Professional Documents

Culture Documents

En Banc: Franklin S. Farolan For Petitioner Kapatiran in G.R. No. 81311

Uploaded by

RavenFoxOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

En Banc: Franklin S. Farolan For Petitioner Kapatiran in G.R. No. 81311

Uploaded by

RavenFoxCopyright:

Available Formats

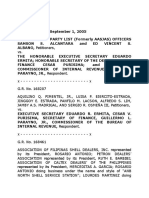

EN BANC

G.R. No. 81311 June 30, 1988

KAPATIRAN NG MGA NAGLILINGKOD SA PAMAHALAAN NG

PILIPINAS, INC., HERMINIGILDO C. DUMLAO, GERONIMO

Q. QUADRA, and MARIO C. VILLANUEVA, petitioners,

vs.

HON. BIENVENIDO TAN, as Commissioner of Internal

Revenue, respondent.

G.R. No. 81820 June 30, 1988

KILUSANG MAYO UNO LABOR CENTER (KMU), its officers

and affiliated labor federations and alliances, petitioners,

vs.

THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY, SECRETARY OF FINANCE, THE

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, and SECRETARY

OF BUDGET, respondents.

G.R. No. 81921 June 30, 1988

INTEGRATED CUSTOMS BROKERS ASSOCIATION OF THE

PHILIPPINES

and

JESUS

B.

BANAL, petitioners,

vs.

The HON. COMMISSIONER, BUREAU OF INTERNAL

REVENUE, respondent.

G.R. No. 82152 June 30, 1988

RICARDO

C.

VALMONTE, petitioner,

vs.

THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY, SECRETARY OF FINANCE,

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE and SECRETARY

OF BUDGET, respondent.

Franklin S. Farolan for petitioner Kapatiran in G.R. No. 81311.

Jaime C. Opinion for individual petitioners in G.R. No. 81311.

Banzuela, Flores, Miralles, Raeses, Sy, Taquio and Associates for

petitioners in G.R. No 81820.

Union of Lawyers and Advocates for Peoples Right collaborating

counsel for petitioners in G.R. No 81820.

Jose C. Leabres and Joselito R. Enriquez for petitioners in G.R.

No. 81921.

PADILLA, J.:

These four (4) petitions, which have been consolidated because of

the similarity of the main issues involved therein, seek to nullify

Executive Order No. 273 (EO 273, for short), issued by the

President of the Philippines on 25 July 1987, to take effect on 1

January 1988, and which amended certain sections of the

National Internal Revenue Code and adopted the value-added tax

(VAT, for short), for being unconstitutional in that its enactment is

not alledgedly within the powers of the President; that the VAT is

oppressive, discriminatory, regressive, and violates the due

process and equal protection clauses and other provisions of the

1987 Constitution.

The Solicitor General prays for the dismissal of the petitions on

the ground that the petitioners have failed to show justification

for the exercise of its judicial powers, viz. (1) the existence of an

appropriate case; (2) an interest, personal and substantial, of the

party raising the constitutional questions; (3) the constitutional

question should be raised at the earliest opportunity; and (4) the

question of constitutionality is directly and necessarily involved in

a justiciable controversy and its resolution is essential to the

protection of the rights of the parties. According to the Solicitor

General, only the third requisite that the constitutional

question should be raised at the earliest opportunity has been

complied with. He also questions the legal standing of the

petitioners who, he contends, are merely asking for an advisory

opinion from the Court, there being no justiciable controversy for

resolution.

Objections to taxpayers' suit for lack of sufficient personality

standing, or interest are, however, in the main procedural

matters. Considering the importance to the public of the cases at

bar, and in keeping with the Court's duty, under the 1987

Constitution, to determine wether or not the other branches of

government have kept themselves within the limits of the

Constitution and the laws and that they have not abused the

discretion given to them, the Court has brushed aside

technicalities of procedure and has taken cognizance of these

petitions.

But, before resolving the issues raised, a brief look into the tax

law in question is in order.

The VAT is a tax levied on a wide range of goods and services. It

is a tax on the value, added by every seller, with aggregate gross

annual sales of articles and/or services, exceeding P200,00.00, to

his purchase of goods and services, unless exempt. VAT is

computed at the rate of 0% or 10% of the gross selling price of

goods or gross receipts realized from the sale of services.

