Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2012 Ludwig's Angina - An Emergency

Uploaded by

Miguel Angel Carrasco MedinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2012 Ludwig's Angina - An Emergency

Uploaded by

Miguel Angel Carrasco MedinaCopyright:

Available Formats

[Downloaded free from http://www.jnsbm.org on Sunday, September 18, 2016, IP: 181.64.152.

168]

Case R e po r t

Ludwigs Angina An emergency: A case report

with literature review

Ramesh Candamourty,

Suresh Venkatachalam,

M. R. Ramesh Babu1,

G. Suresh Kumar

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Indira Gandhi Institute of Dental Sciences, Mahatma

Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute Campus, Pillaiyarkuppam, Pondicherry, 1Department

of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Mahatma Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Dental Sciences,

Pondicherry, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Ramesh Candamourty, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Indira Gandhi Institute of

Dental Sciences, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute Campus, Pillaiyarkuppam,

Pondicherry 607 402, India. E-mail: ramesh_candy@rediffmail.com

Abstract

Ludwigs angina is a form of severe diffuse cellulitis that presents an acute onset and spreads rapidly, bilaterally affecting the

submandibular, sublingual and submental spaces resulting in a state of emergency. Early diagnosis and immediate treatment

planning could be a life-saving procedure. Here we report a case of wide spread odontogenic infection extending to the neck with

elevation of the floor of the mouth obstructing the airway which resulted in breathlessness and stridor for which the patient was

directed to maintain his airway by elective tracheostomy and subsequent drainage of the potentially involved spaces. Late stages

of the disease should be addressed immediately and given special importance towards the maintenance of airway followed by

surgical decompression under antibiotic coverage. The appropriate use of parenteral antibiotics, airway protection techniques,

and formal surgical drainage of the infection remains the standard protocol of treatment in advanced cases of Ludwigs angina.

Key words: Ludwigs angina, odontogenic infection, surgical decompression, tracheostomy

INTRODUCTION

mortality currently averages approximately 8%.[2,3]

Ludwigs angina was coined after the German physician,

Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig who first described this

condition in 1836 as a rapidly and frequently fatal progressive

gangrenous cellulitis and edema of the soft tissues of the

neck and floor of the mouth.[1] With progressive swelling

of the soft tissues and elevation and posterior displacement

of the tongue, the most life-threatening complication

of Ludwigs angina is airway obstruction. Prior to the

development of antibiotics, mortality for Ludwigs angina

exceeded 50%.[2] As a result of antibiotic therapy, along

with improved imaging modalities and surgical techniques,

In Ludwigs angina, the submandibular space is the

primary site of infection.[4] This space is subdivided by the

mylohyoid muscle into the sublingual space superiorly and

the submaxillary space inferiorly. The majority of cases

of Ludwigs angina are odontogenic in etiology, primarily

resulting from infections of the second and third molars.

The roots of these teeth penetrate the mylohyoid ridge

such that any abscess, or dental infection, has direct access

to the submaxillary space. Once infection develops, it

spreads contiguously to the sublingual space. Infection can

also spread contiguously to involve the pharyngomaxillary

and retropharyngeal spaces, thereby encircling the airway.

Access this article online

Other causes include peritonsillar or parapharangeal

abscesses, mandibular fractures, oral lacerations/piercing

or submandibular sialadenitis, and oral malignancy.[5]

Predisposing factors include dental caries, recent dental

treatment, systemic illness such as diabetes mellitus,

malnutrition, alcoholism, compromised immune system

such as AIDS and organ transplantation.[6-9] Without

Quick Response Code:

Website:

www.jnsbm.org

DOI:

10.4103/0976-9668.101932

Journal of Natural Science, Biology and Medicine | July 2012 | Vol 3 | Issue 2

206

[Downloaded free from http://www.jnsbm.org on Sunday, September 18, 2016, IP: 181.64.152.168]

