Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Inherence of Caste An Anthropological Study On Nais

Uploaded by

The Explorer IslamabadOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Inherence of Caste An Anthropological Study On Nais

Uploaded by

The Explorer IslamabadCopyright:

Available Formats

The Explorer Islamabad: Journal of Social Sciences

ISSN (E): 2411-0132, ISSN (P): 2411-5487

Vol-1, Issue (5):141-144

www.theexplorerpak.org

INHERENCE OF CASTE: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY ON NAIS

Saba Yasmeen1, Usman Akram2

Department of Anthropology, PMAS-Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi, 2 Department of Information

Technology, Preston University, Islamabad

Corresponding Author:

Saba Yasmeen

PMAS-Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi

Sabayasmeen915@gmail.com

Abstract:Caste plays an imperative role in this part of the world- the south Asia. People cannot change their occupational

castes on their will, and the status remains attached to them for many generations to come. The research was an attempt

to study the traditional Nais .This occupational group is extremely hardworking and provides multifaceted services to the

community, ranging from cooking and dish washing to circumcision and minor surgeries. The data was collected using

snowball sampling technique, while the sampling frame included exclusively Nais and their families. The study was

conducted over a period of one month. The data was then analyzed through percentile analysis. The locale of the study was

under union council Dhudial district Chakwal. A sample of 60 respondents was gathered from the locale where each

sampling unit stands for a single Nai household. Though they are a part of a discriminated caste, are still proud of their

professional services which they offering to their community. The data reveals a mere tinge of caste mobility among a few

families who were motivated by status mobility to which an occupation is a major hindrance.

Key Words: Caste, Kammi, Nais, Occupational caste, Cooking, Dish Washing

INTRODUCTION

The word barber is derived from a Latin word

barbawhich means Beard. A barber is a person

whose job is to cut, dress, shave do styling of men

hair. In past, barbers started with hair dressing but,

their low income forced them to adopt some other

allied roles which could help them earn a better

livelihood. The entire hair dressers were refereed as

barbers. In present era the word barber is used for

hair dresser who cuts mens hair as well as a

professional title. Their income is very low which

cannot fulfill their basic needs. For this reasons some

of them opted for other professions like brick making.

They also perform various other tasks like dish

washing, cooking meals on special occasions like

wedding ceremonies, death ceremonies and also

performed birth rituals such as shaving of a new born

a head and circumcision of male kids. It has also seen

observed that barbers traditionally Nais played a

significant role by being a messenger on wedding

ceremonies of the local population. They also did

minor surgeries required for the treatment of skin

related issues.

Since occupational castes play an important role in

this part in the world, the concept of closed caste

system has been diffused into our culture too. It was

borrowed from the phenomenon of Hindu jati system

which was prevalent in this part of the world for

centuries. Though, the effects of diffusion should

have worn off after the partition, yet we see a deep

rooted influence of caste system in our society. No

one can change his/her caste with his own will. The

term caste is derived from the Latin word castus

which means clean. The word castus became the

root word of the French word casta meaning breed,

race or a complex of traditional qualities

(Parinthirickal 2006). Caste is often termed as a class.

In Hindu caste system there are four prevailing

classes i.e. Brahmins, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra,

similar to this concept there are caste variances in

villages of Punjab too. The two classes zamindars and

Kammisthat are classified as high class and low class

(Ahmad 1970; Eglar 1960). Zamindars are those

members of the community that own lands passed

down from their forefather and are involved in

farming. They are landlords of their native village and

enjoy this status along with various benefits like

services from the working class. In return of these

services the working class or Kammisare provided

with raw food, grain i.e. Annaj. The working class

141

includes Nais, Mochi, Kumar, Julaha, Musalli and

Lohaars. They are collectively known as Kammis.

Different landowning quomstraditionally associated

with cultivation as their parentage occupation are

called

zamindars.

Members

of

a

zamindarquomresiding in a village own land with

varying size of their landholdings. On the other hand,

different artisan and service providing quomse.g.

barber, carpenter, cobbler, blacksmith, weaver,

potter, Musalli(labourer) are jointly called as kammi

(Ahmad 1970; Alavi 1972; Eglar 1960).

Traditionally, kammi-zamindar has been used as by

lateral relationship, indigenously known as Seyp.

