were in fact two very different persons.

Conclusive evidence of this is provided by a little known pamphlet

held in the Preussische Staatsbibliothek Berlin. Entitled Fama posthuma,

and printed in Pressburg in 1640, it consists entirely of panegyrics and

poemata in praise of the career of the famous physician Johann Ruland,

who had died two years previously. Among the many illustrious con-

tributors to this pamphletincluding the philosopher Samuel Butschky

(1612-1678), the jurist Caspar Heuchelin (1571-1626), and the pas-

^' Ulrich Neumann, "Ruland, Martin der jngere," in Neue Deutsche Biographie, 22

(2005), 244; http://www.deutsche-biographie.de/sfz77337.html (accessed 31 July

2012).

552 /. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569

tor Andreas Eccardus (1588-1652), among otherswe also find a

contribution by yet another physician of Pressburg: Johann David

Ruland."^

The Ruland Family

The patriarch of the Ruland medical clan was Martin Ruland Senior

(1532-1602), a professor at the gymnasium in Lauingen (Germany)

and author of philological and lexicographical books. Moreover, he was

a prolific author of medical works that addressed a range of topics and

audiences: school medicine, balneotherapy, practical medicinal cures,

and popular medicine.^

Martin's son, Martin Ruland Junior (1569-1611) was the brother

of Johann Ruland and the father of Johann David. He received his

medical doctorate in Basel, and in 1594 was appointed city physician

of Regensburg. One of his alchemical medicines cured Archduke Mat-

thias of a malady in 1603, and in 1607 he became the personal physi-

cian of Emperor Rudolf IL* For years he had studied the so-called

morbus hungaricus^ the Hungarian disease, which, while working in

France and Spain, he ultimately identified as a variant of typhus. He

devoted a monograph to his discovery: De perniciosae luis ungaricae

tecmarsi etcuratione tractatus (Frankfurt, 1600), which was followed by

a more detailed version a few years later: De morbo ungarico recte cogno-

' ' Fama Posthuma, Quam Viro ... Dn. Johanni Rulando, Medicinae Doctori, Practico

celebrrimo, Physico in libera regiaqfuej dvitate Posoniensi in Ungaria ... Anno Christi

M.DC.IIXL. Aetatis vero LXIII. Mortalitatis legi obsecuto ... Carminibus Epicediis, In

fano Memoriae ... decantatum iverunt Cognatorum, Amicorum & Concivium in Rep.

Literaria ... nomine venientes (Pressburg [Bratislava and Leipzig], 1640).

^' Joachim Telle, "Ruland, Martin d. ," in Walther Killy and Wilhelm Khlmann,

eds., Killy Literaturlexikon. Autoren und Werke des deutschsprachigen Kulturraums, Bd.

10 (Berlin, 2011), 105-6.

*' Benedek Lang, Unlocked Books: Manuscripts of Learned Magic in the Medieval

Libraries of Central Europe (Pennsylvania State University Park, PA, 2008), 276. See

also R.J.W. Evans, Rudolf II and his World: a Study in Intellectual History 1576-1612

(Oxford, 1973); Ivo Purs and Vladimir Karpenko, eds., Alchymie a Rudolf II (Prague,

2011).

" Tibor Gyry, Morbus Hungaricus: eine medico-historische Quellenstudie (Jena, 1901),

45.

/. Fekete/Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 553

scendo etfoeliciter curando, Leipzig 1610.' Somewhat ironically, Ruland

died during a typhus epidemic shortly thereafter, in 1611. He was a

committed follower of Paracelsian philosophy, as appears throughout

his printed works. While best known for his Lexicon Alchemiae (A

Lexicon of Alchemy, or Alchemical Dictionary, containing not only a

full explanation of obscure words and Hermetic subjects, but also the

sayings of Theophrastus Paracelsus')," he also authored the stirring

Propugnaculum Chymiatriae: Das ist Beantwortung und Beschtzung der

Alchymistischen Artzneyen ('The Bulwark of Ghemiatria: That is, a

Response and Defence of Alchemical Medicine') (Leipzig, 1608),'^ and

the posthumously-printed Secreta spagirica ('Spagyrical Secrets') (Jena,

1676). Spagyria is the art of making alchemical medicine, a term intro-

duced by Paracelsus (from the Ancient Greek words "divide" and

"unite"). Its practitioners asserted that the healing power of materia

medica, derived from animal, plant or mineral sources, gains even

greater efficacy through alchemical alteration.'^

Johann Ruland

Johann Ruland, the younger brother of Martin Ruland Junior, was born

in 1575 in Lauingen, Swabia, and died in 1638 in Pressburg. He stud-

ied medicine in Tbingen and Basel, receiving his medical doctorate in

1604 in Basel with a dissertation on menstrual purification.''' Shortly

after gaining his doctorate, he made an entry in the album amicorum

"" Joachim Telle, "Ruland, Martin d. J.," in Killy and Khlmann, eds., Killy

Literaturlexikon, 10: 106-7.

' '' Martin Ruland, Lexicon Alchemiae sive Dictionarium alchemisticum cum obscurorium

verborum et rerum hermeticarum tum Theophrast-Paracelsaricarium phrasium planam

explicationem continens (Frankfurt, 1612).

'^' Telle, "Ruland, Martin d. J.," 106.

' ' ' "For medicine should not deign to believe anything that has not been proven by

fire, tit is] by fire that the physician increases as we have seen. For this reason you

should master alchimia, otherwise known as spagyria." Paracelsus, "Opus Paramirum,"

Liber I, Caput III, in Paracelsus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, 1493-1541.

Essential Theoretical Writings, ed. and trans. Andrew Weeks (Leiden, 2008), 41. See

alsoJ.R. Partington, History of Chemistry, vol. 2. (London, 1969), 134.

"" Johann Ruland, Artis Medicae (Basel, 1604).

554 /. Eekete / Early Science and Medicine 17(2012)548-569

of Caspar Bauhin, Professor of Anatomy and Botany at the University

of Basel.'5

Several sources thereafter mention that Ruland served as city physi-

cian of Pressburg, although, surprisingly, there is no mention of him

in the city's contemporary chamber books {Kammerbcher). Norbert

Duka Zlyomi, a medical historian based in Bratislava, explains this

curious problem as the result of a misinterpretation of the Latin term

in the early literature: instead of Physicus Ordinarius civitatis Posoniensis

(city physician of Pressburg), the correct designation for Ruland might

have been Physicus in civitate Posoninensi ('physician in the city of

Pressburg').'* Zlyomi also notes that it is a mistake to assume that a

city employed a municipal physician continuously throughout the sev-

enteenth century. His research suggests that such physicians were com-

missioned on an ad hoc basis; a position which seems amply borne out

in the case of Ruland, since archival evidence demonstrates that he held

at least two separate commissions in Pressburg, in 1609 and 1611."'

