Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Porpora (2000) - Personal Heroes

Uploaded by

artemida_0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views22 pagesPorpora (2000)-Personal Heroes

Original Title

Porpora (2000)-Personal Heroes

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPorpora (2000)-Personal Heroes

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views22 pagesPorpora (2000) - Personal Heroes

Uploaded by

artemida_Porpora (2000)-Personal Heroes

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 22

!"#$%&'( *"#%"$+ ,"(-.

-%&+ '&/ 0#'&$1"&/"&2'( 3"2'&'##'2-4"$

5627%#8$9: ;%6.('$ <= !%#>%#'

?%6#1": ?%1-%(%.-1'( @%#6A+ <%(= BB+ C%= D 8E6&=+ BFFG9+ >>= DHFIDDF

!6J(-$7"/ JK: Springer

?2'J(" L,M: http://www.jstor.org/stable/684838 .

511"$$"/: HBNHONDHBB BP:QB

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springer. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Sociological Forum.

http://www.jstor.org

Sociological Forum, Vol. 11, No.

2,

1996

Personal Heroes, Religion, and Transcendental

Metanarratives

Douglas V Porporal

With the increased sociological interest in popular culture, many studies have

examined the hero

types

lauded by the media from situation comedies to

movies, books, and magazines. Few studies,

however,

have examined who, if

anybody,

actual individuals

identify

as personal heroes. To the extent that the

hero identification of individuals has been examined at all, it has generally

been the hero identification of children and adolescents that has been studied.

The study of heroes is important because heroes are one indicator of who we

are and what we stand for That is partly what motivates the recent attention

to the media's identification of heroes. Yet while the media represent a very

visible aspect of culture, who individuals privately cite as their heroes is,

although less visible,

just

as much a part of who we are as a culture.

Accordingly, this paper reports on findings from two telephone surveys

conducted in Philadelphia that, among other questions pertaining to the

meaning of life, asked adults over 18 whether they had any heroes and if so

who those heroes were. The tendency to

identify

with heroes was found to be

related to transcendental concerns with the meaning of life and to religiosity.

Overall, the patten of findings discloses an unstudied dimension of cultural

disenchantment.

KEY WORDS: personal heroes; religion; transcendental metanarratives; moral meaning; iden-

tity.

INTRODUCTION

Do people today have personal heroes-figures with whom they iden-

tify

as personifications of their values and ideals? If so, who are these he-

'Department of Psychology, Sociology, and Anthropology, Drexel University, Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania 19104.

209

0884-8971/96/0600-0209$09.50/0 e 1996 Plenum Publishing Corporation

210

Porpora

roes, and what do they tell us about the values and ideals of the individuals

who identify with them? While considerable scholarly attention has been

paid to the macrocultural heroes promoted by the media, there has been

little research on whom, if anybody, individuals identify as heroes at the

microcultural level.

In the absence of data, conventional wisdom has been divided on the

extent and nature of personal hero identification in contemporary society.2

Some commentators (Becker, 1973; Fishwick, 1983) assume a universal

need for heroes. Others (Glicksberg, 1968; Schlesinger, 1968) lament mod-

ernity's putative loss not just of heroes but of the whole larger sense of

heroic calling often associated with hero identification. Still others (e.g.,

Boorstin, 1968; Lowenthal, 1943) believe personal hero identification has

largely devolved into empty "celebrity worship."

Which of these views is correct, if any? The research presented in this

paper represents an initial exploratory attempt to find out. Specifically, two

phone surveys were conducted in 1993, one in April and one in October.

Each survey (n = 277 and n =

350) asked a random sample of Philadelphia

residents whether they have heroes and, if so, who their heroes are. On

the basis of the data collected, this paper will examine (1) how prevalent

personal hero identification is; (2) the types of heroes identified by those

who have them; (3) who is more or less likely to have personal heroes;

and (4) what light the nature and extent of hero identification sheds on

contemporary values and ideals at the micro, individual level of analysis.

It turns out that personal hero identification is bound up with broader phe-

nomena relating to religion and transcendental metanarratives. Thus, as

will be seen, each of the four aspects of hero identification that will be

examined bear on these broader phenomena as well.

Heroes have been studied more by scholars in

communications, folk-

lore, and American studies than by sociologists, perhaps because until,

fairly recently, sociologists have neglected the study of popular culture. It

ought to be noted at the outset, therefore, that hero identification need

not imply either hero worship or a "big-man" theory of history (Schlesinger,

1958; Schwartz, 1985), although Carlyle (1895) and Hook (1943), with

whom the notion of heroes is often associated, were committed to both.

One may have personal heroes without worshiping them. In such capacity,

heroes are like moral beacons. They function in much the same way as,

according to Eliade (1959), sacred space and sacred time function for homo

religiosus. For homo religiosus, sacred time and sacred space center the

2According to the New American Dictionary, the word hero is now gender neutral and can

refer to women as well as men. Hakanen (1989a), moreover, confirms that female respon-

dents in particular hear the word "hero" as gender neutral. Thus, throughout this paper, the

single word hero is used to designate both male and female heroic figures.

Personal Heroes 211

profane world around them. Similarly, heroes function to center the world

of moral space. They signal to what one is called or committed.

The word hero comes from the Greek heros, meaning "God-person,"

the person charged with the charisma of the holy and sacred, the very

ground of being (Hakanen, 1989b). It is from their connection with what

Tillich (1952) refers to as the ground and core of our being that heroes

derive their charismatic power to inspire (Weber, 1947). Thus, heroes are

not simply role models but charismatic role models (Fishwick, 1983). As

such, a person's heroes are better conceptualized not as idols of worship,

but as an idealized reference group. One seeks to stand with one's heroes

rather than to be one's heroes in actuality, and heroes thus are one mecha-

nism we use to tell ourselves what it is we stand for. For those who have

them, then, heroes are an important inner marker of identity. They are a

part of the landscape of the soul.3

Considerable scholarly attention has been paid to the identity and na-

ture of the heroes presented to us by the media (e.g., Bell, 1983; Hubbard,

1983; Miller, 1986; Rollin, 1983). While there have been some studies that

ask actual individuals who their heroes are, the individuals questioned are

usually children and adolescents (e.g., Balswick, 1982; Hakanen, 1989a).

Only a few previous scholarly studies have examined hero identification

among adults. One (Gardiner and Jones, 1983) examined hero identifica-

tion among prominent figures in education and government. This study

found that such public figures often cite other public figures-both living

and dead-as personal heroes, public figures such as Anton Chekov, Meri-

wether Lewis and William Clark, Winston Churchhill, and John Kennedy

(whose Profiles in Courage likely identified his own heroes). For those who

had them, the heroes identified symbolized such values as humility, integ-

rity, dedication, vision, and courage. Presumably, by identifying with such

heroes, public figures seek to embody the same virtues themselves-or at

least appear to others as seeking to embody them. Do ordinary adults not

in public life have personal heroes? That question never seems to have

been asked directly, and, accordingly, we do not have an answer.4

3People with personal heroes frequently have multiple heroes, forming what Keen (1994: 233)

in describing his own heroes refers to as a "pantheon." Each personal hero may be thought

of as a charismatic role model. Where multiple heroes cohere for a person, as they seem to

for Keen and Beiting (1994), they may form an idealized reference group.

4In the only scholarly attempt to answer this question, Patterson and Kim (1991) asked a

large random sample of adults whether they thought there are any living heroes in America,

and found that only 30% of the population said yes. Unfortunately, we cannot determine

from this question, worded as it is, whether the other 70% of respondents identify with his-

torical figures no longer alive, whether they identify with non-American heroes, or whether

they just have no personal heroes at all.

Since 1947 the Gallup organization has annually asked about the man or woman "living

today" whom respondents most admire. The cumulative results since then were analyzed by

212 Porpora

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HEROES

Why study heroes? For several reasons. First, our selves are con-

structed not only through their location in social space but through their

location in moral space as well. Our identities are always defined, as it

were, in relation to some sense of "the good" (Taylor, 1989). Insofar as

heroes are an embodiment of our values and aspirations (Lubin, 1968;

Warner, 1959), a personification of what we take to be "the good," who

our heroes are reflect who we are, both individually and collectively (Rick-

man, 1983).