The VAT is said to have eliminated privilege taxes, multiple rated

sales tax on manufacturers and producers, advance sales tax,

and compensating tax on importations. The framers of EO 273

that it is principally aimed to rationalize the system of taxing

goods and services; simplify tax administration; and make the

tax system more equitable, to enable the country to attain

economic recovery.

The VAT is not entirely new. It was already in force, in a modified

form, before EO 273 was issued. As pointed out by the Solicitor

General, the Philippine sales tax system, prior to the issuance of

EO 273, was essentially a single stage value added tax system

computed under the "cost subtraction method" or "cost deduction

method" and was imposed only on original sale, barter or

exchange of articles by manufacturers, producers, or importers.

Subsequent sales of such articles were not subject to sales tax.

However, with the issuance of PD 1991 on 31 October 1985, a 3%

tax was imposed on a second sale, which was reduced to 1.5%

upon the issuance of PD 2006 on 31 December 1985, to take

effect 1 January 1986. Reduced sales taxes were imposed not

only on the second sale, but on everysubsequent sale, as well. EO

273 merely increased the VAT on every sale to 10%, unless zerorated or exempt.

Petitioners first contend that EO 273 is unconstitutional on the

Ground that the President had no authority to issue EO 273 on 25

July 1987.

The contention is without merit.

It should be recalled that under Proclamation No. 3, which

decreed a Provisional Constitution, sole legislative authority was

vested upon the President. Art. II, sec. 1 of the Provisional

Constitution states:

Sec. 1. Until a legislature is elected and convened

under a new Constitution, the President shall continue

to exercise legislative powers.

On 15 October 1986, the Constitutional Commission of 1986

adopted a new Constitution for the Republic of the Philippines

which was ratified in a plebiscite conducted on 2 February 1987.

Article XVIII, sec. 6 of said Constitution, hereafter referred to as

the 1987 Constitution, provides:

Sec. 6. The incumbent President shall continue to

exercise legislative powers until the first Congress is

convened.

It should be noted that, under both the Provisional and the 1987

Constitutions, the President is vested with legislative powers until

a legislature under a new Constitution is convened. The first

Congress, created and elected under the 1987 Constitution, was

convened on 27 July 1987. Hence, the enactment of EO 273 on

25 July 1987, two (2) days before Congress convened on 27 July

1987, was within the President's constitutional power and

authority to legislate.

Petitioner Valmonte claims, additionally, that Congress was really

convened on 30 June 1987 (not 27 July 1987). He contends that

the word "convene" is synonymous with "the date when the

elected members of Congress assumed office."

The contention is without merit. The word "convene" which has

been interpreted to mean "to call together, cause to assemble, or

convoke," 1 is clearly different from assumption of office by

the individual members of Congress or their taking the oath of

office. As an example, we call to mind the interim National

Assembly created under the 1973 Constitution, which had not

been "convened" but some members of the body, more

particularly the delegates to the 1971 Constitutional Convention

who had opted to serve therein by voting affirmatively for the

approval of said Constitution, had taken their oath of office.

To uphold the submission of petitioner Valmonte would stretch the

definition of the word "convene" a bit too far. It would also defeat

the purpose of the framers of the 1987 Constitutional and render

meaningless some other provisions of said Constitution. For

example, the provisions of Art. VI, sec. 15, requiring Congress

to convene once every year on the fourth Monday of July for its

regular session would be a contrariety, since Congress would

already be deemed to be in session after the individual members

have taken their oath of office. A portion of the provisions of Art.

VII, sec. 10, requiring Congress to convene for the purpose of

enacting a law calling for a special election to elect a President

and Vice-President in case a vacancy occurs in said offices, would

also be a surplusage. The portion of Art. VII, sec. 11, third

paragraph, requiring Congress to convene, if not in session, to

decide a conflict between the President and the Cabinet as to

whether or not the President and the Cabinet as to whether or

not the President can re-assume the powers and duties of his

office, would also be redundant. The same is true with the portion

of Art. VII, sec. 18, which requires Congress to convene within

twenty-four (24) hours following the declaration of martial law or

the suspension of the privilage of the writ of habeas corpus.