Candamourty, et al.: Emergency management of Ludwigs angina

a treatment, it is frequently fatal from the risk of

asphyxia with a mortality rate of 50%. The aggressive

surgical intervention, the antibiotic introduction, and the

improvement of dental care have determined a significant

reduction of the mortality rate to less than 10%.[10]

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old gentleman reported to the Department of

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery with a chief complaint of

inability to open the mouth, pain, and swelling in relation to

the lower jaw and neck since a day. On physical examination,

he had respiratory distress and was toxic in appearance and

his vital signs were monitored immediately. His temperature

was 101.8F with a pulse rate of 106 beats per minute,

blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg, and a respiratory rate

of 25 breaths per minute. Mouth opening was limited to

1.5 cm (interincisal distance) and revealed grossly decayed

lower right second molar tooth with drainage of pus. Extraoral swelling was indurated, nonfluctuant with bilateral

involvement of the submandibular and sublingual glands

[Figure 1]. An immediate diagnosis of Ludwigs angina was

made, and the patient was posted for surgical decompression

under general anesthesia. However, elective tracheostomy

was planned for airway maintenance with the help of an

otolaryngologist. The blood report was normal except

for raise in ESR, eosinophilia. Elective tracheostomy was

done under local anesthesia, airway secured and general

anesthesia was provided. Separate stab incisions was made

in relation to the submandibular space bilaterally and

submental space. A sinus forceps was introduced to open

up the tissue spaces and pus was drained. The wound

was irrigated with normal saline, and a separate tube

drain was placed and secured to the skin with silk sutures

[Figure 2]. Intravenous administration of cefotaxime 1 g Bd,

gentamycin 80 mg Bd, metrogyl 500 mg, Tid were given for

5 days with a tapering dose of decadran 84 mg Bd for first

two postoperative days. Postoperative irrigation was done

through the drain which was removed after 36 h along with

the infected tooth. Tracheostomy tube care was taken in the

postoperative period, and the skin was strapped on the fifth

postoperative day after the removal of the tracheostomy

tube. Patient recovery was satisfactory.

DISCUSSION

Ludwigs angina and deep neck infections are dangerous

because of their normal tendency to cause edema,

distortion, and obstruction of airway and may arise as

a consequence of airway management mishaps. In the

early stages of the disease, patients may be managed

with observation and intravenous antibiotics. Advanced

infections require the airway to be secured with surgical

207

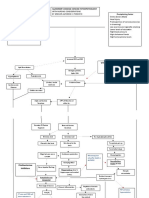

Figure 1: Preoperative appearance with bilateral involvement of the

submandibular, sublingual, and the submental spaces showing brawny

induration of the swelling

Figure 2: Postoperative view showing the tube drains and tracheostomy

tube in place

drainage. This is complicated by pain, trismus, airway

edema, and tongue displacement creating a compromised

airway.

-hemolytic streptococcus associated with anaerobic germs

such as peptostreptococcus and pigmented bacteroides

have been described as causative agents. Streptococcus viridans

(40.9%), Staphylococcus aureus (27.3%), and Staphylococcus

epidermis (22.7%) were isolated from deep neck infections.

Intravenous penicillin G, clindamycin or metronidazole

are the antibiotics recommended for use prior to obtaining

culture and antibiogram results. Some authors also

recommend the association of gentamycin.[11,12] Recent case

reports advocated the use of intravenous steroids which

potentially avoided the need for airway management.[1,4]

If patients present with swelling, pain, elevation of the

tongue, malaise, fever, neck swelling, and dysphagia, the

Journal of Natural Science, Biology and Medicine | July 2012 | Vol 3 | Issue 2

[Downloaded free from http://www.jnsbm.org on Sunday, September 18, 2016, IP: 181.64.152.168]

Candamourty, et al.: Emergency management of Ludwigs angina

submandibular area can be indurated, sometimes with

palpable crepitus. Inability to swallow saliva and stridor

raise concern because of imminent airway compromise.

