Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Neurology in Practice: The Bare Essentials of Uro-Neurology

Uploaded by

LearnedWritingOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Neurology in Practice: The Bare Essentials of Uro-Neurology

Uploaded by

LearnedWritingCopyright:

Available Formats

Neurology in Practice

THE BARE ESSENTIALS

Uro-Neurology

Jalesh N Panicker,1 Clare J Fowler2

1

Locum Consultant Neurologist Neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction—the external and internal urethral sphincters,

in Uro-Neurology, Department so-called neurogenic bladder—can result from along with parasympathetic mediated detru-

of Uro-Neurology, The National many neurological conditions. The importance sor contraction.

Hospital for Neurology and

Neurosurgery, UCL Institute of of this problem to patient health and quality of ▶ Intact neural pathways between the bladder

Neurology, London, UK life is now better recognised, particularly as these and the pontine micturition centre are essen-

2

Professor of Uro-Neurology, days many of the symptoms can be treated.

Department of Uro-Neurology,

tial for the coordinated activity between the

The National Hospital for detrusor and urethral sphincters.

Neurology and Neurosurgery, ▶ The prefrontal cortex is responsible for com-

UCL Institute of Neurology, THE LOWER URINARY TRACT AND ITS

plex cognitive and socially appropriate behav-

London, UK NEUROLOGICAL CONTROL

iours, including voiding.

Optimal patient management requires an under-

Correspondence to standing of the physiology of the lower urinary

Dr J N Panicker, Department

of Uro-Neurology, The National tract, and its derangement in neurological dis- NEUROGENIC BLADDER DYSFUNCTION

Hospital for Neurology and ease. The lower urinary tract consists of the blad- Storage phase dysfunction most commonly

Neurosurgery, UCL Institute der and urethra and has just two roles: storage of results from lesions of the spinal or suprapontine

of Neurology, London WC1N urine and voiding at appropriate times. To regu-

3BG, UK; pathways controlling micturition. This results in

j.panicker@ion.ucl.ac.uk late this, a complex neural control system acts involuntary spontaneous or induced contractions

like a switching circuit to maintain a reciprocal of the detrusor muscle (detrusor overactivity)

relationship between the reservoir (storage) func- which can be identified during the fi lling phase in

tion of the bladder and the continence (voiding) urodynamic studies (figure 2).

function of the urethra (figure 1). The pontine Voiding phase dysfunction usually results from

micturition centre is responsible for switching lesions of the spinal or infrasacral pathways.

between the ‘storage’ phase and ‘voiding’ phase. In myelopathy, this is due to simultaneous con-

It in turn receives input from other centres, par- traction of the external urethral sphincter and

ticularly the periaqueductal grey of the midbrain, detrusor muscle—detrusor–sphincter dyssyner-

hypothalamus and cortical areas such as the pre- gia—which can result in both incomplete bladder

frontal cortex. emptying and abnormally high pressures in the

bladder. Impaired detrusor contractions due to

Storage phase reduced parasympathetic drive from the descend-

▶ In health, the bladder is in the storage phase for ing bulbospinal pathways may also contribute to

99.8% of the time, achieved by inhibition of incomplete bladder emptying. In lesions affect-

parasympathetic activity and so relaxation of ing the infrasacral pathway, such as of the cauda

the detrusor muscle of the bladder wall. This equina (or occasionally a peripheral neuropathy),

results in ‘bladder compliance’ so that intra- voiding dysfunction results from poorly sustained

vesical pressure remains below 10 cm H 2O. detrusor contractions and possibly non-relaxing

sphincters.

▶ Simultaneously, sympathetic and pudendal

nerve mediated tonic contraction of the ure-

thral sphincters ensures continence. COMPLICATIONS ARISING FROM THE

▶ Functional imaging suggests that the pon- NEUROGENIC BLADDER

tine micturition centre is tonically inhib- ▶ Detrusor overactivity and reduced bladder

ited during bladder filling by signals arising wall compliance result in raised intravesical

from the periaqueductal grey. Other areas pressure which can in turn lead to structural

that show ‘activation’ during bladder fill- changes in the bladder wall such as trabecula-

ing include the anterior cingulate gyrus and tions and diverticuli.

right insula. ▶ The upper urinary tract (kidney and ureter)

can also show changes such as vesicoureteric

Voiding phase reflux and hydronephrosis, predisposing to

▶ When it is consciously deemed appropriate renal impairment and even end stage renal

to void, the periaqueductal grey no longer disease.

exerts tonic inhibition on the pontine mic- ▶ For reasons that are unclear, upper urinary

turition centre. This results in relaxation tract damage and renal failure are surprisingly

of the pelvic floor muscles as well as the unusual in multiple sclerosis (MS).

