Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Management of Protozoal Diarrhoea in HIV Disease

Uploaded by

Sri Nowo MinartiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Management of Protozoal Diarrhoea in HIV Disease

Uploaded by

Sri Nowo MinartiCopyright:

Available Formats

HIV Medicine (2000) 1, 194199

2000 British HIV Association

REVIEWS IN OPPORTUNISTIC INFECTIONS

Management of protozoal diarrhoea in HIV disease

YM Miao and BG Gazzard*

Department of HIV/GUM, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK

Summary

Since the rst reported case of HIV infection in 1981, many HIV-seropositive patients have died

as a result of diarrhoea induced by opportunistic protozoal infections: pathogens that would

normally cause only a transient illness in immunocompetent individuals. The introduction of

highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1996 has been associated with a signicant

decline in incidence and mortality arising from infections such as cryptosporidia and

microsporidia. Previously, there were no chemotherapeutic agents known to be effective in

eradicating these parasites, but since the availability of HAART, the memory of the emaciated

terminally ill patient with advanced AIDS suffering from refractory diarrhoea will hopefully be a

thing of the past. Signicant advances in the knowledge of the pathogenesis of HIV disease,

earlier detection and thus treatment of the virus, and availability of improved diagnostic

techniques and HAART have transformed the way HIV-associated diarrhoea is managed. In this

review, we look specically at the management of protozoa-induced diarrhoea.

Received: 12 April 2000, accepted 24 June 2000

Introduction

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea has been a common problem in patients with

advanced HIV. Up to two-thirds of patients have suffered

with this symptom at some time during the course of their

illness [1]. Symptoms arise from a wide range of pathogens

[2]. Protozoal infections such as cryptosporidia (Cryptosporidium parvum) and microsporidia (Enterocytozoon

bieneusi and Encepha-litozoon intestinalis) were among

the most common causative organisms and contributed to

the signicant morbidity and mortality seen in advanced

stages of HIV illness [3].

Since the introduction of combination antiretroviral

therapy in 1996 there has been a signicant reduction

in the number of HIV-seropositive patients with

refractory diarrhoea. The incidence of cryptosporidial

and microsporidial infection is declining in conjunction

with the general reduction in morbidity and mortality

witnessed following successful viral suppression with

highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [4].

This article reviews the current management of patients

with protozoal-induced diarrhoea in HIV-seropositive

patients.

Diarrhoea is a very common complaint; however, perception of what is true `diarrhoea' varies widely among

patients [5]. Complaints may vary, from the passage of

abnormal stool consistency to urgency of defecation or to

an increase in frequency of motion.

Mostgastroenterologists woulddene chronicdiarrhoeaas

an increase in frequency of defecation (greater than three

motions per day) and passing more than 200 g/day of stool

weight for a minimum of 1 month as being abnormal [5].

Aetiology

The causes of diarrhoea in the HIV-seropositive population

have changed in recent years. In the past, intestinal

spore-forming protozoa such as cryptosporidia (C. parvum)

and microsporidia (E. bieneusi and E. intestinalis) were

among the most common infective agents [6]. Other

protozoal organisms commonly affecting HIV-seropositive individuals include giardia (Giardia lamblia),

amoeba (Entamoeba histolytica) and, less commonly,

isospora (Isospora belli) and cyclospora (Cyclospora

cayetanensis).

Since the Department of Health issued guidelines in 1994

[7], advising immunocompromised patients to boil all

Correspondence: Professor B.G. Gazzard, Department of HIV Medicine, St

Stephen's Centre, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, 369 Fulham Road,

London SW10 9NH, UK.

194

Management of protozoal diarrhoea in HIV disease 195

drinking water and thus to minimize exposure to the

cryptosporidia found in the water supplies, the incidence of

cryptosporidiosis has declined. This trend has continued

with the introduction of HAART, with a similar trend seen

in those with microsporidial infections [8].

Currently, both conditions are rarely seen in the wellmanaged HIV patient. Previous studies indicated that

long-standing cryptosporidiosis or microsporidiosis was

unusual in patients with a CD4 count above 200 cells/mL

[9,10]. Infection with cryptosporidia tended to be selflimiting with spontaneous resolution within 23 weeks,

and was extremely unusual with microsporidia.

Currently, HIV-seropositive patients are routinely offered

follow-up and tend to be treated with HAART before their

CD4 count falls below 200 cells/mL. Protozoal diarrhoea,

however, must still be remembered in individuals presenting with diarrhoea as their initial AIDS-presenting

diagnosis.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of diarrhoea is incompletely understood.

