Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tha Plantation As A Social System

Uploaded by

Nithin KalorthOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tha Plantation As A Social System

Uploaded by

Nithin KalorthCopyright:

Available Formats

The Plantation as a Social System

Author(s): Sharit Kumar Bhowmik

Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 15, No. 36 (Sep. 6, 1980), pp. 1524-1527

Published by: Economic and Political Weekly

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4369053 .

Accessed: 02/02/2015 02:14

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Economic and Political Weekly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 59.90.82.87 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 02:14:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The

Plantation

as

Social

System

Sharit Kumar Bhowmik

The plantation has a distinct form of production organisation which gives rise to certatin specific

social relations. Most definitions of a plantation tend to overlook these relations which emerge from the

plantation as a social system.

This paper, based on the findings of fieldwork conducted among tea plantation workers in the

Dooars in North Bengal, attempts a sociological definition of the plantation system. The uniqueness of a

plantation system lies in its social and production relNtions. These no doubt have changed since the days

of pla;ntation economies of colonial times and are chaiging even now; but the change in these relations is

determined by the context of isolation of the plantantion from the wider social system, the influence of the

working class organisations among the workers and the role of the State.

TI-IE plantation has a distinct form of

gives

which

organisation

production

rise to certain specific social relations.

Most writers, while defining a plantathese relations

t$on, tend to overlook

which emerge from the plantation as a

its

social system. They either explain

production relations or they deal with

the production unit itself. In this paper

I have tried to show the inadequacies

of such definitions and have attempted

ar. alternative sociological definition of

the plantation system.

The paper is based on the findings of

my field investigation conducted among

the tea plantation workers in the Dooars

are in jalpaiguri district, West Bengal.

A majority of the workers employed in

Adivasis

plantations are

the Dooars

(Scheduled Tribes) from the Chotanagpur area of Bihar. They mainly belong

to the Oraon, Mtunda, Kharia and Santhal tribes. These workers were brought

to the Dooars at the end of the nineteenth century as indentured labour in

up

the tea plantations which sprang

cluring this time. The first tea garden

wvas founded here in 1874. At present

the tea growing area stretches to nearly

200 kilometres in length and around 50

kilometres in breath and comprises

152 tea gardens which account for a

little less than 20 per cent of India's

tea produ-iction. The labour force in the

tea gardens has settled in and around

the plantations and has little or no

contact with their places of origin.

SOME DEFNTIONS

Labour OrganisalThe International

tion1 notes that the term plantation at

first referred to a group of settlers, or

the political unit formed by it, under

British colonialism, specially in North

America and in the West Indies. However, with the colonisation of African and

Asian regions hy British and European

a broader

it acquired

entrepreneurs,

connotation and came to denote largescale enterprises

in agricultural units

and the development of certain agricultulral resources of tropical countries in

accordance with the methods of western

Hla Myint2 distinguishes the

industry.

plantation from peasant agriculture by

its large-scale enterprise which normally

requires more labour per unit of land.

William 0 joanes3 defines a plantation

as "an economic unit producing agriculand

sale

commodities... for

tural

employing a relatively large number of

un.skilled labourers whose activities are

from

supervised... [it differs]

closelv

other kinds of farms in the way in

of production, priwxhich the factors

marily management and labour are comhierarchy

bined." There is a vertical

with skilled superin the plantation

visors or managers directing production

uindertaken by unskilled labourers whose

"primary skill is to follow orders".

Historically, plantations were a product of colonialism. Their produce was

mainly for export. In some cases such

they were

as rubber and cinchona,

established to provide raw material for

for the

especially

western industry In others, such as

colonising country.

tea, coffee and sugar, their markets lay

colonising countries.

in the developed

The growth of tea plantations in India

was a result of a rise in popularity of

Indian tea in Britain: Indian tea scored

over Chinese tea, which was popular in

the early nineteenth century, because of

its thicker brew.4 Hence plantations in

the colonies were fundamentally international in character.

The development of plantations necessitated two basic requisites: large area

of cultivable

land

and, secondly, a

large labour force. However, the areas

most suited for plantations were initially

Hence, during the

sparsely populated.

faced the

formative years, plantations

problem of acute labour shortage. They

had to depend on migrant labour whose

mnigration had to be induced by the

planters. One can cite the examples of

America,

cotton plantations in North

stugar in British Guyana and Cuba,

ruibberin Malaya and tea in India. All

these plantations depended on migrant

labour. The early plantations in America

and the Caribbean Islands were run on

slave labour. After the abolition of

slavery, indenture became a common

mnode of recruitment. We therefore

find that the plantation came to be associated not only with a resident labour

force but, more often than not, "with

one of alien origin".5

SPECIFIC

FEATUREs

OF

PLANTAIION

SYSTE

In defining the plantation a mere

description of its economic features, as

Myint has done, or simply dealing with

the production unit itself, as Jones has

done, are not sufficient. A sociological

definition of the plantation cannot be

restricted to an enumeration of some

characteristic features such as scale of

production, single crop pattern, export

oriented market, immigrant labour, and

so on. These features may be common

in plantation systems all over the world

b)ut they describe, rather than define,

the plantation system.

