Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Renewed Push For A Con-Con

Uploaded by

C. Mitchell ShawOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Renewed Push For A Con-Con

Uploaded by

C. Mitchell ShawCopyright:

Available Formats

by Joe Wolverton II, J.D.

T

here is an alarming increase in the number and

volume of otherwise credible conservative voices

clamoring for the state governments to call a consti-

tutional convention per the provisions set forth in Article

V of the U.S. Constitution.

We begin this examination of the dangers posed by such

a convention by laying out the constitutional authority re-

lied upon by its advocates. Article V in relevant part:

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses

shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments

to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Leg-

islatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call

a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in

either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes,

as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Leg-

islatures of three fourths of the several States or by

Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or

the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by

the Congress.

The Goldwater Institute recently published a three-part

paper entitled Amending the Constitution by Convention:

A Complete View of the Founders Plan by Robert G. Na-

telson. The paper is seemingly intended to function as a

tract for use to convert other conservatives to the cause of

the constitutional convention as a remedy to runaway big

government. The Executive Summary of Part 1 by Nick

Dranias asserts that under Article V, the states have the

power to apply to Congress to hold a convention for the

purpose of proposing constitutional amendments. This

power was meant to provide a fail-safe mechanism to con-

trol the federal government.

Fedgov Powers Few and Defined

There is a fundamental error in this statement: The Con-

stitution does not grant to the states any powers. On

the contrary, the Constitution is the delegation by the

sovereign states to the central (federal) government of a

few and definite powers. The nature of this relationship

is best described in The Federalist, No. 45, by James

Madison:

The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution

to the federal government are few and defined. Those

which are to remain in the State governments are nu-

merous and indefinite.

There is another flaw in Dranias Executive Summary re-

garding the power of Article V, and it effectively impedes

the Goldwater Institutes march toward a new constitution-

al convention. Simply put, the black letter of Article V does

not allow for a convention with any purpose other than

proposing amendments, which if ratified by the states

(by either of the two methods provided) would become

part of [the] Constitution. Why would a constitutionalist,

sincere in his desire to restore the proper balance between

Calls for a Constitutional Convention are exercises in misdirection. The Constitution

doesnt need fixing; government officials who violate it need to be removed.

Renewed Push for a Con-Con

Whom do you trust: The Founders who gave us our

incomparable Constitution, or our current spendthrift politicians

who want to rewrite our governing compact?

www.TheNewAmerican.com 27

CONSTITUTION CORNER

the state and national governments, advocate a convention to

propose amendments to a Constitution that, according to both

its authors and its plain language, already protects that delicate

and unique balance of power between the states and the federal

government? Is our Constitution as presently written silent or

unclear on the subject of the rightful boundaries separating those

two entities? In fact, it is not and therefore we do not need to

incur the risk of upsetting that balance or erasing those bound-

aries by convening an Article V constitutional convention for

that purpose.

Constitutional Remedy: Enforce the Constitution

The truth is that a call for a new constitutional convention under

such auspices is contrary to the very spirit of rigidly hewing to

the text of the Constitution (including the related concept of

limited, enumerated powers) that animates friends of our Re-

public to struggle steadfastly against usurpations by the national

government. We do not need a new constitutional convention if

our legitimate aim is to reaffirm the principles already clearly

set forth in our current Constitution.

In other pieces published to support its call for a constitu-

tional convention, the Goldwater Institute points to the end-

less growth of the federal government as the impetus for the

crescendo of cries for a new constitutional convention to re-

gain control over the federal government. Again, the Con-

stitution is not the problem, so the remedy cannot be found

in changing or amending it. In fact, it is the Constitution as

presently written that serves as the first, final, and most pow-

erful check on the unwieldy expansion of the scope of federal

influence. In any event, until such time as the Constitution

is faithfully followed, there is no reason to believe that any

amendment passed at an Article V constitutional convention

would not be ignored, misinterpreted, and violated as badly

as existing clauses to justify the federal governments unre-

pentant encroachment into the lives of Americans and into the

sovereignty of the states.

