Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evans On Empirical Aspects of 2-Sided Markets

Uploaded by

Jorge Gonza0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views19 pagesMulti-sided platform markets have two or more different groups of customers. Businesses devise pricing, product, and other competitive strategies to keep multiple customer groups on a common platform. Multi-sided platforms coordinate the demand of distinct groups of customers who need each other in some way.

Original Description:

Original Title

Evans on Empirical Aspects of 2-Sided Markets

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMulti-sided platform markets have two or more different groups of customers. Businesses devise pricing, product, and other competitive strategies to keep multiple customer groups on a common platform. Multi-sided platforms coordinate the demand of distinct groups of customers who need each other in some way.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views19 pagesEvans On Empirical Aspects of 2-Sided Markets

Uploaded by

Jorge GonzaMulti-sided platform markets have two or more different groups of customers. Businesses devise pricing, product, and other competitive strategies to keep multiple customer groups on a common platform. Multi-sided platforms coordinate the demand of distinct groups of customers who need each other in some way.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 19

Review of Network Economics Vol.

2, Issue 3 September 2003

191

Some Empirical Aspects of Multi-sided Platform Industries

DAVID S. EVANS*

NERA Economic Consulting

Abstract

Multi-sided platform markets have two or more different groups of customers that businesses have to get

and keep on board to succeed. These industries range from dating clubs (men and women), to video game

consoles (game developers and users), to payment cards (cardholders and merchants), to operating system

software (application developers and users). They include some of the most important industries in the

economy. A survey of businesses in these industries shows that multi-sided platform businesses devise

entry strategies to get multiple sides of the market on board and devise pricing, product, and other

competitive strategies to keep multiple customer groups on a common platform that internalizes

externalities across members of these groups.

1 Introduction

Multi-sided platforms coordinate the demand of distinct groups of customers who need each

other in some way. Dating clubs, for example, enable men and women to meet each other;

yellow pages provide a way for buyers and sellers to find each other; and computer operating

system vendors provide software that applications users, applications developers, and hardware

providers can use together. When devising pricing and investment strategies, multi-sided

platforms must account for interactions between the demands of multiple groups of customers. In

theory, the optimal price to customers on one side of the platform is not based on a markup

formula such as that given by the Lerner condition, and price does not track marginal cost.

Competition among platforms takes place when seemingly distinct customer groups are

connected through interdependent demand and a platform that, acting as an intermediary,

internalizes the resulting indirect network externalities (Rochet and Tirole, 2003). Platforms are

central to many key industries including computer games, information technology, many

internet-based industries, media, mobile telephony and other telecommunications industries, and

payment systems.

* David S. Evans. Senior Vice President. NERA Economic Consulting, 1 Main Street, Cambridge, MA, 02142.

Email: David.Evans@NERA.com The author is extremely grateful to Howard Chang, Richard Bergin, Lauri

Mancinelli, John Scalf, Nese Nasif, and Bernard Reddy for their many contributions to the research upon which

article is based. This paper draws material from The Antitrust Economics of Two-Sided Markets available at

http://aei.brookings.org/admin/pdffiles/phpMt.pdf.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

192

This article provides an empirical survey of entry, pricing and other strategies in platform

industries. It provides background for the emerging theoretical (Rochet and Tirole, 2003; Julien,

2001; Armstrong, 2002; and Parker and Van Alstyne, 2002); empirical (Rysman, 2002), and

policy (Evans, 2003) literature on multi-sided platform markets. Although it does not provide

empirical tests of either the key assumptions of this literature or its implications, it confirms that

multi-sided platforms are an important, and until recently unrecognized, part of the industrial

organization landscape, and that this new area of economic research has potentially rich

empirical implications and relevance. This article is based, and reports early results, of a series of

detailed case studies of multi-sided platform industries I have been conducting.

Section 2 summarizes the conditions under which a multi-sided platform may emerge and the

main theoretical findings of the literature to date. It also provides a brief overview of the three

major kinds of platforms. Section 3 reviews some common business practices followed in multi-

sided platform industries studied thus far. I then turn to two more detailed case studies. Section 4

reviews the entry of Diners Club in the payment card industry and summarizes the pricing

strategies that continue to this day. Section 5 examines the entry of the Palm operating system

for personal digital assistants. Section 6 makes some brief concluding remarks.

2 A brief review of the economics of multi-sided platform markets

There is an opportunity for a platform to increase social surplus when three necessary conditions

are true: (1) there are distinct groups of customers; (2) a member of one group benefits from

having his demand coordinated with one or more members of another group; and (3) an

intermediary can facilitate that coordination more efficiently than bi-lateral relationships

between the members of the group.

1

As an empirical matter, indirect network effects generally

accompany condition (2) and intimately shape the business strategies in these industries along

side the multi-sidedness.

(1) There are two or more distinct groups of customers. These customers may be quite different

from each other, such as the men and women for a dating platform or retailers and

customers for a shopping mall. Alternatively, these customers may be different only for the

purpose of the transaction at hand eBay users are sometimes buyers, sometimes sellers;

mobile phone users are sometimes callers, sometimes receivers.

(2) There are externalities associated with customers A and B becoming connected or

coordinated in some fashion. A cardholder benefits when a merchant takes his card for

payment; a merchant benefits when a cardholder has a form of payment he takes. The

presence of indirect network effects seems to be an empirically important explanation for

the emergence of a platform although not necessary as a matter of theory. Sellers of PEZ

dispensers value exchanges that have more people who would like to buy PEZ dispensers.

(See discussion of eBay below.)

(3) An intermediary can internalize the externalities created by one group for the other group.

Obviously, if the members of group A and group B could enter into bilateral transactions

1

See Rochet and Tirole (2002), Rochet and Tirole (2003), Rochet (2003), Armstrong (2002), and Parker and Van

Alstyne (2002).

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

193

they would be able to internalize the indirect externalities under the second condition (2).

However, in practice information and transaction costs and free-riding problems make it

difficult for members of distinct customer groups to internalize the externalities on their

own.

2

You can look for your new sweetheart by strolling around the Boston Public Garden;

the Yahoo! Personals are less romantic but perhaps more efficient. The intermediary does

not have to be a business in the usual sense. Cooperatives have emerged in payment cards

(Visa International) and software (Linux). Governments sometimes act as the intermediary

currency is an example.

Several articles have examined the economics of price determination in multi-sided platform

markets. A key finding is that optimal prices for the multiple customer groups must align or

balance the demand among these groups and indeed the emergence of a pricing structure as

well as a pricing level is the defining characteristic of such industries (Rochet and Tirole, 2002).

Optimal prices are not proportional to marginal costs as is the case with the familiar Lerner

conditions

3

or its multi-product variants.

4

Indeed, it is possible that the optimal price for one side

will be less than the marginal cost for that side (Parker and Van Alstyne, 2002). (The assignment

of costs to one side or another may not be well defined either. When it is necessary to get both

sides together for a platform product to exist that is for either customer to have anything to

purchase one may not be able to say that one side or another caused a cost.) Platform

businesses may tend to skew prices towards one side or another depending upon the magnitude

of the indirect network externalities resulting from that side. If side A generates a much greater

degree of externalities for side B than side B does for side A, side A may tend to get a lower

price (Parker and Van Alstyne, 2002). As in Ramsey-type models of multi-product pricing, in

which firms are pricing in part to recover common costs of production, one side may end up

contributing more to common costs than another side. However, the economic reasons for this

are different in multi-sided than in single-sided markets.