In HIV patients, the presence of malabsorption features

associated with small bowel villous atrophy and impairment of gut permeability are often found [11]. These

ndings in symptomatic patients with no causative

organism detected were grouped previously into those

with `HIV-induced enteropathy'. However, similar but

milder features can also be seen in asymptomatic HIV

patients [12]. Previous studies have shown disproportionate

reductions in the numbers of CD4 T-cell lymphocytes in the

lamina propria compared to circulating levels of CD4 in the

plasma [13,14]. The number and functional capacity of CD4

cells may be important in controlling villous height [15].

Opportunistic enteroparasites such as cryptosporidia and

microsporidia can produce profound villous atrophy, and

are known to be associated with very low levels of CD4

lymphocytes in the lamina propria [16,17]. Recent

prospective follow-up studies in patients following

HAART showed that, with successful viral suppression,

redistribution of T cells occurs, and results in an increase in

CD4 numbers both in the circulation and in the gut [18,19].

For those patients with a gut pathogen, activated memory

CD4 cells high in CD44 (a migratory adhesion molecule)

increase in the gut and improvements in villous height with

normalization of functional gut permeability, as measured

by sugar absorption tests, are seen [1820].

It is thought that after invasion of the enterocyte by

spore-forming protozoal organisms, the epithelial cells

release cytokines that activate the resident phagocytes and

recruit new phagocytes into the lamina propria from the

blood pool [21]. The activated leucocytes then release

2000 British HIV Association HIV Medicine (2000) 1, 194199

cytokines that increase the secretion of chloride and water,

and also inhibit absorption [21]. Research into the role of

cytokine production is currently ongoing. Previous studies

have shown that resolution of primary cryptosporidiosis in

the immunocompetent patient is associated with the

production of interleukin (IL)-15 by intra-epithelial lymphocytes. In previously sensitized individuals, re-infection

is associated with production of g-interferon and IL-4 by

lamina propria lymphocytes [22,23]. In follow-up studies

before and after HAART, expression of IL-15 g-interferon

and IL-4 were found to be absent prior to treatment, with

the reappearance of these cytokines following therapy [23].

The release of these cytokines from activated CD4 T-cell

lymphocytes in the gut may be important for the

eradication of opportunistic protozoal infections.

Alternative mechanisms for the cause of diarrhoea

includes functional motility abnormalities resulting from

HIV-induced autonomic neuropathy [24]. Patients with

protozoal infection have decreased intestinal transit times,

but it is unclear whether this is due to a primary motility

defect or results from malabsorption secondary to villous

atrophy [24].

Investigations

The most important investigation is stool analysis. Light

microscopy and culture of stool is required for routine

pathogens; however, special stains such as the modied

Ziehl-Nielsen [25], Calcouor [26] and trichrome stains

[27] should be requested for immunocompromised patients.

Stool light microscopy and culture are highly specic but

not particularly sensitive tests and therefore at least three,

and preferably six, different stool samples should be sent

for examination [6]. Newer polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) techniques are available, but these tests are costly

and time-consuming and therefore not routinely available

in hospital practice [28,29]. The sensitivity of PCR

techniques for both cryptosporidia and microsporidia

may be much better than currently available techniques.

In the case of cryptosporidia, the threshold for detection is

50 oocysts per gram of stool, compared to a threshold of

50 000 oocysts per gram of stool with routine light

microscopy [30,31]. For microsporidia the threshold for

PCR detection is 100 spores per gram of stool, compared

with light microscopy where the detection threshold is

between 104 and 106 spores per gram of stool [29]. Thus,

some of the individuals formerly diagnosed with pathogennegative diarrhoea may have been infected with these

organisms.

Gut biopsy is an important tool in the investigation of

diarrhoea. Ten per cent of those with cryptosporidial

infections may be detected by gut biopsy, despite stool

196 YM Miao and BG Gazzard

samples remaining negative [32]. Identication of microsporidia in the small bowel at light microscopy may be

difcult due to the intracellular nature of the organism and

its poor staining properties with routine histological stains.

Previously electron microscopy was the `gold standard' and

the only reliable method for species identication [33]. This

was particularly relevant as certain microsporidia species

(E. intestinalis) respond better to treatments such as

albendazole when compared to others [34]. PCR analysis

of either gut or stool samples can also help to identify the

type of microsporidia species that was undertaken previously by electron microscopy [35].

