Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sayyid On Rituals Ideals and Reading The Quran

Uploaded by

mehmetmsahinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sayyid On Rituals Ideals and Reading The Quran

Uploaded by

mehmetmsahinCopyright:

Available Formats

Rituals, Ideals, and Reading the Quran

S. Sayyid

As Muslims, we revere the Quran as an object, allotting it pride of place in our homes, treating it

with care, keeping it bound nicely (if not ornamentally), and using it as a trump card to win

arguments with our Muslim friends. We seem, however, less able or willing to accord it the

respect it deserves as a text. To suggest that most Muslims do not treat the text with respect

seems to fly in the face of many believers experience, for do we not take its verses and make

amulets out of them, place them around our homes and other buildings, and incorporate them in

our prayers? Surely, this suggests that Muslims do respect the Quranic text. By respecting the

text, I mean undertaking a reading critically shaped by our awareness of God as All-Powerful

and All-Knowing, whose effects can be gleaned in the Quranic language like footprints in the

snow, but whose infinite majesty invariably escapes our limited comprehension. In other words,

respecting the Quran means recognizing the nature of its textuality, recognizing the way it is

written.

Muslims Believe that the Quran is the Record of What God Said to the Prophet (pbuh)

For Muslims, reading the Quran has a unique significance that it cannot have for non-Muslims,

be they politicians, columnists, polemicists doubling as scholars, or even serious scholars. I

would argue that for non-Muslims, the Qurans significance is secondary, in that its importance

is derived from the value that Muslims place on it. While anyone can have an opinion about the

Quran, it is the Muslims opinion that is of primary importance, for, as a collective body,

Muslims comprise its main stakeholders.

Others may hold opinions that could influence Muslim opinion, but they have no direct access to

the Qurans significance. This has to be stated forcefully, since there is a tendency among

western Orientalists and polemicists to claim some sort of expertise in the field of Quranic

studies, which is viewed as superseding the understanding of inexpert or untutored Muslims.

This claim of expertise, which is reinforced by the Wests supremacist discourse, has to be

rejected, for what matters is how Muslims read the Quran, for only Muslims believe that the

Quran truly matters.1 In what follows, I confine my remarks to the relationship between Muslims

and the Quran.

At the heart of the Quran-ummah nexus is a fundamental tension arising from the attempts of

historically located finite beings to comprehend the transcendental Infinite. The major challenge

in any reading of the Quran goes beyond such linguistic difficulties as the divergence between

the Arabic of the prophetic era and of the contemporary era or the challenge of translating

1/4

Rituals, Ideals, and Reading the Quran

Arabic into other contemporary languages. The major challenge is philosophical and has to do

with how we read the Quran with respect to the power of its revelation. In other words, what

kind of text is the Quran?

Different texts imply different types of reading strategies. We do not read a shopping list the

same way we read a poem, or the manual that tells us how to program our cars navigation

system the same way we read a novel. The Quran is not like the New Testament, the first four

books of which can be described without too much difficulty as a biography of Jesus as told by

four different writers. It is true that the Quran has elements of various prophets biographies

(e.g., Moses and Joseph), but providing such information is not its main function. Nor is the

Quran simply a set of instructions, although it contains such elements.2 The Quran is not

organized in a narrative or a chronological form, for its verses are not patterned in terms of

length, while the surahs eschew a straightforward linearity.

Reading the Quran means reading a non-linear text, for unlike most texts, it is not structured in

linear sequences. We cannot use all of a languages words at once, for their sequencing

structures our meaning. Given that sentences are organized linearly, reading a non-linear text is

not an easy task. Of course, Muslims are helped in this endeavor by the way the Quran asserts

its role as a guide accessible to all those who wish to be guided. Thus, there is a suggestion

that those who seek guidance from the Quran will find it, despite the complexities of its

textuality, and will succeed in unveiling its verses meaning. I will return to this point a little later.

Now, I turn to the way Muslims want to use the Quran as the foundation for a political order, an

amalgam of ideas that has found popular expression in the slogan the Quran is our

constitution. How can the Quran be read as the source of a constitutional order?