5

Note that the theoretical literature is

based on quite rarefied assumptions and has thus far focused on static pricing issues.

The remainder of this article examines several multi-sided platform industries. It is helpful to

divide multi-sided platforms into three categories: (1) market-makers; (2) audience-makers; and

(3) demand coordinators. Table 1 provides further examples of multi-sided platform markets and

businesses that participate in these markets. While by no means exhaustive, it illustrates the

variety of multi-sided platform industries.

Market-makers enable members of distinct groups to transact with each other. Each member

of a group values the service more highly if there are more members of the other group

because that increases the likelihood of a match and reduces the time it takes to find an

acceptable match. Examples include exchanges such as NASDAQ and eBay, shopping malls

such as those that dot the New Jersey Turnpike, and dating services such as Yahoo! Personals.

6

2

In unpublished work Jean Tirole points out that a necessary condition for multi-sided platforms to arise is that the

Coase Theorem does not apply.

3

The Lerner condition was first stated in Lerner (1934).

4

See generally Baumol, Panzar and Willig (1982).

5

See generally Rochet and Tirole (2003), and Parker and Van Alstyne (2002).

6

See NASDAQ (2003) Market Characteristics http://www.nasdaq.com/about/market_characteristics.pdf, eBay

Inc. (2003) Company Overview, http://pages.ebay.com/community/aboutebay/overview/index.html, Pashigian

and Gould (1998), and Yahoo! Inc. (2003) Yahoo! Personals, http://personals.yahoo.com/.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

194

Industry Two-Sided Platform Category Side One Side Two

Side that Gets

Charged Least Sources of Revenue

Real Estate Residential

Property Brokerage

Market-

makers

Buyer Seller Side One Real estate brokers derive income principally

from sales commissions.

a

Real Estate Apartment

Brokerage

Market-

makers

Renter Owner/

Landlord

Typically Side One Apartment consultants and locater services

generally receive all of their revenue from the

apartment lessors once they have successfully

found tenants for the landlord.

b

Media Newspapers and

Magazines

Audience

makers

Reader Advertiser Side One Approximately 80 percent of newspaper revenue

comes from advertisers.

c

Media Network Television Audience

makers

Viewer Advertiser Side One For example, the FOX television network earns

its revenues primarily from advertisers.

d

Media Portals and Web

Pages

Audience

makers

Web

Surfer

Advertiser Side One For example, Yahoo! earns 75 percent of its

revenues from advertising.

e

Software Operating System Demand

coordinators

Applicatio

n User

Application

Developer

Side Two For example, Microsoft earns at least 67 percent

of its revenues from licensing packaged

software to end-users.

f

Software Video Game

Console

Demand

coordinators

Game

Player

Game

Developer

Neither Both sides

are significant

sources of platform

revenue

Both game sales to end users and licensing to

third party developers are significant sources of

revenue for console manufacturers. Console

manufacturers have sold their video game

consoles near or below marginal cost (not taking

into account research and development).

Microsoft, for instance, is selling its Xbox for at

least $125 below marginal cost.

g

Payment

Card System

Credit Card Demand

coordinators

Cardholder Merchant Side One For example, in 2001, American Express earned

82 percent of its revenues from merchants,

excluding finance charge revenue.

h

Table 1: Sources of revenue in selected two-sided platforms

Notes:

a

See Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor (2003) Real Estate Brokers and Sales Agents, in Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2002-03 Edition,

362-364, http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos120.htm.

b

See Ronan (1998).

c

See George and Waldfogel (2000).

d

See FOX (2000) Annual Report.

e

See Yahoo! Inc. (2001)

Annual Report.

f

See IDC (1994) 1994 Worldwide Software Review and Forecast, Report #9358, November, IDC (1995) 1995 Worldwide Software Review and

Forecast, Report # 10460, November, IDC (1996) 1996 Worldwide Software Review and Forecast, Report #12408, November, IDC (1997) 1997 Worldwide Software

Review and Forecast, Report #14327, October, IDC (1999) 1999 Worldwide Software Review and Forecast, Report #20161, October, IDC (2001) Worldwide Software

Market Forecast Summary, 2001-2005, Report #25569, September.

g

See Becker (2000), Fahey (2002).

h

See American Express Company (2001) Annual Report,

http://www.onlineproxy.com/amex/2002/ar/pdf/axp_ar_2001.pdf.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

195

Audience-makers match advertisers to audiences. Advertisers value the service more if there

are more members of an audience who will react positively to their messages; audiences value

the service more if there are more useful messages (Goettler, 1999). Advertising-supported

media such as magazines, newspapers, free television, yellow pages, and many Internet portals

are audience makers.

7

Demand-coordinators make goods and services that generate indirect network effects across

two or more groups. They are a residual category but economically the most interesting and the

least studied. These platforms do not strictly sell transactions like a market maker or

messages like an audience-maker. Software platforms such as Windows and the Palm OS,

payment systems such as debit cards, and mobile telephones are examples (Rochet and Tirole,

2003).

8

3 Business models in multi-sided platform markets

Several issues occur repeatedly in multi-sided platform markets: getting both sides on board;

balancing interests; multihoming; scaling and liquidity.

3.1 Getting both sides on board

An important characteristic of two-sided markets is that the demand on each side tends to vanish

if there is no demand on the other regardless of what the price is. There are many references in

the literature on the firms discussed earlier about solving the chicken-and-egg problem (Gawer

and Cusumano, 2002). For example, there would be no demand by households for payment cards

if they could not use them anywhere and no demand by retailers for payment cards if no one had

them. Which comes first the cardholder or the retailer (Evans and Schmalensee, 1999)? Men

will not go to dating clubs that women do not attend because they cannot get a date. Merchants

will not take a payment card if no customer carries it because no transaction will materialize.

Computer users will not use an operating system that does not have applications they need to

run. Sellers of corporate bonds will not use a trading mechanism that does not have any buyers.

In all these cases, the businesses that participate in these industries have to figure out ways to get

both sides on board. Investment and pricing strategies are keys to getting both sides on board.

One way to do this is to obtain a critical mass of users on one side of the market by giving

them the service for free or even paying them to take it. Especially at the entry phase of firms in

multi-sided markets, it is not surprising to see precisely this strategy. Diners Club gave its charge

card away to cardholders at first there was no annual fee and users got the benefit of the float.

Netscape gave away its browser to most users to get a critical mass on the computer user side of

the market; after Microsoft started giving away its browser to all users, Netscape followed suit

7

In a fundamental sense, what advertisers demand, and what the various advertising media outlets supply, are units

of audience for advertising messages. Thus advertiser demand for space in the print media and time in the broadcast

media is a derived demand stemming from a demand for audience, and is a positive function of the size and quality

of audience (Ferguson, 1983).

8

Mobile telephone services are not a one-sided market because most users both make and receive calls. A high

termination charge raises the marginal cost of calls and lowers the marginal cost of call receptions. For a given call,

end users are on a single side and their consumption behaviors depend on their own price (calling price for the caller

and receiving price for the receiver). As a consequence, the choice of termination charge is not neutral. See Jeon, et

al. (2001) for more detail.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

196

(Wong, 1998). Microsoft is reportedly subsidizing the sales of its Xbox hardware to consumers

to get them on board (Becker, 2002). For monopoly and duopoly cases, if there is sufficient

difference in the valuation of a transaction then the market with low valuation will be flooded in

equilibrium and that type will pay zero price according to some recent theoretical work (Schiff,

2003).

