Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Good As Gold: Book Review

Uploaded by

api-277057088Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Good As Gold: Book Review

Uploaded by

api-277057088Copyright:

Available Formats

Page 4

Good as Gold

UNC Charlotte

The UNC Charlotte Urban Educators for Change

Newsletter

Book Review

The Flat World and Education:

How Americas Commitment to Equity Will

Determine Our Future

by Linda Darling-Hammond

Review written by Amber C. Bryant

In her book, The Flat W orld and Education: How A mericas Commitment to Equity Will Determine Our Future, respected educator and researcher, Linda Darling-Hammond, effectively

weaves together research, articles, and studies creating a comprehensive guide to understanding educational inequalities throughout the world. The text provides a close examination of the historical landscape of education in America. It also covers the educational policies and ever-changing legislation that continue to

work toward the demise of equitable schooling. Hammond highlights exemplar practices and bright spots in the world (i.e.,

Finland and Singapore) where education is serving all students

effectively and yielding positive educational outcomes. DarlingHammonds intentions in writing the book are clear as she discusses the problematic truth of our countrys current education

system. The purpose of the text is to explain and support the idea

that the United States needs to move much more decisively than

it has the last quarter century to establish a purposeful, equitable

education system that will prepare all our children for success

and a knowledgebased society. She argues that the education

and economic crisis is one we must teach our way out. Historically speaking, this would be a completely new approach to education for our country .

Darling-Hammond offers evaluation and criticism, but

not without resolutions. Throughout the text, Darling-Hammond

discusses several recommendations for reform including a complete overhaul and reconstruction of teacher preparation programs and better mentoring for beginning teachers. She also suggests increasing and diversifying recruitment and retention efforts.

The book is an excellent text for pre-service and inservice teachers. It would also inform politicians and policymakers about the critical issues in education. The limitations of the

text are its length and complexity which make it an unlikely read

for some parents and practitioners who could benefit from its

information. However, the content is relevant and cohesively

blended together providing an easily comprehensible narrative.

Darling-Hammond uses simplistic diction to explore complex

themes and topics surrounding education, making these topics

accessible to a broad and diverse audience.

2016 International Conference on

Urban Education in Puerto Rico

The Urban Education Collaborative housed in the

College of Education at the University of North Carolina

at Charlotte is pleased to announce the 2nd Biennial International Conference on Urban Education (ICUE) in beautiful San Juan, Puerto Rico. ICUE has strategically been

developed to bring various stakeholders (educators, community members, NGOs, government officials, business

leaders, faith-based officials, and healthcare providers)

together who have a vested interest in improving educational opportunities for students in urban settings around

the globe. As a result, ICUE is the launch of a global

movement in urban education. It is scheduled to take

place in the first week in November 2016. Please continue

to check the official ICUE website at www.theicue.org/ for

updates on this highly anticipated conference.

Old San Juan

The view from El Yunque National Forest

We welcome your questions and comments. Please send them to

Dymilah Hewitt at dhewitt3@uncc.edu.

Twitter: @Urban3d4change

Facebook: Urban Educators for Change

University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Amber Bryant is a doctoral student at UNCC.

Main Campus: 9201 University City Blvd Charlotte NC 28223

The Impact of Personal Beliefs on Teacher Effectiveness

by Courtney Glavich

There have been various reports on

how teacher thinking dramatically affects

teacher effectiveness and student performance

(Pajares, 1992). When future teachers arrive

on college campuses, many already have

predispositions about the teaching profession.

More than likely, positive experiences have

influenced them to choose education as a

career path (Ginsburg & Newman, 1985).

According to Lortie (1975) students that

choose to become teachers in college, have

often had positive experiences associated with

education that dictate their beliefs about

teaching and schooling. Why would they

change their beliefs of teaching and schooling

if their own experiences were positive? Beliefs lead to perspective and ultimately guide

an educators approach to classroom teaching.

Consequently, most teachers beliefs do not

change dramatically in college. This leads to

practitioners entering a profession with beliefs

that hinder student progress and a system that

begs for change (Lortie 1975).

What are teacher education programs

doing to challenge these beliefs and produce

teachers that are willing to assist in reform?

When No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was

brought into effect, highly qualified teachers

were needed to implement the program and

produce results. The teachers had to meet the

following criteria: hold a bachelors degree,

demonstrate competence in their content area,

and possess a full state license (United States

Department of Education, 2004). Universities

have since attempted to enhance the rigor in

their preservice programs through methodology and content courses, but there is little evidence that these institutions produce teachers

that are culturally responsive, and can produce change in urban settings (Siwatu, 2007).

education programs may need to include the

examination of beliefs related to knowledge,

race, culture, teaching practices, teaching as a

profession, expectations of students, and social

relations within and beyond the classroom (p. 97).

