Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Obesity TOG

Uploaded by

princessmeleana6499Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Obesity TOG

Uploaded by

princessmeleana6499Copyright:

Available Formats

TOG11_1_25-31-Stewart

24/12/08

The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist

04:20 PM

Page 25

10.1576/toag.11.1.25.27465 www.rcog.org.uk/togonline

2009;11:2531

Review

Review Obesity: impact on

obstetric practice and outcome

Authors Frances M Stewart / Jane E Ramsay / Ian A Greer

Key content:

Prepregnancy obesity is increasingly common.

More than half of all women who died from direct or indirect causes in the

200305 report, Saving Mothers Lives, were overweight or obese.

Obese mothers have an increased risk of complications.

Learning objectives:

To learn about the increased incidence of miscarriage, congenital malformation

and metabolic complications.

To learn about the increased risks of intrapartum complications.

Ethical issues:

Should medical assistance to conceive be withheld until BMI!35?

More of the healthcare budget should be spent on prevention rather than

treatment of obesity.

Keywords congenital abnormality / deep vein thrombosis / gestational diabetes

mellitus / hypertension / perinatal mortality

Please cite this article as: Stewart FM, Ramsay JE, Greer IA. Obesity: impact on obstetric practice and outcome . The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2009;11:2531.

Author details

Frances M Stewart MD MRCOG

Consultant, Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Antrim Area Hospital, Bush Road, Antrim,

County Antrim BT41 2RL, UK

Email: francesstewart1@hotmail.com

(corresponding author)

Jane E Ramsay MD MRCOG

Consultant in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Ayrshire Maternity Unit, Crosshouse Hospital,

Kilmarnock KA2 OBE, UK

2009 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Ian A Greer MD MRCP(UK) FRCP FRCPI FFFP

FMedSci FRCOG

Consultant in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Hull York Medical School, University of York,

Heslington,

York YO10 5DD, UK

25

TOG11_1_25-31-Stewart

24/12/08

Review

04:20 PM

Page 26

2009;11:2531

The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist

Introduction

The 200305 report of the Confidential Enquiries

into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom1

highlighted obesity as a significant risk for

maternal death. More than half of all women who

died from direct or indirect causes were either

overweight or obese.

For the mother, obesity increases the risk of

obstetric complications during the antenatal,

intrapartum and postnatal period, as well as

contributing to technical difficulties with fetal

assessment (Box 1). The offspring of obese mothers

also have a higher rate of perinatal morbidity and

an increased risk of long-term health problems.

The epidemiology of obesity

The prevalence of obesity, defined as a body mass

index (BMI) "30 kg/m2, has significantly increased

during the last three decades, both in the USA and

other countries in the developed world.American

trends are now seen among the European population.

In a health survey of England,2 the Department of

Health reported that 32% of women aged 3564 years

are overweight (BMI 2530) and 21% are obese

(BMI #30). In a British Womens Heart and Health

Study,3 one-quarter of the 4000 participants in

England, Scotland and Wales were found to be

clinically obese. One-fifth of the women were inactive

and two-fifths did not eat one portion of fresh fruit a

day. The Department of Health has predicted that, if

current trends continue, by 2010, 6 million women in

England will be obese.2 In line with this, a large

Scottish maternity hospital has observed a two-fold

increase in the proportion of women with a booking

BMI #30 over the last decade.4 Obesity amongst

women is of worldwide concern, as shown in

Australia by Callaway et al.5 in 2006. They noted that

35% of Australian women aged 2535 years were

overweight or obese. Obesity accounts for #280 000

deaths annually in the USA and will, if current trends

continue, soon overtake smoking as the primary

preventable cause of death.6

Antenatal health issues

Obesity is associated with an increased risk of first

trimester and recurrent miscarriage and fetal

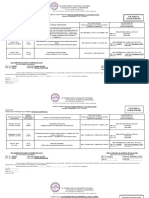

Box 1

Complications that are more

prevalent among obese women

before and during pregnancy

26

Prepregnancy

Menstrual disorders, infertility

Early pregnancy

Miscarriage, fetal anomalies, difficult and

less accurate ultrasound examination

Antenatal

Pregnancy-induced hypertension,

pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes,

venous thromboembolism

Intrapartum

Induction of labour, shoulder dystocia,

caesarean section, operative

anaesthetic difficulties

Postpartum

Haemorrhage, infection, venous

thromboembolism

Fetal

Macrosomia, fetal distress, perinatal

morbidity and mortality, birth injury

anomaly, in both women with polycystic ovary

syndrome and those with normal ovarian

morphology. A meta-analysis7 of 13 studies looking

at gonadotrophin-induced ovulation in women

with normogonadotrophic anovulatory infertility

found obesity and insulin resistance to be the most

clinically useful predicting factors for poor clinical

outcome. The incidence of spontaneous miscarriage

has been reported to rise as insulin resistance

increases.8 It has been suggested that insulinsensitising agents, such as metformin, also reduce