Endoscopic examination can also help to exclude other

more rare causes of diarrhoea seen in late-stage AIDS, such

as lymphomas, the frequency of which have been less

affected by the introduction of HAART [36].

Management of diarrhoea

For those patients presenting with diarrhoea as their initial

AIDS-presenting diagnosis, the most important goal is to

identify any treatable infections or neoplasms. History of

the illness may give valuable clues to the aetiology.

Patients with low-volume diarrhoea tend to resolve

spontaneously or can be controlled with antimotility

agents, a response that is also seen in patients with irritable

bowel syndrome [5].

In HIV-seropositive patients, the single most important

factor governing the severity of disease and prognosis is the

degree of immune suppression in individual patients. A CD4

count of above 200 cells/mL normally indicates that although

opportunistic infections such as cryptosporidiosis and

microsporidiosis can occur, they tend only to be transient

illnesses [37], with the immune system still being able to

eradicate the parasites through a cellular immune response.

For those with CD4 counts below 200 cellls/mL the

treatment of choice is initiation of HAART, but the

diagnosis of other associated pathogens with readily

available treatments is also important. Aside from cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis, HIV patients also have a

higher incidence of other gut pathogens, including

bacterial organisms such as salmonella and campylobacter;

atypical mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium aviumintracellulare (MAI); viral causes such as Cytomegalovirus

(CMV); other parasites such as giardia and amoeba; and

fungal infections such as candida.

In patients with advanced immunosuppression, prevention is better than cure. Simple advice to drink only boiled

water reduces exposure to cryptosporidiosis. Standard

ltration or chlorination processes are not effective in

eradicating these protozoa from water supplies [38].

Boiling drinking water for 12 min kills the organisms

and reduces the risk of infection [21]. Successful combination antiretroviral therapy is, however, the only treatment

available which has been shown to eradicate opportunistic

enteroparasites through a process of host-immune reconstitution [8,28].

In those patients who are acutely unwell through a

combination of fevers, dehydration and diarrhoea, quinolones such as ciprooxacin should be effective against

associated bacterial causes of diarrhoea. Supportive

measures with either oral or intravenous rehydration are

important to correct electrolyte imbalances quickly. For

those patients who do not respond to antiretroviral therapy,

symptomatic measures such as the liberal use of antidiarrhoeals (loperamide and codeine phosphate) and, in some

patients, opiates may be needed.

Treatment with subcutaneous somatostatin analogues

such as octreotide may help patients by reducing intestinal

motility and by blocking the secretory mechanism of

diarrhoea. These drugs work via inhibiting intestinal

secretion stimulated by calcium, AMP and GMP and

enhance water and electrolyte reabsorption [39]. Use of

somatostatin analogues can result in dramatic reductions

in stool volume, and in some patients help alleviate

symptoms of nocturnal incontinence, although randomized

controlled trials have shown only limited value. Newer

longer-acting somatostatin analogues, which require only

fortnightly or monthly injections, have made this option

easier to administer.

Specic therapies for cryptosporidia and microsporidia,

such as paromomycin [40] and albendazole [33,34], can

alleviate symptoms by reducing parasite load and reducing

stool volume; however, the organisms are not eradicated.

Recently newer antimicrosporidial agents such as the

water-insoluble antibiotic, fumagillin, have been used

successfully in the treatment of supercial keratitis

secondary to microsporidial infection [41]. However,

systemic use is limited by toxicity. TNP-470, a newer

semisynthetic analogue of fumagillin, is currently being

assessed in vitro [42]. Recent results suggest that these

newer agents can inhibit replication of microsporidia by up

to 70%; however, studies in vivo are still awaited [42]. To

date, no similarly promising compounds have been

identied against cryptosporidial infections. Discrepancies

between drug assays in vitro, in animal models and in

human trials still frustrate efforts to identify any effective

anticryptosporidial agents [43].

Other therapies such as human bovine colostrum [44]

and letrazuril [40] have been tried in the past. Although

they may have helped to reduce symptoms, they did not

effect a cure. Thalidomide has been used with some success

in alleviating diarrhoeal symptoms of microsporidial

infection [45]. It has a number of potential actions,

2000 British HIV Association HIV Medicine (2000) 1, 194199

Management of protozoal diarrhoea in HIV disease 197

including being a simple constipating agent, and it is also

thought to reduce tumour necrosis factor-a (TNF-a).