Besides, the Constitution already specifically and explicitly

grants only very limited powers to the national government and

thus what we need is not a new constitutional convention, but

a restoration of constitutional boundaries. This retrenchment is

most ably accomplished through state nullification of the so-

called laws passed by Congress, and by the refusal by consti-

tutionally minded Congressmen to vote for the funding of any

unconstitutional expenditures or the exercise of any power not

enumerated or logically implied by the Constitution.

The second plank in the Goldwater Institutes Article V con-

vention platform is the historical record. It contends that the

conventions held in Annapolis in September 1786 and Phila-

delphia in the summer of 1787 did not exceed their mandates,

and cites them as evidence that a constitutional convention can

accomplish great good with only limited scope. These were not

Article V conventions. Natelson claims that neither of those

conventions was a runaway convention and that the record

supports this interpretation of the broad powers granted by

state commissions carried by the delegates to those conven-

tions. That account of those seminal events is not completely

accurate.

A core premise of the Institutes conclusion is that neither

the Annapolis Convention nor the Constitutional Convention

of Philadelphia exceeded its mandate. The report claims that,

48 of the 55 delegates [to the Philadelphia Convention] had

instructions which allowed them to go beyond amending the

Articles of Confederation. To assert, then, that the Constitu-

tional Convention was not runaway with regard to those 48

delegates is arguably true. However, what of the seven delegates

whose commissions expressly forbade them from ratifying, or

even participating in, any proposal calling for the dismantling of

the government created by the Articles of Confederation? What

of the states represented by those delegates? Yet after ratifica-

tion of the Constitution crafted in Philadelphia, the citizens and

governments in those states were equally bound to abide by the

terms of that contract.

We do not need a new constitutional convention.

What we need is a return to the principles of

federalism, limited government, enumerated

powers, and popular sovereignty already a part

of our existing Constitution.

Violating a sacred oath: All members of Congress swear to uphold

and defend the Constitution, but many (if not most) of their votes

violate the letter and spirit of that document.

CONSTITUTION CORNER

THE NEW AMEPCAN * APPL 18, 2011 28

By logical extension, then, all the states would be equally

bound by the amendments passed by delegates to a new consti-

tutional convention called for under Article V.

Another relevant point regarding those early conventions is

that while it is true that nothing of any revolutionary import

was accomplished at Mt. Vernon or the convention at Annapolis,

the hope of several of the key participants (Washington, Madi-

son, and Hamilton, principally) in those conventions was that

the convention in Philadelphia would not be hampered by the

temporizing or partial remedies that hamstrung the previous

attempts at establishing a more dynamic central authority. These

great statesmen were frustrated that their new Rome was burn-

ing while the Neros in the Confederation Congress fiddled with

half measures that did nothing more noble than protect their own

petty seats of power.

Those familiar with the history of the early Republic know

that violent centrifugal forces (including the literal burning of

courthouses in Massachusetts and Richmond, Virginia) were

throwing into sudden reverse the centripetal attraction that unit-

ed the colonies in their war against the British crown. The newly

independent states were flung into a chaotic destabilizing mael-

strom of disaffection, debt, and outright armed rebellion against

state governments and the embryonic (though already impotent)

central authority created by the Articles of Confederation.

This post-bellum agitation was worrisome to many of our

young nations leading lights. George Washington, James Madi-

son, and Alexander Hamilton in particular were dismayed to see

the goodwill deposited into the account of union after the War

for Independence being prodigally spent to quash internecine

uprisings of Americans against Americans. They rightly wor-

ried that this disunion would result in the fracture of the United

States into two or more smaller confederacies.

It is a matter of historical record that many of our nations

Founding Fathers revealed in their personal correspondence

their private aspirations for the meetings to be held in Mt. Ver-

non and Annapolis. James Madison and George Washington in

particular express in letters to each other and to other correspon-

dents that they hoped for a convention wherein the delegates

would come with plenary power to establish a new government.