178 2010;10:178–185. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.213892

Neurology in Practice

Figure 1 Innervation of the lower urinary tract. (A) Sympathetic fibres (blue) originate in the T11–L2 segments of the spinal cord and run through

the inferior mesenteric ganglia (inferior mesenteric plexus, IMP) and the hypogastric nerve (HGN) or through the paravertebral chain to join the pelvic

nerves at the base of the bladder and the urethra. Parasympathetic preganglionic fibres (green) arise from the S2–S4 spinal segments and travel in

sacral roots and pelvic nerves (PEL) to ganglia in the pelvic plexus (PP) and in the bladder wall; this is where the postganglionic nerves that supply

parasympathetic innervation to the bladder arise. Somatic motor nerves (yellow) that supply the striated muscles of the external urethral sphincter

arise from S2–S4 motor neurons and pass through the pudendal nerves. L1, first lumbar root; S1, first sacral root; SHP, superior hypogastric plexus; SN,

sciatic nerve; T9, ninth thoracic root. (B) Efferent pathways and neurotransmitter mechanisms that regulate the lower urinary tract. Parasympathetic

postganglionic axons in the pelvic nerve release acetylcholine (ACh) which produces bladder contraction by stimulating M3 muscarinic receptors in the

bladder wall smooth muscle. Sympathetic postganglionic neurons release noradrenaline (NA) which activates β3 adrenergic receptors to relax bladder

wall smooth muscle and activate α1 adrenergic receptors to contract urethral smooth muscle. Somatic axons in the pudendal nerve also release ACh

which produces contraction of the external sphincter striated muscle by activating nicotinic cholinergic receptors. Reproduced with permission from

Fowler et al (Nat Rev Neurosci 2008;9:453–66).

▶ On the other hand, patients with spinal cord ▶ Patients with storage dysfunction complain of

injury are prone to upper tract damage and frequency of micturition, nocturia, urgency

renal disease, and have five times the age stan- and urgency incontinence.

dardised risk for renal failure compared with ▶ Patients with voiding dysfunction complain

the general adult population. of hesitancy, straining for micturition, slow

▶ Similarly, the risk is higher in adults with spina and interrupted stream or may be in urinary

bifida, who have an eight times risk for devel- retention. Unfortunately, the history of void-

oping renal failure, and this may be a leading ing function is often unreliable as more than

cause of death. 50% of patients may be unaware of incomplete

▶ Risk of renal failure is highest in patients who bladder emptying. The history should there-

have raised intravesical pressure due to detru- fore be supplemented by a bladder scans (see

sor overactivity, low bladder compliance and a below).

competent bladder neck. ▶ The bladder diary records the time and vol-

▶ Patients are prone to various genitourinary ume of each voiding, urinary output and epi-

tract infections such as cystitis, pyelonephri- sodes of incontinence and urgency, and is an

tis and epididymo-orchitis and also to bladder extension of the history (figure 3).

stones.

Screening for urinary tract infections

Combined rapid tests of urine, using reagent strips

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION for urinalysis (‘dipstick’ test), is advisable for

History patients presenting with new bladder symptoms

As ever, history taking is the cornerstone of evalu- or at follow-up if there are unexplained changes in

ation and should assess both the storage and void- bladder symptoms. The negative predictive value

ing phases of micturition. for excluding urinary tract infection is 98% but

2010;10:178–185. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.213892 179

Neurology in Practice

Figure 2 Filling cystometry demonstrating detrusor overactivity. Red trace (Pabd), intra-abdominal pressure recorded by the rectal catheter; dark

blue trace (Pves), intravesical pressure recorded by the bladder catheter; pink trace (Pdet), subtracted detrusor pressure (Pves−Pabd). Green traces

represent volume infused during the test (Vinf) and volume voided (Vura) while the orange trace represents urinary flow (Qura). Black arrows indicate

detrusor overactivity and black arrowhead indicates incontinence.

Figure 3 Bladder diary

over 24 h demonstrating

daytime and night-time

frequency, low volume

voids and incontinence,

in a patient with detrusor

overactivity.

the positive predictive value for confi rming infec- Urodynamics

tion is only 50%. Urodynamic tests assess detrusor and bladder

outlet function.

▶ Uroflowmetry is a non-invasive assessment of

Measurement of postvoid residual urine

Because the extent of incomplete bladder empty- voiding (figure 4).

ing cannot be predicted from the history or clini- ▶ Filling cystometry and pressure–flow studies

cal examination, it is often important to estimate are more invasive tests that measure pressure–

postvoid residual urine by ultrasonography, most volume relationships during bladder fi lling

commonly using a portable bladder scanner, or by and voiding (figure 2).

‘in–out’ catheterisation. ▶ Urodynamic evaluation also helps to identify

Ultrasonography is helpful to exclude compli- concomitant local disorders that may contribute

cations such as bladder stones and should be per- to lower urinary tract dysfunction such as bladder

formed periodically to assess the integrity of the outlet obstruction due to prostate enlargement

upper urinary tract in patients known to be at in men and stress incontinence in women, and

risk of damage. their relative contribution to bladder symptoms.

180 2010;10:178–185. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.213892

Neurology in Practice

▶ Videourodynamics uses fluoroscopic x-ray dysfunction and increasing cognitive impairment

monitoring during urodynamics and allows tend to be related.

demonstration of vesicoureteral reflux and any

structural abnormalities of the bladder and ▶ Patients may have detrusor overactivity as a

bladder neck. result of the underlying neurodegenerative

changes affecting the suprapontine centres

responsible for bladder control

The need for a complete urodynamic study in

▶ Cognitive and behavioural problems, urologi-

every patient with neurogenic bladder symptoms

cal/urogynaecological causes, immobility and

is the subject of debate. Patients with spinal cord

cholinesterase inhibitors may contribute to

injury, spina bifida and possibly advanced MS

incontinence

should undergo urodynamic studies because of

▶ On the other hand, incontinence, urinary tract

their higher risk of upper tract involvement and

infections and several of the antimuscarinic

renal impairment, although ultrasound of the

medications used for treating detrusor overac-

upper tract is a less invasive method for monitor-

tivity may worsen cognitive and behavioural

ing structural changes. In early MS, urodynamics

problems.

