Professional Documents

Culture Documents

THE STATE V

Uploaded by

KirbyJoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

THE STATE V

Uploaded by

KirbyJoCopyright:

Available Formats

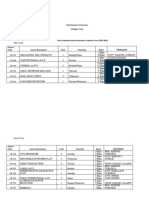

THE STATE v.

RAMDIAL ET AL

Add to List

icon

Citation # TT 2006 HC 55

Country Trinidad and Tobago

Court High Court

Judge Mohammed, J.

Subject Criminal practice and procedure

Date July 11, 2006

Suit No. Cr. No. 117 of 2004

Subsubject Right to reply Closing arguments - Whether the prosecutor had the

right to reply where the defence did not make closing arguments Prosecutor's

right to reply was not contingent upon exercise of defence Right of reply was

dependent only on whether witnesses had been adduced in support of the defence

Right of reply was discretionary.

Full Text Appearances:

Mr. I. Khan, S.C., Mrs. K. Waterman-Latchoo and Ms. T. Hudlin for the State.

Mrs. P. Elder S.C., and Mr. O. Hinds for Devindra Ramdial.

Mr. G. Peterson S.C., and Ms. A. Francis for Ansen Griffith.

MOHAMMED, J.: Section 39 of the Criminal Procedure Act, Chapter 12:02

provides, that the accused person or his counsel shall be allowed, if he thinks fit, to

open his case and after the conclusion of such opening, the accused person or his

counsel shall be entitled to adduce evidence in support of the defence and when all

the evidence is concluded, to sum up the evidence. (End of page 1)

Section 40 of that Act goes on to provide that the counsel for the Prosecution shall,

in all cases, have the right of reply. Section 15, subsection 2 of the Evidence Act,

Chapter 7:02 provides that in cases where the right of reply depends upon the

question whether evidence has been called for the defence, the fact that the person

charged has been called as a witness, shall not of itself confer on the Prosecution

the right of reply.

In this case, Accused No. 1 has elected not to give evidence but has called three

witnesses, one of those witnesses being as to character. Accused No. 2 has given

evidence and has called on his behalf two witnesses. One of the witnesses called on

behalf of the second named accused is Professor Hubert Daisley whose evidence is

relevant to the cases of both Accused.

Counsel for both Accused No. 1 and No. 2 have intimated that they propose not to

make closing addresses to the jury. Counsel for the State, Mr. Khan, has applied to

make a closing address to the jury. As observed by former Chief Justice de la

Bastide in the Court of Appeal judgment in Allie Mohammed v. the State, 1996,

Volume 51 W.I.R., page 320, at page 324 letter "d", there is an apparent conflict

between Section 40 of the Criminal Procedure Act and Section 15, subsection 2 of

the Evidence Act.

The relevant provisions in Guyana are identical to those in Trinidad. Under the

Guyana Criminal Law (Procedure) Act, sections 148 and 149 are of the same

content and appear in the same order as sections 39 and 40 of the Trinidad and

Tobago Criminal Procedure Act. (End of page 2)

In the case of DPP's Reference, (No. 1 of 1980) Vol. 29 W.I.R. at page 94, a

Submission of No Case to Answer at the end of the Prosecution's evidence had

been overruled. There has been certain weaknesses in the State's identification

evidence. The accused made an unsworn statement from the dock and he called no

witness. Defence counsel declined in that case to address the jury. State counsel

had then applied to address the jury claiming that he had a right of reply. The trial

judge ruled that he did not.

The Court of Appeal of Guyana, after a careful and thorough review of this point,

concluded within the factual context of that case as follows, and I will set out

various conclusions as I have been able to cull them from that case:

(1) That insofar as the trial judge had categorically ruled that the State did not have

a right of reply in the circumstances, he was wrong;

(2) That the prosecution had a statutorily conferred right of reply in all cases which

means exactly what it says;

(3) That while those words give and are intended to give counsel the right of reply,

that is, the power to reply in all cases, prosecuting counsel should not do so in

every case;

(4) The right conferred on counsel for the prosecution is not of an obligatory nature

but rather of a discretionary nature and it is in turn subject to the overriding

discretion of the trial judge to control excesses and possible abuse of discretionary

power and privileges; (End of page 3)

(5) Further, that the circumstances must be sufficient enough to warrant an exercise

of the power. Relevant questions were, did the interests of justice make it

necessary that counsel for the State should wish to reply and, did the interests of

justice make it compelling that he should do so;

(6) Further, the Court of Appeal decided in the DPP's Reference (No. 1 Of 1980)

that the interests of justice in that case could not have made it necessary that

counsel for the State should have wished to reply, where the identification

evidence was "palpably weak".