Another way to solve the chicken-and-egg problem is to invest in one side of the market to

lower the costs to consumers on that side of participating in the market. Microsoft provides a

good example of this. As we saw earlier, it invests in applications writers by developing tools

that help them write applications and providing other assistance that makes it easier for

developers to write applications using Microsoft operating systems. To take another example,

bond dealers take positions in their personal accounts for certain bonds they trade. They do this

when the bond is thinly traded and the long time delays between buys and sells would hinder the

markets pricing and/or liquidity. By investing in this manner, two-sided intermediaries are able

to cultivate (or even initially supply) one side, or both sides, of their market in order to boost the

overall success of the platform.

Providing low prices or transfers to one side of the market helps the platform solve the

chicken-and-egg problem by encouraging the benefited groups participation which in turn,

due to network effects, encourages the non-benefited groups participation. Bernard Caillaud and

Bruno Jullien (2001) refer to this strategy as divide-and-conquer. Another effect of providing

benefits to one side is that this assistance can discourage use of competing two-sided firms. For

example, when Palm provides free tools and support to PDA applications software developers, it

encourages those developers to write programs that work on the Palm OS platform, but it also

induces those developers to spend less time writing programs for other operating systems (See

discussion of Palm below.)

3.2 Pricing strategies and balancing interests

Firms in mature multi-sided markets i.e. those that have already gone through the entry phase

in which the focus is on solving the chicken-and-egg problem still have to devise and maintain

an optimal pricing structure. In most observed multi-sided markets, companies seem to settle on

pricing structures that are heavily skewed towards one side of the market in the sense that the

margin (price less marginal cost as a percent of price) is far less on one side than the other. Table

1 summarizes the pricing structure for some multi-sided markets. For example, in 2001,

excluding finance charge revenue American Express earned 82 percent of its revenues from

merchants.

9

Microsoft earns the preponderance of its revenue from Windows from licensing

Windows to computer manufacturers or end-users.

10

Real estate brokers (for sales as opposed to

9

If finance charge revenues are included, American Express earned 62 percent of its revenues from merchants in

2001 (American Express Company (2001) Annual Report,

http://www.onlineproxy.com/amex/2002/ar/pdf/axp_ar_2001.pdf.).

10

From 1988 through 2000, Microsoft earned at least 67 percent of its revenues from licensing packaged software

(such as Windows and Office) to end-users (either directly at retail or through manufacturer pre-installation on

PCs). See IDC (1994) 1994 Worldwide Software Review and Forecast, Report #9358, November, IDC (1995) 1995

Worldwide Software Review and Forecast, Report # 10460, November, IDC (1996) 1996 Worldwide Software

Review and Forecast, Report #12408, November, IDC (1997) 1997 Worldwide Software Review and Forecast,

Report #14327, October, IDC (1999) 1999 Worldwide Software Review and Forecast, Report #20161, October, IDC

(2001) Worldwide Software Market Forecast Summary, 2001-2005, Report #25569, September. Note that the 67

percent figure underestimates the amount of revenue Microsoft earns from end-users because the other third of

revenue coming from "Applications Development and Deployment" includes some end-user revenues as well. For

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

197

rent) usually earn most or all of their revenues from the sellers. Political tensions can also

manifest themselves looking out for their narrow interests, customers on each side of the

market would like the other side to pay more. This is a familiar problem in the payment-card

industry in Europe a retailers association asked the European Commission to force the card

associations to eliminate the interchange fee and this tension was behind the retailer litigation

that was recently settled in the United States.

11

Discerning the optimal pricing structure is one of the challenges of competing in a multi-

sided market. Sometimes all the platforms converge on the same pricing strategy. Microsoft,

Apple, IBM, Palm and other operating system companies could have charged higher fees to

applications developers and lower fees to end-users. They all discovered that it made sense to

charge developers relatively modest fees for developer kits and, especially in the case of

Microsoft, to give a lot away for free. Nevertheless, Microsoft is known for putting far more

effort into the developer side of the business than the other operating system companies (Gawer

and Cusumano, 2002).

The debit card is an example in which different platforms made different pricing choices. In

the late 1980s, the ATM networks had a base of cardholders who used their cards to withdraw

cash or obtain other services at ATMs. They had no merchants that took these cards. To add

debit services to existing ATM cards, the ATM networks charged a small interchange fee than

the card associations charged (8 cents per transaction on a typical $30 transaction compared) to

encourage merchants to install PIN pads that could read the ATM cards that cardholders already

had and accept the pins they used to access the ATM machines (Evans and Schmalensee, 1999).

Many merchants invested in the PIN pads the number of PIN pads increased from 53,000 in

1990 to about 3.6 million in 2001.

12

The credit-card associations had a base of merchants who

took their cards but it did not have cards that, like the ATM cards, accessed consumers checking

accounts. The credit-card systems imposed a much higher interchange fee than the ATM

networks, about 37 cents versus 8 cents on a typical $30 transaction.

13

They did this to persuade

banks to issue debit cards and cardholders to take these cards.

14

The number of Visa debit cards

in circulation increased from 7.6 million in 1990 to about 117 million in 2001.

15

Two other factors influence the pricing structure. There may be certain customers on one

side of the market Rochet and Tirole refer to them as marquee buyers that are extremely

valuable to customers on the other side of the market. The existence of marquee buyers tends to

reduce the price to all buyers and increases it to sellers. A similar phenomenon occurs when

certain customers are extremely loyal to the two-sided firm perhaps because of long-term

contracts or sunk-cost investments. For example, American Express has been able to charge a

relatively high merchant discount as compared to other card brands, especially for their corporate

example, database products used by business IT departments are included in the Applications Development

category.

11

See British Retail Consortium (2002) Retail Disappointment as Visa Exempted from EU Competition Rules,

Press Release, July 25, http://www.brc.org.uk/Archive.asp, Guerrera (2002), MacKintosh (2001), and Pacelle,

Sapsford and Scannell (2003).

12

See Evans and Schmalensee (1999) and The Nilson Report (2002) No. 759, March.

13

The ATM systems typically charged a flat interchange fee per transaction, while the interchange fee set by Visa

and MasterCard varied with the size of the transaction. The reported interchange fee comparison is from 1998,

around the time of substantial growth in debit for the ATM and credit-card systems (Evans and Schmalensee, 1999).

14

Visa attracted consumers through an effective advertising campaign and attracted issuers through heavy

investment in a debit processing facility, among other strategies (Evans and Schmalensee, 1999).

15

See The Nilson Report (2002) No. 760, March and The Nilson Report (1991) No. 500, May.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

198

card, because merchants viewed the American Express business clientele as extremely attractive.

Corporate expense clients were marquee customers that allowed American Express to raise its

prices to the other side of the market, merchants. In contrast, when the ATM systems entered

into debit, they had captive cardholders ATM cards could be used for debit transactions, so

consumers did not need to be courted to accept the new payment form. Therefore, it has been the

merchants who must purchase and install expensive machinery in order to process online debit

transactions who have been courted, as we saw above.

3.3 Types of platform market structures

Several different multi-sided market organizations appear in practice. (1) Coincident platforms:

several multi-sided platforms offer substitutable products or services on the same sides. That is

the case in video games, operating systems, and payment cards. (2) Intersecting platforms:

several n-sided platforms offer products or services that are substitutable on less than n sides.

Browsers were sides of operating system and internet portal businesses. ATM networks do not

support credit cards or other cards that are not linked to the depository institution while credit

card systems do not really offer ATM cards. (3) Monopoly platforms that have no competition

on any side. Although this could exist in theory, of course, it is hard to identify any industry for

which this has been true (yellow pages was an example for a time perhaps in some places).