should be carried out only in those whose urinary

symptoms are refractory to conservative treat-

ment or who are bothered by their symptoms and Stroke

wish to undergo further interventions. More than 50% of stroke patients have urinary

The pattern of bladder symptoms, and results incontinence during the acute phase. Risk factors

of these various tests, depend on the level of the for incontinence include lesion size, concomi-

neurological lesion (table 1). tant illnesses such as diabetes and increasing

age. Lesions in the anteromedial frontal lobe and

putamen are more commonly associated with

CAUSES OF NEUROGENIC LOWER URINARY incontinence. The burden of white matter hyper-

TRACT DYSFUNCTION intensities causing leukoariaosis is as powerful a

Dementia risk factor for urinary incontinence as damage in

Incontinence is often a prominent symptom and specific regions. Incontinence is independently

it tends to occur early in normal pressure hydro- associated with the severity of neurological dis-

cephalus, dementia with Lewy bodies, vascu- ability and institutionalisation.

lar dementia and frontotemporal dementia but

later on in the course of Alzheimer’s disease

Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy

and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Bladder

The severity of lower urinary tract dysfunction

in Parkinson’s disease is correlated with the stage

of the disease, suggesting a relationship between

dopamine loss and bladder dysfunction. Urgency

and frequency are the commonest symptoms,

resulting from detrusor overactivity.

Bladder symptoms in multiple system atrophy

often precede other clinical manifestations; in

the early stages, incontinence usually arises from

detrusor overactivity but incomplete bladder emp-

tying and urinary retention become the predomi-

nant problems as the disease progresses. An open

bladder neck on videourodynamics is often seen

in men with multiple system atrophy.

MS and other demyelinating disorders

Problems with micturition are very common in

MS, generally correlating with the severity of the

Figure 4 Uroflowmetry, a non-invasive test for voiding functions, demonstrating urinary

disease and lower limb pyramidal dysfunction.

flow with a normal bell shaped curve and a maximum flow rate of 21 ml/s.

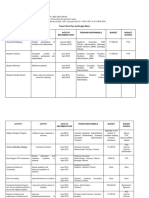

Table 1 Diagnostic evaluation of neurogenic bladder dysfunction

Suprapontine lesion (eg, stroke, Infrapontine suprasacral lesion Infrasacral lesion (eg, conus

Parkinson’s disease) (eg, myelopathy) medullaris, cauda equina)

Symptoms: Urgency, frequency, urgency Urgency, frequency, urgency incontinence, hesitancy, Hesitancy, retention

History and bladder diary incontinence retention

Bladder scan: No postvoid residual urine ±Raised postvoid residual urine Postvoid residual urine >100 ml

Postvoid residual urine

Uroflowmetry Normal flow Interrupted flow Poor/absent flow

Urodynamics Detrusor overactivity Detrusor overactivity,detrusor–sphincter Detrusor underactivity, sphincter

dyssynergia insufficiency

2010;10:178–185. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.213892 181

Neurology in Practice

Most commonly, patients report storage symp-

toms such as urgency and frequency. Voiding Box 1 Non-urological causes for urinary

symptoms depend on the degree of spinal cord retention

involvement. Bladder dysfunction is also common

in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and may

persist after the other neurological impairments Neurological causes

▶ Detrusor external sphincter dyssynergia

have resolved.

(eg, due to myelopathy)

▶ Detrusor underactivity: loss of voluntary

Spinal cord injury voiding (lesion of conus medullaris or

Patients may initially be in retention during the spinal roots), multiple system atrophy, pure

acute stage of spinal shock but they then develop autonomic failure, radical pelvic surgery

the typical pattern of detrusor–sphincter dyssyn- ▶ Meningitis retention syndrome

ergia and detrusor overactivity as spinal reflexes Non-neurological causes

return. ▶ Primary disorder of urethral sphincter

relaxation (Fowler’s syndrome)

▶ Dysfunctional voiding (behavioural)

Spina bifida

▶ Medications: anticholinergics, opiates

More than 90% of children with spina bifida

▶ Primary detrusor muscle failure

have bladder dysfunction, through deficits in

the somatic as well as the autonomic innerva-

tion of the bladder. Symptoms generally start in

infancy or childhood but occasionally in adult-

hood. Urodynamic studies demonstrate a vari- Box 2 Fowler’s syndrome (primary disorder

ety of fi ndings: detrusor overactivity, detrusor of urethral sphincter relaxation)

underactivity or low bladder compliance with

ineffective contractions. The bladder outlet

may show detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia or it

Clinical features

▶ Young women, aged 15–30 years

may be incompetent with a static or fi xed distal

▶ Chronic urinary retention, no urge, bladder

sphincter. Young patients with normal bladder

function can develop lower urinary tract dys-

volume >1000 ml

▶ No evidence of urological or neurological

function later on in life as a result of spinal cord

tethering and bladder symptoms should be reg-

disease

▶ Straining does not improve bladder emptying

ularly reviewed.

