Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Operant Conditioning in The Common Crow

Uploaded by

sborgeltOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Operant Conditioning in The Common Crow

Uploaded by

sborgeltCopyright:

Available Formats

OPERANT CONDITIONING IN THE COMMON CROW

(CORVUS BRACHYRHYNCHOS)

ROBERT W. POWELL

CRowsare characterizedby their resourcefulness, adaptabilityto diverse

habitats,and extensivebehavioralrepertoire(Peterson,1963). They live

in well-organizedsocialgroupsand seemto possessa complexlanguage

(Lorenz, 1952; Fringsand Frings, 1959; Bannerman,1963; Chamberlain

and Cornwell,1971). Extraordinarylearningcapabilitiesare oftenattrib-

uted to the crow,but evidenceof this is primarily anecdotal.Surprisingly

few experimentalstudieshave been conductedwith crows. In the only

contemporaryreport of this type, two crows (incorrectly identified as

Corvusamericanus)showeda progressive decrease

in errorsto criterionon

multiple reversalsof a visual discriminationproblem (Stettner et al., 1966).

While their performanceseemedsuperiorto that of pigeonsstudiedunder

similar conditions,generalizationsare limited by the small number of

subjectsand the brief duration of the experimentoccasioned by the pre-

mature death of both birds.

The presentexperimentwas conductedto study the developmentand

maintenanceof operantrespondingin crows,underbasicschedules of food

reinforcement.Operantconditioningis concerned primarily with responses

that have immediateconsequences for the subject,suchas deliveryof food

(positive reinforcement),removalof noxiousstimuli (negative reinforce-

ment), or the deliveryof noxiousstimuli (punishment).

Schedulesof reinforcementinvolve various contingenciesbetween be-

havior and its consequences. Several examplesare: Reinforcementfor

every response(continuousschedule),reinforcementfor the first response

after 1 minute since the last reinforcement (fixed-interval schedule),

reinforcementfor the first responseafter sometime period which varies

unsystematically(variable-intervalschedule).

/[ETII ODS

Five adult Common Crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) were maintained at approxi-

mately 80 percent of their normal weight. Three of the crows (C1, C3o, C45) were

shaped to key-peck for food reinforcement (Skinner, 1951). Shaping involves rein-

forcement of successiveapproximationsof the desired response.For example, as key-

pecking was the desired responsethe bird was first reinforced (rewarded with food)

for facing toward the key, then for standing in front of the key, and finally for

pecking the key. The other birds (C2, C3) were trained through an auto-shaping

procedure (Brown and Jenkins, 1968) in which momentary illumination of the key

was followed by food presentation. This resulted in reliable aquisition of key-pecking

in pigeons. Gaines Prime (beef variety) was used for reinforcement, and this seemed

to be critical. Attempts to train the birds using either mixed grain or dried dog food

738 The Auk, 89: 738-742. October 1972

October 1972] Crow Operant Conditioning 739

TABLE 1

MEAN RESPONSE

RATES DURING TItE LAST FIVE SESSIONS]FOREAC CROW, IJNDER

THE FINAL TWO VALUES OF EACH SCHEDIJLETO VIIICH TI-IE BIRD VAs EXPOSED

1

Re- Re- Re-

Cumu- sponses Cumu- sponses Cumu- sponses

lative per lative per lative per

Sub- Sched- ses- min- Sched- ses- min- Sched- ses- min-

ject ule sions ute ule sions ute ule sions ute

C1 FR-75 69 51.6 VI-30 21 44.1

FR-100 82 49.2 VI-60 32 48.4

C2 VI-60 28 45.1 FR-66 65 36.2 FI-60 35 19.9

VI-120 39 43.6 FR-100 79 30.0 FR-120 51 16.2

C3 VI-60 29 37.6 VR-?5 36 57.4

VI-120 46 41.5 VR-100 57 38.4

C30 VR-50 46 89.4 FI-120 47 9.5

VR-75 70 91.2 FI-240 68 3.5

C45 FR-40 62 51.7 VR-?5 36 69.7 FI-60 33 6.8

FR-50 81 43.7 VR-100 52 62.5 FI-120 52 9.0

The sequenceof schedulesis indicatedfrom left to right, respectively. Cumulativesessions

indicates

the numberof experimentalsessions completedup to that time.