Another aspect of platform competition concerns the extent to which users rely

contemporaneously on more than one platform for a side. Users may be dedicated to one

platform because it is not efficient or otherwise beneficial to use more than one network. For

example, most users do not want to use more than one operating system on their personal digital

assistant. Users may also find that it is beneficial and efficient to use several competing

platforms that situation has been called multihoming. Most merchants accept payment cards

from several competing card systems.

Platform industries often have multihoming on at least one side. Table 2 presents a

summary. Consider, for example, personal computers. One could consider the two sides as

consisting of personal computer end-users and developers of applications. The end-users do not

multihome. They almost always use a single operating system and by far the preponderance of

them use a Microsoft operating system.

16

The developers do multihome. According to Josh

Lerner, in 2000, 68 percent of software firms developed software for Windows operating

systems, 19 percent for Apple computers operating systems, 48 percent for Unix operating

systems including Linux, and 36 percent and 34 percent for proprietary non-Unix operating

systems that run on minicomputers and proprietary operating systems that run on mainframes

respectively.

17

In fact, in recent years the percentage of software firms developing for non-

Microsoft operating systems has increased. The fastest-growing category has been software

firms developing for Unix operating systems including Linux. The percentage of developers in

this category increased from 29 percent in 1998 to 48 percent in 2000.

18

Multihoming and intersecting platforms affect both the price level and the pricing structure.

Theory and empirics are not far enough advanced to say much more.

16

IDC (2001) Worldwide Software Market Forecast Summary, 2001-2005, Report #25569, September.

17

The percentages total to 205, indicating substantial multihoming on the part of developers. See Lerner (2002) and

Corporate Technology Directory (1990-2000).

18

See Lerner (2002) and Corporate Technology Directory (1990-2000).

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

199

Two-Sided Platform Side One Presence of Multihoming for Side One Side Two Presence of Multihoming for Side Two

Residential Property

Brokerage

Buyer Uncommon: Multihoming may be unnecessary, since an MLS allows

buyers to see property listed by all member agencies.

a

Seller Uncommon: Multihoming may be unnecessary, since an

MLS allows the listed property to be seen by all member

agencies customers.

a

Securities Brokerage Buyer Common: The average securities brokerage client has accounts at

three firms.

b

Note that clients can be either or both buyers or sellers.

Seller Common: The average securities brokerage client has

accounts at three firms.

b

As mentioned, clients can be either

or both buyers or sellers.

Business-2-Business Buyer Varies: For example, multihoming may be unnecessary for some

online B2B sites, since buyers can go directly to the B2B platform

instead of contacting multiple individual suppliers.

c

Seller Varies: Multihoming may be unnecessary since the B2B

can inexpensively reach a large audience.

d

Peer-2-Peer Buyer Varies: Multihoming may be unnecessary for buyers using online

auction sites since eBay holds 85% of the market share (i.e. it seems

that most people purchase their online auction products at eBay).

Alternatively, multihoming may be more common for online dating

services where there are many sites and a large audience of online

singles (considered to be available singles, as opposed to buyers).

e

Seller Varies Multihoming may be unnecessary for sellers using

online auction sites since eBay holds 85% of the market

share (i.e. it seems that most people auction their products

at eBay). Alternatively, multihoming may be more common

for online dating services where there are many sites and a

large audience of online singles (considered to be available

singles, as opposed to sellers).

e

Newspapers and

Magazines

Reader Common: In 1996, the average number of magazines issues read per

person per month was 12.3.

f

Advertiser Common: For example, Sprint advertised in the New York

Times, Wall Street Journal, and Chicago Tribune, among

many other newspapers, on Aug. 20, 2002.

g

Network Television Viewer Common: For example, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Houston,

among other major metropolitan areas, have access to at least four

main network television channels: ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC.

h

Advertiser Common: For example, Sprint places television

advertisements on ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC.

i

Operating System Application

User

Uncommon: Individuals typically use only one operating system.

j

Application

Developer

Common: As noted earlier, the number of developers that

develop for various operating systems indicates that

developers engage significant multihoming.

k

Video Game Console Game

Player

Varies: The average household (that owns at least one console) owns

1.4 consoles.

l

Game

Developer

Common: For example, Electronic Arts, a game developer,

develops for Nintendos GameCube, Microsofts Xbox, and

Sonys Playstation 2, among other consoles.

m

Payment Card Cardholder Common: Most American Express cardholders also carry at least one

Visa or MasterCard.

n

Merchant Common: American Express cardholders can use Visa and

MasterCard at almost all places that take American

Express.

n

Table 2: The presence of multihoming in selected two-sided platforms

Notes:

a

See Frew and Jud (1987);

b

See Scherreik (2002);

c

See Lucking-Reilly and Spulber (2001);

d

See Federal Trade Commission Staff (2000) Entering the 21st Century:

Competition Policy in the World of B2B Electronic Marketplaces: Efficiencies of B2B Electronic Marketplaces, October, http://www.ftc.gov/os/2000/10/index.htm#26;

e

See Cisneros (2000) and Festa (1996);

f

See FCB (1998) Magazines in the Information Age, Media Research Report, Spring,

http://www.magazine.org/resources/research/fcb_magazines_infoage.html;

g

See New York Times (2002), Wall Street Journal (2002), and Chicago Tribune (2002);

h

See

ABC (2002) Local Stations, http://abc.abcnews.go.com/site/localstations.html., CBS (2002) CBS Info, http://www.cbs.com/info/hdtv/., FOX (2002) Fox Affiliates,

http://www.fox.com/links/affiliates.htm., and NBC (2002) Local Stations, http://www.nbc.com/nbc/header/Local_Stations/;

i

See Fisher (1997);

j

See Hacker (2001);

k

See

Lerner (2002) and Corporate Technology Directory (1990-2000);

l

See Yankee Group (2001) Video-Game Penetration Grows to 36 Million Households in 2001, Reuters

News, November 19, http://about.reuters.com/newsreleases/art_19-11-2001_id785.asp;

m

See Game Makers Hedge Bets in Console Wars (2001) USA Today, November

16, http://www.usatoday.com/life/cyber/tech/review/games/2001/11/19/game-makers.htm;

n

See Evans and Schmalensee (1999).

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

200

3.4 Scaling and liquidity

Successful multi-sided firms such as Microsoft, eBay, Yahoo!, and Diners Club, have taken

time to test and tweak their platforms to build liquidity before making major investments.

These firms established presence in small markets first, and used trial and error to identify the

correct technology and operations infrastructure in which to invest. Many successful multi-

sided firms seem to adopt a fairly gradual entry strategy in which they scale up their platform

over time. Though much of the network economics literature may suggest that the multi-

sided firm should rely on the right initial investments to help build liquidity over time, it is

often difficult to predict just what the right technology and operations infrastructure will be.

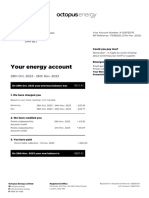

Therefore, successful multi-sided firm seem to found it advantageous to establish efficient

buy-seller transactions first, and make large investments only after the platform has been

tested. For instance, eBay expanded outside the collectibles market only when users started

listing such items up for sale. Figure 1 below outlines the growth of eBays sales categories.

It shows the gross merchandise sales per category in the third quarter of 2002 broken down

by category. The three categories collectibles, early practicals, and practicals are grouped

by the year they debuted.

