Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Guidelines For The Management of Epilepsy in The Elderly Acta Neurol Belg 2006

Uploaded by

jessicaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Guidelines For The Management of Epilepsy in The Elderly Acta Neurol Belg 2006

Uploaded by

jessicaCopyright:

Available Formats

Acta neurol. belg.

, 2006, 106, 111-116

Guidelines

Guidelines for the management of epilepsy in the elderly

M. OSSEMANN, E. BRULS, V. DE BORCHGRAVE, C. DE COCK, C. DELCOURT, V. DELVAUX, C. DEPONDT, M. DE TOURCHANINOFF,

T. GRISAR, B. LEGROS, F. LINARD, I. LIEVENS, B. SADZOT and K. VAN RIJCKEVORSEL

Groupe de travail des Centres francophones de rfrence de lpilepsie rfractaire

Abstract

Diagnosis

Seizures starting in patients over 60 years old are frequent. Diagnosis is sometimes difficult and frequently

under- or overrated. Cerebrovascular disorders are the

main cause of a first seizure. Because of more frequent

comorbidities, physiologic changes, and a higher sensitivity to drugs, treatment has some specificity in elderly

people.

The aim of this paper is to present the result of a consensus meeting held in October 2004 by a Belgian

French-speaking group of epileptologists and to propose

guidelines for the management and the treatment of

epilepsy in elderly people.

Key words : Epilepsy ; elderly ; management.

Introduction

In industrialized countries, the population is ageing and therefore, the number of old patients with

brain insults is increasing. Among these, seizures

become a frequent and expensive medical problem.

Due to physiologic changes of metabolism and

higher frequency of comorbidities, diagnosis and

treatment of epilepsy in elderly people need specific considerations.

This paper presents a consensus of the Belgian

French-speaking group of the reference centres for

refractory epilepsy on the management and the

therapeutic attitude on epilepsy in elderly people.

Epidemiology

Elderly people have the highest incidence of

new-onset seizures (Hauser et al. 1993). Twentyfour percent of new onset seizures happen after the

age of 60 years old (Sander et al. 1990). This incidence seems to be due to the increasing lifespan

and the increasing abilities of physicians to diagnose seizure in old people. Recent studies seems to

show that the recurrence rate after a new-onset

seizure in the elderly could be greater than 90% if

untreated (Ramsay et al. 2004).

The diagnosis of seizures is more difficult to

establish because of the high incidence of codiseases and great imitators of epilepsy in old

age. These great imitators are the main cause of

over diagnosis of epilepsy ; they are mainly syncope, episodic vertigo, hypoglycaemia, metabolic

disorders, transient ischemic attacks, non-specific

episodes of dizziness, confusional states, transient

global amnesia or psychiatric illness.

On the other hand, focal seizures may remain

ignored and be a cause of underdiagnosis of epilepsy. Symptoms as confusional states, hallucinations

or automatisms are misleading and frequently considered as manifestations of neurodegenerative or

psychiatric disorders. This is particularly emphasised by the predominance of focal seizures (52%)

after 60 years in the Rochester epidemiological

study (Hauser et al. 1993).

As with younger patients, EEG plays an important role, but is too often overestimated in elderly :

normal variant patterns considered as epileptiform

abnormalities, or non-specific abnormalities are

more frequently recorded in older age (Drury and

Beydoun 1993). Furthermore, variations of vigilance during EEG recording are more frequent and

increase the complexity of the interpretation

(Santamaria and Chiappa 1987). On the other hand,

interictal epileptiform activities were recorded less

often (26-37%) compared to younger patients

(Dam et al. 1985, Henny et al. 1990, Drury and

Beydoun 1998).

Therefore, this larger range of non specific data

in older people decreases EEG sensitivity in this

population. Consequently, prolonged EEG with

sleep (night or nap) is often useful. We propose to

do a sleep or a nap EEG recording if the awake

EEG is negative.

Another specific indication for EEG recording in

elderly patients, even in emergency conditions, is

the suspicion of non convulsive status epilepticus

when the patient is confused without known

aetiology as metabolic disorder.

112

M. OSSEMANN ET AL.

Aetiology

Treatment

In elderly people, symptomatic focal epilepsies

are the most represented and a presumed aetiology

can be identified at least 70% of the cases. The most

frequent causes of epilepsies in elderly people are

cerebrovascular diseases (40.7%) and degenerative

disorders (16.5%). Tumours (5.5%), traumatism

(2.2%), metabolic complications, drug-induced

seizures and infection are quite rare (Hauser et al.