miscarriage rates.9 One potential mechanism for

this observation is an increased production of

inflammatory and prothrombotic agents produced

by adipose tissue or released from endothelium

secondary to stimulation by adipocyte-derived

factors. It has been suggested that plasminogen

activator inhibitor-type 1 (PAI-1) is associated with

increased rates of miscarriage in association with

maternal obesity. Treatment with metformin

appears to reduce PAI-1 and miscarriage rates.10,11

Several studies have shown up to a two-fold

increase in risk for neural tube defects where there

is prepregnancy maternal obesity. The greater the

maternal BMI, the higher the risk of congenital

malformation.12 It is well recognised that maternal

diabetes is a risk factor for the development of

congenital abnormality, including central nervous

system defects. A cumulative effect on the risk of

central nervous system birth defects when maternal

obesity and gestational diabetes coexist has also

been highlighted. Anderson et al.13 evaluated an

American population in a case control study

(n$477). After adjusting for maternal ethnicity,

age, education, smoking, alcohol use and

periconceptional vitamin use, obese women still

had substantially increased risks of delivering

offspring with anencephaly (odds ratio [OR] 2.3,

95% CI 1.24.3), spina bifida (OR 2.8, 95% CI

1.74.5) and isolated hydrocephaly (OR 2.7, 95%

CI 1.55.0). When gestational diabetes was

examined in isolation, the only anomaly seen more

frequently was holoprosencephaly.

The mechanisms that link obesity and congenital

anomaly are not fully understood. Several possible

hypotheses have been suggested, one being the

prevalence of undiagnosed type II diabetes or

significant insulin resistance without frank glucose

dysregulation. Epidemiological data from both the

USA and Europe have suggested that 3050% of

adults with type II diabetes are undiagnosed. Some

studies suggest that prepregnancy diagnosis of

diabetes may permit appropriate intervention prior

to conception and that obese women planning a

pregnancy should be screened and offered a highdose folic acid supplement. One could postulate

that weight reduction and tight glycaemic control

could help reduce the rates of congenital

abnormality in this high-risk group.

2009 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

TOG11_1_25-31-Stewart

24/12/08

04:20 PM

Page 27

The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist

Ultrasound and obesity

Obstetric ultrasound is widely practised

throughout the developed world. Initially, its major

indications were pregnancy dating and detection of

multiple pregnancy and fetal growth restriction.

With improved resolution the detection of fetal

anomaly has become possible. The limitations of

obstetric ultrasound as a screening test are dictated

by the expertise of the clinician, the quality of the

equipment and the habitus of the woman. By

absorbing the associated energy, adipose tissue can

significantly attenuate the ultrasound signal.

Therefore, a high-frequency, higher-resolution

signal would be more significantly absorbed at a

lesser depth, sacrificing image quality and depth of

field. A worrying consequence of maternal obesity,

consequently, is the reduced sensitivity of

ultrasound as a screening test for fetal anomaly. In

1990, Wolfe et al.14 examined the efficacy of

scanning the obese pregnant population. They

showed that scans performed on women with a

BMI greater than the 90th centile during the second

and third trimester had a 14.5% reduction in

visualisation of organs compared with lean women.

This reduction was most marked when visualising

the fetal heart, umbilical cord and spine.

Hypertension

Independent of pregnancy, hypertensive disorders

are more prevalent in obese women than in their

lean counterparts. Elevated prepregnancy BMI is an

independent risk factor for the development of

pregnancy-induced hypertension.15 Even when the

degree of excess body fat is moderate, the incidence

of hypertension and pre-eclampsia is significantly

higher in comparison with control patients.16 Most

published work suggests a two- to three-fold

increase in the risk of pre-eclampsia with a

BMI #30. Waist circumference has also been

reported to be a sensitive predictive marker of

possible pregnancy hypertensive complications.

Sattar et al.17 examined early pregnancy body

composition data from 1142 pregnant women.

Odds ratios were calculated for risk of hypertensive

complications of pregnancy in association with a

waist circumference #80 cm at %16 weeks of

gestation. The risk of pregnancy-induced

hypertension was approximately doubled (OR 1.8,

95% CI 1.12.9) and of pre-eclampsia tripled

(OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.16.8) in association with

central obesity.

OBrien et al.16 identified 13 cohort studies,

comprising nearly 1.4 million women. The risk of

pre-eclampsia typically doubled with each

57 kg/m2 increase in prepregnancy BMI. This

relationship persisted in studies that excluded

women with chronic hypertension, diabetes

mellitus and multiple gestation, or after

adjustment for other confounding factors. A recent

systematic review by Cnossen et al.18 aimed to

2009 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

2009;11:2531

Review

determine the accuracy of maternal BMI in

predicting pre-eclampsia and to explore the

clinical potential for selecting women for

treatment with low-dose aspirin. A total of 36

studies, testing 1 699 073 pregnant women (60 584

with pre-eclampsia) were included. They found

that among women with a BMI #35 as the only

risk, the incidence of pre-eclampsia was only 3%,

resulting in 714 women needing treatment to

prevent one case of pre-eclampsia. When a woman

with a BMI #35 also had other risk factors,

however, such as primigravidity or diabetes, the

risk was greatly elevated and the number needed to

treat in order to prevent one case of pre-eclampsia

was only 37.18 This is a very useful paper for clinical

practice and it highlights the importance of

holistic evaluation of risk at booking for antenatal

care. Most studies within the literature conclude

that pregnancies amongst the obese population

should be considered high risk and appropriate

antenatal care provided. The need for

prepregnancy counselling and advice for this

group of women is highlighted repeatedly.