The close relationship between heroes and identity is implicit in the

many studies of the heroes identified by the media. Those studies are con-

sidered to be important in part because of what our media's heroes say

about our identity as a culture. They are further presumed to be important

because of the impact of the media on individuals. There is, therefore, all

the more reason to find out who individuals in our culture

identify

as he-

roes. If the media present us with "befuddled" heroes (Bell, 1983; Miller,

1986), sexually stereotyped heroes (Hubbard, 1983), or just celebrities

(Boorstin, 1968), are these the sorts of people that individuals cite as their

personal heroes? We are here presented with a macro-micro question in

the realm of culture that parallels an issue frequently raised with regard

to social structure. What is the macro-micro link between culture as rep-

Smith (1986), who, as in this paper, was attempting to gain insight into Americans' ideals.

Contrary to the expectations of Boorstin (1968) and Lowenthal (1943), Smith found that few

people named entertainers or sports personalities as figures of greatest admiration. Nor, in-

terestingly, did business executives or entrepreneurs figure prominently. Instead, domestic

political leaders were by far the prominent category (accounting for 45% of mentions), es-

pecially incumbent presidents (19% of mentions) and ex-presidents (8% of mentions). While

in 1986 personal acquaintances and religious figures were still minor categories, accounting

for less than 10% of total mentions each, Smith noticed that, over time, mentions in these

categories were on the rise and anticipated further increase in the future.

Although the people we admire certainly also tell us about our values and ideals, admired

people are not the same as heroes. We can admire someone without that person being a

personal hero to us. For a person to be our hero, we ordinarily have to identify with that

person more than we necessarily do with people we just admire. Heroes, therefore, are a

smaller subset of those we admire. How much smaller? It is difficult to say, but some initial

indication is provided by those answering, "Don't know." Throughout the years the Gallup

question has been asked, an average of 35% of respondents have been unable to name anyone

they admire most. In contrast, Patterson and Kim found that 70% could not name any heroes

currently living in America.

It seems likely that a person can admire many people without identifying heroically with

any. It seems likely as well that when we look at the smaller subset of admired people that

constitute our personal heroes, the distribution of responses across categories will be very

different. The sort of analysis that Smith conducted on those we admire still remains to be

done for those we consider our personal heroes.

Personal Heroes 213

resented by the media, which are macrosocial in effect, and culture as it

is lived microsocially in the shared consciousness of individual actors?

There is another reason why the study of heroes is important. The

fate of hero identification has been closely linked with the disenchantment

of the modern world. According to Taylor (1989), one of the salient traits

of modernity is the recession of an orientation toward transcendental ho-

rizons and the affirmation instead of "ordinary life." Up until modernity,

Taylor says, in one form or another, a distinction was always made between

our ordinary life of production and reproduction and a higher calling to a

life oriented around some notion of the transcendental good. Taylor notes

(1989:211) that while the ordinary life of family and work was always a

prerequisite for the pursuit of the transcendental good, a life devoted solely

to the affairs of human maintenance was never historically considered a

"fully human" life at all. Ordinary life was instead but the infrastructure

for the higher calling, distinctive to human beings.

What was considered to be the higher calling varied. In many societies,

it coincided with the honor ethic of a warrior class. For the Greeks, it was

a life devoted to contemplation and participation in the polis. For medieval

Catholics, it was a nonworldly devotion to God. In the enlightenment, it

was a commitment to truth.

Echoing Weber, Taylor argues that with the rise of capitalism and Prot-

estantism, and also with a pragmatic, technological turn in science, all this

changed. Notions of the good ceased to be located in a transcendental

sphere and began to be considered immanent in ordinary life itself. By

modernity, if the good was to be found, it was to be found in commerce,

in work, in family, and in recreation. A distinctly bourgeois sensibility began

to take hold, and in the process, transcendental concerns began to fade.

It may well be that an heroic orientation is part and parcel of an ori-

entation to transcendental notions of the good. According to Campbell's

(1968) heroic monomyth, for example, the hero is one who, in response to

a call, leaves the familiarity of ordinary life to enter a sphere of transcen-

dental conflict; in returning from which, the hero raises the level of ordinary

life itself. The existential implication of this myth is that the hero's journey

is one we are all, in one way or another, supposed to take. Becker (1973)

is certainly of this opinion. According to Becker (1973:1), "our central call-

ing, or main task on the planet, is the heroic." Hero identification, in this

view, is part of what helps lift us to the pursuit of transcendental horizons.

Thus, for Emerson (1940:1), the heroism of great individuals affirms the

potential for heroism in all of us.

Yet, if in modern times there is no transcendental sphere to enter,

then for us perhaps the hero's journey is not a metaphor of psychic sig-

nificance. In that case, we might expect hero identification either to affirm

214 Porpora

the values of ordinary life or if hero identification truly is linked to ideas

of transcendental calling, to be infrequent and peripheral to modern cul-

ture. Perhaps today it will only be those in some sort of public life who

look to heroes for moral orientation.

Modern culture has frequently been indicted for its absence or trivi-

alization of the heroic dimension. It is said to be a shallow, morally bank-

rupt culture without ideals (Rollin, 1983). "We still agree with Carlyle,"

says Boorstin (1968:325), "that 'No sadder proof can be given by a man

of his own littleness than disbelief in great men."' Schlesinger (1968:341)

seconds this judgment: "Let us not be complacent about our supposed ca-

pacity to get along without great men. If our society has lost its wish for

heroes and its ability to produce them, it may well turn out to have lost

everything else as well." "What is wrong with our age," says Glicksberg

(1968:357), "is that it has lost its faith in the greatness or the capacity for

greatness of man."

Perhaps, however, we have not so much lost our faith in human great-

ness as altered our cultural notion of what greatness is. According to

Lowenthal's (1943) analysis of popular magazines, we no longer value "idols

of production" or "doers" but rather "idols of consumption," who relate

to our leisure life. Along similar lines, Boorstin (1968) maintains that he-

roes in modern culture have been replaced by celebrities. Whereas heroes

were famous because they were great, celebrities, Boorstin tells us, are great

because they are famous. "The celebrity," says Boorstin (1968:334) in a

now well-known definition, "is a person who is known for his well-known-

ness." As such, celebrities, unlike traditional heroes, are morally neutral.

According to Boorstin (1968:334), celebrities are "human pseudo-

events," mere "spectacles." A celebrity as a celebrity stands for nothing.

Thus, Boorstin (1968:336) maintains, celebrities are not moral beacons that

"fill us with purpose," but empty "recepticles into which we pour our own

purposelessness." Celebrities, therefore, would seem to be fitting heroes

for an age that, as Lyotard (1984) claims, is without "metanarratives."

Whether the claim is that we have gone from a veneration of moral

heroes to the celebration of mere celebrities or from an affirmation of tran-

scendental purpose to an affirmation of ordinary life, the literature suggests

a longitudinal thesis. Clearly, that thesis cannot be evaluated by the static

data presented here. Consider, for example, Taylor's claim that whereas in

the past, some transcendental purpose was always valued, today it is ordi-

nary life that is affirmed. In the past, the pursuit of any kind of transcen-

dental good was afforded only to the elite few. Women and commoners

were usually excluded from the heroic call. Thus, even if Taylor's account

is correct, it would likely have been only the male elite, who, expected to

respond to a heroic calling themselves, geared themselves for such under-

Personal Heroes 215

taking through hero identification. It is likely, therefore, that had an opin-

ion poll been conducted in the past, we would not find hero identifiction

any more widespread than now, when many more can respond to a heroic

call.

If we cannot, using static data, evaluate theses that are diachronic, we

can, however, transform what were diachronic hypotheses into synchronic

ones. By examining the prevalence of hero identification today, we can cer-

tainly evaluate whether at least a felt need for heroes is universal. By ex-

amining who people cite as personal heroes, we can determine whether

the media's glorification of celebrities-about which Boorstin and Lowen-

thal complain-also manifests itself at the level of individuals. Similarly, by

examining people's personal heroes, we can determine (following Taylor)

whether it is ordinary life or transcendental purposes that people more

tend to value today. We can determine, in other words, whether people

tend to cite ordinary people as heroes more than they do transcendental

figures associated with encompassing metanarratives.