Category Q3-02 (millions) Yr/Yr

Collectibles:

Collectibles $920 11% Debuted First ~ 1995

Coins & Stamps $400 51%

Early Practicals:

Computers $1,600 44% Debuted Second ~1997

Consumer Electronics $1,400 78%

Books, Movies, Music $1,200 44%

Sports $1,000 35%

Practicals:

Motors $3,800 116% Debuted Third ~ 1999

Clothing $700 98%

Home & Garden $470 90%

Figure 1: eBays category growth

19

Palm also did not invest large amounts into developer support until it achieved sufficient

liquidity on the user side of the market. While small investments were made in releasing a

software development kit (SDK) with the Palm Pilot and making the Palm OS and

architecture accessible to outside developers, Palm made few efforts to sign up key

development partners or to support the Palm development community through classes,

conferences, and other community support activities until a critical mass of users was

assembled in 1998. (See discussion of Palm below.)

Many successful multi-sided firms have tested and modified their platforms with minimal

investment and then scaled up according to what works best. An example comes from

Yahoo!, a firm that has, over time, experimented with providing pages geared to different

audiences such as Yahoo!Personals, Yahoo!Finance, and Yahoo!Travel. In 1996, Yahoo!

developed Yahooligans!, a directory site that linked to content that appealed to children.

20

Yahoo! invested only one programmer and one business developer in their early efforts on

19

See eBay Inc. (2001) Annual Report.

20

See http://www.yahooligans.com.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

201

Yahooligans!, both working half time for three months before the launch. As it turned out,

the bandwidth available to most children at the time 28 kbps was too slow to allow for

content that kept kids attention. Yahooligans! was a relative failure among Yahoo! pages at

the time, but that failure came at a minimal loss to Yahoo! (Bergin, 1998).

A final observation on business models. Contrary to the traditional economic theory of

network effects (Arthur, 1989) and the business advice based on that theory (Shapiro and

Varian, 1999), there is no evidence that building up market share quickly is a recipe for

market domination in platform industries most, if not all of which, are precisely those

industries that economists have cited as having strong network effects. Many of the early

entrants in these industries ultimately did not retain the leadership position: Diners Club in

cards, Apple in personal computer, Apple in hand-held devices, and OnSale in on-line

exchanges. Also, as noted above, despite network effects many platform industries have

several overlapping competing platforms and most have multi-homing on at least one side.

4 Diners Club and pricing in the payment card industry

Frank McNamara, the president of a New York credit company, was having lunch in

Manhattan in 1949. A year later he had a thriving business based on this experience.

According to Newsweek:

21

Halfway through his coffee, McNamara made a familiar, embarrassing discovery; he had left his

wallet at home. By the time his wife arrived and the tab had been settled, McNamara was deep in

thought. Result: the Diners Club, one of the fastest-growing service organizations.

McNamara and an associate, Ralph Schneider, started small. Beginning with less than $1.6

million (in 2002 dollars)

22

of start-up capital they signed up 14 New York restaurants,

charging them 7 percent of the tab, and initially gave cards away to people.

23

(The observant

reader will note that for must of us owning a credit card would not help our predicament

when we leave our wallets at home. The proverbial apple falling on the head is a mysterious

force.)

By its first anniversary there were 42,000 cardholders who were each paying $18 year for

membership in the club. There were 330 U.S. restaurants, hotels and nightclubs that

accepted these cards; they paid an average of 7 percent of the cardholders bill to Diners

Club. In March 1951, Diners Club handled about $3 million of exchanges between

cardholders and merchants (it reportedly made almost $60,000 in profit before taxes).

24

In

1951 Frank McNamara, founder of Diners Club, predicted that monthly transaction volume

would increase to about $7 million by the end of the year.

25

Diners Club was therefore getting

more than three quarters of its revenues from merchants.

26

Moreover, the margin on

cardholders was low since they were getting free float for an average of two weeks.

By 1958, it had raised the cardholder fee to about $26 but left the merchant fee at 7

percent. Nevertheless, it continued to earn most of its revenues, about 70 percent, from

merchants.

27

The same year saw the birth of two of the major competitors to Diners Club.

American Express, which had long been in the travel and entertainment business with its

travelers checks and travel offices, decided to enter the industry. It recognized need to get

21

Dining on the Cuff (1951) Newsweek, January 29.

22

Except where noted, all dollar figures in this paper have been adjusted to constant 2002 dollars.

23

See Mandell (1990) and Grossman (1987).

24

Charge It, Please (1951) Time, April 9.

25

Dining on the Cuff (1951) Newsweek, January 29.

26

Cardholder fees totaled about $745,000 while merchant fees totaled about $2.5 million.

27

On-the-Cuff Travel Speeds Up (1958) Business Week, August 16.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

202

both sides on board. Even before the first transaction, it had already acquired a cardholder

base of 150,000 from the American Hotel Associations card program, as well as the

programs 4,500 hotels for its merchant base. It bought another 40,000 cardholders from

Gourmet magazines dining card program (Grossman, 1987). It soon had a cardholder base to

sell to T&E merchants, and sent out representative to sign them up. It also advertised in

newspapers for additional cardholders (Grossman, 1987). American Expresss positive

reputation in the T&E industry was also a benefit in attracting both sides of the business

(Grossman, 1987). By the time of its entry on October 1958, it already had 17,500 merchant

locations and 250,000 cardholders (Grossman, 1987).

American Express adopted a slightly different pricing policy than Diners Club. It initially

set its annual fee at $31, $5 higher than Diners Club, thereby suggesting that it was the more

exclusive card (Friedman and Meehan, 1992). But it set the initial merchant discount

slightly lower: 5 to 7 percent for restaurants; and 3 to 5 percent for the recalcitrant hotel

industry.

28

Within a year, its cardholder base had grown to 700,000 and its merchant base to

37,000.

29

With its slightly higher cardholder fee and slightly lower merchant fee, American

Express received just under 55 percent of its revenue from merchants, compared to over 65

percent for Diners Club in 1959.

30

This would grow over time, however, as spending per card

increased faster than annual fees.

American Express had been successful getting both sides on board but initially struggled

to make a profit. It responded by putting more pressure on cardholders to pay promptly. It

also managed to raise cardholder fees without suffering significant attrition. There were

900,000 cardholders that could use their cards at 82,000 merchant locations by the end of

1962, the first year that the card operation posted a small profit (Hammer, 1962).

The other significant entrant in 1958 was Bank of America (this card evolved into Visa).

Unlike many other banks, it had always focused on lending money to the middle class. By

1958, Bank of America had extensive experience in making small loans on consumer

durables such as refrigerators and automobiles. It had also become the largest bank in the

country (Mandell, 1990).

One of its small competitors, the First National Bank of San Jose, started a charge card in

1953. At the time, Bank of America considered introducing its own card but decided that

there was not a good enough business case. After studying the emerging industry over the

next few years they decided to introduce a credit card. Credit-worthy customers would

receive cards with limits of either $1,600 or $2,600; prior authorization would be required for

purchases over $130; and a revolving credit option was available for some cardholders

(Wolters, 2000). Revolving credit was the feature that distinguished this card from existing

charge cards. The merchant fee was initially set at 5 percent and lowered soon thereafter

(Wolters, 2000). Cardholders did not pay an annual fee but paid finance charges on any

revolved balances at an annual interest rate of 18 percent (Wolters, 2000). This was a more

merchant-friendly balance than that set by Diners Club or American Express, especially

considering that Bank of Americas card was also extending credit on a revolving basis.