Nais, have usually inherited these skills from their

forefathers. They keep on struggling, laboring,

provide services only to please their landowner and

gain favors in return. The conservative work about

linking property-owners and the service class is

familiar like as Seyp organization that includes

kammis, who struggle as labor for the landowners.

They work throughout the village by offering their

heritage skills as services to the villagers. The labor

involved in seyp, not only works in the fields of the

zamindarfamily but also serves as his household

labor. However, the caste system in rural Punjab has

changed over time and its characteristic need revision

e.g. labour relations (Chaudhary 1999; Lyon 2004).

However, the caste system in rural Punjab has

changed over time and its characteristic need revision

e.g. labour relations (Chaudhary 1999; Lyon 2004).

Kammiearn their source of income for the most part

throughout these caste based profession (Eglar

1960). When they are unable to make a good living

out of their traditional occupation, they prefer

occupational shift. The study revised that major

reason behind their abstinences from status shifting

is their lack of education. When engaged in the

manufacturing and production professions, they are

faced with issues related to lack of vocational

training. Thus there is a trend in the service class to

move around the cities and serve as foreign labor in

Middle Eastern countries. Furthermore there is a

rising tendency among kammis to migrate to cities or

abroad to earn a living. Different studies have

explored that the caste based occupations of

kammiare in decline because of the availability of

alternative employment opportunities e.g. industrial

and government jobs. Moreover, there are increasing

trends among kammito migrate towards cities and

foreign countries for earning purposes. As a result,

the traditional labour relations between kammiand

zamindarshave been transformed and are coming to

an end with the passage of time (Chaudhary 1999;

Hooper and Hamid 2003).

No doubt money whitens everything, but people are

known by their ancestry especially in the area to

which they belong to. The traditional labour relation

between zamindarsand kammiis known as Seyp

system in which kammiused to work as labor for

zamindarsbesides serving the villagers with their

parentage crafts. Kammiearned their livelihood

predominantly through their caste based occupations

(Eglar 1960). However, it is important to note that

though kammiin contemporary rural Punjab are

increasingly opting for other professions, they are

always identified in the village setting through their

parentage occupations e.g. barber, carpenter etc.

(Lyon 2004).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted in district Chakwal with

particular focus on the significance of traditional nais

in rural areas. The data was gathered from a sample

of 60 respondents both males and females. The

sampling units included Nais and their families

selected through snowball sampling. The study was

conducted in a period of one month with the help of

semi structured questionnaire.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

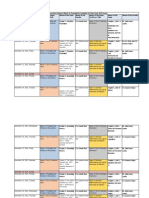

Table: Percentile results regarding Social Life of Nais

QUESTIONS

Responses

Percentage

Nais work for zamindars

Yes

No

Yes

No

90

10

90

10

Yes

No

Yes

No

0

100

10

90

Yes

No

94

6

Nais wish to change their

status

Nais change their caste

Nais having their own

land

Nais perform endogamy

According to percentile analysis 90 % of the

respondents agreed that nais have been working for

zamindars for centuries. Those people who have

changed their profession, education, gone abroad

and doing a better earning have started purchasing

agricultural land even they were known by the same

caste in the village. A few kammiin a Punjabi village

may own some land and thus cultivate. Nevertheless,

they are not given the status of being zamindarssince

142

this status is associated with the quommembership

and not the material possessions (Eglar 1960; Lyon

2004).

90 % of the respondents said that they wanted to

change their status to gain a better position in the

society but no matter how hard they tried the caste

and its status remains attached with them as long as

they remain in their native area. According to some

permanent settlers, some people have changed their

status and profession by migrating from one place to

another.

According to percentile analysis 0% respondents said

that they change their castes. They believed that

since they all were Nais, and the stigma attached is

unchangeable they felt proud of their caste and

profession Caste expressed as a patrilineage

whereby all men can trace their relationship to a

common ancestor, no matter how remote, they may

belong to the same biradari (Eglar 1960). However,

the key informant and the old settlers informed that

all those who had migrated from the area changed

their castes.

Only 10 % respondents had their own land while 90

%Nais were those who worked as tenants or kammis

for zamindars for the fulfillment of their subsistence

needs. The Nais having their own land belonged to

the category who had an opportunity to gain

education and search for better employment.

