Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Social Cognition and Peer Relations

Uploaded by

Eko Cahyono0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

56 views7 pagesss

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentss

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

56 views7 pagesSocial Cognition and Peer Relations

Uploaded by

Eko Cahyonoss

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

Social Cognition and Peer Relations

Insofar as children gradually acquire a theory of mind, it is reasonable to

ask about the implications of these conceptual changes for childrens wider social

behavior. Investigators who have examined this issue have focused on the

possibility that children with more advanced social cognition will perform better

on various measures of social interaction, particularly with peers.

This predicted link has emerged in several studies of

preschool children. Denham, McKinley, Couchoud, and Holt

(1990) examined the relationship between preschoolers

accuracy on an emotion-attribution task and their popularity

amongst peers. Children with a better understanding of the

causes of emotion were more popular with peers, even when the

effects of age and gender were controlled. In a study of hard-tomanage children, aged 3 and 4 years, Hughes, Dunn, and White

(1998) found that poor understanding of emotion was linked to

various interpersonal difficulties (e.g., antisocial behavior,

aggressiveness, restricted empathy, and limited prosocial

behavior), whereas Dunn and Cutting (1999) found that 4-yearolds with a good understanding of emotion cooperated and

communicated more effectively with a close friend during play.

Finally, in a longitudinal study of 4- and 5-year-olds, Edwards,

Manstead, and MacDonald (1984) found that accuracy in

identifying the expression of emotion was correlated with

popularity one or 2 years later, even when initial popularity was

taken into account.

A similar link between emotion understanding and peer

relationships has emerged among school-aged children. Dunn

and Herrera (1997) found that 6-year-olds ability to solve

interpersonal conflicts with their friends at school was predicted

by their emotion understanding at the age of 3 years. Cassidy,

Parke, Butkovsky, and Braungart (1992) reported a positive

relationship between childrens emotion understanding and their

popularity with peers during the 1st year of obligatory schooling.

Finally, in a study of 11- to 13-year-olds, Bosacki and Astington

(1999) found a positive relation between emotion understanding

and social skills as judged by teachers.

These various findings strongly suggest that the

understanding of mental states and notably the understanding of

emotion facilitates childrens interactions with peers both before

and during the school years. These are correlational findings, and

short of proving the link by means of an intervention study, we

cannot be certain of the exact causal relationship. Nevertheless,

the link between competence at the identification and analysis of

emotion and later peer relationships is encouraging.

On a more cautionary note, Cutting and Dunn (2002) found

that there are costs as well as benefits to superior social

cognition. Five-year-olds were assessed during their 1st year at

school for their sensitivity to teacher criticism. Childrens

understanding of false belief and mixed emotions measured 1

year earlier when they were in preschool proved to be a

good predictor of their sensitivity. More specifically, children who

showed a better understanding of thoughts and feelings in

preschool were likely to derogate their ability, when asked to

imagine receiving criticism from a teacher for a minor error. As

Cutting and Dunn (2002) point out, these findings raise important

questions about the longer-term impact of social cognitive skills.

On the positive side, they may indeed help children to navigate

the playground and peer relationships more effectively. At the

same time, they may render children more vulnerable to the

inevitable slings and arrows of social life, including interactions

with teachers.

Social Cognition and Trust

For the most part, investigators have neglected a domain

in which childrens social cognition is likely to have far-reaching

implications: their credulity with respect to other peoples claims.

Consider the dictum of the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher,

Thomas Reid (1764/1970): In a word, if credulity were the effect

of reasoning and experience, it must grow up and gather

strength, in the same proportion as reason and experience do.

But if it is a gift of nature, it will be the strongest in childhood,

and limited and restrained by experience; and the most

superficial view of human life shows, that the last is really the

case, and not the first (pp. 240241). Is there evidence that

children become less credulous with age? One of the central

findings in theory-of-mind research is that most normal children

beyond the age of 4 years realize that sincere claims and beliefs

may be false. It would be reasonable to expect that insight to

render children less credulous.