Bank of America did a market test in Fresno in the fall of 1958. Three hundred retailers

signed up initially, and every Bank of America customer in the Fresno area received a card.

According to one study, This mass mailing of 60,000 cards had been Williams (the Bank of

America leader of the effort) solution to the problem of how to convince retailers that enough

individuals would possess a card to make their participation in the program worthwhile. His

28

On-the-Cuff Travel Speeds Up (1958) Business Week, August 16.

29

Towards an Ever-Fuller Life on Credit Cards (1959) Newsweek, September 28.

30

Figures taken from Newsweek 1959 article, and assuming average of 5 percent for Amex per Newsweek 1958

article.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

203

solution worked, for during the next five months another eight hundred Fresno-area retailers

joined the newly named BankAmericard program (Wolters, 2000). They expanded

throughout the state during the following year. By the end of 1959, 25,000 merchants

accepted the card and almost two million California households had one.

Things did not go well. Fraud was rampant. The number of delinquent accounts was five

times higher than expected. Large retailers resisted joining. The program lost $45 million in

1960. The bank worked on collection problems and lowered the merchant fee to as low as

three percent to entice retailers. Delinquencies declined and the merchant base increased to

35,000 in 1962. It was profitable by the early to mid 1960s.

One notable common theme across the experiences of the three startups is the importance

of getting both sides on board. Diners Club, starting from scratch and trying to sell a new

product, had to build slowly. It set a relatively cardholder-friendly balance, collecting most of

its revenues from merchants. This made it possible to sign up cardholders even before a

significant merchant base had been signed. The cardholder base could then be used, of

course, to sign up merchants. By the time of American Expresss entry, the idea of a charge

card had already been established by Diners Club and others. American Express was able to

capitalize on that by entering at a larger scale. Indeed, it probably did not have the option of

entering as gradually as Diners Club did, since what cardholders or merchants would sign up

with a fledgling American Express card given the option of an established alternative.

American Express therefore bought up customer bases on both sides before it entered. It was

also able to use its established position in the T&E business to set a slightly higher

cardholder fee, to cultivate the upscale image that served it well for a long time.

Bank of America also developed a large cardholder base in entering the business. It used

its base of depository customers, the largest in California, to develop an instant cardholder

base, which it then used to sign up merchants. Even with its prominent position among

consumers in California, however, Bank of America had to strike a more merchant-friendly

balance, lowering its merchant fees until it could get enough merchants on board.

Perhaps as a consequence of entering at a larger scale, both American Express and Bank

of America, unlike Diners Club, had a hard time making a profit early on. Diners Club made

a profit in its first year, while the other two firms did not see a profit until their fourth or fifth

years. It took time to weed out delinquent cardholders. Having to make an upfront investment

in building a profitable cardholder base is a lesson that holds even for new card issuers today

(although they can join Visa or MasterCard and do not have to build an entire system). There

were also the operational problems that would be expected in starting up any new business.

Bank of America had such (misplaced) confidence its customers would pay their bills that it

did not even set up a collections department (Nocera, 1994).

5 The Palm OS and community-building in software platforms

Palm was founded in 1992 as an effort to develop software applications for personal digital

assistants (PDAs). In 1993, Palm released the Zoomer in collaboration with five other

companies Casio, GeoWorks, Tandy, Intuit, and America Online. Palm was responsible for

the application development while the other five companies handled the hardware, the

operating system, and distribution. The Zoomer, with its high price ($820) and poor

handwriting recognition, ultimately failed with only 15,000 units sold (Gawer and

Cusumano, 2002). Zoomer was not the first failure. Apple had made the first attempt with its

Apple Newton in 1993. Other entrants into the PDA market from 1993 to 1996 were the

Psion Series 3, Hewlett-Packard LX, Hewlett-Packard OmniGo, Sharp Zaurus, Sharp Wizard,

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

204

and Microsofts Windows CE

31

PDAs. With the exception of the Windows CE PDA, all

followed an integrated strategy where the PDA manufacturer produced the hardware,

operating system, and applications. Windows CE PDAs had a non-integrated strategy, where

the hardware, operating system, applications were all developed by different firms (although

Microsoft did end up writing the operating system as well as many applications for Windows

CE). The integration of application and operating system development within one firm was

common in the software industry, for example Microsoft produced some of the most popular

applications for the Windows OS (Evans, 2003).

Palm re-entered the handheld market in 1996 with the Palm Pilot. This integrated

hardware, an operating system, and some applications. Palm overcame the handwriting

recognition hurdle with the invention the Graffiti text entry method, providing users a simple

method to enter text. Industry experts described Graffiti as the killer app for the Palm Pilot

(Feldstein and Flanagan, 2001). The pricing of the Palm Pilot also reflected Palms desire to

have deep market penetration. While 3Com, Palms parent company from June 1997 to

March 2000, wanted Palm to price the Palm Pilot high to extract profits, Palm insisted that

prices be kept low to expand the user base (Gawer and Cusumano, 2002). The Palm Pilots

combination of low price and robust features were a hit with consumers and provided the

most bang for the buck (Atluru and Wasserstein, 1998). The Palm Pilot met immediate

success with over 360,000 units sold in 1996, representing 51 percent share of the market

(Atluru and Wasserstein, 1998).

32

Palm has gone through three stages in developing what is now a three-sided platform

business. In the first phase from about 1996 to 1998, it entered as an integrated platform. It

made the hardware, operating system, and applications for the Palm Pilot and integrated them

together. It planned to court developers, however, only after it had a significant user base.

According to Donna Dubinsky, CEO and one of its founders, We are a highly integrated

product that delivers end user results. We are not having a developer conference until we sell

a million units (Atluru and Wasserstein, 1998). A developer conference is one of the major

methods used by software platforms to stimulate the writing of applications. Nevertheless,

even during this initial phase Palm laid the groundwork for getting a developer community

on board.

33

In early 1996, Palm released its first software development kit (SDK), which

included the source code for the Palm Pilots bundled applications. This source code served

as a model that outside developers could reference to build other applications (Gawer and

Cusumano, 2002).

In 1998, Palm sold over 2 million PDAs and launched the second phase of market

development. Palm invested resources in persuading developers to write applications for the

Palm OS. It offered business development resources to developers, including joint

development, marketing, and bundling. Palms most important business development

resource was its software development forums (SDF), which helped external developers start

and grow their own businesses. The SDF offered advisory meetings, business seminars,

workshops, and networking events. It also started a $54 million venture capital unit called

Palm Ventures to support businesses focusing on Palm OS applications. The company also

offered Palm OS development classes regularly, and encouraged other activities among its

community of users through developer portals (Gawer and Cusumano, 2002). The strategy to

actively get developers on board was successful. The number of registered developers grew

31

Windows CE was renamed Pocket PC at version 6.0.

32

This represents market share of Palm hardware PDA and does not include licensed Palm OS devices.

33

In fact, in the first year of release, the Palm attracted over 2,000 third-party developers to its platform without

any developer support efforts (Atluru and Wasserstein, 1998).

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

205

from 7,500 in 1998 to 220,000 in 2002.

34

Palm continued to secure its market leadership,

with over 7 million units shipped by 2000.

The third phase, from about 2001 to the present, has moved Palm closer to being a pure

operating system company. Palm has created alliances with Sony, Nokia, Handspring, IBM,

Qualcomm, Supra, Symbol Technologies, Fossil

35

, and TRG Products to create PDAs and

other computer appliances based on the Palm OS (Gawer and Cusumano, 2002). Palm has

reported that this greatly increases the market share of Palm OS based PDAs over their

potential market share with an integrated strategy.