Taylor's hypothesis about the loss of transcendental horizons can be

framed even further synchronically. Cooley (1964), who was evidently fas-

cinated by hero identification, wrote along similar lines himself from a more

synchronic perspective (see Schwartz, 1985). "Hero-worship is a kind of

religion," wrote Cooley (1964:314), 'And religion . . .is a kind of hero-wor-

ship." Cooley, thus, connects hero-identification with religion and other

transcendental metanarratives. For Cooley, hero-identification was precisely

a way for the individual to mark self-transcendent aspirations associated

with moral idealism. Cooley's hypothesis, therefore, may stand in as a syn-

chronic proxy for Taylor's. If Cooley is correct, then we should expect a

relationship between hero-identification on the one hand and religiosity

and other indicators of an orientation toward transcendental meaning on

the other. This and the previously cited synchronic hypotheses are what

this paper will explore.

METHODOLOGY

This project employed a questionnaire, which was administerd through

the university's survey research center. The center utilized random digit

dialing within each of Philadelphia's phone exchanges to secure a random

sample of city residents. To randomize responses further, the questionnaire

was not necessarily administered to the person who answered the phone

but to the household member over 18 who was to have the next birthday.

For both the spring and fall surveys, calls were made between 6:00 and

9:00 PM over four evenings.

216 Porpora

Calls were made by university students as part of methodology courses

in sociology, political science, and communications. In addition to class in-

struction, student participants were given an hour-long training session on-

site on how to conduct the phone interviews. To ensure uniformity of

administration, the first evening's session was videotaped and shown to stu-

dents participating on subsequent evenings.

On the fourth evening, follow-up calls were made to all phone lines

that had previously been busy, where no one had answered, or where the

respondent had requested the interviewer to call back. The final response

rate in the spring was 41% and in the fall 38%. These response rates

yielded a sample of 277 cases in the spring and 350 in the fall for a com-

bined n = 627.

The response rates were below those associated with professional poll-

ing organizations, but even the response rates of the professionals have

been falling over the past few years as telemarketers increasingly represent

public opinion research as a way to make a sale (Spethmann, 1991). The

main problem with such low response rates is the possibility of bias. The

questionnaire was introduced as a "survey about issues of interest to mem-

bers of the Philadelphia area," and the first two questions related to ex-

pectations about the future of Philadelphia and the United States as a

whole. Those refusing to respond, therefore, were not reacting to the spe-

cific subject matter discussed in this paper. Probably the main reason for

the low response rates was the inexperience of the student interviewers.

The demographic characteristics of the two samples are presented in Table

I. As can be seen, the survey underrepresents males-particularly African-

American males, those aged 65, and older, and those with household in-

comes of under $10,000/year. Most substantially underrepresented are

Philadelphia residents without a high school degree. Those with at least a

college degree, accordingly, are overrepresented.

Since the data from the two surveys closely coincided, since there were

no statistically significant differences between the samples on the major

variables, and since the time difference between the two was insufficient

to affect any of the hypotheses under consideration, the two

samples were

combined where possible for purposes of analysis.

The third question in both surveys was, "Do you have any heroes that

you model some aspect of your life around?" If

respondents

said

yes, they

were asked to name one, and if they named one, they were asked if

they

had other heroes.

Heroes were classified under six different types, the first two of which

were directly suggested by the hypotheses. Specifically, "celebrities" encom-

pass sports figures and popular entertainers, those whom Lowenthal refers

to as "idols of consumption." Similarly, "local heroes" are heroes of ordi-

Personal Heroes 217

Table I. Demographics: Combined Survey Data vs. 1990 Philadelphia Censusa

Ageb Survey (%) Census (%) Race Survey (%) Census (%)

18-24 17.9 15.0 White 57.1 53.4

25-34 26.6 23.0 Black 33.1 39.9

35-44 18.5 17.6 Other 98 6.7

44-54 14.5 12.5 N = 582

55-64 8.7 11.9

65 + 13.8 20.0

N = 586

Educationb

(Years) Survey (%) Census (%) Gender Survey (%) Census (%)

0-11 15.5 34.1 Female 61.3 53.5

12 33.7 33.1 Male 38.7 46.5

13-15 19.5 18.2 N = 581

16 15.8 9.1

16 + 15.5 5.5

N = 589

Household Census How

Incomec Survey (%) (%) Religiond Survey (%) Religiousd Survey (%)

<$10k 15.6 23.5 Catholic 35.2 Very 27.3

$10k-$20k 21.3 19.8 Protestant 38.7 Somewhat 50.7

$20k-30k 19.1 17.3 Jewish 6.3 Not Very 22.0

$30k-$50k 24.3 24.6 Other 10.1 N = 551

$50k + 19.7 14.8 Agnostic 2.5

N = 503 Atheist 7.2

N = 57

aSource: U.S. Census Summary Tape File (STF3A-Long Form): Demographic Totals for

Philadelphia County.

bThe base was Philadelphia residents aged 18 and over.

cHigher income categories for survey and census were collapsed to establish comparative

equivalence.

dVariables not reported by U.S. Census.

nary life who are personal acquaintances of the respondent-local socially

if not always spatially. Among others, local heroes included family mem-

bers, particularly the respondents' mother and father-the two heroes most

frequently named; teachers; clergy; and friends.

Four additional categories of hero were employed. Any hero whose

claim to fame resides in the political arena was classified as a "political

hero." Thus, political heroes include Hilary Clinton and Martin Luther

King, Jr. Saints and other exemplary religious figures such as Mother Ther-

esa were classified as "religious heroes." The "arts' is a somewhat hetero-

geneous category that includes scientists such as Einstein or Linus Pauling;

philosophers such as Socrates; and painters, poets, and novelists such as

218 Porpora

Pablo Picasso, Maya Angelou, and Norman Mailer. Heroes not fitting any

of the first five types were classified as "other."

Some of the survey questions pertaining to the meaning of life were

of a philosophical nature that can tax respondents' comprehension more

than questions about concrete behavior. Accordingly, the philosophical

questions in this study were asked in a way that would increasingly sensitize

respondents to philosophical matters. One question, for example, asked re-

spondents how often they thought about the "ultimate meaning of human

existence." Before being asked this question, respondents were read the

following statement:

People sometimes wonder about the meaning of life. Often we think about the

meaning of our own individual life. But we could also wonder whether human

existence in general has any ultimate meaning. How often do you think about the

meaning of your own life and then about the ultimate meaning of human existence

in general?

Respondents were then asked how often they thought about the mean-

ing of their own lives and only then about the meaning of human existence

in general. It turned out as expected that while most people thought a lot

about the meaning of their own lives (making this question a poor discrimi-

nator), considerably fewer thought about the meaning of human existence

in general (making that question as it turned out a good discriminator).

These were the first philosophical questions asked in the spring. In the fall,

people were asked first how important the question of life's meaning was

to them. In both surveys, the more difficult questions about the meaning of

life were placed later, once people had been oriented to the topic.

The quantitative survey data presented here are actually a component

of a larger, much more qualitative study of what people think about the

meaning of life. When in the course of in-depth interviews, few subjects

reported having heroes, it prompted a question about the repre-

sentativeness of the interviewees. That is what led to the survey research

reported on in this paper. From the in-depth interviews, it also became

apparent that many people interpret what a hero is in ways that vary from

the theoretical understanding suggested in the literature. That variance and

its implications will be discussed below.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Prevalence of Hero Identification

In both the spring and fall surveys, only 44% of the respondents said

they had heroes. When the heroes named were examined and invalid re-

Personal Heroes 219

sponses such as "I'm my own hero" were removed, it turned out, again

consistently, that only 40% of the respondents had heroes.

As previously mentioned, in-depth interviews reveal that people often

take personal heroes to be something different from what they are pre-

sumed to be in the theoretical literature. In the literature, personal heroes

are generally considered to be charismatic role models or an idealized ref-

erence group, signifying moral purpose or commitment. On this construal,

one's heroes indicate what one stands for.