According to the Hungarian medical historian Lszi Szathmry, in

1611, Ruland was forced to step down from his office as city physician

on account of the activities of his "enemies" in the city."*

Szathmry's statement apparently originates from a misreading of

the following entry in the logbook of the Pressburg city council:

Concerning the application of Doctor Johann Ruland against his libellers, who

did behind his back falsely declaim his medicines and deride him, it is decided

that although he shall not receive compensation, he is welcome to continue to

serve the rest of the year in the office of city physician, if indeed he wishes to

remain and practise, and that such a decision shall remain his alone.''^

' " Hans Georg Wackernagel, ed.. Das Matrikel der Universitt Basel, Bd. III (1962),

28; 749.

"*' Norbert Duka-Zlyomi, "Ein rztliches Vademcum der rztefamilie Ruland aus

dem 16. Jahrhundert," Sudhofs Archiv, 61 (1977), 281-97, 282.

"' Norbert Duka-Zlyomi, "The Development of the District Medical Officer in

Hungary from the Middle Ages to the 18* Century," in Wolfenbtteler Forschungen.

The Town and State Physician in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Enlightement

(Wolfenbttel, 1979), 131-40, 135.

' " Szathmry, Lszi, "A magyar iatrokemikusok," A Magyar Gygyszerszettudomdnyi

Tdrsasdg rtesitje (1933), 297-320.

' " "ber Ansuchen des Herrn Doctor Johannes Ruland wider seine Verlumder die

ihm in seiner Cur hinterrcks flschlich ausgeschrien und ihm hchlich verkleinert

I. Fekete I Early Science and Medicine 17(2012) 548-569 555

As this passage demonstrates, Ruland was not dismissed from his posi-

tion but was "welcome to continue" in it, with the caveat that if he

chose to do so, a cash-strapped Pressburg council would not be able to

offer him compensation for the libels he had suffered.

An obituary written by Ruland in 1604, on the occasion of the death

of his friend Ferenc Ndasdy (1555-1604), the so-called 'Black Bey,'

provides additional confirmation of his status as a sometime city physi-

cian in Pressburg, as well as the holder of other officialand largely

honorarytitles throughout the region. Asked to compose the oration

by Ferenc Dersfy, a long-time friend of Ndasdy's, Ruland identified

himself in the text as "the assigned physician of Lower Austria" {illus-

trium Austriae inferioris Medicum ordinarium)} It is worth noting here

that Ruland was evidently very well connected. Ndasdy and Dersfy

were possessors of the two largest latifiindiae (estates) in Pressburg at

this time, indicating that Ruland probably served several highly posi-

tioned persons. Ruland's occasional possession of the title of city physi-

cian in Pressburg is confirmed in the funeral oration written by Josua

Wegelin, the senior minister and priest of the Lutheran church in Press-

burg, following Ruland's death in 1638.^'

It is likely that Ruland spent most of his life in the region of Pressburg

and the Kingdom of Hungary, in the service of th city and the mem-

bers of its elite. Jean Baptiste Morin (1583-1656), a French physician

and astrologer, had met Ruland twice during his travels in the country

in 1614. Morin visited Pressburg while travelling to the famous mining

regions of Upper Hungary, so highly praised by Paracelsus.^^ During

his stay in Pressburg he was called to the home of the Hungarian arch-

beschlossen worden, dass man ihm dieses vollige Jahr noch das Physikatsamt passiren

wolle, wenn er weiter bleiben und prakticiren wolle, solle ihm dies freistehen, doch

ohne Besoldung." Vamossy Istvn, Adatok a gygyszat tortnethez Pozsonyban

(Pozsony, 1901), 22 (citing the original "Protocollum actionale magistratus Civitatis

Posoniensis" of 17 June 1611. l40. 1). All translations are my own unless otherwise

indicated.

^^ Ruland, Oratio Lvctvosa (Kerezmnni 1604), 1-2.

^" Josua Wegelin, AffiiZ/ff cwra /w (Breslau/Leipzig, 1640).

^^' Lszl Andrs Magyar, "Jean Baptiste Morin es Magyarorszg. Egy ismeretlen

Hungarikum" Magyar Knyvszemle, 1 (1998); http://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00021/

00016/0003-eb.html (accessed 31 July 2012).

556 /. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17(2012)548-569

bishop, Ferenc Forgch (1566-1625), to give the ailing churchman

medical and astrological advice. The archbishop's personal physician at

that time was none other than Ruland. Given that the archbishop passed

away the following year, it appears that the consultation, and the pre-

scribed treatment, were unsuccessful. For Morin, the summons to Press-

burg would prove fruitful, for he received gifts from several nobles

present at the Archbishop's court." Morin met Ruland for a second

time in Schemnitz (Banska Stiavnica/Selmecbnya), where Ruland also

held the title of physician of the mining city.^''

In reconstructing Johann Ruland's career from a variety of sources,

we can therefore set some solid milestones: he was physician of Lower

Austria-Pressburg in 1604, city physician in Pressburg between 1606-

1609 and again in 1611, and possibly later as well. In early 1614, he

was at Forgch's court, and during 1614-15 he practised as a physician

in Schemnitz.^'

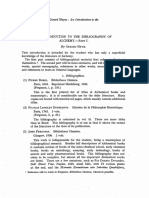

A contemporary engraved portrait of Johann Ruland has survived,

which he evidently commissioned personally from the painter Lukas

Kilian in 1623 (Fig. 1). Kilian (1579-1637), of the famous artisan

family in Augsburg, was mainly employed by noble and royal families

throughout northern and central Europe, although we also find a por-

trait of Pter Pzmny (1570-1637), the Hungarian Cardinal from

1616 to 1637, among his works.^* Ruland probably commissioned the

portrait in order to distribute it among his friends and acquaintances.