The most feared complication is airway obstruction

due to elevation and posterior displacement of the

tongue.[3] To reduce the risk of spread of infection, needle

drainage can be performed.[13]

Airway compromise is always synonymous with the

term Ludwigs angina, and it is the leading cause of

death. Therefore, airway management is the primary

therapeutic concern. [3] The stage of the disease and

comorbid conditions at the time of presentation,

physician experience, available resources, and personnel

are all crucial factors in the decision making.[14] Immediate

involvement of an anesthetist and an otolaryngology

team is crucial.[15] Blind nasotracheal intubation should not

be attempted in patients with Ludwigs angina given the

potential for bleeding and abscess rupture.[4,14,15] Flexible

nasotracheal intubation requires skill and experience, if

not feasible, cricothyrotomy and tracheostomy under local

anesthesia are occasionally performed in the emergency

department in those with advanced stages of the

disease.[16] Elective awake tracheostomy is a safer and more

logical method of airway management in patients with a

fully developed Ludwigs angina.[17]

Tracheostomy using local anesthesia has been

considered the gold standard of airway management

in patients with deep neck infections, but it may be

difficult or impossible in advanced cases of infection

because of the position needed for tracheostomy

or because of anatomical distortion of the anterior

neck.[18-20]

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

Bansal A, Miskoff J, Lis RJ. Otolaryngologic critical care. Crit Care

Clin 2003;19:55-72.

Moreland LW, Corey J, McKenzie R. Ludwigs angina. Report of a

case and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 1988;148:461-6.

Spitalnic SJ, Sucov A. Ludwigs angina: Case report and review. J

Emerg Med 1995;13:499-503.

Fischmann GE, Graham BS. Ludwigs angina resulting from the

infection of an oral malignancy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1985;43:795-6.

Owens BM, Schuman NJ. Ludwigs angina. Gen Dent 1994;42:84-7.

Owens BM, Schuman NJ. Ludwigs angina: Historical perspective. J

Tenn Dent Assoc. 1993;73:19-21.

LeJeune HB, Amedee RG. A review of odontogenic infections. J La

State Med Soc 1994;146:239-41.

Finch RG, Snider GE Jr, Sprinkle PM. Ludwigs angina. JAMA

1980;243:1171-3.

Britt JC, Josephson GD, Gross CW. Ludwigs angina in the pediatric

population: Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr

Otorhinolaryngol 2000;52:79-87.

Har-El G, Aroesty JH, Shaha A, Lucente FE. Changing trends in deep

neck abscess. A retrospective study of 110 patients. Oral Surg Oral

Med Oral Pathol 1994;77:446-50.

Kurien M, Mathew J, Job A, Zachariah N. Ludwig's angina. Clin

Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1997;22:263-5.

Bross-Soriano D, Arrieta_Gmez JR, Prado-Calleros H, Schimelmitzldi J, Jorba-Basave S. Management of Ludwig's angina with small

neck incisions: 18 years experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg

2004;130:712-7.

Shockley WW. Ludwigs angina: A review of current airway

management. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;125:600.

Marple BF. Ludwigs angina: A review of current airway

management. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;125:596-9.

Neff SP, Merry AF, Anderson B. Airway management in Ludwigs

angina. Anaesth Intensive Care 1999;27:659-61.

Parhiscar A, Har-El G. Deep neck abscess: A retrospective study of

210 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2001;110:1051-4.

Irani BS, Martin-Hirsch D, Lannigan F. Infection of the neck spaces:

A present day complication. J Laryngol Otol 1992;106:455-8.

Sethi DS, Stanley RE. Deep neck abscesses changing trends. J

Laryngol Otol 1994;108:138-43.

Busch RF, Shah D. Ludwigs angina: Improved treatment.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;117:S172-5.

REFERENCES

How to cite this article: Candamourty R, Venkatachalam S, Ramesh

Babu MR, Kumar GS. Ludwig's angina - An emergency: A case report

with literature review. J Nat Sc Biol Med 2012;3:206-8.

1.

Source of Support: Nil. Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Saifeldeen K, Evans R. Ludwigs angina. Emerg Med J 2004;21:242-3.