Such descriptions overlook two vital

aspects which are important for understanding the production relations. Fitst,

how the prevalent production relations

emerge in a plantation; and secondly,

as the plantation is a part of the wider

social system, a change in that will cause

a change in the prevailing production

rielations.

In this regard, Eric Wolf takes a

broader approach. He points out that

the establishment of plantations has

always destroyed the antecedent cultural

uorms of the area concerned. Wolf

states that the plantation "is also an

instrument of force wielded to create

anid to maintain a class-structure of

workers and owners, connected hierarchically by a staff line or overseers and

The point to be emphasised

rmanagers".6

here is that coercion is an integral part

1524

This content downloaded from 59.90.82.87 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 02:14:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL

September 6, 1980

WEEKLY

of the plantation system. It results from

the nature of production relations in it.

The main limitation of Wolf's definition

is that it covers just one phase. of the

plantation

system.

Coercion

is an

integral

part of this system

but it

gradually diminishes. In order to understand whv this happens we must investigate the relations of production in thb

plantation system and how it changes.

The plantation is a labour intensive

industry.

At the same time, as noted

earlier, the most suitable places for the

establishment of plantations were areas

where labour supply was sparse. A high

wage rate could possibly have induced

workers to migrate to these areas, but

the planters

were not willing to pay

their workers well. Hla Myint notes that

the wages the planters paid were very

low, and they "tended to stick at their

initial level in spite of rapid expansion in

the production of ... plantation exports".7

Myint tries to justify this phenomenon

bv arguing that since

productivity of

labour was low, the wage rate also had

to be low. Under these circumstances,

an increase in the wage rate, so as to

attract more workers, would mean that

current wages would

be higher than

the short-run productivity of labour. In

the long-run,

however, productivity nf

labour would rise as health of the

workers would improve as a result of

wvelfare measures.8

However, Myint's argument is not

very convincing.

First, the wage rate

remained static even after productivity

of

labour

increased

significantly.

Secondly, in these same colonies, labour

Nvas attracted through higher wages in

non-plantation industries. For instance,

in 1883, in spite of the fact that the tea

plantations in Assam were facing acute

4,bour shortage, the average income of

the tea garden worker remained static

at Rs 3 per month.9 During the same

period wages of textile

workers

in

Bombay rose from Rs 7-12-0 per month

in 1860-62 to Rs 13-12-0 per month in

188.3, because the rapidly expanding industry was facing a shortage of labour.'0

Wages in the tea plantations were not

only much lower than wages in other

iridustries, but they

were also lower

than the wages of

agricultural labour

in the neighbouring areas.

The SubDivisional Officer of Karimganj wrote in

1883 that while the wage rate of the

emigrant plantation worker remained at

]Rs 3 per month "Bengalis in the adjoining villages earned without

difficulty

The wage

rupees seven per month"."

rate of the plantation workers in the

Dooars was simnilar to that in Assam.'2

W W Hunter noted that the wages for

day labourers or agricultural labourers

in Jalpaiguri district were around three

annas to four annas per day (around

seven rupees per month) in 1872,13 i e,

the first tea garden

two years before

was estab)lished in this district.

In reality the productivity of plantation labour was never a major consideration in determining the wage rate.

There existed a duialism in the plantation svstem. The plantation in its relation to the outside world was govemed

by the market principle, ie, the price

of its products was fixed through the

interaction of demand and supply. At

the same time, its own internal hierarchy

For inregulated by coercion.

was

stance. in the tea industry, the wages

workers were fixed

of the plantation

by the planters through their organisaIndian Tea Association.

tions like the

the Indian Tea Planters Association and

others. The workers had no say in the

matter. This is why the Royal Comin 1930, strongly

mission on Labour,

recommended that a wage fixing mnachinery be established in the tea induistrv,

even thouigh the planters felt that fixing

"absoluitely

of minimuim wages was

unnecessary".14 The Rage Commission

made a similar recommendation in 1944

in view of the fact that the workers had

not developed a spirit of collective bargaining and hence thev could not take

in bargaining for fair

a uinified stand

wages.'5

and immigrant

Coercion, low wages

labour were initially the three important,

or rather, inseparable, components

of

the plantation system.

These ensured

The

the planters their high profits.

plantation, being a labour-intensive ina reduction in the wage bill

dustrv,

same

At the

would increase profits.

able to

time the planters should be

have a captive labour force and extract

as much work as possible from the labourers. Employment of indentured or

slave labour ensured

for the planters

that the workers were bound to work

on the plantations

on whatever wage

In this way the

was given to them.

the

to obstruct

were able

planters

market and the

of a labour

growth

workers

of a market

were deprived

wage. In the normal course, when the labour market is relatively free, the market

wage is determined by the demand for,

and supply of, labour. When there is a

shortage of labour, wages rise in order

to attract more workers to the market.