▶ Pain with clean intermittent self-catheterisation,

particularly when removing catheter

Cauda equina syndrome ▶ Many have polycystic ovaries and are hirsute,

Lower motor neuron disturbance affecting the obese with acne, have menstrual irregularities

sacral nerve roots can result in voiding dysfunc- and infertility

tion and chronic urinary retention due to reduced ▶ Several patients are taking opiates, most

or absent detrusor contractions. Patients may often for back pain, musculoskeletal pain or

notice reduced sensation of bladder fi lling, inabil- endometriosis, which may cause persistence

ity to initiate micturition voluntarily and eventu- of retention and worsening bladder emptying

ally bladder distension to the point of overflow Investigations

incontinence. However, some patients may occa- ▶ Raised maximum urethral pressure

sionally have detrusor overactivity. ▶ Increased urethral sphincter volume on

ultrasound

▶ Concentric needle EMG of the urethral sphincter

URINARY RETENTION

demonstrating characteristic findings of

Iatrogenic causes from medications are often

complex repetitive discharges and decelerating

missed—opiates, medications with anticholin-

bursts

ergic properties (eg, antipsychotic drugs, antide-

Treatment

pressants and anticholinergic respiratory agents),

▶ The only effective treatment to restore voiding

α-adrenoceptor agonists, benzodiazepines,

is sacral neuromodulation

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cal-

cium channel antagonists may all cause urinary

retention. MANAGEMENT

Neurologists are sometimes referred patients The goals are to achieve continence, improve

in urinary retention after a urological evaluation quality of life, prevent urinary tract infections

has excluded a ‘structural’ lesion obstructing the and preserve upper urinary tract function.

lower urinary tract. Once history, examination

and relevant investigations such as spinal MRI,

clinical neurophysiology and perhaps lumbar Voiding dysfunction

puncture have excluded a neurological cause, var- Before starting treatment, the postvoid residual

ious functional disorders need to be considered volume should be measured; in patients with

(box 1 and 2). impaired voiding, more than 100 ml is likely to

182 2010;10:178–185. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.213892

Neurology in Practice

contribute to bladder dysfunction. A single mea- ▶ Caffeine reduction may reduce urgency and

surement is not representative and, when pos- frequency in people who drink plenty of cof-

sible, several should be made over 1–2 weeks. fee and tea.

Complete bladder emptying is important for ▶ Bladder retraining, whereby patients void by

avoiding recurrent urinary tract infections, the clock and voluntarily ‘hold on’ for increas-

maintaining upper urinary tract function and ingly longer periods, aims to restore the nor-

optimising the management of storage symp- mal pattern of micturition.

toms. As there are no effective medications for ▶ Pelvic floor exercises and neuromuscular stim-

improving voiding, catheterisation is usually the ulation may have a role, if voiding dysfunc-

best option. tion has been excluded, for ameliorating mild

Clean intermittent self-catheterisation is preferred symptoms.

as it avoids the long term complications asso-

ciated with a permanent indwelling catheter. Antimuscarinic medications competitively inhibit

However, the patient’s cognitive state, moti- acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors and improve

vation, manual dexterity and visual acuity are urgency, frequency and incontinence; their effect

important factors to consider. Frequency of cath- is by relaxing the detrusor muscle. Since the intro-

eterisation depends on the postvoid residual vol- duction of oxybutynin, several newer agents have

ume, detrusor pressure and fluid intake. been marketed (table 2) but the only significant

Reflex voiding using trigger techniques, and difference between them is their adverse effect

Credé’s manoeuvre (non-forceful, smooth even profi le.

pressure from the umbilicus towards the pubis), Adverse effects resulting from the non-specific

are usually not recommended as they may result anticholinergic action include dry mouth, blurred

in high detrusor pressures and incomplete bladder vision for near objects, tachycardia and consti-

emptying during voiding. pation. These drugs can also block central mus-

Suprapubic vibration using a mechanical ‘buzzer’ carinic M1 receptors and cause impairment in

has been demonstrated to be effective in MS cognition and consciousness in susceptible indi-

patients with incomplete bladder emptying and viduals; this might be mitigated by medications

detrusor overactivity, but its effect is limited. with low selectivity for the M1 receptor such as

α-Blockers relax the internal urethral sphincter darifenacin or restricted permeability across the

in men and there is evidence that they improve blood–brain barrier such as trospium.

bladder emptying and reduce postvoid residual Postvoid residual urine may increase following

volumes. However, this is not consistently seen in treatment and should be monitored by repeat blad-

clinical practice unless there is concomitant blad- der scans, especially if initial beneficial effects are

der outlet obstruction. short lasting. In many patients, there may also be

Botulinum toxin injections into the external ure- underlying voiding dysfunction and often it is the

thral sphincter may improve bladder emptying judicious combination of antimuscarinic medica-

in patients with spinal cord injury and significant tion with clean intermittent self-catheterisation

voiding dysfunction. which provides the most effective management

for neurogenic bladder dysfunction (figure 5).

Storage dysfunction Desmopressin, a synthetic analogue of arginine

Non-pharmacological measures are generally effec- vasopressin, temporarily decreases urine produc-

tive in the early stages when symptoms are mild. tion and volume determined detrusor overactivity

by promoting water reabsorption at the distal and

▶ Fluid intake of around 1–2 l a day, although collecting tubules of the kidney. It is useful for the

this should be individualised and it is often treatment of frequency or nocturia in conditions

helpful to assess fluid balance by means of a such as MS and spina bifida, providing symptom

bladder diary. free periods of up to 6 h. It is also helpful in man-

aging nocturnal polyuria which may be seen in

Parkinson’s disease and dysautonomia. However,

it should be prescribed with caution in patients

Table 2 Antimuscarinic medications available in the UK (presented alphabetically) over the age of 65 years or with dependant leg

Generic name Trade name Daily dose (mg) Frequency oedema, and should not be used more than once in

24 h for fear of hyponatraemia and heart failure.