It is estimated that out of the Qurans 6,238 verses, at least 228 of them refer to public affairs

and the regulation of socioeconomic, and legal relations. 3 This suggests that the Quran clearly

presents itself as a text that cannot be contained within the confines of the post-Enlightenment

(western) Christian definition of a distinct religious sphere.4 This seems to allow Muslims to use

the Quran to found a constitution and, of course, this is what many Muslims attempt to do. For

example, recently a group of Muslims in the United States (viz., the Progressive Muslim Union)

drafted an ideal Islamic constitution.5 Its various clauses are introduced with a citation from the

Quran, which is supposed to justify the documents relevant clause. Thus, Quranic citations

serve as prefixes to the clauses of a document that bears a strong (structural) resemblance to

the American constitution (e.g., similar vocabulary and similar notions of division of powers).

More literal-minded Muslims may exclaim that this is only to be expected from a group calling

itself Progressive Muslims; however, precisely the same strategy is followed by Hizb ut-Tahrir.6

Even those Muslims who have less overtly political concerns use this strategy of citation to

buttress their viewpoints.

2/4

Rituals, Ideals, and Reading the Quran

There are two difficulties with following this strategy that I would like to consider. First, there is

the common problem of selecting the various citations. Second, there is the problem of

interpretation. To be fair, astute readers of the Quran are aware of these problems. Their

solution to these problems is to make an important distinction between the Quran as divine and

immutable, and its reading as historically conditioned and mundane (e.g., Asma Barlas and

Tariq Ramadan).7 This is a fairly standard way of proceeding, and there is nothing wrong with it.

However, a third and less obvious difficulty is of more critical importance and has to do with the

differences between the Quran and legal or constitutional texts.

Legal codes have to be structured in particular ways and constructed in a linear fashion. One of

the most common reading strategies is to discover the authors intention, for legal disputes often

entail deciphering thelegislators intention in promulgating a particular law. As Farid Esack

points out, this is very difficult to do when the author is Divine, All-Knowing, and All-Mighty.8 We

cannot access the mind of God, and attempts to transcend our fundamental limitations lead to

what might be best described as spiritual positivism,9 namely, the attempt to use scientific

discourse to compensate for our limited ability to understand the mind of the Divine; thus, for

example, concluding that pork and alcohol are forbidden to Muslims for health reasons. In other

words, lacking access to Gods mind causes us to resort to using a human tool (science) to

reveal the divine will.

Superficially, this seems like an attempt to make science serve God. However, in reality it

entails privileging the scientific discourse over Revelation, thus leading to the divinization of

science. Since it makes the logic of God equivalent to the findings of science itself, God

becomes the object of scientific laws uncovered by human minds. Such an approach confuses

scientific descriptions of the universe with the reality of the universe itself. This leads to an

epistemological fallacy in which scientific descriptions of creation are taken as creation itself or,

otherwise stated, scientific descriptions of reality are considered to be reality itself. (For

example, some commentators see the one electron of the hydrogen atom as a confirmation of

tawhid [unity]. Of course, this example made more sense when science did not consider that

there was anything smaller. Clearly, in a world of quarks and strange attractors, it becomes

more difficult to sustain the one electron one God view.)

The positivist strategy toward knowing God is deeply flawed, both in epistemological terms

(there is no reason to assume that scientific descriptions are more accurate in themselves than

other kinds of descriptions [e.g., a flower described by a biologist is not more of a flower than

one described by a poet, given that the descriptions serve different purposes]) and in Muslim

theological terms (by making the Divine secondary to science, which is a human endeavor, one

closes the gap between the human and the Divine, which leads to diminishing the Divine to the

level of the human). Positivist readings of the Quran cannot help us know the mind of God or

assist in any attempt to construct a legal framework from the Quran.

3/4

Rituals, Ideals, and Reading the Quran

click for a full paper in pdf

4/4

You might also like

- Kantianism - Britannica Online EncyclopediaDocument12 pagesKantianism - Britannica Online EncyclopediamehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Selected Topics in Economy and Society in Turkey 1968 in Comparative PerspectiveDocument4 pagesSelected Topics in Economy and Society in Turkey 1968 in Comparative PerspectivemehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Nietzsche's Critique of Positivism - Existence and The OneDocument16 pagesNietzsche's Critique of Positivism - Existence and The OnemehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Bulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsDocument11 pagesBulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Mind Volume 21 Issue 81 1912 (Doi 10.2307/2248912) Review by - F. C. S. Schiller - Die Philosophie Des Als Ob. System Der Theoretischen, Praktischen Und Religiosen Fiktionen Der Menschheit Auf GrundDocument13 pagesMind Volume 21 Issue 81 1912 (Doi 10.2307/2248912) Review by - F. C. S. Schiller - Die Philosophie Des Als Ob. System Der Theoretischen, Praktischen Und Religiosen Fiktionen Der Menschheit Auf GrundmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Liberal Arts Speech8Document16 pagesLiberal Arts Speech8mehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Newspaper TemplateDocument6 pagesNewspaper TemplatemehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Social OntologyDocument771 pagesSocial OntologyJoey Carter100% (1)

