Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Legal Standing

Uploaded by

Boy Kakak TokiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Legal Standing

Uploaded by

Boy Kakak TokiCopyright:

Available Formats

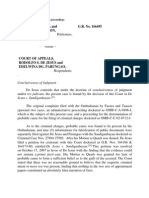

Petitioners lack locus standi

Locus standi or legal standing requires a personal stake in the outcome of the

controversy as to assure that concrete adverseness which sharpens the

presentation of issues upon which the court so largely depends for illumination of

difficult constitutional questions.[11]

Anak Mindanao Party-List Group v. The Executive Secretary [12] summarized the

rule on locus standi, thus:

Locus standi or legal standing has been defined as a personal and

substantial interest in a case such that the party has sustained or will

sustain direct injury as a result of the governmental act that is being

challenged. The gist of the question on standing is whether a party

alleges such personal stake in the outcome of the controversy as to

assure that concrete adverseness which sharpens the presentation of

issues upon which the court depends for illumination of difficult

constitutional questions.

[A] party who assails the constitutionality of a statute must have a direct

and personal interest. It must show not only that the law or any

governmental act is invalid, but also that it sustained or is in immediate

danger of sustaining some direct injury as a result of its

enforcement, and not merely that it suffers thereby in some indefinite

way. It must show that it has been or is about to be denied some right or

privilege to which it is lawfully entitled or that it is about to be subjected

to some burdens or penalties by reason of the statute or act complained

of.

For a concerned party to be allowed to raise a constitutional question, it

must show that (1) it has personally suffered some actual or

threatened injury as a result of the allegedly illegal conduct of the

government, (2) the injury is fairly traceable to the challenged action,

and (3) the injury is likely to be redressed by a favorable action.

(emphasis and underscoring supplied.)

Petitioner-organizations assert locus standi on the basis of being suspected

communist fronts by the government, especially the military; whereas individual

petitioners invariably invoke the transcendental importance doctrine and their

status as citizens and taxpayers.

While Chavez v. PCGG[13] holds that transcendental public importance dispenses

with the requirement that petitioner has experienced or is in actual danger of

suffering direct and personal injury, cases involving the constitutionality

of penal legislation belong to an altogether different genus of constitutional

litigation. Compelling State and societal interests in the proscription of harmful

conduct, as will later be elucidated, necessitate a closer judicial scrutiny of locus

standi.

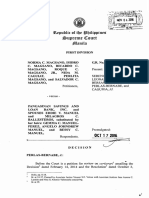

Besides, petitioners have no locus standi or legal standing. Locus standi or legal standing is

defined as:

x x x a personal and substantial interest in the case such that the party has sustained or will

sustain a direct injury as a result of the governmental act that is being challenged. The term

"interest" means a material interest, an. interest in issue affected by the decree, as

distinguished from mere interest in the question involved, or a mere incidental interest. The gist

of the question of standing is whether a party alleges such personal stake in the outcome of the

controversy as to assure that concrete adverseness which sharpens the presentation of issues

upon which the court depends for illumination of difficult constitutional questions.

12

In this case, petitioners failed to allege personal or substantial interest . in the questioned

governmental act which is the issuance of COMELEC Minute Resolution No. 12-0859, which

confirmed the re-computation of the allocation of seats of the Party-List System of

Representation in the House of Representatives in the 10 May 2010 Automated National and

Local Elections. Petitioner Association of Flood Victims is not even a party-list candidate in the

10 May 2010 elections, and thus, could not have been directly affected by COMELEC Minute

Resoluti

You might also like

- For: Juan de La Cruz, From: Karla Rose Gutierrez Date: September 9, 2015 RE: Illegal Dismissal of A Red Cross Employee InquiryDocument3 pagesFor: Juan de La Cruz, From: Karla Rose Gutierrez Date: September 9, 2015 RE: Illegal Dismissal of A Red Cross Employee InquiryLeika MercedNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Case DigestDocument23 pagesAgrarian Case DigestJim Jorjohn SulapasNo ratings yet

- AFFIDAVIT OF UNDERTAKING Special EnlismentDocument2 pagesAFFIDAVIT OF UNDERTAKING Special EnlismentQueen GarciaNo ratings yet