The mechanism of effect

As stated, obesity is a risk factor for many maternal

obstetric complications, including pre-eclampsia

and gestational diabetes. The mechanisms involved

are complex but one possible unifying hypothesis is

that there may be a syndrome of insulin resistance,

low-grade inflammation, dyslipidaemia and an

alteration in systemic microvascular function. This

metabolic and vascular derangement mirrors that

of the metabolic syndrome observed among those

with coronary heart disease and/or diabetes,

particularly in later life. In a prospective study,

Stewart et al.19 demonstrated that obese women

have a pro-inflammatory phenotype, with

impaired microvascular function, from early in

pregnancy. In lean women, inflammatory features

were acquired in later pregnancy. The excessive

inflammatory burden seen in the obese pregnant

woman may fuel this process, explaining some of

the increased association of obesity with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes.

Gestational diabetes mellitus and obesity

Gestational diabetes mellitus affects about 5% of all

pregnancies.20 In the NICE consultation

document21 on diabetes and pregnancy, a BMI #30

is considered a risk factor for the development of

gestational diabetes. The policy has changed from

offering no screening for gestational diabetes

mellitus to targeted screening in the healthy

maternal population, using clinical risk factors

(Box 2).

Striking data from a large prospective populationbased Swedish study,22 which included 151 025

women, warns of the implications of

interpregnancy weight gain. This study shows that

27

TOG11_1_25-31-Stewart

24/12/08

Review

Box 2

Criteria meriting antenatal

screening for gestational diabetes21

04:20 PM

Page 28

2009;11:2531

BMI # 30

Previous gestational diabetes

Previous macrosomic baby "4.5 kg

Family history of diabetes (first-degree relative with type 1

diabetes)

Belonging to a high-risk ethnic group, including:

South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi)

Black Caribbean

Chinese

if an increase in maternal BMI of 12 units occurs

between pregnancies, the risk of gestational

diabetes rises by 2040%. If a woman weighs 63 kg

and is 1.65 m tall (BMI 23) and gains 3 kg before

her second pregnancy, her BMI rises by 1 unit and

her risk of gestational diabetes rises by #30%. If she

gains 6 kg and, therefore, becomes overweight

(gaining 2 BMI units), her risk of gestational

diabetes rises by 100%. If she becomes obese, her

risk of gestational diabetes rises by 200%.22

Effective treatment of gestational diabetes does

reduce the risk of macrosomia. Instrumental and

operative delivery rates, however, are increased even

in the absence of fetal macrosomia.23 Crowther

et al.24 conducted a randomised clinical trial to

determine whether treatment of women with

gestational diabetes mellitus reduced the risk of

perinatal complications. The rate of serious

perinatal complications was significantly lower

among the infants of subjects in the intervention

group than among the infants of the women in the

routine care group (1% versus 4%, P$0.01).24

If gestational diabetes mellitus is diagnosed, tight

metabolic control should be achieved through diet

and, when indicated, insulin therapy. Insulin

therapy is required more often in obese women

with gestational diabetes mellitus than in lean

women.25 Treatment using insulin reduces maternal

and fetal morbidity.26 Mothers who develop

gestational diabetes have a 50% higher risk of

developing diabetes during their lifetime27 and this

risk may be greatest in obese woman.28 For the

obese individual with gestational diabetes,

pregnancy offers an ideal opportunity to give them

future lifestyle advice in terms of exercise and

weight loss and, therefore, to reduce the potential

for vascular disease in the long term.

Intrapartum issues

Obesity and diabetes are independently associated

with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Rosenberg

et al.29 undertook a large population-based study.