Darifenacin Emselex 7.5–15 od

Botulinum toxin type A injected into the detrusor

Fesoterodine Toviaz 4–8 od

muscle under cystoscopic guidance appears to be

Oxybutynin immediate release Ditropan, cystrin 2.5–20 bd–qds

Oxybutynin ER Lyrinel XL 5–20 od

a highly promising, although as yet unlicensed,

Oxybutynin transdermal Kentera 36 mg (3.9 mg/24 h) One patch twice weekly

treatment for intractable detrusor overactivity.

Propantheline Pro-banthine 15–120 tds (1 h before food) Although patients often have to perform clean

Propiverine Detrunorm 15–60 od–qds intermittent self-catheterisation afterwards,

Solifenacin Vesicare 5–10 od the effect lasts 9–13 months and it significantly

Tolterodine immediate release Detrusitol 2–4 bd improves storage symptoms and quality of life.

Tolterodine extended release Detrusitol XL 4 od Patients have fewer urinary tract infections and

Trospium Regurin 20–40 bd (before food) reduced urethral leakage when using an indwell-

bd, twice daily; od, once daily; qds, four times daily; tds, three times daily. ing catheter (catheter bypassing).

2010;10:178–185. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.213892 183

Neurology in Practice

Sacral neuromodulation and posterior tibial nerve

stimulation can help manage neurogenic detru-

sor overactivity. The exact mechanism of action

remains unclear.

Surgical options such as augmentation cystoplasty

or urinary diversion are guided by discussions in

the setting of a multidisciplinary team, consider-

ing the degree of disability of the patient.

APPLIANCES AND EQUIPMENT

A range of continence aids such as penile sheaths

and disposable body worn pads may be helpful for

containing incontinence when other measures are

unsatisfactory. Men should be assessed and fitted

with external drainage systems if needed, and be

reviewed periodically. When appropriate, reuse-

able products such as pants and bed pads should

also be offered, as well as the full range of toilet-

ing equipment such as hand held urinals, aids and

portable commodes.

URINE INFECTION

▶ Urine should not be routinely tested unless

there are symptoms suggesting infection;

asymptomatic bacteriuria alone in a patient

performing clean intermittent self-catheteri-

sation is not an indication for antibiotics.

▶ Antibiotics should be limited to symptomatic

urinary tract infections.

▶ Unrestricted use of prophylactic antibiotics

can lead to drug resistance; however, in indi-

Figure 5 Algorithm for the management of neurogenic bladder dysfunction. viduals with proven recurrent urinary tract

Reproduced with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group (J Neurol Neurosurg infections in whom no urological structural

Psychiatry 2009;80:470–7). CISC, clean intermittent self-catheterisation; PVR, postvoid abnormality has been identified and whose

residual volume; UTI, urinary tract infection. intermittent catheterisation technique cannot

Figure 6 Stepwise approach to neurogenic bladder dysfunction management with progressing disability.

184 2010;10:178–185. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.213892

Neurology in Practice

Further reading Box 3 Red flags that suggest referral to a

specialist urology/urogynaecology service

▶ Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al.; Standardisation Sub-committee of the

International Continence Society. The standardisation of terminology of lower ▶ Haematuria

urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the ▶ Renal impairment

International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2002;21:167–78. ▶ Recurrent urinary tract infections

▶ Beck RO, Betts CD, Fowler CJ. Genitourinary dysfunction in multiple ▶ Bladder stones

system atrophy: clinical features and treatment in 62 cases. J Urol ▶ Pain thought to be arising from the urinary

1994;151:1336–41. tract

▶ Chapple CR, Khullar V, Gabriel Z, et al. The effects of antimuscarinic ▶ Suspicion of concomitant local pathologies such

treatments in overactive bladder: an update of a systematic review and as bladder outlet obstruction due to prostate

meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2008;54:543–62. enlargement in men, stress incontinence in

▶ DasGupta R, Fowler CJ. The management of female voiding dysfunction: women

Fowler’s syndrome—a contemporary update. Curr Opin Urol ▶ Symptoms refractory to treatment

2003;13:293–9. ▶ Consideration for intradetrusor injections of

botulinum toxin A

▶ DasGupta R, Kavia RB, Fowler CJ. Cerebral mechanisms and voiding

▶ Long term suprapubic catheterisation planned

function. BJU Int 2007;99:731–4.

▶ Consideration for surgery such as augmentation

▶ de Sèze M, Ruffion A, Denys P, et al.; GENULF. The neurogenic bladder in cystoplasty or urinary diversion

multiple sclerosis: review of the literature and proposal of management

guidelines. Mult Scler 2007;13:915–28.

▶ Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, de Groat WC. The neural control of micturition. Nat

Rev Neurosci 2008;9:453–66. drainage with a catheter valve, as opposed to

▶ Fowler CJ, Panicker JN, Drake M, et al. A UK consensus on the management continuous drainage into a leg bag, depends on

of the bladder in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry whether the bladder has a reasonable capacity to

2009;80:470–7. store urine.