Many people do interpret their personal heroes this way. When asked

what the difference is between a hero and a role model, one white female

interviewee, whose heroes included her mother and Dorothy Day, replied

that "a hero is a role model par excellance." Similarly, an African-American

man, whose heroes included Angela Davis, Malcolm X, and Matt Turner,

explained that heroes are people who inspire him to struggle against in-

justice and by whose example, he, himself, attempts to live. It is the putative

loss of such inspirational heroes and the moral horizons they establish that

the theoretical literature laments.

Three other interviewees, who were just as morally and politically com-

mitted, did not have heroes because they interpreted that word as signifying

impossible figures who are morally perfect in all respects. While these in-

terviewees denied having heroes, all three said they have or have had "men-

tors," some of whom are not personal acquaintances. By asking only for

heroes, the survey likely undercounts such people who, if they reject the

word "hero," nevertheless rely on charismatic mentors in a conceptually

close way.

If such people are undercounted by the survey, many others are over-

counted-overcounted if what we are really after is people with personal

heroes by whose moral example they attempt to live. Asked whether they

have heroes, some respondents mention not personal heroes but cultural

heroes-heroes of the group-such as Harry Truman. From in-depth inter-

views, it is clear that such people do not view heroes like Harry Truman

as exemplars around which their own lives are modeled. They mean, rather,

that such heroes have done something praiseworthy for the group to which

they belong. Such heroes are conceptualized in the literature as cultural

rather than personal heroes (see, for example, Wecter, 1963).

According to the literature, people do not actually want to be their

heroes but, rather, to stand with or emulate their heroes. Moral emulation,

at any rate, is the heroic function in which the literature is interested. Some

people, however, do actually want to be their heroes. In an in-depth inter-

view, one white woman, whose hero was Princess Diana, insisted that she

actually wanted to be Princess Diana-because the interviewee wanted to

live Princess Diana's life.

220 Porpora

Finally, many people do not seem to distinguish between heroes and

ordinary role models such as their parents. People who actually want to be

their heroes may be uncommon. However, in comparison with people who

think only of cultural rather than personal heroes or who do not distinghish

between heroes and ordinary role models, people who reject the word hero

in favor of (charismatic) mentor also, probably, are relatively uncommon.

If, therefore, what we are really after is people with personal heroes

by whose moral example they attempt to live, the 40% figure is probably

a substantial overcount. While 40% may be taken as an upper bound on

people with heroes that function this way, the actual number of such people

is, likely, much lower.5

Future survey research could determine that by including some ques-

tions that ask repondents to distinguish how their heroes actually function

for them. Un-fortunately, the typology of hero functioning presented here

was developed only after the in-depth interviews were transcribed and stud-

ied, which was also after the survey was administered.

Who Are Our Heroes?

The spring survey recorded up to two heroes for each respondent

whereas the fall survey recorded up to three. In the spring, 45% of respon-

dents who named one hero also named a second. In the fall, 47% of those

who named one hero likewise named a second, and 21% named a third

as well. Between the spring and fall surveys, 162 heroes were named by

246 people. The heroes named ranged from Albert Einstein and Abraham

Lincoln to Oprah Winfrey and Oliver North.

Table II presents the types of heroes chosen by respondents. Since

many respondents named multiple heroes, there are two different units of

analysis to consider: respondents and hero mentions. Whereas in column

1 the unit of analysis is repondents, in column 3 the unit of analysis is hero

mentions. Thus, column 3 presents the number of mentions associated with

each type of hero as a percentage of total hero mentions.

Whether our unit of analysis is the individual respondent or the hero

mention, the data presented in Table II, like Smith's (1986) findings, indi-

5If anything, the biases in the data probably tend to inflate the percentage of respondents

with heroes-although only marginally. As we will see, race, age, and gender are all statis-

tically unrelated to hero identification. Since education turns out to be

positively

related to

hero identification, the overrepresentation of more educated respondents may

inflate the

percentage with heroes. Education was also positively-rather

than

negatively-related to

religiosity, but this relationship was not statistically significant. Thus, the underrepresentation

of the less educated would seem, again, not to underrepresent the very religious,

who tend

more to have heroes. If anything, the data probably overrepresent them.

Personal Heroes 221

Table II. Hero Types

Respondents Mentioning Heroes Mentions of Each Hero

of Each Type as a Percentage of Type as a Percentage of

Respondents With Heroesa Total Hero Mentions

(1)

(2) (3) (4)

Hero Types N N N N

Local 47.2 118 39.5 144

Political 28.8 72 26.0 95

Celebrities 15.6 39 14.0 51

Religious 14.0 35 10.7 39

Arts 6.4 16 4.9 18

Other 5.2 13 4.9 18

Total 100 250 100 365

aPercentages do not sum to 100% because some respondents name multiple heroes.

cate that even if Lowenthal and Boorstin are correct that our media have

replaced "true" heroes with celebrities, that does not directly manifest itself

at the level of the individual actor. In terms of mentions (column 3), ce-

lebrities account for only 14% of all heroes named. Similarly, if we take

individuals as our unit of analysis (column 1), less than 16% of respondents

with heroes cite celebrities. Finally, when we include those who have no

heroes at all, only a little over 6% of respondents identify idols of con-

sumption as heroes.

Not even comparatively do the data support the Boorstin-Lowenthal

hypothesis. Idols of consumption or celebrities are not among the most

frequently cited hero types. Instead, celebrities rank third in frequency after

local and political heroes. Among those with heroes, the number of re-

spondents who mention local heroes (47%) is about three times greater

than the number of respondents who mention celebrities (16%). Similarly,

the number of respondents who mention political heroes (29%) is almost

two times greater. Likewise, in terms of mentions, the percentage associ-

ated with celebrities (14%) lags far behind the percentages associated with

local heroes (40%) and political heroes (26%). Celebrities, in fact, do not

rank that much higher than religious heroes (11%).

Boorstin and Lowenthal are undoubtedly correct that radio, television,

and popular magazines pay undue attention to mere celebrities, crowding

out the celebration of true heroism. The media's crowding out of heroes

by celebrities may well leave people with a dearth of heroic exemplars with

whom to identify. That may explain partly why only a minority of respon-

dents say they have heroes.

On the other hand, the low frequency of celebrities identified as heroes

suggests that the public has not succumbed totally to the media bias. When

222

Porpora

we speak of whom our society identifies as heroes, therefore, we must dis-

tinguish between more or less visible aspects of culture, a distinction that

tends to coincide with the distinction between the macro and the micro.

On the one hand, the media have the power to exert a strong macrosocial

effect so that the heroes they laud will be very visible culturally. Far less

visible will be the heroes adopted by individuals, microsocially. Yet the less

visible heroes that emerge from the microsocial level are equally reflective

of who we are as a society. When the values of the micro- and macrolevels

diverge, as they evidently do in the case of heroes, it is important for ana-

lysts not to mistake the more noticeable macrolevel values as the values

of the culture tout court. Instead, alongside the more visible macrolevel

culture, there may in addition be a shadow culture at the microlevel that

goes undetected.

If at the individual level the data do not support the hypothesis derived

from Boorstin and Lowenthal's macrosocial thesis, it is because the data

overwhelmingly support the rival hypothesis derived from Taylor, who

claims that modernity tends to affirm ordinary life over any kind of tran-

scendental calling. Taylor's thesis suggests the hypothesis that individuals'

heroes will tend to be ordinary people from everyday life rather than tran-

scendental figures.

The data uphold this expectation. Local heroes-personal acquain-

tances from ordinary life-were by far the most frequent category of hero

mentioned. In fact, there were as many mentions of local heroes (40%) as

there were of the next two most frequently mentioned categories combined:

political heroes (26%) and celebrities (14%). The same pattern obtains

when the unit of analysis is respondents. Almost half of the respondents

with heroes (47%) mentioned personal acquaintances as among their he-

roes. Again, this is more than the combined number of respondents who

named either political heroes (29%) or celebrities (14%). Thus, to the ex-

tent that local heroes represent the values of ordinary life, it does appear

to be ordinary life that is affirmed by contemporary hero choice.