The 1987 Constitution mentions a specific date when the

President loses her power to legislate. If the framers of said

Constitution had intended to terminate the exercise of legislative

powers by the President at the beginning of the term of office of

the members of Congress, they should have so stated (but did

not) in clear and unequivocal terms. The Court has not power to

re-write the Constitution and give it a meaning different from that

intended.

The Court also finds no merit in the petitioners' claim that EO 273

was issued by the President in grave abuse of discretion

amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction. "Grave abuse of

discretion" has been defined, as follows:

Grave abuse of discretion" implies such capricious and

whimsical exercise of judgment as is equivalent to lack

of jurisdiction (Abad Santos vs. Province of Tarlac, 38

Off. Gaz. 834), or, in other words, where the power is

exercised in an arbitrary or despotic manner by reason

of passion or personal hostility, and it must be so

patent and gross as to amount to an evasion of positive

duty or to a virtual refusal to perform the duty enjoined

or to act at all in contemplation of law. (Tavera-Luna,

Inc. vs. Nable, 38 Off. Gaz. 62). 2

Petitioners have failed to show that EO 273 was issued

capriciously and whimsically or in an arbitrary or despotic manner

by reason of passion or personal hostility. It appears that a

comprehensive study of the VAT had been extensively discussed

by this framers and other government agencies involved in its

implementation, even under the past administration. As the

Solicitor General correctly sated. "The signing of E.O. 273 was

merely the last stage in the exercise of her legislative powers.

The legislative process started long before the signing when the

data were gathered, proposals were weighed and the final

wordings of the measure were drafted, revised and finalized.

Certainly, it cannot be said that the President made a jump, so to

speak, on the Congress, two days before it convened." 3

Next, the petitioners claim that EO 273 is oppressive,

discriminatory, unjust and regressive, in violation of the

provisions of Art. VI, sec. 28(1) of the 1987 Constitution, which

states:

Sec. 28 (1) The rule of taxation shall be uniform and

equitable. The Congress shall evolve a progressive

system of taxation.

The petitioners" assertions in this regard are not supported by

facts and circumstances to warrant their conclusions. They have

failed to adequately show that the VAT is oppressive,

discriminatory or unjust. Petitioners merely rely upon newspaper

articles which are actually hearsay and have evidentiary value. To

justify the nullification of a law. there must be a clear and

unequivocal breach of the Constitution, not a doubtful and

argumentative implication. 4

As the Court sees it, EO 273 satisfies all the requirements of a

valid tax. It is uniform. The court, in City of Baguio vs. De

Leon, 5 said:

... In Philippine Trust Company v. Yatco (69 Phil. 420),

Justice Laurel, speaking for the Court, stated: "A tax is

considered uniform when it operates with the same

force and effect in every place where the subject may

be found."

There was no occasion in that case to consider the

possible effect on such a constitutional requirement

where there is a classification. The opportunity came in

Eastern Theatrical Co. v. Alfonso (83 Phil. 852, 862).

Thus: "Equality and uniformity in taxation means that

all taxable articles or kinds of property of the same

class shall be taxed at the same rate. The taxing power

has the authority to make reasonable and natural

classifications for purposes of taxation; . . ." About two

years later, Justice Tuason, speaking for this Court in

Manila Race Horses Trainers Assn. v. de la Fuente (88

Phil. 60, 65) incorporated the above excerpt in his

opinion and continued; "Taking everything into account,

the differentiation against which the plaintiffs complain

conforms to the practical dictates of justice and equity

and is not discriminatory within the meaning of the

Constitution."

To satisfy this requirement then, all that is needed as

held in another case decided two years later, (Uy Matias

v. City of Cebu, 93 Phil. 300) is that the statute or

ordinance in question "applies equally to all persons,

firms and corporations placed in similar situation." This

Court is on record as accepting the view in a leading

American case (Carmichael v. Southern Coal and Coke

Co., 301 US 495) that "inequalities which result from a

singling out of one particular class for taxation or

exemption infringe no constitutional limitation." (Lutz v.

Araneta, 98 Phil. 148, 153).