TNF-a is a pro-inammatory cytokine associated with

cachexia and is increased in stool samples of patients with

HIV-associated diarrhoea [46].

For isospora, which is a common cause of diarrhoea in

South America and a more rare cause of diarrhoea in

HIV-infected individuals, a course of cotrimoxazole may

eradicate the parasite. However, isospora recurrence is

common and secondary prophylaxis may be required,

particularly in those patients who fail to respond to

HAART [47]. Cyclospora has been reported in HIV

patients, but more commonly causes travellers' diarrhoea

and is prevalent in India. Patients respond to treatment

with cotrimoxazole [48]. For giardia or amoeba, standard

treatment with metronidazole or tinidazole should result in

the complete eradication of both parasites [49].

References

1 Crotty B, Smallwood RA. Investigating diarrhea in patients

with acquired immunodeciency syndrome. Gastroenterology

1996; 110: 296310.

2 Sharpstone D, Gazzard B. Gastrointestinal manifestations of

HIV infection. Lancet 1996; 348: 379383.

3 Blanshard C, Jackson AM, Shanson DC, Francis N, Gazzard BG.

Cryptosporidiosis in HIV-seropositive patients. Q J Med 1992;

85: 813823.

4 Palella FJ Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC et al. Declining

morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human

immunodeciency virus infection. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:

853860.

5 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Clinical

Practice and Practice Economics Committee. AGA technical

review on the evaluation and management of chronic

diarrhoea. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 14641486.

Summary

Refractory diarrhoea secondary to opportunistic protozoal

pathogens has become less of a problem in HIV-infected

individuals since the widespread use of combination

antiretroviral therapy. Pathogens such as cryptosporidia

and microsporidia are now rare causes of diarrhoea in HIVinfected individuals. Nowadays, these conditions are rarely

seen in HIV individuals routinely followed-up in clinic, as

they tend to be treated with HAART before the CD4 count

falls below 200 cells/mL. However, these pathogens may

still cause signicant pathology in those where the HIV

status is unknown, especially in those patients presenting

with diarrhoea as their initial AIDS-presenting diagnosis.

The majority of these patients have CD4 counts below 200

cells/mL. In those affected, the only treatment available is

HAART which, if successful, suppresses viral replication

and results in reconstitution of the immune system leading

to eradication of previously untreatable parasites. Immune

reconstitution may take up to 6 months to be effective and

therefore, while a response is awaited from HAART,

symptomatic measures such as antidiarrhoeals, uid

replacement and enteral supplements may still be required.

For patients with high-volume diarrhoea, specic measures

such as albendazole, paromomycin or subcutaneous

octreotide may be useful in reducing symptoms while

awaiting a response from HAART. It is important to

remember that HAART results in suppression but not

eradication of the human immunodeciency virus, and

therefore life-long therapy is required [50,51]. Those

individuals who fail therapy, as a result of emerging viral

resistance or as a failure of drug compliance, will remain

prone to re-infection and hence continued vigilance is

required.

2000 British HIV Association HIV Medicine (2000) 1, 194199

6 Blanshard C, Francis N, Gazzard BG. Investigation of

chronic diarrhoea in acquired immunodeciency syndrome.

A prospective study of 155 patients. Gut 1996; 39:

824832.

7 Anonymous. Cryptosporidium in water supplies: the second

Badenoch report. Communicable disease report. CDR Weekly

1995; 5: 245248.

8 Miao YM, Awad-El-Kariem FM, Franzen C et al. Eradication of

cryptosporidia and microsporidia following successful antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Dec Syndr 2000; in press.

9 Flanigan T, Whalen C, Turner J et al. Cryptosporidium infection

and CD4 counts. Ann Intern Med 1992; 116: 840842.

10 Manabe YC, Clark DP, Moore RD et al. Cryptosporidiosis in

patients with AIDS. Correlates of disease and survival. Clin

Infect Dis 1998; 27: 536542.

11 Lim SG, Menzies IS, Lee Ca, Johnson MA, Pounder RE.

Intestinal permeability and function in patients with human

immunodeciency virus. Scand J Gastroenterol 1993; 28:

573580.

12 Bjarnson I, Sharpstone DR, Francis N et al. Intestinal

inammation, ileal structure and function in HIV. AIDS 1996;

10: 13851391.

