Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PEOPLE V Maneja

Uploaded by

Charles Roger RayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PEOPLE V Maneja

Uploaded by

Charles Roger RayaCopyright:

Available Formats

PEOPLE v. DIONISIO A.

MANEJA

[ GR No. 47684, Jun 10, 1941 ]

The sole question raised in this appeal is whether the period of prescription for the offense of false

testimony which, in the instant case, is five years (art. 180, No. 4, in relation to art. 90, Revised Penal Code),

should commence from the time the appellee, Dionisio A. Maneja, adduced the supposed false testimony in

criminal case No. 1872 on December 16, 1933, as the lower court held, or, from the time the decision of the

Court of Appeals in the aforesaid basic case became final in December, 1938, as the prosecution contends.

We hold that the theory of the prosecution is the correct one. The period of prescription shall commence to

run from the day on which the crime is discovered by the offended party, the authorities or their agents.

(Art. 91, Revised Penal Code.) With regard to the crime of false testimony, considering that the penalties

provided therefor in article 180 of the Revised Penal Code are, in every case, made to depend upon the

conviction or acquittal of the defendant in the principal case, the act of testifying falsely does not therefore

constitute an actionable offense until the principal case is finally decided. (Cf. U. S. vs. Opinion, 6 Phil., 662,

663; People vs. Marcos et al., G. R. No. 47388, Oct. 22, 1940.) And before an act becomes a punishable

offense, it cannot possibly be discovered as such by the offended party, the authorities or their agents.

If the period of prescription is to be computed from the date the supposed false testimony is given, it would

be impossible to determine the length of such period in any particular case, depending, as it does depend,

on the final outcome of the basic case. For instance, a witness testifies falsely against an accused who is

charged with murder. If the accused is found guilty, the penalty prescribed by law for the perjurer

is reclusion temporal (art. 180, No. 1, Revised Penal Code), in which case the period of prescription is

twenty years (art. 90, idem). On the other hand, if the accused is acquitted, the penalty prescribed for the

perjurer is only arresto mayor (art. 180, No. 4, idem), in which case the period of prescription is only five

years. Upon these hypotheses, if the perjurer is to be prosecuted before final judgment in the basic case, it

would be impossible to determine the period of prescription whether twenty years or five years as either of

these two periods is fixed by law on the basis of conviction or acquittal of the defendant in the main case.

The mere fact that, in the present case, the penalty for the offense of false testimony is the same, whether

the defendant in criminal case No. 1872 were convicted or acquitted, is of no moment, it being a matter of

pure co-incidence. The four cases enumerated in article 180. of the Revised Penal Code and the instant case

falls on one of them uniformly presuppose a final judgment of conviction or acquittal in the basic case as a

prerequisite to the action ability of the crime of false testimony.

Order of dismissal is reversed, and let the case be remanded to the court of origin for further proceedings,

without costs.

FACTS: Dionisio Maneja was charged of false testimony. He did such act on 1933. The case he testifed to

became final in 1938. Maneja contends that his offense has prescribed.

ISSUE: Whether the crime has prescribed.

RULING: The SC ruled that the period of prescription shall start from the day the crime was discovered by

the offended party, the authorities or their agents. With false testimony, it is not an actionable offense until

the case is decided. For one to be judged of falsely testifying there should a decision on the case he testified

to. In short, there is no prescription present yet. The SC reversed the dismissal and remanded it to the court

of origin.

