Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Unpublished

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Unpublished

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

UNPUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 15-6003

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Petitioner - Appellee,

v.

PABLO RAMIREZ-ALANIZ,

Respondent - Appellant.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of North Carolina, at Raleigh.

W. Earl Britt, Senior

District Judge. (5:14-hc-02159-BR)

Argued:

December 9, 2015

Decided:

January 26, 2016

Before NIEMEYER, DUNCAN, and AGEE, Circuit Judges.

Affirmed by unpublished opinion.

Judge Niemeyer

opinion, in which Judge Duncan and Judge Agee joined.

wrote

the

ARGUED: Joseph Bart Gilbert, OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL PUBLIC

DEFENDER, Raleigh, North Carolina, for Appellant.

Robert J.

Dodson, OFFICE OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY, Raleigh, North

Carolina, for Appellee.

ON BRIEF: Thomas P. McNamara, Federal

Public Defender, OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER, Raleigh,

North Carolina, for Appellant. Thomas G. Walker, United States

Attorney, Jennifer P. May-Parker, Jennifer D. Dannels, Assistant

United States Attorneys, OFFICE OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY,

Raleigh, North Carolina, for Appellee.

Unpublished opinions are not binding precedent in this circuit.

NIEMEYER, Circuit Judge:

The

district

court

committed

Pablo

Ramirez-Alaniz,

Mexican national who had been charged with illegally reentering

the United States following deportation, to the custody and care

of the Attorney General pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 4246.

The court

found that Ramirez-Alaniz, who was being detained at the Federal

Medical Center in Butner, North Carolina (FMC Butner), for a

mental

health

evaluation

following

his

illegal

reentry,

was

suffering from a mental disease or defect as a result of which

his release [-- whether in the United States or Mexico --] would

create a substantial risk of bodily injury to another person or

serious damage to the property of another.

Ramirez-Alaniz now challenges this civil commitment order,

arguing that because he would be deported to Mexico if released,

the district courts finding of risk of danger to other persons

or

property

would

apply

to

persons

and

property

giving improper extraterritorial effect to 4246.

in

Mexico,

He notes

that the dangerousness prong [of 4246] applies [solely] to

effects within the United States, because the legislation fails

to

clearly

application.

indicate

that

Congress

intended

extraterritorial

(Emphasis added).

We conclude, however, that because the district court found

that Ramirez-Alanizs release would also pose a risk of danger

to persons or property in the United States, we need not reach

3

whether

4246

applies

extraterritorially.

Accordingly,

we

affirm, albeit on reasoning different from that given by the

district court.

I

In

Oregon

January

to

charges

apartment,

resisting

2011,

the

an

for

to

pleaded

discharging

firearm

Oregon

months imprisonment.

medication

Ramirez-Alaniz

relating

pointing

arrest,

after

at

state

another

court

guilty

firearm

in

in

his

individual,

and

sentenced

him

to

30

During his incarceration, he was given

mental

health

issues.

Thereafter,

he

was

deported to Mexico and prohibited from reentering the United

States.

About

two

weeks

later,

however,

on

December

6,

2012,

Ramirez-Alaniz was detained by border patrol agents in Arizona

and

charged

with

illegal

reentry

following

violation of 8 U.S.C. 1326(b)(2).

Alaniz

exhibited

inappropriate

poor

and

administration of medication.

staff

psychiatrist

adjustment,

noncompliance

sexually

with

the

As these conditions escalated, a

recommended

psychiatric hospital.

in

While detained, Ramirez-

institutional

behavior,

deportation,

his

transfer

to

an

inpatient

The district court in Arizona ordered

that Ramirez-Alaniz be evaluated for competency restoration and

treatment

under

18

U.S.C.

4241

and,

if

he

could

not

be

restored to competency, that Ramirez-Alaniz remain hospitalized

and undergo a dangerousness evaluation, pursuant to 18 U.S.C.

4246 and 4248.

