Professional Documents

Culture Documents

EN

Uploaded by

reacharunkOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

EN

Uploaded by

reacharunkCopyright:

Available Formats

Chap. I.: BEAUTY IN ARCHITECTURE.

sr57

BOOK lit.

rilACTICE OF ARCHITECTTIRE.

CHAP. I.

GRECIAN AND ITALIAN AECHITECTLRE.

Sect. I.

BEAUTY IN AIICHITECTUKE.

2192. The existence of architecture as a fine art is dependent on expression, or tlie

faculty of representing, by means of lines, words, or other media, the inventions which the

architect conceives suitable to the end proposed. That end is twofold

; to l)e useful, and

to connect the use with a pleasurable sensation in the spectator of the invention. In

clociuence and poetry the end is to instruct, and such is the object of the higher and histo-

rical classes of painting ; but architecture, though the elder of the arts, cannot claim the

rank due to painting and poetry, albeit its end is so much more useful and necessary to

mankind. In the sciences the end is utility and instruction, but in them the latter is not

of that high moral importance, however useful, which allows them for a moment to come

into competition with the great arts of painting, poetry, and elocjuence. It will be seen

that we here make no allusion to the lower branches of portrait and landscape painting,

but to that great moral and religious end which fired the mind of Michael Angelo in the

Sistine Chapel, and of Raffaelle Sanzio in the Stanze of the Vatican and in the Cartoons.

Above the lower branches of painting just mentioned, the art whereof we treat occupies

an exalted station. In it though the chief end is to produce an useful result, yet the ex-

pression on which it depends, in common with the other great arts, brings each within the

scope of those laws which govern generally the fine arts whose object is beauty. Beauty,

whatever difference of oj)inion may exist on the means necessary to produce it, is by all

admitted to be the result of every perfection whereof an object is susceptible, such perfec-

tions being altogether dependent on the agreeable proportions subsistent between the

several parts, and those between the several parts and the whole. The power or faculty of

inventing is called genius. By it the mind is capable of conceiving and of expressing its

conceptions. Taste, which is capable of being acquired, is the natural sensation of a mind

refined by art. It guides genius in discerning, embracing, and producing beauty. Here

we may for a moment pause to inquire what may be considered a standard of taste, and

that cannot be better done than in the words used on the subject by Hume (Essay xxiii. ):

"

The great variety of tastes," says that author,

"

as well as of opinion, which prevails in the

world, is too obvious not to have fallen under every one's observation. Men of the most

confined knowledge are able to remark a difference of taste in the narrow circle of their

acquaintance, even where the persons have been educated under the same government and

have early imbibed the same prejudices. But those who can enlarge their view to con-

template distant nations and remote ages are still more surprised at the great inconsistence

and contrariety. We are apt to call barbarous whatever departs widely fiom our own

taste and apprehension, but soon find the epithet of reproach retorted on us, and the

highest arrogance and self-conceit is at last startled on observing an e(jual assurance on all

sides, and scruples, amidst such a contest of sentiment, to pronounce positively in its own

favour." True as are the observations of this philosopher in respect of a standard of taste,

we shall nevertheless attempt to guide the reader to some notion of a standard of taste in

architecture.

249:5. There has lately grown into use in the arts a silly pedantic term under the name of

Esthetics, founded on the Greek word 'AiffSrjri/cbs, one which means having the power of

perception by means of the senses; said to be the science whereby the first principles in all'

the arts are derived, from the effect which certain combinations have on the mind as con

nccted with nature and reason : it is, however, one of the metaphysical and useless additions

You might also like

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- NameDocument2 pagesNamereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocument65 pagesSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- PZU EDUKACJA INSURANCE TERMSDocument19 pagesPZU EDUKACJA INSURANCE TERMSreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocument65 pagesSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1460)Document1 pageEn (1460)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1461)Document1 pageEn (1461)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1464)Document1 pageEn (1464)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1462)Document1 pageEn (1462)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1463)Document1 pageEn (1463)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Emergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014Document2 pagesEmergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1459)Document1 pageEn (1459)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1458)Document1 pageEn (1458)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocument1 pageMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1390)Document1 pageEn (1390)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1456)Document1 pageEn (1456)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1455)Document1 pageEn (1455)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1387)Document1 pageEn (1387)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1454)Document1 pageEn (1454)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1452)Document1 pageEn (1452)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1457)Document1 pageEn (1457)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1453)Document1 pageEn (1453)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1450)Document1 pageEn (1450)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1389)Document1 pageEn (1389)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1388)Document1 pageEn (1388)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1451)Document1 pageEn (1451)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocument1 pageAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Early Work of Aubrey BeardsleyDocument660 pagesThe Early Work of Aubrey Beardsleydubiluj100% (3)