- DOAS HOlgadoDocument7 pagesDOAS HOlgadoWendell MaunahanNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Upholds DAR Ruling on Land Ownership DisputeDocument3 pagesSupreme Court Upholds DAR Ruling on Land Ownership DisputeAysNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction Is Determined by The Allegations in The ComplaintDocument4 pagesJurisdiction Is Determined by The Allegations in The Complaintkrissy liNo ratings yet

- Non-Forum Shopping Verification CertificateDocument1 pageNon-Forum Shopping Verification CertificateMarvin AlvisNo ratings yet

- 1111SOCEForms ForCandidatesWF PDFDocument1 page1111SOCEForms ForCandidatesWF PDFCez Flores TalatalaNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit on AssaultDocument3 pagesJudicial Affidavit on AssaultJeremiahN.CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Demurer To EvidenceDocument13 pagesDemurer To EvidenceDax MonteclarNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit Antonio LunaDocument5 pagesJudicial Affidavit Antonio LunaToniNarcisoNo ratings yet

- Due Process Under The Labor Code Involves Two AspectsDocument3 pagesDue Process Under The Labor Code Involves Two AspectsCaroline Claire BaricNo ratings yet

- Formal Offer of Documentary ExhibitsDocument4 pagesFormal Offer of Documentary ExhibitsMikko AcubaNo ratings yet

- Joint Counter-Affidavit Refutes Slander, Threat ChargesDocument11 pagesJoint Counter-Affidavit Refutes Slander, Threat ChargesGabriel SincoNo ratings yet

- Mr. Joel B. Jopia International Elevator & Equipment, IncDocument1 pageMr. Joel B. Jopia International Elevator & Equipment, IncRonell SolijonNo ratings yet

- Defamation ClaimDocument13 pagesDefamation ClaimCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Child AbuseDocument3 pagesChild AbuseHerbert Shirov Tendido SecurataNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Desistance - Rizel A. LacuarinDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Desistance - Rizel A. LacuarinKen Rinehart V. SurNo ratings yet

- Position Paper Ver 2Document10 pagesPosition Paper Ver 2Delmer Riparip100% (1)

- Sworn StatementDocument2 pagesSworn StatementRenzo JamerNo ratings yet

- Lacson vs. LacsonDocument5 pagesLacson vs. LacsonCharmaine Reyes FabellaNo ratings yet

- G.R. Nos. L-21528 and L-21529 March 28, 1969 ROSAURO REYES, Petitioner, The People of The Philippines, RespondentDocument22 pagesG.R. Nos. L-21528 and L-21529 March 28, 1969 ROSAURO REYES, Petitioner, The People of The Philippines, RespondentJas Em Bej100% (1)

- Accion Publician Judicial AffidavitDocument6 pagesAccion Publician Judicial AffidavitMel Phildrich Defiño GanuhayNo ratings yet

- Estrada vs. BadoyDocument17 pagesEstrada vs. BadoyCMLNo ratings yet

- Libel ElementsDocument4 pagesLibel ElementsromarcambriNo ratings yet

- Res Judicata in Administrative ProceedingsDocument7 pagesRes Judicata in Administrative Proceedingsninpourepa100% (2)

- Regional Trial Court: - VersusDocument3 pagesRegional Trial Court: - VersusBfp-ncr MandaluyongNo ratings yet

- 2020 Counter Affdavit DAISY OCAMPODocument3 pages2020 Counter Affdavit DAISY OCAMPOLeoNo ratings yet

- Counter AffidavitDocument5 pagesCounter AffidavitTim PuertosNo ratings yet

- People Vs Januario - 98552 - February 7, 1997 - JDocument20 pagesPeople Vs Januario - 98552 - February 7, 1997 - JTrexPutiNo ratings yet

- Regional Trial CourtDocument5 pagesRegional Trial CourtNicole SantoallaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit - BDO Quitclaim GCQ 2020Document1 pageAffidavit - BDO Quitclaim GCQ 2020Undo ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- Navales vs. Costanilla, Et Al. - COMPLAINTDocument5 pagesNavales vs. Costanilla, Et Al. - COMPLAINTfortunecNo ratings yet