Indeed, recent findings confirm that preschoolers do

increasingly display selective trust and doubt in the claims made

by particular people (Clment, Koenig, & Harris, 2004; Harris &

Koenig, in press; Koenig, Clment, & Harris, 2004). When

preschoolers are presented with two informants, one of whom

makes various claims that the child knows to be true but the

other makes either false claims or confesses ignorance, they

subsequently trust the hitherto reliable informant but doubt the

hitherto unreliable informant. For example when shown an

unfamiliar object and offered different names for it by the two

informants, children trust the hitherto reliable informant.

Two developmental phases are apparent in childrens

selective trust (Koenig & Harris, 2005a). Three-yearolds trust a

hitherto reliable informant by seeking information from her

and endorsing her claims and doubt a self-confessedly

ignorant informant. They are less selective when invited to

choose between a reliable informant and an inaccurate

informant. Four-year-olds are selective in both cases: They trust a

reliable informant and they doubt not only an ignorant informant

but also an inaccurate informant. Arguably, 4-year-olds, attribute

inaccurate claims to an informants mistaken beliefs and adopt

an appropriately skeptical stance toward that persons later

assertions.

Beyond the particularities of the age change in trust and

doubt, these findings call attention to the way that children use

their emerging theory of mind to make trait attributions in the

cognitive sphere. After a brief exposure to a distinctive pattern of

reliability on the part of particular informants, preschoolers

anticipate that those informants will continue to differ in terms of

their future epistemic reliability. In some ways, there is nothing

remarkable about this result. Attachment theory has long

insisted, and provided evidence for, the claim that infants can

gather and retain information about a caregivers past emotional

availability and use that to forecast how he or she will respond in

the future. However, attachment theory has generally

emphasized the infants ability to anticipate a class of overt

behaviors on the part of a caregiver particularly, the

caregivers physical availability and emotional responsiveness.

The findings on selective epistemic trust suggest that

preschoolers are capable of a deeper type of attribution. They do

not base their trait attributions on particular regularities in the

overt behavior of their informants at the behavioral level,

mistaken claims have nothing in common with one another.

Rather, they base their predictions on regularities in the

psychological status and more specifically the epistemic

reliability, of their informants (Koenig & Harris, 2005b).

Further evidence that preschoolers are able to assess the

epistemic reliability of their informants and do not just focus on

behavioral regularities emerged in a study that examined the

scope of childrens attributions. As in prior experiments, 3- and 4year-olds were presented with two informants. One proved

reliable in that she named a set of familiar objects accurately;

the other informant, by contrast, proved unreliable in that she

admitting to not knowing the names of any of the objects.

Subsequently, children were shown various novel objects and

asked if they knew what they were for. Once they had

acknowledged not knowing, children were prompted to seek help

from either of the informants. In addition, each informant then

offered a different demonstration of what to do with the object.

Finally, children were asked to provide their own demonstration.

As in previous studies, children were selective: They tended to

ask for help from, and trust the help supplied by, the reliable as

opposed to the unreliable informant. Thus, after witnessing the

differential reliability of the informants in the verbal sphere,

children made a relatively global assessment of their epistemic

reliability. They displayed selective trust in the information that

the two informants provided in the nonverbal sphere of object

use (Koenig & Harris, 2005a).

Granted that children increasingly display selective trust

and doubt in particular informants how exactly is that selectivity

established? We may envisage two different mechanisms. In line

with the thrust of Reids dictum, children might start off by

trusting every informant on first encounter. To the extent that

informants continue to prove reliable (e.g., say nothing that

contradicts what the child knows already and respond

appropriately to questions) children would retain but not add

to their initial stock of trust in that informant. However,

whenever informants prove unreliable by acknowledging

ignorance in response to questions or by saying something the

child knows to be false children would accumulate doubt. On

this account, selectivity is brought about by growing doubt with

regard to unreliable informants rather than by any increment in

trust.