In fact, George Washington wrote that he feared that if the dele-

gates come to it [the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia]

under fetters, the salutary ends proposed will in my opinion be

greatly embarrassed and retarded, if not altogether defeated.

While we rightly admire Washington, Madison, Hamilton, et

al., it is more for what they did than how they did it. If we are

intellectually honest with ourselves, we must admit that while

there was perhaps no active, knowing dissembling in the calling,

convening, and conducting of the conventions (including Phila-

delphia) that produced the Constitution we hold so dear, there

was certainly a committed effort by these movers of men to fly

a stronger national government under the sweep of the vigilant

radar of Congress and the states.

Who Would Our New Founders Be?

We are fortunate that the ulterior motives of the generation of

statesmen who crafted our Constitution were noble, altruistic, and

consistent with timeless principles of liberty and limited republi-

can self-government. Were we to answer the call for the conven-

ing of a modern constitutional convention, what manner of men

and women would attend it and would their goals be as honorable

and praiseworthy as those set by our Founding Fathers?

It is unlikely. Moreover, there is no constitutional mechanism

for controlling who would be selected as delegates to such a

convention. Radical factions of every stripe would jockey to at-

tend, slavering over the opportunity to tweak this or that aspect

of the Constitution to suit their respective political or socioeco-

nomic philosophies. Or, perhaps they would decide it would

be easier to scrap the old document altogether and just begin

anew which is exactly what happened when the Articles of

Confederation were cast aside in favor of an entirely new Con-

stitution. The accomplishment of the Convention of 1787 could

rightly be called a miracle, but what would prevent a modern-

day convention from becoming a nightmare? The prospect of a

convention endowed with power of this magnitude, populated

by delegates determined to tinker with the precision gears that

give movement to works of our mighty Republic, is frighten-

ing and should give pause to everyone presently promoting this

cause or considering joining in it.

Also, what are the chances that the representatives chosen to

deliberate these heady matters would be men of character and

wisdom who understand and support minimal government and

the division of powers under the Constitution? Will we be twice

blessed with an assembly of demigods? How many such men

can actually be found in any of our modern-day councils

and how many of them would actually be selected as conven-

tion delegates? Even if Providence were to guide every step of

"1*NBHFT

29 Ca|| 1-800-727-TPUE to suLscriLe toay!

this perilous process and the delegates selected were people of

the sort who built our present system, the wise words of James

Madison must be remembered and pondered in this regard: Had

every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assem-

bly would still have been a mob.

Furthermore, despite the r eassurance of the proponents of a

new constitutional convention, tradition can be no reliable guide

in this area as there are no immovable metes and bounds to

which participants must adhere. Their theory works well in a

vacuum, but in the real world of politics and lobbyists, there

is real danger of the destruction of the Constitution even,

as Roger Sherman warned his colleagues in the Philadelphia

Convention, unto the abolition of state sovereignty altogether.

A related historical problem is that in the propaganda pub-

lished to support the call for an Article V convention, advocates

interpret far too liberally the language of the documents granting

agency to delegates to the conventions held earlier in our history.

To argue, for example, that the authorization given by the state

of Georgia to its representatives to effect all such Alterations

and farther Provisions as may be necessary to render the Federal

Constitution adequate to the exigencies of the Union granted

them broad, unshackled power to work to create a new constitu-

tion stretches the bounds of defensible exegesis and reads like

convenient casuistry.

The averment, for example, that the phrase Federal Consti-

tution as used by Georgia was simply the 18th-century way

of defining the entire political system (such as is typically

applied to the much-heralded unwritten constitution of the

United Kingdom) would be more persuasive if at the time of

the drawing of that document there was not a written federal

constitution in legal effect. As susceptible to well-founded and

legitimate criticism the Articles of Confederation were, the un-

avoidable fact is that on the day the Georgia delegates were

handed the parchment approving their attendance at the Phila-

delphia Convention in May, they were living under a legally

operable and binding federal constitution.