36

In addition, Palm OS licensing has

expanded the scope of the Palm OS beyond traditional PDAs to such devices as wrist watches

(Fossil Wrist PDA), cellular phones (Handspring Treo), and multimedia players (Sony Cli).

While Palm manufactured PDAs claimed 50 percent of the market in 2000, devices powered

by the Palm OS operating system had over 75 percent share of the worldwide personal

companion device market according to a report by International Data Corporation.

37

This

market share increased to over 82 percent by the second half of 2002.

38

In January 2002 as

Palm powered devices hit 20 million sold, Palm formed a Palm OS platform subsidiary,

PalmSource, further separating the Palm OS from Palms hardware solutions.

39

Palm claims that its operating system was designed from the start to provide a platform

for these three sides. According to Palms web site,

From the start, the flexible, extensible Palm OS has been designed to grow and evolve in

response to user needs. The open, modular architecture allows our more than 50,000

developers, licensees, alliance, and OEM partners to develop innovative new products and

applications for a rapidly expanding global market (Gawer and Cusumano, 2002).

Palm has subsidized both the application developer side of the market and the user side of

the market by licensing their operating system at a loss and giving their development tools

away for free. It is able to do this because of its profits in hardware sales. Palm provides an

SDK, Palm OS Emulator, Palm OS Simulator, and sample source code free for download on

its web site. Palm also provides links to third-party integrated development environments,

both free and not, for download on their web site.

40

Palm also offers an online developer

support program to offer a full range of development services. The Basic Level Membership

is offered at no cost. The Advanced Level Membership is available for just $500 per year and

includes direct technical, marketing and training support.

41

Only a small percentage of Palms

revenues were from licensing of the Palm OS. PalmSource revenues totaled $67, $88, and

$50 million, while operating loss totaled $17, $8, and $8 million in fiscal years 2002, 2001

and 2000, respectively.

42

This continued loss of PalmSource represents Palms continued

efforts in trying to expand the user base of the Palm platform.

34

Palm, Inc. (1998) Key Strategic Relationships And Growth To 7,500 Developers Propel 3Com Palm

Computing Platform Into Corporate America, June 15, http://www.palm.com/pr/enterprise.html; Palm, Inc.

(2002) Annual Report.

35

Palm, Inc. (2002) Fossil Signs License Agreement with PalmSource For First Ever Palm Powered Wrist

Devices, November 18, http://www.palmsource.com/press/2002/111802.html.

36

Palm, Inc. (2001) Annual Report.

38

Palm, Inc. (2003) Palm Powered Share Increases in Second Half of 2002, January 27,

http://www.palmsource.com/press/2003/012703.html.

39

Palm, Inc. (2002) Palm Completes Formation of Palm OS Subsidiary as Palm Powered Devices Hit 20

Million Sold, January 21, http://www.palmsource.com/press/2002/012102.html.

40

Palm, Inc. (2003) PalmOS: Desktop Development, http://www.palmos.com/dev/tools.

41

Palm, Inc. (2003) PalmOS.com: Palm OS Developer Program, http://www.palmos.com/dev/programs/pdp.

42

Palm, Inc. (2002) Annual Report.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

206

6 Summary

Multi-sided platform markets are becoming an increasingly important part of the economy.

They range from relatively small emerging companies like eBay, Yahoo!, and Palm, to

relatively large and mature companies like American Express. These markets also have had a

large impact on the recent information technology boom, and undoubtedly, they will continue

to be important, as internet based commerce expands its scope to include both new and old

economy firms. In addition to internet commerce, other increasingly important industries,

such as credit cards, operating systems, shopping centers, and mass media, are all governed

by the economics of multi-sided platforms.

While it is not my intention to generalize from a small sample, and many issues need to

be investigated in more depth, a number of business models appear common across both the

cases studied here. First, differential pricing is used to get both sides on board. Second, once

both sides are on board, pricing continues to play a key role in maintaining both sides of the

platform. Third, multihoming often occurs in multi-sided platforms. And, fourth, one solution

to the pricing complexity that has been used successfully is to start with a small but scalable

platform.

7 References

Armstrong, Mark (2002) Competition in Two-Sided Markets, Nuffield College, Oxford,

Working Paper.

Arthur, W. Brian (1989) Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In By

Historical Events, The Economic Journal, 99: 116-131.

Atluru, Rajesh and Kevin Wasserstein (1998) Palm Computing: The Pilot Organizer,

Harvard Business School.

Baumol, William, John C. Panzar and Robert D. Willig (1982) Contestable Markets and The

Theory of Industry Structure, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York.

Becker, David (2000) Revenue from Game Consoles will Plunge, Report Predicts, CNET

News.com, July 31, http://techrepublic-cnet.com.com/2100-1040-43841.html?legacy=cnet.

Becker, David (2002) Xbox Drags on Microsoft Profit, CNET News.com, Jan. 18,

http://news.com.com/2100-1040-818798.html.

Bergin, Richard (1998) Interview with Yahoo! Senior Vice President Tim Brady, Harvard

Business School, doctoral research.

Caillaud, Bernard and Bruno Jullien (2001) Chicken & Egg: Competing Matchmakers,

Center For Economic Policy Research, Working Paper No. 2885.

Cisneros, Oscar S (2000) Ebay Accused of Monopolization, Wired News, July 31,

http://www.wired.com/news/print/0,1294,37871,00.html.

Evans, David S. (2003) The Antitrust Economics of Multi-Sided Platform Markets, Yale

Journal on Regulation (forthcoming).

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

207

Evans, David S. and Richard Schmalensee (1999) Paying with Plastic: The Digital

Revolution in Buying and Borrowing, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Fahey, Rob (2002) MS to Lose J525M on Xbox This Year, GameIndustry.biz, June 26,

http://www.gamesindustry.biz/content_page.php?section_name=pub&aid=210.

Feldstein, Janet and Christopher Flanagan (2001) Handspring Partnerships, Harvard

Business School.

Ferguson, James M. (1983) Daily Newspaper Advertising Rates, Local Media Cross-

Ownership, Newspaper Chains, and Media Competition, Journal of Law and Economics,

26: 635-654.

Festa, Paul (1996) Looking for Love Online, CNET News.com, December 17, 1996

http://news.com.com/2100-1023-255523.html?tag=rn.

Fisher, James (1997) An Ad Blitz for the 21

st

Century, Sprint Press Release, September 24,

http://www3.sprint.com/PR/CDA/PR_CDA_Press_Releases_Detail/0,3245,,00.html?ID=129

4.

Frew, J. and G. Jud (1987) Who Pays the Real Estate Brokers Commission? Research in

Law and Economics: The Economics of Urban Property Rights, 10: 177-188.

Friedman, Jon and John Meehan (1992) House of Cards: Inside the Troubled Empire of

American Express, Putnam, New York.

Gawer, Annabelle and Michael A. Cusumano (2002) Platform Leadership, Harvard Business

School Press, Boston, MA.

George, Lisa and Joel Waldfogel (2000) Who Benefits Whom in Daily Newspaper

Markets? NBER Working Paper #7944.

Goettler, Ronald. (1999) Advertising Rates, Audience Composition, and Competition in the

Network Television Industry, Carnegie Mellon University GSIA Working Paper #1999-E28.

Grossman, Peter (1987) American Express: The Unofficial History of the People Who Built

the Great Empire, Crown Publishers, New York.