The sales tax adopted in EO 273 is applied similarly on all goods

and services sold to the public, which are not exempt, at the

constant rate of 0% or 10%.

The disputed sales tax is also equitable. It is imposed only on

sales of goods or services by persons engage in business with an

aggregate gross annual sales exceeding P200,000.00. Small

corner sari-sari stores are consequently exempt from its

application. Likewise exempt from the tax are sales of farm and

marine products, spared as they are from the incidence of the

VAT, are expected to be relatively lower and within the reach of

the general public. 6

The Court likewise finds no merit in the contention of the

petitioner Integrated Customs Brokers Association of the

Philippines that EO 273, more particularly the new Sec. 103 (r) of

the National Internal Revenue Code, unduly discriminates against

customs brokers. The contested provision states:

Sec. 103. Exempt transactions. The following shall

be exempt from the value-added tax:

xxx xxx xxx

(r) Service performed in the exercise of profession or

calling (except customs brokers) subject to the

occupation tax under the Local Tax Code, and

professional services performed by registered general

professional partnerships;

The phrase "except customs brokers" is not meant to discriminate

against customs brokers. It was inserted in Sec. 103(r) to

complement the provisions of Sec. 102 of the Code, which makes

the services of customs brokers subject to the payment of the

VAT and to distinguish customs brokers from other professionals

who are subject to the payment of an occupation tax under the

Local Tax Code. Pertinent provisions of Sec. 102 read:

Sec. 102. Value-added tax on sale of services. There

shall be levied, assessed and collected, a value-added

tax equivalent to 10% percent of gross receipts derived

by any person engaged in the sale of services. The

phrase sale of services" means the performance of all

kinds of services for others for a fee, remuneration or

consideration, including those performed or rendered

by construction and service contractors; stock, real

estate, commercial, customs and immigration brokers;

lessors of personal property; lessors or distributors of

cinematographic films; persons engaged in milling,

processing, manufacturing or repacking goods for

others; and similar services regardless of whether or

not the performance thereof call for the exercise or use

of the physical or mental faculties: ...

With the insertion of the clarificatory phrase "except customs

brokers" in Sec. 103(r), a potential conflict between the two

sections, (Secs. 102 and 103), insofar as customs brokers are

concerned, is averted.

At any rate, the distinction of the customs brokers from the other

professionals who are subject to occupation tax under the Local

Tax Code is based upon material differences, in that the activities

of customs brokers (like those of stock, real estate and

immigration brokers) partake more of a business, rather than a

profession and were thus subjected to the percentage tax under

Sec. 174 of the National Internal Revenue Code prior to its

amendment by EO 273. EO 273 abolished the percentage tax and

replaced it with the VAT. If the petitioner Association did not

protest the classification of customs brokers then, the Court sees

no reason why it should protest now.

The Court takes note that EO 273 has been in effect for more

than five (5) months now, so that the fears expressed by the

petitioners that the adoption of the VAT will trigger skyrocketing

of prices of basic commodities and services, as well as mass

actions and demonstrations against the VAT should by now be

evident. The fact that nothing of the sort has happened shows

that the fears and apprehensions of the petitioners appear to be

more imagined than real. It would seem that the VAT is not as

bad as we are made to believe.

In any event, if petitioners seriously believe that the adoption and

continued application of the VAT are prejudicial to the general

welfare or the interests of the majority of the people, they should

seek recourse and relief from the political branches of the

government. The Court, following the time-honored doctrine of

separation of powers, cannot substitute its judgment for that of

the President as to the wisdom, justice and advisability of the

adoption of the VAT. The Court can only look into and determine

whether or not EO 273 was enacted and made effective as law, in

the manner required by, and consistent with, the Constitution,

and to make sure that it was not issued in grave abuse of

discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction; and, in this

regard, the Court finds no reason to impede its application or

continued implementation.

WHEREFORE,

the

petitions

pronouncement as to costs.

are

DISMISSED.