One of the most self-serving of the errors contained in Na-

telsons Part 1 published by the Goldwater Institute is that of

assuming the basis of its opponents argument. The document

supposes that those constitutionalists who fear a modern-day

runaway convention base their case on the wording of the Con-

federation Congressional resolution recommending that states

send commissions to the convention to be held in May of 1787

in Philadelphia.

Runaway Reality

Specifically, Natelson and his allies erect the straw man of the

aforementioned resolution in order to prove that the attendees at

the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention did not exceed the

express authority granted them by their respective state govern-

ments. (The resolution proposed that a convention be held for

the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confed-

eration.) On the contrary, those who oppose an Article V con-

vention are as aware as those on the other side of the issue that

the resolution passed by the Confederation Congress was of no

more than persuasive legal authority. It is the instructions given

by the states to their agents, the delegates, that hold the key to

whether or not the convention held in Philadelphia in 1787 was

runaway or not.

In actuality, those aligned against the call for an Article V

convention are as familiar as Natelson with the purposes and

prejudices of states and the men sent by them to protect their

interests at the Constitutional Convention.

Finally, there is one salient point that is ignored by Natelson

in his use of the accounts of historical conventions to quell

the fears of those yet wary of what might happen at a modern

convention.

Even if one assumes for the sake of argument that there was

One tyranny for another? Did our Founding generation declare independence from the tyranny of the British crown only to have us accept a new

tyranny from federal overlords in Washington, D.C.?

THE NEW AMEPCAN * APPL 18, 2011 30

CONSTITUTION CORNER

To Order

(800) 727-8783

www.TheNewAmerican.com

An effective educational tool to inform

others about national and world events

Recipient is reminded of your generosity

throughout the year

Just $39 per gift subscription

Give the gift of

TRUTH

A Republic,

If You Can Keep It

Appleton, WI 54912-8040 (920) 749-3780

Less government, more responsibility, and with Gods help a better world.

nothing runaway about the Annapolis or Philadelphia conven-

tions and that the delegates that attended those meetings rigidly

adhered to a narrowly tailored agenda of limited scope, that as-

sumption is immaterial in the discussion of the potential dangers

of an Article V convention.

The simple, material, and irrefutable fact is that Article V did

not exist when those earlier meetings convened and therefore

neither the agenda nor the legally permissible outcome were

governed by the provisions thereof. One cannot convincingly

argue that a convention called under other auspices and other

authority, all of which predated the current Constitution, would

be at all binding on the procedure or purpose of a constitutional

convention called according to the mandates of Article V.

In spite of their many historical errors and mistakes in judg-

ment, many of those proselytizing for an Article V convention are

very convincing. One is reminded of the words of King Agrippa,

when confronted with the compelling arguments of St. Paul, Al-

most thou persuadest me. Alas, however, we are not persuaded.

Indisputably, every American worthy of the label constitu-

tionalist agrees with the position that the federal government

has obliterated the barriers placed by the Constitution of 1787

around its very limited powers. Furthermore, we all agree that

the time has come for very drastic measures to be employed if

we are to rescue our beloved Republic from the brink of absolut-

ism upon which it is now precariously hanging.

THE NEW AMERICAN (and The John Birch Society) part com-

pany with the Goldwater Institute, Robert Natelson, and their

companions, however, in the way such salvation is to be best

accomplished. In our view, we do not need a new constitutional

convention, regardless of how limited in scope it may claim to

be. What we need is a return to the principles of federalism, lim-

ited government, enumerated powers, and popular sovereignty

already a part of our existing Constitution.

We are not persuaded that such a convention would conform

to restraints or limits placed upon it by the states or Congress.

Even the Goldwater Institutes own paper admits that, abuses

of the Article V constitutional amendment process are possible.