The Court of Appeal observed that the trial judge might well have removed the

case from the jury because of particular difficulties with respect to the visual

identification evidence. The Court of Appeal of Guyana was of the view that by

claiming the right of reply, an obvious attempt was being made on the part of the

prosecutor in that case, to bolster up a weak prima facie case.

In that case, apart from the unsworn statement of the accused, the accused did not

call any witnesses to substantiate it. At page 112, letter "j" and pg. 113, letter "a" of

the Judgment, Chancellor Crane said:

"But apart from his unsworn statement, he did not call any witnesses to

substantiate it. It would have been otherwise, I think, if he had called witnesses in

support because that might have been sufficient reason for counsel for the State to

exercise his discretionary right of reply." (End of page 4)

The facts of the locus classicus on this point in this jurisdiction, that is the case of

Allie Mohammed, are different in my view. There the accused alone had given

evidence. By the operation of section 15(2) of the Evidence Act, that by itself did

not confer upon the Prosecution the right of reply. Additionally, no closing address

had been made by defence counsel. It was plain, in those circumstances therefore,

that the prosecuting counsel had no right of reply under section 15 subsection 2 of

the Evidence Act, the accused alone having given evidence. The learned judge was

therefore wrong to have allowed him to make a closing speech and the error was

compounded by the inappropriate and unbecoming style of the prosecutor's closing

address.

A question has arisen during the course of the arguments in the case at Bar as to

whether, by practice in this jurisdiction, the prosecutor's right of reply is contingent

or partly contingent upon whether or not the defence makes a closing address.

Bearing this question in mind, the following paragraph from the judgment of

former Chief Justice de la Bastide in Allie Mohammed v. The State at pg. 325

letter "c" needs to be examined:

"The right given by section 40 is a right of reply in circumstances like these where

there is no address by or on behalf of the accused and no witnesses called by him.

There is nothing for the prosecution to reply to, save and except his own testimony.

To permit a reply by the prosecution, in those circumstances, would fly in the teeth

of section 15 subsection 2. There is no doubt that that is the section which deals

specifically with the situation that arose in this case and, in our view it should

therefore be regarded as the governing provision." (End of page 5)

While this paragraph appears, at first blush, to recognise that the making of a

closing address by defence counsel is a relevant factor to be taken into account in

determining whether the prosecutor has a right of reply, when the paragraph is

properly read, it seems clear that the conclusion was based on the prosecution's

purported exercise of the right of reply "flying in the teeth" of section 15,

subsection 2 of the Evidence Act, as former Chief Justice de la Bastide termed it.

No doubt the fact that the Defence counsel made no closing address may have been

a compounding or an exacerbating factor, but on a proper reading of Allie

Mohammed the decision really turned on section 15 subsection 2 of the Evidence

Act and nothing else.

In Allie Mohammed the Court of Appeal of Trinidad and Tobago followed DPP's

Reference (No. 1 of 1980) of Guyana. In Guyana, as I have already observed, the

relevant provisions are identical to those in Trinidad. Section 54 of the Guyanese

Evidence Act is identical to section 15, subsection 2 of the Trinidad and Tobago

Evidence Act. Sections 148 and 149 of the Guyana Criminal (Procedure) Act are

identical in content and sequence to sections 39 and 40 of the Trinidad and Tobago

Criminal Procedure Act, Chapter 12:02.

In DPP's Reference (No. 1 of 1980), the accused had made an unsworn statement

from the dock and the defence counsel had not addressed the jury yet, Chancellor

Crane was of the view that if witnesses had been called in support, there might

have been sufficient reason for counsel for the State to exercise his discretionary

right of reply see page 112, letter "j" and page 113, letter "a" of that judgment. This

suggests that whether or not the defence decides to make a closing speech is not a

relevant legal consideration in determining whether the (End of page 6) State has a

right of reply.