Data were collected from the 1999, 2000 and 2001

New York City birth files for 329 988 singleton

births, containing information on prepregnancy

weight and antenatal weight gain. During

pregnancy, obese women are at increased risk of

several adverse perinatal outcomes, including

28

The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist

anaesthetic, perioperative and other maternal and

fetal complications.30 Obese women have higher

rates of induction of labour31 and failed induction

(7.9% versus 10.3% versus 14.6% with increasing

BMI).32 Caesarean section rates in nulliparous obese

women are higher than in lean women (20.7% in

the control group versus 33.8% in the obese group

and 47.4% in the morbidly obese group; P # 0.01).33

A higher rate of obstetric complications among

obese women has been reported, including

operative vaginal delivery (8.4% versus 11.4% and

17.3% with increasing BMI; P % 0.001), shoulder

dystocia (1% versus 1.8% and 1.9% with increasing

BMI; P % 0.021) and third/fourth-degree

lacerations (26.3% versus 27.5% and 30.8% with

increasing BMI; P % 0.001) compared with the

normal BMI group.32 The frequency of both elective

(8.5% versus 4%) and emergency caesarean section

(13.4% versus 7.8%) is almost doubled for very

obese women compared with the normal BMI

group.34 When other factors such as macrosomia,

nulliparity, induction or diabetes were accounted

for, maternal obesity was still found to influence the

mode of delivery independently.35 In another study

of 126 080 deliveries,36 after excluding women with

diabetes and hypertensive disease, there was a threefold increased risk of failure to progress in the first

stage and almost a trebling of caesarean section rate

from 10.8% to 27.8% (OR 3.2) among obese

women when compared with lean.

From the anaesthetic perspective, the risks of failed

epidurals, increased aspiration during general

anaesthesia and difficulty with intubation are the

most commonly cited compucations. Increased

rates of caesarean delivery, macrosomia, shoulder

dystocia, difficulty obtaining peripheral

intravenous access and inaccurate or difficult blood

pressure monitoring are also reported.37 Common

operative complications include loss of landmarks,

making vascular access difficult, and increased risk

of respiratory complications, such as aspiration and

pneumonitis. Increased retention of lipid-soluble

agents, increased drug distribution and more rapid

desaturation have also been reported.

The anaesthetist plays an important role in

preventing serious complications and must be

aware of the many potential hazards. Extra

vigilance is required to guide these women safely

through the perioperative period. There are very

few trials in the literature on the use of epidural and

spinal anaesthesia in the obese woman. Many case

reports exist on the difficulty of technique and

reductions in drug dosage requirements.

Postpartum issues

It is now recognised that adipose tissue produces a

variety of bioactive peptides, collectively termed

adipokines. Alteration of adipose tissue mass in

2009 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

TOG11_1_25-31-Stewart

24/12/08

04:20 PM

Page 29

The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist

obesity affects the production of most adiposesecreted factors: there is an increase in several

adipokines. Increased levels of angiotensinogen

have been implicated in hypertension; PAI-1 in

impaired fibrinolysis; and acylation-stimulating

protein, tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6

and resistin in insulin resistance.38 Pregnancy is a

prothrombotic state, secondary to an increase in

activity of coagulation factors XII, X and VIII, as

well as fibrinogen.39 In the puerperium, deep

venous thrombosis, endometritis, postpartum

haemorrhage, prolonged hospitalisation and

wound infection and dehiscence are also seen with

increased frequency in obese women.37

The leading cause of maternal mortality remains

venous thromboembolism and the postpartum

period is the time of greatest risk, secondary to

vascular damage at childbirth. The coagulation

cascade is activated by inflammatory cytokines

causing endothelial activation and this is further

increased with obesity. Several studies have shown

that obese patients have higher plasma

concentrations of all prothrombotic factors

(fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor [VWF] and

factor VII), compared with non-obese controls,

with a positive association with central fat.40 It has

been proposed that the secretion of interleukin-6

by adipose tissue, combined with the actions of

adipose tissue-expressed tumour necrosis factoralpha in obesity, could underlie the association of

insulin resistance with endothelial dysfunction,

coagulopathy and coronary heart disease.40

Implications for the fetus of

the obese mother

Short-term

Lower Apgar scores have been reported in the

neonates of obese mothers compared with those of

lean mothers.41 Prepregnancy BMI is a strong

positive predictor of birthweight. In fact, the odds

ratio for an obese mother delivering a large-fordates infant is 1.418.41 Macrosomia increases the

risk of shoulder dystocia, birth injury and the

incidence of low Apgar scores and perinatal death.

A recent 3-year retrospective analysis42 examined

the mode of delivery of infants weighing #4000 g.

The incidence of caesarean section among the

macrosomic group was 25.8%, compared with

13.1% (P%0.0001) for the general population

during the study period.

Infants born to obese mothers are more likely to

require admission to a neonatal intensive care unit

(NICU). In a retrospective study carried out in

France,43 the percentage of infants requiring

admission to a NICU was 3.5 times higher when

maternal obesity was present. The higher incidence

of diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes in the

obese population may contribute to this effect, with

2009 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

2009;11:2531

Review

an increased risk of neonatal admission to the NICU

for glycaemic control. The increased incidence of

macrosomia and consequent birth trauma may also

contribute to increased rates of perinatal morbidity

in the offspring of obese mothers.