Given the ready availability of the salubrious and side-effect free

remedy of returning to the principles of the Constitution as pres-

ently established, there is no need to assume the risks inherent

in such possible abuses and the fatal side effects that may ac-

company the radical treatment of a new convention. The cure, in

this case, would almost certainly be worse than the disease. The

fate of our nation and our Constitution hangs in the balance. Q

You might also like

- The Decline of the Constitutional Government in the United States: A "Declaration of True Meaning" Procedure Could Help the People to Restore ItFrom EverandThe Decline of the Constitutional Government in the United States: A "Declaration of True Meaning" Procedure Could Help the People to Restore ItRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Constitutional Law: The ConstitutionDocument8 pagesConstitutional Law: The ConstitutioncryziaNo ratings yet

- Federal JurisdictionDocument13 pagesFederal JurisdictionDennis T.100% (2)

- Administrative Agencies - The Fourth Branch of GovernmentDocument10 pagesAdministrative Agencies - The Fourth Branch of Governmentsleepysalsa100% (1)

- The U.S. Constitution and Money Part 4 The First and Second Banks of The United StatesDocument39 pagesThe U.S. Constitution and Money Part 4 The First and Second Banks of The United Statesmichael s rozeffNo ratings yet

- The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United StatesFrom EverandThe Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The Silver BulletinDocument14 pagesThe Silver BulletinI have rejoined myself with the cause by Charles W. Iseley/Isley for personal reasons. I'll follow the Sun.100% (1)

- The President's Veto PowerDocument24 pagesThe President's Veto PowerSteven YanubiNo ratings yet

- Primary Source - Hamilton vs. Jefferson - National BankDocument4 pagesPrimary Source - Hamilton vs. Jefferson - National BankJess ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- State Sovereignty CRS Report 2008Document29 pagesState Sovereignty CRS Report 2008Jim Neubacher100% (1)

- Charter ChangeDocument11 pagesCharter ChangeMarivic SorianoNo ratings yet

- Section 10 Powers Denied to StatesDocument4 pagesSection 10 Powers Denied to StatesJusticeNo ratings yet

- How to Write an Effective AffidavitDocument4 pagesHow to Write an Effective AffidavitRonnieEngging100% (1)

- I, Pencil: My Family Tree As Told To Leonard E. ReadDocument17 pagesI, Pencil: My Family Tree As Told To Leonard E. ReadWillianTian100% (4)

- States Should Enforce Not Revise The ConstitutionDocument8 pagesStates Should Enforce Not Revise The ConstitutionJBSfan100% (1)

- Grit The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDocument1 pageGrit The Power of Passion and PerseveranceAde Oriflame0% (3)

- Instant Download Marriages Families and Relationships Making Choices in A Diverse Society 11th Edition Lamanna Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Marriages Families and Relationships Making Choices in A Diverse Society 11th Edition Lamanna Test Bank PDF Full ChapterKellyBellkrgx100% (4)

- Authorization LetterDocument2 pagesAuthorization LetterCraze AhmedNo ratings yet

- Form LRA 87Document2 pagesForm LRA 87Godfrey ochieng modi67% (3)

- Irena Sendler: Humble Holocaust HeroineDocument6 pagesIrena Sendler: Humble Holocaust HeroineC. Mitchell ShawNo ratings yet

- in Re Will of Rev. Abadia (Dumlao)Document1 pagein Re Will of Rev. Abadia (Dumlao)Luntian Dumlao100% (1)

- Joint Affidavit of Two Disinterested PartiesDocument1 pageJoint Affidavit of Two Disinterested PartiesKristine JanNo ratings yet

- Wills Case ListDocument6 pagesWills Case ListJ Rachelle PaezNo ratings yet

- De Leon v. Esguerra (Autonomy of Barangays)Document19 pagesDe Leon v. Esguerra (Autonomy of Barangays)kjhenyo218502No ratings yet

- 23-Olivares Vs MarquezDocument2 pages23-Olivares Vs MarquezCyrus Santos Mendoza100% (1)

