Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Precautionary Principle

Uploaded by

John Osborne0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

320 views4 pagesWHAT IS THE PRECAUTIONARY PRINCIPLE?

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentWHAT IS THE PRECAUTIONARY PRINCIPLE?

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

320 views4 pagesThe Precautionary Principle

Uploaded by

John OsborneWHAT IS THE PRECAUTIONARY PRINCIPLE?

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

THE PRECAUTIONARY PRINCIPLE

The precept that an action should not be taken if the

consequences are uncertain and potentially dangerous

The principle and the main components of its implementation are stated this way in the 1998

Wingspread Statement on the Precautionary Principle:

"When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures

should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. In

this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public, should bear the burden of proof. The

process of applying the precautionary principle must be open, informed and democratic and must

include potentially affected parties. It must also involve an examination of the full range of

alternatives, including no action." - Wingspread Statement on the Precautionary Principle, Jan. 1998

Sometimes if we wait for certainty it is too late. Scientific standards for demonstrating cause and

effect are very high. For example, smoking was strongly suspected of causing lung cancer long

before the link was demonstrated conclusively. By then, many smokers had died of lung cancer. But

many other people had already quit smoking because of the growing evidence that smoking was

linked to lung cancer. These people were wisely exercising precaution despite some scientific

uncertainty.

When evidence gives us good reason to believe that an activity, technology, or substance may be

harmful, we should act to prevent harm. If we always wait for scientific certainty, people may suffer

and die and the natural world may suffer irreversible damage.

Precaution does not work if it is only a last resort and results only in bans or moratoriums. It is best

linked to these implementation methods:

exploring alternatives to possibly harmful actions, especially clean technologies that

eliminate waste and toxic substances;

placing the burden of proof on proponents of an activity rather than on victims or potential

victims of the activity;

setting and working toward goals that protect health and the environment; and

bringing democracy and transparency to decisions affecting health and the environment.

Q. Why do we need the precautionary principle now?

A. The effects of careless and harmful activities have accumulated over the years. Humans and the

rest of the natural world have a limited capacity to absorb and overcome this harm. There are plenty

of warning signs:

Chronic diseases and conditions affect more than 100 million men, women, and children in the

United Statesmore than a third of the population. Cancer, asthma, Alzheimer's disease,

autism, birth defects, developmental disabilities, diabetes, endometriosis, infertility, multiple

sclerosis, and Parkinson's disease are becoming increasingly common.

In laboratory animals, wildlife, and humans, considerable evidence documents a link between

levels of environmental contamination and malignancies, birth defects, reproductive problems,

impaired behavior, and impaired immune system function. Scientists' growing understanding

of how biological systems develop and function leads to similar conclusions.

Other warning signs are the dying off of plant and animal species, the destruction of

ecosystems, the depletion of stratospheric ozone, and the likelihood of global warming.

Five Key Elements of the Precautionary Principle

The Precautionary Principle represents a paradigm shift in decision-making. It allows

for five key elements that can prevent irreversible damage to people and nature:

1. Anticipatory Action: There is a duty to take anticipatory action to prevent harm.

Government, business, and community groups, as well as the general public, share

this responsibility.

2. Right to Know: The community has a right to know complete and accurate

information on potential human health and environmental impacts associated with

the selection of products, services, operations, or plans. It is the responsibility of the

proponent of change to demonstrate that there is no risk; it is not the responsibility of

those who are concerned to demonstrate that there is risk.

3. Alternatives Assessment: An obligation exists to examine a full range of

alternatives and select the alternative with the least potential impact on human health

and the environment, including the alternative of doing nothing.

4. Full Cost Accounting: When evaluating potential alternatives, there is a duty to

consider all the reasonably foreseeable costs, including raw materials,

manufacturing, transportation, use, cleanup, eventual disposal, and health costs even

if such costs are not reflected in the initial price. Short and long-term benefits and

time thresholds should be considered when making decisions.

5. Participatory Decision Process: Decisions applying the Precautionary Principle

must be transparent, participatory, and informed by the best available science and

other relevant information.

Applying the Precautionary Principle to Global Warming

December 12, 2000

The "precautionary principle" says that when an activity may threaten human health or the environment,

precautionary measures should be taken -- even if some cause and effect relations are not established

scientifically.

However, using this principle could increase risks to public health and the environment if it is only applied to

the potential harms, but not the possible consequences of the precautionary measures themselves.