- Rejoinder AffidavitDocument3 pagesRejoinder AffidavitNeil bryan MoninioNo ratings yet

- Accessory penalties for crimes in the PhilippinesDocument1 pageAccessory penalties for crimes in the PhilippinesMonalizts D.No ratings yet

- Sample. New Judicial AffidavitDocument5 pagesSample. New Judicial AffidavitsuckerforsoccerNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit Isidro TorregozaDocument2 pagesJudicial Affidavit Isidro TorregozaCharles CornelNo ratings yet

- Philippine heirs seek reconveyance of excess land areaDocument11 pagesPhilippine heirs seek reconveyance of excess land areaEdward Rey EbaoNo ratings yet

- Revised Ortega Lecture Notes On Criminal Law 2.1Document83 pagesRevised Ortega Lecture Notes On Criminal Law 2.1Hazel Abagat-DazaNo ratings yet

- Collateral Attack On Certificate of Title Is Not AllowedDocument2 pagesCollateral Attack On Certificate of Title Is Not Allowedyurets929No ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Office of The President Optical Media Board Legal Services Division Quezon City Optical Media BoardDocument8 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Office of The President Optical Media Board Legal Services Division Quezon City Optical Media BoardRichard GomezNo ratings yet

- Cadavedo vs. Atty. Lacaya, A.C. No. 173188, Jan. 15, 2014Document15 pagesCadavedo vs. Atty. Lacaya, A.C. No. 173188, Jan. 15, 2014Tim SangalangNo ratings yet

- Judicial Counter-Affidavit of Nicole Leonor Atilano PonDocument5 pagesJudicial Counter-Affidavit of Nicole Leonor Atilano PonJojo Navarro100% (1)

- Court upholds prosecution for defamation, attempted homicideDocument7 pagesCourt upholds prosecution for defamation, attempted homicideMary Licel RegalaNo ratings yet

- NCR CommentDocument7 pagesNCR CommentJil MacasaetNo ratings yet

- JA JEAN RODRIGUEZ FinalDocument7 pagesJA JEAN RODRIGUEZ FinaljustineNo ratings yet

- Accion Reivindicatoria Is An Action Whereby Plaintiff Alleges Ownership Over A Parcel ofDocument2 pagesAccion Reivindicatoria Is An Action Whereby Plaintiff Alleges Ownership Over A Parcel ofJosiah DavidNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Two Disinterested Persons (For Delayed Birth Cert)Document1 pageAffidavit of Two Disinterested Persons (For Delayed Birth Cert)RmLyn MclnaoNo ratings yet

- Municipal Trial Court in Cities First Judicial Region: Page 1 of 5Document5 pagesMunicipal Trial Court in Cities First Judicial Region: Page 1 of 5sonskiNo ratings yet

- 6 Purefoods Vs NLRC G.R. No. 122653Document5 pages6 Purefoods Vs NLRC G.R. No. 122653Lonalyn Avila Acebedo100% (1)

- Affidavit of ComplaintDocument2 pagesAffidavit of ComplaintNaim SubaNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration: Office of The City ProsecutorDocument8 pagesMotion For Reconsideration: Office of The City ProsecutorDanpatz Garcia100% (1)

- Galvante v. Casimiro, G.R. No. 162808, April 22, 2008, 552 SCRA 304Document5 pagesGalvante v. Casimiro, G.R. No. 162808, April 22, 2008, 552 SCRA 304Emil Bautista100% (1)

- Draft Complaint Unlawful DetainerDocument7 pagesDraft Complaint Unlawful DetainermgabatangcarmeloNo ratings yet

- Narrative - Affidavit: Republic of The Philippines) City of Talisay, Cebu ) S.SDocument1 pageNarrative - Affidavit: Republic of The Philippines) City of Talisay, Cebu ) S.SMaria Odette BlancoNo ratings yet

- Locus Standi: EnriquezDocument6 pagesLocus Standi: EnriquezOnireblabas Yor OsicranNo ratings yet

- Legal Standing NotesDocument1 pageLegal Standing NotesBoyet-Daday EnageNo ratings yet

- "Locus Standi" Strictly Construed - G.R. No. 193978Document3 pages"Locus Standi" Strictly Construed - G.R. No. 193978Abayabay KarlaNo ratings yet