(Ken-L-Ration Biskit) for reinforcement were unsuccessful. Reinforcement times

ranged from 3.0 to 5.0 seconds. A standard pigeon test chamber (Lehigh Valley,

Model 1519C) was used. The hopperwas enlargedand modified so that food could

not be. obtained when the hopper was down. These modifications were necessitated

by the largebill of the crowcomparedto the pigeon's.

Each crow was studied as schedulerequirementswere gradually extended. A

differentkey light colorwas associatedwith eachschedule.The sequence of schedules

and mean responserates for each bird are presentedin Table 1. Mean responserates

were determinedby dividing the total number of responsesby the total time less the

reinforcementtime. Each schedulerequirement remained in effect until performance

stabilized. Stability was judged through inspectionof cumulative responserecords

and consistencyin response rates between sessions. The duration of experimental

sessionsranged from 30 minutes to 2 hours, with sessionlength increasing as the

schedulerequirementincreased.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Figure 1 showsrepresentativecumulativeresponsere.co.rds for the three

crowsstudiedunder each schedule.Under fixed ratio (FR) schedules,in

the presenceof a whitekey light, the nth key-peckresultedin.accessto food.

Each crowshowedconsistentpausingafter reinforcementand then a steady

rate of respondinguntil the next reinforcementwas obtained. This is char-

acterizedas a break and run pattern and is typical of behaviorunder FR

schedules (Fersterand Skinner,1957). A consistent directrelationshiphas

beenfoundbetweenpostreinforcement pausedurationand the ratio response

requirement(Felton and Lyon, 1966; Powell, 1968). Quantitativeanalysis

of the presentdata showeda similar direct relationshipfor the crow. The

meanpausedurationsin secondsat the last two schedulerequirementswere

740 ROBERTW. POW,L [Auk, Vol. 89

CROW 1 FR-100

CROW 2

]Vi.3ROW

Vl-6

Vl-60 CROW 2 V1-120

CROW 45

Vl-60 CROW 3 V1-120

FR-20 FR-50

VR-50 CROW 3 VR-100

CROW 2

FI-60

'' / 1-2o

CROW 30

VR-25 CROW

30 VR-50

FI-240

/ CROW 45

VR-50 CROW 45 VR-100

FI-60 F1-120

I 25MINUTES

I

Figure 1. Cumulative responserecordsshowing representativeperformance for each

crow studied under the four schedulesof reinforcement. Slash marks indicate the pre-

sentation of food reinforcement.

October 1972] Crow Operant Conditioning 741

a.sfollows: Crow 1, FR-75 (37.9), FR-100 (50.8); crow2, FR-66 (37.6),

FR-100 (78.7); crow 45, FR-40 (25.6), FR-50 (33.6).

The variable interval (VI) scheduleswere associatedwith a red key

light. Undertheseschedules, the first key-peckafter a specifiedintervalof

time elapsedproducesfood reinforcement.The duration of eachsuccessive

intervalvaries,with the overallschedulerequirementidentifiedby the mean

of the intervals,i.e. 30 seconds,60 seconds.The cumulativeresponserec-

ordsin Figure 1 showvery consistentrespondingunder the VI schedules.

Discerniblepausesrarelyoccurred.Mean response ratesunderthe VI and

FR schedules did differ substantially,and local response rateswere much

higher under the FR schedulesas shownby the slope of the response

records.

The variableratio (VR) schedules were signalledby a greenkey light.

Under theseschedules, the nth key-peck,on the average,was reinforced

with food. The resultsin Table 1 show that the VR schedulesgenerally

producedthe highestratesof responseof the schedules studiedhere. The

cumulativeresponserecordsin Figure 1 show fairly consistentresponding

with high local rates. Pausing,particularly after reinforcement,was not

uncommon.Inspectionof response recordssuggests that postreinforcement

pausesincreasedin frequencyand durationwith increases in the schedule

requirement.Thus in severalrespectsrespondingunder the VR schedules

was moreanalogousto.FR than VI behaviorin the crow.

The fixed interval (FI) schedules were signalledby a red key light, as

were the VI schedules.Only crow 2 was studiedunder both VI and FI

schedules,the first key-peckafter a fixed periodof time resultedin food

reinforcement.Response ratesunderthe FI schedules werethelowestby far

of any schedulestudied. The cumulativeresponserecordsin Figure 1 show

that FI behaviorwas characterizedby a break and run pattern of response.