It could have been placed in alba amicorum, or commonplace books,

which were often possessed by peregrinating students. The portrait is

indeed used in such a way in the album amicorum of Adam Harel. The

little-known Harel, who later became the court physician to Charles II

-'' Jean-Baptiste Morin, Astro logia Gallica (The Hague, 1661). Book 23: Revolutions,

trans. James Herschel Holden (Tempe, AZ, 2002), 45.

-'" Magyar, "Jean Baptiste Morin."

^'' Johann Ruland signed the Stammbuch of Ulrich Reutter, mine administrator in

Schemnitz in September 1615: Lotte Kurras, ed., Kataloge des Germanischen National-

museums Nrnberg, Die Handschriften des Germanischen Nationalmuseum Nrnberg,

vol. 5: Die Stammbcher (Wiesbaden, 1988), 20.

^'^' Bernt von Hagen and Irene Haberland, "Kilian," in Grove Art Online, Oxford Art

Online (2007-2012), http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/

T046533pgl (accessed 31 July 2012).

/. Feket/Early Science a-id Medicite 17 (2012) 548-569

557

Figure 1: Joannes Rtikind. Line engra^-ing by Lucas Klian, 1623. (Credit: Wellcome

Library, London)

(1630-1685) during his French exile, studied in Vienna between July

1624 and March 1625. It was in Vienna tkat he received the portrait,

and his album also cor tainied manuscript entry from Ruland himself:

Theologians have wririen [he Wcjd of God, Juiiuts their laws: it is irreverent to

depart from the ons; frc^m the other, a crime. T-ue Physicians are nothing like

this, but: their aniy reasoning is experime.Tiririg :or which they strive in funda-

558 /. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569

mentals, and if old and new books are avoided it is not disapproved, because the

truth is more important than the place of authority.-^

On the basis of this inscription, Norman Moore has suggested that

Ruland could have been one of Harel's professors in Vienna.^* Further-

more, Ruland's contemporary biographer, the pastor Josua Wegelin,

mentioned Ruland's 'practice' (of medicine?) at the Faculty in Vienna,

which supports further the possibility that Ruland may have been asso-

ciated with teaching at that institution.

One of the most interesting features of the portrait, however, which

openly presents Ruland as an interested practitioner of the alchemical

arts, is the unusual symbolic coat of arms featured in the top right hand

corner of the image. In 1608, when Martin Ruland Junior was personal

physician to Rudolf II, the Emperor conferred upon all members of the

Ruland familyincluding his brothers Valentin, Otto-Heinrich, and

of course Johanna patent of nobility, which confirmed and extended

the noble title given to Martin Senior in 1559.^'The patent allowed

for the improvement or renovation of the family's coat of arms, which

was duly undertaken.^" As can be seen in the figure, the design depicts

two male figures, each holding in his arms a pair of snakes. This image

probably derives from the famous myth of Hercules. Hera wanted to

destroy the baby Hercules by sending two poisonous snakes into his

cradle, but the infant strangled them with his bare hands. In alchemical

symbolism, Hercules was often employed as a mythoalchemical substi-

"' "Habent theologi Verbum Dei scriptum, Jurisconsuiti suas Leges: ab illo recedere

impium est: ab hisce piaculum. Medici vero nil tale, sed solam rationem experimen-

tiam, quibus pro fundamento nitantur, habent quibus si Veterum aut Neotericorum

scripta dclinent, non improbandum, sed veritati potius quam authoritati locum

denus." Cited in Norman Moore, "The Album Amicorum of Adam Harel and Other

Papers of Christian Harel," in Four Tracts by Norman Moore 1913-1914 {\9\A) [British

Library, Cen ref 11853.c22 (2)].

^^ C.W. Bingham, "MS. Commonplace Book of a German Apothecary," Notes &

Qm (1880), 411.

^" Neumann, "Ruland," 244.

^'" Pavel Horvth, "Nobilitcia a erby lekrov na slovensku v prvej polovici 17.

storocia," Genealogicko-heraldicky hlas, 1 (2000), 17-22; 19. Otto-Heinrich Ruland

utilised the design in a wax seal he used to close a private letter in 1645.

/. Fekete/Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 559

tute for the laboratory operator.^' The image certainly appears to have

maintained alchemical associations throughout the seventeenth-cen-

tury, and a depiction of Hercules strangling the snakes can also be found

on the title page of Goosen van Vreeswyk's De goude leeuw, of den asijn

der wysen ("The Golden Lion, or the Vinegar of the Wise") (Amsterdam

1676).3^

Ruland's personal alchemical proclivities are also on display elsewhere

in the portrait, as in the depiction of distillation equipment on the table

in the foreground. On the flask in his hand appears the words, "Sepa-

rate et ad maturitatem perducite" ("separate and bring to ripeness").

This phrase is emblematic of the Paracelsian medico-alchemical system,

and is reproduced in several famous alchemical works, including the

title page of Oswald Croll's Basilica Chymica (1609). The double motif

could lend further meaning to the coat of arms: implying tension, equal

opponents, and symmetry.

The use of alchemical symbolism in heraldic arms was not excep-

tional in Ruland's time, and indeed, seems to have been a relatively

common practice among physicians connected with the Rudolfine

court. While, as RafatT. Prinke has shown, even hereditary arms may

have been intended to be interpreted in hermetic terms, it is clear that

some alchemists adopted their own overtly alchemical arms, regardless

of whether their noble status was inherited or recently conferred.^^ In

1609, for example, the court physician and alchemist Michael Maier

received the title of Count Palatine from Matthias II. Maier himself

made a request for the symbol of his coat of arms: a toad and an eagle

linked by a golden chain.^'' In his request, Maier invoked his source,

Avicenna's Porta Elementorum, in which the flying eagle denotes com-

mon silver, and the crawling toad represents the fixed property of the

"* Joachim Telle, "Mythologie und Alchemie. Zum Fordeben der antiken Gtter in

der frhneuzeitlichen Alchemieliteratur," in Rudolf Schmitz and Fria Krafft, eds.,

Beitrge zur Humanismusforschung, 6 (Boppard, 1980), 135-54.

^^' The engraved title page shows 1676, but the typographical tide page gives 1675 as

the date.

") RafatT Prinke, "Hermetic Heraldry," The Hermetic Journal, 43 (1989), 62-78;

http://www.levity.com/alchemy/hermhera.html (accessed 31 July 2012).

'" Hereward Tilton, The Quest for the Phoenix: Spiritual Alchemy and Rosicrucianism

in the Work of Count Michael Maier (1569-1622) (Berlin and New York, 2003), 78.