It is necessary to examine three other parts of the decision of the Court of Appeal

of Guyana in DPP's Reference (No. 1 of 1980). Chancellor Crane, at page 109 of

the judgment, letter "a", referred to the position in England prior to the introduction

of the English Criminal Procedure (Right of Reply) Act of 1964:

"In England, prior to the Criminal Procedure (Right of Reply) Act, 1964, the order

of the closing speeches used to be as follows: if the defence called any witnesses

other than the accused or witnesses to character only, the prosecution had a right of

reply whether or not the defence made a closing speech. If this right was exercised,

the speech was made after the closing speech for the defence, if any."

In answering the reference, Chancellor Crane concluded at pg. 113, letter "e":

"Failure of defence counsel to sum up on all the evidence cannot deprive counsel

for the State of his right to reply because, quite apart from any unworn statement,

the right to reply has from very ancient times been [DEPENDENT ONLY ON

WHETHER WITNESSES HAVE BEEN ADDUCED IN SUPPORT OF THE

DEFENCE] [Emphasis added], save after 1900 when the accused alone gives

evidence, that fact will not by itself entitle the prosecution to reply (see s 54 of the

Evidence Act)." (emphasis mine) (End of page 7)

At page 121, letters "b" to "e", Justice of Appeal Luckhoo said:

"I find myself unable to accede to the argument that because the right of reply was

denied the Prosecution in a situation to which Section 54 of the Evidence Act

applied, the position since 1900 would have to be reviewed and that the Court

should hold that, a fortiori, there was no right of reply where only an unsworn

statement was made without witnesses being called for the Defence and without an

address being made to the jury on behalf of the Defence. [IT MUST BE

REMEMBERED THAT THE RIGHT OF REPLY IS A STATUTORY,

SUBSTANTIVE RIGHT, ALBEIT SECRETED IN THE INTERSTICES OF

PROCEDURE, AND THAT THE QUALIFICATION CONTAINED IN

SECTION 54 OF THE EVIDENCE ACT WAS EXPRESSLY LIMITED TO THE

SITUATION THERE PROVIDED FOR. ANY FURTHER RESTRICTION OR

QUALIFICATION OF THAT RIGHT WOULD BE MATTER FOR

PARLIAMENT'S ATTENTION, NOT THE COURT'S. THE NON-EXERCISE

BY THE DEFENCE OF THEIR RIGHTS UNDER THE PROVISIONS OF

SECTION 148 OF THE CRIMINAL LAW (PROCEDURE) ACT, FOR

EXAMPLE, THE WAIVER OF THE RIGHT TO OPEN THE CASE FOR THE

DEFENCE OR, IN ANY WAY TO ADDUCE EVIDENCE OR, TO SUM UP

WAS NO BAR TO THE EXERCISE BY COUNSEL FOR THE PROSECUTION

OF HIS RIGHT OF REPLY UNDER SECTION 149. THE ENJOYMENT OF

THE LATTER, SAVE IN THE ONE INSTANCE NOTED, WAS NOT TO BE

CONSTRUED AS BEING CONTINGENT UPON THE EXERCISE OF ALL OR

ANY OF THE DEFENCE RIGHTS]." (emphasis mine)

Applying these principles, I am of the respectful view that the position in this

jurisdiction and in this particular case is as follows:

(1) The exercise of the prosecution's right of reply is not contingent upon the

exercise by (End of page 8) the defence of their option to deliver a closing address.

Insofar as this has been assumed to be the "procedural law" in this jurisdiction, I

say with great respect, that his assumed position does not appear to be properly

founded in law. The right of reply is dependent only on whether witnesses have

been adduced in support of the defence;

(2) The right of reply is not of procedural nature as is frequently assumed, but is a

substantive, statutory right, as described by Justice of Appeal Luckhoo in DPP's

Reference (No. 1 of 1980) and it is subject only to the limitation contained in

section 15, subsection 2 of the Evidence Act. Any further restriction or

qualification would be a matter for Parliament and not the Courts;

(3) The case of Allie Mohammed turned on section 15, subsection 2 of the

Evidence Act, the accused alone having given evidence in that case. Allie

Mohammed properly read, is not support for the proposition that the prosecutor's

right of reply is contingent or partly contingent upon whether the defence makes a

closing address. In any event, the facts of Allie Mohammed are distinguishable

from those of the case at Bar;

(4) In a case such as this, where in both cases the accused have called witnesses

and the defence intends not to address, in my view, the Prosecution have a

statutorily conferred right of reply;

(5) That right of reply is however not obligatory but rather discretionary;

(6) It is moreover subject to the Court's overriding discretion to control possible

abuses (End of page 9) and excesses of discretionary power and privileges.