1993). Moreover very rare cases of idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) occurring after 60 years of

age were reported (Loiseau et al. 1998, Hiyoshi and

Yagi 2000). Gastaut considered that an onset of primary IGE is quite unusual in the elderly people and

that earlier seizures are frequently found (Gastaut

1981). He also showed that most cases of late onset

primary IGE occur in 40 to 50-year-old-women,

stressing the role of menopause and sexual hormones on convulsive threshold (Gastaut 1982).

Others have shown an increasing rate of seizure

between 40 and 60 years of age.

Cerebrovascular disorders are the most common

pathological factor underlying seizure(s) in elderly

people (Sung and Chu 1989, Loiseau et al. 1990,

Hauser et al. 1993) and the first cause of status

epilepticus in this population (Sung and Chu 1989).

Poststroke seizures are usually occur in a bimodal

distribution : early onset (during the first two

weeks after the stroke) and late onset seizures

(Louis and McDowell 1967, Kilpatrick et al. 1992,

Berges et al. 2000). The remote seizure rate in the

acute poststroke period reaches 6% (Reith et al.

1997, Arboix et al. 1997) with a recurrence rate of

3-5.7% during the first year after the stroke and

between 7.4-11.5% at five years (So et al. 1996,

Burn et al. 1997). The cumulative incidence of late

onset seizure was evaluated to 19% at 6 years (So

et al. 1996). Retrospective studies have shown that

the recurrence rate of late-onset seizures was

around 35% (Gupta et al. 1988, Milandre et al.

1992, Kilpatrick et al. 1992). Some neuroimaging

features seem to indicate risk of relapsing seizures.

These features are : cortical involvement, large

infarction, involvement of temporo-parietal cortex

and hemorrhagic strokes (review in Ossemann

2002).

A recent study showed that the occurrence of

one late-onset seizure significantly increases the

risk of having a subsequent stroke. Thus, if no

cause is found after a first seizure in a old patients,

it is suggested that screening and treatment for vascular risk factor should be done (Cleary et al.

2004).

In a group of 81 patients with neuropathological

signs of Alzheimers disease, 10% had seizures and

10% had myoclonus (Hauser et al. 1986). A diagnosis of Alzheimers disease or other dementia is

associated with at least a six-fold increased risk of

unprovoked seizure (Hesdorffer et al. 1996).

GUIDELINES FOR TREATMENT

When a seizure has been proved of epileptic origin, the first question is whether the seizure was

provoked, therefore considered as an acute symptomatic seizure. Usually these symptomatic seizures

do not require any chronic antiepileptic drug therapy.

If the first seizure appears unprovoked, the second question is : what is the risk of relapse and

should this seizure be treated ?.

There is no clear answer in the literature. In a

prospective epidemiological study, seizure recurrence rates were 14, 29 and 34% at 1, 3 and 5 years

after the first seizure. But in symptomatic seizure,

depending on clinical features, this risk is increased

to 20 to 80% at 5 years (Hauser et al. 1990). A

remote cerebral lesion and epileptiform discharges

on EEG are clear risk factors of recurrence after a

first seizure (Rocca et al. 1987, Hauser et al. 1990,

van Donselaar et al. 1991, FIRST Group 1993).

Different studies have shown that seizure recurrence is more frequent in elderly patients (FIRST

Group 1993, Ramsay et al. 2004).

Unfortunately, there is no agreement about the

recurrence of seizure after treatment. A study has

not shown any difference in the relapse rate with or

without treatment (Hauser et al. 1990), even when

in FIRST study treated patients have a lower recurrence rate of seizure (FIRST Group 1993).

Due to the high recurrence rate, we propose to

treat after a first unprovoked seizure in the presence

of a brain lesion or epileptiform abnormalities. For

a first unprovoked seizure of unknown origin, the

decision to treat should be individualised, after the

evaluation of the vital risk induced by cormorbidities, the increased risk of status epilepticus in elderly population, the risk of serious injuries especially

bone fracture in osteoporotic patients, and the

potential adverse events of antiepileptic drugs

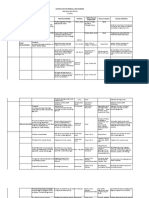

(Fig. 1).