560 /. Fekete I Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569

earth: both properties, and the tension between them, were necessary

for achieving the hermetic medicine and the philosopher's stone.^^ The

result is a fusion of his hereditary crest with one of overt hermetic

symbolism. Maier's coat of arms is a vibrant example of the hermetical

and emblem symbolism rife at the Prague court, and one which may

have inspired the Rulands to adopt an openly alchemical motif in their

own familial arms. Another contemporary and apparently deliberate

hermetic motif in a coat-of-arms, also connected with the Rudolfine

court, is that of Cornelius Petraeus, about whom little is otherwise

known. This shows a figurai representation of Mercury tethered on one

side by a heavy weight, referring to the fixed principle, while the other

side shows wings attached to his hand and leg, symbolic of the volatile.^''

Since Cornelius dedicated an alchemical manuscript to Rudolf II as

both Bohemian and Hungarian King, this must have been written

beforel 608.3^

The upper left corner of the Ruland portrait features another well

known alchemical symbol, in the form of a medallion. The text around

the rim of the medallion states: ()uod est inferius est sicut quod superius,

et quod est superius est sicut quod est inferius"That which is below is

as that which is above and that which is above is as that which is below."

This sentence derives from one of the key tenets of the hermetic tra-

dition, the second line of the Emerald Tablet ( Tabula Smaragdina)

attributed to the legendary Hermes Trismegistus.'* The motto in the

medallion explains the unity of the micro- and microcosm, represented

by the Moon and the Sun, sea and shore, as depicted in the emblem.

The tetrahedron in the middle of the medallion may be intended to

represent any number of triads, including the three Paracelsian princi-

ples, mercury, sulphur and salt; or indeed the holy trinity.

' " Joachim Telle, Buchsignete und Alchemie im XVI. und XVII. Jahrhundert. Studien

zur frhneuzeitlichen Sinnbildkunst (Hrtgenwald, 2004), 75-78.

3 Prinke, "Hermetic Heraldry," 74.

"' Raimon Arla, Images cabalistiques et alchimiques (Paris, 2003); http://www.

arsgravis.com/detall.php?id=193 (accessed 31 July 2012).

^'" The original sentence reads: Quod est inferius est sicut quod est superius, et quod est

superius est sicut quod est inferius, ad perpetranda miracula rei unius"That which is

below is as that which is above, and that which is above is as that which is below, to

perform the miracles of the one thing." Lazarus Zetzner's heirs (pub.), Theatrum

Chemicum, vol. Ill (Strassbourg, 1659-1661), 158.

/. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 % 1

There is little evidence concerning Johann Ruland's activities after

around 1623. According to Weszprmi, Ruland was made court physi-

cian to Istvn Bethlen of Iktr (1582-1648), and it was Bethlen who

recommended Ruland for ennoblement to Ferdinand II, which was

duly confirmed in 1622.^'While this is possible, it seems unlikely that

Johann could have served as a court physician at Bethlen's Transylvanian

court in Alba Iulia (Karlsberg/Gyulafehrvr), and there is no cor-

responding record of Ruland's presence at Bethlen's court. Ruland's

nobility could then be explained as a gesture of thanks from Bethlen

following the peace of Nicolsburg in 1621. It may or may not be sig-

nificant, however, that Jzsef Ernyey has looked for evidence of Ruland's

award of Hungarian nobility in the famous papers of Ivan Nagy,"*" but

has found no evidence of the conferral of title.'"

By 1638, Ruland was again dwelling in Pressburg, still serving as a

physician. His reputation was such that he apparently attracted custom-

ers from across the region. Johann Permeier ( 1597-c. 1644), an Austrian

prophet resident in Vienna who suffered from a condition he described

as "fliges Haupt" (coryza, or allergic rhinitis)''^ mentions travelling

to Pressburg on several occasions in order to visit Ruland to acquire the

physician's pills for relief Permeier, who evidently knew Ruland person-

ally, states that although he "holds the master or maker [of these pills]

for a conscientious and honourable man,'"*^ his choice to travel to Press-

burg from Vienna was primarily due to the efficacy of Ruland's purga-

tive medication, the so-called Rulandischen Pilulen. For, as Permeier

later stated, "no other medicine has ever before helped me so much in

this affliction.'"'''

' " Istvn Weszprmi, Succinta medicorum Hungariae et Transylvaniae biographia

(Lipsiae, 1774-1787), 158.

'"" Nagy Ivan, Magyarorszdg csalddai czimerekkel es nemzkrendi tdbldkkal (Pest, 1857-

1868).

"' Jzsef Ernyey, "Rulandus Pharmacopoeaja 1644," Gygyszerszeti Hetilap, 7 (1898),

98-100; 8 (1898), 114-16; at 98.

''^' Max Hoer, Deutsches Krankheitsnamen-Buch (^erVm, 1899), 162.

''^' "Ich ihren Meister oder Macher fur einen gewihafften vnd redlich Mann gehalten

habe." Halle, Archiv der Franckeschen Stiftung, B17a, III6d (Letter of Permeier to

Melchior Beringer, 3 October 1638). I would like to thank Leigh Penman for sharing

this information with me.

''''' "Mir vorhero niemalen kein medicamentum in disem Zuestand so weit gedienet

562 /. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569

In addition to a private practice, Ruland may have been called upon

again to serve as city physician in Pressburg, as council funds allowed.

He was buried in Pressburg in November 1638. Besides his funeral

oration by Josua Wegelin, his tombstone survived into the eighteenth

century. Istvn Weszprmi made a record of the epitaph, which he

incorrectly connected to Johann David Ruland:

See the Traveller^Johann Ruland, the most successful physician, from the most

noble Quartus[?] familyburied here. [Although] he stitched together everything

mortal, this stone of solemnity does not capture the immortal qualities of the soul.

He lived sixty-three years, and died on 17 October.'"

Johann David Ruland

Having recovered and established the basic trajectory of Johann

Ruland's career, let us now turn to the details available concerning his

nephew. Johann David was the son of Martin Ruland Junior. He was

born in Regensburg in 1604, while his father was practising as the city's

physician. He attended the University of Wittenberg, where he de-

fended his medical dissertation, DeScabie, in 1630. Several years later,

in 1636, he acquired a doctorate in philosophy from the renowned

University of Frankfurt/Oder, this time concerning venereal disease.