The contemporary affirmation of ordinary life is further indicated by

what is absent from the data: much mention of historical figures. Instead,

the data display a striking ahistoricity in hero choice. Of the 162 different

heroes mentioned, only 10 lived prior to the 20th century: Jesus, Washing-

ton, Jefferson, Lincoln, Bach, the virgin Mary, Columbus, Saint

Paul, Saint

Francis Xavier, and Socrates.6

61t might be argued that more historical heroes would have been elicited had the survey ques-

tion been worded differently, had it asked explicitly for heroes "living or dead." That may

be. On the other hand, if hero identification with a dead historical figure were truly salient

for a respondent, the question even as currently worded should have elicited it. The ahisto-

rical nature of the heroes cited in this study coincides with Greenstein's (1964) finding of a

Personal Heroes 223

While commentators (Schlesinger 1968, for example) may lament the

dearth of heroes among our contemporaries, there is no reason our heroes

must necessarily be contemporary. Indeed, if people were actively looking

for transcendental heroes, history is replete with them. All 10 of the above

historical figures, for example, represent ideals that transcend ordinary

life.

It might be said that of course people tend to choose contemporaries

as their heroes simply because it is their contemporaries with whom they

most identify. That, however, is the point: It is contemporaries we identify

with, whereas it could be otherwise. It is otherwise for those in public life

(Gardinar and Jones, 1983) and even for a small minority of the people

sampled here who are not. If people saw their lives as situated within some

kind of ongoing tradition or project as described, for example, by MacIntyre

(1981), then they likely would identify with the historical figures who sym-

bolize the traditional ideals of that project. The ahistoricity of hero iden-

tification thus may reflect what Lyotard (1984) refers to as "the end of

metanarratives," the end of any kind of transcendental narrative, whether

historical or mythical, that gives ultimate meaning to our lives.

Again, it might be that the lack of reference to historical metanarra-

tives reflects simply a contemporary lack of historical knowledge. Yet the

causal connection may well go the other way. If people saw their lives

rooted in some kind of historical metanarrative, then, presumably, historical

knowledge would follow. In that case, a contemporary lack of historical

knowledge would itself be symptomatic of a current weakness of metanar-

ratives.

Who Has Heroes?

As Table III indicates, there is not much in the data that explains

who is most likely to have heroes. No statistically significant differences

in hero identification were found between men and women, between

blacks and whites, or among people of different income or age categories.

In the analysis presented in Table IIIa, education did show a positive re-

lationship with hero identification, but that relationship failed to be sig-

nificant in the analysis presented in Table IIIb. Conversely, there was a

statistically significant relationship between self-perceived religiosity and

hero identification in the analysis presented in Table IIIb but not in that

presented in Table IIIa. The only attribute that consistently showed a sta-

decline over a 50-year period in the number of historical figures among the people that

schoolchildren say they most admire.

224 Porpora

tistically significant relationship with hero identification was concern with

transcendental meaning. That was measured by two variables: How often

one thinks about the meaning of life, and how definite one is about the

meaning of life.

How often one thinks about the ultimate meaning of human existence

was asked only in the spring survey, and thus was not included in the analy-

sis presented in Table IIIa, which encompasses the combined spring and

fall data. To this question, respondents could answer "always," "often,"

"sometimes," "rarely," or "never." 'Always" is a quite emphatic response,

which presumably affirms a life that is continuously oriented around some

ultimate meaning. This was an affirmation that was made by only 17% (n

= 47) of the respondents.

In terms of hero identification, the small minority who always think

about the meaning of life are distinct. There was no difference between

those who thought about the meaning of human existence sometimes (n

=

176) as opposed to rarely or never (n

=

46). In each case, 37% had

personal heroes. In contrast, of those who always think about the meaning

of human existence, close to 62% had heroes. Thus, in the analysis pre-

sented in Table IIIb, responses were collapsed into two categories: Those

who always think about the meaning of life and those who do not always

think about it.

In both the spring and fall surveys, respondents were asked, "Which

of the following statements best describes your attitude toward the ultimate

meaning of human existence?" Besides "Don't know," the possible re-

sponses were as follows:

(1) There is no real meaning to our existence; we are just lucky to be alive;

(2) Our existence must have some meaning, but I don't know what it is;

(3) We are here on earth for a purpose, and I feel I have some sense of what that

purpose is;

(4) We are here on earth for a purpose, and I feel I know what that purpose is;

(5) I have some other attitude toward the ultimate meaning of human existence.

In both analyses presented in Table III, the first and last responses to

this question were removed to create an ordinal scale of felt assurance

about the ultimate meaning of human existence. The 12% (n

=

73)

of

respondents who made either the first or last response express not so much

a level of certainity about the meaning of life as a repudiation of the

very

framework assumed by the question. In terms of hero identification, they

represented a distinct group.

If we leave this group aside for a moment, then it appears that the

clearer the picture one has about the meaning of life,

the more

likely

one

is to have personal heroes. Of those who think human existence

meaningful

without knowing what the meaning is (27%; n

=

161), only

a little over

Personal Heroes 225

Table III. Who is Most Likely to Have Heroes? Stepwise Multiple Regression

Analysis

A. Combined Spring and Fall Data

Independent Cummula- Cummula- Change Signific-

Variable Final p tive R tive R2

inR2

ance

Certainty about .142 .192 .037 .037 .009

meaning of lifea

Education .158 .242 .058 .022 .002

Religiosity .136 .274 .075 .016 .012

Gender .056 NA NA NA .284

Age -.088 NA NA NA .090

Income -.124 NA NA NA .124

Race .034 NA NA NA .507

B. Spring Data

Independent Cummula- Cummula- Change Signific-

Variable Final

f

tive R tive R2 in ance

Certainty about .214 .236 .056 .056 .002

meaning of life

Reflection about .197 .307 .094 .038 .005

meaning of lifeb

Religiosity .122 NA NA NA .096

Education .110 NA NA NA .120

Gender .092 NA NA NA .183

Age .005 NA NA NA .946

Income .008 NA NA NA .904

Race .046 NA NA NA .517

aOne's attitude toward the meaning of human existence (see p. 224).

bHow often one thinks about the meaning of human existence.

30% have heroes. Of those who say they have some sense of the purpose

of human existence (41%; n =

242), 42% have heroes. Finally, of the 20%

(n

=

117) who say they know what the purpose of life is-persumably, a

minority who live according to some articulated metanarrative, almost 56%

have heroes.

Returning now to those who either deny that human existence has

meaning or have some other attitude about human existence, almost 43%

have heroes, approximately the same percentage as those who have some

sense of life's meaning. Evidently, people in the anomalous category adhere

to a totally different orientation that attracts them to hero identification

more than those who are low on the more typical orienting dimension but

less than those who are high.

The statistically significant relationships between hero identification

and the two meaning variables (Table III) support Cooley's contention that

hero identification is an expression of transcendental ideals. Those more

226 Porpora

oriented toward transcendental meaning are more likely to have personal

heroes. If Taylor is correct that ours is a disenchanted age that affirms

ordinary life over transcendental meanings, these findings might also sug-

gest why the majority of respondents do not have personal heroes.

It is true that not much of the variation in hero identification is ex-

plained by the independent variables in either of the two analyses presented

in Table III. We must remember, however, that hero identification in this

study turns out to be imprecise. It excludes those who prefer the word

mentor to hero, and it includes those who actually want to be their heroes,

those who cite cultural heroes, and those who make no distinction between

heroes and ordinary role models. From the standpoint of variation ex-

plained, probably what hero identification includes is more damaging than

what it excludes. Of those who have heroes, it is only for the smaller subset

whose heroes exemplify transcendental ideals that we would expect to see

a relationship between hero identification and the two meaning variables.

Cooley explicitly tied hero identification to religiosity, itself a dimen-

sion of transcendental concern. It may seem surprising, therefore, that re-

ligiosity fails to show a signicant relationship with hero identification in the

analysis presented in Table IITb. Religiosity, however, covaries strongly with

the two meaning variables. A full third of the very religious respondents

(n = 68) say they always think about the ultimate meaning of human ex-

istence as compared with fewer than 12% (n

=

182) of those respondents

who describe themselves as other than "very religious"

(X2

=

19.948; a =

.0005). Similarly, a full 40% of the very religious respondents (n

=

121)

say they know what the meaning of life is; only 11% say life either has no

meaning or that they have some other attitude. In contrast, of those who

explicitly describe themselves as "not very religious" (n

=

152), less than

7% say they know what the meaning of life is, and close to a third (27%)

say either that life has no meaning or that they have some other attitude.