Accordingly, Ramirez-Alaniz was transferred

to FMC Butner for evaluation and treatment.

A

panel

of

mental

health

evaluators

at

FMC

Butner

determined that Ramirez-Alaniz was incapable of proceeding with

the pending criminal case in the District of Arizona and that

his competency was unlikely to be restored in the foreseeable

future due to cognitive limitations.

In a subsequent forensic

evaluation completed in June 2014, the FMC Butner medical staff

concluded

that

Ramirez-Alaniz

was

suffering

from

mental

disease or defect as a result of which his release would create

a substantial risk of bodily injury to another person or serious

damage to the property of others.

On

receipt

initiated

Mental

the

of

4246(a),

this

present

Disease

District

of

or

North

and

forensic

proceeding

Defect

and

Carolina

on

the

commitment hearing.

evaluation,

by

filing

Dangerousness

July

district

court

22,

the

government

Certificate

in

2014,

the

see

thereafter

18

of

Eastern

U.S.C.

conducted

During the hearing, the court considered

forensic reports and testimony from Dr. Carlton Pyant, a staff

psychologist

at

FMC

Butner,

and

Dr.

Katayoun

Tabrizi,

psychiatrist appointed by the court, both of whom had evaluated

Ramirez-Alaniz.

5

Dr.

Pyant

diagnosed

Ramirez-Alaniz

as

suffering

from

schizophrenia, an unspecified neurodevelopmental disorder, and

an

alcohol

receiving

poor

use

disorder.

treatment

impulse

at

Dr.

FMC

control;

Pyant

Butner,

he

was

noted

that

prior

Ramirez-Alaniz

sexually

had

to

shown

provocative

and

dangerous; his speech was disorganized; his judgment [was]

poor;

he

substance

was

abuse;

himself.

been

hearing

and

voices;

he

was

he

engaged

essentially

in

significant

unable

to

control

Dr. Pyant reported, however, that Ramirez-Alaniz had

compliant

with

the

administration

of

medication

in

the

structured environment of FMC Butner and, with medication, had

demonstrated some insight into his behavior.

For example,

Ramirez-Alaniz told Dr. Pyant that the medication had helped to

stop the voices and prevent sexual thoughts.

Dr. Pyant also

noted that, with medication, Ramirez-Alaniz had been respectful

of

the

rights

cooperative

opinion

of

with

that

others,

staff.

had

positive

Nonetheless,

Ramirez-Alaniz

would

attitude,

Dr.

not

Pyant

was

continue

and

was

of

the

with

his

medications if released because he had made statements to that

effect and because he had minimal to no social support in the

United

States

to

ensure

medication

provide

necessary

compliance.

ongoing

Dr.

Pyant

supervision

also

noted

to

that

Ramirez-Alaniz was unable to provide a realistic plan to locate

appropriate

aftercare

resources.

6

Accordingly,

he

concluded

that Ramirez-Alaniz, if released, would pose a substantial risk

of

bodily

injury

to

other

persons

or

serious

damage

to

the

property of other persons.

Similarly,

schizophrenia,

disorder.

Dr.

an

She

Tabrizi

alcohol

also

diagnosed

use

made

intellectual disability.

Ramirez-Alaniz

disorder,

and

provisional

with

cocaine

diagnosis

use

of

an

She noted indicia of cognitive delays,

such as observations that Ramirez-Alaniz was unable to recall a

total of three words after the passing of five minutes, that he

could not state the current month, and that he could not perform

simple

arithmetic.

She

also

noted

several

factors

that

increased Ramirez-Alanizs risk for future violence, including a

psychotic

mental

health

illness;

history

of

firearm

possession, resisting arrest, drug use, and alcohol addiction;

and social obstacles, including unemployment and lack of social

support in the United States.

Ramirez-Alaniz

had

only

one

She emphasized, however, that

documented

episode

of

dangerous

behavior in the five years during which he lived in the United

States and that he had responded well to medication.

that,

with

medication,

Ramirez-Alaniz

was

She noted

respectful,

cooperative, and had a good sense of humor when she interviewed

him.