Consider, however, a reasonable alternative. Arguably,

children add to their stock of trust in an informant whenever he

or she makes a claim that the child knows to be correct. Thus,

children would be much more likely to believe the claims of

familiar as compared to unfamiliar informants. Familiar

informants unlike unfamiliar informants would generally

have ample opportunities to prove themselves trustworthy. On

this account, selectivity is brought about by cumulative trust in

reliable informants rather than by any increment in doubt.

The first model fits the intuition that a persons false

assertions are more distinctive and make a deeper impression

on us than their true assertions. For example, an evidently

false statement by a politician can dramatically undermine their

reputation for probity. The second model fits a different intuition,

namely that young children are especially likely to trust the

claims of familiar caregivers more than those of relative

strangers. Whichever model ultimately proves correct, it is clear

that the development of childrens epistemic trust is a tractable

but neglected domain of research in social cognition. To the

extent that theory-of-mind research has shown how young

children attribute mental states, the stage is set for

understanding how they make different attributions to different

individuals depending on their past history.

You might also like

- Pone 0172147Document12 pagesPone 0172147Eko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Acbt Penting Dentice Sputum ClearanceDocument42 pagesAcbt Penting Dentice Sputum ClearanceRahma HanifaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Acc Maju PDFDocument5 pagesJurnal Acc Maju PDFEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Istilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisDocument8 pagesIstilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Cooperation and Stress: Exploring The Differential Impact of Job Satisfaction, Communication and CultureDocument14 pagesCooperation and Stress: Exploring The Differential Impact of Job Satisfaction, Communication and CultureEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Pone 0149818Document11 pagesPone 0149818rachel0301No ratings yet

- Enforcing arbitration awards in IndonesiaDocument12 pagesEnforcing arbitration awards in IndonesiaEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Enforcing arbitration awards in IndonesiaDocument12 pagesEnforcing arbitration awards in IndonesiaEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Service Models Final February 2007Document39 pagesService Models Final February 2007Eko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Ros and PeDocument15 pagesRos and PeEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- L Arg PrevDocument6 pagesL Arg PrevEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Adma ArginineDocument5 pagesAdma ArginineEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Hypertension in Preeclampsia ADocument11 pagesPathophysiology of Hypertension in Preeclampsia AEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Regional Autonomy Policy's Impact on West Sumatra's Economic Growth Amid ASEAN IntegrationDocument9 pagesRegional Autonomy Policy's Impact on West Sumatra's Economic Growth Amid ASEAN IntegrationEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Istilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisDocument8 pagesIstilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Istilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisDocument8 pagesIstilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Supplementation During Pregnancy With L-Arginine and AnDocument10 pagesEffect of Supplementation During Pregnancy With L-Arginine and AnEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Hipoparatiroid - AntropometriDocument8 pagesJurnal Hipoparatiroid - AntropometriEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Istilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisDocument8 pagesIstilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Redesign PDFDocument18 pagesRedesign PDFEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Himne HimpaudiDocument1 pageHimne HimpaudiEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Measuring Nutritional Risk in HospitalsDocument8 pagesMeasuring Nutritional Risk in HospitalsEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Massive Hemoptysis: Resident Grand RoundsDocument7 pagesMassive Hemoptysis: Resident Grand RoundsEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Istilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisDocument8 pagesIstilah Pajak Indonesia-InggrisEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- 5C6DA578-C0B8-4292-A761-EA7CB5F0514EDocument9 pages5C6DA578-C0B8-4292-A761-EA7CB5F0514EEnab EnabaneNo ratings yet

- Rantaman Tanti NurhayaniDocument12 pagesRantaman Tanti NurhayaniEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Aromatase Inhibitors For Ovulation Induction and Ovarian StimulationDocument10 pagesAromatase Inhibitors For Ovulation Induction and Ovarian StimulationEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument12 pagesA Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Pone 0149818Document11 pagesPone 0149818rachel0301No ratings yet

- Adma ArginineDocument5 pagesAdma ArginineEko CahyonoNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- CANS-MH Manual PDFDocument35 pagesCANS-MH Manual PDFparaypanNo ratings yet