References

Ginsburg, M. B., & Newman, K. K. (1985).

Social inequalities, schooling, and teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 36(2),

49-54.

Lortie, D. (1975). Schoolteacher: A sociological study. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago

Press.

Love, A., & Kruger, A. C. (2005). Teacher

beliefs and student achievement in urban

schools serving African American students.

The Journal of Educational Research, 99(2),

87-98.

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers beliefs and

educational research: Cleaning up a messy

construct. Review of Educational Research, 62

(3), 307-332.

Volume II, Issue 1

January 2016

Inside this Issue

Book Reviews:

Flat World Education

&

African Americans and

College Choice

Women in STEM

2016 International

Conference on Urban

Education in San Juan,

Puerto Rico

Good as Gold Staff

Dymilah Hewitt, Editor

Katie Brown, Assistant Editor

Tempestt Adams, Founder

Urban Educators for Change

2015-2016 Officers

Laura Handler, President

Delphia Smith, Treasurer

Amber Bryant, Secretary

Tiffany Hollis,

GPSG Representative

Why are so many beginning teachers

ill-prepared to work in urban settings and

what are teacher education programs lacking

in this regard? Love (2005) suggests teacher

Dr. Chance Lewis,

Faculty Advisor

Courtney Glavich is a doctoral student at UNCC.

Page 2

Volume , Issue

Good as Gold

Page 3

Book Review

African Americans and College Choice: The Influence of Family and School

by Kassie Freeman

Review written by Dymilah Hewitt

Students have a variety of options when it comes to

higher education, so they must accurately weigh their options

to ensure the best possible fit. Kassie Freemans African

Americans and College Choice: The Influence of Family and

School is a clearly written book that explores the factors that

impact the college selection process of African American

youth. A frican A mericans and College Choice was published

by State University of New York Press in 2005. Kassie Freeman has enjoyed a distinguished career in higher education.

She earned her Ph.D. in Educational Studies from Emory University and has held executive-level leadership positions at

Bowdoin College, Dillard University, Alcorn State University

and Southern University. The authors goal in writing this

book was to better understand the gap between the number of

African American youth that express the desire to earn a college degree, and the number who actually matriculate and

graduate from college. As she attempts to address this disparity, she examines the family, school and community factors that

influence college choice for African American youth.

African Americans and College Choice addresses the

impact of race, gender and social class on the type of college a

student selects or whether that student will attend college at all.

The specific institutions that the author calls into question are

the primary and secondary schools that the students attend, as

well as federally funded programs and local colleges. Each

entity has the potential to play a huge role in whether or not the

students receive the information and support that they need to

believe they are college material and make informed decisions

to adequately prepare them for college admission.

Freeman utilized a qualitative inquiry method. She

conducted 16 group interviews of African American high

school students, grades 10 through 12 from public and private

high schools in Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York and

Washington D.C. A total of 70 students (31 male and 39 female) were interviewed for the project from 16 different (inner

-city, magnet, and suburban) high schools. Freeman was particularly interested in learning how students plan their postsecondary futures. In the interview transcripts, students exposed

problems and provided potential solutions that could help students, parents, teachers, administrators and other stakeholders.

The interviews yielded a number of significant findings. Elementary school is the best time to begin encouraging

students to attend college. Students were very aware of when

they decided to go to college. She classified students in the

categories of knowers, seekers and dreamers with regard to

their intent to attend college. The participants had a variety of

reasons for choosing a historically black college or university

(HBCU) or a predominantly white institution (PWI). Students

chose HBCUs to get back to their cultural roots and to learn in

an environment where they would not be considered a

minority Many of them were convinced by a trusted mentor that an HBCU was the best option. Some of the students

who chose PWIs did so because they felt they needed exposure to whites and other cultures to prepare for the real

world.

According to the students, the barriers to African

Americans college matriculation fell into two broad categories: economic and psychological. The economic barriers

were the lack of funds to attend college or the lack of wellpaid job opportunities after graduating. The psychological

barriers were the internalization of the belief that college

was not an option, the loss of hope and the intimidation factor. From the interview data, Freeman found that some of

the actions that could increase African American participation in higher education were the improvement of the physical condition of primary and secondary schools; the recruitment of more committed teachers and counselors; and the

emphasis of cultural awareness in the curriculum.