- July 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishDocument24 pagesJuly 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Zuckert, Nature, History, and The Self - Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations - History - Historicism PDFDocument16 pagesZuckert, Nature, History, and The Self - Nietzsche's Untimely Considerations - History - Historicism PDFmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Bulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsDocument11 pagesBulliet Pages From A Memoir Methodists and MuslimsmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- July 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishDocument24 pagesJuly 15 Coup Attempt-15temmuz-EnglishmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- İlhan Uzgel, "Between Praetorianism and Democracy The Role of The Military in Turkish Foreign Policy", The Turkish YearbookDocument35 pagesİlhan Uzgel, "Between Praetorianism and Democracy The Role of The Military in Turkish Foreign Policy", The Turkish YearbookmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Newspaper TemplateDocument6 pagesNewspaper TemplatemehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Ash - The Emergence of Gestalt Theory - Experimental Psychology in Germany, 1890-1920 - PHD ThesisDocument661 pagesAsh - The Emergence of Gestalt Theory - Experimental Psychology in Germany, 1890-1920 - PHD Thesismehmetmsahin100% (1)

- Schutz - Concept and Theory Formation in The Social SciencesDocument17 pagesSchutz - Concept and Theory Formation in The Social SciencesmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Critique of DuerrDocument6 pagesCritique of DuerrmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- The Heythrop Journal Volume 48 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1111/j.1468-2265.2007.00315.x) Benjamin D. Crowe - Nietzsche, The Cross, and The Nature of GodDocument17 pagesThe Heythrop Journal Volume 48 Issue 2 2007 (Doi 10.1111/j.1468-2265.2007.00315.x) Benjamin D. Crowe - Nietzsche, The Cross, and The Nature of GodmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Discover the Ancient Logic of Topics in Toulmin's Modern Theory of Inference WarrantsDocument7 pagesDiscover the Ancient Logic of Topics in Toulmin's Modern Theory of Inference WarrantsmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Syrians in Turkey The Economics of IntegrationDocument10 pagesSyrians in Turkey The Economics of IntegrationmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Ernst Kantorowicz Humanities and HistoryDocument3 pagesErnst Kantorowicz Humanities and HistorymehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Ps 589 - State Formation and Political Regimes - Syllabus - Fall 2014Document20 pagesPs 589 - State Formation and Political Regimes - Syllabus - Fall 2014mehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Walton - Beyond Convivencia and Conflict - Reflections On The History and Memory of Andalusian and Ottoman Religious BelongingDocument7 pagesWalton - Beyond Convivencia and Conflict - Reflections On The History and Memory of Andalusian and Ottoman Religious BelongingmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Otto Bird - The Tradition of The Logical Topics - Aristotle To OckhamDocument18 pagesOtto Bird - The Tradition of The Logical Topics - Aristotle To OckhammehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Strauss ModernitysThreeWavesDocument9 pagesStrauss ModernitysThreeWavesV_ctor_Manuel__7561No ratings yet

- Stack - Value and FactsDocument12 pagesStack - Value and FactsmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Dhaouadi - Interview With Smelser - Social Sciences in CrisisDocument8 pagesDhaouadi - Interview With Smelser - Social Sciences in CrisismehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Baber Johansen - Islamic Modernism (1) HDS2014FallIslModernisCorrFinVersSept15Document4 pagesBaber Johansen - Islamic Modernism (1) HDS2014FallIslModernisCorrFinVersSept15mehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- Tastan - Gezi Park Protests in Turkey: A Qualitative Field ResearchDocument12 pagesTastan - Gezi Park Protests in Turkey: A Qualitative Field ResearchmehmetmsahinNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Class VII 2019 2020 SyllabusDocument15 pagesClass VII 2019 2020 SyllabusShweta JainNo ratings yet

- Podcast Script - Grade 12 Ma. April L. Gueta Creative Nonfiction Quarter 2-Module 1 Second Quarter, SY 2021-2022Document2 pagesPodcast Script - Grade 12 Ma. April L. Gueta Creative Nonfiction Quarter 2-Module 1 Second Quarter, SY 2021-2022LillienneNo ratings yet