For instance, requiring developing countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to combat global warming

may retard economic growth, leading to greater hunger, poorer health and higher mortality.

And higher oil and gas prices could increase hunger and delay the switch from solid fuels to more

environmentally benign fuels for heating and cooking.

To ensure that policies do not create greater harm than the harm avoided, say experts, we need some criteria to

evaluate potential threats. Thus,

Threats to human health, especially the threat of death, should take precedence over threats to the

environment.

More immediate threats should be given priority over threats that could occur later.

Threats of harm that have a higher certainty should take precedence over those that are less certain.

For threats that are equally certain, more weight should be given to those that have a higher expected cost --

which might be measured in expected deaths or lost biodiversity, for instance.

If the technology is available to adapt to the adverse consequences of a policy, the harm can be discounted to

that extent.

Irreversible or persistent potential harms should be given greater priority over temporary or reversible ones.

When applied to global warming, these criteria indicate we should focus on solving current problems that may

be aggravated by climate change, and on increasing society's adaptability and decreasing its vulnerability to

environmental problems.

Source: Indur M. Goklany, "Applying the Precautionary Principle to Global Warming," Policy Study Number

158, November 2000, Center for the Study of American Business, Washington University, Campus Box 1027,

One Brookings Drive, St. Louis, Mo., 63130, (314) 935-5630.

You might also like

- Remedials 2021 All AssignmentsDocument2 pagesRemedials 2021 All AssignmentsJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- GMOs EcoWatch July 2021Document7 pagesGMOs EcoWatch July 2021John OsborneNo ratings yet

- 8vo Science Supletorio ProjectDocument3 pages8vo Science Supletorio ProjectJohn Osborne0% (1)

- Rubric Timeline Cell TheoryDocument1 pageRubric Timeline Cell TheoryJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- How To Make In-Text CitationsDocument15 pagesHow To Make In-Text CitationsJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Writing The Title For Your ThesisDocument2 pagesWriting The Title For Your ThesisJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- 8th Grade Q2 Project June 2021Document3 pages8th Grade Q2 Project June 2021John Osborne33% (3)

- Writing Your AbstractDocument2 pagesWriting Your AbstractJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Peppered Moth PowerPointDocument12 pagesPeppered Moth PowerPointJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Title Page Template For ThesisDocument1 pageTitle Page Template For ThesisJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Writing The AbstractDocument10 pagesWriting The AbstractJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Writing Your AbstractDocument2 pagesWriting Your AbstractJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Chemistry in BiologyDocument15 pagesChemistry in BiologyJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Guide To Preparing and Writing The Final DissertationDocument5 pagesGuide To Preparing and Writing The Final DissertationJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Calendar Tesis de GradoDocument4 pagesCalendar Tesis de GradoJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Role of SupervisorsDocument1 pageRole of SupervisorsJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Structure of The Tesis de Grado in ScienceDocument5 pagesStructure of The Tesis de Grado in ScienceJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Details of Assessment Tesis de Grado in ScienceDocument5 pagesDetails of Assessment Tesis de Grado in ScienceJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTION To CHEMISTRYDocument19 pagesINTRODUCTION To CHEMISTRYJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Living ThingsDocument11 pagesCharacteristics of Living ThingsJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Plan of Action For Science ProjectDocument3 pagesPlan of Action For Science ProjectJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Guide To Preparing and Writing The Final DissertationDocument5 pagesGuide To Preparing and Writing The Final DissertationJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Bonding Questions Class WorkDocument13 pagesBonding Questions Class WorkJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Chemical BondingDocument13 pagesChemical BondingJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Introduction To ORGANIC Chemical CompoundsDocument20 pagesIntroduction To ORGANIC Chemical CompoundsJohn Osborne50% (2)

- Regulations For Participants and Supervisors in The Virtual Science Fair 2021Document1 pageRegulations For Participants and Supervisors in The Virtual Science Fair 2021John OsborneNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Organic ChemistryDocument17 pagesIntroduction To Organic ChemistryJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Guide BookletDocument12 pagesGuide BookletJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Science ExperimentsDocument113 pagesScience Experimentsdashmahendra123100% (3)