The crow typically pausedfor long periodsfollowingreinforcement,and

then respondedsteadily until the next reinforcementwas obtained. Grad-

ually acceleratedrespondingoccurredmuchlessfrequentlythan the break

and run pattern.

The mostimportantresultof this experimentwasthe reliablecontrolof

responding in the crowthroughstandardoperantconditioningprocedures.

Responding waseffectivelymaintainedundereachof the basicschedules of

reinforcement and terminalpatternsof responsewerevery similarto other

speciesthat havebeenstudiedundertheseschedules.

Exceptfor minorapparatusmodifications, we usedthe sameexperimental

proceduresfor crowsas are gefaerallyemployedwith pigeons.

The systematicrelationshipsthat have been observedbetweenbehavior

and the scheduleof reinforcementare extendedby the present results.

Thesedata clearly showthat the CommonCrow can be usefullyemployed

742 l{oEar W. PowEzz [Auk, Vol. 89

as an experimentalsubject. Perhapsof greatestimportancein this respect,

variouscharacteristics

of the speciessuchas language,socialrelationships,

capacityfor learning,and sensorycapabilitiesbecameaccessible to study

throughobjectiveexperimentalprocedures.

SUMMARY

Five CommonCrowswere trained to key-peck for food reinforcement.

Three crows each were then studied under four intermittent schedules of

reinforcement:Fixed ratio, variableinterval, variable ratio, and fixed

interval. Consistentrespondingwas maintainedin all birds as schedule

requirementswere gradually extendedto substantialvalues. Similar re-

sponsepatterns developedfor each of the three crows under the same

scheduleof reinforcement.The behaviorof the crowswas comparableto

that of pigeons(Ferster and Skinner,1957), rats (Appel, 1964; Miller and

Ackley, 1970), and monkeys(Hake. et al., 1967; Hodosand Trumbule,

1967).

LITERATURE CITED

APPEn,J.B. 1964. The rat: an importantsubject.J. Exp. Anal. Behav.,7: 355-356.

BAnNERsrAN, D.A. 1953. The birds of the British Isles. Edinburgh,Oliver and Boyd.

BROWN,P. L., ANDH. 3I. JEnxns. 1968. Auto-shapingof the pigeon'skey peck.

J. Exp. Anal. Behav.,11: 1-8.

CAmEAIN, D. W., AND G. W. COtnWLL. 1971. Selectedvocalizationsof the

CommonCrow. Auk, 88: 613-634.

FEnTOn,M., ANDD. O. LYON. 1966. The post-reinforcementpause. J. Exp. Anal.

Behav., 9: 131-134.

FERSTER,C. B., An) B. F. SxrntR. 1957. Schedulesof reinforcement. New York,

Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Fnvs, H., Am) M. Frs. 1959. The language of crows. Sci. Amer., 201: 119-131.

HAX, D. F., N.H. Azure, AnD R. Oxom). 1967. The effect of punishment intensity

on squirrel monkeys. J. Exp. Anal. Behav., 10: 95-107.

Hoos, W., An) G. H. Tu:run. 1967. Strategies of schedule preference in chim-

panzees.J. Exp. Anal. Behar., 10: 503-514.

Lorenz, K. Z. 1952. King Solomon'sring: new light on animal ways. New York,

Crowell.

MinnR, L., Anp R. AcKn. 1970. Summation of responding maintained by fixed

interval schedules.J. Exp. Anal. Behar., 13: 199-203.

PEtErson, R.T. 1963. The birds. New York, Time, Inc.

PowEnn, R.W. 1968. The effect of small sequentialchangesin fixed-ratio size upon

the post-reinforcementpause. J. Exp. Anal. Behav., 11: 589-593.

Sxn, B.F. 1951. How to teach animals. Sci. Amer., 185: 26-29.

SrETnE, L. J., K. MArYnx, AnDJ. 3I. BRAn). 1966. Habit reversalin the crow,

Corvus amer{canus.PsychonomicSci., 4: 331-332.

Department of BehavioralScience,University of South Florida, Tampa,

Florida SS620. Accepted10 August 1971.