Although most patients can be managed along

▶ Kalsi V, Gonzales G, Popat R, et al. Botulinum injections for the treatment of

these lines, there are specific situations where spe-

bladder symptoms of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2007;62:452–7.

cialist urology or urogynaecology services should

▶ Verhamme KM, Sturkenboom MC, Stricker BH, et al. Drug-induced be involved (box 3).

urinary retention: incidence, management and prevention. Drug Saf

2008;31:373–88.

CONCLUSIONS

▶ Lower urinary tract dysfunction is common

be improved, it is reasonable to start pro- in many neurological diseases and should be

phylactic low dose antibiotics; this decision medically manageable in most individuals.

should be taken in consultation with a urol- ▶ Evaluation requires assessment of storage dys-

ogy specialist team. function, voiding dysfunction, upper urinary

▶ The value of cranberry juice in preventing uri- tract integrity and infection.

nary tract infections is debatable. ▶ Postvoid residual urine greater than 100 ml

suggests significant voiding dysfunction and

STEPWISE APPROACH TO A PATIENT WITH clean intermittent self-catheterisation is the

treatment of choice.

NEUROGENIC BLADDER DYSFUNCTION

The treatment options should reflect the sever- ▶ Antimuscarinic medications are the main-

ity of the symptoms which generally parallel stay of treatment for the symptoms of storage

the extent of the neurological disease (figure 6). dysfunction.

However, beyond a certain point, the symptoms Acknowledgements This article was reviewed by Jan van Gijn,

may become refractory to all treatments and it is Utrecht, The Netherlands.

at this stage that a long term indwelling cathe- Provenance and peer review Commissioned; externally peer

ter should be offered. This should be a suprapu- reviewed.

bic rather than a urethral catheter because of the Competing interests CJF is the recipient of unrestricted educa-

impact of the latter on urethral integrity, peri- tional grants from Allergan and has also acted as a consultant for

neal hygiene and sexuality. Intermittent bladder Allergan and Medtronic.

2010;10:178–185. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.213892 185

You might also like

- Applications of Neurostimulation For Urinary Storage and Voiding Dysfunction in Neurological PatientsDocument6 pagesApplications of Neurostimulation For Urinary Storage and Voiding Dysfunction in Neurological PatientsMedranoReyesLuisinNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Bladder Dysfunction: Mariano Marcos State UniversityDocument6 pagesNeurogenic Bladder Dysfunction: Mariano Marcos State Universitychazney casianoNo ratings yet

- Consultation in Neurourology: A Practical Evidence-Based GuideFrom EverandConsultation in Neurourology: A Practical Evidence-Based GuideNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Bladder (Ayurveda Co-Relation)Document46 pagesNeurogenic Bladder (Ayurveda Co-Relation)Dr surendra A soniNo ratings yet

- Early Medical Treatment Prevents Renal Damage in Neurogenic BladderDocument9 pagesEarly Medical Treatment Prevents Renal Damage in Neurogenic BladderAMENDBENo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Bladder Dysfunction: Causes and ManagementDocument21 pagesNeurogenic Bladder Dysfunction: Causes and Managementretno widyastutiNo ratings yet

- Fowler 2008Document14 pagesFowler 2008Pablo IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Clothier-Wright2018 Article DysfunctionalVoidingTheImportaDocument14 pagesClothier-Wright2018 Article DysfunctionalVoidingTheImportaMarcello PinheiroNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Urinary Retention: Anesthetic and Perioperative ConsiderationsDocument19 pagesPostoperative Urinary Retention: Anesthetic and Perioperative Considerationspooria shNo ratings yet

- Neuropathic Bladder DisordersDocument12 pagesNeuropathic Bladder Disordershussain AltaherNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Dysfunction of The Lower Urinary TractDocument18 pagesNeuromuscular Dysfunction of The Lower Urinary TractArdian Sandhi PramestiNo ratings yet

- SplenectomyspringerDocument5 pagesSplenectomyspringerLuis CorderoNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of The Royal Society of Medicine: Can ADocument7 pagesProceedings of The Royal Society of Medicine: Can AAjeng EghaNo ratings yet

- Retencion Urinaria PosherniopDocument20 pagesRetencion Urinaria PosherniopFernando SaalNo ratings yet

- The Neural Control of MicturitionDocument29 pagesThe Neural Control of MicturitionPELVIC ANGELNo ratings yet

- Theneurogenicbladder: Anupdatewith Managementstrategies Forprimarycare PhysiciansDocument10 pagesTheneurogenicbladder: Anupdatewith Managementstrategies Forprimarycare Physicianschouko catNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Bladder (Emedicine) : Physiology Filling PhaseDocument4 pagesNeurogenic Bladder (Emedicine) : Physiology Filling PhaseReni FahrianiNo ratings yet

- NEUROGENIC BLADDER Nov 2021Document100 pagesNEUROGENIC BLADDER Nov 2021Ranjit SharmaNo ratings yet

- IT 16 - Neurogenic Bladder - SMDocument31 pagesIT 16 - Neurogenic Bladder - SMRurie Awalia SuhardiNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic BladderDocument8 pagesNeurogenic BladderrafendyfendyNo ratings yet

- OU SumberDocument5 pagesOU SumberAnggaNo ratings yet

- Voiding DysfunctionsDocument50 pagesVoiding DysfunctionsHemantNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic BladderDocument17 pagesNeurogenic BladderDina Shofiana FaniNo ratings yet