- CV Groh Website 080719Document11 pagesCV Groh Website 080719api-268780938No ratings yet

- Surviving Your Dissertation PDFDocument377 pagesSurviving Your Dissertation PDFlidieska67% (3)

- Encouraging ShopliftingDocument21 pagesEncouraging ShopliftingDadi Bangun WismantoroNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Corporate Social Respons PDFDocument18 pagesDeterminants of Corporate Social Respons PDFMahmoud YagoubiNo ratings yet

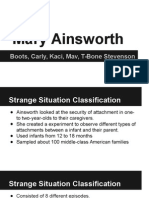

- Mary AinsworthDocument18 pagesMary Ainsworthapi-281084253No ratings yet

- Leaving Loneliness A Workbook - Building Relationships With Yourself and OthersDocument246 pagesLeaving Loneliness A Workbook - Building Relationships With Yourself and Othersteacher thaisNo ratings yet

- Lifter Et AlDocument21 pagesLifter Et AlLourdes DurandNo ratings yet

- Family Support in NICUDocument23 pagesFamily Support in NICUmotanul2No ratings yet

- Play TherapyDocument19 pagesPlay TherapyKing GilgameshNo ratings yet

- Life Story Therapy With Traumatized Children - A Model For PracticeDocument196 pagesLife Story Therapy With Traumatized Children - A Model For PracticeAlguém100% (1)

- Types and Distributions of Data Exam QsDocument2 pagesTypes and Distributions of Data Exam QsLouis PNo ratings yet

- Anne Carpentier - Stages of Child Development - From Conception Onward PDFDocument33 pagesAnne Carpentier - Stages of Child Development - From Conception Onward PDFGogutaNo ratings yet

- EFT Cheat Sheet-2Document1 pageEFT Cheat Sheet-2donnalinNo ratings yet

- Kopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Document8 pagesKopetski (1998) Parental Alienation Syndrome Part II. 27-MAR - COLAW - 61Shawn A. WygantNo ratings yet

- Topical Outline CompetentChildSpring2023Document4 pagesTopical Outline CompetentChildSpring2023AshpreetNo ratings yet

- Tugas EmilyDocument6 pagesTugas EmilyPitri YuliantiNo ratings yet

- Measuring Place Attachment: Developing Scales to Assess Symbolic and Functional DimensionsDocument8 pagesMeasuring Place Attachment: Developing Scales to Assess Symbolic and Functional DimensionsLathifahNo ratings yet

- Manual Autism AttachmentDocument26 pagesManual Autism AttachmentlolaaNo ratings yet

- The SociogramDocument8 pagesThe SociogramMa Nida BaldelobarNo ratings yet

- Children W/ OFW ParentsDocument22 pagesChildren W/ OFW Parentspinky giradoNo ratings yet

- Mudra2018 10.1016@j.jad.2018.07.024Document42 pagesMudra2018 10.1016@j.jad.2018.07.024Francisco Javier Salazar NúñezNo ratings yet

- Dissmissive AttachmentDocument19 pagesDissmissive AttachmentRobert WeathersNo ratings yet

- Influencer MarketingDocument11 pagesInfluencer MarketingHuong Giang VuNo ratings yet

- Core Concepts TheraplayDocument4 pagesCore Concepts TheraplayTrisha van Alen100% (1)

- Relationship Between Parenting Styles and Self Compassion in Young AdultsDocument11 pagesRelationship Between Parenting Styles and Self Compassion in Young AdultsShriya ShahNo ratings yet

- The Pathways To YouthDocument78 pagesThe Pathways To YouthjanachidambaramNo ratings yet

- (FONAGY) Mechanisms of Change in Mentalization Based TreatmentDocument20 pages(FONAGY) Mechanisms of Change in Mentalization Based TreatmentLuz Marina Franco YañezNo ratings yet

- Human Behaviour in EmergenciesDocument24 pagesHuman Behaviour in EmergenciesYanti YogyakartaNo ratings yet