Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FT - Europe Cannot Leave Athens On Its Own

Uploaded by

sleepingkoalaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FT - Europe Cannot Leave Athens On Its Own

Uploaded by

sleepingkoalaCopyright:

Available Formats

FT.com print article http://www.ft.com/cms/s/f1eef94a-1cc9-11df-8d8e-00144feab49a...

COMMENT

Financial OPINION

Close

Europe cannot leave Athens on its own

By Tommaso!Padoa-Schioppa

Published: February 18 2010 20:33 | Last updated: February 18 2010 20:33

For years, Otmar Issing and I worked side by side to make the euro a success, and I think we did. At the European

Central Bank we almost always agreed on the stance of policy. When we could not, the hawk was sometimes me.

Now comes the Greek debt crisis and the declaration by European leaders that they “will take determined and

co-ordinated action, if needed, to safeguard financial stability in the euro area as a whole”. I welcome this

statement; Otmar condemns it.

The spectrum of possible outcomes to this crisis is wide. At the best, the Greek government could win full public

backing for a package that reduces the deficit and restores creditors’ confidence. At the worst, we could see

Greece default, with a domino effect knocking down other countries and even leading to a break-up of the

eurozone. In-between lie many other, more likely outcomes.

In a climate of fear, markets can become as blind and destructive as a natural catastrophe and fail to distinguish

between the errant and the irreproachable, between Greece and the outside. A point could soon be reached where

not to act would invite disaster upon all. We are now so close to such a point that the EU leaders’ statement was a

wise step. Through inaction, virtuous but myopic countries could deal a blow to their own prosperity and stability.

What is needed is not altruism, only enlightened self-interest.

As Mr Issing puts it, the Greek crisis is not a natural catastrophe, it is entirely man-made. To be fair, some of the

blame lies outside Greece, because all EU countries bear a responsibility for failing to exert peer pressure and

refusing to grant the Commission sufficient power and independence, including the power to establish the right

statistics. But the crisis was wrought mainly by Greek hands.

Does it follow that a default would hurt only Greece? Or that “determined and co-ordinated action” would be more

harmful to the eurozone than a default? Obviously not; and Mr Issing carefully stops short of stating the contrary.

He is too good a scholar to forget that economics, unlike theology, is about pros and cons. No one can pretend

that in all possible circumstances a Greek default is – for those outside Greece – economically preferable to

“determined and co-ordinated action”. Probably there is, once again, little disagreement between us on the

economics.

So, why should the EU not help? Because it is not a political union, is the amazing answer – amazing also, note,

because it implicitly approves of domestic bail-outs. The disagreement must, therefore, be about the politics.

(Remember Schumpeter’s answer to a journalist who asked him what economic policy was about: “politics,

politics, politics!”)

True, monetary union came before political union. But it did not come with a promise that there would never be

such a union. Quite to the contrary: the founding fathers wanted the euro primarily as a step towards political

union, knowing little of the overriding technical arguments in its favour. Those who argued against it then on the

grounds that “there can that there could be no monetary union without political union” are precisely those who

should welcome political union now that it finally knocks at the door claiming its rights.

Action is required; but what kind of action? It could range from exerting pressure, to providing liquidity assistance,

to lending money, to making gifts. Everywhere in this crisis – virtuous countries are no exception – we have seen

good and bad policy. The bottom line is that Greece should receive support, but no gifts.

The EU has been appropriately vague on the type of action it would take. Any delicate negotiation involves a

degree of ambiguity, whether we like it or not. Otherwise, public opinion, labour unions, competing political parties

and patriotism can all too easily become inflamed.

What should be made clear to the public is that no country has full sovereignty any longer – not Greece, because

of its misbehaviour, and not even Germany, because of its openness (which is a major source of its prosperity).

Some luck is indispensable, but what matters most is enlightened political leadership backed by good economic

advice. This is needed primarily in Athens, but also very much in Brussels, Berlin, Paris and every other European

capital.

The writer is president of Notre Europe, a former Italian finance minister and a former member of the European

Central Bank’s executive board

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2010. Print a single copy of this article for personal use. Contact us if you wish to print

more to distribute to others.