In this book, the author refuses to blame African

American students and their parents. She argues that African Americans value education, but schools need dedicated

teachers who use culturally relevant pedagogy. They also

need principals who know how to create an atmosphere that

promotes the belief that all children can learn and go to college. While this book is ten years old, it is an excellent

study that covers many of the major themes in urban education. Freeman makes a concerted effort to reach African

American youth from a variety of different social classes

and educational backgrounds to provide meaningful results.

Her sample of students allows for some comparison along

gender and class lines. While the design of this study is very

focused in its scope, a good follow up would be the exploration of the college choices of nontraditional students.

Dymilah Hewitt is a doctoral student at UNCC.

Women in STEM: The Roots of the Disparities in Schools & the Workplace

By Katie Brown

References

Women are significantly underrepresented in STEM

(science, technology, engineering, and math) fields, both in

higher education and in the workforce. According to the

United States Department of Commerce, only 24% of jobs in

STEM were held by women as of 2009 (Beede et al., 2011).

Beede et al. (2011) attribute this disparity in part to a corresponding gender gap in STEM in higher education. In 2009,

6.7 million men in the American workforce held college degrees in STEM fields, while only 2.5 million American

women held the same degrees (Beede et al., 2011). According to EduCause, the U.S. is facing a growing skills gap in

STEM, wherein highly skilled jobs in STEM fields are going

unfilled or going to foreign workers due to a shortage of

qualified American workers to fill these positions (Evans,

McKenna, & Schulte, 2013). By increasing the number of

women entering STEM programs of study and ultimately

pursuing employment in STEM fields, educators can help to

close this skills gap, as well as help to close the gender gap in

STEM fields.

Beede, D., Julian, T., Langdon, D., McKittrick, G., Khan, B.,

& Doms, M. (2011). W omen in STEM: A gender gap to innovation. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. Retrieved from http://www.esa.doc.gov/

sites/default/files/ reports/documents/

womeninstemagaptoinnovation8311.pdf

The roots of this gender imbalance in STEM in

higher education can be found in a corresponding imbalance

in STEM education at the K-12 level. AP math and science

courses are dominated by boys; while more girls than boys

took AP tests in biology and environmental science in 2013,

male students outnumbered female students in calculus,

chemistry, computer science, and physics by as many as five

to one (College Board, 2013). Nationwide, only 21% of students participating in high school STEM programs were girls

(Office for Civil Rights, 2012).

Office for Civil Rights. (2012). Gender equity in education: A

data snapshot. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/

offices/list/ocr/docs/gender-equity-in-education.pdf

College Board. (2013). Program summary report. Retrieved

from http://media.collegeboard.com /digitalServices/pdf/

research/2013/Program-Summary-Report-2013.pdf

Evans, C., McKenna, M., & Schulte, B. (2013, June 3). Closing the gap: Addressing STEM workforce challenges. EDUCAUSE Review. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ero/

article/closing-gap-addressing-stem-workforce-challenges

Leaper, C., Farkas, T., & Brown, C. S. (2012). Adolescent

girls experiences and gender-related beliefs in relation to their

motivation in math/science and English. Journal of Youth and

Adolescence, 41(3), 268-282.

A combination of social and psychological factors

also contributes to low rates of female participation in

STEM. Beede et al. (2011) cite the lack of female role models in STEM fields as a contributing factor to this disparity.

Science and math have traditionally been gendered subjects,

where participation and achievement has been expected and

encouraged more from boys than from girls (Leaper, Farkas,

& Brown, 2012). This social expectation contributes to a

psychological phenomenon wherein many girls exhibit low

levels of self-efficacy in math and science, and do not think

of themselves as capable in these subjects (Leaper, Farkas, &

Brown, 2012). Thus, in order to bring more women into

STEM fields of study and professions in the future, we must

help girls envision themselves as scientists, mathematicians,

and engineers

Katie Brown is a doctoral candidate at UNCC.