- 8001 w13 Ms 11Document6 pages8001 w13 Ms 11mrustudy12345678No ratings yet

- Shopping For Clothes - Exercises 4 PDFDocument2 pagesShopping For Clothes - Exercises 4 PDFelif nutNo ratings yet

- Blueprint For Ell Success 2Document5 pagesBlueprint For Ell Success 2lychiemarliaNo ratings yet

- Fbe - EcuadorDocument7 pagesFbe - EcuadorJoselyn VelasquezNo ratings yet

- 4 WAYS TO KNOW YOUR PITCH PATTERNSDocument1 page4 WAYS TO KNOW YOUR PITCH PATTERNSPablo Terraza CendoyaNo ratings yet

- MANTHRASDocument62 pagesMANTHRASVaithy Nathan100% (1)

- WEEK 5: WHAT DAY IS IT TODAY? LESSON ONEDocument2 pagesWEEK 5: WHAT DAY IS IT TODAY? LESSON ONEhuyen nguyenNo ratings yet

- All Long Vowels Please Stand Up!: Learning ObjectivesDocument8 pagesAll Long Vowels Please Stand Up!: Learning ObjectivesRonnaliza CorpinNo ratings yet

- Rubyscript2Exe - A Ruby CompilerDocument19 pagesRubyscript2Exe - A Ruby Compilera4agarwalNo ratings yet

- Syntactic Stylistic DevicesDocument9 pagesSyntactic Stylistic DevicesAlexandra100% (6)

- Test Unit 1 Level 2 1BACDocument3 pagesTest Unit 1 Level 2 1BACRaquel Villalain Sotil100% (1)

- Moy Ya Lim Yao V Comm of ImmigrationDocument2 pagesMoy Ya Lim Yao V Comm of ImmigrationPam Ramos100% (3)

- Spanish 3 A Curriculum MapDocument9 pagesSpanish 3 A Curriculum MapChristelle Liviero AracenaNo ratings yet

- English: First Quarter - Module 4Document8 pagesEnglish: First Quarter - Module 4Angelica AcordaNo ratings yet

- Integrated Language Environment: AS/400 E-Series I-SeriesDocument15 pagesIntegrated Language Environment: AS/400 E-Series I-SeriesrajuNo ratings yet

- Class 12 TopicsDocument43 pagesClass 12 Topicsgideontargrave7No ratings yet

- WritingDocument91 pagesWritingSai RemaNo ratings yet

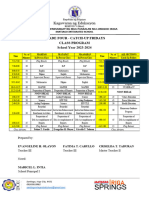

- Class Program G4 Catch UpDocument1 pageClass Program G4 Catch UpEvangeline D. HertezNo ratings yet

- Patient Communication PDFDocument16 pagesPatient Communication PDFraynanthaNo ratings yet

- Cognitive StylisticsDocument4 pagesCognitive StylisticsTamoor AliNo ratings yet

- Pragmatics of Speech Actions Hops 2: Unauthenticated Download Date - 6/3/16 11:21 AmDocument744 pagesPragmatics of Speech Actions Hops 2: Unauthenticated Download Date - 6/3/16 11:21 AmVictor Almeida100% (1)

- Alleyns 11 English Sample Paper 1Document14 pagesAlleyns 11 English Sample Paper 1VivianNo ratings yet

- Absolute Beginner S1 #1 Learning To Say Hello in Swahili: Lesson NotesDocument6 pagesAbsolute Beginner S1 #1 Learning To Say Hello in Swahili: Lesson NotesDaniel tesfayNo ratings yet

- Introduction To JurisprudenceDocument7 pagesIntroduction To JurisprudenceDheeraj AseriNo ratings yet

- Oops Notes (C++) By:yatendra KashyapDocument39 pagesOops Notes (C++) By:yatendra Kashyapyatendra kashyap86% (7)

- English Grammar CohesionDocument1 pageEnglish Grammar Cohesionbutterball100% (1)

- Dawood Public School Course Outline 2018-19 Art & Craft Grade IIDocument5 pagesDawood Public School Course Outline 2018-19 Art & Craft Grade IISyed Mujahid AliNo ratings yet

- Humanities German PaperDocument93 pagesHumanities German PaperTanya KothariNo ratings yet