Journal of Natural Science, Biology and Medicine | July 2012 | Vol 3 | Issue 2

208

You might also like

- 2020 Understanding Pathophysiology of Hemostasis Disorders in Critically Ill Patients PDFDocument4 pages2020 Understanding Pathophysiology of Hemostasis Disorders in Critically Ill Patients PDFMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- 2017 Dysphagia - Approach To Assessment and TreatmentDocument14 pages2017 Dysphagia - Approach To Assessment and TreatmentMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- 2017 Coffee Consumption and Health - Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Multiple Health OutcomesDocument18 pages2017 Coffee Consumption and Health - Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Multiple Health OutcomesMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of contraceptive methods review highlights hierarchy from sterilization to barriersDocument13 pagesEfficacy of contraceptive methods review highlights hierarchy from sterilization to barriersMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Pancreatitis Aguda Severa 2016Document12 pagesPancreatitis Aguda Severa 2016Cyliane AnscechiNo ratings yet

- 2016 Maternal Obesity As A Risk Factor For Caesarean SectionDocument6 pages2016 Maternal Obesity As A Risk Factor For Caesarean SectionMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Cuidados Diabetes 2016Document119 pagesCuidados Diabetes 2016Diego Pizarro ReyesNo ratings yet

- 2018 Glucocorticoid-Induced OsteoporosisDocument10 pages2018 Glucocorticoid-Induced OsteoporosisMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Dire StraitsDocument2 pagesDire StraitsMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- 2016 Psoriasis PDFDocument17 pages2016 Psoriasis PDFMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Gomes Wses 15Document6 pagesGomes Wses 15Rara Aulia IINo ratings yet

- 2016 Adverse Effects Associated With Proton Pump InhibitorsDocument3 pages2016 Adverse Effects Associated With Proton Pump InhibitorsMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- 2008 Classification and Management of Acute WoundsDocument5 pages2008 Classification and Management of Acute WoundsMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Types of Pancreatic CystsDocument1 pageTypes of Pancreatic CystsMaría Eugenia CondeNo ratings yet

- 2013 Management of Active Crohn DiseaseDocument9 pages2013 Management of Active Crohn DiseaseMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Types of Pancreatic CystsDocument1 pageTypes of Pancreatic CystsMaría Eugenia CondeNo ratings yet

- 2015 Digoxin-Associated Mortality.a Systematic ReviewDocument8 pages2015 Digoxin-Associated Mortality.a Systematic ReviewMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- 2016 CholangiopancreatosDocument13 pages2016 CholangiopancreatosMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Cuidados Diabetes 2016Document119 pagesCuidados Diabetes 2016Diego Pizarro ReyesNo ratings yet

- Ranking Iberoamericano 2012 de UniversidadesDocument24 pagesRanking Iberoamericano 2012 de UniversidadesJuan Sheput MooreNo ratings yet

- Practical Guide To The New Oral AnticoagulantsDocument3 pagesPractical Guide To The New Oral AnticoagulantsMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- UrolitiasisDocument98 pagesUrolitiasissstdocNo ratings yet

- 2015 Treatment of Lyme DiseaseDocument2 pages2015 Treatment of Lyme DiseaseMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Br. J. Anaesth. 2015 Frerk Bja - Aev371Document22 pagesBr. J. Anaesth. 2015 Frerk Bja - Aev371GitaPuspitasariNo ratings yet

- 2016 Diagnosis and Management of MenopauseDocument2 pages2016 Diagnosis and Management of MenopauseMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- JSC 160004Document22 pagesJSC 160004Veerawit TorsongneanNo ratings yet

- 2016 Therapeutic Advances in Localized Pancreatic CancerDocument7 pages2016 Therapeutic Advances in Localized Pancreatic CancerMiguel Angel Carrasco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Pancreatitis Aguda Severa 2016Document12 pagesPancreatitis Aguda Severa 2016Cyliane AnscechiNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Worksheets Section 1: Develop Quality Customer Service PracticesDocument3 pagesWorksheets Section 1: Develop Quality Customer Service PracticesTender Kitchen0% (1)