CHOICE OF TREATMENT

Guidelines for the choice of treatment in elderly

persons with epilepsy are the same as for the whole

epileptic population in general (de Borchgrave et

al. 2002). However, specific consideration must be

taken into account because elderly people present a

hypersensitivity to antiepileptic drug (AED)

(Table 1). The ideal drug in elderly patient does not

exist. Ideally, this drug should be effective, well

tolerated, with a simple metabolism and without

significant drug interaction. The choice of an AED

is difficult because there are few evidence based

data on the use of these drugs in elderly patients,

especially in the very old and in elderly with codisease(s).

113

EPILEPSY IN THE ELDERLY

FIG. 1. Algorithm for decision to treat after a first seizure

Table 1

Responsible factors of hypersensitivity to AED in elderly patients

Pharmacodynamic

hypersensitivity

Glomerular

filtration rate

Metabolic

clearance

Serum albumin body fat/lean

(increase of

mass ratio

free fraction)

( volume of

distribution)

CBZ

LTG, OXC, PB, PHT,

TGB, TPM, VPA

GBP

LEV

LTG

( CBZ)

OXC

CBZ, ( PB), PHT

PB

LTG, CBZ, OXC, PHT,

TGB, TPM, VPA

PHT

LTG, CBZ, OXC, PB,

TGB, TPM, VPA

PGB

TGB

TPM

( PHT)

VPA

LTG, PB,

( CBZ, PHT)

VGB

AEDs interaction

CBZ : carbamazepine ; GBP : gabapentin ; LTG : lamotrigine ; OXC : oxcarbazepine ; PB : phenobarbital ; PHT : phenytoin ;

PGB : pregabalin ; TGB : tiagabine ; TPM : topiramate, VPA : valproate ; VGB : vigabatrin.

114

M. OSSEMANN ET AL.

Because pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic sensitivity in elderly patients is highly variable,

there are no specific doses for these patients. Thus,

the dosage must be adapted individually. The first

general rule is start low and go slow ; the second

one is monotherapy, as long as possible. Despite

these principles, active searching of potential side

effects is necessary.

Old AEDs have complex pharmacokinetic

(phenytoin), important cognitive side effects (phenobarbitone), osteoporotic effects (phenobarbitone,

phenytoin) (Christiansen et al. 1973), or important

hepatic induction (carbamazepine, phenobarbitone,

phenytoin). They should be avoided as much as

possible in elderly patients. If treatment with

phenytoin or phenobarbitone is mandatory, active

search of osteoporosis by osteodensitometry

should be done and in osteopenic patients treatment

with calcium supplementation and vitamin D

should be introduced, according to our previous

guidelines on this subject (Legros et al. 2003).

In first line treatment and due to the adverse

events of previously described old AEDs we recommend the use of valproate if a rapid titration or

an intravenous use is necessary. This choice is justified because the Cochrane Review does not find

any evidence of a significant difference exists

between phenytoin and valproate for the outcome

(Tudur et al. 2001). When urgent use of an AED is

not mandatory, new AEDs may be proposed in

accordance to the US guidelines on the use of new

AEDs in new onset epilepsy (French et al. 2004)

and the Belgian reimboursing rules. In a doubleblind, multicenter study in elderly patients, the efficacy of lamotrigine has been shown equal to carbamazepine, but due to adverse events the rate of

withdrawal is significantly higher with carbamazepine (Brodie et al. 1999). These results were

recently confirmed by the US veteran study

(Rowan et al. 2005). Topiramate is another first line

alternative treatment. The result of a recent topiramate monotherapy prospective study had shown a

high retention rate and a good tolerance to the drug

in an elderly patients subgroup (Groselj et al.

2005). There is also some evidence for the usefulness of gabapentin and levetiracetam in elderly

people, but the Belgian reimbursement rules limited there use in add-on therapy. Concerning

gabapentin, a double-blind study shows a better tolerance than carbamazepine in old patients

(Chadwick et al. 1998). These results were confirmed in the US veteran study (Rowan et al. 2005).

Moreover in term of efficacy, no difference, was

noted between gabapentin, carbamazepine and

lamotrigine. Recent data concerning the use of levetiracetam in old patients revealed a favourable

profile of tolerance (Cramer et al. 2003). The good

efficacy of levetiracetam was shown in a subset

analysis of the open-label add-on therapy KEEPER

trial (Ferrendelli et al. 2003) and in a small first

line therapy in elderly patients (Alsaadi et al. 2004)

(Fig. 2).

