Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alekhine - Chess

Uploaded by

pionier73Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alekhine - Chess

Uploaded by

pionier73Copyright:

Available Formats

Lasker Plagiarises the Great Morphy

In these lectures, in this book, Lasker plagiarised the great Morphy and his ideas about the

fight for the centre and about attack in and for itself. For the idea of attack as

something optimistic, something creative, was entirely unfamiliar to Lasker the chess

master and in this regard he was the natural successor to Steinit, the greatest grotes!ue

the history of chess had to endure.

What is Jewish Chess, the Jewish chess idea in its real essence? It is

not hard to answer this question:-

1. Material profit at all costs

!. "pportunis# - an opportunis# pushed to the hi$hest point with the ai# of

eli#inatin$ e%en the shadow of a potential dan$er and which consequentl& re%eals an idea 'if

one can appl& the word (idea) to this* na#el& (defence, in and for itself.) +s far as future

possibilities are concerned, Jewish chess has du$ its own $ra%e in de%elopin$ this (idea) which,

in an& for# of co#bat whate%er cannot #ean an&thin$ else, finall& than suicide. ,or by merely

defending one"s self, one may occasionally #and how often$% avoid defeat & but how does

one win$ 'here is a possible answer( by a mistake on one"s opponent"s part. )hat if the

opponent fails to make this mistake$ *ll that the defender&at&all&costs can then do is whine

in complaint of this absence of errors.

+t is not easy to e,plain how the defence idea succeeded in gaining so many adherents. *s

far as -urope is concerned, there came, between the matches La .ourdonnais and

Macdonald /sic&0S1 fought with remarkable enthusiasm and spirit, and the appearances

of *nderssen and Morphy, a very characteristic period of chess chess dawn &

culminating probably in the match between Staunton and Saint&*mant.

2ndoubtedly, there are a few true and correct elements in 3iemtsovitch"s doctrines4 but

whatever is correct is no his own but was created by others, old masters as well as

contemporaries, and he plagiarised it, consciously or unconsciously.

Correct were

5. 'he idea of battle for the centre, a Morphy conception4 this had

previously been illustrated by 'chigorin"s best achievements as well as

the games of 6illsbury and 7harousek.

8.and 9. 'he truths of M. de la 6alisse, namely that it is of advantage to occupy the

seventh rank and, finally that it is better to be able to take advantage of two weaknesses in

the opponent"s camp than only one.

'hese were truths. :n the other hand, there were many inaccuracies which were a direct

conse!uence of his attitude toward chess, for whatever was half&way to being original had

a cadaverous smell denying all that is creative. -,amples( #5% manoeuvring is nothing

more than the Steinit&Lasker idea of waiting until one"s opponent blunders4 #8%

overprotection #a premature protection of supposedly weak points% is again a purely

;ewish idea contradicting the whole spirit of struggle, i.e., being afraid of battle. <oubt in

one"s own spiritual powers & truly, this is a sad picture of intellectual self&humiliation=

'o the .ratislava master, >ichard >eti, the chess world owes, without a doubt, gratitude

for having proved the 3iemtsovitch idea of overprotection to be an absurdity. For he

applied the theory of concentrating on an opponent"s weaknesses from the very beginning,

no matter how that opponent built up his game..

>eti was applauded by the plurality of *nglo&;ewish intellectuals for his work Modern

+deas in 7hess, ?ust as 3iemtsovitch had been for My System, and these people were

particularly impressed by the absurd cry >eti invented, namely )e, the young masters

#he was then 9@% are not interested in rules but in e,ceptions. +f this sentence makes

sense at all, it means )e #or rather, +% know the rules governing the game of chess much

too well. 'o carry on with further research in this field will be, in future, the task of the

more feeble&minded of the chess community. .ut, +, the grandmaster, will devote myself

e,clusively to the more delicate filigree of brilliant e,ceptions, with my own clear

elucidations. 'his cheap bluff, this shameless half&attempt at self&boosting, was swallowed

without a struggle by a chess world already doped by ;ewish ?ournalists, the e,ulting cries

of the ;ews and their friends Long Live >eti and the hyper&modern, neo&romantic chess=

finding an echo far and wide.

'he Soviet chess master .otvinnik owes, in my opinion, even more than

his *merican co&religionist to the influence of the younger >ussian school. +nstinctively

inclined

to safety first, he has slowly become a master who knows how to use the weapons of

aggression. 0ow this occurred, is a curious and typical story( not the idea of attack and , if

necessary, sacrifice, but & however, parado,ical this might seem & the idea of procuring, by

attacking possibilities, even greater security for himself, is responsible for this change.