Those who describe themselves as "somewhat religious" (n

=

281) are in

between these two extremes

(X2

= 84.8; a < .001).

Examined in isolation, there is a statistically significant relationship

between religiosity and hero identification

(X2

=

14.2; a

=

.0008). Thirty-

three percent (33%) of the "not very religious" (n =

113), 38% of the

"somewhat religious" (n

=

284), and 54% of the "very religious" (n

=

153) have heroes. While in Table Illa we see that religiosity has an inde-

pendent effect on hero identication, it seems as if its stronger

effect is

indirect through the meaning variables. Indeed, when we remove either

of the two meaning variables from the analysis presented

in Table

IIlb,

religiosity again shows up as significantly related to hero identification

(,B = .128, a = .028, when attitude toward meaning

of life is

removed;

= .153, a = .035, when it is how often one thinks of the

meaning

of

Personal Heroes 227

human existence that is removed). The strongest effect of religiosity on

hero identification is, thus, in all likelihood indirect. Through religiosity,

horizons are lifted to the level of transcendental meaning, one expression

of which is hero identification.

CONCLUSION

Traditionally, heroes are the protagonists of myths-that is, meta-

phorical or figurative accounts that are addressed to the ultimate ques-

tions: Who are we? Where did we come from? Why are we here?

Addressed to ultimate questions as they are, myths relate to a sacred plane

of existence, a plane that transcends profane, everyday life. In the sacred

plane, heroes personify transcendent ideals and transcendent visions of

the good.

It often has been argued that ours is a largely demythologized, profane

culture, where people generally do not orient their lives meaningfully

around mythic paradigms or transcendental metanarratives. The data pre-

sented here lend support to that view. According to the data, few people

seem to think intensely about the meaning of human existence in general,

and, accordingly, few seem to conform confidently to any kind of articu-

lated, grand metanarrative.

Taylor argues that it is everyday life that is valorized now, not some

higher plane of transcendent purpose. Ours, he says, is instead a bourgeois

culture, where the good is found in the ordinary acts of work, home, and

leisure. Without a transcendent plane in which we are required to orient

ourselves, we may feel little cultural need for personal heroes. As the

mythic dwelling place of heroes is culturally marginal, perhaps its heroic

residents are marginal as well.

Again, the data seem to support this view. Most people do not have

personal heroes, and among those who do, most frequently cited are the

local heroes of ordinary life. It is likely no accident, furthermore, that peo-

ple with personal heroes tend to be both religious and attuned to grand

metanarratives. If in its most vibrant form, heroes relate to ultimate con-

cerns, then it will be those who are consciously directed to such concerns

who will be most likely to have heroes. Heroes and heroic callings have so

far received little mention in the literature on desacralization. Yet like ritu-

als, prayer, and attendence at religious services, they are important dimen-

sions of the sacredly engaged life. Hopefully, this paper will stimulate

further attention to this topic.

228 Porpora

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the following people for their helpful comments

on previous drafts of this paper: Orly Benjamin, Hugo Freund, Ernest

Hakanen, William Rosenberg, William Sullivan, and Alan Wolfe. I would

also like to express my appreciation to the anonymous referees who helped

make this a better paper.

REFERENCES

Balswick, Jack

1982 "Heroes and heroines among Ameri-

can adolescents." Sex Roles 8:243-249.

Becker, Ernest

1973 The Denial of Death. New York: Free

Press.

Beiting, Ralph W.

1994 Frontier of the Heart: The Search for

Heroes in Appalachia. Lancaster, KY:

Christian Appalachian Project.

Bell, Elizabeth

1983 "The cultural roots of our current in-

fatuation with television's befuddled

hero." In Ray B. Browne and Marshall

Fishwick (eds.), The Hero in Transi-

tion: 188-194. Bowling Green, OH:

Bowling Green University Press.

Boorstin, Daniel

1968 "From hero to celebrity: The human

pseudo-event." In Harold Lubin (ed.),

Heroes and Anti-Heroes: A Reader in

Depth: 325-340. Scranton, PA: Chan-

dler.

Campbell, Joseph

1968 The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Carlyle, Thomas

1895 On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the

Heroic in History. London: Chapman

and Hall.

Cooley, Charles Horton

1964 Human Nature and the Social Order.

New York: Schocken.

Eliade, Mircea

1959 The Sacred and the Profane. New

York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo

1940 "Heroism." In Brooks Atkinson (ed.),

The Complete Essays and Other Writ-

ings of Ralph Waldo Emerson: 249-

260. New York: Random House.

Fishwick, Marshall

1983 "Introduction." In Ray B. Browne and

Marshall Fishwick (eds.) The Hero in

Transition: 5-14. Bowling Green, OH:

Bowling Green University Press.

Gardiner, John, and Katryn E. Jones

1983 "Leaders of the American West: Who

are their heroes?" In Ray B. Browne

and Marshall Fishwick (eds.), The

Hero in Transition: 285-294. Bowling

Green, OH: Bowling Green University

Press.

Glicksberg, Charles I.

1968 "The tragic hero." In Harold Lubin

(ed.), Heroes and Anti-Heroes: A

Reader in Depth: 356-366. Scranton,

PA: Chandler.

Greenstein, Fred

1964 "New light on American values: A for-

gotten body of survey data." Social

Forces 42: 441-450.

Hakanen, Ernest

1989a Adolescent Identification of Heroes:

A Study of Media Exposure and Per-

ception of Public Figures. Unpublished

Ph.D. dissertation, Temple University.

1989b "The (d)evolution of heroes: An ex-

panded typology of heroes for the

electronic age." Free Inquiry in Crea-

tive Sociology 17:153-158.

Hook, Sidney

1943 The Hero in History: A Study in Limi-

tation and Possibility. Boston: Beacon.

Hubbard, Rita

1983 "The changing-unchanging heroines

and Heroes of Harlequin Romances

1950-1979." In Ray B. Browne and

Marshall Fishwick (eds.), The Hero in

Personal Heroes 229

Transition: 171-179. Bowling Green,

OH: Bowling Green University Press.

Keen, Sam

1994 Hymns to an Unknown God. New

York: Bantam.

Lyotard, Jean-Francois

1984 The Postmodern Condition: A Report

on Knowledge. Minneapolis: Univer-

sity of Minnesota Press.

Lowenthal, Leo

1943 "Biographies in popular magazines."

In P. Lazersfeld and F Stanton (eds.),

Radio Research: 507-543. New York:

Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

Lubin, Harold

1968 "Why Heroes?" In Harold Lubin

(ed.), Heroes and Anti-Heroes: A

Reader in Depth: 3-6. Scranton, PA:

Chandler.

Maclntyre, Alasdair

1981 After Virtue. Notre Dame, IN: Uni-

versity of Notre Dame.

Miller, Mark Crispin

1986 "Deride and conquer." In Todd Gitlin

(ed.), Watching Television: 183-228.

New York: Pantheon.

Patterson, James and Peter Kim

1991 The Day America Told the Truth:

What People Really Believe about

Everything that Matters. New York:

Prentice-Hall.

Rickman, Peter

1983 "Quixote rides again: The popularity

of the thriller" In Ray B. Browne and

Marshall Fishwick (eds.) The Hero in

Transition. Bowling Green, OH: Bowl-

ing Green University Press.

Rollin, Roger

1983 "The Lone Ranger and Lenny Skut-

nic: The hero as popular culture." In

Ray B. Browne and Marshall Fishwick

(eds.), The Hero in Transition: 14-45.

Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green

University Press.

Schlesinger, Arthur, Jr.

1968 "The decline of heroes." In Harold

Lubin (ed.), Heroes and Anti-Heroes:

A Reader in Depth: 348-351. Scran-

ton, PA: Chandler.

Schwartz, Barry

1985 "Emerson, Cooley, and the American

heroic vision." Symbolic Interaction 8:

103-120.

Smith, Tom W.

1986 "The polls: The most admired man

and woman." Public Opinion Quar-

terly 50: 573-583.

Spethmann, Betsy

1991 "Cautious consumers have surveyers

wary." Advertising Age. June 10: 34.