- Requisites For The Exercise of JUDICIAL REVIEW. - G.R. No. 164987Document2 pagesRequisites For The Exercise of JUDICIAL REVIEW. - G.R. No. 164987Mark Pame Agapito ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Notes On Requisites of Judicial ReviewDocument3 pagesNotes On Requisites of Judicial ReviewdindoNo ratings yet

- Brief For Appellee-Defendant: Court of AppealsDocument1 pageBrief For Appellee-Defendant: Court of AppealsBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Legal Forms 2Document17 pagesLegal Forms 2LukeCarterNo ratings yet

- Invitation Letter - Rural Development InstituteDocument1 pageInvitation Letter - Rural Development InstituteBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Sales 1Document2 pagesSales 1Boy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Interpreting intent in property agreementsDocument1 pageInterpreting intent in property agreementsBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- ResumeDocument2 pagesResumeBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- BIR Form 1905 PDFDocument2 pagesBIR Form 1905 PDFHeidi85% (13)

- RULE 121 Report Criminal ProcedureDocument12 pagesRULE 121 Report Criminal ProcedureBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

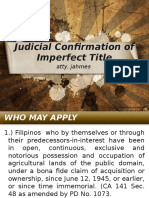

- Land Titles - Judicial Confirmation of Imperfect TItle-Orig Reg StepsDocument53 pagesLand Titles - Judicial Confirmation of Imperfect TItle-Orig Reg StepsBoy Kakak Toki86% (7)

- SpeechDocument3 pagesSpeechBoy Kakak Toki100% (1)

- SPECPRO Review CasesDocument76 pagesSPECPRO Review CasesBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Report 1910-1918 BalinduaDocument5 pagesReport 1910-1918 BalinduaBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Sex Educ and Teen PregnancyDocument10 pagesSex Educ and Teen PregnancyBoy Kakak Toki0% (1)

- Elections EXAMS LakasDocument19 pagesElections EXAMS LakasBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Bank of Commerce Vs Marilyn NIteDocument3 pagesBank of Commerce Vs Marilyn NIteBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Persons and Family Relations CasesDocument2 pagesPersons and Family Relations CasesBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Guerrero vs. Director, Land Management BureauDocument7 pagesBenjamin Guerrero vs. Director, Land Management BureauBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Original Registration 13 Steps - Land TitlesDocument42 pagesOriginal Registration 13 Steps - Land TitlesBoy Kakak Toki100% (14)

- Fundamental Principles and Policies of Labor LawsDocument1 pageFundamental Principles and Policies of Labor LawsBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- April Dec 2015 CasesDocument4 pagesApril Dec 2015 CasesBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Direct Testimony of Marco Polongco Prac CourtDocument7 pagesDirect Testimony of Marco Polongco Prac CourtBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Marcos Vs Marcos FACTS: Petitioner Brenda Marcos and Respondent Wilson Marcos WereDocument6 pagesMarcos Vs Marcos FACTS: Petitioner Brenda Marcos and Respondent Wilson Marcos WereBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- POLITICAL LAW 1-8Document142 pagesPOLITICAL LAW 1-8schating2No ratings yet

- Showing That The Defendants Are About To DepartDocument3 pagesShowing That The Defendants Are About To DepartBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Consti NotesDocument23 pagesConsti NotesBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Taxcases 1Document16 pagesTaxcases 1Boy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- CivPro Codal NotesDocument4 pagesCivPro Codal NotesBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Consti NotesDocument2 pagesConsti NotesBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Principles and Policies of Labor LawsDocument1 pageFundamental Principles and Policies of Labor LawsBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Marcos Vs Marcos FACTS: Petitioner Brenda Marcos and Respondent Wilson Marcos WereDocument6 pagesMarcos Vs Marcos FACTS: Petitioner Brenda Marcos and Respondent Wilson Marcos WereBoy Kakak TokiNo ratings yet

- Tax Case Digest - Cir vs. Batangas Transportation Co.Document2 pagesTax Case Digest - Cir vs. Batangas Transportation Co.YourLawBuddyNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Policronio Ureta v. Heirs of Liberato Ureta, 657 SRA 555 (2011)Document2 pagesHeirs of Policronio Ureta v. Heirs of Liberato Ureta, 657 SRA 555 (2011)Kalvin ChesterNo ratings yet