One cohort study carried out in Denmark42

examined the relationship between maternal

prepregnancy BMI and the risk of stillbirth and

neonatal death. Maternal obesity was associated

with almost a three-fold increased risk of stillbirth

(OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.55.3) and neonatal death (OR

2.6, 95% CI 1.25.8) compared with women of

normal weight. Adjustment for maternal cigarette

smoking, alcohol and caffeine intake, maternal age,

height, parity, gender of the child, years of

schooling, working status and cohabitation with

the partner did not change the conclusions, nor did

exclusion of women with hypertensive disorders or

diabetes mellitus. No single cause of death

explained the higher mortality in children of obese

women but more stillbirths were either

unexplained intrauterine deaths or associated with

fetoplacental dysfunction among obese compared

with normal weight women.42

Long-term

Barkers hypothesis44 describes a theory of

intrauterine programming, which suggests that

babies who are small at birth or during infancy,

secondary to maternal starvation during

pregnancy, have increased rates of cardiovascular

disease and type 2 diabetes in adult life. Forsn

et al.45 examined the association between maternal

BMI and the risk of coronary heart disease in the

next generation. Men whose mothers had a high

BMI in pregnancy had an increased risk of

coronary heart disease. The highest death rates

were, therefore, in men who had a low birthweight

and a low placental weight but whose mothers had

a high BMI during pregnancy. The effects were

large and highly significant. While undernutrition

is uncommon in the developed world, obesity and

cardiovascular disease are common. The direct

effects of maternal obesity on fetal programming

are under-researched. The concept of fetal

programming being related to the quality of

nutrition, rather than the quantity, needs to be

addressed. One may hypothesise that, in addition to

maternal malnutrition secondary to famine,

malnutrition secondary to an inappropriate diet of

highly processed, high-fat food lacking in essential

vitamins and nutrients, i.e. the modern Western

diet, may contribute to long-term adult ill health of

offspring through fetal programming.

Cost implications

In 2000, a prospective study46 examined the cost of

care of 435 women seen consecutively within their

obstetric service. The average cost in terms of

29

TOG11_1_25-31-Stewart

Review

24/12/08

04:20 PM

Page 30

2009;11:2531

antenatal care and duration of hospital stay was five

times higher for women who had a higher

prepregnancy BMI compared with normal weight

controls and duration of hospital stay was 3.9 to

6.2fold higher among the overweight mothers.

The overall financial burden of obesity on the

National Health Service is difficult to determine. The

implications of rising rates of maternal obesity for

maternity services include increased medicalisation

of labour and delivery and greater pressure on

neonatal services and antenatal and postnatal beds.

Conclusion and

recommendations

It is essential that obstetricians have guidelines for

management of the obese woman. Obesity is a risk

factor for both gynaecological and obstetric

complications. A multidisciplinary approach to

management is necessary to decrease the risks of

morbidity and mortality. There are a number of

recommendations for clinical management prior to

and during pregnancy:

Provide prepregnancy counselling for morbidly

obese women (in primary care/subfertility/

recurrent miscarriage/diabetic clinics).

Consider high doses of folic acid (5 mg).

A healthy diet and exercise are important in

pregnancy: refer to a dietician, advise to avoid

excessive weight gain, consider screening for

diabetes.

Provide an early booking visit to plan pregnancy

management.

Prescribe low-dose aspirin in the presence of

additional clinical risk factors for pre-eclampsia.

Consider antenatal thromboprophylaxis if there

are additional clinical risk factors for venous

thromboembolic disease.

Recommend a detailed anomaly scan and serum

screening for congenital abnormality.

Consider glucose tolerance testing at 28 weeks,

with the potential for repeating it in later pregnancy.

This group of women requires both primary and

secondary care intervention if we are to limit or

even reverse the epidemic of obesity within Western

society.

References

1 Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health. Saving Mothers

Lives: Reviewing Maternal Deaths to Make Motherhood Safer

20032005. The Seventh Report of the Confidential Enquiries into

Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: CEMACH; 2007.

2 Department of Health. Health Survey for England 2002Latest Trends.

London: DH; 2003 [www.dh.gov.uk/en/PublicationsAndStatistics/

PublishedSurvey/HealthSurveyForEngland/HealthSurveyResults/

DH_4001334].

3 Lawlor DA, Bedford C, Taylor M, Ebrahim S. Geographical variation in

cardiovascular disease, risk factors, and their control in older women:

British Womens Heart and Health Study. J Epidemiol Community Health

2003;57:13440. doi:10.1136/jech.57.2.134

4 Kanagalingam MG, Forouhi NG, Greer IA, Sattar N. Changes in booking

body mass index over a decade: retrospective analysis from a Glasgow

Maternity Hospital. BJOG 2005;112:14313.

doi:10.1111/j.14710528.2005.00685.x

30

The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist

5 Callaway LK, Prins JB, Chang AM, McIntyre HD. The prevalence and

impact of overweight and obesity in an Australian obstetric population.

Med J Aust 2006;184:569.