You might also like

- Multimedia Audio or Video Lesson Idea Template2022Document3 pagesMultimedia Audio or Video Lesson Idea Template2022api-619251533No ratings yet

- Pro Life Spiritualism - Robert BayerDocument69 pagesPro Life Spiritualism - Robert BayerAnthony EdwardsNo ratings yet

- GUTbiomin FinalwfigsDocument11 pagesGUTbiomin Finalwfigsrio22No ratings yet

- Hitchhiker's Guide To Magnetism (Script MoskowitzDocument48 pagesHitchhiker's Guide To Magnetism (Script MoskowitzWauzi2000No ratings yet

- Voice RecognitionDocument3 pagesVoice RecognitionSimon Benjamin100% (1)

- Eleonor WhiteDocument64 pagesEleonor WhiteSimon BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Mental Workload of Cognitive Tasks in Virtual Reality Using EOG Eye Tracker and EEG SignalsDocument16 pagesEvaluation Mental Workload of Cognitive Tasks in Virtual Reality Using EOG Eye Tracker and EEG SignalsJ Andrés SalasNo ratings yet

- GBPPR Active Denial SystemDocument30 pagesGBPPR Active Denial SystemRobert EckardtNo ratings yet

- Technobeam User Manual IDocument164 pagesTechnobeam User Manual ILucia GeraldoNo ratings yet

- WWW Citizensaht Org Implant TechDocument30 pagesWWW Citizensaht Org Implant TechLazlo JoószNo ratings yet

- Buck, Jirah D - Modern World MovementsDocument228 pagesBuck, Jirah D - Modern World MovementsXangot100% (1)

- GBPPR 'Zine - Issue #62Document76 pagesGBPPR 'Zine - Issue #62GBPPRNo ratings yet

- Strahlenfolter Stalking - TI - Robert O. Butner - Account From Mr. Joseph HohlmanDocument16 pagesStrahlenfolter Stalking - TI - Robert O. Butner - Account From Mr. Joseph HohlmanHans-Werner-Gaertner100% (1)

- Service Bulletin: 2008 Civic Sedan, Coupe: PDI and New Model InformationDocument7 pagesService Bulletin: 2008 Civic Sedan, Coupe: PDI and New Model InformationCarlos100% (1)

- Bio ElectromagneticDocument121 pagesBio Electromagneticdwi sujadirNo ratings yet

- Christian Interpretations of Ham's CurseDocument3 pagesChristian Interpretations of Ham's CurseΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Messy Minds PDFDocument104 pagesMessy Minds PDFJose LuizNo ratings yet

- Strahlenfolter Stalking - TI - Sharon Rose - Ramblings of A Targeted Individual - Sharonpoet-Ti - Blogspot.deDocument11 pagesStrahlenfolter Stalking - TI - Sharon Rose - Ramblings of A Targeted Individual - Sharonpoet-Ti - Blogspot.deKarl-Hans-RohnNo ratings yet

- 1984 Argument EssayDocument6 pages1984 Argument Essayapi-358956677No ratings yet

- Pictish Stones Builders and WorshippersDocument8 pagesPictish Stones Builders and WorshippersDaryl PenningtonNo ratings yet

- User's Manual For The OTA-710CDocument37 pagesUser's Manual For The OTA-710CHoa PhanNo ratings yet

- Rare Photographs IndiaDocument30 pagesRare Photographs IndiaSwaminathan AdaikkappanNo ratings yet

- Nanotech BadDocument106 pagesNanotech BadMason OwenNo ratings yet

- PDF Roboics1Document65 pagesPDF Roboics1Sai Krishna TejaNo ratings yet

- SpeedtouchmanualDocument100 pagesSpeedtouchmanualjoelNo ratings yet

- X - NG - Jack Kerouac, On The Nobody Again - Paranormal - 4chanDocument34 pagesX - NG - Jack Kerouac, On The Nobody Again - Paranormal - 4chanAnonymous dIjB7XD8ZNo ratings yet

- Strahlenfolter Stalking - TI - Mind Control, Electronic Attack, Unusual, Strange Device TypesDocument31 pagesStrahlenfolter Stalking - TI - Mind Control, Electronic Attack, Unusual, Strange Device TypesWirklichkeit-kommtNo ratings yet