GBP : gabapentin ; LTG : lamotrigine ; LEV : levetiracetam ; TPM : topiramate, VPA : valproate

*careful switch between LTG and VPA.

FIG. 2. Choice of antiepileptic drugs in elderly

EPILEPSY IN THE ELDERLY

Despite preliminary study on a small group of

elderly patients (Kutluay et al. 2003), the use of

oxcarbazepine is more controversial in old people

because an elevated risk of significant hyponatraemia (< 125 mmol/l). When used in elderly people, a careful evaluation of sodium level should be

done, especially if oxcarbazepine is associated with

diuretics, NSAIDs or carbamazepine and in the

presence hyponatraemia related symptoms

(Schmidt et al. 2001)

Up to now, there is no assessment on the efficacy and the tolerance of pregabalin and tiagabine in

old people.

Conclusion

Epileptic seizures are common in elderly people.

They are frequently under- or over-diagnosed. An

extensive diagnostic work-up is sometimes necessary to rule out imitators of epilepsy and to confirm the epileptic origin of the seizure. Due to the

predominance of cerebrovascular aetiology in this

population, a screening for cardio-vascular risk factors should be proposed when there is no evident

cause to the seizure.

Unlike in the younger, a first unprovoked seizure

should be more often treated. The decision to start

a treatment must take into account the balance

between advantages and side effects of the drug.

The used drug must preferably be well tolerated

without important drug interactions. The treatment

should be administrated slowly and at the lowest

necessary dosage. Despite these precautionary

measures, surveillance of potential side effects

remains necessary.

REFERENCES

HAUSER W. A., ANNEGERS J. F., KURLAND L. T. Incidence

of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester,

Minnesota : 1935-1984. Epilepsia, 1993, 34 :

453-468.

SANDER J. W., HART Y. M., JOHNSON A. L., SHORVON S. D.

National General Practice Study of Epilepsy :

newly diagnosed epileptic seizures in a general

population. Lancet, 1990, 336 : 1267-1271.

RAMSAY R. E., ROWAN A. J., PRYOR F. M. Special considerations in treating the elderly patient with epilepsy. Neurology, 2004, 62 : 24S-29.

DRURY I., BEYDOUN A. Pitfalls of EEG interpretation in

epilepsy. Neurol. Clin., 1993, 11 : 857-881.

SANTAMARIA J., CHIAPPA K. H. The EEG of drowsiness in

normal adults. J. Clin. Neurophysiol., 1987, 4 :

327-382.

DAM A. M., FUGLSANG-FREDERIKSEN A., SVARREOLSEN U., DAM M. Late-onset epilepsy : etiologies, types of seizure, and value of clinical investigation, EEG, and computerized tomography

scan. Epilepsia, 1985, 26 : 227-231.

HENNY C., DESPLAND P. A., REGLI F. Premire crise

pileptique aprs lge de 60 ans : tiologie,

115

prsentation clinique et EEG. Schweiz. Med.

Wochenschr., 1990, 120 : 787-792.

DRURY I., BEYDOUN A. Interictal epileptiform activity in

elderly patients with epilepsy. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol., 1998, 106 : 369-373.

LOISEAU J., CRESPEL A., PICOT M. C., DUCHE B.,

AYRIVIE N. et al. Idiopathic generalized epilepsy

of late onset. Seizure, 1998, 7 : 485-487.

HIYOSHI T., YAGI K. Epilepsy in the elderly. Epilepsia,

2000, 41 Suppl 9 : 31-35.

GASTAUT H. [Individualization of so-called benign and

functional epilepsy at different ages. Appraisal of

variations corresponding the predisposition for

epilepsy at these ages]. Rev. Electroencephalogr.

Neurophysiol. Clin, 1981, 11 : 346-366.

GASTAUT H. Benign or functional (versus organic)

epilepsies in different stages of life : an analysis

of the correpsonding age-related variations in the

predisposition to epilepsy. In : Henri Gastaut and

the Marseilles schools contribution to the neurosciences (EEG Suppl. No 35). BROUGHTON R. J.

(ed.). Amsterdam : Elsevier Biomedical Press,

1982, 17-44.

SUNG C. Y., CHU N. S. Status epilepticus in the elderly :

etiology, seizure type and outcome. Acta Neurol.

Scand., 1989, 80 : 51-56.