6 Manson JE, Bassuk SS. Obesity in the United States: a fresh look at its

high toll. JAMA 2003;289:22930. doi:10.1001/jama.289.2.229

7 Mulders AG, Laven JS, Eijkemans MJ, Hughes EG, Fauser BC. Patient

predictors for outcome of gonadotrophin ovulation induction in women

with normogonadotrophic anovulatory infertility: a meta-analysis. Hum

Reprod Update 2003;9:42949. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmg035

8 Dale PO, Tanbo T, Haug E, Abyholm T. The impact of insulin resistance on

the outcome of ovulation induction with low-dose follicle stimulating

hormone in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod

1998;13:56770. doi:10.1093/humrep/13.3.567

9 Glueck CJ, Phillips H, Cameron D, Sieve-Smith L, Wang P. Continuing

metformin throughout pregnancy in women with polycystic ovary

syndrome appears to safely reduce first-trimester spontaneous abortion:

a pilot study. Fertil Steril 2001;75:4652.

doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(00)01666-6

10 Glueck CJ, Wang P, Goldenberg N, Sieve L. Pregnancy loss, polycystic

ovary syndrome, thrombophilia, hypofibrinolysis, enoxaparin, metformin.

Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2004;10:32334.

doi:10.1177/107602960401000404

11 Glueck CJ, Sieve L, Zhu B, Wang P. Plasminogen activator inhibitor

activity, 4G5G polymorphism of the plasminogen activator inhibitor 1

gene, and first-trimester miscarriage in women with polycystic ovary

syndrome. Metabolism 2006;55:34552.

doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2005.09.008

12 Martinez-Frias ML, Frias JP, Bermejo E, Rodriguez-Pinilla E, Prieto L, Frias

JL. Pre-gestational maternal body mass index predicts an increased risk

of congenital malformations in infants of mothers with gestational

diabetes. Diabet Med 2005;22:77581.

doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01492.x

13 Anderson JL, Waller DK, Canfield MA, Shaw GM, Watkins ML, Werler MM.

Maternal obesity, gestational diabetes, and central nervous system birth

defects. Epidemiology 2005;16:8792.

doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000147122.97061.bb

14 Wolfe HM, Sokol RJ, Martier SM, Zador IE. Maternal obesity: a potential

source of error in sonographic prenatal diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol

1990;76:33942.

15 Erez-Weiss I, Erez O, Shoham-Vardi I, Holcberg G, Mazor M. The

association between maternal obesity, glucose intolerance and

hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in nondiabetic pregnant women.

Hypertens Pregnancy 2005;24:125136. doi:10.1081/PRG-200059853

16 OBrien TE, Ray JG, Chan WS. Maternal body mass index and the risk of

preeclampsia: a systematic overview. Epidemiology 2003;14:36874.

doi:10.1097/00001648-200305000-00020

17 Sattar N, Clark P, Holmes A, Lean ME, Walker I, Greer IA. Antenatal waist

circumference and hypertension risk. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:26871.

doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(00)01136-4

18 Cnossen JS, Leeflang MM, de Hann, Mol BW, Van der Post JA, Khan KS,

et al. Accuracy of body mass index in predicting pre eclampsia; bivariate

meta-analysis. BJOG 2007;114:147785.

doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01483.x

19 Stewart FM, Freeman DJ, Ramsay JE, Greer IA, Caslake M, Ferrell WR.

Longitudinal assessment of maternal endothelial function and markers of

inflammation and placental function throughout pregnancy in lean and

obese mothers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:969-75.

doi:10.1210/jc.2006-2083

20 Cypryk K, Pertynska-Marczewska M, Szymczak W, Zawodniak-Szalapska

M, Wilczynski J, Lewinski A. [Overweight and obesity as common risk

factors for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), perinatal macrosomy in

offspring and type-2 diabetes in mothers.] Przegl Lek 2005;62:3841.

21 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Diabetes in

Pregnancy: Management of Diabetes and its Complications from Preconception to the Postnatal Period. NICE Clinical Guideline 63. London:

NICE; 2008 [www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG63].

22 Villamor E, Cnattingius S. Interpregnancy weight change and risk of

adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Lancet

2006;368:116470. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69473-7

23 Sermer M, Naylor CD, Farine D, Kenshole AB, Ritchie JW, Gare DJ, et al.

The Toronto Tri-Hospital Gestational Diabetes Project. A preliminary

review. Diabetes Care 1998;21 Suppl 2:B3342.

24 Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS.

Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy

outcomes. N Engl J Med 2005;352:247786.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa042973

25 Comtois R, Sguin MC, Aris-Jilwan N, Couturier M, Beauregard H.

Comparison of obese and non-obese patients with gestational diabetes.

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1993;17:6058.

26 Langer O, Rodriguez DA, Xenakis EM, McFarland MB, Berkus MD,

Arrendondo F. Intensified versus conventional management of

gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;170:103646.

