Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration: Author Information

Uploaded by

awuahboh0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views9 pagessdfawsf

Original Title

Present

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentsdfawsf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views9 pagesTranscultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration: Author Information

Uploaded by

awuahbohsdfawsf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

[Articles]

JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration

Issue: Volume 28(11), November 1998, pp 30-38

Copyright: 1998 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Publication Type: [Articles]

ISSN: 0002-0443

Accession: 00005110-199811000-00008

Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration

Andrews, Margaret M. PhD, RN, CTN

Author Information

Margaret M. Andrews, PhD, RN, CTN, Chairperson and Professor, Department of Nursing, e-mail:mmandrew@naz.edu, Nazareth College, Rochester, New York.

Abstract

Population demographics are reshaping the healthcare work force with respect to race, ethnicity, gender,

national origin, sexual orientation, age, handicap, disability, and related factors as national sensitivity to various

forms of diversity grows. Given the demographic trends, it is inevitable that nurse administrators will need skill in

transcultural administration as they manage diversity and identify the cultural origins of conflict in the multicultural

workplace. Culture influences the manner in which administrators, staff and patients perceive, identify, define and

solve problems. In this article, the complex and interrelated factors that influence workplace diversity are examined.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 9%, or 207,000, of the 2.24 million registered

nurses (RNs) in the United States come from racial or ethnic minority backgrounds.1 Although fewer than 4% of

licensed nurses in the United States are foreign-educated, this represents 73,423 nurses. These figures do not reflect

the variation that exists within panethnic population categories, nor differences related to religion, age, gender,

sexual orientation, size, disability, handicap, or other forms of diversity.

A significant number of the Healthy People 20002 goals involve specific objectives for improving the health

status of racial and ethnic minorities, particularly those with low incomes. As the year 2000 approaches, culturally

diverse cohorts of children, women of childbearing age, and the elderly are expected to grow, exacerbating the need

for culturally and gender-sensitive providers of healthcare. Since 1972, there has been an explosion in the numbers of

people migrating to the United States, both with and without legal documentation. Overall, 8%, or 19.8 million

people, in the United States are foreign-born residents from other North American nations (41%), Asia (25%), Europe

(29%), South America (5%), Africa (2%), the former Soviet Union (2%), and Oceania (1%).3

By the year 2000, immigrants, women, and minorities will account for 85% of the net growth in the labor force.

Women will account for more than 46% of the total work force, and 61% of all American women will be employed.

African Americans will comprise 12% of the labor force, Hispanics 10%, Asians and Pacific Islanders 3%, and Native

Americans 1%. More than 25% of the work force will be comprised of people from Third World countries. People 35 to

54 years of age will make up 51% of the work force, whereas those aged 16 to 24 years will decline to approximately

8%.1-7

Transcultural nursing administration refers to the "process of assessing, planning, and making decisions and

policies that will facilitate the provision of educational and clinical services that take into account the cultural caring

values, beliefs, symbols, references, and lifeways of people of diverse and similar cultures for beneficial or satisfying

outcomes."4(p30) Transcultural perspectives in nursing administration are essential for survival, growth, satisfaction,

and achievement of goals in the multicultural workplace. With increasing frequency, nurse administrators are

realizing the importance of transculturally based administrative practices that positively influence cost benefits and

quality outcomes. With the increasing diversity among members of the healthcare work force, nurses are challenged

to develop and practice a new kind of administration that incorporates transcultural concepts.

Cultural Perspectives on the Meaning of Work

In contemporary society, the concept of work must be considered in its historical and cultural context. Cultural

views about those who care for the sick are complex and nursing may be perceived as a divine calling for those with

supernatural powers (some African and Hispanic groups), a religious vocation (some ethnic Catholic groups, such as

the Irish), or an undignified occupation for lower class workers (some Arab groups, such as Kuwaitis and Saudi

Arabians).

Ovid: Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.silk.library.umass.edu/sp-3.13.0b/ovidwe...

1 of 9 9/20/14 2:27 PM

There are two prevailing paradigms concerning the orientation to work, individualism or collectivism. With

individualism, importance is placed on individual inputs, rights, and rewards. Individualists emphasize values such as

autonomy, competitiveness, achievement, and self-sufficiency. Most English-speaking and European countries have

individualist cultures.

Collectivism entails the need to maintain group harmony above the partisan interests of subgroups and

individuals. In collectivist cultures, values such as interpersonal harmony and group solidarity prevail. Staff whose

ethnic heritage is Asian or South American are likely to be influenced by collectivism. Amish and Mennonite groups

also are considered collectivist cultures. One of the most notable distinctions between people from individualist and

collectivist cultures is the meaning of work.

Individualists work to earn a living. People are expected to work and need not enjoy it. Leisure or recreational

activities frequently are pursued to alleviate the monotony of work, and they tend to dichotomize work and leisure.

Individualist concepts of work reflect an orientation toward achievement and the future. They want to do better,

accomplish more, and take responsibility for their actions, which results in the development of personality traits such

as assertiveness and competitiveness.

In many collectivist cultures, conversely, people expect to find satisfaction in job-related relationships, have less

clearly delineated boundaries between work and leisure, and focus on the present. Qualities such as commitment to

relationships, gentleness, cooperativeness, and indirectness are valued. Although some individuals exhibit a

combination of the two, most staff will display either an individualistic or collectivistic orientation in the workplace.

Nurse administrators need to recognize the fundamental value system embraced by their staff to understand why

they behave as they do at work.

Corporate Cultures and Organizational Climate

Healthcare organizations are minisocieties that have their own distinctive patterns of culture and subculture.