Ultimately, Dr. Tabrizi concluded that Ramirez-Alanizs

release

back

to

Arizona

for

deportation

would

not

create

substantial risk of bodily injury or damage to the property of

7

another in the United States, but this conclusion was based

primarily

on

her

assumption

that

Ramirez-Alaniz

would

be

deported to Mexico and, pending deportation, would remain in

custody.

try

to

While Dr. Tabrizi recognized that Ramirez-Alaniz might

reenter

discounted

this

the

United

States

risk

because

of

likelihood of his reentry.

Ramirez-Alaniz

were

to

be

after

the

deportation,

uncertainty

she

about

the

She recognized, however, that if

released

into

community

in

the

United States on his own, a problem would exist with his being

able to access mental health treatment and get his medications.

Accordingly,

Alaniz

would

she

agreed

meet

that

the

in

criteria

that

circumstance,

Ramirez-

for

civil

commitment

under

Ramirez-Alaniz

also

testified.

He

4246.

At

the

hearing,

expressed his willingness to receive medication to treat his

mental illness and stated, in view of his potential deportation,

that he wished to return to Mexico as soon as possible.

He

promised that, if deported, he would not return to the United

States without permission.

In argument to the district court, counsel for RamirezAlaniz stated his firm conviction that, if released, RamirezAlaniz would be deported to Mexico forthwith, noting that it

would be preposterous to assume that the government would not

deport him inasmuch as he is exactly the kind of person who

8

will

be

processed

for

deportation.

Consequently,

counsel

argued that Ramirez-Alaniz would not pose a risk to persons or

property in the United States.

that

immediate

deportation

The government argued, however,

was

not

sure

thing,

as

no

Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainer was then pending.

After receiving supplemental briefing on whether the reach of

4246 should be limited to persons and property in the United

States, the district court concluded that 4246 means that a

person should be civilly committed if he suffers from a mental

disease or defect as a result of which his release would create

a

substantial

regardless

of

risk

of

their

(Emphasis added).

bodily

injury

citizenship

or

to

another

geographic

person,

location.

The court then found, by clear and convincing

evidence, that [w]hether [Ramirez-Alaniz] is released in the

United States or his native Mexico, his release would pose a

high

risk

of

dangerousness

cognitive deficits.

given

his

(Emphasis added).

psychotic

disorder

and

Accordingly, the court

ordered that Ramirez-Alaniz be committed to the custody and care

of the Attorney General.

Following

district

court

the

in

district

Arizona

against

Ramirez-Alaniz.

order,

no

detainer,

courts

dismissed

Therefore,

criminal

commitment

the

criminal

following

proceeding,

the

or

order,

the

indictment

commitment

deportation

proceeding was -- nor currently is -- pending against RamirezAlaniz.

From the district courts civil commitment order, RamirezAlaniz

filed

this

appeal,

contending

that

4246

is

not

implicated by his circumstances because, if released, he would

be immediately deported to Mexico and 4246 applies only to

protect persons and property in the United States.

He argues

that the district court erred in construing 4246 to include

any risk to persons or property in Mexico.

II

Section 4246 of Title 18 provides that when the director of

a hospital facility certifies that a person in the custody of

the Bureau of Prisons or the Attorney General suffer[s] from a

mental disease or defect that would pose a substantial risk

of bodily injury to persons or serious damage to property, he

must, in the absence of suitable arrangements for state custody,

file the certificate in the district court where the person is

in custody, thus commencing a civil commitment proceeding.

U.S.C. 4246(a).

18

Upon notice to the person and the government,

the district court must then conduct a hearing to determine the

risk of the persons danger to other persons and property.

4246(a), (c).

Id.

If the court finds by clear and convincing

evidence that the person is presently suffering from a mental

10

disease or defect as a result of which his release would create

a substantial risk of bodily injury to another person or serious

damage to property of another, the court must commit the person

to the custody of the Attorney General.