Without

You might also like

- Kapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan vs. TanDocument5 pagesKapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan vs. Tanabigael bobisNo ratings yet

- Kapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan NG Pilipinas, Inc vs. TanDocument6 pagesKapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan NG Pilipinas, Inc vs. TanLeBron DurantNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court upholds constitutionality of VAT under EO 273Document43 pagesSupreme Court upholds constitutionality of VAT under EO 273pulithepogiNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court upholds VAT under EO 273Document18 pagesSupreme Court upholds VAT under EO 273Aya AntonioNo ratings yet

- VAT Taxation Cases SummaryDocument86 pagesVAT Taxation Cases SummaryRose AnnNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Upholds VAT under EO 273Document5 pagesSupreme Court Upholds VAT under EO 273Rene ValentosNo ratings yet

- Kapatiran Vs TanDocument10 pagesKapatiran Vs TanAbs PangaderNo ratings yet

- Princ of Taxation Taxrev Regala IncDocument25 pagesPrinc of Taxation Taxrev Regala Incsamjuan1234No ratings yet

- KAPATIRAN NG MGA NAGLILINGKOD ETC. ET AL.20160322-9941-1b9hxiv PDFDocument7 pagesKAPATIRAN NG MGA NAGLILINGKOD ETC. ET AL.20160322-9941-1b9hxiv PDFRolan Villa del ReyNo ratings yet

- Kapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan VsDocument5 pagesKapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan VsammeNo ratings yet

- 1.) KAPATIRAN NG MGA NAGLILINGKOD SA PAMAHALAAN NG PILIPINAS, INC., HERMINIGILDO C. DUMLAO, GERONIMO Q. QUADRA, and MARIO C. VILLANUEVA v. HON. BIENVENIDO TAN G.R. No. 81311G.R. No. 81311Document5 pages1.) KAPATIRAN NG MGA NAGLILINGKOD SA PAMAHALAAN NG PILIPINAS, INC., HERMINIGILDO C. DUMLAO, GERONIMO Q. QUADRA, and MARIO C. VILLANUEVA v. HON. BIENVENIDO TAN G.R. No. 81311G.R. No. 81311Mae TrabajoNo ratings yet

- Kapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan NG Pilipinas, Inc. vs. Tan, 163 SCRA 371 (1988)Document16 pagesKapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan NG Pilipinas, Inc. vs. Tan, 163 SCRA 371 (1988)Jillian BatacNo ratings yet

- Taxation 2 Vat Case DigestsDocument27 pagesTaxation 2 Vat Case DigestsErnest MancenidoNo ratings yet

- Abakada Guro Party List Vs Executive SecretaryDocument8 pagesAbakada Guro Party List Vs Executive SecretaryshelNo ratings yet

- Abakada Guro Party List Vs Executive SecretaryDocument8 pagesAbakada Guro Party List Vs Executive SecretaryAndrea TiuNo ratings yet

- Tolentino vs. Secretary of Finance (1995)Document25 pagesTolentino vs. Secretary of Finance (1995)Phulagyn CañedoNo ratings yet

- Case Digest For Stat ConDocument10 pagesCase Digest For Stat Concarl fuerzasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14, 20, 21Document84 pagesChapter 14, 20, 21Warly PabloNo ratings yet

- Kapatiran Vs TanDocument3 pagesKapatiran Vs TanPoks Bongat AlejoNo ratings yet

- I.6 Kapatiran Vs Tan GR No. 81311 06301988 PDFDocument4 pagesI.6 Kapatiran Vs Tan GR No. 81311 06301988 PDFbabyclaire17No ratings yet

- Abakada Guro vs Ermita VAT caseDocument29 pagesAbakada Guro vs Ermita VAT caseMario P. Trinidad Jr.100% (2)

- Supreme Court upholds constitutionality of VAT Reform ActDocument11 pagesSupreme Court upholds constitutionality of VAT Reform ActNathaniel CaliliwNo ratings yet

- Stat ConDocument6 pagesStat ConRogelio A.C Jr.No ratings yet

- Abakada Guro Party List V Purisima G.R. NO. 166715, AUGUST 14, 2008 FactsDocument5 pagesAbakada Guro Party List V Purisima G.R. NO. 166715, AUGUST 14, 2008 FactsPatatas SayoteNo ratings yet