:nly by subtle knowledge, by intensely careful study of #a% new potentialities in the

openings and #b% the attacking and sacrificial techni!ue of the old masters, .otvinnik has

succeeded in rounding off his original style and impressing it with the marks of a certain

many&sidedness. 'hat he is strong, very strong now, there can be no doubt. *ll the same,

most of .otvinnik"s games make a dry and soulless impression. 'his is easily e,plained(

there is no art in which the most perfect copy could arouse the same feelings as the original

and, as far as attack is concerned, .otvinnik"s chess is ?ust no more than an e,cellent copy

of the old masters. +n spite of these shortcomings, + should say that one can consider

.otvinnik to be an e,ception, compared with all the others we have mentioned.

0ailed as a kind of child&prodigy in his hometown #he won the championship of 7uba at

the age of twelve%, admired as a fiery attacking player with real Morphy insight at the

outset of his career, 7apablanca would have become not only the god of the Latin chess

world & as he actually was for long & but the idol of the whole world chess community, had

he not been sent, as a young man, to 7olumbia 2niversity in 3ew Aork and there

assimilated, in ;ewry"s capital, the professional methods of the chess&Aankees. >epressing

his tactical endowments, he forced himself, even as an eighteen&year&old, to regard chess

not as an end in itself, but as a means of livelihood and to pursue the ;ewish principle of

safety&first to the limit. So great were his natural gifts, that for a certain time he was

able to set himself up as a master of defence4 and so shrewd was he that he sought to

?ustify the negative principle of defensive chess, through pseudostrategical conceptions, in

numerous writings. 7ontinual transitory brilliant e,ceptions, fiery blites, occurred,

even in his world championship matches & sub&conscious reactions of his repressed

temperament.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Play Better Chess - Leonard BardenDocument144 pagesPlay Better Chess - Leonard Bardenpionier7391% (11)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Book of Games Alfonso X 1283Document65 pagesBook of Games Alfonso X 1283A.Skromnitsky100% (1)

- Anthology of Chess CombinationsDocument306 pagesAnthology of Chess CombinationsJames Neo100% (1)

- Great Chess Combinations - Robert Fischer - Russian Chess House - 2013 OcrDocument164 pagesGreat Chess Combinations - Robert Fischer - Russian Chess House - 2013 Ocrfhernandez_109582100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Chess Tactics 5000+ VOL. 1 RAWDocument33 pagesChess Tactics 5000+ VOL. 1 RAWTj Ronz Saguid100% (4)

- Opening For White According To Anand 1.e4 Vol.10Document194 pagesOpening For White According To Anand 1.e4 Vol.10Oscar Luna100% (2)

- Ludek Pachman - The Middlegame in Chess - SCDocument198 pagesLudek Pachman - The Middlegame in Chess - SCpionier73100% (13)

- Origami Bonsai Electronic Magazine Vol 2 Issue 2Document23 pagesOrigami Bonsai Electronic Magazine Vol 2 Issue 2Benjamin Coleman100% (8)

- Its Only Me - Tony Miles PDFDocument146 pagesIts Only Me - Tony Miles PDFJuan Angel Perez GarciaNo ratings yet

- MySystemByJ P MullerDocument118 pagesMySystemByJ P Mullerenjuneer1100% (1)

- The Psychology of Chessplayers OcrDocument87 pagesThe Psychology of Chessplayers Ocrpionier73100% (4)

- Winning With The Petroff - KarpovDocument116 pagesWinning With The Petroff - Karpovpionier73100% (4)

- Works of Damiano Ruy Lopez SalbioDocument416 pagesWorks of Damiano Ruy Lopez Salbiotudoranluciana1No ratings yet

- Dufresne Zukertort Grosses Schach HandbuchDocument852 pagesDufresne Zukertort Grosses Schach Handbuchpionier73No ratings yet

- Dufresne Zukertort Grosses Schach HandbuchDocument852 pagesDufresne Zukertort Grosses Schach Handbuchpionier73No ratings yet

- PE 2 Lesson 6 ChessDocument29 pagesPE 2 Lesson 6 ChessRolando GalloNo ratings yet

- Valtra T121-T191 Parts Manual - Steering SystemDocument19 pagesValtra T121-T191 Parts Manual - Steering SystemJakaNo ratings yet

- The Modern Defence: Cyrus Lakdawala's Unconventional Opening RepertoireDocument22 pagesThe Modern Defence: Cyrus Lakdawala's Unconventional Opening RepertoireSimone Fiorella100% (1)

- 2 - Graveclaw - Interactive MapsDocument8 pages2 - Graveclaw - Interactive MapsWizard Level 1No ratings yet

- The Strategic Challenges of Isolated PawnsDocument12 pagesThe Strategic Challenges of Isolated PawnsJude-lo Aranaydo100% (1)

- 01 Scrierile Parintilor ApostoliciDocument351 pages01 Scrierile Parintilor Apostolicibimbaq100% (1)

- Filocalia Vol.7Document528 pagesFilocalia Vol.7Catalin VoinescuNo ratings yet

- Frère Morphys Games of Chess 1859Document162 pagesFrère Morphys Games of Chess 1859pionier73No ratings yet