27 Linn Y, Barkeling B, Rssner S. Natural course of gestational diabetes

mellitus: long term follow up of women in the SPAWN study. BJOG

2002;109:122731. doi:10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.01373.x

28 Schranz AG, Savona-Ventura C. Long-term significance of gestational

carbohydrate intolerance: a longitudinal study. Exp Clin Endocrinol

Diabetes 2002;110:21922. doi:10.1055/s-2002-33070

29 Rosenberg TJ, Garbers S, Lipkind H, Chiasson MA. Maternal obesity and

diabetes as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes: differences

among 4 racial/ethnic groups. Am J Public Health 2005;95:154551.

doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.065680

2009 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

TOG11_1_25-31-Stewart

24/12/08

04:20 PM

Page 31

The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist

30 Perlow JH, Morgan MA. Massive maternal obesity and perioperative

caesarean morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;170:5605.

31 Usha Kiran TS, Hemmadis S, Bethel J, Evans J. Outcome of pregnancy in

a woman with an increased body mass index. BJOG 2005;112:76872.

doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00546.x

32 Kabiru W, Raynor BD. Obstetric outcomes associated with increase in

BMI category during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:92832.

doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.051

33 Weiss JL, Malone FD, Emig D, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, et al.

Obesity, obstetric complications and caesarean delivery ratesa

population based screening study. Am J Obstet Gynaecol

2004;190:10917. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.058

34 Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris JP, Wadsworth J, Joffe M, Beard RW, et al.

Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcomes; A study of 287 213 women in

London. Int J Obes Relat Disord 2001;25:117582.

doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801670

35 Ehrenberg HM, Durnwald CP, Catalano P, Mercer BM. The influence of

obesity and diabetes on the risk of caesarean delivery. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2004;191:96974. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.057

36 Sheiner E, Levy A, Menes TS, Silverberg D, Katz M, Mazor M. Maternal

obesity as an independent risk factor for caesrean section delivery.

Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2004;18:196201.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00557.x

37 Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Johansson A, Cnattingius S. Maternal

weight, pregnancy weight gain, and the risk of antepartum stillbirth. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:4639. doi:10.1067/mob.2001.109591

2009 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

2009;11:2531

Review

38 Guerre-Millo M. Adipose tissue and adipokines: for better or

worse. Diabetes Metab 2004;30:1319.

doi:10.1016/ S1262-3636(07)70084-8

39 Hellgren M, Blomback M. Studies on blood coagulation and fibrinolysis in

pregnancy, during delivery and in the puerperium. I. Normal condition.

Gynecol Obstet Invest 1981;12:14154.

40 De Pergola G, Pannacciulli N. Coagulation and fibrinolysis abnormalities

in obesity. J Endocrinol Invest 2002;25:899904.

41 Edwards LE, Hellerstedt WL, Alton IR, Story M, Himes JH. Pregnancy

complications and birth outcomes in obese and normal-weight women:

effects of gestational weight change. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:38994.

doi:10.1016/0029-7844(95)00446-7

42 Kristensen J, Vestergaard M, Wisborg K, Kesmodel U, Secher NJ. Prepregnancy weight and the risk of stillbirth and neonatal death. BJOG

2005;112:4038. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00437.x

43 Galtier-Dereure F, Montpeyroux F, Boulot P, Bringer J, Jaffiol C. Weight

excess before pregnancy: complications and cost. Int J Obes Relat

Metab Disord 1995;19:4438.

44 Barker DJ, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, Harding JE, Owens JA, Robinson

JS. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet

1993;341:938-41. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)91224-A

45 Forsn T, Eriksson JG, Tuomilehto J, Teramo K, Osmond C, Barker DJ.

Mothers weight in pregnancy and coronary heart disease in a cohort of

Finnish men: follow up study. BMJ 1997;315:83740.

46 Galtier-Dereure F, Boegner C, Bringer J. Obesity and pregnancy:

complications and cost. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71 Suppl 5:1242S8S.

31

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 101 Questions To Ask About Your LifeDocument18 pages101 Questions To Ask About Your LifeKika Spacey RatmNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- MCQ'S FOR Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument330 pagesMCQ'S FOR Obstetrics and Gynaecologywhoosh200887% (108)

- Mcqs For Mrcog Part 1 - Richard de CourcyDocument118 pagesMcqs For Mrcog Part 1 - Richard de Courcyprincessmeleana6499No ratings yet

- 29 - Abnormal Uterine ActionDocument31 pages29 - Abnormal Uterine Actiondr_asaleh94% (18)

- Pathophysiology of Incomplete Abortion: Risk Factors and ManagementDocument3 pagesPathophysiology of Incomplete Abortion: Risk Factors and ManagementClaire Nimor Ventulan50% (4)

- Doh Health Programs (Maternal)Document47 pagesDoh Health Programs (Maternal)Wilma Nierva Beralde100% (1)

- Unit I - Introduction-to-Midwifery-Obstetrical-NursingDocument43 pagesUnit I - Introduction-to-Midwifery-Obstetrical-NursingN. Siva100% (8)

- Legal MandatesDocument39 pagesLegal MandatesMarkGuirhem100% (1)