(7) In exercising this supervisory discretion, relevant questions, to my mind are, as

postulated in DPP's Reference (No. 1 of 1980), do the interests of justice make it

necessary that the State should wish to reply, and do the interests of justice make it

compelling that the State should wish to do so? In answering these questions I do

not consider it appropriate to factor into account that the defence have made quite

detailed opening arguments. The law in this regard is clear, and I refer to Archbold

Criminal Practice 2006, paragraph 4-310:

"Where the rights exists, counsel for the defendant is entitled to open his case fully

to the jury; this includes not only outlining the defence's case, but also criticising

the prosecution's evidence, see R v. Randall, the Times, July 11, 1973, United

Kingdom Court of Appeal."

Accordingly, I do not think that it is appropriate to factor this into account. In an

opening address for the defence, the defence is entitled to criticise the prosecution's

evidence. The main question, as I see it, is this: is the prosecutor seeking to address

for any apparent oblique motive such as was the case in DPP's Reference (No. 1 of

1980), to prop up a palpably weak prima facie case?

While in this case there are potential weaknesses in Barrymoore Briggs' evidence, I

do not think, respectfully, that the prosecution's case can be properly characterised

as palpably weak. It must be borne in mind that this is almost purely a credibility

case and, therefore, everything turns, at the end of the day, on what the jury makes

of the witness. As much as (End of page 10) there may be factors potentially

adverse to Briggs's credibility, there may as well be potential factors in favour of it.

I therefore am unable to conclude that there is any oblique motive on the part of

the prosecutor in seeking to exercise the right of reply. This being a credibility

case, where there are factors which speak both possibly against and in favour of

Briggs' credibility in the context of all the evidence on all sides of the case, I think

that the interests of justice make it necessary that the State should wish to reply.

The circumstances are sufficient enough to reasonably warrant, in my respectful

view, the prosecution's exercise of its discretionary statutory right.

This is therefore an appropriate case for the State to seek to rely on its

discretionary right of reply. (End of page 11)

New search | Revise Search | Back to search results | First | Previous | Next | Last

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Vivian Clarke V The StateDocument32 pagesVivian Clarke V The StateKirbyJo100% (1)

- Injunction To Restrain - American CyanamidDocument1 pageInjunction To Restrain - American CyanamidKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Benjamin v. The StateDocument9 pagesBenjamin v. The StateKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Funrose v. AgDocument4 pagesFunrose v. AgKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- CIVIL PROCEDURE AND PRACTICE IIDocument12 pagesCIVIL PROCEDURE AND PRACTICE IIKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Spanish Grammar!!!!!!!Document47 pagesSpanish Grammar!!!!!!!Keshiya Renganathan100% (11)

- Double Recovery Canadian CaseDocument20 pagesDouble Recovery Canadian CaseKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- 1943 Prison RulesDocument45 pages1943 Prison RulesKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Aventura 1 WorkbookDocument201 pagesAventura 1 WorkbookKirbyJo73% (11)

- Registration Process Chart For SpanioshDocument1 pageRegistration Process Chart For SpanioshKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Fitness Template Revised April 2015Document4 pagesCertificate of Fitness Template Revised April 2015KirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Henry Greene V DPPDocument25 pagesHenry Greene V DPPKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Carole Mortimer's Romance Novel ListDocument8 pagesCarole Mortimer's Romance Novel ListKirbyJo0% (1)

- Issue and Service of ProceedingsDocument7 pagesIssue and Service of ProceedingsKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Hussey V Eels (1990) 2 QB 227, (1990) 1 AllDocument2 pagesHussey V Eels (1990) 2 QB 227, (1990) 1 AllKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- 1A1 - The Traditional and The Modern AttorneyDocument5 pages1A1 - The Traditional and The Modern AttorneyKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Timetable Supplementary Exam August 2014 HWLSDocument1 pageTimetable Supplementary Exam August 2014 HWLSKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- 1A - Remedies in The Arsenal of The Modern LawyerDocument2 pages1A - Remedies in The Arsenal of The Modern LawyerKirbyJoNo ratings yet