You might also like

- People v. de JesusDocument3 pagesPeople v. de JesusSnep MediaNo ratings yet

- People v. Lagarto, 196 SCRA 611 (1991) DigestDocument2 pagesPeople v. Lagarto, 196 SCRA 611 (1991) DigestChristian SicatNo ratings yet

- Philippines Supreme Court upholds death penalty for robbery accompliceDocument4 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court upholds death penalty for robbery accompliceLu CasNo ratings yet

- People Vs de Guzman GR No 77368Document1 pagePeople Vs de Guzman GR No 77368Norway AlaroNo ratings yet

- People V. Ortega G.R. No. 116736, July 24, 1997 Panganiban, J. Thesis StatementDocument3 pagesPeople V. Ortega G.R. No. 116736, July 24, 1997 Panganiban, J. Thesis StatementHaengwoonNo ratings yet

- Murder Conviction Upheld for Double Killing in Camarines SurDocument335 pagesMurder Conviction Upheld for Double Killing in Camarines SurMarkNo ratings yet

- 40 - Us. V. Apostol, 14 Phil 92 (1909)Document2 pages40 - Us. V. Apostol, 14 Phil 92 (1909)Digesting FactsNo ratings yet

- People v. OanisDocument4 pagesPeople v. Oanisdaryll generynNo ratings yet

- People v Tangan Homicide CaseDocument4 pagesPeople v Tangan Homicide CaseIna VillaricaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 218209 - Lechoncito, Trexia Mae DDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 218209 - Lechoncito, Trexia Mae DTrexiaLechoncitoNo ratings yet

- 11 US Vs Maralit (January 25 1971)Document1 page11 US Vs Maralit (January 25 1971)EuniceNo ratings yet

- People - v. - Elias Rodriguez PDFDocument4 pagesPeople - v. - Elias Rodriguez PDFJoy NavalesNo ratings yet

- People v de Guzman Case - Marriage Extinguishes Criminal Liability for RapeDocument2 pagesPeople v de Guzman Case - Marriage Extinguishes Criminal Liability for RapeChristian Kenneth TapiaNo ratings yet

- 95 RCBC Vs CADocument1 page95 RCBC Vs CAangelo doceoNo ratings yet

- People Vs CastromeroDocument12 pagesPeople Vs CastromerotheresagriggsNo ratings yet

- Aggravating DigestDocument2 pagesAggravating DigestLorelei B RecuencoNo ratings yet

- CRIM1 Padilla v. DizonDocument7 pagesCRIM1 Padilla v. DizonChedeng KumaNo ratings yet

- People v. Mabug-At 51 PHIL 967Document5 pagesPeople v. Mabug-At 51 PHIL 967Anonymous0% (1)

- 61 Phil 703, PP Vs LamahangDocument3 pages61 Phil 703, PP Vs LamahanggcantiverosNo ratings yet

- GUTIERREZ HERMANOS V OrenseDocument3 pagesGUTIERREZ HERMANOS V OrensedelayinggratificationNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 166401 (October 30, 2006) Tinga, J.: People vs. BonDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 166401 (October 30, 2006) Tinga, J.: People vs. BonbrendamanganaanNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction Cases (Digest)Document7 pagesStatutory Construction Cases (Digest)andrea ibanezNo ratings yet

- Criminal LawDocument21 pagesCriminal LawDee WhyNo ratings yet

- JUAN PONCE ENRILE vs. HON. OMAR U. AMIN, GR 93335Document4 pagesJUAN PONCE ENRILE vs. HON. OMAR U. AMIN, GR 93335Recalle Icel0% (1)

- Case Digest of People Vs Abilong 82 Phil 174Document1 pageCase Digest of People Vs Abilong 82 Phil 174Lord Jester AguirreNo ratings yet

- In Re Habeas Corpus of Pete Lagran Case DigestDocument1 pageIn Re Habeas Corpus of Pete Lagran Case DigestJerric CristobalNo ratings yet

- 60 People v. Formigones LeeDocument1 page60 People v. Formigones LeeGTNo ratings yet

- People vs Rodriguez illegal possession firearm absorbed rebellionDocument1 pagePeople vs Rodriguez illegal possession firearm absorbed rebellionDigesting FactsNo ratings yet

- SC rules testimony must be material to caseDocument11 pagesSC rules testimony must be material to casesamdelacruz1030No ratings yet