One organization may have a high degree of cohesiveness with staff working together, like members of a single family

toward achievement of common goals. Another may be highly fragmented, divided into groups that have different

aspirations as to what their organization should be. Corporate culture refers to a process of reality construction that

allows staff to see and understand particular events, actions, objects, communications, or situations in distinctive

ways. Shared values, beliefs, meaning, and understanding are components of the corporate culture. One of the

easiest ways to appreciate the nature of corporate culture is to observe the day-to-day functioning of the

organization. Note the patterns of interaction among individuals, the language that is used, the images and themes

explored in conversation, and the various rituals of daily routine. Although the corporate or organizational culture

consists of what its members share, often unconsciously, concerning beliefs, values, assumptions, rituals, the

organizational climate usually measures perceptions or feelings about the organization or work environment.5

Nurse administrators should be committed to multiculturalism at all levels of the organization and periodically

should review mission statements and policies as they relate to diversity. They should actively encourage the

recruitment of diverse staff and administrators and be alert for overt and covert evidence of prejudice and

discrimination in their organizations. A policy of zero tolerance should be established concerning negative behaviors

that are based on race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, national origin, class, or handicap/disability.

Ethnic violence should be grounds for immediate dismissal and reported to the proper authorities.

Cultural Values

Because they form the core of a culture, values frequently lie at the root of cross-cultural differences in the

multicultural work place. Time orientation, family obligations, communication patterns (including etiquette,

space/distance, touch), interpersonal relationships (including long-standing historic rivalries), gender/sexual

orientation, education, moral/religious beliefs, hygiene, clothing, and beliefs about the meaning of work are shaped

by cultural values.6-9

What is the importance of learning about the values of people from diverse cultural groups? Values exert a

powerful influence on how each person behaves, reacts, and feels. In the multicultural workplace, values affect

people's lives in four major ways. Values underlie perceived needs, what is defined as a problem, how conflict is

resolved, and expectations of behavior. When cultural values of individual staff members conflict with the

organizational values or those held by coworkers, challenges, misunderstandings, and difficulties in the workplace

become inevitable. Nurse administrators must examine the underlying values orientation to identify the root cause of

the conflict and to foster cross-cultural understanding among staff and patients from diverse backgrounds.

Ovid: Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.silk.library.umass.edu/sp-3.13.0b/ovidwe...

2 of 9 9/20/14 2:27 PM

Cultural Perspectives on Conflict

The term conflict is derived from Latin roots (confligere, to strike against) and refers to actions that range from

intellectual disagreement to physical violence. Frequently, the action that precipitates the conflict is based on

different cultural perceptions of the situation. As indicated in Figure 1, the nursing administrator must consider

influences on organizations, such as political, economic, legal, technological, and religious factors (especially for

organizations owned and operated by religious groups) and influences on individuals, such as educational

background, socioeconomic status, family obligations, political orientation, cultural factors, moral and religious

beliefs, and personal traits (e.g., age, gender, size, state of physical and emotional health, and others). Both the

organization and the individuals within it are influenced by the corporate culture, organizational climate, and

cultural meaning of work. The organization's cultural meaning of work usually can be identified through its mission

statement, personnel policies, job descriptions, and related documents.

Figure 1. Origins of conflict in the multicultural healthcare setting. * = factors apply especially to organizations

owned and operated by religious groups.

Nurse administrators from individualist cultures are likely to view conflict as a healthy, natural, and inevitable

component of all relationships. People from many collectivist cultures, however, have learned to internalize conflict

and value harmonious relationships above winning arguments. To many people of Native American and Asian descent,

conflict is considered unhealthy, undesirable, and nonconstructive. In the Arab world, mediation is critical in

resolving disputes, and confrontation seldom works. Mediation allows for saving face and is rooted in the realization

that all conflicts do not have simple solutions. The assertive, confrontational, direct style of communicating is

characteristic of people from individualistic cultures, whereas the cooperative, conciliatory style is a more

collectivist or Eastern mode of managing conflict. When attempting to influence others during a disagreement, for

example, nurses from Chinese American, Japanese American, or other collectivist cultures may employ covert

conflict prevention strategies to minimize interpersonal conflicts. Nurses from individualistic cultures are more likely

to rely on the overt confrontation of ideas and argumentation by reason. When participants in a conflict are from the

same culture, they are more likely to perceive the situation in the same way and organize their perceptions in similar

ways.

Some of the more frequently encountered cultural origins of conflict in the multicultural workplace may be

traced to differences in one or more of the following: cross-cultural communication (including touch, space,

distance, and etiquette), interpersonal relationships involving authority, peers and patients, time orientation,

gender/sexual orientation, family obligations, moral and religious beliefs, personal hygiene, clothing and accessories,

and longstanding historic rivalries between groups.

Cross-Cultural Communication

Underlying the majority of conflict in the multicultural healthcare setting are issues related to effective verbal

or nonverbal communication. Even when dealing with staff from the same cultural background, it requires

administrative skill to decide whether to speak with someone face to face, send an electronic or paper

memorandum, contact by telephone, or opt not to communicate about a particular matter at all. The nurse manager

must exercise considerable judgment when making decisions about methods for effectively communicating with staff

members and patients from diverse cultural backgrounds, including a sense of timing, tone and pitch of voice, choice

of location for face-to-face interactions, and related considerations. Communication difficulties caused by

language/accent issues become compounded on the telephone. It sometimes is necessary to counsel recent

Ovid: Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.silk.library.umass.edu/sp-3.13.0b/ovidwe...