- 10PointRefutation TNA2707Document4 pages10PointRefutation TNA2707C. Mitchell ShawNo ratings yet

- 2013oct7 - Levins Risky ProposalDocument6 pages2013oct7 - Levins Risky ProposalkrypticnetNo ratings yet

- AT Constitutional Convention CP - Northwestern 2015Document13 pagesAT Constitutional Convention CP - Northwestern 2015Michael TangNo ratings yet

- All About Usa ConstitutionDocument11 pagesAll About Usa Constitutionkaransinghania615No ratings yet

- The Consent of the Governed: Popular Sovereignty and Constitutional Amendment Outside Article VDocument52 pagesThe Consent of the Governed: Popular Sovereignty and Constitutional Amendment Outside Article VJesús María Alvarado AndradeNo ratings yet

- DBQ #1Document3 pagesDBQ #1Kartik Dhinakaran0% (2)

- Instant Download Investments 11th Edition Bodie Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Investments 11th Edition Bodie Solutions Manual PDF Full Chaptercrapevioloush1o100% (6)

- Formal and Informal Amendment of The United States ConstitutionDocument27 pagesFormal and Informal Amendment of The United States ConstitutionPrankrishna SaikiaNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Physics For Scientists and Engineers Foundations and Connections 1st Edition Katz Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Physics For Scientists and Engineers Foundations and Connections 1st Edition Katz Solutions Manual PDF Full Chaptergenericparaxialb41vmq100% (4)

- Stop The Article V Convention by Peter BoyceDocument6 pagesStop The Article V Convention by Peter BoyceHal ShurtleffNo ratings yet

- Gary Lawson - Rise and Rise of The Adm State - HavLRevDocument6 pagesGary Lawson - Rise and Rise of The Adm State - HavLRevAOSBS100% (1)

- Instant Download Cornerstones of Managerial Accounting Mowen 5th Edition Test Bank PDF ScribdDocument32 pagesInstant Download Cornerstones of Managerial Accounting Mowen 5th Edition Test Bank PDF ScribdNancyGarciakprq100% (13)

- Instant Download Practice of Nursing Research Appraisal Synthesis and Generation of Evidence 7th Edition Grove Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument33 pagesInstant Download Practice of Nursing Research Appraisal Synthesis and Generation of Evidence 7th Edition Grove Test Bank PDF Full Chaptersiennamurielhlhk100% (5)

- Instant Download Strategic Management Concepts and Cases Arab World 1st Edition David Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument33 pagesInstant Download Strategic Management Concepts and Cases Arab World 1st Edition David Test Bank PDF Full ChapterTylerKochpefd100% (6)

- Full Download Test Bank For Fundamental Nursing Skills and Concepts Tenth Edition PDF FreeDocument32 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Fundamental Nursing Skills and Concepts Tenth Edition PDF FreePaul Lafferty100% (9)

- MAKASIAR ConcurringDocument7 pagesMAKASIAR ConcurringBrian Kelvin PinedaNo ratings yet

- Full Download Test Bank For Foundations of Nursing 8th Edition PDF FreeDocument32 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Foundations of Nursing 8th Edition PDF FreeLowell Garcia100% (12)

- Hamilton On BankDocument32 pagesHamilton On Bankreader_jimNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Principles and Labs For Fitness and Wellness 13th Edition Hoeger Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Principles and Labs For Fitness and Wellness 13th Edition Hoeger Test Bank PDF Full ChapterSallyRobertscmnq100% (5)

- ConLaw NotesDocument57 pagesConLaw NotesEmily DriscollNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Human Resource Management Functions Applications and Skill Development 2nd Edition Lussier Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument33 pagesInstant Download Human Resource Management Functions Applications and Skill Development 2nd Edition Lussier Solutions Manual PDF Full Chaptercoilwheyb7wsk100% (6)

- Reserved Powers of The States: Significant CasesDocument5 pagesReserved Powers of The States: Significant CasesJonahs gospel100% (1)