- 100 People v. Capalac, 1117 SCRA 874Document2 pages100 People v. Capalac, 1117 SCRA 874Princess MarieNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Affirms Death Penalty for Prison MurderDocument4 pagesSupreme Court Affirms Death Penalty for Prison MurderFidelis Victorino QuinagoranNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz vs. People GR 189405 November 19, 2014 Case DigestDocument3 pagesDela Cruz vs. People GR 189405 November 19, 2014 Case Digestbeingme2No ratings yet

- US v. Bumanglang, 14 Phil 644 (1909)Document10 pagesUS v. Bumanglang, 14 Phil 644 (1909)Glenn caraigNo ratings yet

- Espiritu v. CA and Masauding G.R. No. 115640, March 15, 1995Document1 pageEspiritu v. CA and Masauding G.R. No. 115640, March 15, 1995Shari Realce AndeNo ratings yet

- People Vs Pedro PagalDocument1 pagePeople Vs Pedro PagalEloisa TalosigNo ratings yet

- People Vs CampuhanDocument2 pagesPeople Vs CampuhanFrancis Coronel Jr.No ratings yet

- Conspiracy and Proposal To Commit A FelonyDocument2 pagesConspiracy and Proposal To Commit A FelonysjbloraNo ratings yet

- People V AlfecheDocument4 pagesPeople V Alfechemark kenneth cataquizNo ratings yet

- People Versus CrimDocument5 pagesPeople Versus Crimphoebelaz100% (1)

- 69 People V LucasDocument2 pages69 People V LucasAmberChanNo ratings yet

- Flavio K - Macasaet & Associates, Inc. vs. Com. On Audit 173 SCRA 352, May 12, 1989Document6 pagesFlavio K - Macasaet & Associates, Inc. vs. Com. On Audit 173 SCRA 352, May 12, 1989MarkNo ratings yet

- Crim - People V OyanibDocument11 pagesCrim - People V OyanibKenny HotingoyNo ratings yet

- Colinares Vs PeopleDocument2 pagesColinares Vs PeopleMacNo ratings yet

- Tanega v. MasakayanDocument1 pageTanega v. MasakayanEthan KurbyNo ratings yet

- 8 - Garces v. PeopleDocument2 pages8 - Garces v. PeopleAnonymous uMI5BmNo ratings yet

- Del Castillo Vs Judge TorrecampoDocument2 pagesDel Castillo Vs Judge TorrecampoGerald Hernandez100% (2)

- Court Cannot Fix Period Where Contract Establishes Reasonable TimeDocument2 pagesCourt Cannot Fix Period Where Contract Establishes Reasonable TimeJcNo ratings yet

- People vs. Credo GR No 197369 July 13, 2013 FactsDocument2 pagesPeople vs. Credo GR No 197369 July 13, 2013 FactsJet OrtizNo ratings yet

- People Vs BalotolDocument2 pagesPeople Vs Balotolmorriss hadsamNo ratings yet

- University of The Philippines College of Law: RelevantDocument3 pagesUniversity of The Philippines College of Law: RelevantSophiaFrancescaEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Cheng Vs Sy 592 Scra 155Document10 pagesCheng Vs Sy 592 Scra 155Yram DulayNo ratings yet

- Joaquin Vs Navarro, 93 Phil 257 (1953)Document8 pagesJoaquin Vs Navarro, 93 Phil 257 (1953)akosiJRNo ratings yet

- 27 Mondragon Vs People (Long Digest)Document2 pages27 Mondragon Vs People (Long Digest)Carie LawyerrNo ratings yet

- Agapay V PalangDocument2 pagesAgapay V PalangLaurence Brian HagutinNo ratings yet

- Crim 2 Part 7Document43 pagesCrim 2 Part 7mccm92No ratings yet

- United States Vs Dela Cruz DigestDocument1 pageUnited States Vs Dela Cruz Digestavocado booksNo ratings yet