3 of 9 9/20/14 2:27 PM

immigrants from non-English-speaking countries to refrain from giving or receiving medical orders by telephone until

their English language skills have developed. Approximately 32 million people (14% of the total U.S. population) speak

languages other than English. In rank order, the most frequently spoken languages are Spanish, 54%; French, 6%;

German, 5%; Italian, 4%; and Chinese, 4%. As the 21st century draws near, it is estimated that the United States will

continue to attract approximately two thirds of the world's immigrants, 85% of whom will come from Central and

South America (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1993). Figure 2 identifies strategies for promoting effective cross-cultural

communication in the multicultural workplace.

Figure 2. Strategies to promote effective cross-cultural communication in the multicultural workplace.

Cultural Perspectives on Space, Distance, and Touch

Although there are wide variations in spatial requirements, people of the same culture tend to act similarly.

Because people usually are not consciously aware of their personal space requirements, they frequently have

difficulty understanding a different cultural pattern. For example, sitting closely to another may be perceived as a

sign of warmth and friendliness by some staff members but as a threatening invasion of personal space by another.

Anglo and African American nurse administrators may find themselves backing away from staff members of Hispanic,

East Indian, or Middle Eastern origins, who seemingly invade their personal space.

In general, nurses from Asian cultures are less tactile and show affection in a more reserved manner than Anglo

or African American nurses, who may be perceived as boisterous, loud, ill-mannered, or rude by comparison. In some

cases, staff members from different cultures may send messages through their use of touch that are not intended.

Special attention is warranted for male-female relationships in the multicultural workplace. In general, it is best to

refrain from touching staff members of either gender unless warranted for accomplishment of a job-related task,

such as the provision of safe patient care. Nurses who tend to be more tactile should consciously refrain from placing

their hand on another's arm or shoulder, as frequently happens during ordinary conversation.

Cultural Perspectives on Etiquette and Interpersonal Relationships

Ovid: Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.silk.library.umass.edu/sp-3.13.0b/ovidwe...

4 of 9 9/20/14 2:27 PM

Etiquette refers to the conventional code of good manners that governs behavior. Etiquette is included in this

discussion of the origins of conflict because it concerns culturally appropriate ways for people to show respect in

their relationships with one another and promotes effective cross-cultural communication. For example, some people

from Hispanic, Middle Eastern, and African cultures expect the nurse manager to engage in social conversation and

establish personal/social rapport before giving assignments or orders for the day's work. In developing interpersonal

relationships, there is a high value placed on getting to know about a person's family, personal concerns, and

interests before discussing job-related business. The nurse administrator's reluctance to engage in self-disclosure

about personal matters or inquire about the staff member's family may leave the impression that he or she is

uncaring and disinterested. These behaviors by the administrator are not conducive to building productive,

harmonious relationships and may be misunderstood by staff members from diverse backgrounds. Similarly, some

cultures value formal greetings at the start of the day or whenever the first encounter of the day occurs, a practice

found even among close family members. Although most people appreciate a courteous greeting, staff members from

some cultures may view the nurse administrator's failure to begin conversations with formal greetings as a

disrespectful breech of etiquette that conveys the message that they are not valued or appreciated.

Cultural Perspectives on Time Orientation

In some instances, cultural differences in time orientation create difficulty in the workplace. This may manifest

itself when staff members are tardy, take excessive time for breaks, or fail to complete assignments within the

expected time frame. These differences may be interrelated with the cultural meaning of work, religious practices,

and cross-cultural communication issues. Administrators must be explicit in the job-related expectations about

punctuality, schedule for breaks, and time allotted for assignments.

If a staff member develops a pattern of tardiness, the reason(s) should be explored. Although there needs to be

a uniform standard applied to all staff members concerning punctuality, it may be useful to listen to the staff

member's explanation and ask what he or she thinks might rectify the problem. Reasons for punctuality problems may

range from child care to car repair needs. Solutions may include the mobilization of cultural resources, such as using

extended family members to look after dependents or networking with coworkers who might be able to recommend a

reliable auto mechanic. Listen attentively without rendering judgment or dictating solutions to which the person has

not agreed.

It sometimes is useful to divide an assignment into subtasks with specific time lines for each activity. If the staff

member has difficulty completing the assignment within the allotted time, follow-up with a discussion of the reasons

why there were problems. This follow-up should be conducted in a positive, proactive manner and viewed as an

opportunity to promote cross-cultural communication, not as a punitive or disciplinary measure.

Cultural Perspectives on Gender and Sexual Orientation

The complex interrelationship between gender and culture frequently challenges nurse managers. Nurses of both

genders may face the biases and preconceptions of physicians, nurse colleagues, other healthcare providers, and

patients. The issue is further complicated by cultural beliefs about relationships with authority figures and cross-

national perspectives on the status or prestige of various healthcare disciplines.

In the multicultural healthcare workplace, both men and women face the gender biases that exist in society.

These issues frequently emerge in verbal and nonverbal communication and in interpersonal relationships. Our

language also belies covert gender biases and preconceptions. For example, the expression male nurse sometimes is

used but seldom does one hear about the female nurse because it is considered redundant and unnecessary.

Workplace issues concerning gay, lesbian, and bisexual staff also are important in the multicultural setting.

Cultural Perspectives on Family Obligations

Although family is important in all cultures, the constellation (nuclear, single-parent, extended, same-sex, etc.),

emotional closeness, social and economic commitments among members, and other factors vary cross-culturally. Both

staff nurses and those in administrative positions frequently report difficulty with requests from nurses of diverse

cultural background that pertain to family obligations.