Guerrera, Francesco (2002) Brussels Set to Let Visa off the Hook, Financial Times, May

13.

Hacker, Scot (2001) He Who Controls the Bootloader, Byte, August,

http://www.byte.com/documents/s=1115/byt20010824s0001/0827_hacker.html.

Hammer, Alexander R. (1962) American Express Raises Profit: Credit Card Unit in the

Black, The New York Times, April 25.

Jeon, Doh-Shin, Jean-Jacques Laffont, and Jean Tirole (2001) On the Receiver Pays

Principle, mimeo.

Jullien, Bruno (2001) Competing in Network Industries: Divide and Conquer, Institut

DEconomie Industrielle, Working Paper No. 9.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

208

Lerner, Abba (1934) The Concept of Monopoly and the Measurement of Monopoly Power,

Review of Economic Studies, 1: 157-175.

Lerner, Josh (2002) Did Microsoft Deter Software Innovation? Working Paper,

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID269498_code010528670.pdf?abstractid=2

69498.

Lucking-Reilly, David. and Daniel F. Spulber (2001) Business-to-Business Electronic

Commerce, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15: 55-68.

MacKintosh, James (2001) Watchdog Rules Credit Card Fees to Retailers Excessive,

Financial Times, September 26.

Mandell, Lewis (1990) The Credit Card Industry: A History, Twayne Publishers, Boston,

MA.

Nocera, Joseph. (1994) A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class,

Simon & Schuster, New York.

Pacelle, Mitchell, Jathon Sapsford and Kara Scannell (2003) Visa to Settle With Retailers

for $2 Billion, The Wall Street Journal, May 1.

Parker, Geoffrey and Marshall W. Van Alstyne (2002) Unbundling the Presence of Network

Externalities, Working Paper,

http://www.idei.asso.fr/Commun/Conferences/Internet/Janvier2003/Papiers/VanAl.pdf.

Pashigian, B. Peter and Eric D. Gould (1998) Internalizing Externalities: The Pricing of

Space in Shopping Malls, Journal of Law and Economics, 41: 115-142.

Rochet, Jean-Charles (2003) The Theory of Interchange Fees: A Synthesis of Recent

Contributions, Working Paper.

Rochet, Jean-Charles and Jean Tirole (2002) Cooperation Among Competitors: Some

Economics of Payment Card Associations, Rand Journal of Economics, 33: 549-570.

Rochet, Jean-Charles and Jean Tirole (2003) Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets,

Journal of the European Economics Association (forthcoming).

Ronan, Courtney (1998) Apartment Locaters: How Do They Make Their Money? Realty

Times, June 30, http://realtytimes.com/rtnews/rtcpages/19980630_aptlocator.htm.

Rysman, Marc (2002) Competition Between Networks: A Study of the Market for Yellow

Pages 1-2, Boston University Industrial Studies Project, Working Paper No. 104.

Scherreik, Susan (2002) Is Your Broker Leaving You Out in the Cold? Business Week,

http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/02_07/b3770110.htm.

Schiff, Aaron (2003) Open and Closed Systems of Two-Sided Networks, Information

Economics and Policy, forthcoming.

Shapiro, Carl and Hal R. Varian (1999) Information Rules, Harvard Business School Press,

Boston, MA.

Review of Network Economics Vol.2, Issue 3 September 2003

209

Wolters, Timothy (2000) Carry Your Credit Card in Your Pocket: The Early History of the

Credit Card at Bank of America and Chase Manhattan, Enterprise and Society, 1: 315-354.

Wong, Wylie (1998) Netscape Applauds Microsoft Suit, TechWeb, May 20,

http://www.techweb.com/wire/story/msftdoj/TWB19980519S0007.

You might also like

- A New Friend WBDocument1 pageA New Friend WBJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam - 1 Prim - 2018 - Unit 2Document1 pageEnglish Exam - 1 Prim - 2018 - Unit 2Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- Wildlife HorDocument1 pageWildlife HorJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- The Biggest BirdDocument1 pageThe Biggest BirdJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam - 1 Sec. Unit - 1 2019Document1 pageEnglish Exam - 1 Sec. Unit - 1 2019Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- CONTENT Qs-1 - Factual and Inference Questions-Converted-3-4Document2 pagesCONTENT Qs-1 - Factual and Inference Questions-Converted-3-4Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- CONTENT Qs-1 - Factual and Inference Questions-Converted-5-6Document2 pagesCONTENT Qs-1 - Factual and Inference Questions-Converted-5-6Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- Countries and LanguagesDocument1 pageCountries and LanguagesJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- Worksheet - Telling TimeDocument1 pageWorksheet - Telling TimeJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- Academic Text: By: Mg. Jorge GonzaDocument4 pagesAcademic Text: By: Mg. Jorge GonzaJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- CONTENT Qs-1 - Factual and Inference Questions-Converted-7-8Document2 pagesCONTENT Qs-1 - Factual and Inference Questions-Converted-7-8Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- "San Antonio de Padua": ENGLISH EXAM - 1st Grade - SecondaryDocument1 page"San Antonio de Padua": ENGLISH EXAM - 1st Grade - SecondaryJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- CONTENT Qs-1 - Factual and Inference Questions-Converted-9-12Document4 pagesCONTENT Qs-1 - Factual and Inference Questions-Converted-9-12Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- TOEFL Factual and Inference QuestionsDocument2 pagesTOEFL Factual and Inference QuestionsJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- Academic TextDocument4 pagesAcademic TextJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- User Guide For The Operations of The Fx-CG20.: Graphic CalculatorDocument52 pagesUser Guide For The Operations of The Fx-CG20.: Graphic CalculatorJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH EXAM - 3rd Grade - Secondary: "San Antonio de Padua"Document1 pageENGLISH EXAM - 3rd Grade - Secondary: "San Antonio de Padua"Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam - 1 Prim - Unit 3Document2 pagesEnglish Exam - 1 Prim - Unit 3Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam - Prim 3 - JulioDocument1 pageEnglish Exam - Prim 3 - JulioJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH EXAM - 2nd Grade - Secondary: "San Antonio de Padua"Document1 pageENGLISH EXAM - 2nd Grade - Secondary: "San Antonio de Padua"Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH EXAM - 4th Grade - Secondary: "San Antonio de Padua"Document1 pageENGLISH EXAM - 4th Grade - Secondary: "San Antonio de Padua"Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam - Sec 5 - JulioDocument1 pageEnglish Exam - Sec 5 - JulioJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH EXAM - 2nd Grade - Secondary: "San Antonio de Padua"Document1 pageENGLISH EXAM - 2nd Grade - Secondary: "San Antonio de Padua"Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH EXAM - 2nd Grade - Primary: I. Write The NumbersDocument2 pagesENGLISH EXAM - 2nd Grade - Primary: I. Write The NumbersJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam for 1st Grade StudentsDocument1 pageEnglish Exam for 1st Grade StudentsJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH EXAM - 2nd Grade - Primary: I. Write The NumbersDocument2 pagesENGLISH EXAM - 2nd Grade - Primary: I. Write The NumbersJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam for 1st Grade StudentsDocument1 pageEnglish Exam for 1st Grade StudentsJorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam 2 Bim - Prim 4Document1 pageEnglish Exam 2 Bim - Prim 4Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam 2 Bim - Prim 4Document1 pageEnglish Exam 2 Bim - Prim 4Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- English Exam 2 Bim - Sec 1Document1 pageEnglish Exam 2 Bim - Sec 1Jorge GonzaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)