You might also like

- What Is A College Culture Facilitating College PreDocument34 pagesWhat Is A College Culture Facilitating College PreJorge Prado CarvajalNo ratings yet

- NDU Elementary Training Department in The Context of New Normal EducationDocument41 pagesNDU Elementary Training Department in The Context of New Normal EducationFrancis Almonte Jr.No ratings yet

- Course SynthesisDocument13 pagesCourse Synthesisapi-599834281No ratings yet

- A Caring Errand 2: A Strategic Reading System for Content- Area Teachers and Future TeachersFrom EverandA Caring Errand 2: A Strategic Reading System for Content- Area Teachers and Future TeachersNo ratings yet

- Critical Issue in Higher EducationDocument7 pagesCritical Issue in Higher Educationapi-438185399No ratings yet

- IJCRT2302234Document6 pagesIJCRT2302234haysgab925No ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument2 pagesReview of Related Literature and StudiesNoldlin Dimaculangan73% (79)

- School Counselors As Social Capital-Effects of High School College Counseling - BRYAN ET AL 2011Document11 pagesSchool Counselors As Social Capital-Effects of High School College Counseling - BRYAN ET AL 2011Adrian GallegosNo ratings yet

- Developing A Cross-Cultural Approach To School Leadership - AASA - February 17-20, 2005Document19 pagesDeveloping A Cross-Cultural Approach To School Leadership - AASA - February 17-20, 2005pberkowitz100% (1)

- Claudia Hui - Directed StudyDocument8 pagesClaudia Hui - Directed Studyapi-456354229No ratings yet

- Lideres Educativos PDFDocument21 pagesLideres Educativos PDFMUSICA BILLNo ratings yet

- Ej1162276 PDFDocument17 pagesEj1162276 PDFloklkioNo ratings yet

- EJ1162276Document17 pagesEJ1162276El AdamNo ratings yet

- Em PHD Spring Newsletter - TownsendDocument2 pagesEm PHD Spring Newsletter - Townsendapi-315368788No ratings yet

- Syllabus - Eed FinalDocument9 pagesSyllabus - Eed Finalapi-301873872No ratings yet

- DiversitywordDocument13 pagesDiversitywordapi-336844438No ratings yet

- Diploma Matters: A Field Guide for College and Career ReadinessFrom EverandDiploma Matters: A Field Guide for College and Career ReadinessNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Realizations of First Generation Students Who Navigated Through Transfer Momentum PointsDocument16 pagesChallenges and Realizations of First Generation Students Who Navigated Through Transfer Momentum PointsZrhyNo ratings yet

- Walk in The Light Dew Drops of Student Activism AgencyDocument18 pagesWalk in The Light Dew Drops of Student Activism Agencyapi-385542384No ratings yet

- Thejourneytograduateschool PaperDocument12 pagesThejourneytograduateschool Paperapi-255001706No ratings yet

- Ab Gardeakoral FinalDocument10 pagesAb Gardeakoral Finalapi-439300794No ratings yet

- Ackers Scholars Programs StudyDocument11 pagesAckers Scholars Programs Studyapi-317321425No ratings yet

- Teacher Education across Minority-Serving Institutions: Programs, Policies, and Social JusticeFrom EverandTeacher Education across Minority-Serving Institutions: Programs, Policies, and Social JusticeNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Character Education On Positive Behavior in TheDocument37 pagesThe Influence of Character Education On Positive Behavior in TheErwin Y. CabaronNo ratings yet

- Thejourneytograduateschool PaperDocument12 pagesThejourneytograduateschool Paperapi-239817112No ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document11 pagesChapter 2Elyssa ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Divergent Paths to College: Race, Class, and Inequality in High SchoolsFrom EverandDivergent Paths to College: Race, Class, and Inequality in High SchoolsNo ratings yet

- Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement ThesisDocument7 pagesSocioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement Thesisgbtrjrap100% (1)

- Hb-Eop Student Adjustment To CampusDocument12 pagesHb-Eop Student Adjustment To Campusapi-302067836No ratings yet

- Power and Education explores Critical Spiritual PedagogyDocument15 pagesPower and Education explores Critical Spiritual PedagogyjenifercrawfordNo ratings yet

- Field Experience ReflectionDocument8 pagesField Experience Reflectionapi-283603339No ratings yet

- William Allan Kritsonis, PHDDocument5 pagesWilliam Allan Kritsonis, PHDWilliam Allan Kritsonis, PhDNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Importance of EducationDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Importance of Educationfzg6pcqd100% (1)

- AnnotatedbibliographyDocument6 pagesAnnotatedbibliographyapi-296680437No ratings yet

- Commuter Students Literature ReviewDocument13 pagesCommuter Students Literature Reviewapi-414897560100% (1)

- The Fixed Pipeline Understanding and Reforming The Advanced Education SystemDocument25 pagesThe Fixed Pipeline Understanding and Reforming The Advanced Education SystemDanielNo ratings yet

- Reasearch Based Decision MakingDocument2 pagesReasearch Based Decision Makingapi-637060712No ratings yet