Some nurses from diverse cultures have been labeled as uncommitted to their work or disinterested in their

nursing careers because their family is a higher priority than their profession. From an administrative perspective,

the most useful approach is to focus on the problematic behavior. For example, if excessive absenteeism is the

undesirable behavior, the nurse administrator should arrange for a face-to-face meeting in which the problematic

behavior is discussed. If used judiciously, peer pressure by coworkers can be helpful in changing the undesirable

behavior as fellow workers communicate to the individual why his or her behavior is troublesome. It generally is

useful to identify the reason(s) for the excessive absenteeism and to explore culturally appropriate strategies for

resolving the problem, such as utilization of the natural social support that is culturally expected of extended family

members.

Ovid: Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.silk.library.umass.edu/sp-3.13.0b/ovidwe...

5 of 9 9/20/14 2:27 PM

Ideas about the importance of anticipating and controlling the future vary significantly from culture to culture.

Whereas some staff members place a high priority on planning for retirement, accumulating sick days, and purchasing

insurance, other staff, particularly recent immigrants with family obligations in their homeland, might be more

concerned with current obligations and living in the present. Similarly, some workers in high-risk positions participate

actively in preventive immunization programs, such as those aimed at hepatitis and influenza, whereas others

demonstrate a fatalistic view of future illnesses.

Cultural Perspectives on Moral and Religious Beliefs

In some circumstances, moral and religious beliefs may underlie conflicts in the multicultural workplace.

Consider the following dilemmas. A staff nurse who believes that it is morally wrong to drink alcohol refuses to carry

out a physician's order for the therapeutic administration of alcohol as a sedative/hypnotic or to administer

medicines with an alcohol base. A nurse who believes that humankind should not unleash the power of nuclear energy

refuses to care for irradiated cancer patients. A Roman Catholic nurse working in the operating room refuses to scrub

for abortions, tubal ligations, vasectomies, and similar procedures because of religious prohibitions. A nurse who is a

member of Jehovah's Witnesses refuses to hang blood or counsel patients concerning blood or blood products. A

Seventh-Day Adventist nurse who cites Biblical reasons for following a vegetarian diet is unwilling to do patient

education involving diets that contain meat. Muslim and Jewish staff members express concern that the hospital

cafeteria fails to serve foods that are halal or kosher.

In the clinical world, the options available to accommodate the diverse moral and religious beliefs of staff

members frequently depend on the size of the organization, moral and religious proclivities of coworkers, attitudes

and beliefs of nurse managers, organizational climate, fiscal constraints, and related factors. In some cases, it may

be impossible to provide the services demanded by the organization's mission if all nurses were to refuse to engage in

a particular activity because of moral or religious prohibitions. There may be legal implications for refusing to

provide patients with certain services, such as those related to reproductive health. The challenge facing nurse

administrators is to balance the conflicting moral and religious beliefs of diverse groups with achievement of

organizational goals in a manner that is respectful of the moral and religious beliefs of staff members and patients.

Cultural Perspectives on Personal Hygiene

Among the more sensitive issues faced by nurse administrators is counseling a staff member about offensive body

odor. In some cultures, people are not bothered unduly by body odors and they refrain from masking nature's original

smells. In some cases, the staff member may come from a country in which water is scarce and bathing is restricted.

The staff member may be following religious or cultural practices that prohibit bathing during certain phases of the

menstrual cycle, after delivery of a baby, and at other times. Nurse managers and other supervisors frequently find

the sensitive topic of hygiene difficult to discuss with staff members from diverse cultural backgrounds.

Cultural Perspectives on Clothing and Accessories

Most healthcare organizations have a dress code or policy statement about clothing and accessories worn by staff

members, with some variation for specialty units such as the operating room. These documents should be reviewed

periodically from a cultural perspective. For example, modification of the dress code might be necessary to

accommodate Hindu women dressed in a sari, Sikh men who wear a turban, Amish and Mennonite women who wear

bonnets, Muslim women and Catholic nuns who cover their heads with veils, Arab men who cover their heads with a

khafia, or Jewish men who wear a yarmulka (skull cap). Special consideration may need to be given to some African

Americans and others who wear jewelry and other accessories in their hair, particularly when the hair is braided.

Care should be exercised to establish policies that incorporate both cultural and gender-related sensitivities.

Long-Standing Historic Rivalries

Some historians have referred to the 1900s as the Century of War. On occasion, the multicultural workplace

becomes a battleground on which long-standing historic rivalries and more recent geopolitical differences are

re-enacted in the form of interpersonal conflict between two or more staff members. After ruling out other potential

sources of conflict, it may be worth examining the ethnic heritage and national origins of staff for possible reasons.

For example, the nurse manager may observe a pattern of strained relationships between an Israeli physician and

Palestinian physicians, nurses, laboratory technicians, physical therapists, and other healthcare providers. Similar

observations may be made concerning staff from known rival countries, such as North and South Koreans, Russians

and Armenians, Iranians and Iraqis, Indians and Pakistanis, and so forth. Cues that may signal underlying historic

rivalries include: 1) the expression of high levels of emotional energy when interacting with a person from a rival

group when the topic does not seem to warrant it; 2) sudden, uncharacteristic behavior changes when in the

presence of a person from the rival group, for example, an ordinarily cordial staff member unexpectedly becomes

acrimonious for no apparent reason; 3) the repeated expression of strong opinions about historical, political, and

current events involving rival nations or factions; and 4) inappropriate attempts to persuade others to adopt partisan

views about the rivalry.

Ovid: Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.silk.library.umass.edu/sp-3.13.0b/ovidwe...