- Microwave Congruence SchizophreniaDocument27 pagesMicrowave Congruence SchizophreniaSimon BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Strahlenfolter - Electronic Harassment - Neural Implants - Past, Present & Future PART1Document11 pagesStrahlenfolter - Electronic Harassment - Neural Implants - Past, Present & Future PART1nwo-mengele-doctorsNo ratings yet

- Maglev Train: Magnetic Levitation and Types of Maglev TrainsDocument7 pagesMaglev Train: Magnetic Levitation and Types of Maglev TrainsGaneshNo ratings yet

- Rare PicsDocument30 pagesRare PicsHarcharan Singh Marwah100% (1)

- RfidDocument3 pagesRfidRangaprasad NallapaneniNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Beam Ray MachineDocument6 pagesAnalysis of Beam Ray Machinetheodorakis017781No ratings yet

- Essay - Mind Control and ManipulationDocument3 pagesEssay - Mind Control and ManipulationFelicia Cristina CotrauNo ratings yet

- EMC HondaDocument15 pagesEMC HondaChương Phan ĐứcNo ratings yet

- The Top Ten Largest Databases in The WorldDocument8 pagesThe Top Ten Largest Databases in The Worldlewis_kellerNo ratings yet

- Short Detail of RNM UserDocument2 pagesShort Detail of RNM UserKunalNo ratings yet

- YB-ALD Installation InstructionsDocument2 pagesYB-ALD Installation InstructionsMustansir BandukwalaNo ratings yet

- Patent 060606 International StatusDocument2 pagesPatent 060606 International StatusJuanNo ratings yet

- RAPTOR RXi Countersurveillance ReceiverDocument6 pagesRAPTOR RXi Countersurveillance ReceiverSimon BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Goldilocks User ManualDocument24 pagesGoldilocks User ManualcoolboyNo ratings yet

- Table Des Matieres 200 Articles Gang Stalking Belgium B Simon LinkedDocument24 pagesTable Des Matieres 200 Articles Gang Stalking Belgium B Simon LinkedSimon BenjaminNo ratings yet

- CheggDocument1 pageCheggabhiNo ratings yet

- Ferren Early Hardcore ListDocument52 pagesFerren Early Hardcore ListdjapulseNo ratings yet

- Noordung, Hermann (Potocnik) - The Problem of Space Travel PDFDocument117 pagesNoordung, Hermann (Potocnik) - The Problem of Space Travel PDFryohky1No ratings yet

- Thaens - NATO Cooperative ESM OperationsDocument11 pagesThaens - NATO Cooperative ESM OperationsMartin Schweighart MoyaNo ratings yet

- Kyusun Choi 2010Document31 pagesKyusun Choi 2010mjrsudhakarNo ratings yet

- Pulse and Pulsefit ManualDocument287 pagesPulse and Pulsefit ManualHRCNo ratings yet

- Security Classification Policy and Procedure: E.O. 12958, As AmendedDocument11 pagesSecurity Classification Policy and Procedure: E.O. 12958, As Amended...tho the name has changed..the pix remains the same.....No ratings yet

- Emf-Cytokine Radiation Sickness ResearchDocument1 pageEmf-Cytokine Radiation Sickness ResearchQuantumGuardianNo ratings yet

- HAARP VLF ResearchDocument43 pagesHAARP VLF ResearchRO-AM-BDNo ratings yet

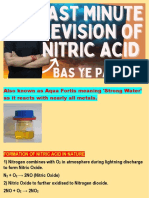

- Nitric Acid Semester 2Document11 pagesNitric Acid Semester 2Aditya M GuptaNo ratings yet

- Strahlenfolter - Electromagnetic Mind Control - Answers-Google-ComDocument3 pagesStrahlenfolter - Electromagnetic Mind Control - Answers-Google-Comstop-organized-crimeNo ratings yet

- Frequency Distribution Problems SolutionsDocument5 pagesFrequency Distribution Problems SolutionsRahul BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Nepal hydropower generator protection relay specificationsDocument5 pagesNepal hydropower generator protection relay specificationsPritam SinghNo ratings yet

- VAV Checkout Sheet 10-22-12Document78 pagesVAV Checkout Sheet 10-22-12archangel571No ratings yet

- Date:-30/12/2019: Feeder - 1 Feeder - 2Document8 pagesDate:-30/12/2019: Feeder - 1 Feeder - 2ddhruvalpNo ratings yet