13 Schneider T, Jahn HU, Schmidt W et al. Loss of CD4 T

lymphocytes in patients infected with human

immunodeciency virus type 1 is more pronounced in the

duodenal mucosa than in peripheral blood. Gut 1995; 37:

524529.

14 Snijders F, Meenan J, Van Den Blink B, Van Deventer SJH, Ten

Kate FJW. Duodenal intraepithelial and lamina propria T

lymphocytes in human immunodeciency virus-infected

patients with and without diarrhoea. Scand J Gastroenterol

1996; 31: 11761181.

15 MacDonald TT, Spencer J. Evidence that activated mucosal

198 YM Miao and BG Gazzard

T-cells play a role in the pathogenesis of enteropathy in human

clinical stool specimens. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1999; 6:

small intestine. J Exp Med 1988; 167: 13411349.

16 Goodgame RW, Kimball K, Ou CN et al. Intestinal function

243246.

30 Weber R, Bryan RT, Bishop HS, Wahlquist SP, Sullivan JJ,

and injury in acquired immunodeciency syndrome-related

Juranek DD. Threshold of detection of cryptosporidium oocysts

cryptosporidiosis. Gastroenterology 1995; 108: 10751082.

in human stool specimens: evidence for low sensitivity of

17 Schmidt W, Schneider T, Heise W et al. Mucosal abnormalities

in microsporidiosis. AIDS 1997; 11: 15891594.

18 Hayes PJ, Miao YM, Gotch FM. Gazzard BG. Alterations in

current diagnostic methods. J Clin Microbiol 1991; 29:

13231327.

31 Balabat AB, Jordan GW, Tang YJ, Silva J Jr. Detection of

blood leucocyte adhesion molecule proles in HIV-1 infection.

Cryptosporidium parvum DNA in human feces by nested PCR.

Clin Exp Immunol 1999; 117: 331334.

19 Miao YM, Hayes PJ, Gotch FM, Gazzard BG. Lymphocyte

J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34: 17691772.

32 Gazzard B. Weight loss and diarrhoea. In: Gazzard B, ed.

migration to the gut in HIV infection and HAART. 6th Annual

Chelsea & Westminster Hospital AIDS Care Handbook. London,

Conference of the British HIV Association [BHIVA].

Edinburgh. March 2000 (abstract P46).

20 Miao YM, Bjarnson I, Crane R, Hayes PJ, Gazzard BG.

Mediscript Ltd, 1999: 201214.

33 Leder K, Ryan N, Spelman D, Crowe S. Microsporidial disease in

HIV-infected patients: a report of 42 patients and review of the

Normalization of intestinal permeability in AIDS following

successful antiretroviral therapy. 6th Annual Conference of the

literature. Scand J Infect Dis 1998; 30: 331338.

34 Weber R, Sauer B, Sprycher MA et al. Detection of Septata

British HIV Association [BHIVA]. Edinburgh. March 2000

intestinalis in stool specimens, and coprodiagnostic monitoring

(abstract O13).

of successful treatment with albendazole. Clin Infect Dis 1994;

21 Goodgame RW. Understanding intestinal spore-forming

19: 242245.

protozoa: cryptosporidia, microsporidia, isospora, and

35 Franzen C, Muller A. Molecular techniques for detection,

cyclospora. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124: 429441.

22 Culshaw RJ, Bancroft GJ, McDonald V. Gut intraepithelial

species differentiation, and phylogenetic analysis of

microsporidia. Clin Microbiol Rev 1999; 12: 243285.

lymphocytes induce immunity against cryptosporidium

36 Ledergerber B, Telenti A, Egger M. Risk of HIV-related Kaposi's

infection through a mechanism involving gamma interferon

sarcoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with potent

production. Infect Immun 1997; 65: 30743079.

antiretroviral therapy: prospective cohort study. Swiss HIV

23 Okhuysen PC, Robinson P, Lewis DE et al. Sequential

expression of IL-15, Interferon gamma, and IL-4 in

Cohort Study. BMJ 1999; 319: 2324.

37 Neild PJ, Nelson MR. Management of HIV-related diarrhoea.

cryptosporidiosis patients during immune reconstitution with

HAART. 7th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic

Infections. San Francisco. January 2000 (abstract 263).

Int J STD AIDS 1997; 8: 286297.