6 of 9 9/20/14 2:27 PM

International Perspectives on Conflict

Discrepancies in role expectations tend to create intrapersonal and interpersonal conflict. For example, nurses in

Taiwan, the Philippines, and many African nations may expect the families of patients to bathe and feed their loved

ones. Because of the shortage of qualified healthcare providers in many less developed countries, there usually are

fewer interdisciplinary differences about the nature and scope of practice for various healthcare disciplines. Nurses

frequently have considerably expanded roles, and their scope of practice is correspondingly broader. For example,

the Nigerian Board of Nursing and Midwifery allows nurses to diagnose and treat common illnesses, such as malaria,

typhoid, cholera, tetanus, and many other communicable diseases.

In many nations, nurses and nurse midwives primarily are responsible for obstetric care. To graduate from a

nursing program in the Philippines, nursing students must deliver a minimum of 25 babies unassisted and assist at

major and minor surgeries. In Haiti, nurses routinely start intravenous lines, perform episiotomies, and repair

lacerations. There also are various categories of licensed and unlicensed healthcare providers who contribute to the

overall health and well-being of people in countries around the world.

Nurse administrators may be called on to resolve conflict related to role expectations that involve graduates of

foreign nursing programs, physicians, patients, visiting family members, and others. Sometimes altercations may

involve security guards, police, and other authority figures, especially among nurses who have experienced

government oppression in their country of origin. It should be noted that physicians, auxiliary staff members, and

others in the healthcare setting who have been educated abroad also may bring different role expectations to the

multicultural workplace.

Working Together in the Multicultural Workplace

Throughout this article, considerable attention has been given to assessing the cultural needs of individual staff

members from diverse groups and communicating effectively with them. In the multicultural healthcare setting,

nursing administrators frequently are challenged to balance the needs of individual staff members from diverse

cultures with the overall good of the healthcare team. Nursing administrators are expected to create an

organizational climate that values and recognizes diversity, yet supports team work and accountability in a manner

that is fair and equitable for all staff.

Nursing administrators must review carefully the criteria for evaluation for cultural bias and ensure that they are

worded in a manner that enables staff from diverse cultures to achieve standards. These standards must be

communicated to all staff members, at the time of initial employment and at periodic intervals. Ensure that staff

members understand what is meant by working together or building teams or other expressions that reflect

organizational values.

In most instances, staff members expect nursing administrators to establish and enforce policies that avoid giving

preferential treatment to any individual or group. At the same time, they want a work environment that allows

sufficient flexibility to accommodate their individual needs. Although staff members expect the nursing

administrators to be fair in their expectations concerning work load and job-related responsibilities, they also want

their performance evaluations to reflect accurately the effort and hard work that they have put forth. If staff

members perceive that a peer from a diverse cultural background is doing less work or being evaluated less

rigorously, they may lose confidence in their manager, engage in behaviors that undermine the group's effectiveness,

or show evidence of morale problems. While being responsive to individual staff needs, the nursing administrator

must focus on the overall organizational mission, goals, and objectives and encourage staff members to work

collaboratively.

Conclusion

Given the demographic trends, nurse administrators in the next decade will continue to search for cultural

origins of conflict in the multicultural workplace. As a microcosm of society at large, healthcare organizations,

institutions, and agencies consist of staff members and patients from increasingly diverse backgrounds.

Culture influences the manner in which people communicate with one another and how they perceive, identify,

define and solve problems in the workplace. Among the complex and interrelated factors that must be considered

when addressing workplace diversity are cultural perspectives on values, the meaning of work, interpersonal

relationships, cross-cultural communication patterns (including touch, space/distance, and etiquette), interpersonal

relationships involving authority figures, peers and patients, gender and sexual orientation, moral and religious

beliefs, hygiene, clothing and the use of accessories, and long-standing historic rivalries between groups.

Ovid: Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.silk.library.umass.edu/sp-3.13.0b/ovidwe...

7 of 9 9/20/14 2:27 PM

Select All

Export Selected to PowerPoint

When cross-cultural miscommunication and conflict involves nurses, physicians, or others who have been

educated abroad, nursing administrators must explore cross-national differences in role expectations, scope of

practice, status or prestige associated with various health-related disciplines, exposure to oppressive governments,

attitudes toward authority, and global politics. Characteristics of the staff member, such as individual preferences,

biases for and against certain groups, prejudice, educational background, and prior experiences living and working in

culturally diverse settings, also must be considered.

Understanding cultural differences in the workplace and developing skill in conflict resolution will continue to be

needed in transcultural nursing administration as the next millennium approaches. The successful transcultural nurse

administrator will behave respectfully toward others from diverse backgrounds and will implement policies that

promote cultural understanding, knowledge, and skill in the workplace. They also will be sensitive to the overall

needs of the entire healthcare team and work toward using the differences in achieving organizational goals.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Bureau of Health Professions. Fact Sheet: Selected Facts About

Minority Registered Nurses. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1993. [Context Link]

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease

Prevention Objectives. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 1992. [Context Link]

3. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Place of birth of foreign-born persons.In: 1990 Census of Population, Social and

Economic Characteristics, United States. Series 1990. CP-2-1. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office;

1993:12. [Context Link]

4. Leininger MM. Founder's focus: transcultural nursing administration: an imperative worldwide. J Transcult Nurs.

1996;8(1):28-33. [Context Link]

5. Flarey DL. The social climate of work environments. J Nurs Adm. 1993;23(6):9-15. Buy Now [Context Link]

6. Andrews MM, Boyle JS. Transcultural Concepts in Nursing Care. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Context

Link]

7. Henderson G. Cultural Diversity in the Workplace. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1994. [Context Link]

8. Morgan G. Images of Organization. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1997. [Context Link]

9. Schwartz RH, Sullivan DB. Managing diversity in hospitals. Health Care Manage Rev. 1993;18(2):51-56. Buy Now

[Context Link]

IMAGE GALLERY

Ovid: Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.silk.library.umass.edu/sp-3.13.0b/ovidwe...