- Tañada vs. Tuvera Ruling on Presidential Decree PublicationDocument7 pagesTañada vs. Tuvera Ruling on Presidential Decree PublicationCyd D. BarrettoNo ratings yet

- ABAKADA Guro Party List Vs Executive SecretaryDocument3 pagesABAKADA Guro Party List Vs Executive SecretaryJulian Duba0% (1)

- Tan Vs ComelecDocument7 pagesTan Vs ComelecnchlrysNo ratings yet

- Kapatiran Vs TanDocument3 pagesKapatiran Vs TanWinnie Ann Daquil LomosadNo ratings yet

- Guingona vs. CaragueDocument3 pagesGuingona vs. CaragueClavel TuasonNo ratings yet

- Manila Prince Hotel Vs GsisDocument8 pagesManila Prince Hotel Vs GsisGrace Lacia Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Philconsa vs Gimenez ruling on constitutionality of retirement lawDocument20 pagesPhilconsa vs Gimenez ruling on constitutionality of retirement lawAaron ReyesNo ratings yet

- Court upholds constitutionality of VAT lawDocument16 pagesCourt upholds constitutionality of VAT lawGwen Alistaer CanaleNo ratings yet

- Tolentino V Sec of Finance DigestsDocument5 pagesTolentino V Sec of Finance DigestsDeb Bie100% (8)

- Constitutionality of Automatic Appropriations for Debt ServiceDocument4 pagesConstitutionality of Automatic Appropriations for Debt ServicePatronus GoldenNo ratings yet

- 6.1 Separation of PowersDocument16 pages6.1 Separation of PowersAlmazan RockyNo ratings yet

- Guingona V CaragueDocument4 pagesGuingona V CaragueAngela Marie AlmalbisNo ratings yet

- 38 - Kapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan NG PilipinasDocument2 pages38 - Kapatiran NG Mga Naglilingkod Sa Pamahalaan NG PilipinasAmity Rose RiveroNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules on Integration of Philippine Bar and Practice of Professions by Local OfficialsDocument6 pagesSupreme Court Rules on Integration of Philippine Bar and Practice of Professions by Local OfficialsreireiNo ratings yet

- Abacada Guro Vs ErmitaDocument10 pagesAbacada Guro Vs ErmitaPJr MilleteNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 71977 February 27, 1987 Demetrio G. Demetria, vs. Hon. Manuel Alba in His Capacity As The Minister of The BUDGET, RespondentsDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 71977 February 27, 1987 Demetrio G. Demetria, vs. Hon. Manuel Alba in His Capacity As The Minister of The BUDGET, RespondentsMaricar Corina CanayaNo ratings yet

- Constitutionality of Revised VAT LawDocument3 pagesConstitutionality of Revised VAT LawGM Alfonso100% (1)

- Kapatiran v. TanDocument3 pagesKapatiran v. TanfinserglenNo ratings yet

- Political Law ReviewerDocument51 pagesPolitical Law ReviewerApril Rose Flores FloresNo ratings yet

- Taxation of judicial salariesDocument2 pagesTaxation of judicial salariesAnonymous HH3c17osNo ratings yet

- Statcon DigestssssDocument17 pagesStatcon DigestssssDanielNo ratings yet

- Tolentino vs. Sec. of FInanceDocument3 pagesTolentino vs. Sec. of FInanceRaineir PabiranNo ratings yet

- Briones, Angenica Ellyse P.: Enhancement Activity/Outcome: A. Discuss/Explain The Following Terms and ConceptsDocument6 pagesBriones, Angenica Ellyse P.: Enhancement Activity/Outcome: A. Discuss/Explain The Following Terms and Conceptsangenica ellyse brionesNo ratings yet

- Case SummaryDocument6 pagesCase SummaryOdessa Ebol Alpay - QuinalayoNo ratings yet

- Mandanas V OchoaDocument54 pagesMandanas V OchoaGertrude ArquilloNo ratings yet

- Consti - Abakada vs. Executive - 469 SCRA 1 (2005)Document9 pagesConsti - Abakada vs. Executive - 469 SCRA 1 (2005)mheeyadulce100% (1)

- Abakada Group Party List VsDocument7 pagesAbakada Group Party List VsHarhar HereraNo ratings yet