1 of 2 2/19/10 9:02 AM

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Land Patent - DeclarationDocument1 pageLand Patent - DeclarationAnnette Spendel100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- N-lc-03 HSBC V NSC & City TrustDocument4 pagesN-lc-03 HSBC V NSC & City TrustAndrew Gallardo100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Benedict On Admiralty - PracticeDocument303 pagesBenedict On Admiralty - PracticeRebel XNo ratings yet

- Same Sex Adoption EvDocument5 pagesSame Sex Adoption Evapi-292471795No ratings yet

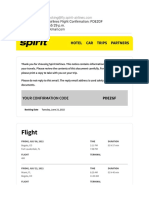

- Modified Spirit Airlines Flight Confirmation PDEZGFDocument7 pagesModified Spirit Airlines Flight Confirmation PDEZGFASTRIDH CHACONNo ratings yet

- Dreams Are Broken Into Three Parts According To The SunnahDocument19 pagesDreams Are Broken Into Three Parts According To The SunnahpakpidiaNo ratings yet

- Lopez vs De Los Reyes: House has power to punish for contemptDocument6 pagesLopez vs De Los Reyes: House has power to punish for contemptSofia MoniqueNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit OngpinDocument3 pagesJudicial Affidavit OngpinRhobee JynNo ratings yet

- Yolanda Mercado Vs AMA, DigestDocument1 pageYolanda Mercado Vs AMA, DigestAlan Gultia100% (1)

- Aliviado Et Al v. P&GDocument2 pagesAliviado Et Al v. P&GVon Lee De LunaNo ratings yet

- The Malay WeddingDocument4 pagesThe Malay WeddingHidayah SallehNo ratings yet

- Negotiable InstrumentsDocument7 pagesNegotiable InstrumentsClaudine SumalinogNo ratings yet

- Industrial Disputes ActDocument2 pagesIndustrial Disputes ActKiran SatijaNo ratings yet

- PrếntationDocument12 pagesPrếntationPXCRNo ratings yet

- Peace Education Ebook 2010Document211 pagesPeace Education Ebook 2010King Gaspar CalmaNo ratings yet

- Drywall ContractDocument5 pagesDrywall ContractRocketLawyerNo ratings yet

- Case BriefDocument11 pagesCase Briefmasroor rehmaniNo ratings yet

- TNS Training ContractDocument3 pagesTNS Training ContractA.K. FernandezNo ratings yet

- BPI Vs Guevara DigestDocument47 pagesBPI Vs Guevara DigestRob ClosasNo ratings yet

- Hungry Wolf: A Wise Old OwlDocument2 pagesHungry Wolf: A Wise Old OwlAnnuar IsmailNo ratings yet

- Eng Passive Voice - SoalDocument8 pagesEng Passive Voice - SoalFiaFallen0% (1)

- Philippine Participation in UN Peace OperationsDocument8 pagesPhilippine Participation in UN Peace Operationsangker arnelNo ratings yet

- LTA LOGISTICS Vs Enrique Varona (Varona Request of Production For Discovery)Document4 pagesLTA LOGISTICS Vs Enrique Varona (Varona Request of Production For Discovery)Enrique VaronaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Murray Francis Hardesty, 166 F.3d 1222, 10th Cir. (1999)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Murray Francis Hardesty, 166 F.3d 1222, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Maximo Abano For Respondents. No Appearance For PetitionerDocument5 pagesMaximo Abano For Respondents. No Appearance For Petitionerclifford tubanaNo ratings yet

- Chekhov Short Story AnalysisDocument2 pagesChekhov Short Story Analysissperera32No ratings yet

- Charles Wesley Ervin, Tomorrow Is Ours: The Trotskyist Movement in India and Ceylon 1935-48, Colombo: Social Scientists' Association, 2006.Document395 pagesCharles Wesley Ervin, Tomorrow Is Ours: The Trotskyist Movement in India and Ceylon 1935-48, Colombo: Social Scientists' Association, 2006.danielgaid100% (1)

- Election Appeals and Free SpeechDocument34 pagesElection Appeals and Free SpeechPranay BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Pakistan-US Relations Historical Analysis After 9/11Document14 pagesPakistan-US Relations Historical Analysis After 9/11tooba mukhtarNo ratings yet