8 of 9 9/20/14 2:27 PM

Figure 1

Figure 2

Back to Top

Copyright (c) 2000-2014 Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Terms of Use Support & Training About Us Contact Us

Version: OvidSP_UI03.13.00.138, SourceID 62446

Ovid: Transcultural Perspectives in Nursing Administration. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.silk.library.umass.edu/sp-3.13.0b/ovidwe...

9 of 9 9/20/14 2:27 PM

You might also like

- Cultural Diversity in The Health Care Workforce: By. Ns. Wulan PurnamaDocument21 pagesCultural Diversity in The Health Care Workforce: By. Ns. Wulan Purnamaeka peranduwinataNo ratings yet

- Culturally Competent NursingDocument40 pagesCulturally Competent NursingmuhiqbalyunusNo ratings yet

- Transcultural Nursing CareDocument44 pagesTranscultural Nursing Careminayoki100% (1)

- Trans Cultural NursingDocument29 pagesTrans Cultural NursingJude Bello-Alvear100% (1)

- Cultural-Competence-In-Health-History-Physical-Examination-and-Influence-of-Cultural-and-Health-Belief-Systems-on-Health-PracticesDocument56 pagesCultural-Competence-In-Health-History-Physical-Examination-and-Influence-of-Cultural-and-Health-Belief-Systems-on-Health-PracticesMary Jane TiangsonNo ratings yet

- A Report On Cultural DiversityDocument9 pagesA Report On Cultural Diversityguest096350% (2)

- Research Paper On Cultural DiversityDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Cultural Diversityfyr60xv7100% (1)

- CultureDocument21 pagesCultureakhilNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity in Nursing PracticeDocument3 pagesCultural Diversity in Nursing PracticeEli Xma100% (2)

- Chapter 9 Nursing Celebrates Cultural DiversityDocument12 pagesChapter 9 Nursing Celebrates Cultural DiversityDon DxNo ratings yet

- Transcultural NursingDocument76 pagesTranscultural NursingSHAYNE MERYLL CHANNo ratings yet

- Trans CulturalDocument74 pagesTrans CulturalAirah Ramos PacquingNo ratings yet

- Module 4: Culturally Competent Health Care ObjectivesDocument9 pagesModule 4: Culturally Competent Health Care ObjectivesJhucyl Mae GalvezNo ratings yet

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model For Cultural Competence. Journal of Transcultural NursingDocument10 pagesPurnell L. The Purnell Model For Cultural Competence. Journal of Transcultural NursingCengizhan ErNo ratings yet

- The Purnell Model For Cultural CompetenceDocument11 pagesThe Purnell Model For Cultural CompetenceJoebert BangsoyNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity and NursingDocument21 pagesCultural Diversity and Nursingfatha83% (6)

- Trans CulturalDocument97 pagesTrans CulturalkewlangotNo ratings yet

- Culturally Responsive Social Work MethodsDocument20 pagesCulturally Responsive Social Work MethodsjHen LunasNo ratings yet

- Transcu AssignmentDocument9 pagesTranscu AssignmentCharles Gerard B. BeluanNo ratings yet

- 1.seminar Transcultural Nursing-1Document29 pages1.seminar Transcultural Nursing-1Reshma rsr100% (3)

- Cultural Competence Class 1Document5 pagesCultural Competence Class 1theresajamendolaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Foundations of Transcultural NursingDocument12 pagesTheoretical Foundations of Transcultural NursingCeri LeeNo ratings yet

- For Language - EditedDocument52 pagesFor Language - EditedALAYSHA ALINo ratings yet

- For LanguageDocument52 pagesFor LanguageALAYSHA ALINo ratings yet

- Cultural CompetenceDocument19 pagesCultural Competencekmurphy100% (6)

- HWC 535 - Week 2 - Calzada & Balcezar (2014) - Enhancing Cultural Competence in Social Service AgenciesDocument8 pagesHWC 535 - Week 2 - Calzada & Balcezar (2014) - Enhancing Cultural Competence in Social Service AgenciesStephanie ANo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics Cultural DiversityDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Topics Cultural Diversityvstxevplg100% (1)

- Chapter 1 Introduction To Cultural DiversityDocument12 pagesChapter 1 Introduction To Cultural Diversitynur atikah67% (3)

- Term Paper On Cultural DiversityDocument6 pagesTerm Paper On Cultural Diversityafmzhpeloejtzj100% (1)

- Cultural Awareness, Safety and CompetenceDocument27 pagesCultural Awareness, Safety and CompetenceShavyata Thapa100% (1)

- Cultural Concepts in Nursing CareDocument27 pagesCultural Concepts in Nursing Caremuhammad adilNo ratings yet

- Chcdiv001 - Work With Diverse People: Assessment 1 Answer QuestionsDocument10 pagesChcdiv001 - Work With Diverse People: Assessment 1 Answer QuestionsNidhi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Purnells ModelDocument35 pagesPurnells ModelRheaNo ratings yet

- Correlates of Cultural Self-Awareness and Turnover Intention of Staff Nurses in Multicultural Diverse EnvironmentDocument55 pagesCorrelates of Cultural Self-Awareness and Turnover Intention of Staff Nurses in Multicultural Diverse EnvironmentRaima CABARONo ratings yet

- Transcultural NursingDocument14 pagesTranscultural NursingAnonymous Ma6Fdf5BLB100% (1)