In

this

case,

Ramirez-Alaniz

Id. 4246(d).

does

not

challenge

the

district courts finding that he would pose a substantial risk

of

bodily

injury

to

anothers property.

another

person

or

serious

damage

to

Rather, he argues that 4246 should not be

applied to commit him because he will be deported to Mexico and

the risk which the court found will be relevant only to persons

and property in Mexico, not to persons or property in the United

States.

Consequently,

finding

that

whether

he

is

he

reasons,

Ramirez-Alaniz

released

in

posed

the

the

a

district

risk

United

of

States

court,

in

dangerousness

or

his

native

Mexico, erred in construing 4246 to cover effects in Mexico.

(Emphasis added).

Stated otherwise, Ramirez-Alaniz argues that

the district court erred when it applied 4246 to persons and

property anywhere in the world, thus failing to recognize the

general presumption against the extraterritorial application of

statutes

absent

clear

congressional

expression

of

such

application.

The

promptly

government

deported,

argues

4246

that

even

provides

if

for

Ramirez-Alaniz

civil

is

commitment

regardless of the at-risk persons citizenship or geographical

11

location.

It also argues that Ramirez-Alanizs deportation is

not certain and that, if released, Ramirez-Alaniz would pose a

risk to persons and property in the United States.

Finally, the

government

were

argues

that

even

if

Ramirez-Alaniz

to

be

deported, his possible reentry would pose a substantial risk of

danger to persons or property in the United States given his

history of illegally reentering the country.

While Ramirez-Alaniz focuses his argument on the effect of

his conduct in Mexico, based on his assumption that if released,

he

would

be

deported

to

Mexico

immediately,

the

argument

overlooks the fact that if released, Ramirez-Alaniz would, based

on the record before us, be released into the United States.

There

is

no

proceeding

or

detainer

pending

against

Ramirez-

Alaniz that would preclude his presence in the United States

upon release.

And Ramirez-Alaniz has provided no factual basis

upon which to conclude that the district courts finding that

his release would pose a high risk of dangerousness [w]hether

he is released in the United States or his native Mexico was

clearly erroneous.

Alanizs

release

(Emphasis added).

would

pose

risk

Thus, because Ramirezof

danger

to

persons

or

property in the United States, we need not address his argument

that 4246 does not apply extraterritorially.

Ramirez-Alaniz also contends that even if his release would

pose some risk of danger to persons or property in the United

12

States, allowing a court in the United States to civilly commit

foreign nationals, such as him, who face possible deportation

would effectively commit such persons to serve de facto life

sentences at the expense of American taxpayers.

reading

absurd

4246

to

result

permit

and

these

would

life

raise

He argues that

sentences

serious

would

be

an

constitutional

questions.

We find this argument beset by speculation and hyperbole.

Section 4246 itself provides numerous avenues by which RamirezAlaniz

can

be

4246(d)(2),

released

(e),

(g).

after

commitment.

In

addition,

See

18

U.S.C.

Ramirez-Alaniz

has

challenged neither the governments statement at the commitment

hearing that it was exploring informal processes to move him to

Mexico

nor

the

governments

statement

in

its

brief

that

Immigration and Customs Enforcement still has the option to

initiate deportation proceedings against him even now that he

is civilly committed.

As to his concern regarding constitutional problems raised

by

the

district

courts

decision,

we

recognize

that

civil

commitment for any purpose constitutes a significant deprivation

of liberty that requires due process protection.

Texas, 441 U.S. 418, 425 (1979).

argue

that

hearing.

he

was

denied

due

Addington v.

But Ramirez-Alaniz does not

process

through

the

commitment

And whether due process would be denied with respect

13

to any future effort by him to obtain release can, at this time,

only be speculative.

At bottom, we affirm the civil commitment order based on

the

district

courts

finding

of

risk

of

harm

in

the

United

States, without determining whether 18 U.S.C. 4246 extends to

risks that Ramirez-Alanizs release might also pose outside the

United States.