Between 1630 and 1631, Johann David worked in and around Nam-

slau, Silesia (Namyslow, Poland), although there is no firm evidence to

demonstrate that he worked there as a field surgeon, as Pavel Horvth

has claimed.""^ During his life he worked mainly in Pressburg and its

environs: a receipt concerning acceptance of his medical services has

survived from 1637, addressed to Cristoph Teufel, public notary in

Leutsche (Levoca/Locse/Lewocza, Slovakia).''^

hat." Halle, Archiv der Franckeschen Stiftung, B17a, III6d (Letter of Permeier to

Melchior Beringer, 3 October 1638).

''** "Vides Viator /Ioannis Rulandi/ Medici felicissimi/ Ex nobilissima hac prosapia

Quarti/ Hie sepositum/ Quicquid mortale suit/ Sed immortales animi dotes/ Haec

lapidis augustia non capit./ Vixit annos LXIII/ Obiit (a.d.?) XVI. Kal. Novembr."

Weszprmi, Succinta medicorum, 158.

^^i Horvth, "Nobilitcia," 19.

''^* Gyula Magyary Kossa, Magyar orvosi emlkek III (Budapest, 1931 ), 352.

/. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 563

Johann David Ruland and his uncle Johann were therefore active as

physicians within the same region; indeed, within the same city, for at

least a few years between 1631 and 1638. Their cohabitation in Press-

burg was evidently the source of confusion for Weszprmi and those

historians who took his data at face value. Johann David spent his last

years in Modra (Modern/Modor). The city council invited him to write

a report concerning methods for the protection of the city from plague

during 1644 {Wie man die Pestilenzische I Seuch verhtten soll) which

was eventually printed by the council.'''

With the exception of the publication of his work on filth pharmacy,

Pharmacopoea nova, in 1644, his movements and activities between

1644 and his assumed death in 1648 are unknown. Some, however, are

documented in manuscripts preserved in Slovakian archives. Johann

David wrote the Pharmacopoea nova in Modra, where he was a practis-

ing physician. There, he evidently entered into a series of disputes with

other local physicians. Tense relations between apothecaries and physi-

cians were quite common at that time. In 1644, Ruland made a com-

plaint against the local apothecary, Zacharias Otthonen, who he claimed

was vending illegitimate medicines.''^ His concern with available rem-

edies is also evident from the pharmacopoea that he published in the

same year. Indeed, it is even possible that Ruland's complaint was related

to the marketing of his new book and his promotion of filth pharmacy.

The practice of Dreckapotheke, namely the use of excrement of dif-

ferent animals to produce medicaments, has existed since ancient Egypt.

The so-called Ebers Papyrus (1550 BCE) is the most important Egyp-

tian medical text, and provides some of the earliest evidence for the

practice. Over half of its recipes utilize what German physicians would

later refer to as Dreck, or fermented or decomposing bodily matter,

whether milk, dung, urine, blood, bones or flesh.^'' Although opinions

concerning the active nature of such cures have changed over time, the

use of excreta was based on the simple principle that a repulsive mate-

"' Jrg Meier, llpo Tapani Piirainen and Klaus-Petra Wegera, Deutschsprachige Hand-

schriften in slowakischen Archiven, Bd. 1 (Berlin, 2008), 836. B/M 979.

"' Meier, Deutschsprachige, 865. B/M 1141.

"" Kamal Sabri Koka and Doris Schwarzmann-Schafhauser, Die Heilkunde im alten

gypten (Stuttgart, 2000), 140.

564 /. Fekete/Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569

rial can expel a physical or mental affliction.^' The use of excrement

assumes a magical explanation of the illness, as the result of a curse or

the special character of the animal whose filth was used.

Besides the symbolical and sympathetic uses of different excrement,

urine analysis (uroscopy) served as the defining diagnostic practice of

medieval Europe, requiring careful observation of the volume, odour,

colour and sediments of urine.'^ Quite aside from its well established

use in diagnosis, the observation of urine and experimentation with it

remained of interest throughout the sixteenth century, partly because

of the use of urine in alchemy," but also due to the new iatrochemical

belief that the body's internal chemistry could produce healing remedies

through a kind of animistic life force.'"* Although filth pharmacy was

particularly popular in German-speaking lands during the early modern

period,'^ a certain ambiguity towards the practice reigned during the

Reformation. The rise of lay pharmacies in the sixteenth to eighteenth

centuries reflected social conditions, when too few physicians existed

to service the community. The need for a medical handbook for laymen

is echoed in the subtitle of Ruland's Pharmacopoea nova, stressing that

the work is available those in poverty, in war, in solitude, hunting, in

the country, or on the road.^^

The basic materia medica of seventeenth-century medical practice

were derived from the three worlds of nature: vegetabilia (plants), ani-

' " Josef Schmidt and Mary Simon, "Holy and Unholy Shit: The Pragmatic Context

of Scatological Curses in Early German Reformation Satire," in Jeff Persels and Rssel

Ganim, eds., Eecal Matters in Early Modern Literature and Art (Farnham, 2004), 109-

17; 113.

"' Andrew Wear, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680 (Cambridge,

2000), 121.

"* Dominique Laporte, History of Shit (MIT, 1993), 36; Andrew Wear, "Early Modern

Europe 1500-1700," in Lawrence I. Conrad, Michael Neve, Vivian Nutton, Roy

Porter, and Andrew Wear, eds.. The Western Medical Tradition 800 BC to 1800 AC

(Cambridge, 1995), 207-361, 315.

5'!) Will-Erich Peuckert, Gabalia. Ein Versuch zur Geschichte der magia naturalis in 16.

bis 18. Jahrhundert {Benin, 1967), 249-50.

"' Schmidt and Simon, "Holy and Unholy Shit," 112.

"' The subtitle of Ruland's Pharmacopoea nova reads: "Iam primum edita pro

Pauperibus, Militantibus & omnibus, quibus in Militia, Itineribus, Venationibus,

Rure, Solitudine, vel alibi alia medicamenta non suppetunt."