LOISEAU J., LOISEAU P., DUCHE B., GUYOT M.,

DARTIGUES J. F. et al. A survey of epileptic disorders in southwest France : seizures in elderly

patients. Ann. Neurol., 1990, 27 : 232-237.

BERGES S., MOULIN T., BERGER E., TATU L., SABLOT D.

et al. Seizures and epilepsy following strokes :

recurrence factors. Eur. Neurol., 2000, 43 : 38.

LOUIS S., MCDOWELL F. Epileptic seizures in nonembolic cerebral infarction. Arch. Neurol., 1967, 17 :

414-418.

KILPATRICK C. J., DAVIS S. M., HOPPER J. L.,

ROSSITER S. C. Early seizures after acute stroke.

Risk of late seizures. Arch. Neurol., 1992, 49 :

509-511.

ARBOIX A., GARCIA-EROLES L., MASSONS J. B.,

OLIVERES M., COMES E. Predictive factors of early

seizures after acute cerebrovascular disease.

Stroke, 1997, 28 : 1590-1594.

REITH J., JORGENSEN H. S., NAKAYAMA H.,

RAASCHOU H. O., OLSEN T. S. Seizures in acute

stroke : predictors and prognostic significance.

The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke, 1997, 28 :

1585-1589.

BURN J., DENNIS M., BAMFORD J., SANDERCOCK P.,

WADE D. et al. Epileptic seizures after a first

stroke : the Oxfordshire Community Stroke

Project. BMJ, 1997, 315 : 1582-1587.

SO E. L., ANNEGERS J. F., HAUSER W. A., OBRIEN P. C.,

WHISNANT J. P. Population-based study of seizure

disorders after cerebral infarction. Neurology,

1996, 46 : 350-355.

SO E. L., ANNEGERS J. F., HAUSER W. A., OBRIEN P. C.,

WHISNANT J. P. Population-based study of seizure

disorders after cerebral infarction. Neurology,

1996, 46 : 350-355.

GUPTA S. R., NAHEEDY M. H., ELIAS D., RUBINO F. A.

Postinfarction seizures. A clinical study. Stroke,

1988, 19 : 1477-1481.

116

M. OSSEMANN ET AL.

KILPATRICK C. J., DAVIS S. M., HOPPER J. L.,

ROSSITER S. C. Early seizures after acute stroke.

Risk of late seizures. Arch. Neurol., 1992, 49 :

509-511.

MILANDRE L., BROCA P., SAMBUC R., KHALIL R. Les crises

pilepstiques au cours at au dcours des accidents

crbrovasculaires. Analyse clinique de 78 cas.

Rev. Neurol. (Paris), 1992, 148 : 767-772.

OSSEMANN M. Crises pileptiques et pilepsies dorigine

vasculaire : caractristiques cliniques, lectroencphalographiques et scannographiques.

Rev. Neurol. (Paris), 2002, 158 : 256-259.

CLEARY P., SHORVON S., TALLIS R. Late-onset seizures as

a predictor of subsequent stroke. Lancet, 2004,

363 : 1184-1186.

HAUSER W. A., MORRIS M. L., HESTON L. L.,

ANDERSON V. E. Seizures and myoclonus in

patients with Alzheimers disease. Neurology,

1986, 36 : 1226-1230.

HESDORFFER D. C., HAUSER W. A., ANNEGERS J. F.,

KOKMEN E., ROCCA W. A. Dementia and adultonset unprovoked seizures. Neurology, 1996, 46 :

727-730.

HAUSER W. A., RICH S. S., ANNEGERS J. F.,

ANDERSON V. E. Seizure recurrence after a 1st

unprovoked seizure : an extended follow-up.

Neurology, 1990, 40 : 1163-1170.

ROCCA W. A., SHARBROUGH F. W., HAUSER W. A.,

ANNEGERS J. F., SCHOENBERG B. S. Risk factors for

complex partial seizures : a population-based

case-control study. Ann. Neurol., 1987, 21 : 2231.

HAUSER W. A., RICH S. S., ANNEGERS J. F.,

ANDERSON V. E. Seizure recurrence after a 1st

unprovoked seizure : an extended follow-up.

Neurology, 1990, 40 : 1163-1170.

VAN DONSELAAR C. A., GEERTS A. T., SCHIMSHEIMER R. J.

Idiopathic first seizure in adult life : who should

be treated ? BMJ, 1991, 302 : 620-623.