Taylor, Charles

1989 Sources of the Self. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Tillich, Paul

1952 The Courage to Be. New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press.

Warner, William Lloyd

1959 The Living and the Dead: A Study of

the Symbolic Life of Americans. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Weber, Max

1947 The Theory of Social and Economic

Organization. New York: The Free

Press.

Wecter, Dixon

1963 The Hero in America: A Chronicle of

Hero-Worship. Ann Arbor: University

of Michigan.

You might also like

- How To Go Out of Your MindDocument80 pagesHow To Go Out of Your MindJuan DavidNo ratings yet

- Ancient Greek PDFDocument97 pagesAncient Greek PDFartemida_92% (13)

- Ancient Greek PDFDocument97 pagesAncient Greek PDFartemida_92% (13)

- Case Analysis and ExhibitsDocument158 pagesCase Analysis and ExhibitsOwel Talatala100% (1)

- The Occult Tarot and MythologyDocument44 pagesThe Occult Tarot and MythologyChuck RutherfordNo ratings yet

- 3 Solve Address Routine ProblemsDocument31 pages3 Solve Address Routine ProblemsEsperanza TayaoNo ratings yet

- Counseling IDocument44 pagesCounseling IHemant Prasad100% (1)

- Van Caenegem - An Historical Introduction To Private Law PDFDocument224 pagesVan Caenegem - An Historical Introduction To Private Law PDFСергей Бизюков0% (1)

- (9783110299557 - Initiation Into The Mysteries of The Ancient World) v. The Mysteries of Isis and MithrasDocument32 pages(9783110299557 - Initiation Into The Mysteries of The Ancient World) v. The Mysteries of Isis and Mithrasartemida_No ratings yet

- When God Spoke GreekDocument18 pagesWhen God Spoke Greekartemida_100% (1)

- Athletics and Social Order in SpartaDocument66 pagesAthletics and Social Order in Spartaartemida_No ratings yet

- Athletics and Social Order in SpartaDocument66 pagesAthletics and Social Order in Spartaartemida_No ratings yet

- Phenomenology of FameDocument34 pagesPhenomenology of FameSmeden Nordkraft100% (1)

- Λεξικό Αρχαίας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας PDFDocument310 pagesΛεξικό Αρχαίας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας PDFartemida_No ratings yet

- Introducing Narrative PsychologyDocument14 pagesIntroducing Narrative Psychologydreamer44No ratings yet

- Being A Celebrity: A Phenomenology of Fame - Donna Rockwell David C. GilesDocument33 pagesBeing A Celebrity: A Phenomenology of Fame - Donna Rockwell David C. GilesZovem Se Hristina0% (1)

- Student Teaching ReflectionDocument1 pageStudent Teaching Reflectionalihanson86No ratings yet

- LEXIKON Mon Hornblower Elaine Matthews Greek Personal NAMES 2001 PDFDocument193 pagesLEXIKON Mon Hornblower Elaine Matthews Greek Personal NAMES 2001 PDFartemida_100% (1)

- LEXIKON Mon Hornblower Elaine Matthews Greek Personal NAMES 2001 PDFDocument193 pagesLEXIKON Mon Hornblower Elaine Matthews Greek Personal NAMES 2001 PDFartemida_100% (1)

- Transgenerational Transmissions and Chosen TraumaDocument24 pagesTransgenerational Transmissions and Chosen TraumaCarlos DevotoNo ratings yet

- Lambert, S. (2012) - Inscribed Athenian Laws and Decrees 352:1-322:1 BCDocument447 pagesLambert, S. (2012) - Inscribed Athenian Laws and Decrees 352:1-322:1 BCartemida_No ratings yet

- American Tricksters: Thoughts on the Shadow Side of a Culture's PsycheFrom EverandAmerican Tricksters: Thoughts on the Shadow Side of a Culture's PsycheNo ratings yet

- CAP719 Fundamentals of Human FactorsDocument38 pagesCAP719 Fundamentals of Human Factorsbelen1110No ratings yet

- Title of The Module Chapter 10: Jose Rizal and Philippine NationalismDocument11 pagesTitle of The Module Chapter 10: Jose Rizal and Philippine NationalismJerico Ubaldo50% (2)

- Malignant Narcissism, Rage & LRon HubbardDocument52 pagesMalignant Narcissism, Rage & LRon HubbardnyrelicsNo ratings yet

- Personal Heroes, Religion, and Transcendental MetanarrativesDocument22 pagesPersonal Heroes, Religion, and Transcendental MetanarrativesvolodeaTisNo ratings yet

- A Reflection by Daniel CoDocument8 pagesA Reflection by Daniel CoDaniel Vincent CoNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibiliographyDocument6 pagesAnnotated BibiliographyStudy AssistantNo ratings yet

- Heroism: A Conceptual Analysis and Differentiation Between Heroic Action and Altruism - Franco, Blau & Zimbardo 2011Document15 pagesHeroism: A Conceptual Analysis and Differentiation Between Heroic Action and Altruism - Franco, Blau & Zimbardo 2011Zeno FrancoNo ratings yet

- The Hero's Journey - Tracing The History of The Myth To The CelebrityDocument72 pagesThe Hero's Journey - Tracing The History of The Myth To The CelebrityAlonsoPahuachoPortellaNo ratings yet

- Title of The Module 10: Jose Rizal and Philippine Nationalism: Bayani at KabayanihanDocument21 pagesTitle of The Module 10: Jose Rizal and Philippine Nationalism: Bayani at KabayanihanDarlyn MauricioNo ratings yet

- Configuring America: Iconic Figures, Visuality, and the American IdentityFrom EverandConfiguring America: Iconic Figures, Visuality, and the American IdentityKlaus RieserNo ratings yet

- Igou 2015 ZeroingDocument58 pagesIgou 2015 ZeroingRafi AddinNo ratings yet

- How Can We Study HeroismDocument15 pagesHow Can We Study Heroismmiguel6789No ratings yet

- Rogersetal JPSP InPress ManuscriptPrepublicationDocument87 pagesRogersetal JPSP InPress ManuscriptPrepublicationApy BobbyNo ratings yet

- Genre Analysis and Intertextualtiy Final Draft 1Document7 pagesGenre Analysis and Intertextualtiy Final Draft 1api-665546996No ratings yet

- The Humanity of HeroesDocument4 pagesThe Humanity of Heroest88qdvg894No ratings yet

- QueerTheoryChapter RiggsTreharneDocument33 pagesQueerTheoryChapter RiggsTreharnePrasansa SaikiaNo ratings yet

- What Makes a Person a PersonDocument4 pagesWhat Makes a Person a PersonNjono SlametNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2: Criteria For A Hero: Life and Works of RizalDocument5 pagesLesson 2: Criteria For A Hero: Life and Works of RizalJuvy YabutNo ratings yet

- Essay About HeroDocument6 pagesEssay About Herod3hfdvxm100% (2)

- Rough DraftDocument11 pagesRough Draftapi-282139127No ratings yet

- When Organizational Members Come Face To Face With The Supreme LeaderDocument28 pagesWhen Organizational Members Come Face To Face With The Supreme LeaderTejaRejcNo ratings yet

- Queer Theory: April 2017Document33 pagesQueer Theory: April 2017VasaviNo ratings yet

- Hale, EthnictyDocument28 pagesHale, Ethnictymada_rxyNo ratings yet

- Heroes Thesis StatementDocument5 pagesHeroes Thesis Statementelizabethtemburubellevue100% (2)

- Celebrity Culture: Bibliographic ReviewDocument9 pagesCelebrity Culture: Bibliographic ReviewEssa Piez FernandezNo ratings yet

- ExpsyDocument43 pagesExpsykringkytNo ratings yet

- 1887 - 3180830 Fernandez ArmestoDocument13 pages1887 - 3180830 Fernandez Armestoerenyeagerattacktitan799No ratings yet

- Harry Potter and The Measures of Personality ExtraDocument7 pagesHarry Potter and The Measures of Personality ExtraMarco Salva PazNo ratings yet

- Thornborrow, T. & Brown, A.D. 2009. Being Regimented': Aspiration, Discipline and Identity Work in The British Parachute RegimentDocument38 pagesThornborrow, T. & Brown, A.D. 2009. Being Regimented': Aspiration, Discipline and Identity Work in The British Parachute Regimentalje coolmusicNo ratings yet