- Court upholds constitutionality of VAT Reform ActDocument8 pagesCourt upholds constitutionality of VAT Reform ActKaizer ChanNo ratings yet

- 151185-1950-Perfecto v. Meer PDFDocument15 pages151185-1950-Perfecto v. Meer PDFCharmaine GraceNo ratings yet

- Assoc of Phil Dessicators Vs Phil Coconut AuthorityDocument7 pagesAssoc of Phil Dessicators Vs Phil Coconut AuthorityColleen Fretzie Laguardia NavarroNo ratings yet

- Poli Digested CasesDocument164 pagesPoli Digested CasesAthena SalasNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction CasesDocument19 pagesStatutory Construction CasesShiela BrownNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Provisions of TaxationDocument6 pagesConstitutional Provisions of TaxationSachieCasimiroNo ratings yet

- ABAKADA v. ERMITA | VAT Rate Increase UpheldDocument1 pageABAKADA v. ERMITA | VAT Rate Increase UpheldA M I R ANo ratings yet

- Tolentino Vs Secretary of FinanceDocument26 pagesTolentino Vs Secretary of FinanceMadelle Pineda100% (1)

- Lambert Vs FoxDocument1 pageLambert Vs FoxRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Baleros v. PeopleDocument4 pagesBaleros v. PeopleRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Parol - PNB Vs SeetoDocument3 pagesParol - PNB Vs SeetoRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Fort BonifacioDocument11 pagesFort BonifacioRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- ABAKADADocument65 pagesABAKADARavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Gonzales v. ViolaDocument2 pagesGonzales v. ViolaRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Phil HealthDocument10 pagesPhil HealthRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Intel TechDocument35 pagesIntel TechRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- PASNGADANDocument9 pagesPASNGADANRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Cir V Magsaysay LinesDocument5 pagesCir V Magsaysay LinesParis LisonNo ratings yet

- Contex V CirDocument7 pagesContex V CirParis LisonNo ratings yet

- CS GarmentsDocument18 pagesCS GarmentsRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- 5 - Paguia Vs Office of The PresidentDocument1 page5 - Paguia Vs Office of The PresidentRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- 49 - Poblete Vs CADocument2 pages49 - Poblete Vs CARavenFoxNo ratings yet

- 93 - OCA v. LiangcoDocument2 pages93 - OCA v. LiangcoRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Ulep Vs Legal ClinicDocument51 pagesUlep Vs Legal ClinicHowie MalikNo ratings yet

- Carandang vs Obmina - Atty suspension for failure to notify clientDocument2 pagesCarandang vs Obmina - Atty suspension for failure to notify clientRavenFox100% (1)

- 38 - Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company Vs ArguellesDocument2 pages38 - Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company Vs ArguellesRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Lee Vs TambagoDocument1 pageLee Vs TambagoRavenFox100% (1)

- 16 - Ciocon-Reer Vs LubaoDocument2 pages16 - Ciocon-Reer Vs LubaoRavenFox100% (1)

- IN THE MATTER OF THE INTESTATE ESTATE OF ANDRES G. DE JESUS AND BIBIANA ROXAS DE JESUS, SIMEON R. ROXAS & PEDRO ROXAS DE JESUS, Petitioners, vs. ANDRES R. DE JESUS, JRDocument5 pagesIN THE MATTER OF THE INTESTATE ESTATE OF ANDRES G. DE JESUS AND BIBIANA ROXAS DE JESUS, SIMEON R. ROXAS & PEDRO ROXAS DE JESUS, Petitioners, vs. ANDRES R. DE JESUS, JRPebs DrlieNo ratings yet

- 27 - Abella Vs CruzabraDocument2 pages27 - Abella Vs CruzabraRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Azuela vs. CADocument7 pagesAzuela vs. CAJoan ChristineNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Ignacio Conti Vs CADocument1 pageHeirs of Ignacio Conti Vs CARavenFox50% (2)

- 2 - Alvarado Vs GaviolaDocument8 pages2 - Alvarado Vs GaviolaRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Cordon CaseDocument22 pagesCordon CaseRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Court Case over Estate of Gliceria A. del RosarioDocument7 pagesCourt Case over Estate of Gliceria A. del RosariomepilaresNo ratings yet