FIRST GROUP. Randomized clinical trial on the efficacy of

antiepileptic drugs in reducing the risk of relapse

after a first unprovoked tonic-clonic seizure. First

Seizure Trial Group (FIR.S.T. Group). Neurology,

1993, 43 : 478-483.

DE BORCHGRAVE V., DELVAUX V., DE TOURCHANINOFF M.,

DUBRU J. M., GHARIANI S. et al. Therapeutic strategies in the choice of antiepileptic drugs. Acta

Neurol. Belg., 2002, 102 : 6-10.

CHRISTIANSEN C., RODBRO P., LUND M. Incidence of anticonvulsant osteomalacia and effect of vitamin D :

controlled therapeutic trial. Br. Med. J., 1973, 4 :

695-701.

LEGROS B., BOTTIN P., DE B., V, DELCOURT C., DE

TOURTCHANINOFF M. et al. Therapeutic issues in

women with epilepsy. Acta Neurol Belg., 2003,

103 : 135-139.

TUDUR S. C., MARSON A. G., WILLIAMSON P. R. Phenytoin

versus valproate monotherapy for partial onset

seizures and generalized onset tonic-clonic

seizures. Cochrane. Database. Syst. Rev.,

2001,CD001769.

FRENCH J. A., KANNER A. M., BAUTISTA J., ABOUKHALIL B., BROWNE T. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs I : treatment

of new onset epilepsy : report of the Therapeutics

and Technology Assessment Subcommittee and

Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American

Academy of Neurology and the American

Epilepsy Society. Neurology, 2004, 62 : 12521260.

BRODIE M. J., OVERSTALL P. W., GIORGI L. Multicentre,

double-blind, randomised comparison between

lamotrigine and carbamazepine in elderly patients

with newly diagnosed epilepsy. The UK

Lamotrigine Elderly Study Group. Epilepsy Res.,

1999, 37 : 81-87.

ROWAN A. J., RAMSAY R. E., COLLINS J. F., PRYOR F.,

BOARDMAN K. D. et al. New onset geriatric epilepsy : a randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. Neurology, 2005, 64 :

1868-1873.

GROSELJ J., GUERRINI R., VAN OENE J., LAHAYE M.,

SCHREINER A. et al. Experience with topiramate

monotherapy in elderly patients with recent-onset

epilepsy. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 2005,

112 : 144-150.

CHADWICK D. W., ANHUT H., GREINER M. J.,

ALEXANDER J., MURRAY G. H. et al. A double-blind

trial of gabapentin monotherapy for newly diagnosed partial seizures. International Gabapentin

Monotherapy Study Group 945-77. Neurology,

1998, 51 : 1282-1288.

CRAMER J. A., LEPPIK I. E., RUE K. D., EDRICH P.,

KRAMER G. Tolerability of levetiracetam in elderly patients with CNS disorders. Epilepsy

Research, 2003, 56 : 135-145.

FERRENDELLI J. A., FRENCH J., LEPPIK I., MORRELL M. J.,

HERBEUVAL A. et al. Use of levetiracetam in a

population of patients aged 65 years and older : a

subset analysis of the KEEPER trial. Epilepsy &

Behavior, 2003, 4 : 702-709.

ALSAADI T. M., KOOPMANS S. U. Z. A., APPERSON M. I. C. H., FARIAS S. A. R. A. Levetiracetam

monotherapy for elderly patients with epilepsy.

Seizure, 2004, 13 : 58-60.

KUTLUAY E., MCCAGUE K., DSOUZA J., BEYDOUN A.

Safety and tolerability of oxcarbazepine in elderly patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav., 2003,

4 : 175-180.

SCHMIDT D., ARROYO S., BAULAC M., DAM M., DULAC O.

et al. Recommendations on the clinical use of

oxcarbazepine in the treatment of epilepsy : a

consensus view. Acta Neurol. Scand., 2001, 104 :

167-170.

Dr. M. OSSEMANN,

Service de neurologie,

Cliniques Universitaires UCL de Mont-Godinne,

Avenue Gaston Thrasse 1,

B-5530 Yvoir (Belgium).

E-mail : ossemann@nchm.ucl.ac.be.