This is what happened in the Bombay

textile industry. However, in the plantations we find that the wage rate was

not only static but it was even lower

than the wage rate of the local agricultural workers.

If at all local labour was used, the

planters made sure that they depended

only on the plantation as their means

of sustenance. For instance, in the

Caribbean countries, the entire peasantry was uprooted from land so as to

provide labour for the sugar plantations.16S W Mintz mentions a similar

situation in Puerto Rico where the

sugar plantation owners procured their

labour by coercion. The planters used

both slave labour and the local population as sources of labour supply. The

Governor General of Puerto -Rico issued

an order in 18.37 compelling "all landless workers to go to work on local

plantations and to register their names

in municipal rolls, under penalty of

fines".17

In the initial stages of the plantation

industry in India, the government adopted a position which favoured the

planters. The Assam planters, in a bid

to overcome their shortage of labour,

sought to uproot the local peasants from

their lands. They appealed to the government to increase land revenue so

that the peasantry around the plantation areas would give up their lands

and seek work in the plantations.

Consequently, in 1868, the Bengal

government double the land revenue rates in those areas. This did

not have the intended effect as the peasants rose in protest and refused to pay

the enhanced rates.18The planters then

resorted to the system of indenture.

Becruiters roamed the Chotanagpur

area to enlist impoverished tribals for

work in the plantatlons. These people

wverelured by false promises of a better

life. They had to enter into a contract

with their employers which laid down

that they would have to work for a

minimum of four years.

Isolation and an almost complete absence of legal protection had placed the

plantation worker in a position of total

dependence. These prevented the

worker from migrating elsewhere for

better wages. The planters, on the

other hand, enjoyed full protection from

their respective governments, as it was

n)oted earlier. For example, the plantation worker in Assam had no right to

leave the plantation even if he found

that conditions there were different from

those he had been promised. The planters had the Workmen's Breach of Contract Act'9 to prevent any worker from

leaving before his contract period was

over.

In the Dooars,

the conditions

1525

This content downloaded from 59.90.82.87 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 02:14:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

September 6, 1980

ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY

even though the

were almost similar

Workmen's Breach of Contract Act was

not enforced there, though the planters

occasionally thought of extending it in

their area, as is evident from the reports of the Dooars Planters' Association

for the years 1921 and 1937. However,

the planters employed guards to keep

and prevent

on their labour

an eye

Also, the isolation

them from leaving.

of the Dooars area prevented the worIt

kers from leaving the plantations.

was virtually impossible for any worker

to find his way back to Chotanagpui

once he was in the Dooars.

Thus we find that the planters were

able to maintain the plantation system

main factors:

coercion,

duie to four

and political

migrant labour, isolation

suipport. However, a definition of the

plantation system based on these four

The

points is still not comprehensive.

plantation system is not a static system.

Irn order to understand the change in

this system it is necessarv to analyse its

and its linkage

relations of production

tc the wider social system.

PLAN-TATION

AND Socio-ECONOMIC

SYSTE

The plantation is a component of the

The factors

socio-economic formation.

think are inherent in the

wvhich we

plantation system are in fact allowed to

by the larger

exist, or are protected,

socio-economic system. The production

relations in the plantation svstem change

in the wider

when there is a change

socio-economic formation.

Cuba is a 'plantation

For instance,

economvy having the superficial characteristics of other plantation economies.

revolution in 1959,

However after the

changed.

system

the

socio-economic

sugar is still the main

Even though

crop, the absence of foreign ownership

and the change in the social and class

structure shows that Cuba cannot be

plantation econoequated with other

mies in the region such as Haiti or

Banana ReGuatemala or any of the

Prior to

of Central America.

publics

1959, the Cuban sugar plantations also

lbad coercion, low wages and all the inherent features of a plantation system.

as the

have changed

These features

ownership of the plantations passed

from private owners into the hands of

the State.

In India too, though tea production

began with all the features of a classical plantation system, the change in the

State after indepencharacter of the

dlence has been affecting this system.

Hence, thotugh plantations are historically linked with colonialism, they are

not struictturallv, or inevitably,

linked

As these colonies free themwvith it.

selves and hecorne

independent countries, a new set of production relations

springs up.

Political pressures are increasinglv mounted on the government

to pass laws protecting the plantation

wvorker and

giving him a degree of

security

in his work.

Conditions for

the growth

of workers' organisations

develop, which

in turn encourage the

plantation workers to fight for better

conditions of work. The use of coercion

is relaxed and the isolation of the plantation is broken down.