- Part PerformanceDocument3 pagesPart PerformanceKirbyJo67% (9)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Wills and Succession Case Digest CanedaDocument2 pagesWills and Succession Case Digest CanedaJacob CastroNo ratings yet

- Ungria Vs CA DigestDocument1 pageUngria Vs CA DigestAziel Marie C. GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Pierce V CarltonDocument1 pagePierce V Carltonrgtan3No ratings yet

- Melendres # 675 - MCSO Proposed Training ScheduleDocument29 pagesMelendres # 675 - MCSO Proposed Training ScheduleJack RyanNo ratings yet

- Estate Planning Intake FormDocument8 pagesEstate Planning Intake Formbash shangNo ratings yet

- Aratuc Vs ComelecDocument19 pagesAratuc Vs ComelecKyle JamiliNo ratings yet

- Meaning of FreedomDocument2 pagesMeaning of FreedomMelody B. MiguelNo ratings yet

- Midterm, Irene BernandineDocument13 pagesMidterm, Irene BernandineIrene BernandineNo ratings yet

- Dr Batiquin Liability for Rubber Glove Piece in PatientDocument1 pageDr Batiquin Liability for Rubber Glove Piece in PatientLang Banac LimoconNo ratings yet

- CREDIT CARD DEBT AND BANK LOAN OBLIGATIONSDocument21 pagesCREDIT CARD DEBT AND BANK LOAN OBLIGATIONScris100% (3)

- Uy Vs Zamora PDFDocument5 pagesUy Vs Zamora PDFdominicci2026100% (1)

- Karan Vs State of HaryanaDocument73 pagesKaran Vs State of HaryanaRuhani Mount CarmelNo ratings yet

- Brockton Police Log March 18Document20 pagesBrockton Police Log March 18BBNo ratings yet

- United States v. Legarda, 17 F.3d 496, 1st Cir. (1994)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Legarda, 17 F.3d 496, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- North Sea Continental Shelf Cases Germany v. Denmark - HollandDocument2 pagesNorth Sea Continental Shelf Cases Germany v. Denmark - HollandSecret SecretNo ratings yet

- Sppulaw Question BankDocument82 pagesSppulaw Question Banksony dakshuNo ratings yet

- Victoria v. COMELEC Rules on Ranking Sanggunian MembersDocument4 pagesVictoria v. COMELEC Rules on Ranking Sanggunian MembersChristian Villar0% (1)

- Estate TaxDocument8 pagesEstate TaxAngel Alejo AcobaNo ratings yet

- Ware vs Hylton Case on International LawDocument479 pagesWare vs Hylton Case on International LawMaria Margaret MacasaetNo ratings yet

- Executed ContractDocument3 pagesExecuted Contractchecha locaNo ratings yet

- Trust Document ExampleDocument5 pagesTrust Document ExampleRed Moon EssentialsNo ratings yet

- Northwestern University College of LawDocument5 pagesNorthwestern University College of LawNorma ArquilloNo ratings yet

- Municipality of Famy v. Municipality of SiniloanDocument14 pagesMunicipality of Famy v. Municipality of SiniloanAaron James PuasoNo ratings yet

- Kawasaki Port Service Corporation vs. AmoresDocument10 pagesKawasaki Port Service Corporation vs. AmoresHariette Kim TiongsonNo ratings yet

- Assignment Subject: Law of Taxation TOPIC: "Advocates Welfare Act, 2001"Document7 pagesAssignment Subject: Law of Taxation TOPIC: "Advocates Welfare Act, 2001"Rajput ShobhitNo ratings yet

- The 1988 Constitutional Crisis in MalaysiaDocument26 pagesThe 1988 Constitutional Crisis in MalaysiaJiaqi WongNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law Group Assignment InsightsDocument10 pagesAdministrative Law Group Assignment InsightsRANDAN SADIQNo ratings yet

- Outline Land Registration and Torrens System 2Document24 pagesOutline Land Registration and Torrens System 2Ralph Jaramillo100% (1)

- CJ Critical Thinking - Gun Control 1Document9 pagesCJ Critical Thinking - Gun Control 1api-510706791No ratings yet

- Amity National Moot Court CompetitionDocument3 pagesAmity National Moot Court CompetitionMohd AqibNo ratings yet