94 % respondents revealed that they strictly follow

the tradition of endogamous marriage i.e. within

their own qoum. A minor proportion of 6 % were also

practicing exogamy. Marrying within ones own

occupational quomis not an absolute rule of

endogamy among Kammiand they may marry within

other Kammiquomse.g. barbers within cobblers. On

the contrary, all of the Kammirespondents in the

present research stressed that they marry only in

their occupational quomsby parentage e.g. barbers

within barbers, or carpenters within carpenters

(Lyon 2004).

Majority of the respondents suggested that they wish

to marry within their own group as well as those who

are compatible with their social status, though caste

was seen as the primary factor determining ones

social status in the village life. Lifelong stigma of

being Kammi always keeps Kammi inferior in terms

of identity and status in the village setting. The

impact of learning lying on structure of the

community morals could be distorted some place

conventionally community structure survive at the

side of a contemporary financial system including

unbending variety of the epoch and the sexual

characteristic stratification were maintain (Loscocco

and Kalleberg 1988). Nevertheless, the villagers may

give consideration to the possession of financial

assets of other family, and educational/professional

activities of the men/women in the process of

partner selection. Similarly, zamindar respondents

highlighted the parentage occupational identity of

Kammi and thus their lower standing on the status

hierarchy as the major reason of caste based

endogamy between Kammiand zamindars.

CONCLUSION

Lack of resources is considered as an impediment in

growth of individuals. Education is considered as the

most empowering and enlightening element that can

groom and develop us to transform in a better

society. Yet, in the 21st century there still exist

societies where caste system is innately embedded in

the social fabric to an extent that it restrains the

growth of individual by undermining their abilities on

the basis of their ancestral linkages.

REFERENCES

Alavi, Hamza

1972 Kinship in West Punjabi Villages.

Contributions to Indian Sociology 6(1):1-27.

Ahmad, Saghir

1970 Social Stratification in a Punjabi

Village. Contributions to IndianSociology 4(1):

105-125.

Chaudhary,Muhammad Azam

1999 Justice in Practice: legal Ethnography

of a Pakistani Punjabi Village: Oxford

University Press, USA.

Eglar, ZekiyeSuleyman

1960 A Punjabi Village

Columbia University Press.

in

Pakistan:

Hooper, Emma, and Agha Imran Hamid

2003 Scoping Study on Social Exclusion

in Pakistan. Islamabad: DFID.

Loscocco, Karyn A. and Arne L. Kalleberg

1988 Age and the meaning of work in the

United States and Japan. Social Forces

67(2):337-356.

Lyon, Stephen M.

2004 An anthropological Analysis of local

143

Politics and Patronage in a Pakistani village.

Edwin Mellen Press.

Nadvi, Khalid, and Mark Robinson

2004 Pakistan drivers of change. Sussex,

UK: Institute of Development Studies.

Parinthirickal, Mathew.

2006 Caste

System. Vijnanadipti: A Journal of

Philosophico-TheologicalReflection. 8(2):156.