/ Fekete /Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 565

malia (animals and humans), and mineralia (minerals). However, at the

end of the sixteenth century several new pharmacopea were published,

featuring recipes that utilised minerals and metals, including antimony,

iron, mercury, and phosphorus.^^ Among the ingredients prized for

their efficacy were animalia derived from the human body, such as

pulverised mummy (mumia), fat, bone, faecal matter, urine, blood, hair,

saliva, nail parings and parts of corpses. Paracelsus assumed that the

animalia contained a life force which could be employed in different

ways: the two main methods were transplantation and application.'^

Sometimes a "magnet" was employed in the cure, burdened with the

life force of the client. The magnet could be made from different sub-

stances, such as blood and urine. The most powerful magnetic medi-

cine, according to Paracelsus, was derived "ex stercore humano," out of

human faeces.''

Ruland's introduction to his Pharmacopoea nova states that the signs

of Nature can be read and explained, like a book afforded to humans

by Cod, to exploit the power of their collective intellects."'" Several of

Ruland's major influences are referenced in the introduction to his

Pharmacopoea nova, and help us to trace the genealogy of some of his

ideas and philosophies. For instance, he made several respectful refer-

ences to his teacher, Daniel Sennert (1572-1637). Sennert was a profes-

sor of medicine in Wittenberg, where he also served as dean. He is often

considered to be the person who introduced the study of chymistry, or

chymiatra, to Cerman universities.^' His Institutionum medicae (1611),

based on a canonised humoral pathology, was the most often reprinted

"' Anne-Christian Lux, Die Dreckapothe.ke des Christian Franz Paullini (MA thesis,

Mainz, 2005); http://www.volkskunde-rheinland-pfalz.de/dreckapotheke/seiten/

dreckapotheke.shtml (accessed on 4 October 2011).

"' Nicolaus Martius, Unterricht von der wunderbaren Magie {X^pg, 1719), 97.

' " Paracelsus, Decem Libri Archidoxis (1659), cited in Peuckert, Gabalia, 252; Karl

SudhofF, ed., Theophrast von Hohenheim: Smtliche Werke I, Bd. 3 (Mnchen and

Berhn, 1922-1933), 149.

'"* Cf Charles Webster, Paracelsus. Medicine, Magic and Mission at the End of the Time

(New Haven and London, 2008), 155.

' " Wolfgang Uwe Eckart, "Sennert, Daniel," in Killy and Khlmann, eds., Killy

Literaturlexikon, 10: 763-64.

566 /. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569

medical textbook of the seventeenth century.''^ Sennert knew the con-

temporary medical literature thoroughly, as he demonstrated in his De

chymicorum cum Aristotelicis et Galenicis consensu ac dissensu (Witten-

berg, 1619),'"^ and he was profoundly influenced by Paracelsian alchemy.

Although he incorporated some Paracelsian notions into his works,

Hiro Hirai has argued that his eclectic approach rather sought to

reconcile Paracelsian ideas with Aristotelianism." Other authorities

mentioned by Ruland include Martin Ruland Senior (his grandfather)

and Martin Ruland Junior (his father), as well as several of his uncles,

including Andreas (1575-1638), Valentin (who received his doctorate

in 1608), Otto Heinrich (b. 1613/17), and, finally, the man with whom

he has been so often confused in the historiography: Johann Ruland.

The interest of the Ruland family in filth pharmacy is demonstrated

by a recent archival discovery by Norbert Duka-Zlyomi. Duka has

been able to identify a vademcum manuscript as the work of Martin

Ruland Senior in the Library of the Slovakian Academy of Sciences.*^'

The father compiled this vademcum for his son, Martin. It came into

Johann David's possession only in 1641, not directly after his father's

death, although Duka, following Weszprmi, confused Johann David

with the older Johann, and believed Martin Junior to be only his broth-

er. ^^ At all events, several copropharmacological recipes appear in the

vademcum, including the use of cow Dreck against arthritis, the stone,

inflammation of the joints, or indeed St Anthony's fire.^^

Among his classical influences, Ruland refers to Galen concerning

the effectiveness of human faeces, and Pliny for a testimony to the

power of animal excreta. Yet Ruland also knew and drew upon many

contemporary sources. He cites the work of Pierre Potier/Petrus Poterius

''^' See William R. Newman, "Sennert, Daniel," in Complete Dictionary of Scientific

Biography, vol. 24 (Detroit, 2008), 417-19.

' " Allen G. Debus, The Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the

Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, vol. 2 (New York, 1977), 191.

''" Hiro Hirai, "Atomes vivants, origine de l'me et gnration spontane chez Daniel

Sennert," Bruniana & Campanelliana, 13 (2007), 477-95.

^" Ustredn kniznica Slovenskej akadmie vied, Bratislava, Rkp 254.

'^^ Duka-Zlyomi, "Ein rztliches," 281, referring to a manuscript note on page 5 of

the work "Sum Joannis Davidis Rolandi, Philosophiae ac M.D. Mense Martio anno

D. 1641."

^^' Duka-Zlyomi, "Ein rzdiches," 291.

/. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 567

(1581-1643), a physician in Bologna and follower of Paracelsian phar-

macy, besides those of the prolific Saxon physician and alchemist,

Andreas Libavius (1550-1616).^* Other authors and works cited

include, for instance, Dioscorides and the fourteenth-century Thesau-

rus pauperum. From the sixteenth century Ruland's major source was

Oswald Gbelkover (1539-1616), the court physician of the Count of

Wrttemberg, and the author of a popu.hr Arzneybuch (1589), as well

as Otto Brunfels (1488-1534).<^'

The recipes in the Pharmacopoea nova are grouped according to the

excretum used. The first group contains human faeces and urine, fol-

lowed by the excreta of male and female cows, sheep, goats, pigs, dogs,

cats, mice, horses, donkeys, boars, hares, wolves, deer, roosters, geese,

pigeons, sparrows, swallows, storks, peacocks, and ravens. Ruland usu-

ally does not mix excreta from different animals, or excreta with other

ingredients, but employs them in their 'pure' form. Solid excreta were

used mainly for external use in their original or dry form, although they

were sometimes handled with wine, rose oil, and urine.

As remarked above, the Old Print Collection of the Hungarian

National Library holds a copy of the Pharmacopoea nova which, in

addition to the printed text, includes seventy-two pages of manuscript

notes in Ruland's own hand.^ These contain new medicinal recipes, as

well as notes on clients treated by Ruland between 1644 and 1648; that

is, between the publication of the book and his death. These demon-

strate not only that Ruland practised medicine during this period, but

that his customers included the elite of society in Modra. His patients

included Mihly Kisvrdai, canon of Trynau (Trnava/Nagyszombat, in

present-day Slovakia),''' Count Mattyasovszky,^^ Denes Benitzky,^'

^" Ruland, Pharmacopoea nova, xi; xv.