- Seminar Transcultural NursingDocument13 pagesSeminar Transcultural Nursingjyoti singhNo ratings yet

- Transcultrural Nursing PDFDocument6 pagesTranscultrural Nursing PDFSarithaRajeshNo ratings yet

- Transcultural NursingDocument12 pagesTranscultural NursingSathish RajamaniNo ratings yet

- Transcultural Nursing TheoryDocument44 pagesTranscultural Nursing TheoryShweta KateNo ratings yet

- Competency Based Organizational Culture PDFDocument9 pagesCompetency Based Organizational Culture PDFMonika ShindeyNo ratings yet

- Transcultural NursingDocument14 pagesTranscultural NursingJennifer DixonNo ratings yet

- Culturally Competent CareDocument3 pagesCulturally Competent CarePrincess Agarwal100% (1)

- Fundamentals of Nursing: Culturallly Responsive Nursing CareDocument8 pagesFundamentals of Nursing: Culturallly Responsive Nursing CareNisvick Autriz BasulganNo ratings yet

- SOCS350 FinalexamDocument6 pagesSOCS350 FinalexamShyamjes InnNo ratings yet

- Transcultural NursingDocument32 pagesTranscultural Nursingnovi100% (2)

- Culture and Ethnicity IsmailaDocument29 pagesCulture and Ethnicity IsmailaIsmaila Sanyang100% (1)

- TRANSCULTURAL NURSING: LEININGER'S THEORY AND CULTURE CARE MODELDocument10 pagesTRANSCULTURAL NURSING: LEININGER'S THEORY AND CULTURE CARE MODELCiedelle Honey Lou DimaligNo ratings yet

- Culturally Competent For NursesDocument9 pagesCulturally Competent For Nursesleli khairaniNo ratings yet

- At LTC N Theories Models 1Document35 pagesAt LTC N Theories Models 1Darin BransonNo ratings yet

- Cultural Awareness and Competence ReflectionDocument7 pagesCultural Awareness and Competence Reflectionapi-301725327No ratings yet

- Chapter 02 Social and Cultural Context of IHRMDocument5 pagesChapter 02 Social and Cultural Context of IHRMJyothi Mallya50% (2)

- Multicultural Perspective and HealthcareDocument70 pagesMulticultural Perspective and HealthcareFarach Aulia PutriNo ratings yet

- How Cultural Identity Influences Health For Individuals and CommunitiesDocument6 pagesHow Cultural Identity Influences Health For Individuals and Communitiesclive muchokiNo ratings yet

- SUP 1033-Group-4-Assignment-2Document6 pagesSUP 1033-Group-4-Assignment-2Robin BNo ratings yet

- TCN FilesDocument31 pagesTCN FilesMarianee RojeroNo ratings yet

- Transcultural Nursing: Presented by Rohini Rai M SC Nursing, Part - I College of Nursing, N.B.M.C.HDocument37 pagesTranscultural Nursing: Presented by Rohini Rai M SC Nursing, Part - I College of Nursing, N.B.M.C.HRohini Rai100% (1)

- Clinical Social Work with Latinos in New York-USA: Emotional Problems during the Pandemic of Covid-19From EverandClinical Social Work with Latinos in New York-USA: Emotional Problems during the Pandemic of Covid-19No ratings yet

- A Cross-Cultural Investigation of Person-Centred Therapy in Pakistan and Great BritainFrom EverandA Cross-Cultural Investigation of Person-Centred Therapy in Pakistan and Great BritainNo ratings yet

- A Biographical Reflection of Being a Latin American Clinical Social Worker in the United StatesFrom EverandA Biographical Reflection of Being a Latin American Clinical Social Worker in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- King Rush MoreDocument1 pageKing Rush MoreawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Oop Say You Know MeDocument1 pageOop Say You Know MeawuahbohNo ratings yet

- The BSN Job Search: Interview Preparation: Telling Your StoryDocument25 pagesThe BSN Job Search: Interview Preparation: Telling Your StoryawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Probability of A or B and A and B-1Document2 pagesProbability of A or B and A and B-1awuahbohNo ratings yet

- Massachusetts Department of Public HealthDocument24 pagesMassachusetts Department of Public HealthawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Article For JournalDocument6 pagesArticle For JournalawuahbohNo ratings yet

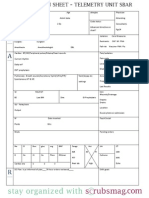

- Nurse Brain Sheet Telemetry Unit SBARDocument1 pageNurse Brain Sheet Telemetry Unit SBARvsosa624No ratings yet

- Middle Age Adult Health History Assignment Guidelines N315 Fall 2013Document23 pagesMiddle Age Adult Health History Assignment Guidelines N315 Fall 2013awuahbohNo ratings yet

- HandOff SampleToolsDocument9 pagesHandOff SampleToolsOllie EvansNo ratings yet

- NCLEX Random FactsDocument34 pagesNCLEX Random FactsLegnaMary100% (8)

- Pharm NclexDocument9 pagesPharm NclexawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Article For CET CHFDocument5 pagesArticle For CET CHFawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking StrategiesDocument3 pagesCritical Thinking StrategiesawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Random FactsDocument338 pagesRandom Factscyram81100% (1)

- PolypharmacyDocument24 pagesPolypharmacySurina Zaman HuriNo ratings yet

- Debate 3 Youth Incarceration in Adult PrisonsDocument6 pagesDebate 3 Youth Incarceration in Adult PrisonsawuahbohNo ratings yet