- 86 People V Ricohermoso 56 Scra 431Document5 pages86 People V Ricohermoso 56 Scra 431fjl300No ratings yet

- PEOPLE VS COMADRE ON USE OF EXPLOSIVESDocument1 pagePEOPLE VS COMADRE ON USE OF EXPLOSIVESsashinaNo ratings yet

- People Vs MarasiganDocument4 pagesPeople Vs Marasigancrisey1No ratings yet

- People VS ManejaDocument2 pagesPeople VS ManejaMa Donna Thea BanjaoNo ratings yet

- Philippine Legal Doctrines 05Document1 pagePhilippine Legal Doctrines 05Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Legal Doctrines 03Document1 pagePhilippine Legal Doctrines 03Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Legal Doctrines 02Document1 pagePhilippine Legal Doctrines 02Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- Attorney fees dispute resolved without further paymentDocument1 pageAttorney fees dispute resolved without further paymentCharles Roger Raya100% (1)

- Atty Santiago Suspended for Invalid Separation ContractDocument2 pagesAtty Santiago Suspended for Invalid Separation ContractKing BadongNo ratings yet

- Philippine Legal Doctrines 01Document1 pagePhilippine Legal Doctrines 01Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- MAURICIO SAYSON Versus THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS, DELIA SAYSONDocument1 pageMAURICIO SAYSON Versus THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS, DELIA SAYSONCharles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- LUCAS G. ADAMSON Versus COURT OF APPEALS and LIWAYWAY VINZONS-CHATO, in Her Capacity As Commissioner of The Bureau of Internal RevenueDocument1 pageLUCAS G. ADAMSON Versus COURT OF APPEALS and LIWAYWAY VINZONS-CHATO, in Her Capacity As Commissioner of The Bureau of Internal RevenueCharles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE Versus PASCOR REALTY AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, ROGELIO A. DIO and VIRGINIA S. DIODocument1 pageCOMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE Versus PASCOR REALTY AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, ROGELIO A. DIO and VIRGINIA S. DIOCharles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Versus THE COURT OF APPEALS, and NIELSON & COMPANY, INC.Document1 pageREPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Versus THE COURT OF APPEALS, and NIELSON & COMPANY, INC.Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, Petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, ATLAS CONSOLIDATED MINING AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION and COURT OF TAX APPEALS, Respondents.Document1 pageCOMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, Petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, ATLAS CONSOLIDATED MINING AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION and COURT OF TAX APPEALS, Respondents.Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- Castaneda vs. Ago, G.R. No. L-28546, July 30, 1975..Document1 pageCastaneda vs. Ago, G.R. No. L-28546, July 30, 1975..Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of The Charges of Plagiarism, Etc., Against Associate Justice Mariano C. Del CastilloDocument2 pagesIn The Matter of The Charges of Plagiarism, Etc., Against Associate Justice Mariano C. Del CastilloCharles Roger Raya100% (1)

- Lao Vs MedelDocument1 pageLao Vs MedelNicole Marie Abella Cortes0% (1)

- Chua VDocument2 pagesChua VAnthony AraulloNo ratings yet

- CASIANO U. LAPUT, Petitioner, vs. ATTY. FRANCISCO E.F. REMOTIGUE and ATTY. FORTUNATO P. PATALINGHUG, Respondents.Document1 pageCASIANO U. LAPUT, Petitioner, vs. ATTY. FRANCISCO E.F. REMOTIGUE and ATTY. FORTUNATO P. PATALINGHUG, Respondents.Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- Santayana vs. Alampay, A.C. No. 5878, March 21, 2005Document2 pagesSantayana vs. Alampay, A.C. No. 5878, March 21, 2005Charles Roger Raya50% (2)