- Skripsi Tanpa Bab Pembahasan PDFDocument117 pagesSkripsi Tanpa Bab Pembahasan PDFArdi Dwi PutraNo ratings yet

- Back Order ProcessDocument11 pagesBack Order ProcessManiJyotiNo ratings yet

- Legion of Mary - Some Handbook ReflectionsDocument48 pagesLegion of Mary - Some Handbook Reflectionsivanmarcellinus100% (4)

- Gravity Warp Drive Support Docs PDFDocument143 pagesGravity Warp Drive Support Docs PDFKen WrightNo ratings yet

- Marketing NUTH fashion brand through influencers and offline storesDocument18 pagesMarketing NUTH fashion brand through influencers and offline storescandyNo ratings yet

- Bai Tap LonDocument10 pagesBai Tap LonMyNguyenNo ratings yet

- Advertising and Promotion An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective 11Th Edition Belch Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesAdvertising and Promotion An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective 11Th Edition Belch Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFjames.graven613100% (13)

- Existing culture of third-gender students influenced by social mediaDocument9 pagesExisting culture of third-gender students influenced by social mediaGilbert Gabrillo JoyosaNo ratings yet

- Qualitative data measurements are measurements of categorical variables and can be displayed as types. Qualitative data are non-numerical measurementsDocument22 pagesQualitative data measurements are measurements of categorical variables and can be displayed as types. Qualitative data are non-numerical measurementsnew rhondaldNo ratings yet

- Nstoklosa Resume 2Document2 pagesNstoklosa Resume 2api-412343369No ratings yet

- DCF ValuationDocument50 pagesDCF ValuationAnkit JainNo ratings yet

- RFQ for cat and dog food from Arbab TradersDocument2 pagesRFQ for cat and dog food from Arbab TradersAnas AltafNo ratings yet

- Ambj+6 1 5Document15 pagesAmbj+6 1 5samNo ratings yet

- Action Plan For My Long Term GoalsDocument4 pagesAction Plan For My Long Term Goalsapi-280095267No ratings yet

- Math 226 Differential Equation: Edgar B. Manubag, Ce, PHDDocument18 pagesMath 226 Differential Equation: Edgar B. Manubag, Ce, PHDJosh T CONLUNo ratings yet

- Being As Presence, Systemic ConsiderationsDocument34 pagesBeing As Presence, Systemic ConsiderationsJuan ortizNo ratings yet

- Designing Organizational Structure: Specialization and CoordinationDocument30 pagesDesigning Organizational Structure: Specialization and CoordinationUtkuNo ratings yet

- NafsDocument3 pagesNafsMabub_sddqNo ratings yet

- Gujarat State Eligibility Test: Gset SyllabusDocument6 pagesGujarat State Eligibility Test: Gset SyllabussomiyaNo ratings yet

- Word Wall Frys ListDocument10 pagesWord Wall Frys Listapi-348815804No ratings yet

- ScienceDocument112 pagesScienceAnkit JainNo ratings yet

- Moor defines computer ethics and its importanceDocument2 pagesMoor defines computer ethics and its importanceNadia MalikNo ratings yet

- Hughes explores loss of childhood faithDocument2 pagesHughes explores loss of childhood faithFearless713No ratings yet

- Taxation of RFCs and NFCs in PHDocument4 pagesTaxation of RFCs and NFCs in PHIris Grace Culata0% (1)

- Happy Birthday Lesson PlanDocument13 pagesHappy Birthday Lesson Planfirststepspoken kidsNo ratings yet

- 2015 International Qualifications UCA RecognitionDocument103 pages2015 International Qualifications UCA RecognitionRodica Ioana BandilaNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Alzheimer's Disease With Nursing ConsiderationsDocument10 pagesPathophysiology of Alzheimer's Disease With Nursing ConsiderationsTiger Knee100% (1)

- AI technologies improve HR analysisDocument4 pagesAI technologies improve HR analysisAtif KhanNo ratings yet

- Albelda - MechanicsDocument19 pagesAlbelda - MechanicsPrince SanjiNo ratings yet