38 Korich DG, Mead JR, Madore MS, Sinclair NA, Sterling CR.

Effects of ozone, chlorine dioxide, chlorine, and

24 Sharpstone D, Neild P, Crane R et al. Small intestinal transit,

monochloramine on Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability.

absorption, and permeability in patients with AIDS with and

without diarrhoea. Gut 1999; 45: 7076.

Appl Environ Microbiol 1990; 56: 14231428.

39 Romeu J, Miro JM, Sirera G et al. Efcacy of octreotide in the

25 Garcia LS, Bruckner DA, Brewer TC, Shimizu RY.

management of chronic diarrhoea in AIDS. AIDS 1991; 5:

Techniques for recovery and identication of

cryptosporidium oocysts from stool specimens. J Clin

14951499.

40 Blanshard C, Shanson Dc Gazzard BG. Pilot studies of

Microbiol 1983; 18: 185190.

26 Vavra J, Dahbiova R, Hollister WS, Canning EU. Staining of

microsporidian spores by optical brighteners with remarks

azithromycin, letrazuril and paromomycin in the treatment of

cryptosporidiosis. Int J STD AIDS 1997; 8: 124129.

41 Coyle C, Kent M, Tanowitz HB, Wittner M, Weiss LM. TNP-470

on the use of brighteners for the diagnosis of AIDS

is an effective antimicrosporidial agent. J Infect Dis 1998; 177:

associated human microsporidiosis. Folia Parasitol 1993; 40:

515518.

267272.

42 Didier ES, Nasr M, Leblanc J, Bertucci DC, Phillips J, Didier

27 Ryan NJ, Sutherland G, Coughlan K et al. A new trichrome-

PJ. Antimicrosporidial effects of the sequiterpenes,

blue stain for detection of microsporidial species in urine, stool,

fumagillin, TNP-470, and eight ovalicin derivatives in vitro

and nasopharyngeal specimens. J Clin Microbiol 1993; 31:

32643269.

and in vivo. 7th Conference on Retroviruses and

Opportunistic Infections. San Francisco. JanuaryFebruary

28 Miao YM, Awad-El-Kariem FM, Gibbons CL, Gazzard BG.

Cryptosporidiosis: eradication or suppression with combination

2000 (abstract 262).

43 Awad-El-Kariem FM. Does Cryptosporidium parvum have a

antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 1999; 13: 734735.

clonal population structure? Parasitol Today 2000; 15:

29 Muller A, Stellermann K, Hartmann P, et al. A powerful DNA

extraction method and PCR for detection of microsporidia in

502504.

44 Nord J, Ma P, DiJohn D, Tzipori S, Tacket CO. Treatment with

2000 British HIV Association HIV Medicine (2000) 1, 194199

Management of protozoal diarrhoea in HIV disease 199

bovine hyperimmune colostrum of cryptosporidial diarrhea in

Cyclospora infection in adults infected with HIV. Clinical

AIDS patients. AIDS 1990; 4: 581584.

manifestations, treatment and prophylaxis. Ann Intern Med

45 Sharpstone D, Rowbottom A, Francis N et al. Thalidomide: a

49 Trier JS, Moxey PC, Schimmel EM, Robles E. Chronic intestinal

in Gastroenterology 1997; 113: 1054]. Gastroenterology 1997;

coccidiosis in man: intestinal morphology and response to

112: 18231829.

46 Sharpstone DR, Rowbottom AW, Nelson MR, Lepper MW,

treatment. Gastroenterology 1974; 66: 923935.

50 Zanders JJ, Cunningham PH, Kelleher AD, et al. Potent

Gazzard BG. Faecal tumour necrosis factor-alpha in

antiretroviral therapy of primary human immunodeciency

individuals with HIV-related diarrhoea. AIDS 1996; 10:

virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection: partial normalization of T

989994.

lymphocyte subsets and limited reduction of HIV-1 DNA

47 Pape JW, Verdier RI, Johnson WD Jr. Treatment and

prophylaxis of Isospora belli infection in patients with the

acquired immunodeciency syndrome. N Engl J Med 1992;

320: 10441047.

48 Pape JW, Verdier RI, Boncy M, Boncy J, Johnson WD Jr.

1994; 121: 654657.

novel therapy for microsporidiosis [published erratum appears

2000 British HIV Association HIV Medicine (2000) 1, 194199

despite clearance of plasma viremia. J Infect Dis 1999; 180:

320329.