- Instant Download Solution Manual For Programming With Microsoft Visual Basic 2015 7th Edition PDF ScribdDocument32 pagesInstant Download Solution Manual For Programming With Microsoft Visual Basic 2015 7th Edition PDF Scribdpointerreddour17ocj100% (10)

- Remarks of Mr. Calhoun of South Carolina on the bill to prevent the interference of certain federal officers in elections: delivered in the Senate of the United States February 22, 1839From EverandRemarks of Mr. Calhoun of South Carolina on the bill to prevent the interference of certain federal officers in elections: delivered in the Senate of the United States February 22, 1839No ratings yet

- Instant Download Management Australia 7th Edition Stagg Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument33 pagesInstant Download Management Australia 7th Edition Stagg Test Bank PDF Full Chapteryearaastutecalml100% (8)

- Five Myths Concerning Article VDocument2 pagesFive Myths Concerning Article VkrypticnetNo ratings yet

- Full Download Ebook PDF Fundamentals of Biostatistics 8Th Edition Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full ChapterDocument22 pagesFull Download Ebook PDF Fundamentals of Biostatistics 8Th Edition Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full Chapterbernice.shultz383100% (28)

- Federalism and the Separation of Powers ExplainedDocument25 pagesFederalism and the Separation of Powers ExplainedJosefinaGomezNo ratings yet

- Unit II Congressional District Questions Q1: How Does The Constitution Limit Government Power To Protect Individual Rights While Promoting The Common Good?Document10 pagesUnit II Congressional District Questions Q1: How Does The Constitution Limit Government Power To Protect Individual Rights While Promoting The Common Good?api-298524731No ratings yet

- WHAT IN THE CONSTITUTION CANNOT BE AMENDED? 23 ARIZONA LAW REVIEW 717 (Footnotes Have Been Omitted.) by Douglas LinderDocument7 pagesWHAT IN THE CONSTITUTION CANNOT BE AMENDED? 23 ARIZONA LAW REVIEW 717 (Footnotes Have Been Omitted.) by Douglas LinderSFLDNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Life Span Development Canadian 6th Edition Santrock Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Life Span Development Canadian 6th Edition Santrock Solutions Manual PDF Full Chapterrobertreynoldsosgqczbmdf100% (4)

- Formal and Informal Amendment of The United States ConstitutionDocument37 pagesFormal and Informal Amendment of The United States ConstitutionRezky Amalia SyafiinNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Solution Manual For Supply Chain Management 7th Edition Sunil Chopra PDF ScribdDocument32 pagesInstant Download Solution Manual For Supply Chain Management 7th Edition Sunil Chopra PDF Scribdtylernelsonmorkzgintj100% (11)

- Parens PatriaeDocument12 pagesParens Patriaeagray43No ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument15 pagesUntitled DocumentArchana BhartiNo ratings yet

- Consitution of Usa1Document124 pagesConsitution of Usa1e videosNo ratings yet

- Congress: Chapter OutlineDocument42 pagesCongress: Chapter OutlineRaven BennettNo ratings yet

- Amendment Process in USA and Switzerland Roshni Thammaiah NotesDocument11 pagesAmendment Process in USA and Switzerland Roshni Thammaiah NotesRoshni ThammaiahNo ratings yet

- The Constitution Why A Constitution?Document1 pageThe Constitution Why A Constitution?dbraziulyteNo ratings yet

- Amending The Constitution - Boundless Political ScienceDocument14 pagesAmending The Constitution - Boundless Political ScienceAdriana InomataNo ratings yet

- Full Download Test Bank For Computer Accounting With Quickbooks 2019 19th Edition Donna Kay PDF Full ChapterDocument33 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Computer Accounting With Quickbooks 2019 19th Edition Donna Kay PDF Full Chapterdiesnongolgothatsczx100% (13)