In the Dooars, apart from protection

granted by the govemment in the form

of laws (such as the Industrial Disputes

Act, Minimum

Wages Act, Plantation

Labour Act, etc), improvement in commuinications helped the workers in orIt helped

ganising themselves.

break

clown their isolation and brought them

in contact with the world outside the

plantation system.

The old plantation

system could ruin successfullv as long as

the workers remained out of touch with

system and remained

the wider social

uInorganised and at the

mercy of the

The more the workers came

planters.

in contact with the wider social system.

the faster was the pace of their social

emancipation.

Earlier, the planters got the support

of the government in passing laws in

their favour.

Thev were

uinited and

economically powerful. The Rege Commission had

noted that

the planterv

were "highly organised and powerful"

and their associations

played a vital

role in deciding

all issues affecting

labour; on the other hand, the workers

were "all unorganised

and helpless".20

once the

However,

workers

started

for

organising themselves and fighting

their basic rights, they challenged this

power of the planters. They compelled

the government to modifv many of the

laws

the

which favoured

stringent

planters at the expense of the workers.

The change in the plantation system in

all parts of the world started when

plantation labour united to fight for its

rights and influence the affairs of the

State.

such as India,

In

some countries,

from

plantation labour also benefited

other sections of the

the struggles of

working class. In the initial post-indelabour in

plantation

pendence stage,

of laws which

India got the benefits

granted

protection to workers, mainly

because

of the

struggles

of other

sections of the working class which had

pressurised

the

government

to pass

these laws.

Later, as a result of this

protection, or, we can say, encouraged

by it, it was able to organise struggles

for its own rights.

CONCLUSION

The socio-economic formation of the

plantation industry, with its low level of

technology and its heavy dependence on

rrianual laboiir, is significantly diffetent

frorm that of other

industries. The

general isolation of the plantations and

its dependence on

immigrant labour

give rise to some specific characteristics

to its labour force. The social relations

among the workers which evolves out

of such system

is also bound

to be

different from that of labour in other

industries. In the Dooars, the production

rielations into which the tribal workers

enter give them the objective charactetistics of induistrial workers as they are

wage labouir selling their labour power.

However, isolation

tends to help the

workers preserve their links with their

social organisation. Hence they

carry

forward

from their tribal background

some of the social and cultural characteristics associated with a totally different

kind of production system.

Therefore,

while attempting to define the plantation

system, an elucidation of its economic

characteristics is not enough.

It does

not explain the uniqueness of the plantation.

The social relations,

and the

production relations which spring forth

from such

a system, are

important

characteristics of the plantation. Secondly, the possibility

of change in such

relations is determined by the extent of

isolation of the plantation from the wider

social system., the influence of working

,class organisations among the workers

and the role of the State.

Notes

[I am grateful to Andre Beteille for his

comments and criticism.]

I International Labour Organisation,

"Basic Problems of Plantation Labouir", Geneva, 1950, pp 6-9.

2 Hla Myint,

"The Economics

of

Developing

Countries",

London,

1973, p 40.

0

3 William

Jones,

'Plantation'

International Encyclopaedia of Social Sciences, 1968, pp 154-56.

Hugh Tinker, "A New System of

Slavery: The

Export of

Indian

Labour Overseas, 1830-1920", LondIon, 1974, p 29.

I Greaves, 'Plantations

in World

Economy' in "Plantation Systems of

the New World", Washington, 1959,

p 115.

1526

This content downloaded from 59.90.82.87 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 02:14:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL

WEEKLY

September 6, 1980

Tea Planters' Association,

Indian

in the attemnptto economise the pubAinnual General Report, Jalpaiguri, lic expenditure. We have some evi1929, p 98. This was in reply to a

dence in this regard from the review

(ltiestionnaire circulated by the Romade by the Comptroller and Auditorin

India.

yal Commission on Labour

7

('On Improving

General of India.

15 D V Rege, "Report on an Enquiry

8

in Effectiveness of Govemment Expendiof Labour

into Conditions

9

Plantations in India", Government

ture', S G Sarkar, Commerce, July 12,

of India, Delhi, 1946, p 176.

1980, p 35.)

16 Jay R Mandle, 'The Plantation EcoHowever, the author's suggestion to

nomy: An Essay in Definition'

the role of subsidies refers

examine

36,

Volume

Society,

and

Scien7ce

10

Number 1, New York, 1972, p 57. to the Report on Controls and Sub11 Ibid.