- Ethnic Studies With K - 12 Students, Families, and Communities: The Role of Teacher Education in Preparing Educators To Serve The PeopleDocument15 pagesEthnic Studies With K - 12 Students, Families, and Communities: The Role of Teacher Education in Preparing Educators To Serve The PeopleMaria SantanaNo ratings yet

- Peer Group Influence and Academic Aspirations Across CulturalDocument9 pagesPeer Group Influence and Academic Aspirations Across CulturalAloy Son MlawaNo ratings yet

- First-Generation College Students PaperDocument80 pagesFirst-Generation College Students Paperapi-404386449No ratings yet

- Prisoners or Presidents: The Simple Things That Change Everything; When Principals Lead Like Lives Depend on ItFrom EverandPrisoners or Presidents: The Simple Things That Change Everything; When Principals Lead Like Lives Depend on ItNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 723883Document35 pagesNi Hms 723883ArthurNo ratings yet

- Mixed Methods ExemplarsDocument26 pagesMixed Methods ExemplarsTasminNo ratings yet

- Final Paper 1Document18 pagesFinal Paper 1api-356381134No ratings yet

- Cche 680 Learning Unit 1Document11 pagesCche 680 Learning Unit 1api-314103428No ratings yet

- Collaborative Action Research To Implement Social-Emotional LearnDocument23 pagesCollaborative Action Research To Implement Social-Emotional LearnAirene GraceNo ratings yet

- Soc Ofhighered FinalpaperDocument15 pagesSoc Ofhighered Finalpaperapi-300973520No ratings yet

- Annotated MDocument14 pagesAnnotated Mapi-667786364No ratings yet

- OnesizefitsalleducationDocument13 pagesOnesizefitsalleducationapi-309799896No ratings yet

- Research SY 2023 2024Document19 pagesResearch SY 2023 2024charlesferrer718No ratings yet

- Synthesis PaperDocument17 pagesSynthesis Paperapi-511635668No ratings yet

- Ethics and Higher Education Synthesis PaperDocument6 pagesEthics and Higher Education Synthesis Paperapi-549170994No ratings yet

- Curriculum and Instruction: Selections from Research to Guide Practice in Middle Grades EducationFrom EverandCurriculum and Instruction: Selections from Research to Guide Practice in Middle Grades EducationNo ratings yet

- Teacher perceptions of school uniforms and climateDocument10 pagesTeacher perceptions of school uniforms and climateennyNo ratings yet

- Critical Pedagogy For EducatorDocument113 pagesCritical Pedagogy For EducatorMazaya Conita WidaputriNo ratings yet

- Reimagining After-School Symposium SummaryDocument12 pagesReimagining After-School Symposium SummarycitizenschoolsNo ratings yet

- The Overrepresentation of African Americans in Special EducationDocument7 pagesThe Overrepresentation of African Americans in Special Educationapi-302691707No ratings yet

- Woodson Final Research ProposalDocument31 pagesWoodson Final Research Proposalapi-347583078No ratings yet

- Classroom Biases Hinder Students' Learning: Sarah D. SparksDocument4 pagesClassroom Biases Hinder Students' Learning: Sarah D. Sparksapi-277057088No ratings yet

- Ka4e BrownDocument1 pageKa4e Brownapi-277057088No ratings yet

- Kaie'S Summer Work Plan: Drad To Defense: May June July AugustDocument1 pageKaie'S Summer Work Plan: Drad To Defense: May June July Augustapi-277057088No ratings yet

- National Longitudinal Study Criminal-Justice and School Sanctions Against Nonheterosexual Youth: ADocument11 pagesNational Longitudinal Study Criminal-Justice and School Sanctions Against Nonheterosexual Youth: Aapi-277057088No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledapi-277057088No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledapi-277057088No ratings yet

- Journal of Homosexuality: To Cite This Article: Karma R. Chávez PHD (2011) Identifying The Needs of LGBTQ ImmigrantsDocument31 pagesJournal of Homosexuality: To Cite This Article: Karma R. Chávez PHD (2011) Identifying The Needs of LGBTQ Immigrantsapi-277057088No ratings yet

- LGBTQ Youth of Color:: Discipline Disparities, School Push-Out, and The School-to-Prison PipelineDocument16 pagesLGBTQ Youth of Color:: Discipline Disparities, School Push-Out, and The School-to-Prison Pipelineapi-277057088No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledapi-277057088No ratings yet

- OCFINALEXAM2019Document6 pagesOCFINALEXAM2019DA FT100% (1)