51 Sharkey ME, Teo I, Greenough T et al. Persistence of episomal

HIV-1 infection intermediates in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nature 2000; 6: 768152.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- 675 Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment A Research Based Guide Third EditionDocument75 pages675 Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment A Research Based Guide Third EditionVivek VatsNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The LGBT Movements Health Issues - Higher Rates of HIV/AIDS and Other STDs Among LGBT MembersDocument127 pagesThe LGBT Movements Health Issues - Higher Rates of HIV/AIDS and Other STDs Among LGBT MembersAntonio BernardNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Teenage PregnancyDocument2 pagesTeenage PregnancyKedi BoikanyoNo ratings yet

- PRE MS N2016 Ans KeyDocument33 pagesPRE MS N2016 Ans Keyaaron tabernaNo ratings yet

- BIO CBSE 12 PROJECT On HIV/AISDocument15 pagesBIO CBSE 12 PROJECT On HIV/AISAnonymous KdUrkMIyJQ73% (56)

- Accreditation Of: Health Care SystemDocument44 pagesAccreditation Of: Health Care SystemFedelyn Mae AcaylarNo ratings yet

- Teaching Medicine and Medical Ethics Using PopularDocument180 pagesTeaching Medicine and Medical Ethics Using PopularRizky AmaliahNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan ON Congenital SyphilisDocument19 pagesLesson Plan ON Congenital SyphilisRenuga SureshNo ratings yet

- UNICEF Presentation on Its Role & Child Protection InitiativesDocument16 pagesUNICEF Presentation on Its Role & Child Protection InitiativesKrishnaveni MurugeshNo ratings yet

- PPMP Directional Plan 2017-2022 Questions ReviewedDocument10 pagesPPMP Directional Plan 2017-2022 Questions ReviewedCecilia-Aint JaojocoNo ratings yet

- Association Between Smoking Behavior and LDLDocument1 pageAssociation Between Smoking Behavior and LDLSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- 55 259Document6 pages55 259Sri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Weight-For-Age GIRLS: 2 To 5 Years (Z-Scores)Document1 pageWeight-For-Age GIRLS: 2 To 5 Years (Z-Scores)Gibson HorasNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument1 pageDaftar PustakaSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- VancouverDocument11 pagesVancouverAndi Firman MubarakNo ratings yet

- Nkcells Further ReadDocument1 pageNkcells Further ReadSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine Bleeding: Frequently Asked Questions FAQ095 Gynecologic ProblemsDocument3 pagesAbnormal Uterine Bleeding: Frequently Asked Questions FAQ095 Gynecologic ProblemsErwinNo ratings yet

- Cover Skripsi Bahasa InggrisDocument1 pageCover Skripsi Bahasa InggrisSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome in Adults 2009Document6 pagesNephrotic Syndrome in Adults 2009Mutiara RizkyNo ratings yet

- Alcohol 10 QuestionnaireDocument1 pageAlcohol 10 Questionnaireyash_magooNo ratings yet

- 0709Document4 pages0709Sri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Frequency of Renal Stone Disease in Patients With Urinary Tract InfectionDocument3 pagesFrequency of Renal Stone Disease in Patients With Urinary Tract InfectionSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Management of Protozoal Diarrhoea in HIV DiseaseDocument6 pagesManagement of Protozoal Diarrhoea in HIV DiseaseSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

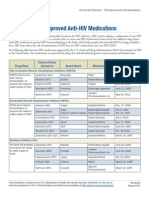

- ApprovedMedstoTreatHIV FS enDocument2 pagesApprovedMedstoTreatHIV FS enSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Eur Heart J 2003 Fröhlich 1365 72Document8 pagesEur Heart J 2003 Fröhlich 1365 72Sri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Afroz - Lipid ProfileDocument6 pagesAfroz - Lipid ProfileSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Human Recombinant Erythropoietin On Prevention of Anemia of PrematurityDocument6 pagesThe Effect of Human Recombinant Erythropoietin On Prevention of Anemia of PrematuritySri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Uroanalisis AnormalDocument13 pagesUroanalisis AnormalMyke EstradaNo ratings yet

- Dysuria in AdultsDocument8 pagesDysuria in AdultsSi vis pacem...No ratings yet

- Difco BBL Mueller Hinton Agar BrothDocument5 pagesDifco BBL Mueller Hinton Agar BrothSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Uroanalisis AnormalDocument13 pagesUroanalisis AnormalMyke EstradaNo ratings yet