1 ) Details of the wages in the Dooars

17 S W Mintz, 'Canamelar: The Sub- sidies of the Vadilal Dagli Committee

in the late nineteenth century are

cultuire of a Rural Sugar Plantation

which also highlighted the urgent need

not available. However, Sir PerciProletariat' in "The People of Puer- for examining subsidies whose desirval Griffiths, the Political Adviser

to Rico", Illinois, 1956, p 332.

ed effects depend on the elasticities

of the Indian Tea Association,

Guha, "From Planter

18 Amalendu

which was then (and still is) the

supply and demand for subsidised

of

Struggle

Raj to Swaraj: Freedom

niost -uowerful body of the planters,

as well as for income, and subgoods

Assam

Politics in

and Electoral

m1akes this statement in his book,

9-10.

pp

1977,

Delhi,

1826-1947",

effects of subsidies.

stitution

IndusTea

of

the

Indian

"Ihistory

19 Act XVII of 1859. This Act made

try", London, 1972, p 309-10.

Subsidies should be used as a temthe worker liable for prosecution if

13 W W Hunter, "Statistical Account

subhis porary economic tool. But the

he left the tea garden before

of Bengal: jalpaigtiri, Cooch Behar

of

Government

the

by

provided

sidies

contract period was over.

and Darjeeling Districts", Calcutta,

India, through the Central Budget,

20 Bege, ibid, p 96.

1872, p 278.

have become an enduring feature of

India's fiscal policy, as is rightly obby the author. A subsidy

served

implies a reallocation of resources

within the economy. In the short

A Comment

run, it is a burden to the tax-payer

and a relief to the producers. But in

Tapas K Chakrabarty

the longer run, its objective is to

accelerate growth for the benefit of

of the

(financial as wvell as non-financial) and the masses. Any suggestion in this

IN his article 'Expenditure

Central Government: Some Issues', July to the states should be carefully re- regard should be supported therefore

by the critical analysis of the subsi5, after presenting some theoretical as- assessed.

highlighted

Chona

really

deseive dies provided and their effects on the

Chona's endeavours

pects of fiscal policy

well the broad trends in the growth and high commendation. The study is well economy.

of the Governknit and highly thought provoking.

pattern of expenditure

It is interesting that a closer look

ment of India duiring the last three deHlowever, we feel that the shortcoming

the policies providing subsidies for

at

of the study is the purely macro apcades, with a view to suggesting some

fertilisers, export promotion, etc,

food,

where economies

proach in examining the scope of econoareas of expenditure

reveal the contradictory steps

will

effected

could be

mising on public expenditure, though

and rationalisation

the government with resthe

effect on

any adverse

the author has recognised the relevance adopted by

without

the

price stabilisation policy.

to

pect

of the micro approach in this regard

growth of the economy.

some evidence by studyget

may

One

has

finally that "the ap- (p 1147). The approach the author

Ile expresses

export promotion policy

recent

the

ing

proach of examining the scope for re- adopted in the study does not proceed

sector commodities

primary

some

on

on micro lines. The approach of the

duction in expendituire in various actirice bran,

de-oiled

fish,

as

rice,

such

vities of the Govemment of India has study is to our mind controvertible.

to

decision

The

government's

etc.

The question is, first, whether the

to be esse)7tiallyJ micro. Although in the

consuof

these

the

export

puiblic expenditure undergoing pheno- encourage

short rtn there may not be much flexiconsidered

succeeded in mer commodities is to be

menal growth has

expenditure, there

bility in the public

policy.

an

anti-inflationary

as

not

of

the

people

to

providing benefits

are nevertheless certain areas both with

about

question

the

raise

can

Anyone

the country, and second, whether it is

non-developmental

clevelopmental and

of

promotion

of

export

priority

the

following the ends it is designed to

expenditure where some economy in exprice

over

commodities

consumer

about" (p serve. One should attempt to get an

can be brought

penditure

policy when the economy

appropriate answer to this interlaced stabilisation

that there exists

1151). He advocates

inflation which is

a

two-digit

facing

is

issue on macro lines (adopted in his

some scope for economy in defence ex1980-81.

in

continue

to

likely

(peinditure reallocation of fund for re- study) as well as on micro lines (assessthat the perforis

aspect

collecAnother

not

a

policies,

ment of specific

search and development), administrative

mance of almost all public undertakexpenditure on social ser- tion of policies for specific purpose).

expenditure,

Apart

It is quite common that the mode ings in India is one of the most serious

vices (education and medical).

the

that

of

implementation of policies and the deficiencies on the economic scene.

also

suggests

he

these,

from

utilisation of funds affect the volume An estimate yields 23 instances of

role of suibsidies, particularly those on

examined

be

of

expenditure. In this context, we severe underutilisation of capacity

should

fertilisers,

food and

must try and understand that the role during 1977-78 (Commerce, July 12,

and that the transfer of funds to nonundertakings,

of government machinery is significant OP 38). This is not to deny that the

departmental commercial

6

Eric Wolf, 'Specific Aspects of the

New

in the

System

Plantation

World' in "Plantation Systems of the

New World", Washington, 1959, p

.36.

Myint, ibid, p 41.

Ibid, p 43.

Sanat Kumar Bose, "Capital and

Labour in the Indian Tea Industry",

Bose has

1954, p 7a.