AFFIRMED

14

You might also like

- Darrell Eugene Royal v. United States, 274 F.2d 846, 10th Cir. (1960)Document11 pagesDarrell Eugene Royal v. United States, 274 F.2d 846, 10th Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Dale Morehouse, 4th Cir. (2016)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Dale Morehouse, 4th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Frederick Springer, 4th Cir. (2013)Document26 pagesUnited States v. Frederick Springer, 4th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Wayne Franklin Schneider, 921 F.2d 272, 4th Cir. (1990)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Wayne Franklin Schneider, 921 F.2d 272, 4th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument5 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument17 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Johnny Williams, 4th Cir. (2014)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Johnny Williams, 4th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Sean Francis, 4th Cir. (2012)Document19 pagesUnited States v. Sean Francis, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Victoria Vamos, 797 F.2d 1146, 2d Cir. (1986)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Victoria Vamos, 797 F.2d 1146, 2d Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Reginald Jerome Love v. Aaron Johnson, Secretary of Correction Lacy Thornburg, Attorney General, 57 F.3d 1305, 4th Cir. (1995)Document17 pagesReginald Jerome Love v. Aaron Johnson, Secretary of Correction Lacy Thornburg, Attorney General, 57 F.3d 1305, 4th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. John Kanios, 4th Cir. (2015)Document5 pagesUnited States v. John Kanios, 4th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greenwood v. United States, 350 U.S. 366 (1956)Document8 pagesGreenwood v. United States, 350 U.S. 366 (1956)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Dennis Milton Wilson Riggleman, 411 F.2d 1190, 4th Cir. (1969)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Dennis Milton Wilson Riggleman, 411 F.2d 1190, 4th Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument5 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDocument22 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ronald L. Swain, 838 F.2d 468, 4th Cir. (1988)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Ronald L. Swain, 838 F.2d 468, 4th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument7 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Shinn VDocument3 pagesShinn Vapi-587137586No ratings yet

- United States v. Marvin J. Damon, 191 F.3d 561, 4th Cir. (1999)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Marvin J. Damon, 191 F.3d 561, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ernest J. Hendry v. United States, 418 F.2d 774, 2d Cir. (1969)Document13 pagesErnest J. Hendry v. United States, 418 F.2d 774, 2d Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. John W. Dzugas, 900 F.2d 256, 4th Cir. (1990)Document2 pagesUnited States v. John W. Dzugas, 900 F.2d 256, 4th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Alex Anderson, 104 F.3d 359, 4th Cir. (1996)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Alex Anderson, 104 F.3d 359, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Hill, 4th Cir. (2010)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Hill, 4th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Norman Blevins, 883 F.2d 70, 4th Cir. (1989)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Norman Blevins, 883 F.2d 70, 4th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Anderson, 4th Cir. (1996)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Anderson, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Darrel Fisher, 4th Cir. (2011)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Darrel Fisher, 4th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. White, 620 F.3d 401, 4th Cir. (2010)Document50 pagesUnited States v. White, 620 F.3d 401, 4th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed U.S. Court of Appeals Eleventh Circuit AUG 29, 2011 John Ley ClerkDocument63 pagesFiled U.S. Court of Appeals Eleventh Circuit AUG 29, 2011 John Ley Clerkarogers8239No ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitDocument63 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitLegal WriterNo ratings yet

- Lyskoski T. Washington v. Gershon Silber, Doctor, G. E. Deans, 993 F.2d 1541, 4th Cir. (1993)Document6 pagesLyskoski T. Washington v. Gershon Silber, Doctor, G. E. Deans, 993 F.2d 1541, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- FED COMPLAINT 2 8 18 FILED - AMENDED 5 8 2018 Bri Stephens PDFDocument63 pagesFED COMPLAINT 2 8 18 FILED - AMENDED 5 8 2018 Bri Stephens PDFPaul Charles D.No ratings yet