You might also like

- Rattan 2008Document6 pagesRattan 2008jessicaNo ratings yet

- Blakytny 2009Document11 pagesBlakytny 2009jessicaNo ratings yet

- Reiner2017 PDFDocument8 pagesReiner2017 PDFjessicaNo ratings yet

- Innovation in Healthcare Delivery Systems FrameworkDocument20 pagesInnovation in Healthcare Delivery Systems FrameworkRirin NurmandhaniNo ratings yet

- 1730 6013 3 PBDocument4 pages1730 6013 3 PBjessicaNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Foot Infection: Antibiotic Therapy and Good Practice RecommendationsDocument10 pagesDiabetic Foot Infection: Antibiotic Therapy and Good Practice RecommendationsjessicaNo ratings yet

- Reiner2017 PDFDocument8 pagesReiner2017 PDFjessicaNo ratings yet

- Glaude Mans 2015Document43 pagesGlaude Mans 2015jessicaNo ratings yet

- 6 Step Problem SolvingDocument9 pages6 Step Problem SolvingjessicaNo ratings yet

- Ibnt 06 I 2 P 229Document4 pagesIbnt 06 I 2 P 229jessicaNo ratings yet

- Proliferation Inhibition and Apoptosis Induction of Imatinib-Resistant Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells Via PPP2R5C Down-RegulationDocument12 pagesProliferation Inhibition and Apoptosis Induction of Imatinib-Resistant Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells Via PPP2R5C Down-RegulationjessicaNo ratings yet

- Guideline MpsDocument15 pagesGuideline MpsjessicaNo ratings yet

- NT Sep13Document20 pagesNT Sep13jessicaNo ratings yet

- 10 1001@jama 2017 11700Document2 pages10 1001@jama 2017 11700jessicaNo ratings yet

- TB and HIV - Co-Infection, Diagnosis & TreatmentDocument5 pagesTB and HIV - Co-Infection, Diagnosis & TreatmentjessicaNo ratings yet

- Comparing Radiological Features of Pulmonary Tuberculosis With and Without Hiv Infection 2155 6113.1000188Document3 pagesComparing Radiological Features of Pulmonary Tuberculosis With and Without Hiv Infection 2155 6113.1000188Riot Riot AdjaNo ratings yet

- Clinical and Radiographic Manifestations and Treatment Outcome of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in The Elderly in Khuzestan, Southwest IranDocument6 pagesClinical and Radiographic Manifestations and Treatment Outcome of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in The Elderly in Khuzestan, Southwest IranjessicaNo ratings yet

- Ifnγ-Producing Cd4 T Lymphocytes: The Double-Edged Swords In TuberculosisDocument7 pagesIfnγ-Producing Cd4 T Lymphocytes: The Double-Edged Swords In TuberculosisjessicaNo ratings yet

- 50 Supplement - 3 S223 PDFDocument8 pages50 Supplement - 3 S223 PDFjessicaNo ratings yet

- HBV Easl 2017Document57 pagesHBV Easl 2017jessica100% (1)

- Microscopy As A Diagnostic Tool in Pulmonary Tuberculosis: SciencedirectDocument6 pagesMicroscopy As A Diagnostic Tool in Pulmonary Tuberculosis: SciencedirectjessicaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Mentoring 10 Kegawatan Jantung Oleh Dr. Ika Prasetya Wijayasppd KKV Finasim FacpDocument48 pagesClinical Mentoring 10 Kegawatan Jantung Oleh Dr. Ika Prasetya Wijayasppd KKV Finasim FacpGede GiriNo ratings yet

- Alkindi 2016Document3 pagesAlkindi 2016jessicaNo ratings yet

- Getachew4352013BJMMR7308 1Document10 pagesGetachew4352013BJMMR7308 1jessicaNo ratings yet

- How To Write An Academic JournalDocument113 pagesHow To Write An Academic JournaljessicaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0196064410013223 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S0196064410013223 MainjessicaNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Tuberculosis and HIV Coinfections in Singapore, 2000 2014Document6 pagesEpidemiology of Tuberculosis and HIV Coinfections in Singapore, 2000 2014jessicaNo ratings yet

- Role of CultureDocument6 pagesRole of CulturejessicaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0422763816300796 Main PDFDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0422763816300796 Main PDFjessicaNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Tuberculosis and HIV Coinfections in Singapore, 2000 2014Document6 pagesEpidemiology of Tuberculosis and HIV Coinfections in Singapore, 2000 2014jessicaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Action Plan On Medical and Nursing: Resource ReqmtsDocument15 pagesAction Plan On Medical and Nursing: Resource ReqmtsJude Mathew100% (2)