- 1) - TM 55-1520-210!23!1 Manual de Mantenimiento Bell UH-1HDocument1,187 pages1) - TM 55-1520-210!23!1 Manual de Mantenimiento Bell UH-1HCristian75% (4)

- Forest Theatre Punch List 2014Document10 pagesForest Theatre Punch List 2014L. A. PatersonNo ratings yet

- VRV SCHEDULE TITLEDocument6 pagesVRV SCHEDULE TITLESridhar ReddyNo ratings yet

- StargazerDocument289 pagesStargazerabrabisNo ratings yet

- RandomsDocument2 pagesRandomssborgeltNo ratings yet

- 1801 Aristotles MetaphysicsDocument466 pages1801 Aristotles MetaphysicssborgeltNo ratings yet

- D. H. Lawrence's: Study of Thomas HardyDocument149 pagesD. H. Lawrence's: Study of Thomas HardyAparecida SouzaNo ratings yet

- Human Bond With Crows and RavensDocument7 pagesHuman Bond With Crows and Ravenssborgelt100% (1)

- Mind Controlled Slaves's Articles and BlogsDocument37 pagesMind Controlled Slaves's Articles and Blogssborgelt60% (5)

- Jack Heart - The Blood of Christ - Hemorrhagic Fever, Expendable Humans and Bacteria Gone BeZerk, Paint It BlueDocument44 pagesJack Heart - The Blood of Christ - Hemorrhagic Fever, Expendable Humans and Bacteria Gone BeZerk, Paint It BluesborgeltNo ratings yet

- Crows PDFDocument7 pagesCrows PDFsborgeltNo ratings yet

- Lee Harvey Oswald - Unsung Hero Who Alerted JFK To Assassination Plot' in Chicago - Here Comes The SunDocument17 pagesLee Harvey Oswald - Unsung Hero Who Alerted JFK To Assassination Plot' in Chicago - Here Comes The SunsborgeltNo ratings yet

- Js Bach Complete Edition Liner Notes Sung Texts DownloadDocument272 pagesJs Bach Complete Edition Liner Notes Sung Texts Downloadsborgelt100% (2)

- The Key to Our EnslavementDocument14 pagesThe Key to Our Enslavementsborgelt100% (2)

- Ageism The Silent KillerDocument3 pagesAgeism The Silent Killersborgelt100% (1)

- Flowers of Life Deception PT 2Document15 pagesFlowers of Life Deception PT 2sborgelt100% (4)

- Jack Heart - Alaric Sacks Ohio, Water Wars 2Document12 pagesJack Heart - Alaric Sacks Ohio, Water Wars 2sborgeltNo ratings yet

- Jack Heart - Tiny Monsters, Human Devils & A Poison Park (Water Wars 2Document10 pagesJack Heart - Tiny Monsters, Human Devils & A Poison Park (Water Wars 2sborgeltNo ratings yet

- Jack Heart - Alaric Sacks Ohio, Water Wars 2Document12 pagesJack Heart - Alaric Sacks Ohio, Water Wars 2sborgeltNo ratings yet

- The Rulers of RussiaDocument97 pagesThe Rulers of Russiasquare64100% (1)

- Jack Heart - Return of The Titans - Veterans TodayDocument7 pagesJack Heart - Return of The Titans - Veterans TodaysborgeltNo ratings yet

- A Catechism of The BibleDocument31 pagesA Catechism of The BiblesborgeltNo ratings yet

- Jack Heart - Walk The WalkDocument8 pagesJack Heart - Walk The WalksborgeltNo ratings yet

- The Case For The Latin MassDocument6 pagesThe Case For The Latin MasssborgeltNo ratings yet

- Legal Aspects of Business: Indian Institute of Management, Rohtak Post Graduate ProgrammeDocument5 pagesLegal Aspects of Business: Indian Institute of Management, Rohtak Post Graduate ProgrammeAKANKSHA SINGHNo ratings yet

- Ma Shari - JihadDocument71 pagesMa Shari - JihadNizzatikNo ratings yet

- Laguna Tayabas Bus Co V The Public Service CommissionDocument1 pageLaguna Tayabas Bus Co V The Public Service CommissionAnonymous byhgZINo ratings yet

- Property Ampil Accession Charts C 1 1Document3 pagesProperty Ampil Accession Charts C 1 1ChaNo ratings yet