- EBP Article 1Document11 pagesEBP Article 1awuahbohNo ratings yet

- EBP Article 3Document6 pagesEBP Article 3awuahbohNo ratings yet

- Does Prospective Payment Increase Hospital (In) Efficiency? Evidence From The Swiss Hospital SectorDocument24 pagesDoes Prospective Payment Increase Hospital (In) Efficiency? Evidence From The Swiss Hospital SectorawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Tips On Answering NclexDocument4 pagesTips On Answering NclexawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic CommunicationDocument1 pageTherapeutic CommunicationawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Drugs NclexDocument30 pagesDrugs Nclexawuahboh100% (1)

- ENT Throat and EsophagusDocument41 pagesENT Throat and EsophagusMUHAMMAD HASAN NAGRANo ratings yet

- Article For CET CHFDocument5 pagesArticle For CET CHFawuahbohNo ratings yet

- STDA VaricealDocument8 pagesSTDA VaricealDeisy de JesusNo ratings yet

- Article For Journal 4-18-14Document8 pagesArticle For Journal 4-18-14awuahbohNo ratings yet

- Patient Report FormDocument1 pagePatient Report FormawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Article For JournalDocument6 pagesArticle For JournalawuahbohNo ratings yet

- Parkland formula and rule of 9Document8 pagesParkland formula and rule of 9awuahbohNo ratings yet

- Article For Jouranal 2 (498P)Document5 pagesArticle For Jouranal 2 (498P)awuahbohNo ratings yet

- Language Across The CurriculumDocument11 pagesLanguage Across The CurriculumAchu AniNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural Management-4,5,6Document26 pagesCross Cultural Management-4,5,6Mehboob NazimNo ratings yet

- Word-IELTS Band 9 Writing Task 2 Sample Answers - BooksknotDocument192 pagesWord-IELTS Band 9 Writing Task 2 Sample Answers - BooksknotRahim AhmedNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Teacher Education: Eduardo Cavieres-FernandezDocument10 pagesTeaching and Teacher Education: Eduardo Cavieres-FernandezGonxoNo ratings yet

- Development of Teacher and Student ThematicDocument3 pagesDevelopment of Teacher and Student Thematicfadlanramadhan211No ratings yet

- Stuart Hall 2Document11 pagesStuart Hall 2Bayangan Eks HumanNo ratings yet

- Interkulturna Komunikacija - Skripta 2017Document90 pagesInterkulturna Komunikacija - Skripta 2017KnizarnicaRosandaNo ratings yet

- Bandana Purkayastha - Negotiating Ethnicity - Second-Generation South Asian Americans Traverse A Transnational World (2005)Document238 pagesBandana Purkayastha - Negotiating Ethnicity - Second-Generation South Asian Americans Traverse A Transnational World (2005)Muhammad AqilNo ratings yet

- Sap2000 TutorialDocument5 pagesSap2000 TutorialSSNo ratings yet

- Filipino Youth - PuyatDocument275 pagesFilipino Youth - Puyatm.saqatNo ratings yet

- Towards An Intercultural Education - PDF p.103 PDFDocument310 pagesTowards An Intercultural Education - PDF p.103 PDFSandrine CostaNo ratings yet

- James CliffordDocument10 pagesJames CliffordCarmen MenaresNo ratings yet

- Assessment I - WHSRMDocument40 pagesAssessment I - WHSRMCindy Huang0% (4)

- Ccve Syllabus Grade Preparatory - 14.10.2018 - 8th DraftDocument64 pagesCcve Syllabus Grade Preparatory - 14.10.2018 - 8th Draftjonathan.martin3789No ratings yet

- Multicultural Teacher Education For The 21st CenturyDocument17 pagesMulticultural Teacher Education For The 21st CenturyArlene AlmaydaNo ratings yet

- Multilingualism and Language in EducationDocument62 pagesMultilingualism and Language in Educationginger_2011No ratings yet

- Shohamy 2001 Testing PDFDocument19 pagesShohamy 2001 Testing PDFAnindita PalNo ratings yet

- Radical MulticulturalismDocument12 pagesRadical Multiculturalismemil bekaNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesLesson Planapi-445798977No ratings yet

- Banks Multicultural MythsDocument8 pagesBanks Multicultural MythsMegkian DoyleNo ratings yet

- Written Report in Multicultural Diversity in The Workplace For Tourism and ProfessionalDocument4 pagesWritten Report in Multicultural Diversity in The Workplace For Tourism and ProfessionalCyrill HorcaNo ratings yet

- Unity in Diversity Under ThreatDocument2 pagesUnity in Diversity Under ThreatMohammed Zubair BhatiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Understanding DiversityDocument36 pagesChapter 1 - Understanding DiversityPaul Leslie Remo100% (1)

- Essay On Unity in DiversityDocument2 pagesEssay On Unity in DiversityabcNo ratings yet

- Globalization & Dislocation in Novels of Kazuo IshiguroDocument413 pagesGlobalization & Dislocation in Novels of Kazuo Ishiguromleaze100% (1)

- Lesson 8 October 18 2021 Purposive CommunicationDocument3 pagesLesson 8 October 18 2021 Purposive CommunicationReabels FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Donald S. LUTZ (2006) - Principles of Constitutional Design PDFDocument279 pagesDonald S. LUTZ (2006) - Principles of Constitutional Design PDFJorge100% (2)

- Indonesia's Cultural Diversity in 40 CharactersDocument14 pagesIndonesia's Cultural Diversity in 40 CharactersMade SulastyawanNo ratings yet

- Diversity ManagementDocument22 pagesDiversity ManagementJayelleNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document26 pagesChapter 3AlanNo ratings yet