- Causes and Management of Obstructive NephropathyDocument11 pagesCauses and Management of Obstructive NephropathyMuchtar RezaNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Female LUTS: 1 Storage DysfunctionDocument10 pagesPathophysiology of Female LUTS: 1 Storage DysfunctionJaneva SihombingNo ratings yet

- Print PDFDocument16 pagesPrint PDFRobert ChristevenNo ratings yet

- Special Contribution 1 The Basics Behind Bladder Pain: A Review of Data On Lower Urinary Tract SensationsDocument7 pagesSpecial Contribution 1 The Basics Behind Bladder Pain: A Review of Data On Lower Urinary Tract SensationsAjeng Nanda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Bladder Innervation Physiology of Micturition Voiding DysfunctionDocument77 pagesBladder Innervation Physiology of Micturition Voiding DysfunctionKoushik Sharma AmancharlaNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Bladder: Mobility Clinic Case-Based Learning ModuleDocument11 pagesNeurogenic Bladder: Mobility Clinic Case-Based Learning ModuleJamaicaNo ratings yet

- HUMAN I ' A T I I O I . O G Y - V O L U M E 7, NUMBER 3 May 1976 - Myelination in the Neonatal BrainDocument5 pagesHUMAN I ' A T I I O I . O G Y - V O L U M E 7, NUMBER 3 May 1976 - Myelination in the Neonatal BrainsantiagoNo ratings yet

- Ude Part 4Document19 pagesUde Part 4Naresh DuthaluriNo ratings yet

- The Pancreas: Dr. Ali Kadhim Alhaider Consultant SurgeonDocument16 pagesThe Pancreas: Dr. Ali Kadhim Alhaider Consultant Surgeonhussain AltaherNo ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal Dysfunction in Parkinson's DiseaseDocument5 pagesGastrointestinal Dysfunction in Parkinson's DiseaseAlem TuzumabNo ratings yet

- C+F-Urinary Incontinence in Dogs and Cats - Part II. Diagnosis and ManagementDocument11 pagesC+F-Urinary Incontinence in Dogs and Cats - Part II. Diagnosis and Managementtaner_soysuren100% (2)

- LutsDocument24 pagesLutsJaneva SihombingNo ratings yet

- Acute Urinary Retention Pathways and CausesDocument26 pagesAcute Urinary Retention Pathways and Causeslukmankyubi100% (1)

- COVID-19 Targets Lower Medulla Oblongata Via Vagus NerveDocument2 pagesCOVID-19 Targets Lower Medulla Oblongata Via Vagus NerveBOHR International Journal of Current research in Dentistry (BIJCRID)No ratings yet

- Urinary Incontinence: Genet Gebremedhin (MD) April 4 2017Document34 pagesUrinary Incontinence: Genet Gebremedhin (MD) April 4 2017bemnetNo ratings yet

- Neurourology Online Class 26-6-20Document281 pagesNeurourology Online Class 26-6-20akish4uNo ratings yet

- Neurophysiology of Swallowing: Cumhur Ertekin, Ibrahim AydogduDocument19 pagesNeurophysiology of Swallowing: Cumhur Ertekin, Ibrahim AydogduValentina SalasNo ratings yet

- Sick Growing Child: Hirschsprung Disease Anorectal Malformation Maluenda CamilleDocument46 pagesSick Growing Child: Hirschsprung Disease Anorectal Malformation Maluenda CamilleCamille Maluenda - TanNo ratings yet

- Kanai-2010-Bladder Afferent Signaling - Recent FindingsDocument13 pagesKanai-2010-Bladder Afferent Signaling - Recent Findingssachjoe33No ratings yet

- Neurogenic BladderDocument28 pagesNeurogenic Bladderbhatubim100% (2)

- Neurogenic Bladder-: Detrusor Muscle Transitional EpitheliumDocument4 pagesNeurogenic Bladder-: Detrusor Muscle Transitional EpitheliumMiriam Saena EscarlosNo ratings yet

- RenalDocument34 pagesRenalSaily JaquezNo ratings yet

- Benzing-2021-Insights Into Glomerular FiltrationDocument10 pagesBenzing-2021-Insights Into Glomerular FiltrationNguyen LequyenNo ratings yet

- Types and Causes of Urinary IncontinenceDocument9 pagesTypes and Causes of Urinary Incontinencehussain AltaherNo ratings yet

- Broodbank & Christian. Renal Tubular Disorders. 2018.Document10 pagesBroodbank & Christian. Renal Tubular Disorders. 2018.Jéssica Hilário BonomoNo ratings yet

- Insight Into Glomerular Filtration and Albuminuria - NEJMDocument10 pagesInsight Into Glomerular Filtration and Albuminuria - NEJMasalizwa ludlalaNo ratings yet

- Power Doppler Sonographic Diagnosis of Torsion in A Wandering SpleenDocument3 pagesPower Doppler Sonographic Diagnosis of Torsion in A Wandering SpleendenisegmeloNo ratings yet

- Urogenital Symptoms in Neurologic Patients.14Document20 pagesUrogenital Symptoms in Neurologic Patients.14Fawad JanNo ratings yet

- Acute GlomerulonephritisDocument1 pageAcute GlomerulonephritisAyrheen FornolesNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Causes of Dysphagia ExplainedDocument5 pagesNeurogenic Causes of Dysphagia ExplainedRocioBelénAlfaroUrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Neuro UrologyDocument53 pagesNeuro UrologymoominjunaidNo ratings yet