- Michaels Job ApplicationDocument2 pagesMichaels Job Applicationapi-403740751100% (1)

- Philippine National Bank Wins Appeal Against Uy Teng PiaoDocument2 pagesPhilippine National Bank Wins Appeal Against Uy Teng PiaoAbbyElbambo100% (1)

- Counter ClaimDocument2 pagesCounter ClaimEngelus BeltranNo ratings yet

- Wild Animals - WordsearchDocument2 pagesWild Animals - WordsearchGabriela D AlessioNo ratings yet

- Forensic AnthropologyDocument63 pagesForensic Anthropologyapi-288895705No ratings yet

- ActivityQ2L7,02 Raisin in The SunDocument3 pagesActivityQ2L7,02 Raisin in The SunKazuri RiveraNo ratings yet

- Las Tres C's Del Matrimonio FelizDocument2 pagesLas Tres C's Del Matrimonio FelizRaulNo ratings yet

- Diary of Anne ListerDocument28 pagesDiary of Anne ListerSandra Psi100% (5)

- Pretrial Intervention Program PTIDocument6 pagesPretrial Intervention Program PTIKenneth Vercammen, Esq.100% (1)

- 1920 SlangDocument11 pages1920 Slangapi-249221236No ratings yet

- Antonyms and Synonyms list with Hindi meanings for banking and SSC examsDocument11 pagesAntonyms and Synonyms list with Hindi meanings for banking and SSC examsAbhishek Anand RoyNo ratings yet

- BM Distress OperationDocument1 pageBM Distress OperationJon CornishNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules LRTA Has Standing to Appeal Civil Service RulingDocument18 pagesSupreme Court Rules LRTA Has Standing to Appeal Civil Service RulingKristela AdraincemNo ratings yet

- Apply For Ethiopian Passport Online2Document1 pageApply For Ethiopian Passport Online2yisaccNo ratings yet

- Dube V PSMAS and Another (5 of 2022) (2022) ZWSC 5 (24 January 2022)Document22 pagesDube V PSMAS and Another (5 of 2022) (2022) ZWSC 5 (24 January 2022)toga22No ratings yet

- FIGHT STIGMA WITH FACTSDocument1 pageFIGHT STIGMA WITH FACTSFelicity WaterfieldNo ratings yet

- Dang Vang v. Vang Xiong X. Toyed, 944 F. 2d 476 - Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit 1991Document7 pagesDang Vang v. Vang Xiong X. Toyed, 944 F. 2d 476 - Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit 1991bbcourtNo ratings yet

- Bill of Particulars For Forfeiture of PropertyDocument18 pagesBill of Particulars For Forfeiture of PropertyKrystle HollemanNo ratings yet

- Exploring Smart Sanctions-A Critical Analysis of Zimbabwe Democracy Recovery Act ZDERADocument28 pagesExploring Smart Sanctions-A Critical Analysis of Zimbabwe Democracy Recovery Act ZDERAZimbabwe Delegation100% (1)

- Oct 27 MSHS Chapel Lyrics PPT 20211026Document33 pagesOct 27 MSHS Chapel Lyrics PPT 20211026EstherNo ratings yet

- Private Criminal Complaint v. Eric Calhoun & Alley Kat Bar With Lancaster City Police Response To Scene - September 22, 2007Document6 pagesPrivate Criminal Complaint v. Eric Calhoun & Alley Kat Bar With Lancaster City Police Response To Scene - September 22, 2007Stan J. CaterboneNo ratings yet

- Which Word CANNOT Go in The SpaceDocument2 pagesWhich Word CANNOT Go in The SpaceDuddy EffNo ratings yet

- Ingeborg Simonsson - Legitimacy in EU Cartel Control (Modern Studies in European Law) (2010)Document441 pagesIngeborg Simonsson - Legitimacy in EU Cartel Control (Modern Studies in European Law) (2010)Prafull SaranNo ratings yet

- Arrival in Manila and DapitanDocument3 pagesArrival in Manila and DapitanJessica MalijanNo ratings yet

- Pelaez vs. Auditor GeneralDocument2 pagesPelaez vs. Auditor GeneralPia SarconNo ratings yet

- NTT Application Form (APAC)Document3 pagesNTT Application Form (APAC)RahulNo ratings yet