- American Hero-MythsDocument120 pagesAmerican Hero-MythsGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- FUNCION DE LOS MITOSLeiradeCarvalho2018Document15 pagesFUNCION DE LOS MITOSLeiradeCarvalho2018Axel Uziel Arias DietrichNo ratings yet

- Naming A New Self: Identity Elasticity and Self-Definition in Voluntary Name ChangesDocument11 pagesNaming A New Self: Identity Elasticity and Self-Definition in Voluntary Name ChangesakshayppNo ratings yet

- The Call of The Wild EssayDocument3 pagesThe Call of The Wild Essayafibafftauhxeh100% (2)

- Jesus and his Cast of ArchetypesDocument22 pagesJesus and his Cast of Archetypesbuster301168No ratings yet

- Essays On Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument6 pagesEssays On Corporate Social Responsibilityvdyvfjnbf100% (2)

- Tomas BogardusDocument20 pagesTomas BogardusSperanzaNo ratings yet

- Personality and Social Psychology BulletinDocument14 pagesPersonality and Social Psychology BulletinPersephona13No ratings yet

- Cheng 1Document17 pagesCheng 1Perijoresis BertoliniNo ratings yet

- Com Modification of SelfDocument9 pagesCom Modification of SelfSpeckled JimNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 11 577862Document13 pagesFpsyg 11 577862Marcus Antonino McGintyNo ratings yet

- Life and Works of Rizal DOCSDocument6 pagesLife and Works of Rizal DOCSFaye Garnet PiamonteNo ratings yet

- Durkheim and Weber: Understanding Celebrity: Maggie Carragher SOAN 330 FinalDocument17 pagesDurkheim and Weber: Understanding Celebrity: Maggie Carragher SOAN 330 Finalapi-309773645No ratings yet

- Kelly ThesisDocument15 pagesKelly ThesisSheila Sinclair100% (2)

- Final Paper - Comm Theory Patterson 1Document10 pagesFinal Paper - Comm Theory Patterson 1api-547450934No ratings yet

- Defining and Surveying Heroism by Michael "Xiao" Chua, January 20, 2018Document5 pagesDefining and Surveying Heroism by Michael "Xiao" Chua, January 20, 2018the architographerNo ratings yet

- Module 1 JOSE RIZAL 1Document5 pagesModule 1 JOSE RIZAL 1Zosimo RivasNo ratings yet

- Fiske, Xu & Cuddy (1999) (Dis) Respecting Versus (Dis) Liking JSIDocument17 pagesFiske, Xu & Cuddy (1999) (Dis) Respecting Versus (Dis) Liking JSISimone AraujoNo ratings yet

- The Function of Character Archetype For Adventure Formula in The Hero's Journey in The Novel of Rick Riordan's The Lost Hero 2010Document25 pagesThe Function of Character Archetype For Adventure Formula in The Hero's Journey in The Novel of Rick Riordan's The Lost Hero 2010AlbiNo ratings yet

- Erik Ringmar, International Politics of RecognitionDocument23 pagesErik Ringmar, International Politics of RecognitionErik Ringmar100% (1)

- Running Head: The Necessary Removal 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: The Necessary Removal 1Muhammad Bilal AfzalNo ratings yet

- Artigo Driessens CelebridadeDocument30 pagesArtigo Driessens CelebridadeCallipoNo ratings yet

- IdentityDocument6 pagesIdentityChristina HernandezNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Athenian CitizenshipDocument10 pagesRethinking Athenian Citizenshipartemida_No ratings yet

- Chasing Shadows Lives of Ancient Greek Statues As Lived by WritersDocument13 pagesChasing Shadows Lives of Ancient Greek Statues As Lived by Writersartemida_No ratings yet

- Epigraphy in Early Modern Greece: Nikolaos PapazarkadasDocument14 pagesEpigraphy in Early Modern Greece: Nikolaos Papazarkadasartemida_No ratings yet

- Naiden's Review of Book PDFDocument4 pagesNaiden's Review of Book PDFartemida_No ratings yet

- Parvum LexiconDocument220 pagesParvum Lexiconartemida_No ratings yet

- Kessling Melting Down StatuesDocument25 pagesKessling Melting Down Statuesartemida_No ratings yet

- The Experiential Qualities of Thucydides' NarrativeDocument28 pagesThe Experiential Qualities of Thucydides' Narrativeartemida_No ratings yet

- Michael - Squire - Embodying - The - Dead - On - Classical Gravestones PDFDocument28 pagesMichael - Squire - Embodying - The - Dead - On - Classical Gravestones PDFartemida_No ratings yet

- Foxhall (2013) ReligionDocument21 pagesFoxhall (2013) Religionartemida_No ratings yet

- Moralism' in HistoriographyDocument41 pagesMoralism' in Historiographyartemida_No ratings yet

- The Greek Alphabet-Class NotesDocument2 pagesThe Greek Alphabet-Class Notesartemida_No ratings yet

- Melfi (2010) - Asklepieia of Roman Greece PDFDocument23 pagesMelfi (2010) - Asklepieia of Roman Greece PDFartemida_No ratings yet

- Melfi (2010) - Asklepieia of Roman Greece PDFDocument23 pagesMelfi (2010) - Asklepieia of Roman Greece PDFartemida_No ratings yet

- Bremmer MythandRitual4Document23 pagesBremmer MythandRitual4artemida_No ratings yet

- Eumolpos Eleusis PDFDocument25 pagesEumolpos Eleusis PDFartemida_No ratings yet

- Cockfights and Contradictions in Ancient Greek CultureDocument33 pagesCockfights and Contradictions in Ancient Greek Cultureartemida_No ratings yet

- Bremmer MythandRitual4 PDFDocument23 pagesBremmer MythandRitual4 PDFartemida_100% (1)

- Madness in Herodotus PDFDocument329 pagesMadness in Herodotus PDFartemida_No ratings yet

- Lupu (2003)Document20 pagesLupu (2003)artemida_No ratings yet

- Why Not Paint An Altar A Study of Where PDFDocument28 pagesWhy Not Paint An Altar A Study of Where PDFartemida_No ratings yet

- De Elderly Retirement Homes InPH Ver2 With CommentsDocument20 pagesDe Elderly Retirement Homes InPH Ver2 With CommentsgkzunigaNo ratings yet

- Glenwood High School Elite Academic Academy Cambridge Private Candidate Registration Form-2019Document1 pageGlenwood High School Elite Academic Academy Cambridge Private Candidate Registration Form-2019RiaanPretoriusNo ratings yet

- Syllabus - Middle School WritingDocument11 pagesSyllabus - Middle School Writingmrspercuoco100% (2)

- I Day SpeechDocument2 pagesI Day SpeechRitik RajNo ratings yet

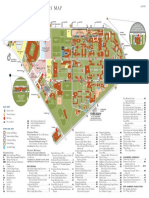

- Rice University Campus Map GuideDocument1 pageRice University Campus Map GuideUthaya ChandranNo ratings yet

- Confirmation BiasDocument6 pagesConfirmation Biaskolli.99995891No ratings yet

- Aiden Tenhove - ResumeDocument1 pageAiden Tenhove - Resumeapi-529717473No ratings yet

- Music8 - q2 - W3&4fillable - Ma - Luz AmaroDocument9 pagesMusic8 - q2 - W3&4fillable - Ma - Luz AmaroGennrick PajaronNo ratings yet

- Popular Versus Scholarly Sources WorksheetDocument6 pagesPopular Versus Scholarly Sources WorksheetTanya AlkhaliqNo ratings yet

- English Requirements Alfabet Wageningen 2014Document1 pageEnglish Requirements Alfabet Wageningen 2014RIZKANo ratings yet

- Rules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No 9208 - Anti-Trafficking ActDocument18 pagesRules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No 9208 - Anti-Trafficking ActSui100% (2)

- Intro To Poetry Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesIntro To Poetry Lesson Planapi-383537126No ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility-27AprDocument23 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility-27AprDeepu JoseNo ratings yet

- 2018 Annual Report - Legal Council For Health JusticeDocument30 pages2018 Annual Report - Legal Council For Health JusticeLegal CouncilNo ratings yet