- Canine Urinary IncontinenceDocument9 pagesCanine Urinary IncontinenceAsesino GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Physiology of Urine Formation and Micturition-1Document52 pagesPhysiology of Urine Formation and Micturition-1Himani RanaNo ratings yet

- BladderDocument66 pagesBladderPatel Alapkumar Kanubhai100% (1)

- News & Views: Non-Canonical Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway in IBDDocument2 pagesNews & Views: Non-Canonical Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway in IBDJesus HuaytaNo ratings yet

- Sir 2014 SouthamericaDocument33 pagesSir 2014 SouthamericahusseinNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Nursing 6th Edition Keltner Test BankDocument35 pagesPsychiatric Nursing 6th Edition Keltner Test Bankfrustumslit.4jctkm100% (26)

- The Nature of Feeding and Swallowing Difficulties in PDFDocument118 pagesThe Nature of Feeding and Swallowing Difficulties in PDFLisa NurhasanahNo ratings yet

- 116 Draft OilsDocument233 pages116 Draft OilsMarcela Paz Gutierrez UrbinaNo ratings yet

- Mumps Guide: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment & PreventionDocument14 pagesMumps Guide: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment & PreventionChristian JonathanNo ratings yet

- Project WorkPlan Budget Matrix ENROLMENT RATE SAMPLEDocument3 pagesProject WorkPlan Budget Matrix ENROLMENT RATE SAMPLEJon Graniada60% (5)

- Pulse Oximetry: Review Open AccessDocument7 pagesPulse Oximetry: Review Open AccessAlain SoucotNo ratings yet

- Nematode EggsDocument5 pagesNematode EggsEmilia Antonia Salinas TapiaNo ratings yet

- LESSON 1 and LESSON 2Document5 pagesLESSON 1 and LESSON 21234567werNo ratings yet

- BSN 3G GRP 4 Research TitlesDocument6 pagesBSN 3G GRP 4 Research TitlesUjean Santos SagaralNo ratings yet

- Health Education Plan-DiarrheaDocument10 pagesHealth Education Plan-DiarrheaMae Dacer50% (2)

- Enalapril Maleate TabletsDocument2 pagesEnalapril Maleate TabletsMani SeshadrinathanNo ratings yet

- Atwwi "Virtual" Trading Room Reference Document November 2, 2020Document4 pagesAtwwi "Virtual" Trading Room Reference Document November 2, 2020amisamiam2No ratings yet

- Complications of Caesarean Section: ReviewDocument8 pagesComplications of Caesarean Section: ReviewDesi Purnamasari YanwarNo ratings yet

- Hazard Full SlideDocument31 pagesHazard Full SlideRenKangWongNo ratings yet

- Education Region III Tests Climate ChangeDocument6 pagesEducation Region III Tests Climate ChangeLiezl SabadoNo ratings yet

- Start and Run Sandwich and Coffee Shops PDFDocument193 pagesStart and Run Sandwich and Coffee Shops PDFsap7e88% (8)

- Ayurveda Medical Officer 7.10.13Document3 pagesAyurveda Medical Officer 7.10.13Kirankumar MutnaliNo ratings yet

- Debona 2016Document23 pagesDebona 2016Biomontec Biomontec BiomontecNo ratings yet

- Improving Healthcare Quality in IndonesiaDocument34 pagesImproving Healthcare Quality in IndonesiaJuanaNo ratings yet

- Schedule - Topnotch Moonlighting and Pre-Residency Seminar Nov 2022Document2 pagesSchedule - Topnotch Moonlighting and Pre-Residency Seminar Nov 2022Ala'a Emerald AguamNo ratings yet

- Declaration of Erin EllisDocument4 pagesDeclaration of Erin EllisElizabeth Nolan BrownNo ratings yet

- ESHRE IVF Labs Guideline 15122015 FINALDocument30 pagesESHRE IVF Labs Guideline 15122015 FINALpolygone100% (1)

- Al Shehri 2008Document10 pagesAl Shehri 2008Dewi MaryamNo ratings yet

- Nursing Acn-IiDocument80 pagesNursing Acn-IiMunawar100% (6)

- Measurement of Physical Fitness and Physical Activity. Fifty Years of Change 3PDocument12 pagesMeasurement of Physical Fitness and Physical Activity. Fifty Years of Change 3PMuhd NashhanNo ratings yet

- Csa Fodrea 2014 - 2015 Student Handbook FinalDocument37 pagesCsa Fodrea 2014 - 2015 Student Handbook Finalapi-260407035No ratings yet

- Understanding Narcolepsy: Symptoms, Causes and TreatmentsDocument2 pagesUnderstanding Narcolepsy: Symptoms, Causes and TreatmentsAl Adip Indra MustafaNo ratings yet

- The Holy Grail of Curing DPDRDocument12 pagesThe Holy Grail of Curing DPDRDany Mojica100% (1)

- Psihogeni Neepileptički Napadi Kao Dijagnostički Problem: AutoriDocument4 pagesPsihogeni Neepileptički Napadi Kao Dijagnostički Problem: AutorifhdhNo ratings yet

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (78)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsNo ratings yet

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementFrom EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (40)

- Daniel Kahneman's "Thinking Fast and Slow": A Macat AnalysisFrom EverandDaniel Kahneman's "Thinking Fast and Slow": A Macat AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (130)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (34)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (327)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassFrom EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (21)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingFrom EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (31)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)