2015The Explorer Islamabad Journal of Social Sciences-Pakistan

144

You might also like

- Achievement Motivation and Career Decision Making Among YouthDocument3 pagesAchievement Motivation and Career Decision Making Among YouthThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Co-Curricular Activities A Study at Pmas Arid Agriculture University, RawalpindiDocument6 pagesBenefits of Co-Curricular Activities A Study at Pmas Arid Agriculture University, RawalpindiThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Purification of Soul in Kalash Community Before and After DeathDocument3 pagesPurification of Soul in Kalash Community Before and After DeathThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Women Empowerment Endorsement of Right To Career Development Among Tribal Masid WomenDocument6 pagesWomen Empowerment Endorsement of Right To Career Development Among Tribal Masid WomenThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- English Real Exploring The Changing Trends in GreetingsDocument3 pagesEnglish Real Exploring The Changing Trends in GreetingsThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Explore Causes and Effect of Age Bound Diseases On Life of Aged PeopleDocument5 pagesExplore Causes and Effect of Age Bound Diseases On Life of Aged PeopleThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Causes and Consequences of MalnutritionDocument4 pagesCauses and Consequences of MalnutritionThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Breast Fibro Adenomas in Female An Anthropo-Medical ApproachDocument4 pagesBreast Fibro Adenomas in Female An Anthropo-Medical ApproachThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Social Neglect and Ageing Population A Pilot Study On Violence Against Senior CitizensDocument6 pagesSocial Neglect and Ageing Population A Pilot Study On Violence Against Senior CitizensThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Population Growth and Increase in Domestic Electricity Consumption in PakistanDocument7 pagesPopulation Growth and Increase in Domestic Electricity Consumption in PakistanThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Its Impact On The Third WorldDocument5 pagesGlobalization and Its Impact On The Third WorldThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Social Interaction at House Hold Level and Mental HealthDocument3 pagesSocial Interaction at House Hold Level and Mental HealthThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Let Shepherding EndureDocument4 pagesLet Shepherding EndureThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Familial Care and Social Protection As Combined Phenomenon Towards Productive AgingDocument5 pagesFamilial Care and Social Protection As Combined Phenomenon Towards Productive AgingThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Change in Income and Architectural TransformationDocument3 pagesChange in Income and Architectural TransformationThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Socioeconomic Causes of Devaluation of Pashtun ValuesDocument7 pagesSocioeconomic Causes of Devaluation of Pashtun ValuesThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Telecommunication On The Household Economy After EarthquakeDocument3 pagesThe Impact of Telecommunication On The Household Economy After EarthquakeThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Livelihood of People in District JhelumDocument8 pagesLivelihood of People in District JhelumThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Anthropology and Ageing Population An Anthropo-Psychological Analysis of Seniors Citizens of RawalpindiDocument6 pagesAnthropology and Ageing Population An Anthropo-Psychological Analysis of Seniors Citizens of RawalpindiThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Ethnographical Study of Postpartum Practices and Rituals in Altit HunzaDocument6 pagesEthnographical Study of Postpartum Practices and Rituals in Altit HunzaThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Voting Behavior and Election in PakistanDocument8 pagesVoting Behavior and Election in PakistanThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Technology On Social Transformation in Agrarian CommunityDocument4 pagesThe Impact of Technology On Social Transformation in Agrarian CommunityThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Mobile Phones Addiction Among University Students Evidence From Twin Cities of PakistanDocument5 pagesMobile Phones Addiction Among University Students Evidence From Twin Cities of PakistanThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- A Sociological Analysis of Female Awareness and Violation of Rights in Southern Punjab A Case Study in District MuzaffargarhDocument3 pagesA Sociological Analysis of Female Awareness and Violation of Rights in Southern Punjab A Case Study in District MuzaffargarhThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Male Out Migration and The Changing Role of Women in Saidu Sharif District Swat, KPK PakistanDocument3 pagesMale Out Migration and The Changing Role of Women in Saidu Sharif District Swat, KPK PakistanThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Dating Culture in Pakistani Society and Its Adverse Effects Upon The Adolescents, in The Perspective of Prevalent Technology and InnovationsDocument11 pagesDating Culture in Pakistani Society and Its Adverse Effects Upon The Adolescents, in The Perspective of Prevalent Technology and InnovationsThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Mass Media Influence in Our Society An Evaluation at Jhehlum CityDocument4 pagesMass Media Influence in Our Society An Evaluation at Jhehlum CityThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Ejss 82 Impact of Modernization and Changing Traditional Values of Rural Setup in District Khushab - 2 PDFDocument4 pagesEjss 82 Impact of Modernization and Changing Traditional Values of Rural Setup in District Khushab - 2 PDFThe Explorer IslamabadNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- A. Rationale: Paulin Tomasuow, Cross Cultural Understanding, (Jakarta: Karunika, 1986), First Edition, p.1Document12 pagesA. Rationale: Paulin Tomasuow, Cross Cultural Understanding, (Jakarta: Karunika, 1986), First Edition, p.1Nur HaeniNo ratings yet

- The Leaders of The NationDocument3 pagesThe Leaders of The NationMark Dave RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-The Indian Contract Act, 1872, Unit 1-Nature of ContractsDocument10 pagesChapter 1-The Indian Contract Act, 1872, Unit 1-Nature of ContractsALANKRIT TRIPATHINo ratings yet

- NotesTransl 108 (1985) Larsen, Who Is This GenerationDocument20 pagesNotesTransl 108 (1985) Larsen, Who Is This GenerationluzuNo ratings yet