- 2017-02-24 Margarita Mares Rescission LetterDocument1 page2017-02-24 Margarita Mares Rescission Letterapi-360769610No ratings yet

- John V Ballingall 2017 ONCA 579 (Appellant)Document70 pagesJohn V Ballingall 2017 ONCA 579 (Appellant)Omar Ha-RedeyeNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Bar Council Rules on Advocate ConductDocument2 pagesPakistan Bar Council Rules on Advocate ConductUroosha IsmailNo ratings yet

- Apply for funding with ID numberDocument2 pagesApply for funding with ID numberThubelihle HadebeNo ratings yet

- Go-Yu vs. YuDocument14 pagesGo-Yu vs. Yuchristian villamanteNo ratings yet

- Flores vs. People, 862 SCRA 370Document21 pagesFlores vs. People, 862 SCRA 370Athena Jeunnesse Mae Martinez TriaNo ratings yet

- Survey Act 25 of 1961Document19 pagesSurvey Act 25 of 1961opulitheNo ratings yet

- Magsano Vs Pangasinan SavingsDocument12 pagesMagsano Vs Pangasinan SavingsCyber QuestNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez Vs PonferradaDocument3 pagesRodriguez Vs PonferradaRenson YuNo ratings yet

- United States v. Robert Neal Raines, 812 F.2d 1402, 4th Cir. (1987)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Robert Neal Raines, 812 F.2d 1402, 4th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Composer Agreement - London at Night V2Document2 pagesComposer Agreement - London at Night V2KeepItTidyNo ratings yet

- Price Theory and Applications 9th Edition Steven Landsburg Solutions ManualDocument9 pagesPrice Theory and Applications 9th Edition Steven Landsburg Solutions ManualMonicaSmithyxwd100% (29)

- OMB Vs EstandarteDocument2 pagesOMB Vs EstandarteAngel Eilise100% (2)

- Will interpretation and estate partition upheldDocument2 pagesWill interpretation and estate partition upheldpja_14100% (1)

- Lect 1 Land LawDocument17 pagesLect 1 Land LawRANDAN SADIQNo ratings yet

- Deed of Sale of MotorcycleDocument6 pagesDeed of Sale of MotorcycleEstelita MiguelNo ratings yet

- RULE 1 To 4Document7 pagesRULE 1 To 4Ma Gloria Trinidad ArafolNo ratings yet

- Dismissal FilingDocument4 pagesDismissal FilingVictor I NavaNo ratings yet

- U.S. Vs Brobst, G.R. No. L-4935Document11 pagesU.S. Vs Brobst, G.R. No. L-4935LASNo ratings yet

- V. COA: Nini Lanto v. COA Topic: Public Office and Responsibility FactsDocument2 pagesV. COA: Nini Lanto v. COA Topic: Public Office and Responsibility FactsPJANo ratings yet

- Sale of Goods Act ExplainedDocument7 pagesSale of Goods Act ExplainediyerlakshmiNo ratings yet

- Digest Alberto V Alberto, Irao V by The BayDocument2 pagesDigest Alberto V Alberto, Irao V by The BayEduardo SalvadorNo ratings yet

- 7 Essential Construction Contract Clauses - 1Document2 pages7 Essential Construction Contract Clauses - 1sfreigaNo ratings yet

- AM No. 03-1-09-SCDocument9 pagesAM No. 03-1-09-SCJena Mae Yumul100% (7)

- PDF Deed of Sale Banca 1 DDDocument2 pagesPDF Deed of Sale Banca 1 DDHazel Nicole TumulakNo ratings yet

- Defining and Measuring Crime and DevianceDocument9 pagesDefining and Measuring Crime and DevianceEileen GeogheganNo ratings yet

- IREDA - LIE Empanelment Letter Valid For 3 YearsDocument9 pagesIREDA - LIE Empanelment Letter Valid For 3 YearsrdvasuNo ratings yet

- Maximino Delgado ComplaintDocument2 pagesMaximino Delgado ComplaintAshley LudwigNo ratings yet