''" Ibid., xxiii, XXV, xxvii.

'"* Pharmacopoea nova, Hungarian National Library (RMKII. 652). The manuscript

notes feature in two sequences of unnumbered leaves. An initial sequence of five

manuscript pages is bound into the volume before the title page of the Pharmocopoea

nova. A further sequence of 67 pages is found at the conclusion of Ruland's volume.

For ease of reference, I here number the manuscript pages in sequence, from 1-5 and

6-72.

7" RMK II. 652, 32.

"' RMK 11. 652, 64.

^31 RMK II. 652, 25.

568 /. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569

Count Schlick,^'' and Prince Istvn Bethlen.^^The manuscript notes are

of interest not only to historians of medicine or of Hungarian society.

Besides prayers in Gzech and Polish, and an exorcism ritual in Latin, I

also noted lists of religious works and other miscellaneous items, which

could provide insight to historians seeking clues concerning Ruland's

religious proclivities.^""

One of Ruland's great success stories was his use of filth to cure Denes

Benitzky, who was mesmerized by "virgin" Katalin (Catherine), a local

witch or cunning woman. Ruland prescribed a recipe consisting of

human faeces and prayer.^^ Eventually, the curse lifted. Like his uncle,

Ruland also moved in the circles of Upper Hungarian nobility, although

on the basis of his use of filth pharmacy, rather than expertise in

alchemy.

According to German sources, such as Neumann's article in the Neue

Deutsche Biographie, Johann David died in 1648. His own manuscript

proves that he not only carried on with that kind of healing later in his

life, but that he managed to survive it.

Conclusions

Having disentangled the strands of the lives of Johann Ruland and his

nephew Johann David Ruland, it becomes clear that both men are

intriguing figures who deserve broader recognition: not only within the

traditional Hungarian historiography, which has tended to uncritically

perpetuate the mistakes of Weszprmi, but also in the historiography

of European medicine more broadly. Although Johann and Johann

David led similar lives, their fields of endeavour were quite diverse.

Johann received an imperial post shortly after he gained his doctorate,

and by the 1620s was firmly entrenched in the ranks of Hungarian and

imperial nobility, besides being a renowned and successful medical prac-

'" RMKII. 652, 56.

"' RMK II. 652, 3; 59.

'''' Among the works mentionedby Ruland are volumes by Jan Baptista van Helmont,

and an "Opuscula Erasmi Opuscula, Abraham Scultetus," which can be identified as

the Epistolam ad Hebraeos Concionum Ideae (Frankfurt, 1634). RMK II. 652; 71.

7" RMK II. 652, 25-26.

/. Fekete / Early Science and Medicine 17 (2012) 548-569 569

titioner in his adopted town of Pressburg. Johann David also moved in

the world of nobility, and although his connections ultimately oriented

him toward Hungary and the Hungarian nobility, it is unclear whether

he also attained noble rank himself. The Rulands' attitude to alchemy

was similarly defined by their social positions. Johann's alchemical inter-

ests are recorded in his portrait as a measure of his social status, whereas

Johann David's use of everyday cures in his medical practice shows

only a very slight connection to the courtly display of alchemy. Johann

Ruland's portrait suggests a more genteel, rather methodical appro-

priation compared to Johann David Ruland's filth pharmacy, an 'every-

day' and artisanal medical practice for those that required it.

In this article I have sought to bring together data concerning the

lives of Johann and Johann David Ruland, but there are undoubtedly

many more printed works and archival items preserved in Pressburg

and elsewhere, which could contribute to a fuller study of the Rulands'

significance. Exploring these sources can help us map how, over the

course of several generations, members of the family moved between

the "centres" and "fringes" of intellectual, medical, and chymical activ-

ity in East-Central Europe: a movement expressed not only in terms

of their places of employment, but also in the kind of medicine they

practised, and the philosophies which underwrote their manifold ac-

tivities.

Copyright of Early Science & Medicine is the property of Brill Academic Publishers and its content may not be

copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Assumption of Godform (Mark Stavish)Document12 pagesAssumption of Godform (Mark Stavish)metatron2014No ratings yet

- Facial Diagnosis Cell SaltsDocument49 pagesFacial Diagnosis Cell SaltsVitorio Venturini87% (30)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Mystery of The Cathedrals Full OCRDocument129 pagesThe Mystery of The Cathedrals Full OCRNeil100% (2)

- How To Make The True - Elixir of LifeDocument5 pagesHow To Make The True - Elixir of Lifemichael777No ratings yet

- Pierre de Lasenic - Sexual Magic PDFDocument16 pagesPierre de Lasenic - Sexual Magic PDFMathew LoveNo ratings yet

- Alchemy Journal 33-12-136-1-10-20170820Document40 pagesAlchemy Journal 33-12-136-1-10-20170820julian_rosengren100% (5)

- Hellenistic Mysteries and Christian SacramentsDocument37 pagesHellenistic Mysteries and Christian SacramentsAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- 22moons EbookDocument95 pages22moons EbookDaniela HuertaNo ratings yet

- Dawn of The JediDocument224 pagesDawn of The JediPablo Edo Castro0% (2)

- Section 1 VerbalDocument22 pagesSection 1 VerbalLei MaoNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Mysterious Magical OrmusDocument2 pagesMysterious Magical OrmusYourVirtualMediaNo ratings yet

- Jungian Clinical Concepts: 16-Month CourseDocument8 pagesJungian Clinical Concepts: 16-Month CourseValeria AlmadaNo ratings yet

- Alchemical EssaysDocument17 pagesAlchemical Essaysorfikos100% (1)

- English For ChemistsDocument73 pagesEnglish For ChemistsferoNo ratings yet

- J VEENSTRA: The Holy Almandal - Angels & The Intellectual Aims of MagicDocument42 pagesJ VEENSTRA: The Holy Almandal - Angels & The Intellectual Aims of MagicAcca Erma Settemonti100% (2)

- Alchemy - A To ZDocument208 pagesAlchemy - A To ZJose Finnegan100% (4)

- Problems On The Path of ReturnDocument19 pagesProblems On The Path of ReturnPieter B Roos100% (1)

- Alchemist's Supplies - V 1.1: Learning New RecipesDocument5 pagesAlchemist's Supplies - V 1.1: Learning New RecipesBo PostonNo ratings yet