- WILSON PO CHAM, Complainant, vs. ATTY. EDILBERTO D. PIZARRO, Respondent.Document2 pagesWILSON PO CHAM, Complainant, vs. ATTY. EDILBERTO D. PIZARRO, Respondent.Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court rules against libel case between opposing counselsDocument1 pageSupreme Court rules against libel case between opposing counselsCharles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- In Re Vailoces, A.M. No. 439, September 30, 1982Document1 pageIn Re Vailoces, A.M. No. 439, September 30, 1982Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- Lao Vs MedelDocument1 pageLao Vs MedelNicole Marie Abella Cortes0% (1)

- FELICIDAD L. ORONCE and ROSITA L. FLAMINIANO, Petitioners, vs. CA AND GONZALESDocument1 pageFELICIDAD L. ORONCE and ROSITA L. FLAMINIANO, Petitioners, vs. CA AND GONZALESCharles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- WILSON PO CHAM, Complainant, vs. ATTY. EDILBERTO D. PIZARRO, Respondent.Document2 pagesWILSON PO CHAM, Complainant, vs. ATTY. EDILBERTO D. PIZARRO, Respondent.Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- ANA MARIE CAMBALIZA, Complainant, vs. ATTY. ANA LUZ B. CRISTAL-TENORIO, Respondent.Document1 pageANA MARIE CAMBALIZA, Complainant, vs. ATTY. ANA LUZ B. CRISTAL-TENORIO, Respondent.Charles Roger Raya100% (2)

- SURIGAO MINERAL RESERVATION BOARD, ET AL., Petitioners, vs. HON. GAUDENCIO CLORIBEL ETC., ET AL., RespondentsDocument2 pagesSURIGAO MINERAL RESERVATION BOARD, ET AL., Petitioners, vs. HON. GAUDENCIO CLORIBEL ETC., ET AL., RespondentsCharles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- PHILAM ASSET MANAGEMENT, INC. v. COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUEDocument1 pagePHILAM ASSET MANAGEMENT, INC. v. COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUECharles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- RHEEM OF THE PHILIPPINES, INC., ET AL., Petitioners, vs. ZOILO R. FERRER, ET AL., Respondents.Document1 pageRHEEM OF THE PHILIPPINES, INC., ET AL., Petitioners, vs. ZOILO R. FERRER, ET AL., Respondents.Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- ISIDRO SANTOS vs. LEANDRA MANARANG, AdministratrixDocument2 pagesISIDRO SANTOS vs. LEANDRA MANARANG, AdministratrixCharles Roger Raya0% (1)

- SITHE PHILIPPINES HOLDINGS, INC. v. COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUEDocument1 pageSITHE PHILIPPINES HOLDINGS, INC. v. COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUECharles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- ELENA MORENTE, Petitioners - Versus - GUMERSINDO DE LA SANTA, Respondent.Document1 pageELENA MORENTE, Petitioners - Versus - GUMERSINDO DE LA SANTA, Respondent.Charles Roger RayaNo ratings yet

- Cybersecurity 2022: Defending Against Evolving ThreatsDocument50 pagesCybersecurity 2022: Defending Against Evolving ThreatsMacloutNo ratings yet

- Lakeside Park Subdivision San Pablo City LagunaDocument2 pagesLakeside Park Subdivision San Pablo City LagunaRose VecinalNo ratings yet

- Batas MilitarDocument2 pagesBatas MilitariamleleiNo ratings yet

- Capstone Project / Research: Learning Activity Sheet 3Document8 pagesCapstone Project / Research: Learning Activity Sheet 3maricel magnoNo ratings yet

- Danger Signs: Pedestrians & MotoristsDocument1 pageDanger Signs: Pedestrians & MotoristsHonolulu Star-AdvertiserNo ratings yet

- TEST YOURSELF - 12/05/2021: Unique Cycling Tour To Discover Simple Life in HueDocument2 pagesTEST YOURSELF - 12/05/2021: Unique Cycling Tour To Discover Simple Life in Huephương anh phạmNo ratings yet

- How To Start A 508 (C) (1) (A) ChurchDocument4 pagesHow To Start A 508 (C) (1) (A) ChurchPhoebe Freeman78% (18)