- C-S & VbacDocument54 pagesC-S & VbacDagnachew kasayeNo ratings yet

- FSRH Ukmec Full Book 2017Document178 pagesFSRH Ukmec Full Book 2017A KNo ratings yet

- 10 Things Every Physician Needs To Know About BurnoutDocument5 pages10 Things Every Physician Needs To Know About Burnoutprincessmeleana6499No ratings yet

- AsthmaDocument5 pagesAsthmaprincessmeleana6499No ratings yet

- OHSSDocument5 pagesOHSSprincessmeleana6499No ratings yet

- Tog 12091Document4 pagesTog 12091princessmeleana6499No ratings yet

- BoulderIng For BeginnersDocument42 pagesBoulderIng For BeginnersmeersonNo ratings yet

- Rules of The Road Eng PDFDocument264 pagesRules of The Road Eng PDFprincessmeleana6499No ratings yet

- Mirena Jaydess Differentiation Booklet Sept15Document12 pagesMirena Jaydess Differentiation Booklet Sept15princessmeleana6499No ratings yet

- LR ProtocolDocument159 pagesLR ProtocolJeevan VelanNo ratings yet

- Trial LabourDocument3 pagesTrial Laboursujinaranamagar18No ratings yet

- Partograph: (Use This Form For Monitoring Active Labour)Document1 pagePartograph: (Use This Form For Monitoring Active Labour)Omar Khalif Amad PendatunNo ratings yet

- Course Information For Current Semester/Term: Maklumat Kursus Untuk Semester/Penggal SemasaDocument5 pagesCourse Information For Current Semester/Term: Maklumat Kursus Untuk Semester/Penggal SemasaNurul IrhamnaNo ratings yet

- Gestational Trophoblastic DiseaseDocument22 pagesGestational Trophoblastic DiseaseBright KumwendaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Teenage Pregnancy On Maternal, Fetal and Neonatal OutcomesDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Teenage Pregnancy On Maternal, Fetal and Neonatal Outcomesjacque najeraNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Pemberian Aromaterapi Lemon (Citrus Lemon) Terhadap Mual Muntah Pada Ibu Hamil Trimester IDocument7 pagesPengaruh Pemberian Aromaterapi Lemon (Citrus Lemon) Terhadap Mual Muntah Pada Ibu Hamil Trimester IMei SuriyatiNo ratings yet

- Pregnant Teen Case ManagementDocument22 pagesPregnant Teen Case Managementapi-171781702100% (1)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Module 1 Hevinkumar PatelDocument12 pagesObstetrics and Gynecology Module 1 Hevinkumar PatelhevinpatelNo ratings yet

- Klasifikasi Plasenta PDFDocument9 pagesKlasifikasi Plasenta PDFTedi MulyanaNo ratings yet

- Preterm Rupture of MembranesDocument13 pagesPreterm Rupture of Membranesjoyrena ochondraNo ratings yet

- Association of Third Trimester Body Mass Index and Pregnancy Weight Gain in Obese Pregnant Women To Umbilical Artery Atherosclerotic Markers and Fetal OutcomesDocument7 pagesAssociation of Third Trimester Body Mass Index and Pregnancy Weight Gain in Obese Pregnant Women To Umbilical Artery Atherosclerotic Markers and Fetal OutcomesMahida El shafiNo ratings yet

- Sample PRC RequirementsDocument4 pagesSample PRC RequirementsRodney Beltran SubaranNo ratings yet

- Water Birth: Benefits and SafetyDocument21 pagesWater Birth: Benefits and SafetyudupisonyNo ratings yet

- Clinical Embryology (CH 1-7) (KLM) : TrisomyDocument4 pagesClinical Embryology (CH 1-7) (KLM) : Trisomykamran_zarrarNo ratings yet

- Prophylactic Cervical Cerclage (Modified Shirodkar Operation) For Twin and Triplet Pregnancies After Fertility TreatmentDocument8 pagesProphylactic Cervical Cerclage (Modified Shirodkar Operation) For Twin and Triplet Pregnancies After Fertility TreatmentAiraNo ratings yet

- Maternal and Child HealthDocument15 pagesMaternal and Child Healthgamal attamNo ratings yet

- Molar PregnancyDocument15 pagesMolar Pregnancyapi-3705046No ratings yet

- Retained PlacentaDocument2 pagesRetained PlacentaAmiraah MasriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Kukerta Terintegrasi AbdimasDocument5 pagesJurnal Kukerta Terintegrasi AbdimasholaNo ratings yet

- Keep Calm and Wait for Labor: Why Going to Full Term Is Best for Mom and BabyDocument1 pageKeep Calm and Wait for Labor: Why Going to Full Term Is Best for Mom and BabyGururaj kulkarniNo ratings yet

- PPH Guideline 2015Document87 pagesPPH Guideline 2015Diksha chaudharyNo ratings yet

- Tabel JurnalDocument31 pagesTabel JurnalAlfNo ratings yet