- English Blue Archive FAQDocument40 pagesEnglish Blue Archive FAQCoass - Sukma Purnama SidhiNo ratings yet

- The City As Project Aureli - Preface - IntroDocument16 pagesThe City As Project Aureli - Preface - Introlou CypherNo ratings yet

- Comparative Analysis: - The Starry Night, 1889 by Vincent Van GoghDocument7 pagesComparative Analysis: - The Starry Night, 1889 by Vincent Van Goghlilas tinawiNo ratings yet

- Eleanor Shaw CV 2019Document1 pageEleanor Shaw CV 2019Eleanor ShawNo ratings yet

- RemazollevafixprocionDocument22 pagesRemazollevafixprocionkhairraj67% (3)

- High Tech ArchitectureDocument34 pagesHigh Tech ArchitectureRidhuGahalotRdgNo ratings yet

- Ameerpet (Imperial Towers) Interior Works TenderDocument4 pagesAmeerpet (Imperial Towers) Interior Works Tenderyamanta_rajNo ratings yet

- Grand Hotel: Redesigning Modern LifeDocument8 pagesGrand Hotel: Redesigning Modern LifestefanNo ratings yet

- The Barriers: From Combat To DanceDocument17 pagesThe Barriers: From Combat To DanceJon GillinNo ratings yet

- InstallationManualDocument6 pagesInstallationManualErnest IpNo ratings yet

- Complete Kicking The Ultimate Guide To Kicks For Martial Arts Self-Defense & Combat SportsDocument140 pagesComplete Kicking The Ultimate Guide To Kicks For Martial Arts Self-Defense & Combat SportsXenthoyo Kenth Lee100% (8)

- Digital Creativity Published Article PDFDocument19 pagesDigital Creativity Published Article PDFanaNo ratings yet

- Bupena Bhs Inggris Kelas XDocument40 pagesBupena Bhs Inggris Kelas Xkokotopnemen73% (11)

- General Motors Regular Production Options (Rpo) CodesDocument58 pagesGeneral Motors Regular Production Options (Rpo) CodeskallekuhlaNo ratings yet

- Checksheet Mixing PaintDocument1 pageChecksheet Mixing PaintRizqy Fadry LazimNo ratings yet

- Ngo Cho Bible Preview PDFDocument32 pagesNgo Cho Bible Preview PDFdiamond6875% (4)

- AnswerDocument12 pagesAnswerវិសុទ្ធ រតនសម្បត្តិNo ratings yet

- BJRK - All Is Full of LoveDocument9 pagesBJRK - All Is Full of LoveSylwia DrwalNo ratings yet

- IDSC Art Appreciation Course SyllabusDocument9 pagesIDSC Art Appreciation Course SyllabusJellane SeletariaNo ratings yet

- Martinez-A Semiotic Theory MusicDocument6 pagesMartinez-A Semiotic Theory MusicAnonymous Cf1sgnntBJ100% (1)

- Brooklyn Museum Brooklyn Museum Bulletin: This Content Downloaded From 195.43.22.135 On Sun, 23 Sep 2018 20:01:43 UTCDocument17 pagesBrooklyn Museum Brooklyn Museum Bulletin: This Content Downloaded From 195.43.22.135 On Sun, 23 Sep 2018 20:01:43 UTCNosoNo ratings yet

- Lars Von TrierDocument9 pagesLars Von Triermaretxu12No ratings yet

- Matilda Study GuideDocument18 pagesMatilda Study GuideEd100% (2)

- Choose the correct answerDocument1 pageChoose the correct answerIoana Mihaela Ioana MihaelaNo ratings yet

- G4 - (HELE) 4TH Periodical Exam S.Y 2022-2023Document2 pagesG4 - (HELE) 4TH Periodical Exam S.Y 2022-2023moneth gerarmanNo ratings yet

- Zaha Hadid's groundbreaking architectureDocument26 pagesZaha Hadid's groundbreaking architectureAna NiculescuNo ratings yet

- Customer ListDocument4 pagesCustomer ListMir Md Mizanur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Architectural drawing list template for ICC projectDocument2 pagesArchitectural drawing list template for ICC projectPERVEZ AHMAD KHANNo ratings yet

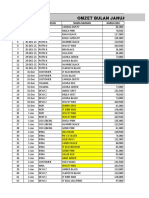

- Omzet 2022Document177 pagesOmzet 2022Topi Jerami StudioNo ratings yet