- American Chess - Monthly 1860 Vol 4Document405 pagesAmerican Chess - Monthly 1860 Vol 4pionier73No ratings yet

- Habits To Live Past 100 - Lessons From The Blue ZonesDocument4 pagesHabits To Live Past 100 - Lessons From The Blue Zonespionier73No ratings yet

- Bertin The Noble Game of Chess London1735Document96 pagesBertin The Noble Game of Chess London1735pionier73No ratings yet

- Chess WisdomDocument19 pagesChess Wisdompionier73No ratings yet

- Think Like A Strong PlayerDocument4 pagesThink Like A Strong PlayerAmit KotkarNo ratings yet

- Canon Psa540 530cugad enDocument139 pagesCanon Psa540 530cugad enGuldeep Singh KhokharNo ratings yet

- Fischer - Analiza Stilului SauDocument2 pagesFischer - Analiza Stilului Saupionier73No ratings yet

- Example of Chess - Master PlayDocument123 pagesExample of Chess - Master Playpionier73No ratings yet

- A Review of The Chess TournamentDocument31 pagesA Review of The Chess Tournamentpionier73No ratings yet

- Staunton and Warmold The Laws and Practice of Chess 1876Document566 pagesStaunton and Warmold The Laws and Practice of Chess 1876pionier73No ratings yet

- American Chess - Monthly 1860 Vol 4Document405 pagesAmerican Chess - Monthly 1860 Vol 4pionier73No ratings yet

- American Chess - Monthly 1860 Vol 4Document405 pagesAmerican Chess - Monthly 1860 Vol 4pionier73No ratings yet

- The Book of The London International CheDocument307 pagesThe Book of The London International Chepionier73No ratings yet

- The Elements of ChessDocument219 pagesThe Elements of Chesspionier73No ratings yet

- The Chess Congress of 1862Document707 pagesThe Chess Congress of 1862pionier73No ratings yet

- Fine Reuben - Basic Chess EndingsDocument295 pagesFine Reuben - Basic Chess Endingspathik8883% (6)

- Bertin The Noble Game of Chess London1735Document96 pagesBertin The Noble Game of Chess London1735pionier73No ratings yet

- Chess/Tournaments: Types of TournamentDocument5 pagesChess/Tournaments: Types of TournamentOliverNo ratings yet

- Scar Tissue Red HotDocument3 pagesScar Tissue Red Hotnataly condoriNo ratings yet

- Chess Notation For ChildrenDocument4 pagesChess Notation For ChildrenTiffany Knoebel MalloyNo ratings yet

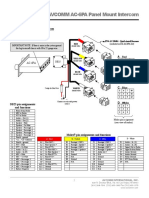

- AC 6PA InstallDocument4 pagesAC 6PA InstallLucio MacielNo ratings yet

- Canadian Chess ProblemsDocument63 pagesCanadian Chess ProblemsNiranjan PrasadNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic User'S Guide: Broadcom Netxtreme Ethernet AdapterDocument171 pagesDiagnostic User'S Guide: Broadcom Netxtreme Ethernet Adapter5290 AgxNo ratings yet

- Corey Congilio 39 S 50 Blues Rhythms You Must Know 1-20Document28 pagesCorey Congilio 39 S 50 Blues Rhythms You Must Know 1-20topotara paluNo ratings yet

- Men's Interzonal Chess Tournament 1990Document148 pagesMen's Interzonal Chess Tournament 1990George_200No ratings yet

- Algorithms For A Minimal Chess PlayerDocument25 pagesAlgorithms For A Minimal Chess PlayerHospodar VibescuNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Microprocessor Lab Report (EM205Document10 pagesIntroduction to Microprocessor Lab Report (EM205Lee Yann LynnNo ratings yet

- ChxbuyDocument27 pagesChxbuyrahulNo ratings yet

- 2005 Mysterion Manual Eng - V2 1 5 1Document61 pages2005 Mysterion Manual Eng - V2 1 5 1Juan Pablo Klinsky100% (1)

- Chess Openings: Queen's Gambit AcceptedDocument2 pagesChess Openings: Queen's Gambit AcceptedTom100% (2)

- Polo Shirt PatternDocument28 pagesPolo Shirt PatternVALLEDOR, Dianne Ces Marie G.No ratings yet

- SchematicDocument25 pagesSchematicMohamed RafiudeenNo ratings yet

- Playing TechniqueDocument4 pagesPlaying TechniquePrasad Aurangabadkar100% (1)

- The 30 Rules of ChessDocument3 pagesThe 30 Rules of ChessMrBlueLakeNo ratings yet

- Davide Rabboni - 100 Mates in 2 (Solutions) - SOLUTIONSDocument1 pageDavide Rabboni - 100 Mates in 2 (Solutions) - SOLUTIONSgaurav_singh_mdNo ratings yet

- Novice Nook: Luck in The Sport of ChessDocument6 pagesNovice Nook: Luck in The Sport of ChessPera PericNo ratings yet