- Blue-Ray Starseed Traits.: WebsiteDocument1 pageBlue-Ray Starseed Traits.: WebsiteLilyCherryNo ratings yet

- KBL Denomination StudyDocument82 pagesKBL Denomination StudyMuc CucuiNo ratings yet

- Waytoblissinthre 00 AshmDocument240 pagesWaytoblissinthre 00 Ashmmagichris100% (1)

- The Corpus HermeticumDocument2 pagesThe Corpus HermeticumAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Verdenius Parmenides' Conception of LightDocument16 pagesVerdenius Parmenides' Conception of LightAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- An Empirical Investigation of Jung's Dream Theory: A Test of Compensatory vs. Parallel DreamingDocument125 pagesAn Empirical Investigation of Jung's Dream Theory: A Test of Compensatory vs. Parallel DreamingAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Books by DR Debasish KunduDocument12 pagesBooks by DR Debasish KunduDebasish KunduNo ratings yet

- Ptolemy On Sound - Harmonics 1.3 (6.14-9.15 Düring)Document38 pagesPtolemy On Sound - Harmonics 1.3 (6.14-9.15 Düring)Acca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Rampling - Transmission and Transmutation: George Riplay and The Place of Alchemy...Document23 pagesRampling - Transmission and Transmutation: George Riplay and The Place of Alchemy...Acca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Science in The Spanish and Portuguese Empires 1500 1800 2008Document454 pagesScience in The Spanish and Portuguese Empires 1500 1800 2008daveybaNo ratings yet

- Chymia Science and Nature in Medieval and Early Modern Europe - PrinkeDocument61 pagesChymia Science and Nature in Medieval and Early Modern Europe - PrinkeAcca Erma Settemonti100% (1)

- Isaac The Alchemist by Mary Losure Chapter SamplerDocument18 pagesIsaac The Alchemist by Mary Losure Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press40% (5)

- Vermaseren The Miraculous Birth of MithrasDocument21 pagesVermaseren The Miraculous Birth of MithrasAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- MANGET Bibliotheca Chemica Curiosa Vol. 1 (2 Voll.)Document1,916 pagesMANGET Bibliotheca Chemica Curiosa Vol. 1 (2 Voll.)Acca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- The Consilia Attributed To Arnau VilanovaDocument47 pagesThe Consilia Attributed To Arnau VilanovaAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- KLEMM Medicine and Moral Virtue in The Expositio Problematum Aristotelis of Peter of AbanoDocument35 pagesKLEMM Medicine and Moral Virtue in The Expositio Problematum Aristotelis of Peter of AbanoAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Breve Commento Di V. Verginelli A A Short EnquiryDocument1 pageBreve Commento Di V. Verginelli A A Short EnquiryAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Albinus' Metaphysics An Attempt at RehabilitationDocument24 pagesAlbinus' Metaphysics An Attempt at RehabilitationAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- The Contemplative Idiom in Chan Buddhist Rhetoric & Indian+Chinese AlchemyDocument82 pagesThe Contemplative Idiom in Chan Buddhist Rhetoric & Indian+Chinese AlchemyAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Blumenthal Plotinus Ennead I.2.7.5 - A DifferentDocument5 pagesBlumenthal Plotinus Ennead I.2.7.5 - A DifferentAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- STILLMAN: Th. B. Von Hohenheim Called Paracelsus 1922Document200 pagesSTILLMAN: Th. B. Von Hohenheim Called Paracelsus 1922Acca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- DISSERT Astronomy Alchemy & Archetypes - Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's DreamDocument192 pagesDISSERT Astronomy Alchemy & Archetypes - Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's DreamAcca Erma Settemonti100% (1)

- Codice Di Commercio 1882 - ItaliaDocument574 pagesCodice Di Commercio 1882 - ItaliaMarcelo Mardones Osorio100% (1)

- Vuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)Document935 pagesVuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)krca100% (2)

- Lifeofphilippust1896hart BWDocument336 pagesLifeofphilippust1896hart BWHasibuan SantosaNo ratings yet

- Don Karr - The Study of Christian Kabbalah in EnglishDocument43 pagesDon Karr - The Study of Christian Kabbalah in EnglishMayro MartinezNo ratings yet

- Vuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)Document935 pagesVuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)krca100% (2)

- SHIRLEY R.: Occultists & Mystics of All Ages 1920Document200 pagesSHIRLEY R.: Occultists & Mystics of All Ages 1920Acca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- HERING: A Catalogue of Very Rare & Curious Collections of ParacelsusDocument32 pagesHERING: A Catalogue of Very Rare & Curious Collections of ParacelsusAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- STRUNZ F.: Th. Paracelsus - Sein Leben Und Seine Persönlichkeit 1903Document153 pagesSTRUNZ F.: Th. Paracelsus - Sein Leben Und Seine Persönlichkeit 1903Acca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Grasshoff Johannes: Der Grosse Und Kleine Bauer (Altra Edizione)Document122 pagesGrasshoff Johannes: Der Grosse Und Kleine Bauer (Altra Edizione)Acca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- FERGUSON J.: Bibliographia Paracelsica 1893Document316 pagesFERGUSON J.: Bibliographia Paracelsica 1893Acca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Biological TransmutationsDocument15 pagesBiological TransmutationsBryan GraczykNo ratings yet

- Ambix 1 - Issue 1.4Document13 pagesAmbix 1 - Issue 1.4Diogo CalazansNo ratings yet

- Hermes and FreemasonryDocument2 pagesHermes and FreemasonrytodayperhapsNo ratings yet

- Zec, Božanska Iskra or Pistis Sophia, IKON 8 2015Document15 pagesZec, Božanska Iskra or Pistis Sophia, IKON 8 2015DanNo ratings yet

- Review MakaraDocument6 pagesReview MakaraSaliniNo ratings yet

- The Quest For The Fulfillment of Destiny:A Study On Santiago in Paulo Coelho's "Alchemist."Document4 pagesThe Quest For The Fulfillment of Destiny:A Study On Santiago in Paulo Coelho's "Alchemist."Chuii MuiiNo ratings yet

- Citations of Jakob BoehmeDocument5 pagesCitations of Jakob BoehmePato LocoNo ratings yet

- Intro To Green HermeticismDocument20 pagesIntro To Green HermeticismHierophageNo ratings yet