- A Template For PlanningDocument2 pagesA Template For PlanningJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Impact of Bap and Iaa in Various Media Concentrations and Growth Analysis of Eucalyptus CamaldulensisDocument5 pagesImpact of Bap and Iaa in Various Media Concentrations and Growth Analysis of Eucalyptus CamaldulensisInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Rhodes Motion For Judicial NoticeDocument493 pagesRhodes Motion For Judicial Noticewolf woodNo ratings yet

- Cells in The Urine SedimentDocument3 pagesCells in The Urine SedimentTaufan LutfiNo ratings yet

- Irctc Tour May 2023Document6 pagesIrctc Tour May 2023Mysa ChakrapaniNo ratings yet

- Equipment, Preparation and TerminologyDocument4 pagesEquipment, Preparation and TerminologyHeidi SeversonNo ratings yet

- 2016 Mustang WiringDocument9 pages2016 Mustang WiringRuben TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Antiquity: Middle AgesDocument6 pagesAntiquity: Middle AgesPABLO DIAZNo ratings yet

- Testbanks ch24Document12 pagesTestbanks ch24Hassan ArafatNo ratings yet

- Basic Five Creative ArtsDocument4 pagesBasic Five Creative Artsprincedonkor177No ratings yet

- The Sound Collector - The Prepared Piano of John CageDocument12 pagesThe Sound Collector - The Prepared Piano of John CageLuigie VazquezNo ratings yet

- Clean Agent ComparisonDocument9 pagesClean Agent ComparisonJohn ANo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: The Critical Role of Classroom Management DescriptionDocument2 pagesChapter 1: The Critical Role of Classroom Management DescriptionJoyce Ann May BautistaNo ratings yet

- Identifying The TopicDocument2 pagesIdentifying The TopicrioNo ratings yet

- Active and Passive Voice of Future Continuous Tense - Passive Voice Tips-1Document5 pagesActive and Passive Voice of Future Continuous Tense - Passive Voice Tips-1Kamal deep singh SinghNo ratings yet

- Investigatory Project Pesticide From RadishDocument4 pagesInvestigatory Project Pesticide From Radishmax314100% (1)

- Artificial IseminationDocument6 pagesArtificial IseminationHafiz Muhammad Zain-Ul AbedinNo ratings yet

- Practice Like-Love - Hate and PronounsDocument3 pagesPractice Like-Love - Hate and PronounsangelinarojascnNo ratings yet

- MSDS FluorouracilDocument3 pagesMSDS FluorouracilRita NascimentoNo ratings yet

- PWC Global Project Management Report SmallDocument40 pagesPWC Global Project Management Report SmallDaniel MoraNo ratings yet

- Political Reporting:: Political Reporting in Journalism Is A Branch of Journalism, Which SpecificallyDocument6 pagesPolitical Reporting:: Political Reporting in Journalism Is A Branch of Journalism, Which SpecificallyParth MehtaNo ratings yet

- VL2019201000534 DaDocument2 pagesVL2019201000534 DaEnjoy LifeNo ratings yet

- Understanding Oscilloscope BasicsDocument29 pagesUnderstanding Oscilloscope BasicsRidima AhmedNo ratings yet

- Obligations and Contracts Bar Questions and Answers PhilippinesDocument3 pagesObligations and Contracts Bar Questions and Answers PhilippinesPearl Aude33% (3)

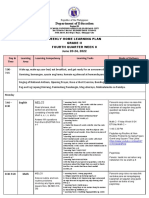

- Department of Education: Weekly Home Learning Plan Grade Ii Fourth Quarter Week 8Document8 pagesDepartment of Education: Weekly Home Learning Plan Grade Ii Fourth Quarter Week 8Evelyn DEL ROSARIONo ratings yet

- Socially Responsible CompaniesDocument2 pagesSocially Responsible CompaniesItzman SánchezNo ratings yet

- Master of Commerce: 1 YearDocument8 pagesMaster of Commerce: 1 YearAston Rahul PintoNo ratings yet

- Impolitic Art Sparks Debate Over Societal ValuesDocument10 pagesImpolitic Art Sparks Debate Over Societal ValuesCarine KmrNo ratings yet

- Reservoir Rock TypingDocument56 pagesReservoir Rock TypingAffan HasanNo ratings yet

- Expressive Matter Vendor FaqDocument14 pagesExpressive Matter Vendor FaqRobert LedermanNo ratings yet

- Positioning for competitive advantageDocument9 pagesPositioning for competitive advantageOnos Bunny BenjaminNo ratings yet