- CPB145 CVTDocument1 pageCPB145 CVTDantiancNo ratings yet

- 28 Nakshatras - The Real Secrets of Vedic Astrology (An E-Book)Document44 pages28 Nakshatras - The Real Secrets of Vedic Astrology (An E-Book)Karthik Balasundaram88% (8)

- Munslow, A. What History IsDocument2 pagesMunslow, A. What History IsGoshai DaianNo ratings yet

- TNT Construction PLC - Tender 3Document42 pagesTNT Construction PLC - Tender 3berekajimma100% (1)

- Find Bridges in a Graph Using DFSDocument15 pagesFind Bridges in a Graph Using DFSVamshi YadavNo ratings yet

- Facebook Use Case Diagram Activity Diagram Sequence DiagramDocument21 pagesFacebook Use Case Diagram Activity Diagram Sequence DiagramSaiNo ratings yet

- St. Helen Church: 4106 Mountain St. Beamsville, ON L0R 1B7Document5 pagesSt. Helen Church: 4106 Mountain St. Beamsville, ON L0R 1B7sthelenscatholicNo ratings yet

- Old Testament Books Bingo CardsDocument9 pagesOld Testament Books Bingo CardsSiagona LeblancNo ratings yet

- Assignment No1 of System Analysis and Design: Submitted To Submitted byDocument7 pagesAssignment No1 of System Analysis and Design: Submitted To Submitted byAnkur SinghNo ratings yet

- EN4264 Final Essay - GeraldineDocument25 pagesEN4264 Final Essay - GeraldineGeraldine WongNo ratings yet

- Failure CountersDocument28 pagesFailure CountersБотирали АзибаевNo ratings yet

- Facebook Privacy FTC Complaint Docket No. C-4365Document19 pagesFacebook Privacy FTC Complaint Docket No. C-4365David SangerNo ratings yet

- Unit 20: Where Is Sapa: 2.look, Read and CompleteDocument4 pagesUnit 20: Where Is Sapa: 2.look, Read and CompleteNguyenThuyDungNo ratings yet

- Clinical Skills Resource HandbookDocument89 pagesClinical Skills Resource Handbookanggita budi wahyono100% (1)

- Rational design of Nile bargesDocument8 pagesRational design of Nile bargesjhairNo ratings yet

- Focus2 2E Review Test 4 Units1 8 Vocabulary Grammar UoE Reading GroupBDocument4 pagesFocus2 2E Review Test 4 Units1 8 Vocabulary Grammar UoE Reading GroupBaides1sonNo ratings yet

- June 1997 North American Native Orchid JournalDocument117 pagesJune 1997 North American Native Orchid JournalNorth American Native Orchid JournalNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Management Plan Case Study 1Document2 pagesStakeholder Management Plan Case Study 1Krister VallenteNo ratings yet

- FCC TechDocument13 pagesFCC TechNguyen Thanh XuanNo ratings yet

- Best Practices in Implementing A Secure Microservices ArchitectureDocument85 pagesBest Practices in Implementing A Secure Microservices Architecturewenapo100% (1)

- The Sociopath's MantraDocument2 pagesThe Sociopath's MantraStrategic ThinkerNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Perception of Selected High School Students With Regards To Sex Education and Its ContentDocument4 pagesKnowledge and Perception of Selected High School Students With Regards To Sex Education and Its ContentJeffren P. Miguel0% (1)

- Gallbladder Removal Recovery GuideDocument14 pagesGallbladder Removal Recovery GuideMarin HarabagiuNo ratings yet

- PPT ch01Document45 pagesPPT ch01Junel VeriNo ratings yet

- Tarea 1Document36 pagesTarea 1LUIS RVNo ratings yet

- B1 Grammar and VocabularyDocument224 pagesB1 Grammar and VocabularyTranhylapNo ratings yet

- Choi, J H - Augustinian Interiority-The Teleological Deification of The Soul Through Divine Grace PDFDocument253 pagesChoi, J H - Augustinian Interiority-The Teleological Deification of The Soul Through Divine Grace PDFed_colenNo ratings yet

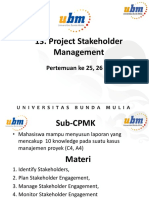

- PB13MAT - 13 Project Stakeholder ManagementDocument30 pagesPB13MAT - 13 Project Stakeholder ManagementYudhi ChristianNo ratings yet

- 2023 Civil LawDocument7 pages2023 Civil LawJude OnrubiaNo ratings yet