- Frequency of Renal Stone Disease in Patients With Urinary Tract InfectionDocument3 pagesFrequency of Renal Stone Disease in Patients With Urinary Tract InfectionSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- ResourceDocument5 pagesResourceSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Corrections: Theodore J. Cicero, Ph.D. Matthew S. Ellis, M.P.EDocument1 pageCorrections: Theodore J. Cicero, Ph.D. Matthew S. Ellis, M.P.ESri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Corrections: Theodore J. Cicero, Ph.D. Matthew S. Ellis, M.P.EDocument1 pageCorrections: Theodore J. Cicero, Ph.D. Matthew S. Ellis, M.P.ESri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Niacin MOADocument3 pagesNiacin MOASri Nowo Minarti100% (1)

- EpoDocument15 pagesEpoSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Etiology and Evaluation of Diarrhea in AIDS: A Global Perspective at The MillenniumDocument10 pagesEtiology and Evaluation of Diarrhea in AIDS: A Global Perspective at The MillenniumSri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Am J Clin Nutr 2008 Kupka 1802 8Document7 pagesAm J Clin Nutr 2008 Kupka 1802 8Sri Nowo MinartiNo ratings yet

- Passmrcog Micro2016Document130 pagesPassmrcog Micro2016Cwali MohamedNo ratings yet

- Invitation LetterDocument1 pageInvitation LetterAngelo SinfuegoNo ratings yet

- Internalized Homophobia and Health Issues Affecting Lesbians and Gay MenDocument11 pagesInternalized Homophobia and Health Issues Affecting Lesbians and Gay Menushha2No ratings yet

- Requirements For An Open-Source Pharmacy Dispensing and Stores Management Software Application For Developing CountriesDocument14 pagesRequirements For An Open-Source Pharmacy Dispensing and Stores Management Software Application For Developing CountriesGFBMGFBLKNGMDSBGFNFHNFHNMHDNo ratings yet

- Fractals reveal insights into human biologyDocument5 pagesFractals reveal insights into human biologykavithanakkiran_3003No ratings yet

- Hepatitis CDocument42 pagesHepatitis Cciara sandovalNo ratings yet

- 05b HIV Testing and Counseling (National)Document26 pages05b HIV Testing and Counseling (National)AIDSPhilNo ratings yet

- Demographic Health Health SurveysDocument18 pagesDemographic Health Health SurveysERUSTUS WESANo ratings yet

- Namibia Flipchart Algorithm Child Sep2010Document11 pagesNamibia Flipchart Algorithm Child Sep2010Gabriela Morante RuizNo ratings yet

- Health: " Finally, A Medical Plan That Rewards Us For Being Healthy, and Covers Us When We Are Not! "Document7 pagesHealth: " Finally, A Medical Plan That Rewards Us For Being Healthy, and Covers Us When We Are Not! "stewartyeeNo ratings yet

- Translate UsuDocument8 pagesTranslate UsuGhina SalsabilaNo ratings yet

- Radical Philosophy 156 PDFDocument68 pagesRadical Philosophy 156 PDFkarlheinz1No ratings yet

- Ss. 11. Dr. Dhani R. Sepsis Hiv3Document43 pagesSs. 11. Dr. Dhani R. Sepsis Hiv3budi darmantaNo ratings yet

- Prevention of HerpatitisDocument54 pagesPrevention of Herpatitisapi-270822363No ratings yet

- Zubeda First Draft ThesisDocument96 pagesZubeda First Draft ThesisBereketNo ratings yet

- Chapter 21 - Aids2Document31 pagesChapter 21 - Aids2Sanjeevan Aravindan (JEEV)No ratings yet

- Gold and Nanotechnology in The Age of InnovationDocument24 pagesGold and Nanotechnology in The Age of InnovationGoldGenie AsiaNo ratings yet

- World Bank HIV/AIDS Program Development Project (II) in Nigeria, An Exploration of TB and TB/HIV OptionsDocument29 pagesWorld Bank HIV/AIDS Program Development Project (II) in Nigeria, An Exploration of TB and TB/HIV OptionsChukwu JanefrancesNo ratings yet

- 111 Laporan Kasus ToxoplasmosisDocument33 pages111 Laporan Kasus ToxoplasmosisLouis MailuhuNo ratings yet

- What Is Holding Back The Fight Against HIV/AIDS?: TimesDocument24 pagesWhat Is Holding Back The Fight Against HIV/AIDS?: TimesJohnson KwizeraNo ratings yet