Bombay,

quoted from a report of the SDO

of Karimganj, Assam.

Ibid, p 75.

14

Expenditure of the Central Government

1527

This content downloaded from 59.90.82.87 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 02:14:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Economics and Organization of Brazilian Agriculture: Recent Evolution and Productivity GainsFrom EverandThe Economics and Organization of Brazilian Agriculture: Recent Evolution and Productivity GainsNo ratings yet

- Social Character in a Mexican Village: A Sociopsychoanalytic StudyFrom EverandSocial Character in a Mexican Village: A Sociopsychoanalytic StudyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Farm Management - With Information on the Business, Marketing and Economics of Running a FarmFrom EverandFarm Management - With Information on the Business, Marketing and Economics of Running a FarmNo ratings yet

- The Travels of A T-Shirt in The Global Economy SCRDocument11 pagesThe Travels of A T-Shirt in The Global Economy SCRCarlos MendezNo ratings yet

- Effect of Neoliberal Policies On Tea Plantations - K.S ArshDocument3 pagesEffect of Neoliberal Policies On Tea Plantations - K.S ArshArsh K.SNo ratings yet

- Who Controls The Food System? by Judith HitchmanDocument15 pagesWho Controls The Food System? by Judith HitchmanKyle Sean YoungNo ratings yet

- Group Presentation On The Pastoral SpiralDocument6 pagesGroup Presentation On The Pastoral SpiralAMG 2001No ratings yet

- Farm Organization and Management - Land and Its Equipment - With Information on Costs, Stocking, Machinery and LabourFrom EverandFarm Organization and Management - Land and Its Equipment - With Information on Costs, Stocking, Machinery and LabourNo ratings yet

- Intravillage Wealth and Peasant Agricultural InnovationDocument15 pagesIntravillage Wealth and Peasant Agricultural InnovationAstrid Carolina Rozo CamposNo ratings yet

- Factsheet 9Document2 pagesFactsheet 9sarasijNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Labourers' Socio-Economic ConditionsDocument11 pagesAgricultural Labourers' Socio-Economic ConditionsKailash SahuNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument20 pagesResearch Papermohdarif.lawNo ratings yet

- Agricultural EconomicsDocument17 pagesAgricultural EconomicsNadeemAnwarNo ratings yet

- The Overview of Horticultural Growth The Role of Horticulture in Tamenglong District: A Survey Account of Ten Villages in The Tamenglong District, Manipur StateDocument9 pagesThe Overview of Horticultural Growth The Role of Horticulture in Tamenglong District: A Survey Account of Ten Villages in The Tamenglong District, Manipur Stateijsrp_orgNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Cooperatives and Farmers OrganizationsDocument7 pagesAgricultural Cooperatives and Farmers OrganizationsSamoon Khan AhmadzaiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press Comparative Studies in Society and HistoryDocument16 pagesCambridge University Press Comparative Studies in Society and HistoryAlexis Jaina TinaanNo ratings yet

- Comparing Haciendas and Plantations as Agricultural Systems in Latin AmericaDocument34 pagesComparing Haciendas and Plantations as Agricultural Systems in Latin AmericaMiguel MorillasNo ratings yet

- Who Will Tend The Farm? Interrogating The Ageing Asian FarmerDocument21 pagesWho Will Tend The Farm? Interrogating The Ageing Asian FarmerDena DrajatNo ratings yet

- Indian Agriculture Before ModernisationDocument32 pagesIndian Agriculture Before ModernisationArman DasNo ratings yet

- Download Contract Farming Capital And State Corporatisation Of Indian Agriculture 1St Edition Ritika Shrimali full chapterDocument67 pagesDownload Contract Farming Capital And State Corporatisation Of Indian Agriculture 1St Edition Ritika Shrimali full chapterkathryn.cooper259100% (2)

- OP 17 Logic of Farmer Enterprise Kanitkar PDFDocument19 pagesOP 17 Logic of Farmer Enterprise Kanitkar PDFShrinkhala JainNo ratings yet

- Agricultural ExtensionDocument281 pagesAgricultural ExtensionjimborenoNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of AgribusinessDocument5 pagesCharacteristics of AgribusinessMary Irish Cayanan JardelezaNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, LTD., ROAPE Publications LTD Review of African Political EconomyDocument15 pagesTaylor & Francis, LTD., ROAPE Publications LTD Review of African Political EconomyMauro FazziniNo ratings yet

- Zhang 2018Document204 pagesZhang 2018Marcelo Jara FalconiNo ratings yet

- Out-Grower Sugarcane Production Post Fast Track La PDFDocument33 pagesOut-Grower Sugarcane Production Post Fast Track La PDFMichael ZuluNo ratings yet

- Violations of Farm Workers' Labour Rights in Post-Apartheid South AfricaDocument24 pagesViolations of Farm Workers' Labour Rights in Post-Apartheid South AfricaPaloma Aguilar CuevasNo ratings yet