- Space 1999 Annual 1979Document62 pagesSpace 1999 Annual 1979Brin Bly100% (1)

- VIACRYL VSC 6250w/65MP: Technical DatasheetDocument2 pagesVIACRYL VSC 6250w/65MP: Technical DatasheetPratik MehtaNo ratings yet

- Mafia Bride by CD Reiss (Reiss, CD)Document200 pagesMafia Bride by CD Reiss (Reiss, CD)Aurniaa InaraaNo ratings yet

- Purnanandalahari p3D4Document60 pagesPurnanandalahari p3D4anilkumar100% (1)

- Materials Science & Engineering A: Alena Kreitcberg, Vladimir Brailovski, Sylvain TurenneDocument10 pagesMaterials Science & Engineering A: Alena Kreitcberg, Vladimir Brailovski, Sylvain TurenneVikrant Saumitra mm20d401No ratings yet

- The Seven Seals of Revelation and The SevenDocument14 pagesThe Seven Seals of Revelation and The Sevenyulamula100% (2)

- Understanding Urbanization & Urban Community DevelopmentDocument44 pagesUnderstanding Urbanization & Urban Community DevelopmentS.Rengasamy89% (28)

- American Literature TimelineDocument2 pagesAmerican Literature TimelineJoanna Dandasan100% (1)

- IELTS Writing Task 2/ IELTS EssayDocument2 pagesIELTS Writing Task 2/ IELTS EssayOlya HerasiyNo ratings yet

- Analog Communication Interview Questions and AnswersDocument34 pagesAnalog Communication Interview Questions and AnswerssarveshNo ratings yet

- Yayasan Pendidikan Ramadanthy Milad Anniversary SpeechDocument6 pagesYayasan Pendidikan Ramadanthy Milad Anniversary SpeechDina Meyraniza SariNo ratings yet

- Psyclone: Rigging & Tuning GuideDocument2 pagesPsyclone: Rigging & Tuning GuidelmagasNo ratings yet

- Flow Through Pipes: Departmentofcivilengineering Presidency University, Bangalore-64 BY Santhosh M B Asstistant ProfessorDocument15 pagesFlow Through Pipes: Departmentofcivilengineering Presidency University, Bangalore-64 BY Santhosh M B Asstistant ProfessorSanthoshMBSanthuNo ratings yet

- New Wordpad DocumentDocument6 pagesNew Wordpad DocumentJonelle D'melloNo ratings yet

- X32 Digital Mixer: Quick Start GuideDocument28 pagesX32 Digital Mixer: Quick Start GuideJordán AstudilloNo ratings yet

- Din en 912-2001Document37 pagesDin en 912-2001Armenak BaghdasaryanNo ratings yet

- Xbox Accessories en ZH Ja Ko - CN Si TW HK JP KoDocument64 pagesXbox Accessories en ZH Ja Ko - CN Si TW HK JP KoM RyuNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Fuel Cell Testing Protocols PDFDocument7 pagesA Comparison of Fuel Cell Testing Protocols PDFDimitrios TsiplakidesNo ratings yet

- 4PW16741-1 B EKBT - Bufftertank - Installation Manuals - EnglishDocument6 pages4PW16741-1 B EKBT - Bufftertank - Installation Manuals - EnglishBernard GaterNo ratings yet

- Chich The ChickenDocument23 pagesChich The ChickenSil100% (4)

- Strategicmanagement Finalpaper 2ndtrisem 1819Document25 pagesStrategicmanagement Finalpaper 2ndtrisem 1819Alyanna Parafina Uy100% (1)

- Aemses Sof Be LCP 2021 2022Document16 pagesAemses Sof Be LCP 2021 2022ROMEO SANTILLANNo ratings yet

- 1ST Periodical Test ReviewDocument16 pages1ST Periodical Test Reviewkaren rose maximoNo ratings yet

- The Issue of Body ShamingDocument4 pagesThe Issue of Body ShamingErleenNo ratings yet

- Henderson PresentationDocument17 pagesHenderson Presentationapi-577539297No ratings yet

- PPPoE Packet Format - HCNADocument6 pagesPPPoE Packet Format - HCNARobert Sanchez OchochoqueNo ratings yet