- United States v. Herriman, 10th Cir. (2014)Document28 pagesUnited States v. Herriman, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Monroe Cornish, 931 F.2d 887, 4th Cir. (1991)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Monroe Cornish, 931 F.2d 887, 4th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ruiz, 4th Cir. (2008)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Ruiz, 4th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Daniel J. Driscoll, 399 F.2d 135, 2d Cir. (1968)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Daniel J. Driscoll, 399 F.2d 135, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitDocument54 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitNocoJoeNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDocument30 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Terrence Smith, 4th Cir. (2013)Document19 pagesUnited States v. Terrence Smith, 4th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jo Ann Iverson, by Her Guardian Ad Litem, Carmel Iverson v. Arden Frandsen, 237 F.2d 898, 10th Cir. (1956)Document4 pagesJo Ann Iverson, by Her Guardian Ad Litem, Carmel Iverson v. Arden Frandsen, 237 F.2d 898, 10th Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Martinez-Hernandez, 4th Cir. (2010)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Martinez-Hernandez, 4th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Frye v. Lee, 4th Cir. (2000)Document18 pagesFrye v. Lee, 4th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. A.R., A Male Juvenile, A.R., 38 F.3d 699, 3rd Cir. (1994)Document11 pagesUnited States v. A.R., A Male Juvenile, A.R., 38 F.3d 699, 3rd Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument22 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument22 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Onrey Townes, 4th Cir. (2015)Document17 pagesUnited States v. Onrey Townes, 4th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Palacios, 677 F.3d 234, 4th Cir. (2012)Document24 pagesUnited States v. Palacios, 677 F.3d 234, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Zelaya, 4th Cir. (2009)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Zelaya, 4th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rob Corry Letter To John Walsh 1Document7 pagesRob Corry Letter To John Walsh 1NickNo ratings yet

- Court Remands Asylum Case Due to Insufficient Nexus EvidenceDocument13 pagesCourt Remands Asylum Case Due to Insufficient Nexus EvidenceReece CrothersNo ratings yet

- United States v. Corcino, 4th Cir. (2011)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Corcino, 4th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ronald Soobrian, 4th Cir. (2014)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Ronald Soobrian, 4th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Canaday Ruling On Jason Manuel ReevesDocument4 pagesCanaday Ruling On Jason Manuel ReevesmcooperkplcNo ratings yet

- United States v. Donald Kenneth Currens, 290 F.2d 751, 3rd Cir. (1961)Document35 pagesUnited States v. Donald Kenneth Currens, 290 F.2d 751, 3rd Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument14 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Knowlton V Richland County Et Al - Opinion and Order Re Summary JudgmentDocument30 pagesKnowlton V Richland County Et Al - Opinion and Order Re Summary JudgmentWKYC.comNo ratings yet

- United States v. McLamb, 4th Cir. (2009)Document4 pagesUnited States v. McLamb, 4th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Toby Garcia v. United States, 364 F.2d 306, 10th Cir. (1966)Document3 pagesToby Garcia v. United States, 364 F.2d 306, 10th Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

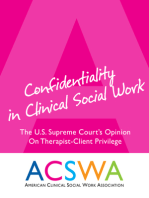

- Confidentiality In Clinical Social Work: An Opinion of the United States Supreme CourtFrom EverandConfidentiality In Clinical Social Work: An Opinion of the United States Supreme CourtNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Arnault vs. Nazareno, 87 Phils. 29Document2 pagesArnault vs. Nazareno, 87 Phils. 29Pauline DgmNo ratings yet

- Motion for Permanent DismissalDocument3 pagesMotion for Permanent DismissalAndro DayaoNo ratings yet

- CAse Digests - Legal EthicsDocument41 pagesCAse Digests - Legal EthicsRey Abz100% (1)

- Bus LawDocument64 pagesBus LawLawrence Bhobho67% (3)

- Dacanay Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesDacanay Vs PeopleKarina Katerin BertesNo ratings yet