- Agri Chapter 1Document10 pagesAgri Chapter 1Fetsum LakewNo ratings yet

- Farming Systems Ch3Document9 pagesFarming Systems Ch3Redi SirbaroNo ratings yet

- Imhongirie Tessy Theresa: NameDocument11 pagesImhongirie Tessy Theresa: NameAdefisayo HaastrupNo ratings yet

- Re 03 Fa 01Document24 pagesRe 03 Fa 01Nilanka HarshaniNo ratings yet

- Who Are The Urban Farmers?Document22 pagesWho Are The Urban Farmers?MwagaVumbiNo ratings yet

- Agr Eco ProposalDocument16 pagesAgr Eco ProposalBarnababas BeyeneNo ratings yet

- Peasant MovementDocument22 pagesPeasant Movementrahul dadhichNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Agriculture Rural DevelopmentDocument9 pagesLiterature Review of Agriculture Rural DevelopmentbeqfkirifNo ratings yet

- Land Booklet SmallDocument28 pagesLand Booklet SmallDanielNo ratings yet

- Agriculture in India: Contemporary Challenges: in the Context of Doubling Farmer’s IncomeFrom EverandAgriculture in India: Contemporary Challenges: in the Context of Doubling Farmer’s IncomeNo ratings yet

- Good Crop / Bad Crop: Seed Politics and the Future of Food in CanadaFrom EverandGood Crop / Bad Crop: Seed Politics and the Future of Food in CanadaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Agrarian Structures: Feudal, Colonial & Capitalist ModesDocument11 pagesAgrarian Structures: Feudal, Colonial & Capitalist ModesTado LehnsherrNo ratings yet

- Project CHRANDocument63 pagesProject CHRANSatish VarmaNo ratings yet

- Farm Size and ProductivityDocument5 pagesFarm Size and ProductivityTanim BegNo ratings yet

- First Page. - SHAKTI (Sodeca)Document21 pagesFirst Page. - SHAKTI (Sodeca)LOMESH VERMANo ratings yet

- The Future of Small FarmsDocument54 pagesThe Future of Small FarmsfischertNo ratings yet

- Rural Wealth and Welfare: Economic Principles Illustrated and Applied in Farm LifeFrom EverandRural Wealth and Welfare: Economic Principles Illustrated and Applied in Farm LifeNo ratings yet

- Indian Manager StyleDocument7 pagesIndian Manager StyleNivedita KothiyalNo ratings yet

- 43 Mencher 2013Document38 pages43 Mencher 2013Aman KumarNo ratings yet

- Pluriactivity On Family FarmsDocument16 pagesPluriactivity On Family Farmskuba.jasinskiNo ratings yet

- Foundation Course in Science & Technology FST-1 (2019-20) : Last Date For Submission of AssignmentDocument13 pagesFoundation Course in Science & Technology FST-1 (2019-20) : Last Date For Submission of AssignmentAkshay jambhulkarNo ratings yet

- Green RevolutionDocument7 pagesGreen RevolutionShailjaNo ratings yet

- Rural Industry: InnovationsDocument11 pagesRural Industry: Innovationssiva nagendraNo ratings yet

- BCCA_6_ED_02_S1Document10 pagesBCCA_6_ED_02_S1Sheetal NafdeNo ratings yet

- Sugar HistoryDocument29 pagesSugar HistoryJesús Yair Ramirez VillalobosNo ratings yet

- The Case of Coffee Production in The Northern Mountain Region of VietnamDocument16 pagesThe Case of Coffee Production in The Northern Mountain Region of VietnamGustavo NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Agriculture and Allied Industries on Indian EconomyDocument26 pagesImpact of Agriculture and Allied Industries on Indian EconomyHariank GuptaNo ratings yet

- Fulltext PDFDocument12 pagesFulltext PDFMOEED MALIKNo ratings yet

- Labour welfare practices in Assam tea estateDocument9 pagesLabour welfare practices in Assam tea estatePaul ApurbaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 SummaryDocument6 pagesChapter 8 SummaryNAWAF ALSHAMSINo ratings yet

- Photojournalism - Nithin & RajeeshDocument11 pagesPhotojournalism - Nithin & RajeeshNithin KalorthNo ratings yet

- Field Hockey in IndiaDocument4 pagesField Hockey in IndiaNithin KalorthNo ratings yet

- The Future of Community Radio in India PDFDocument11 pagesThe Future of Community Radio in India PDFNithin KalorthNo ratings yet

- The Video Gamers Dileamma Entertainment Vs Morality - DR Sony & DR Kim, Nithin KalorthDocument12 pagesThe Video Gamers Dileamma Entertainment Vs Morality - DR Sony & DR Kim, Nithin KalorthNithin KalorthNo ratings yet

- Introduction To CinemaDocument123 pagesIntroduction To CinemaNithin Kalorth100% (1)