- The Health Bank (THB) Connected Care Program A Pilot Study of Remote Monitoring For The Management of Chronic Conditions Focusing On DiabetesDocument5 pagesThe Health Bank (THB) Connected Care Program A Pilot Study of Remote Monitoring For The Management of Chronic Conditions Focusing On DiabetesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Suicide Among The YouthDocument21 pagesSuicide Among The YouthSahil MirNo ratings yet

- Burton's Microbiology For The Health Sciences: Diagnosing Infectious DiseasesDocument35 pagesBurton's Microbiology For The Health Sciences: Diagnosing Infectious DiseasesJehu C LanieNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Preventing HealthcareDocument78 pagesGuidelines For Preventing HealthcareppeterarmstrongNo ratings yet

- How To Take Your Blood Pressure at HomeDocument1 pageHow To Take Your Blood Pressure at HomePratyush VelaskarNo ratings yet

- Medifocus April 2007Document61 pagesMedifocus April 2007Pushpanjali Crosslay HospitalNo ratings yet

- Module 10 2023Document42 pagesModule 10 2023jamsineNo ratings yet

- Inpatient Psychiatric Unit Patient HandbookDocument7 pagesInpatient Psychiatric Unit Patient HandbookJuanCarlos Yogi0% (1)

- 10 Early Signs of LupusDocument3 pages10 Early Signs of LupusJessica RomeroNo ratings yet

- Solid-Waste-Management 2858710 PowerpointDocument20 pagesSolid-Waste-Management 2858710 PowerpointGopi AravindNo ratings yet

- Liver Cirrhosis: Causes, Complications and ManagementDocument55 pagesLiver Cirrhosis: Causes, Complications and ManagementAnonymous vUEDx8100% (1)

- Petronas Gas PGB PDFDocument34 pagesPetronas Gas PGB PDFAhmad Aiman100% (5)

- Safety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance / Preparation and of The Company / UndertakingDocument3 pagesSafety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance / Preparation and of The Company / UndertakingnbagarNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Dentistry Consent For Dental ProceduresDocument2 pagesPediatric Dentistry Consent For Dental ProceduresNishtha KumarNo ratings yet

- Vdoc - Pub End of Life Care in Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument251 pagesVdoc - Pub End of Life Care in Cardiovascular Diseasericardo valtierra diaz infanteNo ratings yet

- CHED Student Logbook for Surgery ProceduresDocument2 pagesCHED Student Logbook for Surgery ProceduresMarieCrisNo ratings yet

- Pai NMJI 2004 Systematic Reviews Illustrated Guide3Document10 pagesPai NMJI 2004 Systematic Reviews Illustrated Guide3mphil.rameshNo ratings yet

- 2016 - Are There Subconcussive Neuropsychological Effects in Youth Sports? An Exploratory Study of High - and Low-Contact SportsDocument8 pages2016 - Are There Subconcussive Neuropsychological Effects in Youth Sports? An Exploratory Study of High - and Low-Contact SportsRaúl VerdugoNo ratings yet

- Marginal Ulcer, A Case StudyDocument4 pagesMarginal Ulcer, A Case StudySailaja NandennagariNo ratings yet

- Effects of Drug Abuse on Health and SocietyDocument9 pagesEffects of Drug Abuse on Health and SocietyAditya guptaNo ratings yet

- Development of Keloid After Surgery & Its TreatmentDocument2 pagesDevelopment of Keloid After Surgery & Its TreatmentInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Labor AssessmentDocument14 pagesLabor AssessmentShay DayNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Liver Enzyme Tests - A Rapid GuideDocument3 pagesInterpretation of Liver Enzyme Tests - A Rapid Guidesserggios100% (2)

- Are Gadgets and Technology Good or Bad For Students?Document2 pagesAre Gadgets and Technology Good or Bad For Students?Angel C.No ratings yet

- FCA FormatDocument4 pagesFCA FormatAlexa PasionNo ratings yet

- Digital Rectal ExaminationDocument7 pagesDigital Rectal ExaminationAla'a Emerald AguamNo ratings yet

- Aortic AneurysmDocument26 pagesAortic Aneurysmchetanm2563100% (1)

- Discharge PlanDocument2 pagesDischarge PlanabraNo ratings yet

- BHW OrdinanceDocument3 pagesBHW OrdinanceAlfred Benedict Suarez100% (2)