- Vicente ChingDocument8 pagesVicente ChingRafael Derick Evangelista IIINo ratings yet

- Alawi v. Alauya A.M. SDC 97 2 P February 24 1997Document2 pagesAlawi v. Alauya A.M. SDC 97 2 P February 24 1997Kristell FerrerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2-Traditional Approach For Stock AnalysisDocument20 pagesChapter 2-Traditional Approach For Stock AnalysisPeterNo ratings yet

- Question Paper of MBA Second YearDocument5 pagesQuestion Paper of MBA Second YearKaran Veer SinghNo ratings yet

- Audit Mcom Part 2 Sem 3Document28 pagesAudit Mcom Part 2 Sem 3HimanshiShahNo ratings yet

- Republic v. MeralcoDocument2 pagesRepublic v. MeralcoJoyce Sumagang Reyes100% (1)

- Tasks IAS 38Document9 pagesTasks IAS 38Lolita IsakhanyanNo ratings yet

- Cost of Poor MaintenanceDocument11 pagesCost of Poor MaintenanceSaulo CabreraNo ratings yet

- ECON 301 CAT SolutionsDocument5 pagesECON 301 CAT SolutionsVictor Paul 'dekarNo ratings yet

- Module 8Document14 pagesModule 8ThuyDuongNo ratings yet

- Birla CableDocument4 pagesBirla Cablejanam shahNo ratings yet

- Acc 9 TestbankDocument143 pagesAcc 9 TestbankPaula de Torres100% (2)

- Congressman Bob Turner (NY-09) - Thursday 3-29 Home of Jennifer Saul RichDocument2 pagesCongressman Bob Turner (NY-09) - Thursday 3-29 Home of Jennifer Saul RichElizabeth BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Techno Tarp Polymers PVT LTDDocument63 pagesTechno Tarp Polymers PVT LTDMurtazaali BadriNo ratings yet

- SamHoustonState Fy 2020Document79 pagesSamHoustonState Fy 2020Matt BrownNo ratings yet

- Possible VAT Implications of Transfer PricingDocument12 pagesPossible VAT Implications of Transfer PricingPablo De La MotaNo ratings yet

- Informative Speech Outline LotteryDocument3 pagesInformative Speech Outline Lotteryapi-265257755No ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Property Plant and Equipment Depreciation and deDocument21 pagesChapter 13 Property Plant and Equipment Depreciation and deEarl Lalaine EscolNo ratings yet

- NCERT Class 11 Accountancy Book (Part II)Document124 pagesNCERT Class 11 Accountancy Book (Part II)Jidu M DivakaranNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs BOAC-Collector Vs LaraDocument6 pagesCIR Vs BOAC-Collector Vs LaraEmmanuel OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Classification of AccountsDocument6 pagesClassification of AccountsdddNo ratings yet

- CH 3 Multiple SolutionsDocument3 pagesCH 3 Multiple SolutionsSaleema KarimNo ratings yet

- Financial ManagementDocument238 pagesFinancial ManagementJherzy Henry Elijorde FloresNo ratings yet

- APGLI Scheme ExplainedDocument25 pagesAPGLI Scheme ExplainedLunjala TeluguNo ratings yet

- Ravi ResumeDocument3 pagesRavi ResumeKeerthanaNo ratings yet

- Customer Culture PDFDocument8 pagesCustomer Culture PDFRahilHakimNo ratings yet

- Jawaban AKM2Document10 pagesJawaban AKM2Jeaxell RieskyNo ratings yet

- Wal-Mart Stores' Discount OperationsDocument5 pagesWal-Mart Stores' Discount Operationsgaurav sahuNo ratings yet

- R12 ORACLE APPS module overviewDocument87 pagesR12 ORACLE APPS module overviewAllam ViswanadhNo ratings yet

- The Future of CruisingDocument7 pagesThe Future of CruisingAndreea DeeaNo ratings yet

- Good Notes For ReferenceDocument23 pagesGood Notes For ReferenceJoe EmmentalNo ratings yet

- LSCM Unit-IiDocument21 pagesLSCM Unit-IiGangadhara RaoNo ratings yet