- Identification and Analysis of Images in AnjatheyDocument12 pagesIdentification and Analysis of Images in AnjatheyNithin KalorthNo ratings yet

- Kim Ki Duk Article On Mathrubhoomi WeeklyDocument9 pagesKim Ki Duk Article On Mathrubhoomi WeeklyNithin KalorthNo ratings yet

- Communication Research Methods I: ST Thomas Colege of Arts and Science ChennaiDocument3 pagesCommunication Research Methods I: ST Thomas Colege of Arts and Science ChennaiNithin KalorthNo ratings yet

- Practice Problems For Mid TermDocument6 pagesPractice Problems For Mid TermMohit ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Partner Ledger Report: User Date From Date ToDocument2 pagesPartner Ledger Report: User Date From Date ToNazar abbas Ghulam faridNo ratings yet

- Checklist ISO 20000-2018Document113 pagesChecklist ISO 20000-2018roswan83% (6)

- LU3 Regional PlanningDocument45 pagesLU3 Regional PlanningOlif MinNo ratings yet

- Book No. 13 Accountancy Financial Sybcom FinalDocument380 pagesBook No. 13 Accountancy Financial Sybcom FinalPratik DevarkarNo ratings yet

- 2021-09-21 Columbia City Council - Public Minutes-2238Document8 pages2021-09-21 Columbia City Council - Public Minutes-2238jazmine greeneNo ratings yet

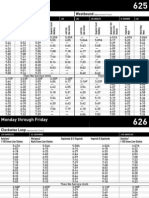

- LA Metro - 625-626Document4 pagesLA Metro - 625-626cartographicaNo ratings yet

- Licensed Contractor Report - June 2015 PDFDocument20 pagesLicensed Contractor Report - June 2015 PDFSmith GrameNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Globalization on Indian AgricultureDocument2 pagesImpacts of Globalization on Indian AgricultureSandeep T M SandyNo ratings yet

- Lumad Struggle for Land and Culture in the PhilippinesDocument10 pagesLumad Struggle for Land and Culture in the PhilippinesAlyssa Molina100% (1)

- Rapaport Diamond ReportDocument2 pagesRapaport Diamond ReportMorries100% (1)

- Lic Plans at A GlanceDocument3 pagesLic Plans at A GlanceTarun GoyalNo ratings yet

- JVA JuryDocument22 pagesJVA JuryYogesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Quiz 523Document17 pagesQuiz 523Haris NoonNo ratings yet

- The Role of Government in The Housing Market. The Eexperiences From AsiaDocument109 pagesThe Role of Government in The Housing Market. The Eexperiences From AsiaPUSTAKA Virtual Tata Ruang dan Pertanahan (Pusvir TRP)No ratings yet

- Industrial Visit ReportDocument6 pagesIndustrial Visit ReportgaureshraoNo ratings yet

- The Cold War - David G. Williamson - Hodder 2013 PDFDocument329 pagesThe Cold War - David G. Williamson - Hodder 2013 PDFMohammed Yousuf0% (1)

- Form 16 TDS CertificateDocument2 pagesForm 16 TDS CertificateMANJUNATH GOWDANo ratings yet

- Final EA SusWatch Ebulletin February 2019Document3 pagesFinal EA SusWatch Ebulletin February 2019Kimbowa RichardNo ratings yet

- Cover NoteDocument1 pageCover NoteSheera IsmawiNo ratings yet

- Macro and Micro AnalysisDocument20 pagesMacro and Micro AnalysisRiya Pandey100% (1)

- Manual Book Vibro Ca 25Document6 pagesManual Book Vibro Ca 25Muhammad feri HamdaniNo ratings yet

- Advt Tech 09Document316 pagesAdvt Tech 09SHUVO MONDALNo ratings yet

- Hotel Industry - Portfolia AnalysisDocument26 pagesHotel Industry - Portfolia Analysisroguemba87% (15)

- Palo Leyte Palo Leyte: Table 1Document5 pagesPalo Leyte Palo Leyte: Table 1samson benielNo ratings yet

- Mahanagar CO OP BANKDocument28 pagesMahanagar CO OP BANKKaran PanchalNo ratings yet

- Understanding SpreadsDocument42 pagesUnderstanding Spreadsluisfrod100% (8)

- COA - M2017-014 Cost of Audit Services Rendered To Water DistrictsDocument5 pagesCOA - M2017-014 Cost of Audit Services Rendered To Water DistrictsJuan Luis Lusong67% (3)

- Request Travel Approval Email TemplateDocument1 pageRequest Travel Approval Email TemplateM AsaduzzamanNo ratings yet

- Tax Invoice: Tommy Hilfiger Slim Men Blue JeansDocument1 pageTax Invoice: Tommy Hilfiger Slim Men Blue JeansSusil Kumar MisraNo ratings yet