- Queen Bench GuideDocument98 pagesQueen Bench GuidejamesborNo ratings yet

- Living Temple Workshop NotesDocument17 pagesLiving Temple Workshop NotesJ.p. Baron100% (1)

- Burgess v. Eforce Media, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 3Document3 pagesBurgess v. Eforce Media, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Hassan Awdi Story in Romania - Rodipet - Icsid World Bank - Story of An Investor enDocument16 pagesHassan Awdi Story in Romania - Rodipet - Icsid World Bank - Story of An Investor enHassan Awdi100% (1)

- Frauds in InsuranceDocument47 pagesFrauds in InsuranceVarsha Singh25% (4)

- White Collar Criminal Law Expla - Randall D EllasonDocument248 pagesWhite Collar Criminal Law Expla - Randall D EllasonSyed Amir IqbalNo ratings yet

- People v. DillardDocument1 pagePeople v. DillardcrlstinaaaNo ratings yet

- Deputy Secretary of State Staiert IEC Audit RequestDocument6 pagesDeputy Secretary of State Staiert IEC Audit RequestColorado Ethics Watch100% (1)

- Ateneo de Manila University Philippine StudiesDocument28 pagesAteneo de Manila University Philippine StudiesPAULINE ALAIZA MERCADONo ratings yet

- Filinvest Credit Corp vs IAC - Moral Damages Reduced Due to Short Seizure PeriodDocument101 pagesFilinvest Credit Corp vs IAC - Moral Damages Reduced Due to Short Seizure PeriodJenifer PaglinawanNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines vs. Sandiganbayan, Major General Josephus Q. Ramas and Elizabeth DimaanoDocument15 pagesRepublic of The Philippines vs. Sandiganbayan, Major General Josephus Q. Ramas and Elizabeth DimaanoAubrey AquinoNo ratings yet

- Grave Threat CasesDocument52 pagesGrave Threat Casesdaniel besina jr100% (2)

- Abdullahi v. Pfizer PDFDocument41 pagesAbdullahi v. Pfizer PDFAnonymous gOPgcJDNo ratings yet

- World Wide Web V PeopleDocument3 pagesWorld Wide Web V PeopleASGarcia24No ratings yet

- 172 Paredes Vs ManaloDocument2 pages172 Paredes Vs ManaloRae Angela GarciaNo ratings yet

- Defenses - LibelDocument7 pagesDefenses - LibelBey VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Scott Pasch Civic Development Group COPS Lawsuit From 2009Document29 pagesScott Pasch Civic Development Group COPS Lawsuit From 2009BadgeFraudNo ratings yet

- People v. BorinagaDocument1 pagePeople v. BorinagaRiann BilbaoNo ratings yet

- GSK V Malik PDFDocument1 pageGSK V Malik PDFImma Coney OlayanNo ratings yet

- Legal Opinion on Bigamy CaseDocument6 pagesLegal Opinion on Bigamy CaseGeorge Panda100% (1)

- Principles of Corporate PersonalityDocument27 pagesPrinciples of Corporate PersonalityLusajo Mwakibinga100% (1)

- SUN INSURANCE OFFICE v. MAXIMIANO C. ASUNCIONDocument11 pagesSUN INSURANCE OFFICE v. MAXIMIANO C. ASUNCIONAkiNo ratings yet

- Timothy Scott Sherman v. William L. Smith, Warden, Maryland House of Correction Annex John Joseph Curran, Attorney General For The State of Maryland, 70 F.3d 1263, 4th Cir. (1995)Document6 pagesTimothy Scott Sherman v. William L. Smith, Warden, Maryland House of Correction Annex John Joseph Curran, Attorney General For The State of Maryland, 70 F.3d 1263, 4th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- G0913291Document213 pagesG0913291edo-peiraias.blogspot.com100% (1)

- Gabrito vs. Court of Appeals 167 SCRA 771, November 24, 1988Document12 pagesGabrito vs. Court of Appeals 167 SCRA 771, November 24, 1988mary elenor adagioNo ratings yet