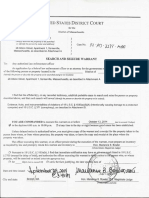

- Marty Gottesfeld Search WarrantDocument8 pagesMarty Gottesfeld Search WarrantC. Mitchell ShawNo ratings yet

- Marty Gottesfeld Tap and Trace OrderDocument10 pagesMarty Gottesfeld Tap and Trace OrderC. Mitchell ShawNo ratings yet

- Federal Enumerated PowersDocument4 pagesFederal Enumerated PowersC. Mitchell ShawNo ratings yet

- STOPACon ConActionSheet2010 2011 1Document2 pagesSTOPACon ConActionSheet2010 2011 1C. Mitchell ShawNo ratings yet

- Understanding Economic Principles - What Is Money Inflation Federal Reserve Free MarketDocument5 pagesUnderstanding Economic Principles - What Is Money Inflation Federal Reserve Free MarketphaedrisNo ratings yet

- Republics & DemocraciesDocument17 pagesRepublics & DemocraciesC. Mitchell ShawNo ratings yet

- Gmail - Booking ConfirmationDocument1 pageGmail - Booking ConfirmationB KARTHIKNo ratings yet

- Sardar Bahadur Khan Women's UniversityDocument1 pageSardar Bahadur Khan Women's UniversityMohammad Iqbal SharNo ratings yet

- Requirements For Delayed Registration of Report of BirthDocument2 pagesRequirements For Delayed Registration of Report of BirthfallingobjectNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Loss - Plan St. Peter - LPA - POLICY CARD - FERRANCULLO EMENDocument3 pagesAffidavit of Loss - Plan St. Peter - LPA - POLICY CARD - FERRANCULLO EMENMeynard MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Special Power of Attorney for Birth CertificateDocument2 pagesSpecial Power of Attorney for Birth CertificateJocel DelmonteNo ratings yet

- Pro Forma Affidavit of LossDocument1 pagePro Forma Affidavit of LossErin GamerNo ratings yet

- Requirements For PLDT RedemptionDocument3 pagesRequirements For PLDT RedemptionJulliene AbatNo ratings yet

- Aff of Discrepancy KeyesDocument1 pageAff of Discrepancy KeyesHannahQuilangNo ratings yet

- PESP 4 Advert Pretoria 06 June 2023Document5 pagesPESP 4 Advert Pretoria 06 June 2023Tania MagushanaNo ratings yet

- Aff. Daneco-Not ResidentDocument3 pagesAff. Daneco-Not Residenthudor tunnelNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of ConstitutionDocument2 pagesSalient Features of ConstitutionHrituraj SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Overturns Landmark Ruling on Amending Fundamental RightsDocument128 pagesSupreme Court Overturns Landmark Ruling on Amending Fundamental RightsR VigneshwarNo ratings yet

- The Visa RulesDocument10 pagesThe Visa RulesThe WireNo ratings yet

- BC Vital Statistics Agency - Application For Change of NameDocument4 pagesBC Vital Statistics Agency - Application For Change of Namered snflrNo ratings yet

- Request For Permission To Reproduce ImagesDocument2 pagesRequest For Permission To Reproduce ImagesRishiNo ratings yet

- Chennai Death Certificate DetailsDocument1 pageChennai Death Certificate DetailsGodwin Gabriel100% (1)

- AFFIDAVITDocument1 pageAFFIDAVITMasterErickNo ratings yet

- Capricorn Authorisation LetterDocument1 pageCapricorn Authorisation LetterVenkataraju BadanapuriNo ratings yet

- Fort - Fts - The Teacher and ¿Mommy Zarry AdaptaciónDocument90 pagesFort - Fts - The Teacher and ¿Mommy Zarry AdaptaciónEvelin PalenciaNo ratings yet

- Treasurers AffidavitDocument1 pageTreasurers AffidavitRegi PonferradaNo ratings yet

- BKD Oath of OfficeDocument13 pagesBKD Oath of OfficeGelica de JesusNo ratings yet