- Personal Reflection v1Document4 pagesPersonal Reflection v1api-475669793No ratings yet

- Philippines executive departments guideDocument2 pagesPhilippines executive departments guideDiazmean Gonzales SoteloNo ratings yet

- Student Upload Sample 1yDocument65 pagesStudent Upload Sample 1yRushabh PatelNo ratings yet

- Activities For Auditors During Vessel Visit For AuditsDocument1 pageActivities For Auditors During Vessel Visit For Auditssandeepkumar2311No ratings yet

- O.M. - Service Process Selection and DesignDocument22 pagesO.M. - Service Process Selection and DesignROHAN CHOPDE100% (4)

- Popular Culture:: Definitions, Contexts, and TheoriesDocument27 pagesPopular Culture:: Definitions, Contexts, and TheoriesAcib Ritc50% (2)

- 1.1 The Important of Technology in Everyday LifeDocument15 pages1.1 The Important of Technology in Everyday Lifeaduka_wiranaNo ratings yet

- Group 3 - PROCTOR AND GAMBLE ORGANIZATION 2005Document19 pagesGroup 3 - PROCTOR AND GAMBLE ORGANIZATION 2005RehanshuVij100% (2)

- MGMT623 Quiz No2Document4 pagesMGMT623 Quiz No2luke castorNo ratings yet

- SWIFT Customer Security Controls Framework: Secure Access &Document8 pagesSWIFT Customer Security Controls Framework: Secure Access &Ruslan SoloviovNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance and National Culture: A Multi-Country StudyDocument16 pagesCorporate Governance and National Culture: A Multi-Country StudyMunib HussainNo ratings yet

- Leave Form Rev.1Document32 pagesLeave Form Rev.1lyn dela cruzNo ratings yet

- Powder Nickel BUSINESS PLAN (Summary) Presentation - Indonesia PDFDocument93 pagesPowder Nickel BUSINESS PLAN (Summary) Presentation - Indonesia PDFDark CygnusNo ratings yet

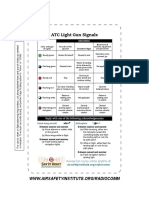

- At C Light Gun SignalsDocument1 pageAt C Light Gun SignalsJorge CastroNo ratings yet

- Holistic E-Learning in Nigerian Higher Education InstitutionsDocument7 pagesHolistic E-Learning in Nigerian Higher Education InstitutionsJournal of ComputingNo ratings yet

- MARKETING MANAGEMENT CHAPTERDocument31 pagesMARKETING MANAGEMENT CHAPTERammuajayNo ratings yet

- ETECH COT 2ND SEM-Online NettiqueteDocument1 pageETECH COT 2ND SEM-Online NettiqueteAbraham BojosNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Lesson 2Document4 pagesUnit 2 Lesson 2api-240273723No ratings yet

- Module 7 Material Self and Spiritual SelfDocument28 pagesModule 7 Material Self and Spiritual Selfxela100% (3)

- Surveying With Construction Applications 8th Edition Kavanagh Solutions ManualDocument7 pagesSurveying With Construction Applications 8th Edition Kavanagh Solutions ManuallujydNo ratings yet

- De - Continuous Assessment Card - FormatDocument9 pagesDe - Continuous Assessment Card - FormatMansi Trivedi0% (1)

- Software Requirement Specification: 3.1.1 PurposeDocument4 pagesSoftware Requirement Specification: 3.1.1 Purposevishalmate10No ratings yet

- Question Bank Bachelor of Computer Application (BCA-11) BCA Fifth Semester BCA-18 E-Commerce Section-A (Long Answer Type Questions)Document4 pagesQuestion Bank Bachelor of Computer Application (BCA-11) BCA Fifth Semester BCA-18 E-Commerce Section-A (Long Answer Type Questions)priyankaNo ratings yet